Abstract

There is little agreement about what constitutes good death or successful dying. The authors conducted a literature search for published, English-language, peer-reviewed reports of qualitative and quantitative studies that provided a definition of a good death. Stakeholders in these articles included patients, prebereaved and bereaved family members, and healthcare providers (HCPs). Definitions found were categorized into core themes and subthemes, and the frequency of each theme was determined by stakeholder (patients, family, HCPs) perspectives. Thirty-six studies met eligibility criteria, with 50% of patient perspective articles including individuals over age 60 years. We identified 11 core themes of good death: preferences for a specific dying process, pain-free status, religiosity/spiritualty, emotional well-being, life completion, treatment preferences, dignity, family, quality of life, relationship with HCP, and other. The top three themes across all stakeholder groups were preferences for dying process (94% of reports), pain-free status (81%), and emotional well-being (64%). However, some discrepancies among the respondent groups were noted in the core themes: Family perspectives included life completion (80%), quality of life (70%), dignity (70%), and presence of family (70%) more frequently than did patient perspectives regarding those items (35%–55% each). In contrast, religiosity/spirituality was reported somewhat more often in patient perspectives (65%) than in family perspectives (50%). Taking into account the limitations of the literature, further research is needed on the impact of divergent perspectives on end-of-life care. Dialogues among the stakeholders for each individual must occur to ensure a good death from the most critical viewpoint—the patient’s.

Keywords: successful dying, good death, aging, hospice, palliative care, caregivers

INTRODUCTION

“The truth is, once you learn how to die, you learn how to live.”

—Mitch Albom, Tuesdays with Morrie1

Considerable lay literature describes positive approaches to dying. For example, in “Tuesdays with Morrie”1 Mitch Albom visits with his former Sociology professor, Morrie Schwartz, who provides lessons on acceptance, communication, and love in the midst of his own dying process. Similarly, Viktor Frankl’s “Man’s Search for Meaning”2 describes experiences in a Nazi concentration camp that led to finding meaning during times of suffering and death. Also, in “The Last Lecture,”3 Randy Pausch discusses, after being diagnosed with advanced pancreatic cancer, how to truly live and embrace every moment because “time is all you have…and you may find one day that you have less than you think.” Finally, in his commencement speech at Stanford University, Steve Jobs,4 after a recent diagnosis of cancer, called death “very likely the single best invention of life” and described focusing on what was most important and meaningful to him as he confronted death. These literary examples illustrate various constructs of a good death or “dying well.”5

Within the healthcare community and, more specifically, in hospice and palliative care, there has been some discussion of the concept of a good death.6,7 This concept arose from the hospice movement and has been described as a multifaceted and individualized experience.8 According to an Institute of Medicine report published 19 years ago, a good death is one that is “free from avoidable distress and suffering for patient, family, and caregivers, in general accord with the patient’s and family’s wishes, and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards.”9 This concept has received some critique in several disciplines, including medicine, psychology, theology, sociology, and anthropology.6 In particular, concern has been raised that there is no such thing as an external criterion of a good death and that it is more dependent on the perspectives of the dying individual.10

In this article we use the terms “good death” or “successful dying.” Is successful dying an extension of successful aging? Research on successful aging has grown considerably in recent years;11 however, there is little agreement as to what specifically constitutes a good death or successful dying despite many reviews examining the concept of a good death from sociological and philosophical viewpoints12–18 as well as research examining the quality of death and dying, which is defined as “the degree to which a person’s preferences for dying and the moment of death agree with observations of how the person actually died, as reported by others.”19–23 However, far fewer studies have specifically defined, rather than conceptualized, what a good death is according to patients, family members, and healthcare providers (HCPs). The goal of this article is to review the literature that examined the definitions of a good death from the perspectives of such patients, their family members, and HCPs.

By examining the perspectives regarding a good death contrasted across different stakeholders, our aim is to identify potential unmet needs of patients and to suggest an approach to achieve a multifaceted and individualized experience for patients approaching death. Because a dearth of literature examines this important topic, our review is limited by the quantity and quality of studies available to evaluate. To our knowledge, no review to date has examined and compiled definitions of good death as defined explicitly by patients, family members, and HCPs or examined the differences among these stakeholders’ viewpoints. This is an area of considerable public health significance and impact on the patients, their families, and the overall healthcare system. The present article is also intended to serve as a call to action to highlight the need for more patient-focused research and open public dialogues on successful dying.

METHODS

Data Sources

We searched PubMed and PsycINFO databases from inception through November 2015 using the following terms: (definition of) AND (good OR successful OR peaceful) AND (Death OR Dying); (good) OR (successful OR peaceful) AND (“Death and Dying”); (“Terminal Care”[Mesh] AND “Quality of Life”[Mesh] AND “Attitude to Death”[Mesh]); (“Terminal Care”[Mesh]) AND “Attitude to Death”[Mesh] AND (define OR definition); good death and dignity; good death and end of life preferences; good death and quality of death and dying.

Selection of Articles

We restricted our search to include articles that met the following criteria: published in English in peer-reviewed journals and provided quantitative or qualitative data that specifically defined or used a measure of good death as the main aim or outcome of the study. We eliminated all duplicate articles from these searches. Additionally, we reviewed the reference lists of all articles that were relevant as well as recent review papers that examined a good death.15,24,25 There were no instances of overlapping samples.

Two authors (EAM and JVG) independently searched PubMed and PsycINFO databases for appropriate articles according to the key words mentioned above. Individual articles were independently coded for themes and subthemes by the two authors. If there was a disagreement between the two, a third author (DVJ) was consulted to help reach a consensus. Specific information about each article was stored in an Excel database.

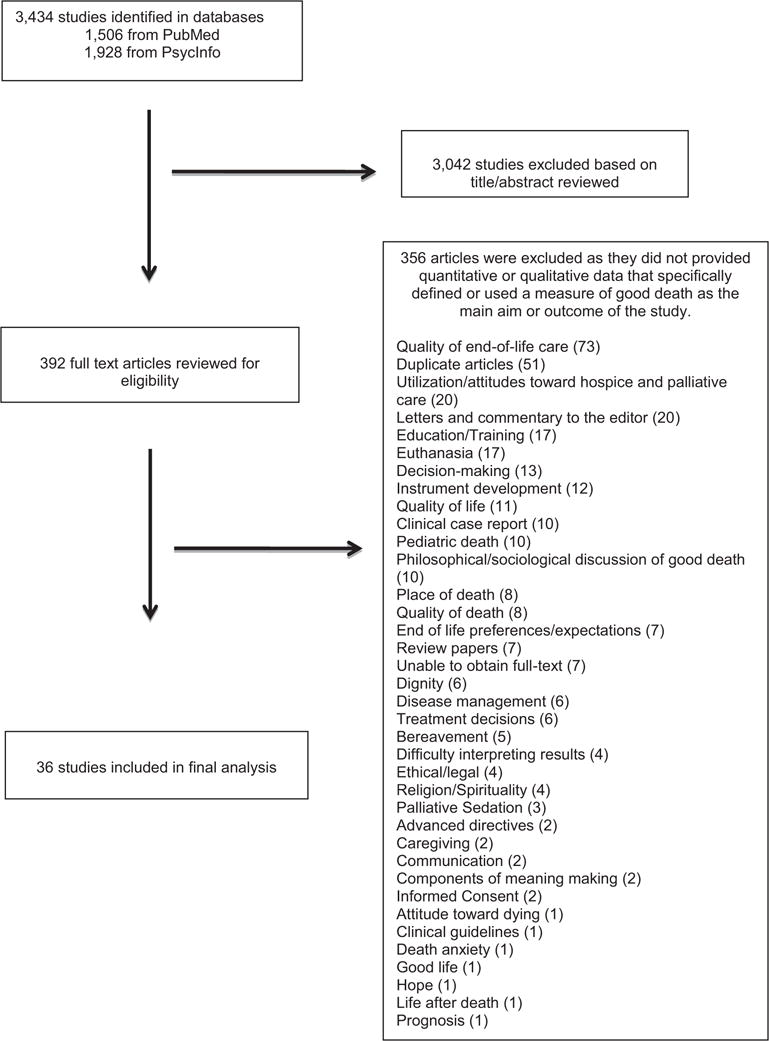

Most initial search results (3,434) were excluded because of irrelevance to the subject matter in the title or abstract (e.g., “good cell death,” “good bone death,” “animal death,” etc.), which resulted in 392 articles for further review. After a more detailed examination, we narrowed these articles down to 36 relevant to the present review (Fig. 1). Articles were excluded if they were focused solely on euthanasia or assisted suicide or on specific methods of enhancing quality of care at the end of life, unless one of the specific aims of the study was to define good death or successful dying.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the review process.

References from review papers of a good death were examined in detail to see if they met our inclusion criteria. Twenty-seven articles contained qualitative methods, 5 articles used quantitative methods, and 4 articles contained mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative). Of the quantitative and mixed-methods studies (N = 9), 3 articles used standardized measures of a good death, including the Preferences about Death and Dying questionnaire,26 The Concept of a Good Death scale,27 and The Good Death Inventory.28 The other six studies had developed their own quantitative measures (e.g., attitudinal measures of a good death);29 a 12-item questionnaire based on 12 principles of a good death according to the Future of Health Care of Older People report;30,31 a 57-item questionnaire based on a previous qualitative study;32 44 items of attributes important at the end of life developed from focus groups and in-depth interviews with patients, family members, and HCPs;33 and a 72-item survey on perceptions of end-of-life care.34

Coding of Articles

Two authors (EAM and JVG) independently read all 36 articles. We used the method of coding consensus, co-occurrence, and comparison outlined by Williams et al.35 and rooted in grounded theory to generate common themes of a good death. Four consensus meetings were held between two coders (EAM and JVG) to create the final coding scheme after resolving any disagreements. We began with 38 themes, which were narrowed to 11 themes in a consensus meeting involving three authors (EAM, JVG, and DVJ). Two authors (EAM and JVG) then independently coded each definition supplied in the 36 articles, which were then mapped onto the 11 core themes. If an item did not fit, it was placed in the “Other” core theme. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for the independent raters by use of the kappa statistic. The inter-rater reliability for the coders was kappa = 0.896 (p < 0.0.000; standard error: 0.023), which was a satisfactory level of agreement.36 Discrepancies were further discussed by two authors (EAM and JVG), with a third author (DVJ) consulted, when needed, to reach a final consensus on each definition.

The sources of each definition were separated into three groups: (1) patients’ perspectives (N = 20), (2) prebereaved and bereaved family members’ perspectives (N = 10), and (3) HCPs’ perspectives (N = 18). Patient populations consisted of those with advanced cancer, chronic illnesses, HIV/AIDS, as well as the general population. Family members’ perspectives were prebereavement (N = 1) or postbereavement (N = 9). HCPs included physicians, nurses, social workers, and spiritual counselors. HCP perspectives could not be further broken down into specific subgroups (e.g., physicians versus nurses) because these subgroups were usually combined in the studies reviewed. Of the 36 reviewed articles, 29 were coded into one category and 7 were coded into more than one group, 2 articles coded into two groups, and 5 articles were coded into all three.

Analyses

We did not conduct a formal meta-analysis in light of differences among the studies in terms of depth of information and methods used to assess stakeholders’ (especially patients’) demographics, medical diagnoses, treatment status, cognitive assessment, and so on. By definition, meta-analysis comprises statistical methods for contrasting and combining results from different studies in the hope of identifying patterns among study results, sources of disagreement among those results, or other interesting relationships that may come to light in the context of multiple studies (p. 652).37 This type of analysis was not possible for our data for the reasons mentioned above. Additionally, weighting was not done because qualitative and quantitative studies were combined. However, because all studies provided stakeholder frequency of responses that endorsed specific themes of a good death, we were able to aggregate frequencies across studies to calculate the mean percentages for different domains of what is perceived to be part of a good death. As such, we calculated the means and standard deviations or percentages, as appropriate, and reported the rate of endorsement of each of the 11 codes within each of the sources (e.g., patients, family members, and HCPs).

RESULTS

In total, 36 articles met our search criteria. These studies were published between 1996 and 2015. Total sample sizes across all studies reviewed ranged from 3 to 2,548 (mean: 184.4; standard deviation: 440.8). As one may expect, qualitative studies had much smaller sample sizes than quantitative investigations. Table 1 summarizes demographics of the patients included in individual studies. The age range of patients spanned 14–93 years (mean: 89.7; standard deviation: 16.6), with 50% of patient perspective articles including individuals over age 60 years. Age was somewhat skewed because several articles only reported a range rather than the mean age. There was a relatively even distribution between men and women across all studies. The studies reviewed had been conducted in the United States (N = 13), United Kingdom (7), Japan (3), Netherlands (3), Thailand (2), Iran (1), Israel (1), Canada (1), Nova Scotia (1), Saudi Arabia (1), South Korea (1), and Sweden (1), Turkey (1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients in the 36 Articles Reviewed for Successful Dying

| Study Authors and Year |

Country | Design/ Methods |

Measure of a Good Death | Diagnosis/ Population |

Age (y) | Gender | Ethnicity/Race | No. of Patients |

No. Family Members |

No. of HCPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payne (1996)38 | UK | Qualitative | Elicit (patient and palliative care professionals perception of death) | Advanced cancer | Range: 30–81 | 50% Male | — | 18 | — | 20 |

| Payne and Hillier (1996)39 | UK | Qualitative/quantitative | Narratives from participants used to define a “good death” | Cancer/hospice | Mean: 66 | 50% Male | — | 67 | — | — |

| Leichtentritt (2000)40 | Israel | Qualitative | Interviewing discussing good death | General population and medical patients | Range: 60–86 | 57% Female | Israelis | 26 | — | — |

| Steinhauser (2000)41 | USA | Quantitative | Survey (rank 44 attributes important at end of life) | Veterans with advanced chronic illness | Mean: 68 | 78% Male | 69% Non-Hispanic, White | 340 | 332 | 361 |

| Steinhauser (2000)33 | USA | Qualitative | Discuss (experiences with deaths of family members, friends, or patients and reflect on what made those deaths good) | Oncology and HIV | Range: 26–77 | 36% Male | 70% Non-Hispanic, White | 14 | 4 | 57 |

| Pierson (2002)42 | USA | Qualitative | Describe a (good death) | AIDS | Mean: 41 | 91% Male | 69% Non-Hispanic, White | 35 | — | — |

| Vig (2002)43 | USA | Qualitative | Open-ended questions assessing patients views of end of life | Cancer and heart disease | Range: 60–84 | 87% Female | — | 16 | — | — |

| Tong (2003)44 | USA | Qualitative | Focus groups to elicit views about death and dying | General population | Range: 14–68 | 67% Female | 53% Non-Hispanic, White 23% Black 14% Hispanic |

95 | — | — |

| Vig (2004)45 | USA | Qualitative | Open-ended questions assessing patients views of end of life | Cancer and heart disease | Mean: 71 | 100% Male | — | 26 | — | — |

| Goldstein (2006)46 | Amsterdam | Qualitative | Open-ended question interview to explore a “good death” | Cancer patients | Range: 39–83 | 70% Male | Non-Hispanic, White | 13 | — | — |

| Hirai (2006)47 | Japan | Qualitative | Asked participants for components of a “good death” | Cancer patients | Mean: 62 | 54% Male | — | 13 | 10 | 40 |

| Rietjens (2006)48 | Netherlands | Qualitative | Respondents were asked to indicate how important they considered 11 attributes of the dying process | General population | Range: 20–93 | 61% Female | — | 1,388 | — | — |

| Lloyd-Williams 2007)49 | UK | Qualitative | Semistructured interview based on concepts of independence, health, and well-being, societal support; theme of end of life reported in article | Community-dwelling adults | Range: 80–89 | 40% Male | 85% English | 40 | — | — |

| Miyashita (2007)32 | Japan | Quantitative | Asked subjects about the relative importance of 57 components of a good death | General population | Range: 49–70 | 48% Male | — | 2,548 | 513 | — |

| Gott (2008)50 | UK | Qualitative | Interviews to explore extent that older adult views are consistent with palliative care “good death” model | Advanced heart failure and poor prognosis | Mean: 77 | 53% Male | 40 | — | — | |

| Hughes (2008)8 | USA | Qualitative | Definition of good death | Lung cancer | Range: 24–85 | 50% Male | — | 100 | — | — |

| De Jong (2009)51 | Nova Scotia | Qualitative | Hear stories of good and bad deaths from those directly involved in palliative care | Palliative patients | — | — | — | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| Tayeb (2010)30 | Saudi Arabia | Qualitative/Quantitative | Principles of good death; agree or disagree with Western principles of good death | Hematology/oncology patients | — | 58% Male | Non-Saudi Arabian | 26 | 77 | 181 |

| Hattori (2012)52 | USA | Qualitative | Interviews asking “What does a good death mean to you? | Japanese older adults living in Hawaii | Mean: 78 | 77% Female | Japanese | 18 | — | — |

| Reinke (2013)26 | USA | Qualitative/Quantitative | In-person interview and questionnaire to rate what is most important in last 7 days of life | Veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Mean: 69 | 97% Male | 291 White | 376 | — | — |

Themes and Subthemes of Successful Death Definitions

Eleven themes were identified, and each consisted of 2 to 4 subthemes, which are presented in Table 2. The most frequently appearing theme for a good death across all groups was “preferences for the dying process,” which was reported in 94% of the articles in the sample. These preferences for the dying process included the following subthemes: the death scene (how, who, where, and when), dying during sleep, and preparation for death (e.g., advanced directives, funeral arrangements). “Pain-free status” was the second most frequent core theme of good death in the sample (81%) followed by “emotional well-being” (64%). Examples from patients included the following statements: “Painless. I mean pain is my biggest fear, you know. I don’t want to die in pain,” “a good death would be having the things that you wanted to have taken care of before you die done so you can be at peace with it.”42 Additionally, some statements included that thinking about death and dying made individuals feel “afraid and depressed.”50

TABLE 2.

Core Themes and Subthemes of a Good Death and/or Successful Dying

| Core Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| Preferences for dying process | Death scene (how, who, where, and when) |

| Dying during sleep | |

| Preparation for death (e.g., advanced directives, funeral arrangements) | |

| Pain-free status | Not suffering |

| Pain and symptom management | |

| Emotional well-being | Emotional support |

| Psychological comfort | |

| Chance to discuss meaning of death | |

| Family | Family support |

| Family acceptance of death | |

| Family is prepared for death | |

| Not be a burden to family | |

| Dignity | Respect as an individual |

| Independence | |

| Life completion | Saying goodbye |

| Life well lived | |

| Acceptance of death | |

| Religiosity/spirituality | Religious/spiritual comfort |

| Faith | |

| Meet with clergy | |

| Treatment preferences | Not prolonging life |

| Belief that all available treatments were used | |

| Control over treatment | |

| Euthanasia/physician-assisted suicide | |

| Quality of life | Living as usual |

| Maintaining hope, pleasure, gratitude | |

| Life is worth living | |

| Relationship with HCP | Trust/support/comfort from physician/nurse |

| Physician comfortable with death/dying | |

| Discuss spiritual beliefs/fears with physician | |

| Other | Recognition of culture |

| Physical touch | |

| Being with pets | |

| Healthcare costs |

Four themes—life completion, treatment preferences, dignity, and family—were endorsed by more than 50% of all three stakeholder groups (Table 3). The theme of life completion contained subthemes of saying goodbye, feeling that life was well lived, and acceptance of impending death. Treatment preferences included subthemes related to not prolonging life, a belief that all available treatments were used, a sense of control over treatment choices, and euthanasia/physician-assisted suicide. The theme of dignity consisted of being respected as an individual and maintaining independence, whereas the theme of family included family support, family accepting of death, the family is prepared for the death, and not being a burden to family.

TABLE 3.

Number of Articles (N = 36) that Included Specific Core Themes

| No. of Articles on Patients (N = 20) | No. of Articles on Prebereaved/Bereaved Family (N = 10) | No. of Articles on HCPs (N = 18) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferences for dying process | 20 (100) | 10 (100) | 17 (94) |

| Pain-free status | 17 (85) | 9 (90) | 15 (83) |

| Religiosity/spirituality | 13 (65) | 5 (50) | 9 (59) |

| Emotional well-being | 12 (60) | 7 (70) | 12 (67) |

| Life completion | 11 (55) | 8 (80) | 10 (56) |

| Treatment preferences | 11 (55) | 7 (70) | 11 (61) |

| Dignity | 11 (55) | 7 (70) | 12 (67) |

| Family | 11 (55) | 7 (70) | 11 (61) |

| Quality of life | 7 (35) | 7 (70) | 4 (22) |

| Relationship with HCP | 4 (20) | 4 (40) | 7 (39) |

| Other | 8 (40) | 4 (40) | 5 (28) |

Note: Values in parentheses are percent of the stakeholders endorsing themes.

Prebereaved and bereaved family members rated eight of the core themes at 70% and higher, the most frequent themes being preferences for dying process (100%), pain-free status (90%), and life completion (80%). Relationship with HCPs was found to be the least important specific theme among all three stakeholders.

Among HCPs, preference for dying process (94%) was the most frequently endorsed core theme of a good death, followed by pain-free status (83%), dignity (67%), and emotional well-being (67%). HCPs had the lowest endorsement for three core themes: life completion (56%), relationship with HCPs (39%), and quality of life (22%). Examples from HCPs included statements such as “having a patient pass quietly so not to disturb other patients,” “having the death occur at a time when there was adequate staff,” and “not having used excessive or futile treatments.”53,54 Some statements included regret for administered treatment or a concern that the medical staff was unable to provide appropriate care.

Differences in frequencies of themes among the stakeholder groups were greatest for quality of life, which was rated more frequently in family perspective articles (70%) than in patient and HCP perspective articles (35% and 22%, respectively) (Table 3). Similarly, prebereaved and bereaved family members identified the importance of family and maintaining dignity at a rate (70%) somewhat higher than that in the patient perspective articles (55% each). In contrast, religiosity/spirituality was endorsed somewhat more in patient perspective articles (65%) than in family perspective articles (50%). Supplementary Table S1 lists core themes endorsed by each stakeholder group in individual articles.

DISCUSSION

In this review we identified a number of themes important to a good death that both converge and diverge across stakeholders. To our knowledge, this review is the first systematic attempt to review the empirical literature on both the definition of a good death or successful dying according to patients, family members, and HCPs and differences across these stakeholder perspectives. Our review identified a general consensus among patients, family members, and HCPs in regard to pain-free status and specific preferences for the dying process; however, there were some notable discrepancies, for example, family members rated quality of life as more important than patient and HCP articles.

This review has several limitations. The first challenge is the variability among the articles reviewed in reporting data such as respondent characteristics. There were no common measures of a “good death” used in different investigations, which limited our capacity to aggregate results for conducting a meta-analysis or meta-regression. There was also an imbalance in sample sizes across qualitative and quantitative studies. We restricted our search to English-language and peer-reviewed articles, which might have limited the scope of our review. Also, some differences in perspectives of different stakeholders discussed below are rather small in magnitude, compounded by the limited amount of published literature in this emerging area of empirical research; consequently, we were underpowered to make statistical comparisons across study groups.

Empirical research on what comprises a good death began only a couple of decades ago, and several aspects of the methodology used in previously published studies were suboptimal. Most articles reviewed did not report information regarding specific demographics of patients, including age, culture/ethnicity, diagnoses, study inclusion/exclusion criteria, and recruitment procedures. Additionally, there was no mention of the length of time between the interview or survey and the patients’ death, which might have an important impact on specific wishes, desires, and needs as one nears the end of life as well as perceptions of what constitutes a good death, which could change over time and as the process is experienced. In regards to the investigations of family members, most studies included postbereavement family members, and therefore perspectives of prebereavement family members were not well represented. Finally, HCPs were often grouped together in the reports, and it is not known what percentage of HCPs were physicians, nurses, social workers, spiritual counselors, and so on. Furthermore, there was little information on how many, if any, of these HCPs had directly cared for dying patients or received training in such care.

Despite these limitations, we were able to identify some consistency among the three stakeholder groups in their perceptions of what constituted a good death. In more than 85% of the articles reviewed, having patient-focused preferences for the dying process and being pain-free were key components of achieving a good death according to patients, prebereaved and bereaved family members, and HCPs. Physicians, nurses, and other HCPs viewed optimal pain control and keeping the patient comfortable as a requirement for a good death.17,29,33,51 This is also consistent with the overall philosophy of hospice and palliative care, which focuses on decreasing pain and suffering while improving quality of life for both patients and family members.55

Although family members’ perspectives seemed to be more in tune with the patients’ needs and desires for end-of-life care than HCPs’, there were also some differences between family members and patients in what themes they believed to be important for a good death. For example, quality of life was rated as an important component of a good death twice as often by family members (70%) as by patients (35%). Most family perspective articles were conducted with bereaved family members who were often asked to recall the death of a loved one. Although we cannot make assumptions regarding the inferences of these findings, it could be argued that family members and patients define quality of life differently. The quality of life literature is large and beyond the scope of this review; however, it is worth further investigating how patients, family members, and HCPs define quality of life near the end of life to help understand and define this construct more precisely.

Additionally, “dignity” was reported to be an important component of a good death in 70% of family articles compared with 55% of the articles that included patient perspectives. Although the difference is not large, the finding is counterintuitive to previous research, which has argued that patients greatly value maintaining dignity during the late phase of their life.56,57 However, definitions of dignity vary, and the concept of dignity may have been absorbed into other themes from the stakeholders’ perspectives. Over the last 17 years, The Oregon Death with Dignity Act has consistently publicized that the three most important concerns reported among patients near the end of their lives include a loss of autonomy (91%), a decrease in the ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (86%), and a loss of dignity (71%).58 Furthermore, in a study conducted in 2002 by Chochinov et al.,56 palliative care patients reported that “not being treated with respect or understanding” (87%) and “feeling a burden to others” (87%) significantly impacted their sense of dignity. Therefore, our findings do not necessarily mean that dignity is less important for dying patients but that perhaps patients have a difficult time expressing the need for or concept of dignity to others.

The role of religiosity/spirituality was also somewhat discrepant between patients and other groups. Nearly two-thirds of patients (65%) in the articles reviewed expressed a desire to have religious or spiritual practices fulfilled as a theme of a good death; in contrast, only 50% of family members rated this theme as important. It should be added that hospice care teams are typically supposed to be composed of physicians, nurses, home health aides, social workers, as well as clergy or spiritual counselors.59 However, in our current sample not all the patients were receiving hospice services, which might have contributed to a lack of recognition of the importance of religiosity/spirituality, because many organizations and hospitals do not have clergy members or spiritual counselors available on site, especially for diverse groups of patients.

Finally, although some literature exists on pain and physical symptoms, there is a dearth of research examining the psychological aspects of a good death, particularly from a patient perspective.12 Our review indicates that patients view emotional well-being as a critical component of a successful death, as do family members and HCPs. Although it is important that we attend to the patient’s physical symptoms and pain control, it is crucial that the healthcare system expand the care beyond treating these symptoms and more closely address psychological, social, and religiosity/spirituality themes in end-of-life care for both patients and families. Patients view the end of life as encompassing not only the physical components of death but also psychosocial and spiritual concerns.33 Both the American Psychological Association and the European Association for Palliative Care have identified a need for mental health professionals to address and measure psychological concerns at the end of life.60,61 Further research regarding the psychological components of a good death is needed, especially in developing effective screening measures and appropriate interventions for dying patients.12

Future Directions

This review suggests an obvious need for more research to examine the concept of a good death from patients’ perspectives to deliver quality care that is individualized to meet each patient’s needs8,62 as well as the needs of their families. The discrepancies among patient, family member, and HCP perspectives on successful dying in this review indicate a critical need for a dialogue about death among all stakeholders involved in the care of each individual patient. It is important that we not only understand but also further investigate how addressing the themes identified in this review, both convergent and discrepant among stakeholders, may influence patient-related outcomes.

Well-designed studies are also necessary to qualitatively and quantitatively examine the concept of successful dying according to patients themselves, because this would have the potential to influence HCP care practices and to help family members meet the needs of their dying loved ones. Qualitative research could lead to the development of measurement tools for successful dying that allow for real-time modifications in care and examine how specific diseases and interventions intersect values and beliefs that are most important to patients nearing the end of their lives. Future studies would also benefit from mixed qualitative–quantitative method designs that compare people at the end of life with others who have chronic but earlier stage diseases (e.g., heart or lung disease). Additionally, it would be important to include different age cohorts (young, middle-aged, and older adults) to determine whether age impacts the themes that constitute a good death. Investigations of large numbers of demographically, medically, and psychosocially well-characterized patients from diverse ethnic and cultural groups, using standardized and validated instruments for successful dying, and seeking perspectives of these patients along with their prebereaved and bereaved family members and HCPs are recommended to inform the best practices in caring for dying patients and their families. Finally, future studies should use a clearly delineated sampling strategy that would then allow generalization to a larger population of patients, family members, and HCPs.

Finally, an important goal of this review is to issue a call for action to the professional and lay community to accelerate its open dialogue regarding death and dying, as the United States has a largely “death-phobic” culture.63 Although individuals in many states in the country are formally asked and encouraged to consider advanced directives and organ donations, should we, as clinicians, also not ask our older patients to stipulate their preferences for the dying process? If, as a society, we begin to address the question of how people want to die and what they actually need and want at the end of their lives, perhaps we can enable more people to obtain a good death, reaching their full potential, with dignity and whole-person well-being. As stated eloquently by Gawande,7 “…our most cruel failure in how we treat the sick and the aged is the failure to recognize that they have priorities beyond merely being safe and living longer; that the chance to shape one’s story is essential to sustaining meaning in life; that we have the opportunity to refashion our institutions, our culture, and our conversations in ways that transform the possibilities for the last chapters of everyone’s lives.”

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research came, in part, from the Sam and Rose Stein Institute for Research on Aging at UC San Diego, American Cancer Society: MRSG-13-233-01 PCSM, and UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center.

APPENDIX: SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2016.01.135.

References

- 1.Albom M. Tuesdays with Morrie. New York, NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frankl V. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pausch R, Zaslow J. The Last Lecture. New York, NY: Hyperion; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jobs S. Commencement Address, presented at Stanford University Commencement Ceremony; Stanford, CA. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byock I. Dying Well: The Prospect for Growth at the End of Life. New York, NY: Riverhead Books; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granda-Camerson C, Houldin A. Concept analysis of good death in terminally ill patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012;29:632–639. doi: 10.1177/1049909111434976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gawande A. Being Mortal. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes T, Schumacher M, Jacobs-Lawson JM, et al. Confronting death: perceptions of a good death in adults with lung cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25:39–44. doi: 10.1177/1049909107307377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scarre G. Can there be a good death. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:1082–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeste DV, Depp CA, Vahia IV. Successful cognitive and emotional aging. World Psychiatry. 2010;9:78–84. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00277.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. The promise of a good death. Lancet. 1998;351(suppl 2):SII21–SII29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bosek MS, Lowry E, Lindeman DA, et al. Promoting a good death for persons with dementia in nursing facilities: family caregivers’ perspectives. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul. 2003;5:34–41. doi: 10.1097/00128488-200306000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart B, Sainsbury P, Short S. Whose dying? A sociological critique of the “good death. Mortality. 1998;3:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hattori K, McCubbin MA, Ishida DN. Concept analysis of good death in the Japanese community. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38:165–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNamara B. Good enough death: autonomy and choice in Australian palliative care. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:929–938. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNamara B, Waddell C, Colvin M. The institutionalization of the good death. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:1501–1508. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walter T. Historical and cultural variants on the good death. Br Med J. 2003;327:218–220. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR. Evaluating the quality of dying and death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:717–726. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downey L, Curtis JR, Lafferty WE, et al. The Quality of Dying and Death Questionnaire (QODD): empirical domains and theoretical perspectives. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis JR, Downey L, Engelberg RA. The quality of dying and death: is it ready for use as an outcome measure? Chest. 2013;143:289–291. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patrick DL, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, et al. Measuring and improving the quality of dying and death. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:410–415. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_2-200309021-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Engelberg RA, et al. A measure of the quality of dying and death: initial validation using after-death interviews with family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00419-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borreani C, Miccinesi G. End of life care preferences. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2008;2:54–59. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e3282f4cb27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kehl KA. Moving toward peace: an analysis of the concept of a good death. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23:277–286. doi: 10.1177/1049909106290380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reinke LF, Uman J, Udris EM, et al. Preferences for death and dying among veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30:768–772. doi: 10.1177/1049909112471579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gibson MC, Gutmanis I, Clarke H, et al. Staff opinions about the components of a good death in long-term care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2008;14:374–381. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2008.14.7.30772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyashita M, Morita T, Sato K, et al. Good death inventory: a measure for evaluating good death from the bereaved family member’s perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Vecchio Good MJ, Gadmer NM, Ruopp P, et al. Narrative nuances on good and bad deaths: internists’ tales from high-technology work places. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:939–953. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tayeb MA, Al-Zamel E, Fareed MM, et al. A “good death”: perspectives of Muslim patients and health care providers. Ann Saudi Med. 2010;30:215–221. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.62836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duyan V, Serpen AS, Duyan G, et al. Opinions of social workers in Turkey about the principles on die with dignity. J Relig Health. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyashita M, Sanjo M, Morita T, et al. Good death in cancer care: a nationwide quantitative study. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1090–1097. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, et al. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:825–832. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beckstrand RL, Callister LC, Kirchhoff KT. Providing a “good death”: critical care nurses’ suggestions for improving end-of-life care. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:38–45. quiz 46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams DG, Best JA, Taylor D. A systematic approach for using qualitative methods in primary prevention research. Med Anthropol Q. 1992;4:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payne S, Langley-Evans A, Hillier R. Perceptions of a good death: a comparative study of the views of hospice staff and patients. Palliat Med. 1996;10:307–312. doi: 10.1177/026921639601000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payne S, Hillier R, Langley-Evans A, et al. Impact of witnessing death on hospice patients. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:1785–1794. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leichtentritt RD, Rettig KD. The good death: reaching an inductive understanding. Omega (Westport) 2000;41:221–248. doi: 10.2190/2GLB-5YKF-4162-DJUD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierson CM, Curtis JR, Patrick DL. A good death: a qualitative study of patients with advanced AIDS. AIDS Care. 2002;14:587–598. doi: 10.1080/0954012021000005416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vig EK, Davenport NA, Pearlman RA. Good deaths, bad deaths, and preferences for the end of life: a qualitative study of geriatric outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1541–1548. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tong E, McGraw SA, Dobihal E, et al. What is a good death? Minority and non-minority perspectives. J Palliat Care. 2003;19:168–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vig EK, Pearlman RA. Good and bad dying from the perspective of terminally ill men. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:977–981. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.9.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldsteen M, Houtepen R, Proot IM, et al. What is a good death? Terminally ill patients dealing with normative expectations around death and dying. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:378–386. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hirai K, Miyashita M, Morita T, et al. Good death in Japanese cancer care: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rietjens JAC, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al. Preferences of the Dutch general public for a good death and associations with attitudes towards end-of-life decision-making. Palliat Med. 2006;20:685–692. doi: 10.1177/0269216306070241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lloyd-Williams M, Kennedy V, Sixsmith A, et al. The end of life: a qualitative study of the perceptions of people over the age of 80 on issues surrounding death and dying. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gott M, Small N, Barnes S, et al. Older people’s views of a good death in heart failure: implications for palliative care provision. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Jong JD, Clarke LE. What is a good death? Stories from palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2009;25:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hattori K, Ishida DN. Ethnographic study of a good death among elderly Japanese Americans. Nurs Health Sci. 2012;14:488–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2012.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Costello J. Dying well: nurses’ experiences of “good and bad” deaths in hospital. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54:594–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karlsson M, Milberg A, Strang P. Dying with dignity according to Swedish medical students. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:334–339. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0893-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Palliative Care Research. Why is palliative care research needed? Available at: http://www.npcrc.org/about/about_show.htm?doc_id=374985. Accessed July 16, 2012.

- 56.Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care—a new model for palliative care: helping the patient feel valued. JAMA. 2002;287:2253–2260. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:753–762. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oregon Death with Dignity. Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act—2014 Annual Report. Available at: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year17.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2015.

- 59.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. History of Hospice. Available at: http://www.nhpco.org/about/hospice-care. Accessed March 4, 2015.

- 60.American Psychological Association. Brochure on End of Life Issues and Care. Available at: http://www.apa.org/topics/death/end-of-life.aspx. Accessed June 13, 2012.

- 61.Junger S, Payne SA, Costantini A, et al. The EAPC task force on education for psychologists in palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care. 2010;17:84–87. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mak JM, Clinton M. Promoting a good death: an agenda for outcomes research: a review of the literature. Nurs Ethics. 1999;6:97–106. doi: 10.1177/096973309900600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Samuel LR. Death, American Style. 1st. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanson LC, Henderson M, Menon M. As individual as death itself: a focus group study of terminal care in nursing homes. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:117–125. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iranmanesh S, Hosseini H, Esmaili M. Evaluating the “good death” concept from Iranian bereaved family members’ perspective. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim S, Lee Y. Korean nurses’ attitudes to good and bad death, life-sustaining treatment and advance directives. Nurs Ethics. 2003;10:624–637. doi: 10.1191/0969733003ne652oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kongsuwan W, Chaipetch O, Matchim Y. Thai Buddhist families’ perspective of a peaceful death in ICUs. Nurs Crit Care. 2012;17:151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kongsuwan W, Keller K, Touhy T, et al. Thai Buddhist intensive care unit nurses’ perspective of a peaceful death: an empirical study. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2010;16:241–247. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2010.16.5.48145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.LeBaron VT, Cooke A, Resmini J, et al. Clergy views on a good versus a poor death: ministry to the terminally ill. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:1000–1007. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Low JT, Payne S. The good and bad death perceptions of health professionals working in palliative care. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 1996;5:237–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.1996.tb00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oliver T, O’Connor SJ. Perceptions of a “good death” in acute hospitals. Nurs Times. 2015;111:24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Gennip IE, Pasman HR, Kaspers PJ, et al. Death with dignity from the perspective of the surviving family: a survey study among family caregivers of deceased older adults. Palliat Med. 2013;27:616–624. doi: 10.1177/0269216313483185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.