Abstract

A 3D microvascularized gelatin hydrogel is produced using thermoresponsive sacrificial poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) microfibers. The capillary-like microvascular network allows constant perfusion of media throughout the thick hydrogel, and signifcantly improves the viability of human neonatal dermal fibroblasts encapsulated within the gel at a high density.

Keywords: tissue engineering, artificial vasculature, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide), gelatin hydrogel, microfibers

Tissue engineering is an exciting approach to regenerate or replace damaged host tissue using an artificial tissue construct consisting of an appropriate combination of cells, scaffolds, and biochemicals.[1, 2] Among the various scaffolds of interest, hydrogels are among the most attractive due to their tunable physical and biochemical properties that can mimic the natural extracellular matrix (ECM).[3-5] However, a major challenge in scaling cell-laden hydrogel scaffolds for therapeutic applications remains the inability to maintain a high density of metabolically active cells throughout a tissue-scale construct. Diffusion alone cannot provide sufficient exchange of soluble compounds (e.g. oxygen, nutrients, waste products) for cells further than a few hundred microns from a media source. Thus, engineering a 3D artificial vasculature that enables active perfusion of thick hydrogel scaffolds is essential. In this work, we present a top-down fabrication approach yielding capillary-like 3D microfluidic networks in gelatin hydrogels and demonstrate that perfusion of such networks dramatically enhances the viability of embedded cells. By appropriately choosing the sacrificial material and utilizing a non-traditional microfiber-based fabrication approach, we are able to form channels with diameters and densities that have yet to be demonstrated by other “top-down” techniques. The excellent cytocompatibility and simplicity of this scheme promises to enable future efforts towards engineering thick prevascularized tissue constructs.

Vessel networks within engineered tissue constructs can be formed by either “bottom-up” or “top-down” approaches. In a typical “bottom-up” approach, endothelial cells or progenitor cells are cultured within an appropriate environment and allowed to spontaneously form lumen networks.[6-10] This strategy has several advantages, including simplicity, and the fact that the vessel network architecture is formed via a physiological process and thus likely to mimic in vivo phenomena. There are, however, some limitations to this approach. In previous studies, the formation of a perfusable lumen network can take weeks, and thus if this approach were used to form thick tissue, interior cells would not have immediate access to the soluble compound exchange required for survival.

Alternatively, constructs with channels fabricated using a “top-down” approach [11-16] benefit from a perfusable channel network that is immediately available to supply all embedded cells. A number of strategies including extrusion-molding,[17] template stamping,[18-20] soft lithography,[20-23] and 3D bioprinting.[24-28] of hydrogels have been developed to create vascular networks within such constructs. Early efforts in this area employed lithographic techniques to produce 2D patterns of channels within hydrogels.[20, 22, 29] More recently, researchers have focused on using 3D printing techniques to form microfluidic networks with complexity in the third dimension. Previous top-down strategies to create networks of large diameter (> 100µm) channels in hydrogel scaffolds have used water-soluble materials such as sugar (cotton candy),[30] carbohydrate glass,[14] Pluronic F127,[31] gelatin,[29] and PVA[32]. The difficulty of these techniques, however, stems from the conflicting requirements of a template that is water-insouble during the embedding process, but water-soluble after the gel has set. Previously, we demonstrated the ability to generate microchannels in gelatin using a sacrificial shellac template with triggerable dissolution that depends on pH.[33] Similarly, Kolesky et al recently reported using a 3D printed sacrificial template in the presence of a cell-laden hydrogel by exploiting the thermoresponsive behavior of Pluronic F127. However, removing Pluronic F127 requires cooling the scaffold to 4 ºC, which potentially damages encapsulated cells.[15, 34]

In this study, we report a sacrificial template-based strategy using solvent-spun poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) fibers to produce 3D microvascular networks in cell-laden gelatin hydrogels with negligible cytotoxicity (Figure 1A). PNIPAM was chosen as the sacrificial material because of its attractive thermoresponsive behavior (lower critical solution temperature [LCST] near 32 ºC) and previous reports of excellent cytocompatibility. [35-39] We exploited the temperature-dependent solubility of PNIPAM to allow an aqueous fabrication process, avoiding use of organic solvents or extreme temperatures for removal, thus providing a safe culture environment for cells loaded into the hydrogel. The resulting channels facilitate effective perfusion of culture media throughout the scaffold volume and enhances the viability of embedded cells.

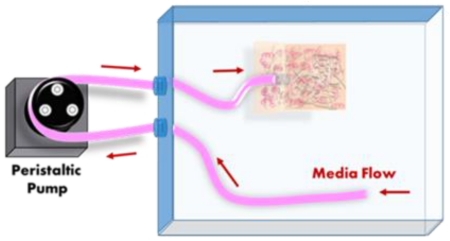

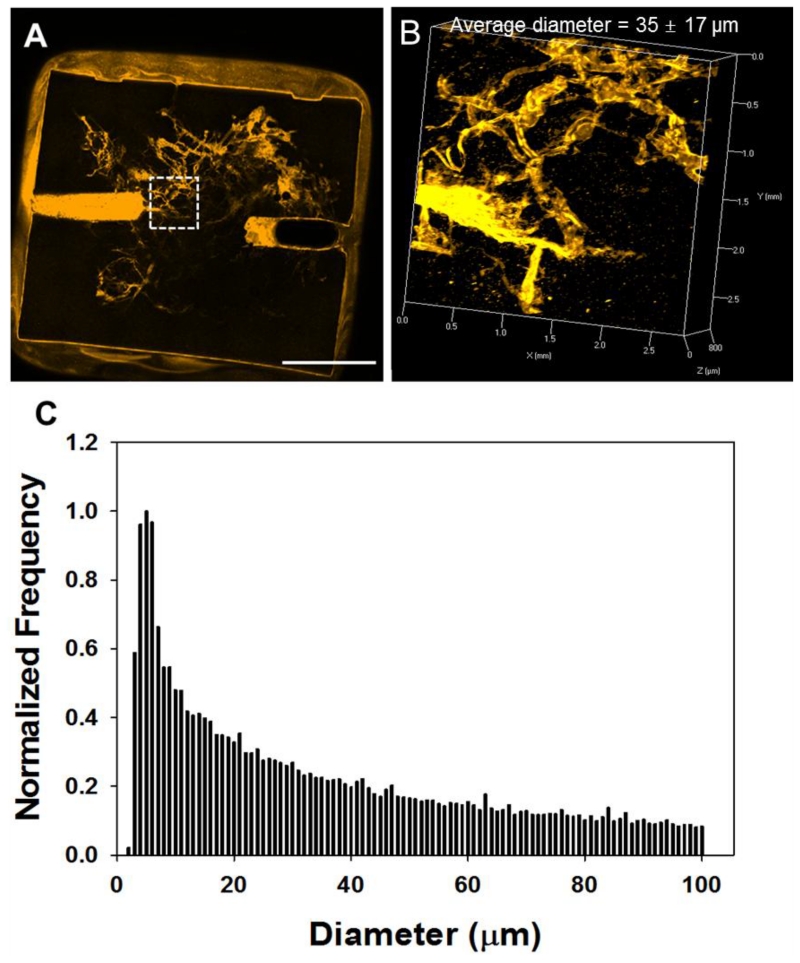

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the perfusion system (A); and a SEM image (B) and diameter distribution (C) of PNIPAM microfibers.

High speed spinning of PNIPAM solution at room temperature (Figure S1A) yielded microfibers with smooth surfaces and diameters ranging from 3 to 55 µm (Figure 1B and 1C). To provide an interfacing macrochannel for interfacing with an external pump, PNIPAM rods were prepared by heating and solidifying PNIPAM solution in 1.3 mm inner diameter silicone tubing. Assembly of the microfluidic hydrogels is achieved by embedding microfibers (at roughly 0.1%-0.3% of the construct volume) within an enzyme (microbial transglutaminase: mTGase) -mediated crosslinkable gelatin hydrogel with macrochannels serving as inlet and outlet conduits for the perfusion setup (Figure 1A and S1B). During the gelation process, the key to maintaining the integrity of the PNIPAM fiber structure was to minimize the exposure of the device to a temperature below 32 ºC. The gelatin/mTGase/cell solution was kept at 37 ºC both prior to embedding the PNIPAM template and during the gelation process. Upon complete gelation, the PNIPAM structure was removed by immersing the entire construct in cell culture media at room temperature.

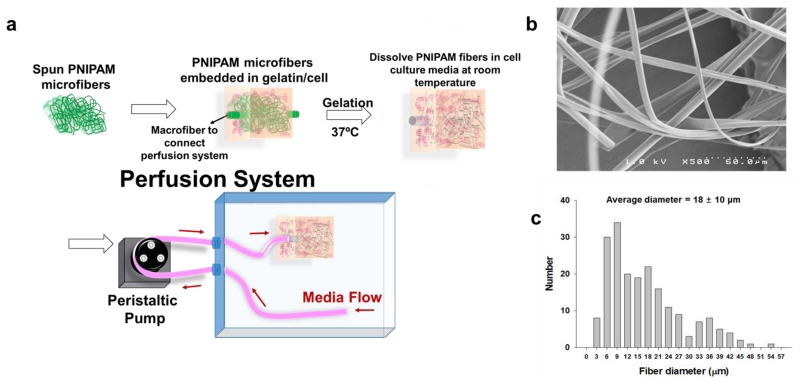

To analyze channel architecture and interconnectivity, FluoSpheres (0.2 μm, orange) were introduced into the macrochannel, and thus only the microchannels connected to the macrochannel were perfused and fluorescent (Figures 2A and 2B). As all the microchannels appeared to be perfused (empty channels would also be visible and appear as darker regions due to the gelatin autofluorescence), it was assumed that the macrochannels were successfully interconnected and formed perfusable networks. To characterize the microchannel size distribution, we obtained 3D images of the orange FluoSphere-filled constructs using confocal microscopy (Figure 2B). As has been described previously, the 3D channel dataset was skeletonized and the distances from the resulting channel centerlines to the channel wall were measured.[33] Overall, the channels had a mean diameter of 35 μm and standard deviation of 16 μm as summarized in Figure 2C. While similar data from morphometric studies of natural vessel networks is often binned much more coarsely over a much larger diameter range (typically categorizing vessels by “order” using a variety of techniques,[40] our distribution is not too dissimilar from small vessel data obtained by morphometric studies of pig vasculature by Kassab et al.[41] We also observed that, in freshly fabricated fibers, 19% measured less than 6 μm in diameter, whereas the portion of channels with diameters less than 6 μm was 10% in the gelatin hydrogel. This observed shift in the diameter distribution towards larger diameters is likely due to PNIPAM swelling in the gelatin solution, as well as aggregation of fibers. Additionally, when channels (including macrochannels) were introduced, the macroscopic hydrogel stiffness decreased (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

2D (A) and 3D (B) confocal microscope images of the gelatin hydrogel with microchannels, and channel diameter distribution (C). Scale bar = 5 mm.

To demonstrate the utility of these 3D capillary-like microfluidic networks in maintaining cell viability throughout thick hydrogel constructs, we compared the number of live fibroblasts encapsulated in microfluidic gelatin hydrogels with and without media perfusion, as well as in a solid, channel-less control. Through preliminary screening, 8% w/v gelatin with 2% w/v enzyme was determined to be an optimal composition for maintaining cell viability and the structural integrity of the capillary network within the hydrogel (data not shown).

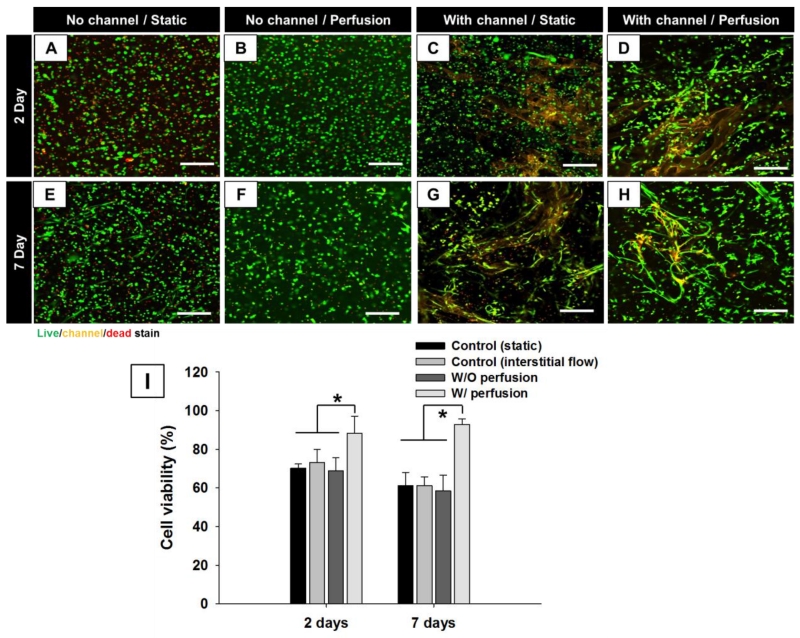

For scaffolds (both with and without channels) incubated under static conditions, a greater quantity of dead cells was observed compared to perfused hydrogels, indicating a need of perfusable channel networks to improve mass transport into the scaffold core (Figure S3 and S4). In particular, we observed that cells at the construct periphery survived whereas cells deeper within the construct did not, illustrating the diffusion limitations that must be overcome for thick tissue engineering. Hydrogels with microchannels and perfusion showed over 96% cell viability on days 2 and 7, whereas non-perfused hydrogels showed only 60% cell viability, as did control hydrogels (without channels) subjected to interstitial flow (Figure 3I). The presence of perfusion or microchannels alone did not improve cell survival because the diffusion of media through the microchannels under such conditions did not provide sufficient nutrient exchange. These results reflect that hydrogel perfusion at 150 μl/min, chosen initially based upon previous experiments clearly promote long-term cell viability.[42] Optimization of perfusion rate to meet the specific metabolic needs of fibroblasts may further increase cell viabilty and function.

Figure 3.

Human neonatal dermal fibroblasts in gelatin hydrogels w/o channel or perfusion (A, E), w/o channel and with interstitial flow (B, F), w/ channel w/o perfusion (C, G), and w/ channel and perfusion (D, H) after two (A, B, C, D) and seven (E, F, G, H) days of culture were stained with a fluorescent live/dead assay (green for live cells by Calcein AM; red for dead cells by Sytox blue) and fluorescent orange bead (channel). Scale bar = 200 μm. (I) Quantification from the live/dead assay. *p < 0.05.

As a control, thin gelatin hydrogels (100 μm thickness) without microchannels showed high cell viability on days 2 and 7 because, for these thin slabs, diffusion was sufficient to provide fresh media throughout the entire volume (Figure S5). Interestingly, the presence of microchannels and media perfusion also lead to fibroblast elongation and cell network formation on days 2 and 7 (Figure 3D and 3G), whereas fibroblasts encapsulated within hydrogels without channels maintained a rounded morphology. Fibroblasts cultured for 7 days in the thin gelatin hydrogels under static conditions also exhibited similar elongation (Figure S5). Anchorage-dependant fibroblasts can only survive when attached to extracellular matrix and a stretched cell morphology is both an indication of health and necessary for migration, proliferation and differentiation.[14, 43, 44] It is known that gelatin, the denatured form of collagen, retains MMP-sensitive degradation sites.[12] Therefore, local degradation of gelatin hydrogels by MMP released from fibroblasts likely enables cell elongation and invasion into the matrix. Thus, we observed that perfusion of the microfluidic hydrogels improved both cell viability and functional phenotype. This is most likely due to achieving effective mass transport throughout the hydrogel construct by the microchannel network. Although fluid sheer stress can hasten hydrogel degradation and encourage changes to cell morphology, the observed similarities between fibroblast elongation in perfused hydrogel compared to the thin hydrogel maintained under static conditions suggest that fluid sheer is not a major contributing factor explaining cell behavior and morphology in these experiments.

In summary, we have presented a method to create 3D perfusable capillary-like microchannel networks in cell-laden gelatin hydrogels using sacrificial PNIPAM fibers. The use of PNIPAM as a sacrificial material leverages the attractive combination of a thermal trigger at a threshold between room and physiological temperatures, cytocompatibility, and ease of handling. Solvent-spun PNIPAM microfibers yielded capillary-like microchanels networks with sizes, densities, and complexity that have not been achieved using more traditional patterning approaches. Perfusion of the tissue-scale hydrogels improved cell viability significantly compared to channel-less and non-perfused counterparts, indicating adequate soluble compound exchange for supporting high density of metabolically-active cells throughout a hydrogel construct. Future studies may investigate optimization of these small vessel network architectures based on the unique metabolic demands of various engineered tissue varieties and co-culture systems. Combined with more traditional techniques for patterning larger vessel structures, this work will enable the fabrication of multiscale vasculature throughout thick constructs and thus further accelerate efforts towards engineering clinically relevant tissue replacements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH R00EB013630 (to L.M.B), AHA Grant-in-Aid 15GRNT25710148 (to L.M.B. and H-J. S.), NIH EB019509 (to H-J. S.) and NSF 1506717 (to H-J. S. and L.M.B.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jung Bok Lee, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States; Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States

Dr. Xintong Wang, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States

Dr. Shannon Faley, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States

Bradly Baer, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States.

Daniel A. Balikov, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States

Prof. Hak-Joon Sung, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States

Prof. Leon M. Bellan, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States; Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, United States.

References

- [1].Langer R, Vacanti JP. Science. 1993;260:920. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Luo Y, Lode A, Gelinsky M. Adv Healthc Mater. 2013;2:777. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Peppas NA, Hilt JZ, Khademhosseini A, Langer R. Advanced Materials. 2006;18:1345. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Slaughter BV, Khurshid SS, Fisher OZ, Khademhosseini A, Peppas NA. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3307. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Annabi N, Nichol JW, Zhong X, Ji C, Koshy S, Khademhosseini A, Dehghani F. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16:371. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Griffith CK, Miller C, Sainson RC, Calvert JW, Jeon NL, Hughes CC, George SC. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:257. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Moya ML, Hsu YH, Lee AP, Hughes CC, George SC. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2013;19:730. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hsu Y-H, Moya ML, Hughes CCW, George SC, Lee AP. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13:2990. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50424g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chen X, Aledia AS, Ghajar CM, Griffith CK, Putnam AJ, Hughes CC, George SC. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:1363. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jeon JS, Bersini S, Gilardi M, Dubini G, Charest JL, Moretti M, Kamm RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417115112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tocchio A, Martello F, Tamplenizza M, Rossi E, Gerges I, Milani P, Lenardi C. Acta biomaterialia. 2015;18:144. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nichol JW, Koshy ST, Bae H, Hwang CM, Yamanlar S, Khademhosseini A. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5536. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nikkhah M, Eshak N, Zorlutuna P, Annabi N, Castello M, Kim K, Dolatshahi-Pirouz A, Edalat F, Bae H, Yang Y, Khademhosseini A. Biomaterials. 2012;33:9009. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Miller JS, Stevens KR, Yang MT, Baker BM, Nguyen DH, Cohen DM, Toro E, Chen AA, Galie PA, Yu X, Chaturvedi R, Bhatia SN, Chen CS. Nat Mater. 2012;11:768. doi: 10.1038/nmat3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kolesky DB, Truby RL, Gladman AS, Busbee TA, Homan KA, Lewis JA. Adv Mater. 2014;26:3124. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Morgan JP, Delnero PF, Zheng Y, Verbridge SS, Chen J, Craven M, Choi NW, Diaz-Santana A, Kermani P, Hempstead B, Lopez JA, Corso TN, Fischbach C, Stroock AD. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1820. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chen P-Y, Yang K-C, Wu C-C, Yu J-H, Lin F-H, Sun J-S. Acta biomaterialia. 2014;10:912. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wong KHK, Truslow JG, Tien J. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4706. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Price GM, Wong KHK, Truslow JG, Leung AD, Acharya C, Tien J. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6182. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ling Y, Rubin J, Deng Y, Huang C, Demirci U, Karp JM, Khademhosseini A. Lab Chip. 2007;7:756. doi: 10.1039/b615486g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chrobak KM, Potter DR, Tien J. Microvascular Research. 2006;71:185. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Choi NW, Cabodi M, Held B, Gleghorn JP, Bonassar LJ, Stroock AD. Nat Mater. 2007;6:908. doi: 10.1038/nmat2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Gauvin R, Chen Y-C, Lee JW, Soman P, Zorlutuna P, Nichol JW, Bae H, Chen S, Khademhosseini A. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3824. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mironov V, Visconti RP, Kasyanov V, Forgacs G, Drake CJ, Markwald RR. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2164. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhao L, Lee VK, Yoo SS, Dai G, Intes X. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5325. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lee V, Lanzi A, Ngo H, Yoo S-S, Vincent P, Dai G. Cel. Mol. Bioeng. 2014;7:460. doi: 10.1007/s12195-014-0340-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lee VK, Kim DY, Ngo HG, Lee Y, Seo L, Yoo SS, Vincent PA, Dai GH. Biomaterials. 2014;35:8092. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cui X, Boland T. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6221. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Golden AP, Tien J. Lab on a Chip. 2007;7:720. doi: 10.1039/b618409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bellan LM, Singh SP, Henderson PW, Porri TJ, Craighead HG, Spector JA. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1354. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hooper RC, Hernandez KA, Boyko T, Harper A, Joyce J, Golas AR, Spector JA. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2014;20:2711. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tocchio A, Tamplenizza M, Martello F, Gerges I, Rossi E, Argentiere S, Rodighiero S, Zhao W, Milani P, Lenardi C. Biomaterials. 2015;45:124. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bellan LM, Pearsall M, Cropek DM, Langer R. Advanced Materials. 2012;24:5187. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Khattak SF, Bhatia SR, Roberts SC. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:974. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yamada N, Okano T, Sakai H, Karikusa F, Sawasaki Y, Sakurai Y. Die Makromolekulare Chemie, Rapid Communications. 1990;11:571. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yamato M, Utsumi M, Kushida A, Konno C, Kikuchi A, Okano T. Tissue Eng. 2001;7:473. doi: 10.1089/10763270152436517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shimizu T, Yamato M, Isoi Y, Akutsu T, Setomaru T, Abe K, Kikuchi A, Umezu M, Okano T. Circulation research. 2002;90:e40. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.105722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sasagawa T, Shimizu T, Sekiya S, Haraguchi Y, Yamato M, Sawa Y, Okano T. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1646. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Okano T, Yamada N, Sakai H, Sakurai Y. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1993;27:1243. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820271005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Jiang ZL, Kassab GS, Fung YC. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:882. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.2.882. 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kassab GS, Berkley J, Fung YC. Ann Biomed Eng. 1997;25:204. doi: 10.1007/BF02738551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Faley S, Seale K, Hughey J, Schaffer DK, VanCompernolle S, McKinney B, Baudenbacher F, Unutmaz D, Wikswo JP. Lab on a Chip. 2008;8:1700. doi: 10.1039/b719799c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Science. 1997;276:1425. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lee HJ, Sen A, Bae S, Lee JS, Webb K. Acta biomaterialia. 2015;14:43. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Faley S, Baer B, Richardson M, Larsen T, Bellan LM. RSC Internet Services, Chips and Tips. 2015 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.