Abstract

Settings that that have ecological variables that instill hope might be particularly effective for treating individuals with substance use disorders. More specifically, trust and sense of community could be of importance in the fostering of hope among individuals in recovery from substance use disorders. Our study included a sample of individuals who were living in or had lived in Oxford House recovery homes. We found both sense of community and trust are ecological aspects of settings that had important influences on hope, as an engaged individual tends to value trust relationships. Perceptions of the house operating effectively was positively related to an individual’s assessment of the house as a good setting, but the house was not perceived to be as effective when the residents were not invested in the setting. The sense of community Self factor was the best predictor of hope, suggesting that an individual’s personal investment in their house community are related to their hopefulness in terms of goal attainment and opportunities. Associations of hopefulness, personal commitment, and a supportive ecology provide evidence that an individual’s perspective on recovery encompasses personal, environmental, and temporal perceptions.

Motivational issues have long been a focus of substance abuse treatment and recovery. Thus settings that maintain motivation by instilling and maintaining hope might be particularly effective for treating individuals with substance use disorders. Substance dependence is maintained by a powerful set of reinforcers, for example, attenuation of negative emotions, temporarily enhanced sense of well-being, and social connection with other users. In order for recovery to be initiated and sustained, therefore, the motivation to do so must be maintained. Recovery appears to be initiated for many different reasons, including but certainly not limited to alcohol-related problems, concern of friends and relatives, etc. This intention can be fragile, however, as negative emotions and life events, substance cues and associations and the feelings of failure associated with a relapse, among other things, can take a toll on the best of intentions (Jason, Olson, & Foli, 2008). For many in recovery, a supportive environment is a key ingredient for maintaining sobriety. Arguably, one of the primary mechanisms associated with such environments is the way they maintain and support motivation. Furthermore, it is reasonable to suppose that motivation is supported, in part, by providing the recovering individual with regular reminders of future positive outcomes—that is to say, with hope. In this article, we examine the effects of attachment to a recovery-supportive community and interpersonal trust on hope.

An important part of a recovery community is the psychological sense of community, and Jason, Stevens, and Ram (in press) have conceptualized it based on an ecological model involving three layers. At the “individual” level, people have their own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, which are ingrained within the next ecological level of “membership”, an individual’s immediate network such as family, friends, coworkers, and classmates. At the highest ecological level, these domains are embedded within a macrosystem comprising governments, cultures, and societies. Jason et al. found good measurement model fit and internal reliabilities for this 3-factor ecological model, but the participants were college students, so there is a need to replicate these findings with non-student populations.

Sense of community, in turn, is ultimately a result of interpersonal relationships, i.e., positive personal relationships such as friendships. Trust is a critical precursor of close relationships in a wide variety of settings (Horst & Coffé, 2012). Trust tends to develop in groups as members become familiar with each other over time, especially when the individuals in the group are dependent on each other for desired outcomes (Schachter, 1951). Jason, Light, Stevens, and Beers (2014) recently examined interrelationships among different levels of trust and formation of confidant relationships. Their research with individuals in recovery homes showed that high trust is increasingly likely among residents with more time in residence, and high trust is necessary to the formation of confidant relationships. These associations begin to sketch the outlines of a pathway to a successful residence experience, and that finding a confidant, or mentor may be a key pathway for continued sobriety. The contextual variable of trust might be an essential ingredient for successful recovery within these recovery homes.

Unfortunately, little research has been done on the importance of these contextual influences on individual levels of hopefulness. For example, Snyder’s (1991) two domains within the construct of hope (i.e., an individual’s affective sense of successful determination in meeting goals and an individual’s successful plans to meet goals) do not addresses the contextual opportunities, barriers, or risks an individual perceives in an appraisal of hopefulness. The influence of social networks and social support on an individual’s experience of hope has largely has been ignored.

It is very possible that addictions dismantle characteristics of resilience and hope (Jason et al., 2008), whereas trust and sense of community might help cultivate hope because of its qualities for goal setting and motivation. Community psychology provides a unique framework from which to examine contextual influences on feelings of hope. The current study utilized a sample of individuals in recovery, living in OHs. This cross-sectional exploratory investigation investigated the relationships of sense of community and trust to hope. We expected that hope would be significantly associated with an individual’s commitment or engagement in their OH community.

Method

Procedure and Participants

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire that asked questions about age, race, education, work history, and criminal history. For participating in the survey, participants were given a raffle ticket for a chance to win a new mini iPad. A total of 255 respondents were recruited at the 2014 annual Oxford House conference in Washington, DC (demographic characteristics as well as a full report on this study can be obtained by contacting the first author).

Measures

Sense of Community

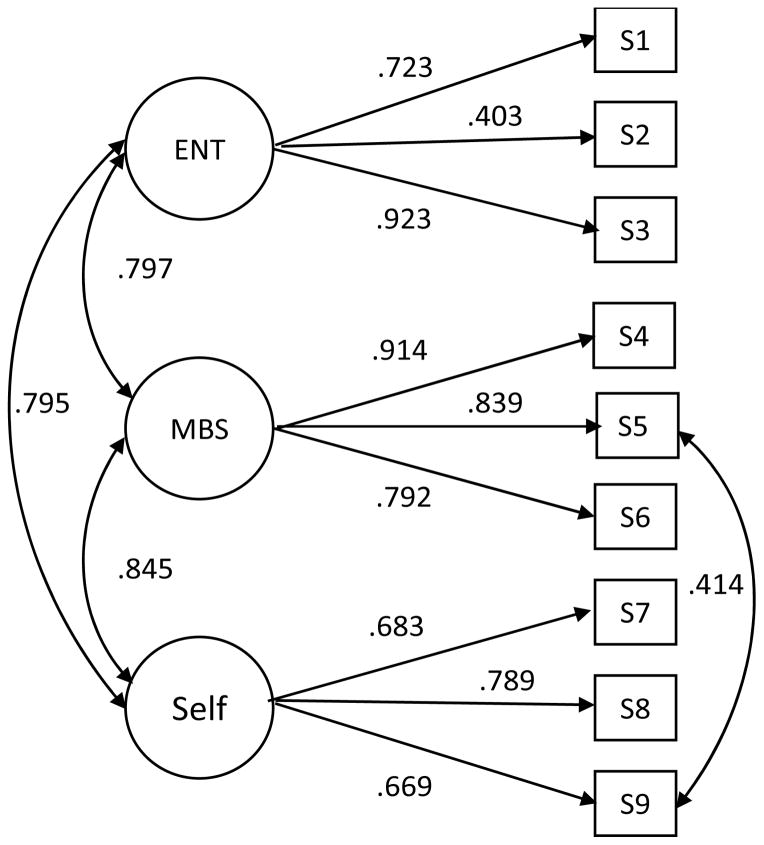

The Psychological Sense of Community Scale (PSC) consists of 9 items that tap three domains including: Entity, Membership, and Self (Jason, Stevens, & Ram, in press). The Entity (Cronbach’s α = .707) domain represents organization, purpose, and effectiveness. Items include: “I think this house is a good house” (S1), “I am not planning on leaving this house” (S2), and “For me, this house is a good fit” (S3). The Membership (Cronbach’s α = .901) domain reflects social relationships and taps the following qualities: mutual responsibility, support, cooperation, and voice. For the Membership domain, items include: “Residents can depend on each other in this house” (S4), “Residents can get help from other residents if they needed it” (S5), and “Residents are secure in sharing opinions or asking for advice” (S6). The Self (Cronbach’s α = .828) domain involves identity and importance to self, and taps concepts such as commitment, emotional connection, and meaningfulness. Items in the Self domain include: “This house is important to me” (S7) “I have friends in this house” (S8), and “I feel good helping the house and the residents” (S9).

Trust

We constructed an eight item exploratory instrument to investigate and measure Trust within the house. Based on their opinions and experiences as a current resident of an Oxford House, participants responded on a 6 point scale (ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree). Examples of items included: “When someone new comes into the house, they are trusted until they break that trust” (T3) and “Being trusted by someone makes a big difference in how I feel about myself” (T4), “Residents are rarely affected by a single individual’s behavior” (T2), “On average, a person can do really well at an Oxford House even if they don’t make any friends” (T6), and “If a person develops a reputation for being distrustful, the house just usually adapts by not giving the person important responsibilities” (T8).

State Hope Scale

Participants completed Snyder’s et al. (1996) State Hope Scale (for this sample, Cronbach’s α = .813) consisting of 6 items scored on an 8 point Likert-type scale (1 = definitely false, 8 = definitely true). For the SEM analysis, the Agency related items were utilized as Agency in previous studies has been shown to be a better predictor of hope related phenomenon (Arnau, Rosen, Finch, et al., 2007). The Agency subscale exhibited good to excellent observed reliability (Cronbach’s α = .850). The 3 Agency items were: “At the present time, I am energetically pursuing my goals” (H-A 2), “Right now I see myself as being pretty successful” (H-A 4), and “At this time, I am meeting the goals I have set for myself” (H-A 6).

Hope included a subscale to measure contextual influences on hopefulness, which had been developed by Stevens, Buchannan, Ferrari, Jason, and Ram (2014). To measure “environmental context,” three Context single-items assessed opportunities, choices, and obstacles: “Right now I don’t feel limited by the opportunities that are available (H-C 7), “I feel like I have plenty of good choices in planning my future” (H-C 8), and “The obstacles I face are similar to what everybody else faces” (H-C 9). This subscale had a Cronbach’s α equal to .729.

Results

Measurement Properties

We employed a confirmatory factor analysis for the 9 sense of community items to verify the factor structure with the OH sample found in Jason, Stevens and Ram (in press). We found a three factor structure (Entity, Membership, Self) for the Psychological Sense of Community Scale. This structure (see Figure 1) is consistent by having the same items on the same factors (i.e. configural invariant) with the scale’s prior derivation (Jason et al. in press), and the current sample exhibited good to excellent fit statistics (CFI = .983, TLI = .971, RMSEA = .063, SRMR = .032).

Figure 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the Psychological Sense of Community Scale showing three factors (ENT: entity, MBS: membership, and Self: self)

Although the trust items were not conceived as a psychometric scale but as individual items, exploratory factor analysis was performed to investigate empirically the latent structure of these data. The average correlation across items was relatively low (average ICC = .118) so combining items to simply reduce unique variance would be a problematic endeavor, but exploring possible structures seemed meaningful. The best fit was for a two factor model (CFI = .997, RMSEA = .01). The two factors were associated with House Operation and Member Trust. For further analysis, the best loading items (each which loaded at .4 or higher) per factor were utilized with SEM to eliminate the need for a series of individual item relationship tests. For House Operation, the items were “Residents are rarely affected by a single individual’s behavior” (T2), “On average, a person can do really well at an Oxford House even if they don’t make any friends” (T6), and “If a person develops a reputation for being distrustful, the house just usually adapts by not giving the person important responsibilities” (T8). For Member Trust, the items were “When someone new comes into the house, they are trusted until they break that trust” (T3) and “Being trusted by someone makes a big difference in how I feel about myself” (T4).

Relationships of Sense of Community and Trust

Our next exploratory step was to investigate the relationships between trust and sense of community; however, we did not want to add hope into this initial model because we first wanted to determine whether there were relationships between sense of community and trust. The sense of community factor Membership was not utilized in the SEM analysis described below as it provided no unique information incremental to Self and Entity in modeling. A structural regression model utilizing latent variables for sense of community and trust was tested to examine direction and strength of relationships between these constructs. The model exhibited excellent fit characteristics (χ2(df=37) = 47.06, p = .1243, CFI= .979, TLI = .968, RMSEA = .039, SRMR = .054) and had three significant paths between latent constructs. The Self component of sense of community was significantly and positively related to the Member Trust. In other words, an engaged individual tends to value trust relationships. House Operation was positively related to Entity and negatively related to Self, indicating that the perception of the house operating effectively was positively related to an individual’s assessment of the house as a good setting, but the house was not perceived to be as effective when the residents are not invested in the setting. When the individual Self places importance to this setting and relationships, these findings suggest a version of the golden rule—treat others as you would have them treat you; that is, being trusted has value and presumes trust until there is adverse evidence. These trust relationships are statistically independent, indicating that these factors are accounting for two independent aspects of an effective house.

Relationships of Trust, Sense of Community, & Hope

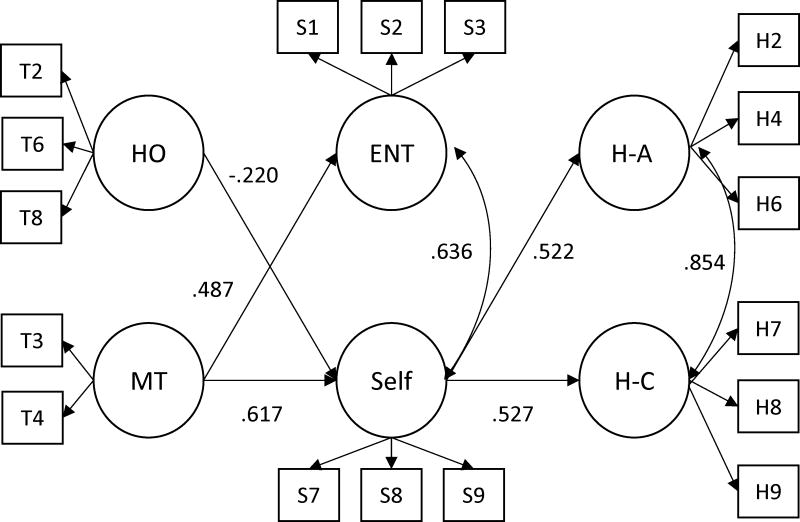

Hope was added as a latent construct to a modification of the structural regression model to investigate how sense of community was related to hopefulness. Sense of community was modeled as a result of trust relations and a predictor of hope relations. In other words, we wanted to test trust as an exogenous variable predicting sense of community, and this trust based sense of community as a predictor of hope. Hope was modeled as a two factor model consisting of Agency per the definitions of Snyder et al. (1996) and Context (Stevens et al., 2014) (see Figure 2). The model exhibited excellent fit characteristics (χ2(df=106) = 121.676, p = .1416, CFI= .986, TLI = .982, RMSEA = .028, SRMR = .051). This model indicates that as before, Member Trust was significantly related to sense of community Self, indicating that when residents value trusting relationships, they tend to be engaged as individuals. As before, Self was negatively associated with the perception that House Operation, meaning that but the house was not perceived to be as effective when the residents are not invested in the setting. Unlike the previous model, there was a significant relationship between Member Trust and Entity.

Figure 2.

Structural model of the relationships between trust, sense of community and hope

Note: For Trust: HO = House Operation, MT = Member Trust

For Sense of Community: ENT = Entity, Self = Self

For Hope: H-A = Agency, H-C = Context

In addition, there were two significant positive paths between sense of community Self and the hope variables of Agency and Context. The Self factor was the best predictor of hope, for both agency and context. This result would seem to suggest that an individual’s personal investment in their house community are related to their hopefulness in terms of goal attainment and opportunities.

Discussion

The present study examined sense of community within three ecological layers: the individual, a microsystem of membership, and a macrosystem of organization. These three ecologically and theoretically relevant domains had previously emerged with a college student sample (Jason, Stevens et al., in press). In that prior study, we had asked students to reflect on an easily accessible and remembered experience in order to understand feelings of sense of community at an individual level. Some participants chose groups from their past as their reference group and others chose current groups. As the measures were filled out with possible different time frames, and rated different groups in the Jason et al. (in press) study, our current study provided a similar timeframe and a specific reference group for ratings. Our prior findings were replicated with an OH sample, and we again found good measurement fit with factors having good internal reliabilities. This provides support for our new way of assessing and conceptualizing sense of community.

Trust develops from evidence of common recovery goals, as exemplified by similar recovery-related behaviors and attitudes, and then mediates the formation of close relationships. Our measure of trust was newly created and intended to explore different aspects of trust within the operation of an Oxford House. A number of prior efforts to measure trust have used network survey questions, such as Jason, Light, Stevens, and Beers (2014), who found that high trust is necessary to the formation of confidant relationships. The current study helps us better understand the nature and normative dispositions towards trust by OH residents which these findings would indicate that trust is important for house operation, that being trusted has personal value, and that a presumption of trust at some level is usual.

Sense of community’s relationship to these indicators of trust suggest that a strong endorsement of Entity was related to a strong endorsement of an OH operating effectively, generally independent of personal relationships. Self, or the personal priority and investment, in sense of community was positively related to Member Trust and negatively related to an OH operating effectively without personal engagement. A summary perspective might be that an OH may provide a sound framework or structure for success but that personal investment and reciprocal trust are important elements.

Our measure of hope suggests that context may be a salient resource in a person’s recovery from substance abuse. A prior study by Stevens et al. (2014) found that one’s perceived context (i.e., opportunities, choices, & obstacles) is related to one’s self-reported levels of hope. In fact, approximately 50% of an individual’s hopefulness was explained by contextual factors. The current study also found that an individual’s level of hope (as a state) was also related to context. We found that hope was significantly associated with an individual’s commitment or engagement in their OH community. This personal investment, which was positively related with member trust and negatively related to OH as simply a mechanism independent of resident relationships, was predictive of both perceptions of opportunities and barriers, and perceptions of attainment or agency. These associations of hopefulness, personal commitment, and a supportive ecology provide evidence that an individual’s perspective on recovery encompasses personal, environmental, and temporal perceptions.

In summary, settings that that have ecological variables that instill hope might be particularly effective for treating individuals with substance use disorders. Hope is at least one component of a successful recovery process. Research is now needed that would provide insight on within house structure and dynamics as predictors of an individual’s likelihood of maintaining a positive recovery trajectory, identify contributions of external recovery behaviors (e.g., AA), external ego-centered networks (scope, composition, dynamics), and within-setting social networks. Thus by identifying mechanisms through which social environments affect health outcomes and looking at system-level evolution, research could contribute to reducing health care costs by improving the effectiveness of the residential recovery home system in the US and also restructuring and improving other community-based recovery settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the financial support from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA grant numbers AA12218 and AA16973), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA grant numbers DA13231 and DA19935), and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (grant MD002748).

Contributor Information

Leonard A. Jason, DePaul University

Ed Stevens, DePaul University.

John M. Light, Oregon Research Institute

References

- Arnau R, Rosen D, Finch J, Rhudy J, Fortunato V. Longitudinal effects of hope on depression and anxiety: a latent variable analysis. Journal of Personality. 2007;75:43–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst M, Coffé H. How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research. 2012;107:509–529. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9861-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Olson BD, Foli K. Rescued lives: The Oxford House approach to substance abuse. New York: Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Light JM, Stevens EB, Beers K. Dynamic social networks in recovery homes. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;53:324–334. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9610-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jason LA, Stevens E, Ram D. Development of a three-factor psychological sense of community scale. Journal of Community Psychology. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21726. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter S. Deviation, rejection, and communication. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1951;46:190–207. doi: 10.1037/h0062326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST. The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual- differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60:570–585. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Sympson SC, Ybasco FC, Borders TF, Babyak MA, Higgins RL. Development and validation of the state hope scale. Journal of Personality nd Social Psychology. 1996;70:321–335. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens EB, Buchannan B, Ferrari JR, Jason LA, Ram D. An investigation of hope and context. Journal of Community Psychology. 2014;42:937–946. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]