Abstract

In mice, loss of pantetheinase activity causes susceptibility to infection with Plasmodium chabaudi AS. Treatment of mice with the pantetheinase metabolite cysteamine reduces blood-stage replication of P. chabaudi and significantly increases survival. Similarly, a short exposure of Plasmodium to cysteamine ex vivo is sufficient to suppress parasite infectivity in vivo. This effect of cysteamine is specific and not observed with a related thiol (dimercaptosuccinic acid) or with the pantethine precursor of cysteamine. Also, cysteamine does not protect against infection with the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi or the fungal pathogen Candida albicans, suggesting cysteamine acts directly against the parasite and does not modulate host inflammatory response. Cysteamine exposure also blocks replication of P. falciparum in vitro; moreover, these treated parasites show higher levels of intact hemoglobin. This study highlights the in vivo action of cysteamine against Plasmodium and provides further evidence for the involvement of pantetheinase in host response to this infection.

Keywords: Apicomplexa, Plasmodium, Cysteamine, Mouse model, Anti-parasitic

1. Introduction

Malaria causes an estimated 400–500 million clinical cases with 1–2 million deaths occurring annually (www.who.int). The problem is compounded by resistance of the Plasmodium malarial parasite to drugs (chloroquine, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, and more recently, artemisinin derivatives) accessible in developing countries where malaria is endemic (Hyde, 2007; Dondorp et al., 2009) and the appearance of insecticide-resistance in the Anopheles vector (Brogdon and McAllister, 1998). In addition, an effective vaccine against malaria does not yet exist (Moorthy et al., 2004); consequently, the study of potential new treatment approaches against this disease should be continuously pursued.

In malaria, the genetic make-up of the host plays an important role in initial susceptibility, disease progression, type of pathology developed and ultimate outcome of infection (Fortin et al., 2002a). Indeed, malaria is one of the rare examples of infectious disease where the pathogen has submitted its mammalian host to considerable selective pressure, with clear evidence of co-evolution [rev. in Kwiatkowski (2005)]. For example, otherwise deleterious genetic variants causing sickle cell anemia (HbS), α and β thalassemias, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, have been retained at high frequencies in populations living in regions of endemic malaria due to a protective effect of heterozygosity. Likewise, alterations in other red cell proteins (glycophorins (Maier et al., 2003), CD36 (Aitman et al., 2000), Duffy antigen (Miller et al., 1976)) also protect against malaria. Linkage and association studies suggest that the genetic component of malaria susceptibility is complex and heterogeneous in humans and modulated by environmental factors (Weatherall and Clegg, 2002).

Genetic studies of mouse models of blood stage (Plasmodium chabaudi AS) or cerebral (Plasmodium berghei ANKA) malaria provide additional avenues to identify and characterize genes modulating host response to Plasmodium (Fortin et al., 2002b). Up to 9 Char loci (chabaudi resistance) affecting susceptibility to infection by P. chabaudi AS, as measured by degree of parasite replication in blood, have so far been mapped [rev. in (Hernandez-Valladares et al., 2005)]. Using positional cloning, we have shown that the protective effect of the Char4 locus is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the erythrocyte form of pyruvate kinase (PklrI90N) (Min-Oo et al., 2003; Min-Oo et al., 2004). Likewise, we observed that homozygosity and heterozygosity for mutant alleles at the human PKLR gene also protect against Plasmodium falciparum malaria in erythrocytes ex vivo (Ayi et al., 2008). Studies of the Char9 locus (Fortin et al., 2001; Min-Oo et al., 2007) showed that lack of expression of pantetheinase-encoding Vnn1 and Vnn3 genes causes susceptibility to infection in A/J mice. Vnn1 codes for a GPI-anchored enzyme expressed in epithelial cells of the intestine, kidney and liver, while the Vnn3 protein appears to be secreted and is abundant in myeloid cells (Martin et al., 2001). Pantetheinases hydrolyze pantetheine (CoenzymeA pathway), recycling Vitamin B5 and producing the small aminothiol cysteamine, a potent anti-oxidant (Dupre et al., 1970). Vnn1 deficient mouse mutants have been shown to display reduced inflammatory response in the intestine and are protected against pathological consequences of either infectious (Schistosoma mansoni) or drug-induced inflammatory stimuli (Berruyer et al., 2004; Martin et al., 2004), a phenomenon that can be reversed by cystamine (cysteamine dimer).

Cysteamine (β-mercaptoethylamine) has potent anti-oxidant activity and modulates cellular levels of glutathione (Djurhuus et al., 1990), produces peroxides, interacts with cysteines (Gahl et al., 1985) and inhibits a variety of enzymes, such as transglutaminases (Jeon et al., 2004). Both cyteamine and cystamine have been shown to be cytoprotective and may also sequester toxic reactive aldehyde products (Wood et al., 2007). Cysteamine is in clinical use for the life-long treatment of cystinosis, an inherited disorder (autosomal recessive) caused by mutations in cystinosin, a gene encoding a cystine lysosomal exporter (Kalatzis et al., 2001). When daily oral therapy is administered starting at childhood, cysteamine depletes cells of lysosomal cystine and delays the renal complications of cystinosis (Gahl, 2003).

We have explored the potential anti-parasitic properties and specificity of cysteamine in a mouse model of blood stage infection with P. chabaudi and in human P. falciparum in vitro.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice and P. chabaudi AS Infection

A/J and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and were housed at McGill University according to the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. An LDH virus-free isolate of P. chabaudi AS was maintained by weekly passage in A/J mice. Mice were infected intravenously into the tail vein (i.v.) with 105 pRBC suspended in pyrogen-free saline. Following infection, the percentage of pRBC was determined daily, as described (Fortin et al., 2001).

2.2. Cystamine/cysteamine, pantethine and DMSA administration

Cystamine dihydrochloride and cysteamine hydrochloride (Sigma, Burlington ON) were prepared in PBS. DMSA (meso 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid) (Sigma, Burlington ON) was prepared in sterile water and the pH was adjusted to 7 by addition of NaOH. Pantethine (Sigma, Burlington ON) was prepared in PBS. All solutions were prepared fresh daily and injections were performed intra-peritoneally (i.p.) for 8–14 days, depending on regimen. Untreated control animals were injected with PBS alone.

2.3. Serum cytokine measurements

Serum was obtained from female A/J mice at day 5 or day 7 post-infection with P. chabaudi AS, treated or not with cysteamine (120 mg/kg in a prophylactic regimen). Determination of serum levels of IFNγ, MCP-1, VEGF, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, MIP-1β, RANTES, TNF was performed by the CytokineProfiler® Testing Service (Millipore, Inc., St. Charles, MO, USA) using a Multiplex Assay Platform.

2.4. Ex vivo treatment of P. chabaudi by cysteamine

On day 0, pRBCs from a passage animal were counted and diluted. 0.5 mL (1 × 106 pRBC) was distributed into four tubes and mixed with 0.5 mL of 2× solutions of cysteamine–HCl (0, 400, 800 and 1600 μ.M). Ex vivo exposure to cysteamine solution was performed for 1 h at 37 °C, and the drug was washed off. Subsequently, groups of mice (four males, four females) were infected i.v. with 1 × 105 pRBCs from each of the pRBCs–cysteamine solutions. Parasitemia was followed on daily blood smears from day +4 to day +8.

2.5. Trypanosoma cruzi and C. albicans infections

A/J mice were infected with 1000 blood–borne trypomastigotes of T. cruzi (Y strain) at night by intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injection. Treatment was performed daily with i.p. injections of 150 mg of cysteamine hydrochloride (CysH) per kg of body weight in 0.2 mL of volume, beginning two days prior to infection. Controls received 0.2 mL of vehicle (PBS). Parasitemia was assessed from 5 μL of blood obtained from the tail vein, according the Brener method (Brener, 1962). C. albicans strain SC5314 was grown overnight in YPD medium [1% yeast extract, 1% Bacto Peptone (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Michigan) and 2% dextrose (Sigma, Burlington ON)] at 30 °C and harvested by centrifugation. The blastospores were washed twice in PBS and re-suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at the required density. For experimental infections, male and female A/J mice were injected via the tail vein with a 200 μL of suspension of 3 × 105 C. albicans blastospores in PBS. CysH treatment (intra-peritoneal) was administered daily (120 mg/kg) starting 48 h prior to infection and until 1 day post-infection. For determination of fungal loads, target organs were removed aseptically at 24 h post-infection and homogenized in 5 mL PBS. Fifty microliters of an appropriate dilution was plated on Sabouraud broth-agar plates containing 0.35 mg/L chloramphenicol, followed by incubation at 30 °C for 48 h. Mice infected with T. cruzi or C. albicans were closely monitored for clinical signs such as lethargy, loss of appetite, hunched back and ruffled fur. Mice exhibiting extreme lethargy were deemed moribund and were euthanized.

2.6. P. falciparum in vitro growth studies

P. falciparum ITG chloroquine-resistant and 3D7 chloroquine-sensitive (mycoplasma-free) clones were maintained in continuous culture as previously described (Trager and Jensen, 1976). Mature forms were purified and used to infect fresh RBCs (Ayi et al., 2004). To assess anti-malarial activity of the drugs, two methods were used: SYBR-green method to quantify parasite genomic DNA (Smilkstein et al., 2004) and microscopic analysis to follow merozoite invasion and maturation. 1. SYBR-green method: Briefly, a 96-well plate with a series of two-fold dilutions was produced containing R-10G plus drug and R-10G alone (last well). The parasite culture, 1% hematocrit and 2% parasitemia, was added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37 °C and gassed (93% N2, 5% CO2 and 2% O2) for 48 h. Relative fluorescence was assessed using a Fluostar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtech, Offenburg, Germany). 2. Microscopic analysis: The inoculum was prepared by mixing separated mature forms with fresh RBCs suspended in growth medium. For each culture, a volume of 5 mL with 1% hematocrit was maintained in sterile flasks and treated with CysH or Cys. Final parasitemia was adjusted at 1%, the flasks were maintained at 37 °C and gassed. Slides were prepared from cultures at indicated times, stained with Diff-Quik, and 1000 cells examined microscopically and expressed as percentage of parasitized cells.

2.7. Glutathione and ATP measurements in erythrocytes

Glutathione and adenosine triphosphate levels were measured in erythrocytes treated with varying concentrations of either cysteamine or cystamine. Reduced glutathione was measured according to the method of Beutler (1984) after incubation at 37 °C for 24, 48 and 72 h with the compounds. Briefly, 10 μL of packed erythrocytes were lysed with cold distilled water (1:10), precipitated with 1.67% (w/v) metaphosphoric acid (1:3) on ice for 5 min. Cell extracts were centrifuged and supernatant neutralized with 0.3 M Na2HPO4 (2:3). GSH level was assessed in neutralized extract with 5,5-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (1:5 dilution) in a spectrophotometer at 405 nm and expressed in nmol of GSH/107 RBCs. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels were measured using a bioluminescence assay (FL-ASC, Sigma, Burlington ON) after 48 h of incubation with the compounds, according to the manufacturer. Briefly, cell suspensions at 1% hematocrit were lysed with somatic cell lysis buffer (1:10) for 1 min and diluted. Luciferin-luciferase reagent was added to the cell extract at a ratio of 1:1 and light emission was read immediately. ATP level is expressed as relative luminescence units.

2.8. Immunoblotting for human hemoglobin

P. falciparum ring stage infected human RBCs were treated or not, for 18 hours with CysH (150 μM), Cys (75 μM) or chloroquine (20 nM), or with combinations (10 nM chloroquine and 100 μM CysH or 10 nM chloroquine and 50 μM Cys). RBCs were lysed and parasites were washed 4× in cold PBS to remove excess hemoglobin. Parasite pellets were solubilized in SDS–PAGE sample buffer and 5 μL aliquots were resolved on a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel, followed by transfer onto nitrocellulose and immunoblotting with a 1:5000 dilution of rabbit anti-human hemoglobin antiserum (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The membrane was then incubated with HRP-goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:20,000), washed in TBS-T (0.1% Tween-20) and visualized by chemiluminescence. Quantification of the immunoblot was done using the ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij).

2.9. Statistical tests

Groups with normally distributed data points were compared using parametric unpaired t-tests, while groups with non-Gaussian distributions were compared using non-parametric Mann–Whitney tests. Survival differences were analyzed using the Log-Rank test.

3. Results

3.1. Cysteamine treatment reduces blood parasitemia and increases survival of P. chabaudi-infected mice

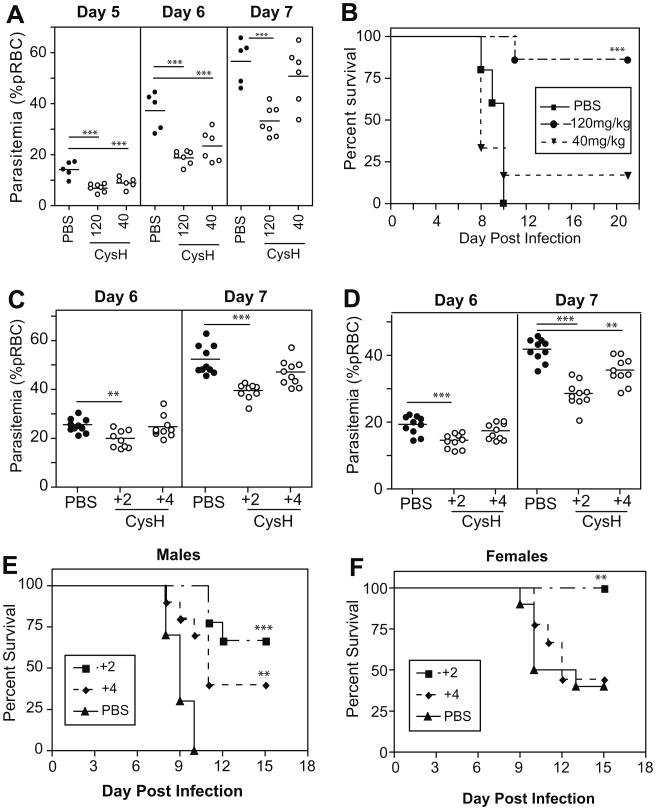

We have previously shown a role for pantetheinase in the control of parasite replication in mice infected with P. chabaudi, in a blood-stage model of infection (Min-Oo et al., 2007). To build upon these initial findings, we tested the anti-malarial activity of cysteamine (CysH), the reduced thiol form of cystamine, in malaria-susceptible A/J mice infected with P. chabaudi (105 pRBC i.v.) in vivo. We used a prophylactic protocol, with CysH administered daily (i.p.; 120 mg/kg or 40 mg/kg) starting 2 days prior to, and continuing for 12 days following infection. Fig. 1A shows that treatment with either 120 mg/kg or 40 mg/kg of CysH caused significant reductions in early parasite burden (p < 0.0001 at day 6 and 7, p = 0.005 at day 6 for high and low dose, resp.), compared to PBS-treated controls. More remarkably, the reduction in parasite levels significantly increased survival of animals treated with high dose CysH (80% survival; p = 0.0007), while a modest increase in survival was also noted for low dose CysH treatment (Fig. 1B). Similar and highly significant beneficial effects on blood-stage parasitemia and overall survival were observed when cystamine (Cys) was used in this prophylactic treatment protocol (Figure S1A/B). We also assessed whether CysH could exhibit anti-parasitic activity when given after the development of patent parasitemia. Mice were infected with P. chabaudi AS and therapeutic treatment with CysH (120 mg/kg) was commenced at 2 or 4 days post-infection. In male mice receiving treatment 2 days after infection, there was a significant reduction in parasitemia, at day 6 (p = 0.0014; t-test) and 7 (p < 0.0001; t-test); treatment starting at day +4 only resulted in modest decreases in parasitemia (Fig. 1C). Treatment of males dramatically improved survival to 67% (day +2; p < 0.0001; Log-Rank Test) and 35% (day+ 4; p = 0.0018; Log-Rank Test) compared to controls (0% survival) (Fig. 1E). In females, CysH treatment commencing at day 2 caused a reduction in parasitemia measured at days 6 and 7 (p = 0.0004, p < 0.0001 resp.; unpaired t-test), while treatment from day 4 onwards also decreased parasitemia levels by day 7 (p = 0.0015; unpaired t-test) (Fig. 1D). Survival of female mice only improved when treatment was started at day 2 (p = 0.0042; Log-Rank Test), in which case 100% of the animals recovered from the infection, compared to only 35% of controls (Fig. 1F). In all cases, Cys or CysH treatment alone had no adverse effect or obvious toxicity on experimental animals. These results suggest that CysH, given prior to or after the onset of infection, has a protective effect against malaria in highly susceptible A/J mice. This may involve a rapid modulation of host response, a directly toxic effect on the parasite, or both.

Fig. 1.

The effect of cysteamine treatment on P. chabaudi infection in vivo. A/J mice were treated with CysH, infected with P. chabaudi (105 pRBC i.v.) and monitored for parasitemia. (A) Parasite levels after prophylactic treatment with CysH (120 or 40 mg/kg) compared to PBS-injected controls, for female mice. Kaplan–Meier survival curves of treated and untreated mice are plotted in (B). Parasitemia levels from therapeutic cysteamine treatment starting at day +2 or day +4 are shown for males (C) and females (D), while survival is plotted in (E and F) for the same groups. Each dot represents a mouse. Statistically significant differences (unpaired t-test) are indicated by asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

3.2. Cysteamine treatment does not increase early pro-inflammatory cytokines

Studies of Vnn1−/− mice suggested that CysH up-regulates inflammatory response (Martin et al., 2004; Berruyer et al., 2004). To test if enhancement of inflammatory response underlies the beneficial effect of CysH, the levels of key cytokines and chemokines were measured 5 and 7 days post-infection with P. chabaudi. As expected, blood parasitemia is lower in CysH-treated mice compared to controls (Table 1). In CysH treated but uninfected control mice, we could not detect any of the assayed serum cytokines (data not shown); likewise, IL-12p40, IL-12p70 or VEGF were undetectable in all of the experimental groups (data not shown). Response to P. chabaudi infection was associated with appearance of serum IFNγ, IL-10, MCP-1, MIP1β, TNF and RANTES. At day 5, CysH-treated mice showed lower levels of IFNγ and MCP-1 and IL-10 than controls (Table 1), while, in general, all cytokine and chemokine levels increased at day 7, indicating progression of infection (Table 1). These results indicate that there is no major up-regulation of serum cytokines following administration of cysteamine; rather, the intensity of cytokine response appears to reflect the size of the parasite burden in the infected animals. These findings suggest that CysH does not enhance early host inflammatory response and may have a more direct anti-parasitic effect.

Table 1.

Cytokine response following P. chabaudi infection in cysteamine treated mice.

| Cytokine | Detection threshold (pg/ml) | Day 5 | Day 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Mean (range) in pg/ml | Mean (range) in pg/ml | ||||

|

|

|

||||

| Untreated | Treated | Untreated | Treated | ||

| IFNγ | 14 | 266 (180–329) | 24 (14–45) | 146 (60–273) | 140 (96–193) |

| TNF | 14 | 17 (14–22) | 14 (14) | 49 (21–79) | 32 (15–45) |

| RANTES | 54 | 54 (54) | 59 (54–79) | 106 (54–137) | 68 (54–82) |

| MCP-1 | 54 | 312 (215-490) | 75 (54–116) | 1068 (116–2781) | 3064 (503–10000) |

| MIP1β | 36 | 52 (36–97) | 51 (36–80) | 82 (36–143) | 95 (68–141) |

| IL-10 | 14 | 51 (21–91) | 14 (14) | 679 (338–1171) | 787 (69–1433) |

| Parasitemia* | 8.6 (6.3–11.8) | 3.9 (0.5–4.0) | 35.6 (34.3–48.3) | 17.8 (11.3–25.5) | |

Values in bold represent significant differences (p < 0.05).

Parasitemia is expressed in percentage of parasitized red cells (pRBC).

3.3. The effect of cysteamine on P. chabaudi infectivity after exposure ex vivo

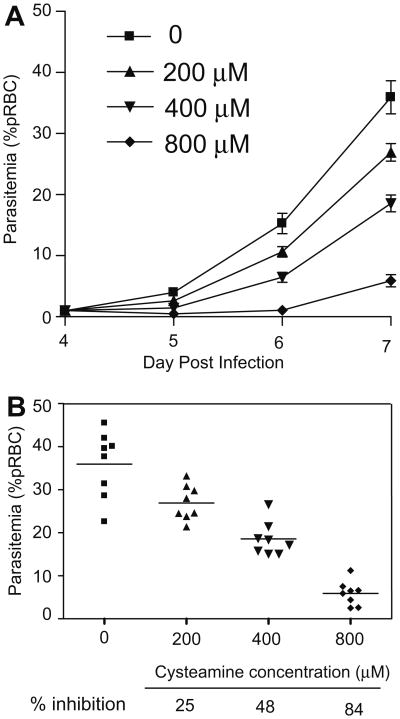

We investigated whether CysH could have a direct anti-parasitic effect ex vivo, by exposing P. chabaudi parasitized red blood cells (pRBCs) to CysH for a period of time and determining the effect of this exposure on the ability of the treated preparation to induce infection in a naïve host in vivo. P. chabaudi pRBCs were exposed for 1 h at 37 °C to varying concentrations of CysH, which was subsequently washed off. The equivalent of 1 × 105 pRBCs (calculated prior to drug exposure) was then injected into mice without any additional exposure to CysH in vivo, and parasite replication was measured (Fig. 2). CysH treatment of the inoculum resulted in a dose-dependent delay in appearance of parasitemia (Fig. 2A), and a dose-dependent reduction in parasitemia at day 8 ranging from 25% to 85% inhibition (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that a single 1 h exposure of P. chabaudi parasites to CysH is sufficient to significantly reduce parasite viability. Importantly, this anti-parasitic effect is detectable ex vivo, in the absence of the host immune system, and is in agreement with the hypothesis that CysH has a direct anti-parasitic effect.

Fig. 2.

The effect of cysteamine treatment ex vivo on infectivity of P. chabaudi. P. chabaudi parasitized erythrocytes (pRBCs) were incubated with CysH for 1 h at 37 °C, ex vivo. Subsequently, mice were infected i.v. with each of the treated suspensions (1 × 105 pRBC) and parasitemia was monitored (A); error bars represent SEM. The inhibitory effect of CysH treatment on development of parasitemia at day 8 is shown for individual animals (% parasitemia) and is calculated as a fraction of the untreated group (% inhibition) in (B).

3.4. Specificity of the cysteamine anti-parasitic effect

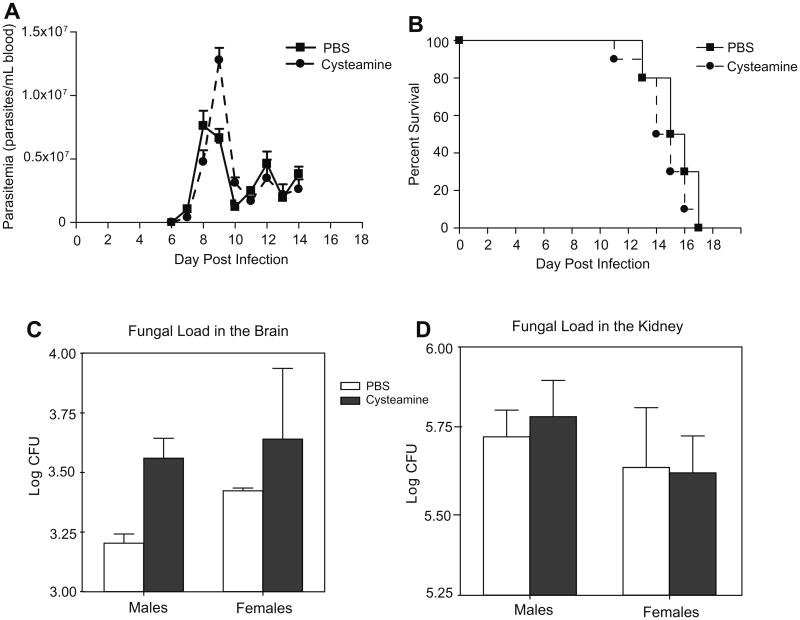

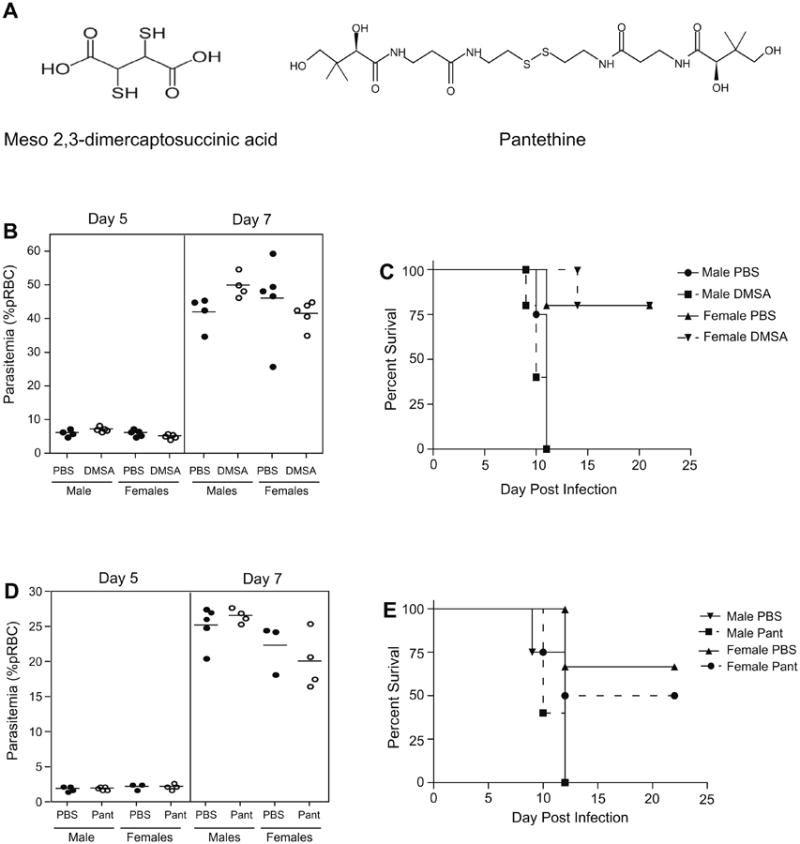

We next investigated whether CysH could prove generally beneficial against other infections, namely the blood parasite T. cruzi and the fungal pathogen C. albicans. For both pathogens, a robust host pro-inflammatory response is absolutely required to control systemic infection; hence, a non-specific effect of cysteamine on host inflammatory response may influence pathogenesis and/or outcomes of infection with these pathogens (Michailowsky et al., 2001; Romani, 1999). A/J mice are susceptible to both infections (Trischmann and Bloom, 1982; Tuite et al., 2004) and were therefore chosen for these experiments. Using a prophylactic regimen (daily i.p. injections at 120 mg/kg or 150 mg/kg) (Fig. 3), CysH treatment had no protective effect on either extent of blood-stage replication of T. cruzi (A) or overall survival from infection (B). Likewise, CysH treatment was not protective against C. albicans; 24 h post-infection, fungal loads measured in brain and kidney were similar in treated vs. control groups (C/D). In agreement with Fig. 2, these results argue against a non-specific effect of CysH on up-regulation of host inflammatory response, but rather support a Plasmodium specific anti-parasitic activity of CysH. We also tested potential anti-malarial activity of compounds structurally and functionally related to CysH. DMSA [meso 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid; HO2CCH(SH)CH(SH)CO2H], is a small bisthiol (Fig. 4A) clinically used in chelation therapy (Aposhian, 1983). DMSA treatment (prophylactic treatment at equimolar doses) had no effect on blood parasitemia (at days 5 and 7) or survival in P. chabaudi-infected mice (Fig. 4B and C). We also tested pantethine, a dimer of pantetheine (Fig. 4A) that has recently been reported to improve survival from cerebral malaria in mice infected with P. berghei ANKA, although no effect on parasitemia was reported (Penet et al., 2008). Pantethine treatment (prophylactic treatment at equimolar doses) did not have a major effect on either blood parasitemia or survival of P. chabaudi-infected mice (Fig. 4D and E). These results strongly suggest structural specificity of CysH in its anti-parasitic activity that is not limited to a free thiol and is lost when the cysteamine moiety is included in the molecular backbone of pantethine.

Fig. 3.

Cysteamine treatment in mouse models of T. cruzi and C. albicans infections. A/J mice were infected intra-peritoneally with Trypanosoma cruzi (103 trypomastigotes; Y strain), treated with CysH (dashed line) or PBS alone (solid line) and the number parasites in the blood was monitored daily. CysH was given daily by intra-peritoneal injection (150 mg/kg) starting 2 days prior to infection and continuing up to day 14. The kinetics of the infection are shown in (A), expressed as parasites/mL of blood, and the survival of CysH or PBS-treated mice is shown in a Kaplan–Meier plot (B). A/J mice were infected intravenously with Candida albicans (3 × 105 blastospores; SC5134) and 24 h later the animals were sacrificed and total organ fungal loads were determined in brain (C) and kidney (D). Animals were treated daily (solid bars) or not (empty bars; PBS treated) with CysH (120 mg/kg) starting 2 days prior to infection and ending at 24 h post-infection.

Fig. 4.

The effect of DMSA and pantethine on P. chabaudi infection in vivo. The effect of thiol-based compounds DMSA (meso 2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid) and pantethine was examined in susceptible A/J mice. The structure of each compound is shown in (A). Male and female mice were treated daily with 50 mg/kg of DMSA or 30 mg per mouse of pantethine, using a prophylactic regimen (staring 2 days prior to infection and continuing every day thereafter until day 12). Parasitemia, expressed as percent parasitized erythrocytes, is plotted at day 5 and day 7 post-infection for DMSA (B) and pantethine (D) with each dot representing a mouse. Filled circles are untreated (PBS) and empty circles are treated animals. Survival is shown as a Kaplan–Meier plot for DMSA (C) and pantethine (E) treated (dashed line) and control (solid line) groups.

3.5. Cysteamine reduces viability of P. falciparum in vitro

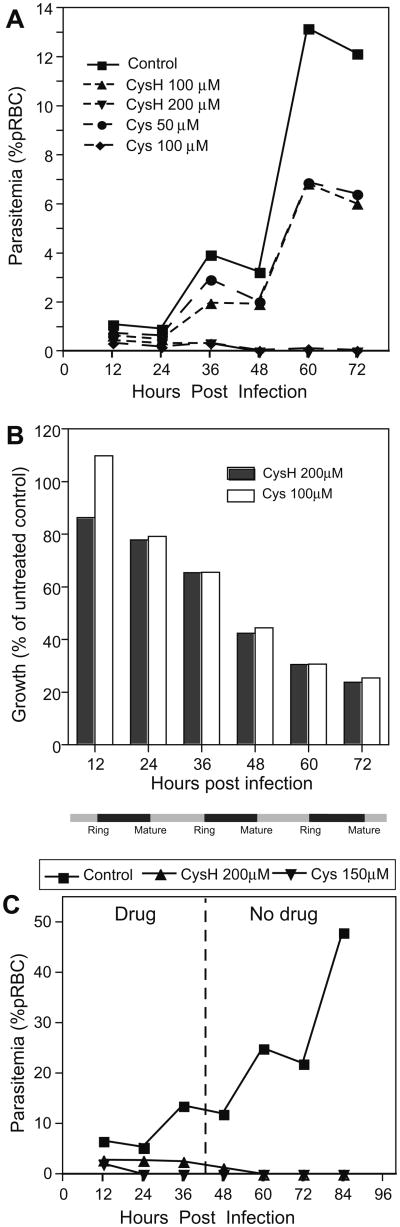

We next monitored the effect of Cys and CysH on the replication of P. falciparum in human RBCs in vitro, during a 6-day period (equivalent to three cycles of invasion and maturation). Parasite replication was monitored by enumeration of intracellular parasites from stained smears (expressed as % parasitemia) (Fig. 5A), by a fluorescence-based method to quantify P. falciparum-derived DNA (Fig. 5B), and by measuring parasite-specific lactate dehydrogenase activity (data not shown). CysH (200 μM) and Cys (100 μM) could completely inhibit replication of the chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum ITG isolate starting at the second cycle of invasion/maturation, while 50 μM Cys or 100 μM CysH also inhibit parasitemia (Fig. 5A). Similar inhibition of growth was seen using P. falciparum 3D7, a chloroquine-sensitive isolate (data not shown). This growth inhibition of P. falciparum was validated using SYBR- green, where we detected growth inhibition as early as day 2 and continuing through the 2nd and 3rd cycles of invasion and maturation (d3–d6) with an optimal 70% inhibition at day 6 (Fig. 5B). IC50 values (ITG isolate) were calculated to be 93 μM and 40 μM for CysH and Cys, respectively. In another experiment, P. falciparum (ITG) pRBCs were treated or not for 3 days with Cys (150 μM) or CysH (200 μM), the compounds were removed by washing and parasite growth was monitored for an additional 4 days in drug-free medium (Fig. 5C). Treated cultures showed a complete absence of replication, while there was progressive replication of the control parasite culture. This suggests that exposure to Cys or CysH at the concentrations tested cause irreversible damage to the P. falciparum parasites that abrogates their ability to further replicate in RBCs. These results show that CysH and the Cys dimer can inhibit growth of chloroquine-resistant isolates of P. falciparum in human erythrocytes in vitro.

Fig. 5.

Growth inhibition of P. falciparum by cysteamine and cystamine in vitro. Growth of P. falciparum in human RBCs treated with CysH or Cys was monitored and is expressed as percentage of pRBC for a chloroquine-resistant isolate (ITG; A). The line graph represents the growth of treated and untreated cultures over three cycles of invasion and growth (indicated by grey and black bars, resp. along the bottom). Parasite growth was measured by SYBR-green analysis of Plasmodium DNA during treatment (B) and is expressed as a percentage of the untreated control at each time point. In (C), P. falciparum ITG cultures were treated for 3 days (d1–d3) with CysH (200 μM) or Cys (150 μM). CysH/Cys treatment was stopped at day 4 and the culture was continued for 4 days (d4–d7) with daily medium replacement without addition of compound. Line graphs represent parasitemia levels of treated and untreated cultures and the dashed line represents the removal of drug.

To ensure that the anti-parasitic mechanism of action of Cys and CysH is specific and not linked to non-specific but detrimental effects on erythrocytes, we measured the effect of treatment on markers of erythrocyte integrity, namely the levels of intracellular ATP and glutathione (GSH) in uninfected cells (Figure S2). There was no effect of either Cys or CysH on intracellular ATP levels, while both compounds slightly increased the GSH levels at 24 h after treatment; this argues against a major effect of CysH on uninfected erythrocyte metabolism.

3.6. Effect of cysteamine and/or chloroquine exposure on human hemoglobin degradation by the Plasmodium parasite

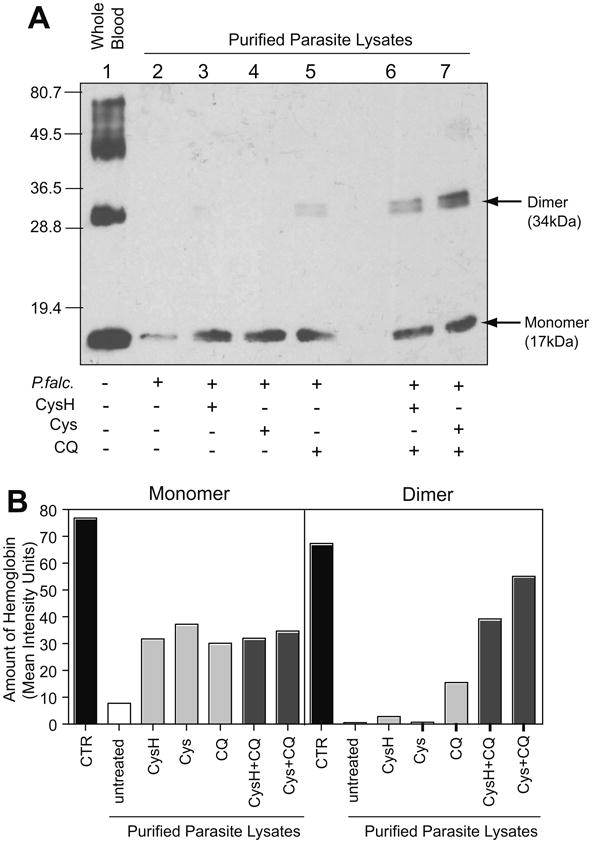

To begin to investigate possible mechanisms of action, we monitored the effect of CysH treatment, alone and with chloroquine, on parasite-mediated intracellular degradation of hemoglobin (Hb), the main nutrient source for intracellular Plasmodium and the target of some known anti-malarials (Francis et al., 1997). Human RBCs were infected with P. falciparum and then exposed (18 h) to concentrations of CysH, Cys, or chloroquine that are known to block parasite replication (Fig. 5), or combinations of the drugs. Lysates from intracellular parasites were prepared, and tested for presence of Hb by immunoblotting (Fig. 6). Panel A shows a representative blot and Panel B presents the quantification of this blot. An equivalent amount of whole uninfected RBC proteins was used as control to identify monomeric and multimeric forms of Hb (lane 1 in Fig. 6A; black bars in Fig. 6B); these are largely absent from parasite lysates prepared from infected but untreated RBCs (lane 2 in A; white bars in B). As previously reported (Hoppe et al., 2004), treatment of pRBCs with the anti-malarial drug chloroquine (lane 5) caused a significant increase in the amount of parasite-associated intact Hb. Likewise, treatment of pRBCs with either CysH or Cys (lane 3, lane 4 in A; light grey bars in B) caused an increase in parasite-associated intact Hb, suggesting that both compounds can block intracellular, parasite-mediated Hb degradation. Exposure of pRBCs to combinations of chloroquine, and either CysH and Cys (lanes 6 and 7; dark grey bars in B) caused a further increase in inhibition of Hb degradation, as evidenced by abundance of the Hb dimers detected under these conditions, and suggesting potential additive effects of the two compounds.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of hemoglobin degradation by cysteamine and cystamine. Purified P. falciparum lysates from cultures treated or not with CysH (150 μM), Cys (75 μM), chloroquine (20 nM) or in combination, were assayed for Hb levels by immunoblotting (A). Uninfected whole blood lysate is shown in lane 1. Untreated parasite lysate is shown in lane 2, while treated lysates are present in lane 3–7. Twenty micrograms of total protein was loaded in each lane and the molecular mass markers are indicated in kilodaltons. A histogram plot (B) represents the quantification of the immunoblot in (A) showing the mean intensity units for the band after background subtraction. Abbreviations: CQ, chloroquine; CTR, whole blood control lysate.

Taken together, results obtained in our in vivo mouse model of infection with P. chabaudi and in vitro studies with P. falciparum reveal specific anti-parasitic activity of the physiological aminothiol cysteamine and its dimer, cystamine.

4. Discussion

What is the mechanistic basis of the anti-parasitic effect of CysH? Vnn1−/− mice that lack tissue-specific pantetheinase-driven CysH production in the intestine are protected against pathological effects of acute inflammation caused by either infection with the nematode S. mansoni, or by treatment with high doses of the anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin (Martin et al., 2004). The protective effect was associated with decreased infiltration at the site of the lesions and reduced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Importantly, the protective effect could be reversed by passive administration of Cys (Martin et al., 2004; Berruyer et al., 2004). In addition, Vnn1−/− mice have decreased inflammatory response during infection with Coxiella burnetii (Meghari et al., 2007). Vnn1 may also regulate PPARγ in epithelial cells, thereby modulating inflammation in an intestinal model of colitis (Berruyer et al., 2006). Together, these results have suggested a pro-inflammatory function for CysH in host defense against certain infections in the intestine, providing a plausible hypothesis for the anti-malarial effect, i.e. the effect on ultimate survival. However, the specificity of the CysH effect detected in our in vivo experiments, the absence of stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production in infected CysH-treated animals, and the direct effect of CysH on P. chabaudi ex vivo and P. falciparum in vitro strongly argue against a mechanism based on enhanced host inflammatory response.

The effect of cysteamine on parasitemia in vivo does not completely eliminate parasites; however, the presence of cysteamine in the plasma is transient and cysteamine administered to tissue homogenates disappears rapidly (Pinto et al., 2005), and is metabolized quickly to taurine. This suggests that parasitized red cells are not exposed to cysteamine for long periods of time in vivo and may explain the discrepancies between the effect seen in vivo (Fig. 1) versus the effect on P. chabaudi ex vivo (Fig. 2). This data suggests that alternate routes of administration or formulations may increase the exposure time or level in vivo and thereby may have greater impact on parasite burdens. Nevertheless, our results show that even modest inhibition of parasite levels by cysteamine, either prophylactically or therapeutically administered, have a significant impact on overall outcome of the infection, as measured by survival (Fig. 1). The reduction in parasitemia after treatment allowed the mice to mount a sufficient response to eventually sterilize the infection. Pharmacokinetic studies have revealed that cysteamine doses used in this model, although high, result in plasma levels similar to those observed in humans taking cysteamine (Cystagon™) for the treatment of nephropathic cystinosis. For example, 50 mg/kg cysteamine given sub-cutaneously (s.c.) (data not shown) has a similar pharmacokinetic profile to one 500 mg tablet of cysteamine bitartrate taken orally (Belldina et al., 2003), and three consecutive s.c. doses of 50 mg/kg generate an anti-malarial effect in mice equivalent to 120 mg/kg injected i.p. (data not shown). Therefore, the cysteamine dosing protocol used in this model and showing efficacy is also pharmacologically relevant.

As a potent anti-oxidant, CysH may directly or indirectly (through modulation of glutathione (GSH) stores) cause changes in cellular redox potential, either in situ or systemically, perhaps negatively impacting intracellular replication of Plasmodium. Relevant to this argument, CysH administration in vivo causes a decrease in liver GSH stores (Martin et al., 2004; Griffith et al., 1977), and inhibition of glutathione reductase causes a reduction in intracellular GSH levels, which has been associated with a plasmocidal effect (Luersen et al., 2000). Likewise, buthionin sulfoximine (BSO), a GSH scavenger and inhibitor of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γGCS), shows anti-Plasmodium activity (Luersen et al., 2000) and can ameliorate the pathogenesis of Trypanosoma brucei infection in mice (Arrick et al., 1981). Therefore, CysH-mediated modulation of GSH levels in the host, either systemically or in situ in RBCs, or in the parasite itself may contribute to the anti-malarial effect of the compound. However, the inability of CysH to modify the course of Trypanosoma infection in mice (Fig. 3) suggests that GSH scavenging may not be the mechanism of action of CysH, in the manner that has been shown for BSO against T. brucei (Arrick et al., 1981). Our data supports a model in which CysH has a direct cytostatic or cytocidal effect on the parasite. Such a mechanism may be through alteration of the parasite redox potential or through binding/modification of essential parasite proteins via its reactive sulfhydril group.

CysH is the current therapy for children with nephropathic cystinosis. Cystinosis is caused by mutations in the cystine lysosomal transporter Cystinosin (Anikster et al., 1999). In acidic lysosomes, cysteine produced by protein degradation is oxidized to cystine, which is poorly soluble. Normally, both cysteine and cystine can be exported into the cytoplasm by the cystinosin carrier, a process that is impaired in cystinosis patients, leading to precipitation of cystine crystals and ensuing cellular and organ damage (Kalatzis and Antignac, 2003). CysH acts by undergoing disulphide exchange with lysosomal cystine to form the cysteine–CysH mixed disulphide structurally similar to lysine, which is then effluxed by the lysine transporter (Gahl et al., 1985). Similarly, CysH may enter and accumulate in the acidic food vacuole of the parasite. At that site, it may compromise parasite viability by interfering with either normal amino acid metabolism or transport into the cytoplasm, or by inhibiting the activity of certain enzymes essential for the activity of this organelle. Plasmodium cysteine proteases, such as the falcipains, are known to have critical roles in hemoglobin hydrolysis, releasing amino acids for protein synthesis (Rosenthal, 2004). Inhibition of these cysteine proteases results in swelling of the food vacuole with un-degraded hemoglobin (Rosenthal et al., 1988). Our results in Fig. 6 suggest that CysH or Cys may interfere with the ability of the parasite to efficiently metabolize host hemoglobin. Whether this is due to inhibition of parasite proteases or hemozoin formation, the postulated target of chloroquine (Fitch, 2004; Sullivan et al., 1996), or other unidentified mechanisms, remains to be demonstrated.

In conclusion, our studies have identified cysteamine, the natural product of the pantetheinase reaction as exhibiting activity against Plasmodium replication in vitro (P. falciparum) and in vivo (P. chabaudi), thereby also improving outcome in otherwise susceptible animals. Importantly, CysH is produced endogenously and therefore represents a novel host-derived and specific, anti-parasitic agent. The elucidation of the mechanism of action of cysteamine against Plasmodium parasites will shed light on general host-protective mechanisms in malaria, which could lead to innovative, targeted therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CIHR Team Grant in Malaria(K.C.K., P.G., M.M.S.), operating grant MOP-79343 and POP2 (P.G.), MT-13721 (K.C.K.), Genome Canada through the Ontario Genomics Institute (K.C.K.), CIHR Canada Research Chair (K.C.K.).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2010.02.009.

References

- Aitman TJ, Cooper LD, Norsworthy PJ, Wahid FN, Gray JK, Curtis BR, McKeigue PM, Kwiatkowski D, Greenwood BM, Snow RW, Hill AV, Scott J. Malaria susceptibility and CD36 mutation. Nature. 2000;405:1015–1016. doi: 10.1038/35016636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anikster Y, Shotelersuk V, Gahl WA. CTNS mutations in patients with cystinosis. Human Mutation. 1999;14:454–458. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(199912)14:6<454::AID-HUMU2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aposhian HV. DMSA and DMPS–water soluble antidotes for heavy metal poisoning. Annual Reviews of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 1983;23:193–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.23.040183.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrick BA, Griffith OW, Cerami A. Inhibition of glutathione synthesis as a chemotherapeutic strategy for trypanosomiasis. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1981;153:720–725. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.3.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayi K, Min-Oo G, Serghides L, Crockett M, Kirby-Allen M, Quirt I, Gros P, Kain KC. Pyruvate kinase deficiency and malaria. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:1805–1810. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayi K, Turrini F, Piga A, Arese P. Enhanced phagocytosis of ring-parasitized mutant erythrocytes: a common mechanism that may explain protection against falciparum malaria in sickle trait and beta-thalassemia trait. Blood. 2004;104:3364–3371. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belldina EB, Huang MY, Schneider JA, Brundage RC, Tracy TS. Steady-state pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cysteamine bitartrate in paediatric nephropathic cystinosis patients. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2003;56:520–525. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berruyer C, Martin FM, Castellano R, Macone A, Malergue F, Garrido-Urbani S, Millet V, Imbert J, Dupre S, Pitari G, Naquet P, Galland F. Vanin-1−/− mice exhibit a glutathione-mediated tissue resistance to oxidative stress. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24:7214–7224. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.16.7214-7224.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berruyer C, Pouyet L, Millet V, Martin FM, LeGoffic A, Canonici A, Garcia S, Bagnis C, Naquet P, Galland F. Vanin-1 licenses inflammatory mediator production by gut epithelial cells and controls colitis by antagonizing peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activity. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203:2817–2827. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler E. Red Cell Metabolism: A Manual of Biochemical Methods. Grune & Stratton; Orlando: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brener Z. Therapeutic activity and criterion of cure on mice experimentally infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de Sao Paulo. 1962;4:389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogdon WG, McAllister JC. Insecticide resistance and vector control. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 1998;4:605–613. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djurhuus R, Svardal AM, Ueland PM. Cysteamine increases homocysteine export and glutathione content by independent mechanisms in C3H/10T1/2 cells. Molecular Pharmacology. 1990;38:327–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp AM, Nosten F, Yi P, Das D, Phyo AP, Tarning J, Lwin KM, Ariey F, Hanpithakpong W, Lee SJ, Ringwald P, Silamut K, Imwong M, Chotivanich K, Lim P, Herdman T, An SS, Yeung S, Singhasivanon P, Day NP, Lindegardh N, Socheat D, White NJ. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre S, Graziani M, Rosei M, Fabi A, Del Grosso E. The enzymatic breakdown of pantethine to pantothenic acid and cystamine. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1970;16:571–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch CD. Ferriprotoporphyrin IX, phospholipids, and the antimalarial actions of quinoline drugs. Life Sciences. 2004;74:1957–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin A, Cardon LR, Tam M, Skamene E, Stevenson MM, Gros P. Identification of a new malaria susceptibility locus (Char4) in recombinant congenic strains of mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:10793–10798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191288998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin A, Stevenson MM, Gros P. Complex genetic control of susceptibility to malaria in mice. Genes and Immunity. 2002a;3:177–186. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin A, Stevenson MM, Gros P. Susceptibility to malaria as a complex trait: big pressure from a tiny creature. Human Molecular Genetics. 2002b;11:2469–2478. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.20.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SE, Sullivan DJ, Jr, Goldberg DE. Hemoglobin metabolism in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Annual Reviews of Microbiology. 1997;51:97–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahl WA. Early oral cysteamine therapy for nephropathic cystinosis. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2003;162(Suppl. 1):S38–S41. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1349-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahl WA, Tietze F, Butler JD, Schulman JD. Cysteamine depletes cystinotic leucocyte granular fractions of cystine by the mechanism of disulphide interchange. Biochemical Journal. 1985;228:545–550. doi: 10.1042/bj2280545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith OW, Larsson A, Meister A. Inhibition of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase by cystamine: an approach to a therapy of 5-oxoprolinuria (pyroglutamic aciduria) Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1977;79:919–925. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)91198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Valladares M, Naessens J, Iraqi FA. Genetic resistance to malaria in mouse models. Trends in Parasitology. 2005;21:352–355. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe HC, van Schalkwyk DA, Wiehart UI, Meredith SA, Egan J, Weber BW. Antimalarial quinolines and artemisinin inhibit endocytosis in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48:2370–2378. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2370-2378.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JE. Drug-resistant malaria—an insight. FEBS Journal. 2007;274:4688–4698. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon JH, Lee HJ, Jang GY, Kim CW, Shim DM, Cho SY, Yeo EJ, Park SC, Kim IG. Different inhibition characteristics of intracellular transglutaminase activity by cystamine and cysteamine. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2004;36:576–581. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalatzis V, Antignac C. New aspects of the pathogenesis of cystinosis. Pediatric Nephrology. 2003;18:207–215. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalatzis V, Cherqui S, Antignac C, Gasnier B. Cystinosin, the protein defective in cystinosis, is a H(+)-driven lysosomal cystine transporter. EMBO Journal. 2001;20:5940–5949. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DP. How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach us about malaria. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2005;77:171–192. doi: 10.1086/432519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luersen K, Walter RD, Muller S. Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells depend on a functional glutathione de novo synthesis attributable to an enhanced loss of glutathione. Biochemical Journal. 2000;346(Pt. 2):545–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier AG, Duraisingh MT, Reeder JC, Patel SS, Kazura JW, Zimmerman PA, Cowman AF. Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion through glycophorin C and selection for Gerbich negativity in human populations. Nature Medicine. 2003;9:87–92. doi: 10.1038/nm807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Malergue F, Pitari G, Philippe JM, Philips S, Chabret C, Granjeaud S, Mattei MG, Mungall AJ, Naquet P, Galland F. Vanin genes are clustered (human 6q22–24 and mouse 10A2B1) and encode isoforms of pantetheinase ectoenzymes. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:296–306. doi: 10.1007/s002510100327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Penet MF, Malergue F, Lepidi H, Dessein A, Galland F, de Reggi M, Naquet P, Gharib B. Vanin-1(−/−) mice show decreased NSAID- and Schistosoma-induced intestinal inflammation associated with higher glutathione stores. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113:591–597. doi: 10.1172/JCI19557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meghari S, Berruyer C, Lepidi H, Galland F, Naquet P, Mege JL. Vanin-1 controls granuloma formation and macrophage polarization in Coxiella burnetii infection. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37:24–32. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michailowsky V, Silva NM, Rocha CD, Vieira LQ, Lannes-Vieira J, Gazzinelli RT. Pivotal role of interleukin-12 and interferon-gamma axis in controlling tissue parasitism and inflammation in the heart and central nervous system during Trypanosoma cruzi infection. American Journal of Pathology. 2001;159:1723–1733. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LH, Mason SJ, Clyde DF, McGinniss MH. The resistance factor to Plasmodium vivax in blacks. The Duffy-blood-group genotype, FyFy. New England Journal of Medicine. 1976;295:302–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608052950602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min-Oo G, Fortin A, Pitari G, Tam M, Stevenson MM, Gros P. Complex genetic control of susceptibility to malaria: positional cloning of the Char9 locus. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204:511–524. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min-Oo G, Fortin A, Tam MF, Gros P, Stevenson MM. Phenotypic expression of pyruvate kinase deficiency and protection against malaria in a mouse model. Genes and Immunity. 2004;5:168–175. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min-Oo G, Fortin A, Tam MF, Nantel A, Stevenson MM, Gros P. Pyruvate kinase deficiency in mice protects against malaria. Nature Genetics. 2003;35:357–362. doi: 10.1038/ng1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy VS, Good MF, Hill AV. Malaria vaccine developments. The Lancet. 2004;363:150–156. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15267-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penet MF, Abou-Hamdan M, Coltel N, Cornille E, Grau GE, de Reggi M, Gharib B. Protection against cerebral malaria by the low-molecular-weight thiol pantethine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:1321–1326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706867105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto JT, Van Raamsdonk JM, Leavitt BR, Hayden MR, Jeitner TM, Thaler HT, Krasnikov BF, Cooper AJ. Treatment of YAC128 mice and their wild-type littermates with cystamine does not lead to its accumulation in plasma or brain: implications for the treatment of Huntington disease. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;94:1087–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani L. Immunity to Candida albicans: Th1, Th2 cells and beyond. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 1999;2:363–367. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal PJ. Cysteine proteases of malaria parasites. International Journal for Parasitology. 2004;34:1489–1499. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal PJ, McKerrow JH, Aikawa M, Nagasawa H, Leech JH. A malarial cysteine proteinase is necessary for hemoglobin degradation by Plasmodium falciparum. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1988;82:1560–1566. doi: 10.1172/JCI113766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smilkstein M, Sriwilaijaroen N, Kelly JX, Wilairat P, Riscoe M. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48:1803–1806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1803-1806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan DJ, Jr, Gluzman IY, Russell DG, Goldberg DE. On the molecular mechanism of chloroquine's antimalarial action. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:11865–11870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trischmann TM, Bloom BR. Genetics of murine resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi. Infection and Immunity. 1982;35:546–551. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.2.546-551.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuite A, Mullick A, Gros P. Genetic analysis of innate immunity in resistance to Candida albicans. Genes and Immunity. 2004;5:576–587. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. Genetic variability in response to infection: malaria and after. Genes and Immunity. 2002;3:331–337. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PL, Khan MA, Moskal JR. Cellular thiol pools are responsible for sequestration of cytotoxic reactive aldehydes: central role of free cysteine and cysteamine. Brain Research. 2007;1158:158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.