A systematic literature review was conducted to identify candidate predictors of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors that could be used to develop prediction models of HRQoL deterioration. A model of HRQoL was developed based on the biopsychosocial framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, which serves as a basis for selecting candidate HRQoL predictors and thereby provides conceptual guidance for developing comprehensive, evidence-based prediction models of HRQoL for CRC survivors.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer survivors; Candidate predictors; Health-related quality of life; Systematic review; International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

Abstract

The population of colorectal cancer (CRC) survivors is growing and many survivors experience deteriorated health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in both early and late post-treatment phases. Identification of CRC survivors at risk for HRQoL deterioration can be improved by using prediction models. However, such models are currently not available for oncology practice. As a starting point for developing prediction models of HRQoL for CRC survivors, a comprehensive overview of potential candidate HRQoL predictors is necessary. Therefore, a systematic literature review was conducted to identify candidate predictors of HRQoL of CRC survivors. Original research articles on associations of biopsychosocial factors with HRQoL of CRC survivors were searched in PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar. Two independent reviewers assessed eligibility and selected articles for inclusion (N = 53). Strength of evidence for candidate HRQoL predictors was graded according to predefined methodological criteria. The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) was used to develop a biopsychosocial framework in which identified candidate HRQoL predictors were mapped across the main domains of the ICF: health condition, body structures and functions, activities, participation, and personal and environmental factors. The developed biopsychosocial ICF framework serves as a basis for selecting candidate HRQoL predictors, thereby providing conceptual guidance for developing comprehensive, evidence-based prediction models of HRQoL for CRC survivors. Such models are useful in clinical oncology practice to aid in identifying individual CRC survivors at risk for HRQoL deterioration and could also provide potential targets for a biopsychosocial intervention aimed at safeguarding the HRQoL of at-risk individuals.

Implications for Practice:

More and more people now survive a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. The quality of life of these cancer survivors is threatened by health problems persisting for years after diagnosis and treatment. Early identification of survivors at risk of experiencing low quality of life in the future is thus important for taking preventive measures. Clinical prediction models are tools that can help oncologists identify at-risk individuals. However, such models are currently not available for clinical oncology practice. This systematic review outlines candidate predictors of low quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors, providing a firm conceptual basis for developing prediction models.

Abstract

摘要

结直肠癌 (CRC) 幸存者人群正在日益增加, 许多幸存者在治疗后早期和远期发生了健康相关生活质量 (HRQoL) 恶化。使用预测模型有可能改善对有 HRQoL 恶化风险的 CRC 幸存者的鉴别。但是目前肿瘤学临床实践中还没有这类模型。对可能的备选 HRQoL 预测因素进行全面综述是开发 CRC 幸存者 HRQoL 模型所必要的第一步。因此, 我们对鉴别 CRC 幸存者的备选 HRQoL 预测因素进行了系统性文献综述。我们在 PubMed、Embase 和 Google Scholar 对与 CRC 幸存者 HRQoL 相关的生物心理社会学因素的原创研究文献进行了检索。由 2 名独立评审员对文章的合格性进行评估, 并且选择入选文献 (N=53)。根据预先定义的方法学标准对备选 HRQoL 预测因素的证据强度进行评级。使用世界卫生组织颁布的国际功能、残疾和健康分类 (ICF) 建立生物心理社会学框架, 鉴别出来的备选 HRQoL 预测因素分布在 ICF 的主要领域中: 健康状况、身体结构和功能、活动程度、参与性, 以及个人和环境因素。建立的生物心理社会学 ICF 框架可作为选择备选 HRQoL 预测因素的基础, 从而为建立 CRC 幸存者 HRQoL 的综合循证预测模型提供概念性指导。这类模型对肿瘤学临床实践十分有用, 可有助于鉴别出存在 HRQoL 恶化危险因素的 CRC 幸存者个体, 同时, 就为 HRQoL 在险个体提供保护措施而言, 该模型也能给出实施生物心理社会学干预的可能靶点。The Oncologist 2016;21:433–452

对临床实践的提示: 如今, 越来越多的确诊结直肠癌患者能够存活下来。而诊断和治疗后持续存在的健康问题年复一年地威胁着这些癌症幸存者的生活质量。因此, 在未来早期鉴别出存在生活质量降低风险的幸存者对于采取预防性措施十分重要。临床预测模型是能够帮助肿瘤科医生鉴别在险个体的工具。然而目前肿瘤学的临床实践中还没有这类模型。本项系统综述概略地给出了结直肠癌幸存者低生活质量的备选危险因素, 为建立预测模型提供了坚实的理论依据。

Introduction

Globally, the number of people surviving colorectal cancer (CRC) is growing [1, 2]. CRC and its treatment can be accompanied by adverse effects that may compromise the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of CRC survivors [3, 4]. CRC treatment can cause symptoms such as pain, bowel dysfunction, and fatigue that can negatively impact physical functioning and performance of activities of daily living [5, 6]. Additionally, a CRC diagnosis can have a strong psychological impact on emotional functioning, such as fear about the illness and death, that could lead to sleep disruption, anxiety, and depression [6, 7]. Furthermore, CRC survivors may experience restrictions in social and role functioning, particularly their ability to participate in community activities, engage in social networks, and perform work [8]. Thus, CRC survivors are frequently in need of care aimed at safeguarding their HRQoL.

Identification of CRC survivors at risk for HRQoL deterioration is crucial for providing appropriate care. Clinical prediction models of HRQoL can serve as an invaluable aid in practice to identify at-risk individuals, based on a multivariable set of HRQoL predictors [9]. These types of prognostic models estimate the probability of a future health-related outcome (e.g., HRQoL) on the basis of a multivariable combination of predictors. Such prior knowledge could help clinicians make informed decisions about tailored care in anticipation of possible future HRQoL deterioration [10]. However, no evidence-based prediction models for HRQoL of CRC survivors are currently available for clinical oncology practice. A broad overview of potential candidate predictors constitutes the first step toward developing evidence-based prediction models that incorporate relevant candidate HRQoL predictors based on the current best evidence from HRQoL studies in CRC survivors [11, 12].

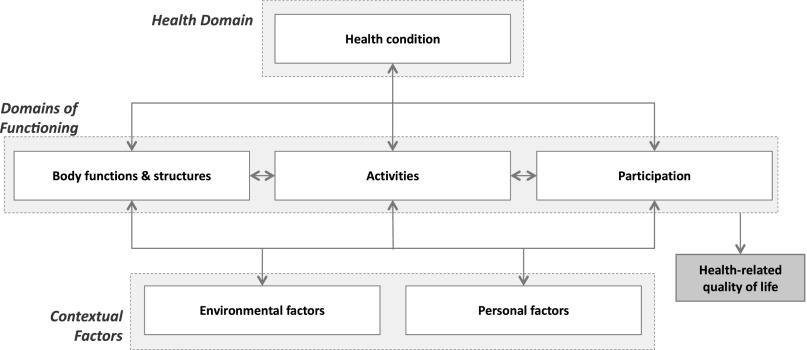

Since the concept of HRQoL is complex and multidimensional, comprising physical, social, emotional, and cognitive aspects [13], use of a guiding theoretical framework is recommended to improve the identification of potential candidate HRQoL predictors [14]. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) can be used for that purpose as a health condition-specific classification and mapping system for HRQoL research [15]. The ICF is a biopsychosocial framework of health and functioning, developed by the World Health Organization [16], in which HRQoL is conceptualized as the subjective perception of an individual’s level of functioning and health status within the context of environmental and personal factors (Fig. 1) [17, 18]. Recently, the applicability of the ICF for studying relevant aspects of HRQoL in CRC survivors was reported [19]. The ICF emphasizes both biomedical and psychosocial aspects of health and functioning, as well as contextual factors that influence functioning; therefore, the ICF framework is useful for comprehensive mapping of candidate HRQoL predictors.

Figure 1.

The biopsychosocial framework of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [16]. Health-related quality of life is conceptualized in the framework as the subjective perception of an individual’s level of functioning or disability in the context of the individual’s health condition and environmental and personal factors [17, 19].

The aim of this systematic literature review was to identify important candidate predictors of HRQoL of CRC survivors through an ICF-based biopsychosocial approach, thereby providing conceptual guidance for developing evidence-based prediction models of HRQoL of CRC survivors. Such prediction models are useful clinical aids for identifying individuals at risk for HRQoL deterioration following CRC diagnosis and treatment, and can also provide potential targets for behavioral (e.g., lifestyle) and psychosocial interventions aimed at safeguarding the HRQoL of at-risk CRC survivors.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

The main research question for the systematic review was “What are relevant biopsychosocial candidate predictors of HRQoL of CRC survivors?” For the purpose of this systematic review, a CRC survivor was defined as any individual living with a CRC diagnosis (any tumor stage) from the time of diagnosis until the end of life [20]. HRQoL was defined as the QoL related to one’s health and functioning status (i.e., the subjective perception of an individual’s level of functioning or disability in the context of the individual’s health condition and environmental and personal factors) [17, 18, 21]. A candidate predictor was defined as any biopsychosocial factor (i.e., related to demographic, clinical, psychological, lifestyle, and social characteristics) having an association with HRQoL, either cross-sectionally or longitudinally.

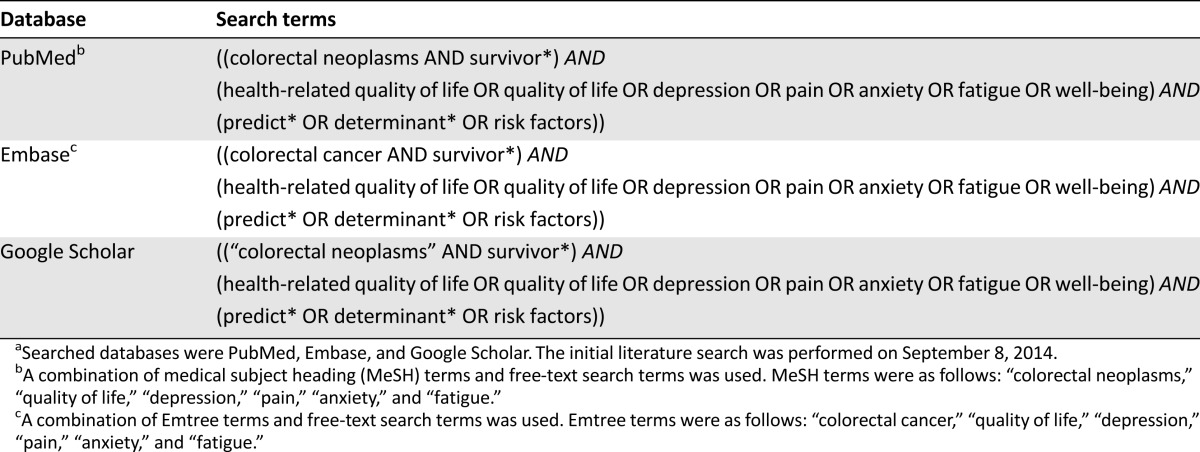

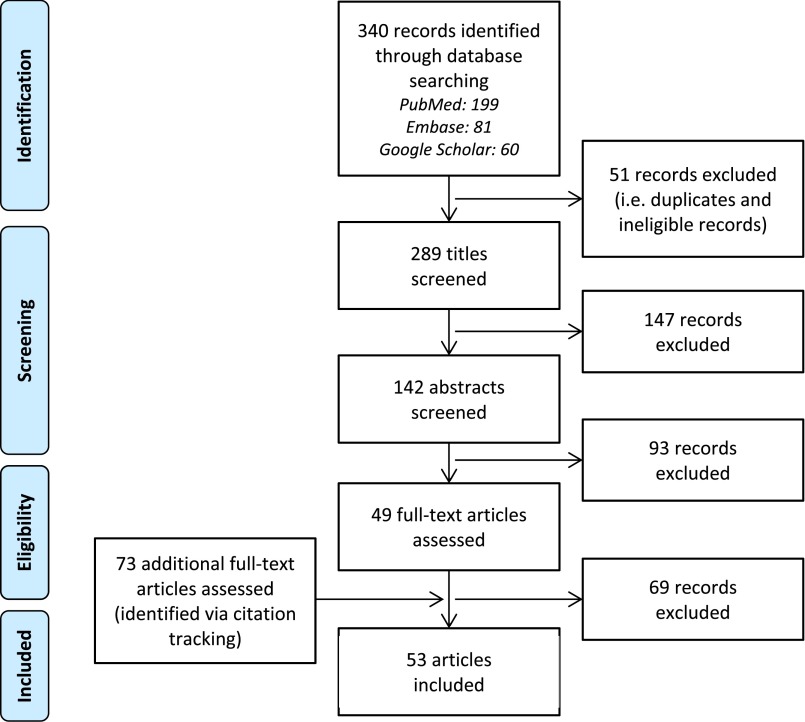

PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar were used for the systematic literature search (Table 1). Eligible for inclusion were original research articles describing results of multivariable analyses in CRC survivors, with HRQoL as primary outcome. Articles presenting results of only univariate analyses were considered not eligible because of the inherent multivariable nature of prediction models [9]. Detailed eligibility criteria are presented in Table 2. In total, 289 records were potentially eligible for inclusion (Fig. 2). The titles and abstracts of these records were systematically screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers (B.W.A.v.d.L., M.J.L.B) who reached consensus on excluding records at this stage only when those records were clearly not eligible (e.g., review articles or etiologic studies) and on the final selection of 49 records eligible for full-text screening. The two reviewers subsequently assessed eligibility of full-text articles. Through citation tracking, 73 additional records were identified and full texts of these articles were also assessed for eligibility. Finally, 53 articles were included in the review (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Search terms used for systematic literature searcha

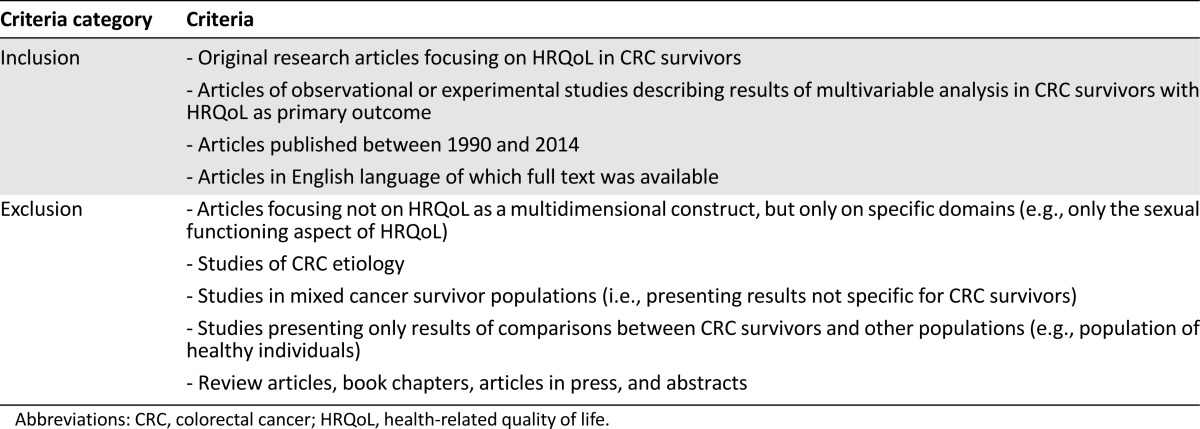

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria for selection of original research articles to be included in the review

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of record identification and screening phases, eligibility assessment, and number of included articles (according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement [94]). During screening of titles and abstracts, only records that were considered clearly ineligible by two independent reviewers were excluded for further (full-text) screening (e.g., a review article or an etiologic study).

Grading the Evidence

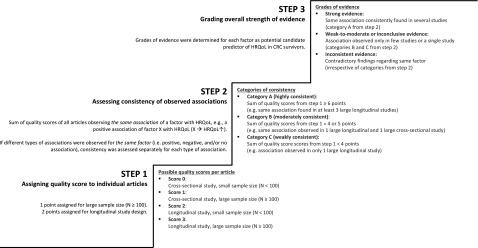

During data extraction, potentially relevant candidate HRQoL predictors were initially identified based on statistical significance (i.e., factors for which a statistically significant association with HRQoL was observed in individual studies). Next, the strength of evidence for identified factors was assessed by a straightforward, stepwise scoring and grading procedure, based on previously recommended procedures for assessing the quality of evidence from prognostic research [22, 23]. Briefly, the procedure consisted of three consecutive steps (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Stepwise scoring and grading procedure applied to assess the strength of evidence for candidate predictors of HRQoL of CRC survivors. In step 2, previously published linking rules for the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [24] were used to group factors that were conceptually alike by linking them to the corresponding ICF category. As an example, the factors psychological distress, anxiety, and depression correspond to the same ICF category: b152 Emotional functions. Articles observing similar associations of these factors with HRQoL were therefore grouped, and quality scores from step 1 for these articles could thus be summed to assess the consistency of evidence for associations of these particular factors with HRQoL.

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

First, a quality score was assigned to each individual study based on study design (longitudinal vs. cross-sectional studies) and sample size (n < 100 vs. n ≥ 100). The methodological rationale behind the quality score was that longitudinal studies provide more valid prognostic evidence than cross-sectional studies and that larger studies provide more reliable evidence than smaller studies [22]. Second, the consistency of evidence for each of the identified factors was assessed across different studies by summing the quality scores from step 1 for individual studies that observed the same association of a particular factor with HRQoL. An established ICF linking procedure was used in this step to group factors that were conceptually alike by linking them to the corresponding ICF category [24]. The consistency of evidence was categorized as follows: A = highly consistent (sum score ≥6 points), B = moderately consistent (sum score of 4–5 points), and C = weakly consistent (sum score <4 points). The third step comprised the grading of the overall strength of evidence for potential candidate HRQoL predictors. For each identified factor, the evidence was graded as “strong” if it was a factor belonging to category A from step 2; “weak-to-moderate/inconclusive” if it was a factor belonging to categories B or C from step 2; or “inconsistent” in case of contradictory findings for the same factor in different studies, irrespective of the categories assigned in step 2.

Mapping Factors Into the ICF Framework

Identified factors were mapped into the appropriate domains of the ICF framework, based on the ICF linking procedure applied during step 2 of the evidence grading. For example, body mass index (BMI) was linked to the ICF category b530 “Weight maintenance functions,” which belongs to the body structures/functions domain of the ICF framework. In this way, a conceptual biopsychosocial model of potential candidate predictors of HRQoL was developed for CRC survivors.

Results

Study Characteristics

Study populations consisted of CRC survivors (n = 42), or exclusively rectal cancer (n = 7) or colon cancer survivors (n = 4). In total, 36 studies were cross-sectional and 17 were longitudinal. The most frequently used cancer-specific HRQoL questionnaires were the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (N = 19) [25] and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ)-Core 30 (N = 12) [26], often supplemented with the CRC-specific module EORTC QLQ-CR38 (N = 8) [27]. The Short-Form Health Survey was the most frequently used generic HRQoL questionnaire (N = 18) [28]. The included articles (N = 53) were published between 1994 and 2014 (Table 3).

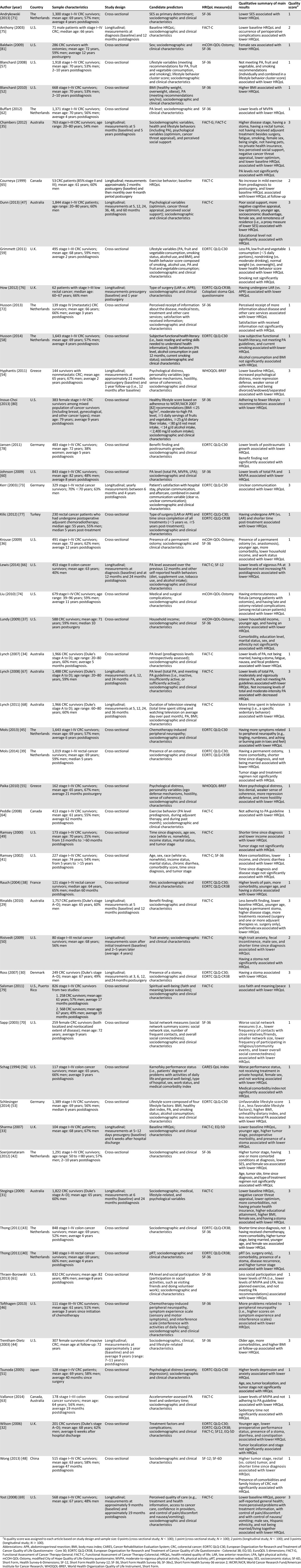

Table 3.

Overview of articles included in the systematic review (N = 53)

Strength of Evidence for Potential Candidate Predictors Within ICF Domains

The identified factors were mapped into the biopsychosocial ICF framework and arranged in accordance with the graded strength of evidence for their potential relevance as candidate HRQoL predictors (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Candidate predictors of low HRQoL of colorectal cancer survivors, mapped into the biopsychosocial framework of the ICF. Candidate HRQoL predictors are arranged in the framework according to the graded strength of evidence (i.e., strong evidence, weak-to-moderate or inconclusive evidence, and inconsistent evidence).

Abbreviations: APR, abdominoperineal resection; BMI, body mass index; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; ICF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; LAR, low anterior resection; SES, socioeconomic status.

ICF Domains

Health Condition

Evidence was graded strong for the presence of a stoma and comorbidity. Twelve studies (5 longitudinal) consistently demonstrated that CRC survivors with a stoma reported lower HRQoL, both in early phases from 6 weeks up to 2 years postdiagnosis [29–34] and in later phases from 2 years to over 5 years postdiagnosis [35–40]. Additionally, 9 studies (2 longitudinal) showed that CRC survivors with 1 or more comorbid conditions reported lower HRQoL up to 10 years postdiagnosis [31, 36, 38–44].

Evidence was graded weak-to-moderate/inconclusive for chemotherapy-induced neuropathy symptoms and disease recurrence. Cross-sectional associations were observed of more peripheral neuropathy symptoms in CRC survivors [45, 46] and tumor recurrence in rectal cancer survivors [40] with lower HRQoL. Evidence was graded inconsistent for tumor stage and localization. Either associations of higher tumor stage with lower HRQoL were observed [29, 33, 35, 40, 42, 43, 47, 48] or there was no significant association between tumor stage and HRQoL [32, 39, 41, 49–51]. Similarly, studies observed either no significant association between tumor localization and HRQoL [29, 32, 42, 51] or that rectal cancer survivors reported lower HRQoL than colon cancer survivors [35, 48].

Body Functions/Structures

Evidence was graded strong for BMI, fatigue, psychological distress, anxiety, and depression. Four studies (2 longitudinal) found that CRC survivors with higher BMI (i.e., >25–30 kg/m2) reported lower HRQoL in periods from 6 months up to 10 years postdiagnosis than survivors with lower BMI [31, 44, 52, 53]. Additionally, 2 longitudinal studies observed that higher levels of fatigue were associated with lower HRQoL reported by CRC survivors up to 5 years postdiagnosis [34, 35]. Four studies (2 longitudinal) found that CRC survivors with higher levels of psychological distress, anxiety, or depression reported lower HRQoL up to 5 years post-treatment [50, 51, 54, 55].

Evidence was graded weak-to-moderate/inconclusive for performance status, fecal control problems or incontinence, nausea, chronic diarrhea, constipation, pain, and smoking. Studies observed that poor performance status (i.e., problems with daily functioning) was associated with lower HRQoL reported by CRC [32] and colon cancer survivors [56]. Other studies observed associations of problems with fecal control or incontinence [34, 50], chronic diarrhea [32, 41], constipation [32], nausea [34], pain [38], and smoking [35, 57, 58] with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors.

Activities

Evidence was graded strong for physical activity. Ten cross-sectional studies showed that lower levels of total physical activity, light physical activity, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), as well as not adhering to physical activity guidelines (i.e., MVPA ≥150 minutes/week) were significantly associated with lower HRQoL in CRC survivors up to 10 years postdiagnosis [34, 53, 57–64]. Furthermore, 3 longitudinal studies found that CRC survivors who reported no change or a decrease of their habitual physical activity level postdiagnosis had lower HRQoL than survivors reporting to have increased their physical activity level up to 2 years postdiagnosis [65–67].

Ten cross-sectional studies showed that lower levels of total physical activity, light physical activity and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), as well as not adhering to physical activity guidelines (i.e., MVPA ≥150 minutes/week) were significantly associated with lower HRQoL in CRC survivors up to 10 years postdiagnosis.

Evidence was graded weak-to-moderate/inconclusive for factors related to sedentary behavior and health literacy. Associations were observed of increased television viewing time (a specific sedentary behavior) with decreased HRQoL [68]. Low subjective functional health literacy (i.e., basic reading/writing skills needed to understand health information) was associated with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors [58].

Participation

In the participation domain of the ICF, no factors were identified for which evidence was graded strong. Evidence was graded weak-to-moderate/inconclusive for participation in social activities, with only one study observing that less participation in social activities (e.g., visiting family/friends) was associated with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors [61].

Evidence was graded inconsistent for education level, work status, and marital status. One study observed associations of lower educational attainment with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors [31], whereas nine other studies did not observe an association between education level and HRQoL [29, 34, 35, 37, 47, 48, 50, 54, 55]. Additionally, either working [56] or not working [36] was observed to be associated with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors, or no significant association between HRQoL and work status was observed [48]. Several studies observed either that not being married or being divorced, widowed, or separated was associated with lower HRQoL in CRC survivors [29, 34, 39, 43, 54, 69] or found no significant association between marital status and HRQoL [35, 37, 48].

Environmental Factors

Evidence was graded strong for perceived social support; for factors related to socioeconomic characteristics, including health insurance, household income, and socioeconomic status (SES); and for factors related to perceived quality of care. In 3 studies (2 longitudinal), less perceived social support and worse social network measures (e.g., fewer social contacts) were found to be associated with lower HRQoL reported by CRC survivors 5 or more years postdiagnosis [35, 47, 70]. Regarding socioeconomic factors, 2 longitudinal studies in CRC survivors observed significantly lower HRQoL 2–5 years postdiagnosis among survivors who did not have private health insurance at 5–6 months postdiagnosis [31, 35]. Furthermore, 7 studies (1 longitudinal) found that lower household income or lower SES were associated with lower HRQoL reported by CRC survivors between 5 months and 10 years postdiagnosis [36, 37, 41, 42, 47, 49, 71]. Finally, 3 studies (2 longitudinal) observed that perceiving more problems with provision of information by care providers (e.g., about the diagnosis, illness, treatments, complications, and care services) was associated with lower HRQoL reported by both CRC survivors and rectal cancer survivors 2–4 years postdiagnosis [69, 72, 73].

Evidence was graded weak-to-moderate/inconclusive for late medical complications, short-term surgical complications, factors related to dietary habits, having received treatment in a private hospital, and having pets. In rectal cancer survivors with ostomies, ostomy-related late medical complications (e.g., fistula or urinary retention) were observed to be associated with lower HRQoL [74]. Additionally, studies observed associations of short-term surgical complications and perioperative morbidity (e.g., wound infections) with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors [33, 75]. Studies also observed that CRC survivors reporting unhealthy dietary habits (i.e., low consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole-grain bread; and high consumption of red and processed meat) reported lower HRQoL than survivors reporting healthy habits [53, 57, 59]. Furthermore, one study observed that CRC survivors who did not drink alcohol reported lower HRQoL than moderate alcohol drinkers [59]. Finally, not having received treatment in a private hospital [56] and not having pets [35] were observed to be associated with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors.

Evidence was graded inconsistent for factors related to cancer treatment. Contrasting results were found regarding the association of different types of surgery with HRQoL in rectal cancer survivors [76, 77]. Additionally, studies in CRC survivors observed either no significant association of treatment-related variables with HRQoL [34, 36, 39, 42] or that not having received adjuvant therapy besides surgery was associated with lower HRQoL [35, 43]. In contrast, other studies observed that having received adjuvant therapy (vs. surgery only) [29] or preoperative radiotherapy [40] was associated with lower HRQoL in CRC and rectal cancer survivors, respectively.

Personal Factors

Evidence was graded strong for personality factors. In 8 studies (5 longitudinal), a number of psychological variables related to the personality of CRC survivors were shown to be associated with lower HRQoL up to 5 years postdiagnosis, including lower optimism and negative cancer-threat appraisal [31, 35, 47], a weaker sense of coherence [54, 55], more repression defense [54, 55], less benefit finding [29, 78], lower posttraumatic growth [78], less faith and meaning/peace [79], and less denial and more hostility [55].

Evidence was graded weak-to-moderate/inconclusive for factors related to ethnicity and personal lifestyle behavior. In a study from the U.S., a signification association was observed between Hispanic ethnicity and low HRQoL in CRC survivors [69]. Regarding lifestyle-related factors, studies have observed that CRC survivors reported lower HRQoL when meeting fewer healthy lifestyle recommendations [53, 57, 59, 80].

Evidence was graded inconsistent for sex and age. Several studies observed that either female CRC survivors reported lower HRQoL [29, 31, 42, 43, 47, 48, 56, 81] or that male survivors reported lower HRQoL [35, 50, 69]. Other studies, however, did not observe a significant association between sex and HRQoL [34, 37, 51]. Younger age was observed to be associated with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors [29, 32, 33, 36–38, 43, 47, 48], or no significant association between age and HRQoL was observed [35, 42, 50, 51, 54, 55]; a single study among female CRC survivors observed that older age was associated with lower HRQoL [44].

Factors Not Covered or Defined in ICF

Some potentially relevant candidate HRQoL predictors identified from the included articles could not be linked to an appropriate ICF category because the meaningful concept represented by these factors was either too broad to be defined by a single, specific ICF category or domain, or was not covered by any category in the ICF. These factors, therefore, could not be mapped into the ICF framework and are depicted separately in Figure 4.

Evidence was graded strong for baseline HRQoL and time since diagnosis, and weak-to-moderate/inconclusive for self-reported general health. In 8 longitudinal studies, it was shown that lower HRQoL reported by CRC survivors at an earlier time point during the study (i.e., baseline) was associated with lower HRQoL reported at later time points during study follow-up from 6 weeks post-treatment up to 5 years postdiagnosis [29, 31, 33, 35, 54, 65, 69, 75]. Furthermore, six studies (one longitudinal) showed that shorter time since diagnosis was associated with lower HRQoL reported by CRC survivors [39, 43, 48–50, 77]. Finally, poorer self-reported general health was observed to be associated with lower HRQoL of CRC survivors [69].

Discussion

This systematic literature review presents a qualitative overview of the current state of evidence for candidate predictors of HRQoL of CRC survivors, using a novel, ICF-based approach. A conceptual biopsychosocial HRQoL model was developed providing a comprehensive overview of potentially relevant candidate HRQoL predictors according to their level of evidence (Fig. 4). This framework may serve as an evidence base for selecting relevant candidate predictors when planning to develop a prediction model of HRQoL for identifying CRC survivors at risk of HRQoL deterioration. Evidence regarding candidate predictors of low HRQoL was found to be strongest for the presence of a stoma and comorbidity (ICF domain: health condition); for high BMI and high levels of fatigue and psychological distress, anxiety, and depression (body functions/structures); for low levels of physical activity (activities); for low perceived social support, for factors related to low SES, and for low perceived quality of care (environmental factors); for several personality factors including low optimism and negative cancer threat appraisal (personal factors); and for low baseline HRQoL and shorter time since diagnosis (factors not covered or defined in ICF).

Predictors related to modifiable behaviors or characteristics of CRC survivors may provide targets for tailored interventions to prevent HRQoL deterioration in at-risk individuals. As factors related to modifiable lifestyle behavior, physical activity and BMI emerged as the most relevant candidate HRQoL predictors. Because physical activity and BMI are related to dietary habits of CRC survivors and other lifestyle behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption [83], personal lifestyle behaviors of CRC survivors should preferably be regarded in combination for prediction of their HRQoL. Indeed, CRC survivors adhering to multiple healthy lifestyle behaviors were found to report better HRQoL than survivors adhering to less healthy behaviors [53, 57, 59, 80], and beneficial effects of multibehavior lifestyle interventions on CRC survivors’ HRQoL have been shown [84–86]. In addition, several potentially modifiable psychological factors related to individual coping skills of CRC survivors were identified as relevant candidate HRQoL predictors. By influencing stress responses and ego defense mechanisms following major life events, such as a cancer diagnosis, these factors can contribute to the development of psychosomatic symptoms (e.g., fatigue, anxiety and depression) [87–89]. Interventions focusing on coping skills of CRC survivors in response to significant health stressors (e.g., cancer diagnosis/treatment, presence of a stoma or multimorbidity) may be a promising strategy to safeguard at-risk individuals against HRQoL deterioration [90].

Because physical activity and BMI are related to dietary habits of CRC survivors and other lifestyle behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption [83], personal lifestyle behaviors of CRC survivors should preferably be regarded in combination for prediction of their HRQoL.

Evidence was found to be inconsistent for tumor- and treatment-related factors, education level, work, marital status, sex, and age. Several reasons could be put forward for these inconsistent findings. First, it could be that the factor of interest is not a true predictor of CRC survivors’ HRQoL. This might be the case for education level, for which no significant association with HRQoL was observed in the majority of studies. Second, it could also be that the factor of interest may be an effect modifier (e.g., sex and age [36]), for which prediction models should be stratified. Third, inconsistent findings may be attributable to heterogeneity of CRC survivor populations across studies. For instance, studies conducted at different times postdiagnosis could have affected observed associations of certain factors with HRQoL, such as tumor stage and type of treatment, which might be more relevant for predicting HRQoL in the short term, while becoming less important over time. This would suggest that prediction models need to be developed according to time since diagnosis—that is, separate models for estimating short-term versus longer-term HRQoL. Finally, between-study differences in measurement methods (e.g., of work or marital status) may have produced inconsistent findings regarding factors representing similar concepts.

Of note, weak-to-moderate or inconclusive evidence was found for a variety of factors in every ICF domain. Although several of these factors might be very relevant for HRQoL prediction in CRC survivors (e.g., chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, sedentary behavior, and dietary habits), they had only been examined in a single or few studies that mostly had a cross-sectional design. Strikingly, no factors within the participation domain of the ICF were identified as potentially relevant candidate HRQoL predictors, for which evidence could be graded strong. As the societal aspect of functioning, the level of participation of CRC survivors presumably is relevant for their HRQoL. More research on these factors is thus warranted, preferably through prospective studies.

A major strength of this systematic review was the use of the ICF framework as guiding conceptual model of HRQoL, constituting a novel approach that has resulted in a comprehensive overview of biopsychosocial candidate HRQoL predictors for CRC survivors (Fig. 4). Our model not only encompasses biomedical and somatic aspects of health and functioning (e.g., medical conditions and disease symptoms) but also psychosocial aspects (e.g., ability to perform activities and participate in social life) and environmental and personal factors that are likely to be relevant for predicting HRQoL. Previous systematic reviews focused only on a specific subpopulation of CRC survivors [3] or on a specific class of predictors [89, 91]. As a potential limitation, we cannot exclude the possibility of publication bias. Potentially relevant articles may have been missed in our literature search, which might have been too specific. Furthermore, because there currently is a paucity of studies on prediction of HRQoL in CRC survivors, we had to rely on association studies for identification of potential candidate HRQoL predictors.

Conclusion

The results of this systematic review provide conceptual guidance for developing evidence-based prediction models for HRQoL of CRC survivors, which currently are not available. A crucial first step in prediction model development is a priori identification and evidence-based selection of relevant candidate predictors [11, 92, 93]. For that purpose, our ICF-based biopsychosocial conceptual model (Fig. 4) can be used to select candidate HRQoL predictors. Depending on available data for model development, we recommend including candidate predictors for which strong evidence was provided. Additionally, based on relevant subject matter knowledge, it is to be recommended to also consider factors for which evidence was found to be inconsistent, in order to assess their added value or potential role as effect modifiers (e.g., sex-specific models). Finally, depending on specific study circumstances and intended use of the prediction model, development of separate models (e.g., for different time periods after diagnosis or treatment) may be considered, as may selection of additional candidate predictors for which evidence was graded weak-to-moderate/inconclusive.

Importantly, the process of developing useful prediction models includes more than evidence-based selection of candidate predictors and statistical development of multivariable models. It must always include an internal validation step to optimize model performance by adjusting for overfitting (preferably using bootstrapping methods), and an external validation step to assess model performance in other, similar populations than the population used for model development (i.e., model transferability/generalizability). Finally, the usefulness of a validated prediction model also needs to be evaluated in impact studies to assess whether applying the model improves patient outcomes. Evidence-based prediction models can be used in clinical oncology practice to identify individuals at risk for future HRQoL deterioration and to provide potential targets for behavioral and psychosocial interventions that may ultimately enable better tailoring of individualized care aimed at safeguarding the HRQoL of CRC survivors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. L.V. van de Poll-Franse, professor of Cancer Epidemiology and Survivorship at Tilburg University and the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organization, for her valuable contribution to our national consortium on colorectal cancer survivorship, lifestyle, and health-related quality of life. This work was supported by a grant from the Alpe d’HuZes Foundation within the research program “Leven met kanker” of the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant UM-2012-5653) and by a VENI grant awarded to F.M. (451-10-041) from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. M.J.L.B. is financially supported by the aforementioned grant and also partly by Grant 00005739 from Kankeronderzoekfonds Limburg as part of Health Foundation Limburg. E.H.v.R. is financially supported by a grant from the Alpe d’HuZes Foundation within the research program “Leven met kanker” of the Dutch Cancer Society (Grant UM-2010-4867) and also by the GROW – School for Oncology and Developmental Biology of Maastricht University.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Martijn J.L. Bours, Bernadette W.A. van der Linden, Renate M. Winkels, Fränzel J. van Duijnhoven, Floortje Mols, Eline H. van Roekel, Ellen Kampman, Sandra Beijer, Matty P. Weijenberg

Provision of study material or patients: Martijn J.L. Bours, Bernadette W.A. van der Linden

Collection and/or assembly of data: Martijn J.L. Bours, Bernadette W.A. van der Linden

Data analysis and interpretation: Martijn J.L. Bours, Bernadette W.A. van der Linden, Matty P. Weijenberg

Manuscript writing: Martijn J.L. Bours, Bernadette W.A. van der Linden, Renate M. Winkels, Fränzel J. van Duijnhoven, Floortje Mols, Eline H. van Roekel, Ellen Kampman, Sandra Beijer, Matty P. Weijenberg

Final approval of manuscript: Martijn J.L. Bours, Bernadette W.A. van der Linden, Renate M. Winkels, Fränzel J. van Duijnhoven, Floortje Mols, Eline H. van Roekel, Ellen Kampman, Sandra Beijer, Matty P. Weijenberg

Disclosures

Martijn J.L. Bours: Alpe d'HuZes Foundation, Kankeronderzoekfonds Limburg (RF). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, et al. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1133–1145. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansen L, Koch L, Brenner H, et al. Quality of life among long-term (≥5 years) colorectal cancer survivors--systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2879–2888. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marventano S, Forjaz M, Grosso G, et al. Health related quality of life in colorectal cancer patients: State of the art. BMC Surg. 2013;13(suppl 2):S15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi Q, Smith TG, Michonski JD, et al. Symptom burden in cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: A report from the American Cancer Society’s Studies of Cancer Survivors. Cancer. 2011;117:2779–2790. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu HS, Harden JK. Symptom burden and quality of life in survivorship: A review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38:E29–E54. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, et al. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15:306–320. doi: 10.1002/pon.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deimling GT, Sterns S, Bowman KF, et al. Functioning and activity participation restrictions among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:106–116. doi: 10.1080/07357900701224813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hendriksen JM, Geersing GJ, Moons KG, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic prediction models. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(suppl 1):129–141. doi: 10.1111/jth.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hingorani AD, Windt DA, Riley RD, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 4: Stratified medicine research. BMJ. 2013;346:e5793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:W1-73. doi: 10.7326/M14-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riley RD, Hayden JA, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 2: Prognostic factor research. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barofsky I. Can quality or quality-of-life be defined? Qual Life Res. 2012;21:625–631. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9961-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costa DS, King MT. Conceptual, classification or causal: Models of health status and health-related quality of life. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;13:631–640. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2013.838024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, et al. Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:134. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. 2001: Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cieza A, Bickenbach J, Chatterji S. The ICF as a conceptual platform to specify and discuss health and health-related concepts. Gesundheitswesen. 2008;70:e47–e56. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1080933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cieza A, Stucki G. The International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health: Its development process and content validity. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008;44:303–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Roekel EH, Bours MJ, de Brouwer CP, et al. The applicability of the international classification of functioning, disability, and health to study lifestyle and quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1394–1405. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell MK, Mayer D, Abernethy A, et al. Cancer survivorship. N C Med J. 2008;69:322–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE., Jr Conceptualization and measurement of health-related quality of life: Comments on an evolving field. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(Suppl 2):S43–S51. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huguet A, Hayden JA, Stinson J, et al. Judging the quality of evidence in reviews of prognostic factor research: Adapting the GRADE framework. Syst Rev. 2013;2:71. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, et al. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:280–286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-4-201302190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cieza A, Geyh S, Chatterji S, et al. ICF linking rules: An update based on lessons learned. J Rehabil Med. 2005;37:212–218. doi: 10.1080/16501970510040263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward WL, Hahn EA, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:181–195. doi: 10.1023/a:1008821826499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Aaronson NK. The construction and testing of the EORTC colorectal cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire module (QLQ-CR38) Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:238–247. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rinaldis M, Pakenham KI, Lynch BM. Relationships between quality of life and finding benefits in a diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Br J Psychol. 2010;101:259–275. doi: 10.1348/000712609X448676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross L, Abild-Nielsen AG, Thomsen BL, et al. Quality of life of Danish colorectal cancer patients with and without a stoma. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:505–513. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steginga SK, Lynch BM, Hawkes A, et al. Antecedents of domain-specific quality of life after colorectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:216–220. doi: 10.1002/pon.1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson TR, Alexander DJ, Kind P. Measurement of health-related quality of life in the early follow-up of colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1692–1702. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0709-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma A, Sharp DM, Walker LG, et al. Predictors of early postoperative quality of life after elective resection for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3435–3442. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9554-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lynch BM, Cerin E, Owen N, et al. Associations of leisure-time physical activity with quality of life in a large, population-based sample of colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18:735–742. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chambers SK, Meng X, Youl P, et al. A five-year prospective study of quality of life after colorectal cancer. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1551–1564. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krouse RS, Herrinton LJ, Grant M, et al. Health-related quality of life among long-term rectal cancer survivors with an ostomy: Manifestations by sex. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4664–4670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lundy JJ, Coons SJ, Wendel C, et al. Exploring household income as a predictor of psychological well-being among long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:157–161. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9432-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rauch P, Miny J, Conroy T, et al. Quality of life among disease-free survivors of rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:354–360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mols F, Lemmens V, Bosscha K, et al. Living with the physical and mental consequences of an ostomy: A study among 1-10-year rectal cancer survivors from the population-based PROFILES registry. Psychooncology. 2014;23:998–1004. doi: 10.1002/pon.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thong MS, Mols F, Lemmens VE, et al. Impact of preoperative radiotherapy on general and disease-specific health status of rectal cancer survivors: A population-based study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:e49–e58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramsey SD, Berry K, Moinpour C, et al. Quality of life in long term survivors of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1228–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soerjomataram I, Thong MS, Ezzati M, et al. Most colorectal cancer survivors live a large proportion of their remaining life in good health. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1421–1428. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thong MS, Mols F, Lemmens VE, et al. Impact of chemotherapy on health status and symptom burden of colon cancer survivors: A population-based study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1798–1807. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trentham-Dietz A, Remington PL, Moinpour CM, et al. Health-related quality of life in female long-term colorectal cancer survivors. The Oncologist. 2003;8:342–349. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-4-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mols F, Beijers T, Lemmens V, et al. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and its association with quality of life among 2- to 11-year colorectal cancer survivors: Results from the population-based PROFILES registry. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2699–2707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tofthagen C, Donovan KA, Morgan MA, et al. Oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy’s effects on health-related quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:3307–3313. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1905-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dunn J, Ng SK, Breitbart W, et al. Health-related quality of life and life satisfaction in colorectal cancer survivors: Trajectories of adjustment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong CK, Lam CL, Poon JT, et al. Clinical correlates of health preference and generic health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal neoplasms. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramsey SD, Andersen MR, Etzioni R, et al. Quality of life in survivors of colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:1294–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ristvedt SL, Trinkaus KM. Trait anxiety as an independent predictor of poor health-related quality of life and post-traumatic stress symptoms in rectal cancer. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:701–715. doi: 10.1348/135910708X400462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Hiratsuka K, et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s10147-005-0524-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blanchard CM, Stein K, Courneya KS. Body mass index, physical activity, and health-related quality of life in cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:665–671. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181bdc685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlesinger S, Walter J, Hampe J, et al. Lifestyle factors and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0313-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hyphantis T, Paika V, Almyroudi A, et al. Personality variables as predictors of early non-metastatic colorectal cancer patients’ psychological distress and health-related quality of life: a one-year prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Paika V, Almyroudi A, Tomenson B, et al. Personality variables are associated with colorectal cancer patients’ quality of life independent of psychological distress and disease severity. Psychooncology. 2010;19:273–282. doi: 10.1002/pon.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schag CA, Ganz PA, Wing DS, et al. Quality of life in adult survivors of lung, colon and prostate cancer. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:127–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00435256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: Results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Husson O, Mols F, Fransen MP, et al. Low subjective health literacy is associated with adverse health behaviors and worse health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors: results from the profiles registry. Psychooncology. 2014; 24:478–486. doi: 10.1002/pon.3678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grimmett C, Bridgewater J, Steptoe A, et al. Lifestyle and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1237–1245. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9855-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Koltyn KF, et al. Physical activity and function in older, long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:775–784. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9292-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thraen-Borowski KM, Trentham-Dietz A, Edwards DF, et al. Dose-response relationships between physical activity, social participation, and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:369–378. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0277-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buffart LM, Thong MS, Schep G, et al. Self-reported physical activity: Its correlates and relationship with health-related quality of life in a large cohort of colorectal cancer survivors. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vallance JK, Boyle T, Courneya KS, et al. Associations of objectively assessed physical activity and sedentary time with health-related quality of life among colon cancer survivors. Cancer. 2014;120:2919–2926. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peddle CJ, Au HJ, Courneya KS. Associations between exercise, quality of life, and fatigue in colorectal cancer survivors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1242–1248. doi: 10.1007/s10350-008-9324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Arthur K, et al. Physical exercise and quality of life in postsurgical colorectal cancer patients. Psychol Health Med. 1999;4:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis C, Xun P, He K. Physical activity in relation to quality of life in newly diagnosed colon cancer patients: A 24-month follow-up. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2235–2246. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0679-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lynch BM, Cerin E, Owen N, et al. Prospective relationships of physical activity with quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4480–4487. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lynch BM, Cerin E, Owen N, et al. Television viewing time of colorectal cancer survivors is associated prospectively with quality of life. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:1111–1120. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9786-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yost KJ, Hahn EA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:66. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sapp AL, Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, et al. Social networks and quality of life among female long-term colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer. 2003;98:1749–1758. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Andrykowski MA, Aarts MJ, van de Poll-Franse LV, et al. Low socioeconomic status and mental health outcomes in colorectal cancer survivors: Disadvantage? advantage?... or both? Psychooncology. 2013;22:2462–2469. doi: 10.1002/pon.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Husson O, Thong MS, Mols F, et al. Information provision and patient reported outcomes in patients with metastasized colorectal cancer: Results from the PROFILES registry. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:281–288. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kerr J, Engel J, Schlesinger-Raab A, et al. Doctor-patient communication: Results of a four-year prospective study in rectal cancer patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1038–1046. doi: 10.1097/01.DCR.0000074690.73575.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu L, Herrinton LJ, Hornbrook MC, et al. Early and late complications among long-term colorectal cancer survivors with ostomy or anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:200–212. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181bdc408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anthony T, Long J, Hynan LS, et al. Surgical complications exert a lasting effect on disease-specific health-related quality of life for patients with colorectal cancer. Surgery. 2003;134:119–125. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.How P, Stelzner S, Branagan G, et al. Comparative quality of life in patients following abdominoperineal excision and low anterior resection for low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:400–406. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182444fd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kilic D, Yalman D, Aksu G, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer on the long-term quality of life and late side effects: A multicentric clinical evaluation by the Turkish Oncology Group. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5741–5746. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.11.5741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jansen L, Hoffmeister M, Chang-Claude J, et al. Benefit finding and post-traumatic growth in long-term colorectal cancer survivors: Prevalence, determinants, and associations with quality of life. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1158–1165. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Salsman JM, Yost KJ, West DW, et al. Spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life in colorectal cancer: A multi-site examination of the role of personal meaning. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:757–764. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Inoue-Choi M, Lazovich D, Prizment AE, et al. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research recommendations for cancer prevention is associated with better health-related quality of life among elderly female cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1758–1766. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baldwin CM, Grant M, Wendel C, et al. Gender differences in sleep disruption and fatigue on quality of life among persons with ostomies. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:335–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: American Institute for Cancer Research, 2007.

- 83.Ligibel J. Lifestyle factors in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3697–3704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:1883–1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Demark-Wahnefried W, Morey MC, Sloane R, et al. Reach out to enhance wellness home-based diet-exercise intervention promotes reproducible and sustainable long-term improvements in health behaviors, body weight, and physical functioning in older, overweight/obese cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2354–2361. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hawkes AL, Pakenham KI, Chambers SK, et al. Effects of a multiple health behavior change intervention for colorectal cancer survivors on psychosocial outcomes and quality of life: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2014;48:359–370. doi: 10.1007/s12160-014-9610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dunn J, Ng SK, Holland J, et al. Trajectories of psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:1759–1765. doi: 10.1002/pon.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim J, Han JY, Shaw B, et al. The roles of social support and coping strategies in predicting breast cancer patients’ emotional well-being: Testing mediation and moderation models. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:543–552. doi: 10.1177/1359105309355338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sales PM, Carvalho AF, McIntyre RS, et al. Psychosocial predictors of health outcomes in colorectal cancer: A comprehensive review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:800–809. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lambert SD, Girgis A, McElduff P, et al. A parallel-group, randomised controlled trial of a multimedia, self-directed, coping skills training intervention for patients with cancer and their partners: Design and rationale. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003337. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sharma A, Walker AA, Sharp DM, et al. Psychosocial factors and quality of life in colorectal cancer. Surgeon. 2007;5:344–354. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(07)80087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Moons KG, Kengne AP, Woodward M, et al. Risk prediction models: I. Development, internal validation, and assessing the incremental value of a new (bio)marker. Heart. 2012;98:683–690. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, van der Windt DA, et al. Prognosis Research Strategy (PROGRESS) 3: Prognostic model research. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]