Summary

Angiosarcoma/lymphangiosarcoma is a rare malignancy with poor prognosis. We generated a mouse model with inducible endothelial cell-specific deletion of Tsc1 to examine mTORC1 signaling in lymphangiosarcoma. Tsc1 loss increased retinal angiogenesis in neonates, and led to endothelial proliferative lesions from vascular malformations to vascular tumors in adult mice. Sustained mTORC1 signaling was required for lymphangiosarcoma development and maintenance. Increased VEGF expression in tumor cells was seen, and blocking autocrine VEGF signaling abolished vascular tumor development and growth. We also found significant correlations between mTORC1 activation and VEGF, HIF1α, and c-Myc expression in human angiosarcoma samples. These studies demonstrated critical mechanisms of aberrant mTORC1 activation in lymphangiosarcoma, and validate the mice as a valuable model for further study.

Keywords: Vascular tumor, Angiosarcoma, Lymphangiosarcoma, mTORC1 signaling, Mouse models, VEGF, vascular anomalies

Introduction

The establishment and remodeling of blood and lymphatic vessels is tightly controlled by several signaling pathways. Disruption or aberrations of these pathways can lead to vascular tumors or malformations according to their clinical behavior and endothelial cell (EC) characteristics. Vascular tumors are formed from endothelial hyperplasia; vascular malformations have a quiescent endothelium (Enjolras and Mulliken, 1997). Angiosarcomas are rare but malignant vascular tumors derived from the abnormal proliferation of ECs. The prognosis for patients is very poor, with a reported 5-year survival rate of approximately 10% (Pawlik et al., 2003).

Lymphangiosarcomas are angiosarcomas with lymphatic differentiation. Morphologic diagnosis of lymphangiosarcomas is usually impossible, so pathologists have used the term angiosarcoma to encompass both. Recently, antigens preferentially expressed by lymphatic ECs (VEGFR3, PROX1, LYVE1 and Podoplanin) have been discovered, which allow lymphangiosarcomas to be defined pathologically (Mankey et al., 2010; Miettinen and Wang, 2012; Quarmyne et al., 2012). Inherited vascular malformations allowed identification of genetic causes for some vascular anomalies (Enjolras et al., 2007). For example, Milroy’s primary congenital lymphedema to VEGFR3 (Karkkainen et al., 2000). Nevertheless, our understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying vascular anomalies is still limited. The initiating molecular events in existing animal models of vascular tumors are largely uncharacterized and their relevance to human vascular tumors is uncertain (Cohen et al., 2009).

Mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a serine/threonine kinase that coordinates numerous cellular processes (Foster and Fingar, 2010). Dysfunction of mTORC1 signaling has been implicated in diseases including vascular tumors and malformations (Du et al., 2013; Shirazi et al., 2007). Knockdown of S6K reduced vascular tumor cell proliferation and migration, and topical application of rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTORC1, inhibited vascular tumor growth in a mouse xenograft model (Du et al., 2013). mTORC1 is also implicated in EC transformation in Kaposi’s sarcoma, a subtype of vascular tumor, through a series of elegant studies by Gutkind and colleagues. These studies showed that a G protein-coupled receptor activates Akt/mTORC1 signaling to induce sarcomagenesis (Montaner et al., 2003; Sodhi et al., 2006). Rapamycin has been successfully used for treating Kaposi’s sarcoma in humans (Stallone et al., 2005) and has shown promising results in clinic trials treating other vascular anomalies (Hammill et al., 2011; Lackner et al., 2015; Riou et al., 2012). Studies link mTORC1 signaling and vascular anomalies, but it remains to be determined whether hyperactivation of mTORC1 in ECs is sufficient to induce angiosarcomas with aggressive and metastatic features responsible for lethality.

mTORC1 is negatively regulated by tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) tumor suppressor proteins TSC1 and TSC2 (Kwiatkowski, 2003). Mutations in TSC1 or TSC2 result in benign malformations or tumors in many different organs, including lymphangioleiomyomatosis in the lungs, and angiomyolipomas in the kidney (Crino et al., 2006). VEGFA, a downstream effector of the mTORC1 (El-Hashemite et al., 2003), is a robust mitogen for ECs. Vascular tumors have been shown to express high levels of VEGFA (Boscolo and Bischoff, 2009), which may result in autocrine stimulation of neoplastic ECs. Elevated VEGFA in hemangiomas can be reduced by rapamycin (Medici and Olsen, 2012), suggesting a potential link between TSC/mTORC1 signaling and vascular tumors. However, it is not clear whether increased mTORC1 signaling is a downstream effect or plays an early and causal role in the development of vascular tumors.

RESULTS

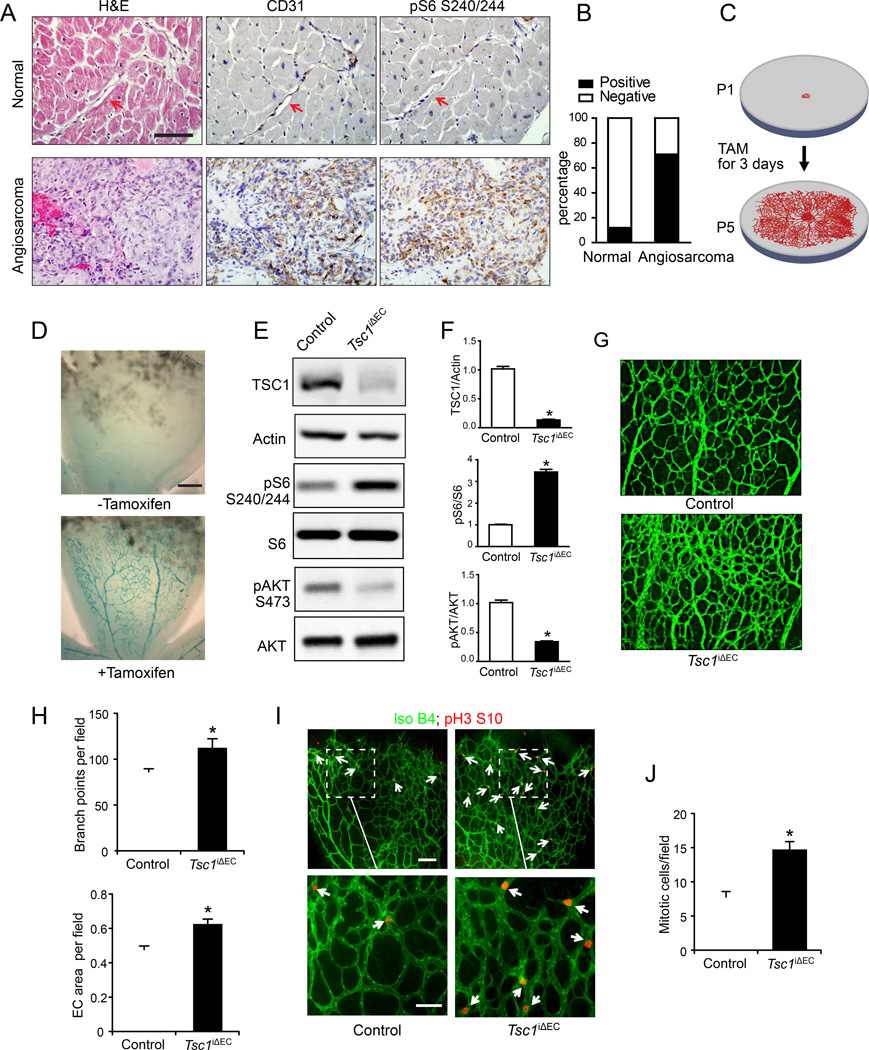

Human angiosarcomas show increased mTORC1 signaling

We prepared tissue arrays of multiple human angiosarcoma samples and checked signaling pathway changes by immunohistochemistry. mTORC1 signaling was highly activated in human angiosarcomas. The majority of angiosarcoma samples (46/65, or 71%, p< 0.01) showed strong staining for phosphorylated S6 (pS6), a marker for mTORC1 activation (Figures 1A, B and S1), whereas few quiescent blood vessels in normal tissues were positive (4/32, or 12%). These data raised the possibility that deregulated mTORC1 signaling plays a role in the development of human angiosarcomas.

Figure 1. Increased mTORC1 signaling in human angiosarcomas and mTORC1 activation promotes neonatal retinal angiogenesis in Tsc1iΔEC mice.

(A) IHC of CD31 (marker for ECs) and pS6 for representative human quiescent blood vessels in normal tissue and human angiosarcoma samples. Arrows mark the normal ECs. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Quantitative analysis of pS6 staining within normal ECs and angiosarcoma samples. Fisher exact test. p <0.01. (C) Schematic for the inducible gene deletion in postnatal retinal ECs. (D) X-gal staining for p5 retinas of Tsc1f/f;Rosa 26;Scl-Cre-ERT mice. Scale bar, 250 µm. (E, F) Lysates from primary lung ECs of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice at P5 were analyzed by immunoblotting using various antibodies as indicated (E) and the levels of TSC1, pS6, and pAKT are quantified (F). Mean ±SEM, n=3, *, p <0.05. (G, H) Representative images of whole-mount staining for isolectin B4 of retinas from control and Tsc1iΔEC mice at P5 (G) and quantification results of branch points and vessel area per field (H). Scale bar, 100 µm. Mean ±SEM. (I, J) Representative images of whole-mount retinal vasculatures of control and Tsc1iΔEC at P5 stained by isolectin B4 (green) and pH3 (red) (I) and quantification of mitotic cells (pH3 positive, marked by arrows) per field (J). Scale bar in the top panels, 100 µm. Scale bar in the bottom panels, 50 µm. Mean ±SEM. *, p <0.05. See also Figure S1.

mTORC1 activation promotes neonatal retinal angiogenesis in Tsc1iΔEC mice

We generated a mouse model for mTORC1 activation in ECs by specific deletion of its upstream inhibitor Tsc1. We crossed Tsc1f/f mice (Kwiatkowski et al., 2002) with End-Scl-Cre-ERT transgenic mice that express tamoxifen-activated Cre recombinase in ECs (Gothert et al., 2004) to produce Tsc1f/f;Scl-Cre mice. We used the neonatal retinal model to examine defects in postnatal angiogenesis upon Tsc1 deletion. The retina is avascular at birth, and a superficial vascular plexus grows progressively from the center toward the periphery during week 1 after birth (Pitulescu et al., 2010). Administration of tamoxifen to Tsc1f/f;Scl-Cre mice (designated as Tsc1iΔEC mice after induced Tsc1 deletion) from postnatal day 1 (P1) to P3 induced activation of Cre recombinase in the retinal endothelium (Figures 1C, D), resulting in an efficient reduction of Tsc1 expression in ECs, as measured by immunoblotting analyses of lysates of ECs from the lungs at P5 (Figures 1E, F). Increased phosphorylation of S6 was found in Tsc1iΔEC ECs relative to controls, indicating activation of mTORC1 upon Tsc1 deletion in these cells as expected. We also observed decreased Akt phosphorylation in the mutant cells, consistent with previous reports of its feedback inhibition by activated mTORC1 (Foster and Fingar, 2010)(Figures 1E, F). Examination of the retinal vasculature at P5 by isolectin B4 staining showed significantly increased vascular branching and EC coverage in Tsc1iΔEC retinas compared to controls (Figures 1G, H).

We next examined EC proliferation in the sprouting vessels by staining for phosphorylated histone H3 (pH3) to identify mitotic cells (Figure 1I, arrows). pH3 positive ECs were mostly in the periphery of the sprouting vasculature in control retinas, but were detected in both peripheral and central locations of the vessels in Tsc1iΔEC retinas. Quantitative analysis of pH3 labeling showed an approximately 2-fold increase in the number of mitotic cells per field in Tsc1iΔEC retinas (Figure 1J). These results suggest that hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling upon Tsc1 loss leads to increased postnatal angiogenesis and abnormal vascular patterning by promoting EC proliferation.

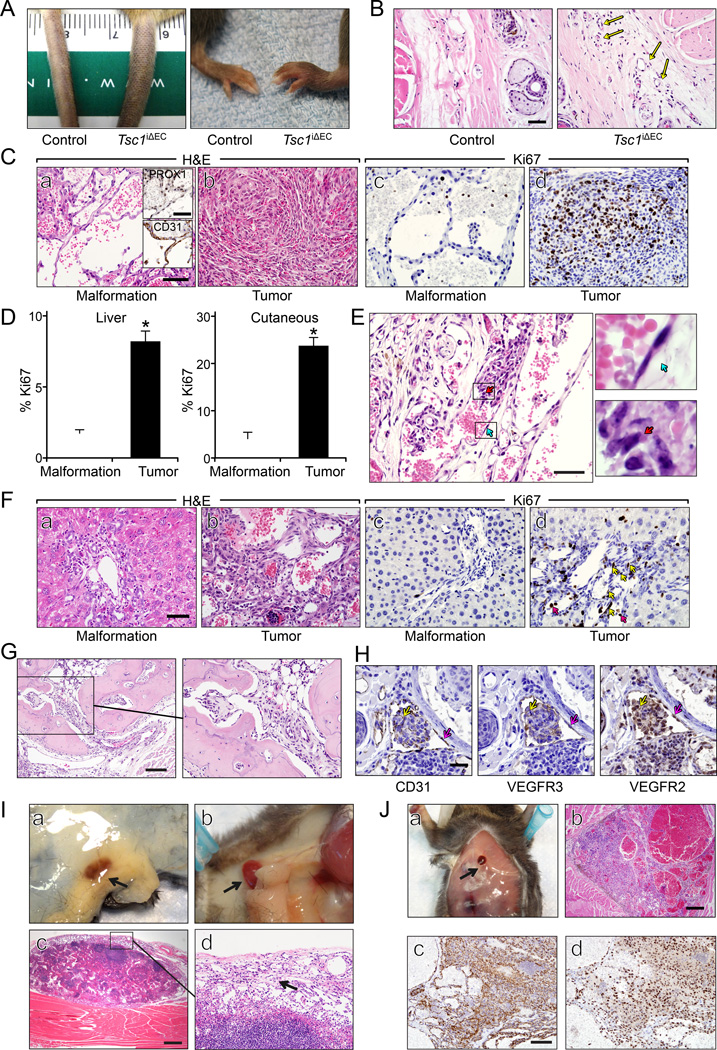

Development of vascular tumors with EC-specific Tsc1 deletion in adult mice

Unlike embryonic and neonatal ECs which undergo rapid proliferation during angiogenesis, adult ECs have a low rate of turnover under normal conditions (Hobson and Denekamp, 1984). To evaluate the effect of Tsc1 loss in ECs of adult mice, we administered tamoxifen to 2-month-old Tsc1f/f;Scl-Cre mice and control Tsc1f/f mice (Figure S2A). At 3 months or more after tamoxifen treatment, Tsc1iΔEC mice developed cutaneous tumors in tails and paws (Figure 2A). MRI scans also revealed tumor formation in the livers of Tsc1iΔEC mice (Figure 2B, arrows in right panel), confirmed at necropsy (Figure 2C). At 3–4 months after tamoxifen administration, nearly half of the Tsc1iΔEC mice had developed liver tumors and about 30% had cutaneous tumors (Figure 2D). By 6–8 months after tamoxifen, almost all the Tsc1iΔEC mice developed liver tumors, and about 80% showed cutaneous tumors (Figure 2E). At the later time point, cutaneous tumors were also observed in other areas such as lips and legs, although at lower frequencies. Tsc1iΔEC mice had a significantly reduced lifespan (Figure 2F). No cutaneous or liver vascular anomalies were found in the control mice with the same tamoxifen treatment at any time, and they lived beyond one year as expected. Similar tail and liver tumors were observed in a small fraction of either Tsc1+/− or Tsc2+/− heterozygous mice (Kwiatkowski et al., 2002; Onda et al., 1999). Therefore, our results validate the critical role of mTORC1 activation in the development of these tumors, indicate the EC origin of the tumor, and provide a mouse model with high penetrance.

Figure 2. Tsc1iΔEC mice develop vascular tumors.

(A) Representative images of tail and paw tumors of Tsc1iΔEC mice. (B) MRI images of control and Tsc1iΔEC mouse livers. Arrows mark the tumors. (C) Macroscopic appearance of representative livers of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice. Arrows mark the tumor masses. (D, E) Percentage of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice with liver and cutaneous tumors at 3–4 months (D) and 6–8 months (E). N.D., not detected. (F) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice. (G) H&E staining of liver and cutaneous sections of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice. The boxed regions are enlarged to show the cell morphology. Scale bar, 50 µm. (H) Representative microCT images of vascular casting of control and Tsc1iΔEC liver vasculatures. The boxed regions in the right panel are enlarged to show the multiple irregular vascular channels in the neoplasm area. (I) IHC for CD31 and PROX1 of liver and cutaneous sections of Tsc1iΔEC mice. Scale bar, 50 µm. See also Figure S2.

Histological examination of liver sections of Tsc1iΔEC mice showed increased numbers of portal vein profiles within the portal tracts expanding into the adjacent lobular hepatic parenchyma. These lesions were well-differentiated and composed of anastomosing vascular channels lined by hyperplastic and atypical ECs (Figure 2G, panel b). Analysis of the liver vascular networks by vascular casting and microCT imaging showed organized, hierarchical branching patterns in Ctrl mice (Figure 2H, left). In Tsc1iΔEC mice, however, multiple irregular vascular tributaries were observed in the neoplasm area. Nevertheless, they still connected to the main hepatic vasculature, consistent with benign biological behavior (Figure 2H, right). This histology is consistent with at least an atypical vascular malformation or a benign low grade vascular tumor. Similar liver tumors (liver hemangiomas) were observed in Tsc1+/− heterozygous mice (Kwiatkowski et al., 2002). The atypical ECs expressed EC markers CD31 and vWF, but not lymphatic EC markers PROX1, Podoplanin, or VEGFR3 (Figures 2I, S2B). The liver vascular lesions likely arose from differentiated ECs with a more restricted vascular phenotype.

In contrast to the benign liver lesions, histological examination of the cutaneous vascular anomalies demonstrated infiltrative masses within the dermis and subcutis comprised of solid areas of bundles and whorls of poorly defined spindled ECs with minimal to no erythrocytes (Figure 2G, panel d) and more differentiated areas with anastomosing vascular channels with epithelioid ECs with lumina occasionally containing organizing thrombi. In some mice, these vascular sarcomatous areas are associated with a vascular malformation composed of thin walled round to irregular nonanastomosing vascular channels lined by round to oval ECs. These vessels lack pericytes and smooth muscle within the wall. The neoplastic cells were strongly immunoreactive to CD31, PROX1, Podoplanin and VEGFR3 consistent with lymphangiosarcoma (Figures 2I, S2B). PROX1 expression in vascular tumors was reported in a recent study of human patient samples (Miettinen and Wang, 2012). Our results suggested that the cutaneous tumors were derived from lymphatic ECs or less differentiated endothelial precursors with the potential for vascular or lymphatic differentiation.

Vascular tumor progression and metastasis in Tsc1iΔEC mice

As early as one month after tamoxifen administration, some Tsc1iΔEC mice showed signs of edema with swelling in paws and tails (Figure 3A), which correlated with hyperplasia of PROX1 positive lymphatic channels within the dermis (Figure 3B, S3). Chronic lymphedema is a risk factor for lymphangiosarcoma in humans (Azurdia et al., 1999). At later time points (~8 weeks), we observed cutaneous vascular lesions of thin-walled, well-differentiated vascular channels, consistent with vascular malformations (Figure 3C, panel a). These early lesions showed positive PROX1 staining (see insets), suggesting that they were lymphatic malformations, although they contained various amount of blood. Moreover, these malformations had a low Ki67 proliferative index of 2%–3% (Figure 3C, panel c; Figure 3D), compared to nearly 0% for normal ECs. They may have been lesions that would develop into malignant lymphangiosarcomas at a later time in Tsc1iΔEC mice, with solid tumor masses and an elevated Ki67 index of about 30% (Figure 3C, panels b, d; Figure 3D). In some samples, both malformation and lymphangiosarcoma could be found in the same tumor, representing a lesion in the process of transition from malformation to lymphangiosarcoma (Figure 3E). In these, the vascular malformation ECs still showed the normal flat shape (blue arrows, upper right), whereas those in the lymphangiosarcoma portion have an atypical plump appearance with vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli (red arrows, lower right).

Figure 3. Tumor progression and metastasis in Tsc1iΔEC mice.

(A) Representative images of edema of Tsc1iΔEC paw and tail at 1 month after tamoxifen injection. (B) H&E staining of cutaneous sections of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice 1 month after tamoxifen injection. Arrows mark the increased small vessels. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) H&E staining and IHC for PROX1, CD31, and Ki67 of cutaneous vascular malformation and lymphangiosarcoma. Scale bar, 50 µm. Scale bar in the insets, 50 µm. (D) Mean ±SEM of percentage of Ki67+ ECs in liver and cutaneous sections. *, p <0.05. (E) A representative image of cutaneous tumor section shows the transition from malformation to lymphangiosarcoma. Boxed regions in the left panel are enlarged in the right. Note the ECs transit from normal flat shape (blue arrow) to atypical and neoplastic (red arrow). Scale bar, 50 µm. (F) H&E staining and IHC for Ki67 of liver vascular malformation and tumor. Yellow arrows mark proliferating ECs. Red arrows indicate blood cells that are also Ki67 positive. Scale bar, 50 µm. (G) H&E staining of a bone section of Tsc1iΔEC mice showing infiltration by cutaneous lymphangiosarcoma. The boxed area is shown in more detail on the right. Scale bar, 250 µm. (H) IHC for CD31, VEGFR3 and VEGFR2 of cutaneous tumor sections of Tsc1iΔEC mice. Yellow arrows mark a metastatic nodule and red arrows mark the lymphatic vessels. Scale bar, 50 µm. (I) An example of macrometastasis of cutaneous lymphangiosarcoma to the inguinal (a) and cervical (b) lymph nodes (red, marked by arrows) of Tsc1iΔEC mice. H&E staining of lymph node metastasis (c) and an enlarged area (d, arrow marks tumor cells). Scale bar, 500 µm. (J) A representative macrometastasis on the sternal musculature of Tsc1iΔEC mice (a) and H&E staining (b) and IHC for CD31 (c) and PROX1 (d) of this macrometastasis. Scale bar, 500 µm in (b) and 100 µm in (c, d). See also Figure S3.

One month after tamoxifen injection, liver sections of Tsc1iΔEC mice showed localized areas with increased portal vein profiles (Figure 3F, panel a). Tumor compression was not identified within the main portal vein, but by imaging there were malformed branches of the portal arteriovenous system that suggested gross localized lesions. These areas of increased portal veins represent localized venous malformations with no atypia and low proliferative index of 2% (Figure 3F, panel c; Figure 3D). Similar to the cutaneous lesions, the liver venous malformations were probably in transition to larger liver lesions that contained anastomosing vascular channels with areas suggestive of atypical venous malformation to low grade benign vascular tumors with increased proliferative index of 8% at later time points (Figure 3F, panels b, d; Figure 3D).

The poorly differentiated cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas of Tsc1iΔEC mice were highly invasive and on the extremities, frequently showed local invasion into bone (Figure 3G). Small metastatic nodules were found in the lymphatic vessels near the primary tumors (Figure 3H). The metastatic cells (yellow arrows) in the nodules expressed EC markers CD31 and VEGFR2 and lymphatic EC marker VEGFR3, which also stained lymphatic vessels (red arrows) as expected. Macrometastases were commonly present in lymph nodes (Figure 3I) and also found at lower frequencies in distant sites such as the sternal musculature (Figure 3J). The tumor cells at these sites also stained positively for CD31 and PROX1, suggesting that these macrometastases and micrometastatic nodules were derived from primary cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas in the Tsc1iΔEC mice. These results demonstrate that Tsc1 deletion in adult ECs leads to vascular malformations that may progress to malignant cutaneous lymphangiosarcoma. They recapitulate many features of human lymphangio/angiosarcomas including invasion and metastasis (Pawlik et al., 2003), suggesting the utility of the Tsc1iΔEC mice as a model for human vascular tumors.

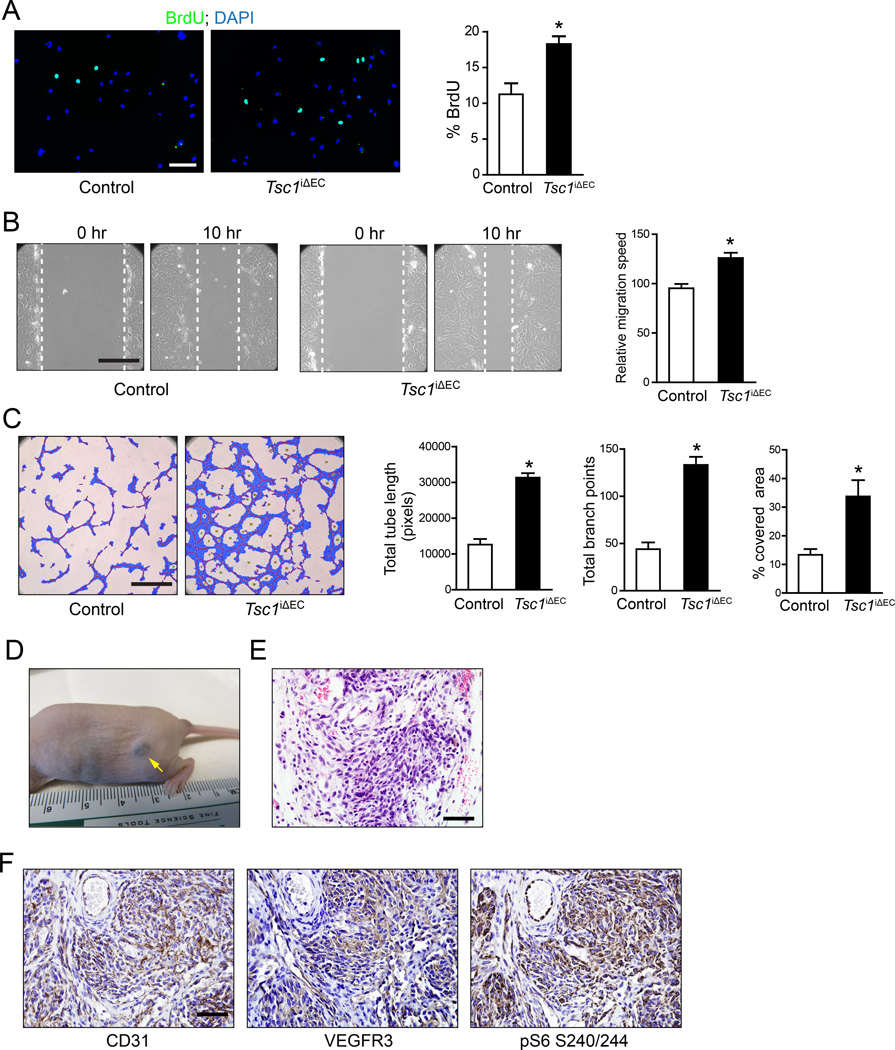

Increased proliferation and migration of Tsc1iΔEC tumor cells contribute to vascular tumor development and progression in a cell-autonomous manner

To investigate mechanisms, primary cells were isolated from cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas of Tsc1iΔEC mice and lungs of control Tsc1f/f mice. Tsc1iΔEC ECs and control primary ECs were of high purity based on their morphology, staining with CD31, and DiI-Ac-LDL uptake assays (Figure S4). As expected, Tsc1iΔEC ECs showed significantly decreased Tsc1 expression compared to controls (see Figure 6B below). Consistent with the results in vivo, Tsc1iΔEC ECs showed increased proliferation in vitro as measured by BrdU incorporation (Figure 4A). Analysis of cell migration using wound closure assay showed increased migration of Tsc1iΔEC ECs compared to controls (Figure 4B). We next assessed the angiogenic activity of Tsc1iΔEC ECs using a Matrigel culture capillary formation assay, a process that mimics sprouting and tube formation during angiogenesis in vivo. As shown in Figure 4C, Tsc1iΔEC ECs had significantly increased tubule formation relative to controls, measured by tubule length, number of branch points, and percentage of area covered by ECs.

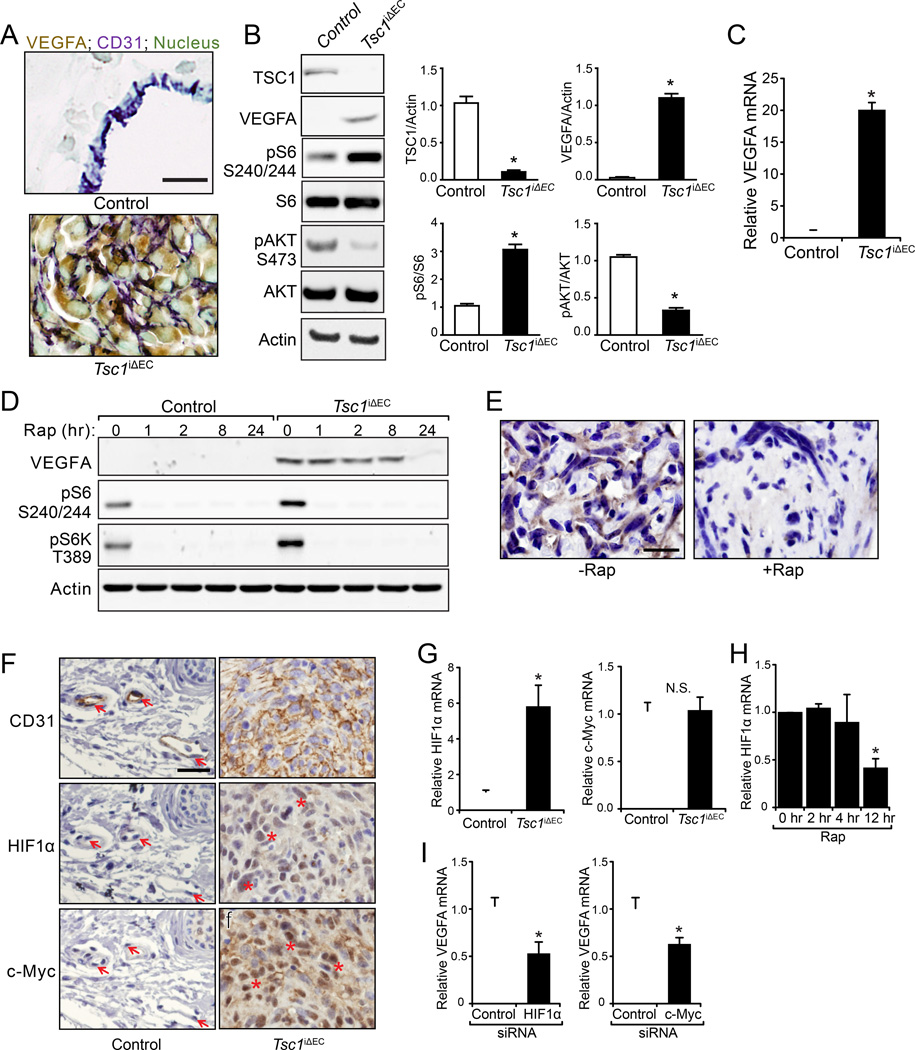

Figure 6. Increased VEGF transcription through HIF1α and c-Myc in Tsc1iΔEC tumor cells.

(A) Double IHC for VEGFA and CD31 of the normal blood vessels in control mice and cutaneous tumor sections of Tsc1iΔEC mice. Nuclei were counterstained with methyl green. Scale bar, 20 µm. (B) Lysates from primary lung ECs of control mice and cutaneous tumor ECs of Tsc1iΔEC mice were analyzed by immunoblotting using various antibodies as indicated and the levels of TSC1, VEGFA, pS6 and pAKT were quantified. Mean ±SEM, n=3 *, p <0.05. (C) Mean ±SEM of mRNA (normalized to control ECs as 1) of VEGFA in cutaneous tumor cells of Tsc1iΔEC mice. (D) Isolated control and tumor ECs were treated with rapamycin for indicated times. Lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using various antibodies as indicated. (E) IHC for VEGFA of liver tumors from Tsc1iΔEC mice treated with or without rapamycin. Scale bar, 20 µm. (F) IHC for CD31, HIF1α and c-Myc of cutaneous sections of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice. Arrows mark normal ECs (left panels) and asterisks indicate elevated HIF1α and c-Myc in the nuclei of cutaneous tumor cells (right panels). Scale bar, 50 µm. (G) mRNA (normalized to control ECs as 1) of HIF1α and c-Myc in control and tumor cells. (H) HIF1α mRNA in tumor ECs treated with rapamycin (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times. (I) VEGFA mRNA in tumor ECs transfected with HIF1α and c-Myc siRNA for 48 hr. Mean ±SEM, n=3. *, p <0.05. N.S., Not Significant. See also Figure S6.

Figure 4. Tsc1iΔEC tumor cells show increased proliferation, migration and tubulogenesis in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo.

(A) Representative image and quantification of analysis for proliferation by BrdU incorporation assays of primary ECs isolated from cutaneous tumors from Tsc1iΔEC mice or lungs of control mice. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) Representative image and quantification of migration by wound closure assay of cells as in (A). Scale bar, 500 µm. (C) Representative image and quantification of tube formation on Matrigel of cells as in (A). Scale bar, 1mm. All quantifications shown as Mean ±SEM. *, p <0.05. (D–F) Isolated tumor ECs were subcutaneously injected in recipient nude mice. Tumor formation at injection site (D), H&E staining (E), and IHC for CD31, VEGFR3 and pS6 of tumor sections (F) are shown for recipients of Tsc1iΔEC tumor cells. Scale bar, 50 µm. See also Figure S4.

We then injected isolated ECs subcutaneously into nude mice to evaluate their tumorigenicity. Recipient mice injected with Tsc1iΔEC ECs all developed subcutaneous tumors after one month (Figure 4D), while none of the recipient mice with control EC injections showed tumors (data not shown). Histological examination of the tumors showed features of vascular tumors (Figure 4E), which was verified by strong staining for CD31 and VEGFR3 (Figure 4F). The tumors also showed high pS6 signaling (Figure 4F), consistent with the hyperactivation of mTORC1 in Tsc1iΔEC ECs. These results suggest that increased mTORC1 signaling in Tsc1iΔEC ECs promotes EC proliferation and migration, confers increased angiogenic activity, and promotes tumorigenicity in a cell-autonomous manner.

Constitutive mTORC1 activation is required for vascular tumor initiation and maintenance

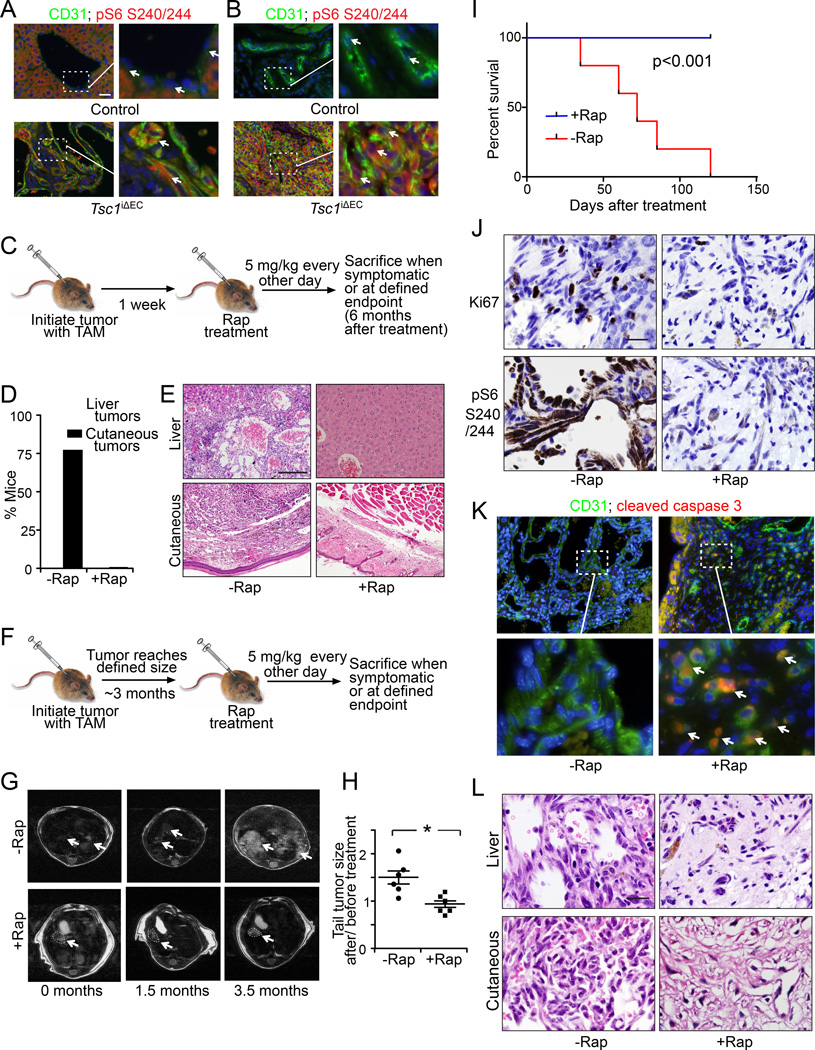

We next analyzed activation of mTORC1 signaling by measuring pS6 in tumor sections (Figure 5A, B). In contrast to the virtual absence of pS6 signals in ECs of control mouse, tumor cells in Tsc1iΔEC mice showed significantly elevated pS6 staining. These results suggested that aberrant activation of mTORC1 signaling upon Tsc1 loss is responsible for the vascular tumor development in Tsc1iΔEC mice. We did not detect increased pS6 in normal vessels in Tsc1iΔEC mice (Figure S5), suggesting that altered expression patterns are unique to the vascular lesions, possibly due to mosaic expression of Cre with tamoxifen treatment in adult mice. We next treated Tsc1iΔEC mice with the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin (5 mg/kg IP every other day) starting one week after tamoxifen injection and examined the effects for the next 6 months (Figure 5C). Mice treated with vehicle alone developed both liver and cutaneous anomalies as expected, while none of the Tsc1iΔEC mice treated with rapamycin showed either of these tumors at the same time points (Figure 5D). Histological examination of the livers and cutaneous tissues showed normal morphology for the rapamycin treated Tsc1iΔEC mice, in contrast to the vascular tumors in the vehicle treated mice (Figure 5E). These results show that aberrant hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling is required for the development of vascular tumors in the Tsc1iΔEC mice.

Figure 5. Constitutive mTORC1 activation is required for vascular tumor initiation and maintenance.

(A, B) Immunofluorescence for CD31 and pS6 in liver (A) and cutaneous (B) sections of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice. Arrows mark individual ECs. Scale bar, 50 µm. (C) Schematic of rapamycin treatment (5 mg/kg IP every other day) to examine effects on vascular tumor initiation of Tsc1iΔEC mice. (D) Percentage of Tsc1iΔEC mice with tumors in rapamycin treated and untreated group. (E) H&E staining of liver and cutaneous sections of rapamycin treated and untreated Tsc1iΔEC mice. Scale bar, 100 µm. (F) Schematic of rapamycin treatment (5 mg/kg IP every other day) to examine effects on established vascular tumors of Tsc1iΔEC mice. (G) MRI images of the livers of Tsc1iΔEC mice at various times after treatment with or without rapamycin. Arrows mark liver tumors. (H) Quantification (Mean ±SEM) of fold changes in tail tumor size at 3.5 months after rapamycin or vehicle treatment relative to before treatment (0 month). n=6, *, p <0.05. (I) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of Tsc1iΔEC mice treated with or without rapamycin. (J–L) IHC for Ki67 and pS6 (J), double immunofluorescence for CD31 and cleaved caspase 3 (K), and H&E staining (L) of vascular tumor sections from Tsc1iΔEC mice treated with or without rapamycin. Scale bar, 20 µm (J, L) or 50 µm (K). Arrows in (K) mark apoptotic ECs. See also Figure S5.

To determine if hyperactivation of mTORC1 is also necessary for the maintenance and growth of vascular tumors, Tsc1iΔEC mice were treated with rapamycin (5 mg/kg IP every other day) after the formation of tumors at 3 months after tamoxifen injection (Figure 5F). In contrast to the significant liver tumor growth in vehicle treated mice, rapamycin treatment halted and even reduced tumor size slightly, as assessed by MRI (Figure 5G). Cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas on tails grew by about 50% in size over 3.5 months in vehicle treated mice, but rapamycin abolished growth of the tumors (Figure 5H). Rapamycin-treated Tsc1iΔEC mice also exhibited significantly increased survival, with all mice still alive after more than 6 months of Tsc1 deletion (i.e., 3 months after tamoxifen injection followed by 3 additional months with rapamycin treatment), when a significant fraction of vehicle treated mice had died (Figure 5I, 2F). Ki67 staining showed corresponding decreases in tumor cell proliferation after rapamycin treatment (Figure 5J), elevated pS6 was abolished (Figure 5J), and staining for cleaved caspase 3 showed significantly increased apoptotic ECs (Figure 5K). Histological examinations of liver and cutaneous sections showed the presence of scar tissue replacing the vascular tumor cells of Tsc1iΔEC mice after rapamycin treatment (Figure 5L). This was similar to the spontaneous selfinvoluting phase of infantile hemangioma, which often leaves behind scar tissue (Greenberger and Bischoff, 2011). These results indicate that sustained hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling is necessary for vascular tumor growth and maintenance in Tsc1iΔEC mice, suggesting that mTORC1 inhibitors could be useful in treating vascular tumors.

Increased VEGF transcription through HIF1α and c-Myc in vascular tumor cells

Having established a role for aberrant hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling in the development of vascular tumors in Tsc1iΔEC mice, we next examined mechanism. We focused on a well-characterized downstream target controlled by mTORC1 signaling, VEGFA, a critical regulator of angiogenesis and other vascular functions of ECs. We examined VEGFA expression in the vascular tumors in Tsc1iΔEC mice compared to cutaneous ECs of controls. Consistent with previous studies (Maharaj et al., 2006), we did not detect VEGFA expression in control ECs but high VEGFA was found in ECs of the vascular tumors (Figure 6A). Interestingly, a recent paper reported on another Tsc1 deletion model by Darpp-32-Cre (expressed in brain and multiple other tissues) also observed accelerated paw angiosarcomas formation and elevated VEGF mRNA (Leech et al., 2015). To corroborate our results, we examined VEGFA expression in vitro in ECs isolated from Tsc1iΔEC tumors. Immunoblotting showed significantly elevated VEGFA, along with increased pS6, indicating mTORC1 activation in Tsc1iΔEC ECs compared to controls (Figures 6B). Increased VEGFA was also detected in the culture supernatant of Tsc1iΔEC ECs (Figure S6A). We found increased VEGFA mRNA in Tsc1iΔEC ECs, suggesting that the upregulated VEGFA expression was likely at the transcriptional level (Figure 6C). We examined VEGFA expression after rapamycin treatment and found a gradual decrease in expression to barely detectable after 24 hr (Figure 6D). Analysis of vascular tumor sections from Tsc1iΔEC mice treated with rapamycin also showed a significant decrease of VEGFA (Figure 6E). These results demonstrate that hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling is responsible for increased VEGFA expression in Tsc1iΔEC ECs, which may contribute to the development of vascular tumors.

We then examined hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1 α (HIF1α) and c-Myc expression downstream of mTORC1 (Hay and Sonenberg, 2004). In ECs, HIF-1α promotes proliferation and VEGFA expression (Tang et al., 2004). c-Myc is also a key transcription factor for VEGFA (Baudino et al., 2002). We found increased nuclear localization of activated HIF1α and c-Myc in cutaneous (Figure 6F) and liver vascular tumors (Figure S6B) of Tsc1iΔEC mice compared to the corresponding normal tissues in control mice. qRT-PCR analysis revealed significantly increased mRNA of HIF1α, but not c-Myc, in isolated Tsc1iΔEC ECs compared to controls (Figure 6G), suggesting that mTORC1 signaling regulated HIF1α transcription, but affected c-Myc post-transcriptionally. Consistent with these results, inhibition of mTORC1 by rapamycin significantly decreased HIF1α mRNA in Tsc1iΔEC ECs (Figure 6H). Knockdown of either HIF1α or c-Myc by siRNAs reduced VEGFA expression (Figure 6I), suggesting both of these transcription factors are involved in mediating VEGFA upregulation by hyperactivated mTORC1 signaling in Tsc1iΔEC ECs.

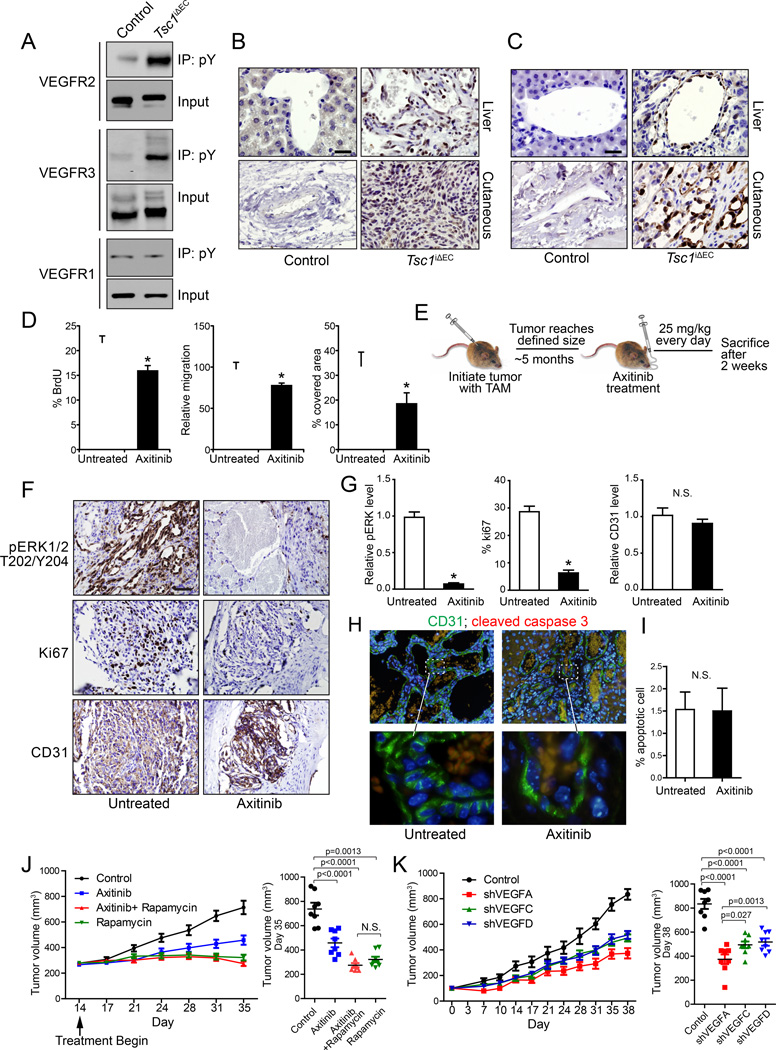

Autocrine VEGF signaling is important for the development of vascular tumors in Tsc1iΔEC mice

To evaluate the autocrine activation of VEGF signaling in tumor cells, we first assessed the activation status of VEGFRs by measuring autophosphorylation. We found that VEGFR2 and VEGFR3, but not VEGFR1, are activated in tumor ECs compared to normal lung ECs of controls (Figure 7A). We then examined VEGFR downstream targets MEK1/2 and ERK1/2. Increased MEK1/2 activation was found in vascular tumor tissues of Tsc1iΔEC mice compared to ECs in controls (Figure 7B). We also found moderate to intense pERK1/2 immunostaining in most vascular tumors from Tsc1iΔEC mice, but not ECs of controls (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for increased proliferation of Tsc1iΔEC tumor cells.

(A) Lysates from primary lungs of control mice and cutaneous tumors of Tsc1iΔEC mice were immunoprecipitated with anti-phosphotyrosine antibody 4G10 and analyzed by immunoblotting using various antibodies as indicated. (B) IHC for pMEK1/2 S221 of liver and cutaneous sections of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice. Scale bar, 25 µm. (C) IHC for pERK1/2 T202/Y204 of liver and cutaneous sections of control and Tsc1iΔEC mice. Scale bar, 25 µm. (D) Isolated cutaneous tumor cells of Tsc1iΔEC mice were analyzed for proliferation, migration, and tube formation in the presence or absence of axitinib (50 nM) in vitro. Mean ±SEM from three independent experiments. *, p <0.05. (E) Schematic of axitinib treatment (25 mg/kg daily PO) to examine effects on established vascular tumors of Tsc1iΔEC mice. (F, G) IHC (F) and quantification (G) for pERK, Ki67, and CD31 of cutaneous tumor sections of Tsc1iΔEC mice that had been treated with or without axitinib. Scale bar, 50 µm. Mean ±SEM, *, p <0.05. (H, I) Double immunofluorescence for CD31 and cleaved caspase 3 of liver tumor sections of Tsc1iΔEC mice treated with or without axitinib (H) and quantification for percentage of apoptotic cells (I). In (H), the boxed regions in the top panels are enlarged in the bottom panels. Scale bar in the top panels, 50 µm. Scale bar in the bottom panels, 10 µm. Mean ±SEM, *, p <0.05. (J) Tumor growth curves and tumor volumes of mice treated with placebo, axitinib (25 mg/kg daily), rapamycin (5 mg/kg every other day) and both axitinib and rapamycin. Tumor volumes were measured on day 35. Mean ±SEM, n=8. (K) Tumor growth curves and tumor volumes of tumor ECs with VEGFA, VEGFC or VEGFD knockdown. Tumor volumes were measured on day 38. Mean ±SEM, n=8. See also Figure S7.

We next determined the importance of autocrine activation of VEGF signaling in Tsc1iΔEC ECs and vascular tumor development in Tsc1iΔEC mice by employing a potent and selective inhibitor for VEGFRs, axitinib (Hu-Lowe et al., 2008). We found axitinib treatment reduced proliferation, migration, and tubule formation of Tsc1iΔEC ECs in vitro (Figure 7D), suggesting a role for VEGF autocrine signaling in the increased activity of Tsc1iΔEC ECs. We then tested the response of vascular tumors in the Tsc1iΔEC mice to axitinib. Starting at 5 months after tamoxifen treatment when vascular tumors were established, we administered axitinib at daily intervals to the Tsc1iΔEC mice for 2 weeks (Figure 7E). Analysis of tumor sections following treatment showed significantly decreased pERK1/2 (Figures 7F and 7G), indicating effective inhibition of VEGF signaling. After treatment, tumors showed decreased Ki67 staining but did not shrink, according to the CD31 staining (Figures 7F and 7G). The number of apoptotic cells remained similar to lesions from untreated mice (Figures 7H, 7I), suggesting that axitinib exerts an antiproliferative rather than a pro-apoptotic effect. These results suggest that increased VEGF autocrine signaling plays an important role in the development and maintenance of vascular tumors in Tsc1iΔEC mice.

Using the transplantation model (see Figure 4), we compared treatment benefits of axitinib vs rapamycin as well as potential synergy of the two inhibitors. Both axitinib and rapamycin inhibited the growth of transplanted tumors in the recipient mice. Rapamycin was more effective in completely blocking tumor growth (Figure 7J). Concurrent treatment with both did not generate synergetic effects, but showed similar inhibition as rapamycin alone. We also examined the role of increased VEGFA in tumor growth, and found that knockdown of VEGFA significantly reduced the growth of vascular tumor cells (Figure 7K). We wondered if hyperactivation of mTORC1 also increased VEGFC and/or VEGFD expression and could promote vascular tumor growth by stimulating EC proliferation as well as VEGFA (Lohela et al., 2009). Expression of both VEGFC and VEGFD were increased in vascular tumors as measured by immunoblotting and immunostaining (Figures S7A and S7B). Knockdown of either VEGFC or VEGFD also reduced vascular tumor growth, although less than VEGFA knockdown (Figures 7K and S7C). Our results demonstrate that VEGF autocrine signaling triggered by aberrant hyperactivation of mTORC1 contributes to the development of vascular tumors in Tsc1iΔEC mice, and that blockage of the VEGFR pathway could be a rational and effective therapy for human vascular tumors.

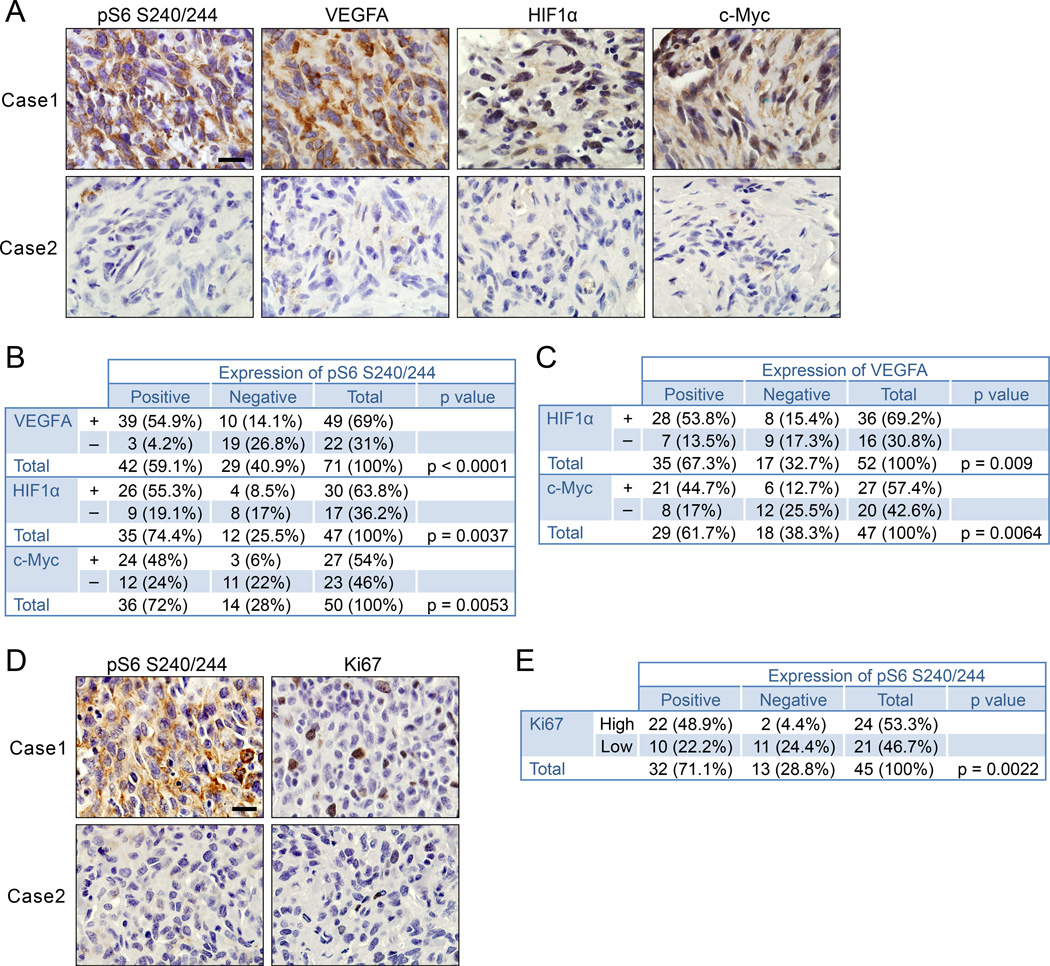

Clinical relevance of the mTORC1/VEGF pathway in human vascular tumors

To determine the clinical relevance of an mTORC1-triggered VEGF autocrine pathway in human vascular tumors, we analyzed the relationships between the signaling components pS6, VEGFA, HIF1α, and c-Myc in human angiosarcoma samples by immunohistochemistry. We found significant correlations of mTORC1 activation (measured by pS6 level) with VEGFA, HIF1α, and c-Myc expression (Figures 8A, B). We also found positive correlations between VEGFA, HIF1α, and c-Myc expression (Figure 8C). We analyzed the correlation between pS6 and the proliferative status of tumor cells of human angiosarcoma. Consistent with our mouse model, a positive correlation existed between pS6 and Ki67 staining for proliferative cells (Figures 8D, E). These results provide strong support for an important role of the VEGF autocrine loop induced by aberrant hyperactivated mTORC1 signaling in human angiosarcoma, and further validate our Tsc1iΔEC mice as a valuable model for this neoplasm.

Figure 8. Clinical relevance of mTORC1/VEGF signaling axis in human angiosarcomas.

(A) Representative images of IHC for VEGFA, HIF1α and c-Myc of samples with high and low pS6. Scale bar, 20 µm. (B, C) Correlation analyses between pS6 and VEGFA, HIF1α, or c-Myc expression (B) and between VEGFA and HIF1α or c-Myc expression (C). (D) IHC for pS6 and Ki67. Scale bar, 20 µm. (E) Relationship between pS6 and Ki67 expression, High, >=15% Ki67 positive cells; Low < 15% Ki67 positive cells. The correlative relationship between two quantitative measurements was investigated using Fisher's exact test. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Discussion

We created an inducible EC-specific Tsc1 deletion mouse model and found that hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling in ECs is sufficient to induce and maintain growth of vascular tumors that recapitulate salient features of human lymphangiosarcomas, including local invasion and systemic metastasis through the lymphatics. Our Tsc1iΔEC mouse model has a short tumor latency (3–4 months) and high penetrance (~100%) for tumor development. We demonstrated the critical role of the VEGF signaling axis in tumor development induced by HIF1α and c-Myc downstream from mTORC1. Blockade of VEGF signaling decreased tumor cell proliferation, validating this model for discovery of compounds to target important signaling molecules and pathways for lymphangiosarcoma.

Previous studies showed that some of either Tsc1+/− or Tsc2+/− mice developed vascular tumors, implying a role for mTORC1 signaling (Kwiatkowski et al., 2002; Onda et al., 1999). However, those mice were heterozygous for Tsc1 or Tsc2 in all cells and loss of the remaining functional allele was not assessed in tumors. It was not clear whether mTORC1 activation in ECs or other cells such as smooth muscle cells, which could affect ECs through cell-cell interactions or paracrine signaling, was responsible for vascular tumors. Increased VEGF was observed in serum, but its cellular origin was unknown. The inducible Cre employed in our mouse model is specific for ECs (Gothert et al., 2004). Our data establish that hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling in ECs is a driver for vascular tumor initiation.

PI3K/Akt signaling is a positive regulator for mTORC1 and has also been implicated in the development of many tumor types (Foster and Fingar, 2010), although there is as yet no direct report for its role in vascular tumors. In a mouse model with EC-specific overexpression of constitutively active myrAkt1, sustained endothelial Akt activation increased vascular permeability and pathological angiogenesis was reported, but not vascular tumors. It was also unclear whether VEGF was increased in ECs with activated Akt (Phung et al., 2006). If not, this might explain the lack of vascular tumor development in this mouse model. We showed that mTORC1 activation following Tsc1 deletion led to decreased Akt phosphorylation in ECs, consistent with previous studies indicating a feedback inhibitory mechanism (Huang et al., 2008). Activation of the mTORC1/VEGF axis upon Tsc1 deletion, independent of Akt, is sufficient to initiate the development and progression of vascular tumors.

Previous studies have shown that hyperactivation of mTORC1 signaling contributes to EC transformation in mouse models of Kaposi’s sarcoma (Sodhi et al., 2006). Kaposi’s sarcoma is a subtype of vascular tumor, but our studies describe a mouse model for the poorly studied lymphangiosarcomas, with well-defined molecular changes in relevant cells, distinct from Kaposi’s sarcoma in several important ways. Our mouse model recapitulates the invasion and metastasis of human angiosarcoma; unlike Kaposi’s sarcoma mouse models. Many human angiosarcomas and Kaposi’s sarcoma express lymphatic markers. Our model recapitulates this important feature, unlike Kaposi’s sarcoma mouse models (Montaner et al., 2003; Sodhi et al., 2006). Although mTOR activation and VEGFs are implicated in both models, there are important differences in the mechanisms revealed. Akt and mTOR signaling were activated and Akt plays a central role in sarcomagenesis in Kaposi’s sarcoma models (Montaner et al., 2001; Sodhi et al., 2004). Our studies found the Akt pathway repressed, and mTORC1 activation per se was sufficient to induce tumors. Only a small fraction (less than 5%) of Kaposi’s sarcoma tumor cells expressed vGPCR, suggesting paracrine mechanisms for VEGF (Montaner et al., 2003). In contrast, we found increased mTOR activation and VEGF expression in essentially all tumor cells, suggesting an autocrine VEGF mechanism in our mouse model.

While vascular anomalies in the liver showed positive blood EC markers only, the malignant cutaneous tumors in Tsc1iΔEC mice were positive for both blood and lymphatic EC markers. One explanation could be that liver anomalies develop from more differentiated blood ECs, while cutaneous tumors form from early endothelial precursors exhibiting a mixture of both markers. Alternatively, cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas could be developed from lymphatic ECs in the adult mice. This explanation is supported by the fact that the earliest sign of vascular abnormality in Tsc1iΔEC mice was lymphedema in the extremities, caused by hyperplasia of lymphatic vessels in cutaneous tissues. Lymphatic hyperplasia and benign malformations were prominent at early time points after Tsc1 deletion; malignant cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas were more frequent at later time points. Therefore, our data favor the possibility that early lymphatic vascular malformations can progress to cutaneous lymphangiosarcomas. Similar progressions have been seen in some clinical observations (Jeng et al., 2014; Quarmyne et al., 2012; Rossi and Fletcher, 2002).

The mechanistic insights from our model raise the immediate question of whether rapamycin and anti-VEGF/VEGFR drugs will be effective for the treatment of human vascular tumors. A recent Phase I trial showed that rapamycin is safe and potentially effective for treating patients with vascular malformations and tumors. Interestingly, all patients who responded well to rapamycin in this trial had vascular anomalies with significant lymphatic components. (Hammill et al., 2011). The strong effect of rapamycin on lymphatic-based lesions is consistent with our findings of the of cutaneous lymphangiosarcoma development in Tsc1iΔEC mice as well as the requirement of mTORC1 for tumor maintenance. Several anti-VEGF/VEGFR drugs, including axitinib are in various phases of clinical trial and some have already shown activity against angiosarcoma (Agulnik et al., 2013; Ono et al., 2012). Inhibition of VEGFs by shRNA or axitinib significantly reduced growth of vascular tumors derived from our Tsc1iΔEC mouse model. Treatment of mouse vascular tumors with rapamycin plus axitinib did not provide benefit than rapamycin alone, providing support that increased autocrine VEGF signaling is downstream of mTORC1 hyperactivation.

In summary, our studies identify a critical role for the mTORC1/VEGF signaling axis in lymphangiosarcoma development and maintenance, and establish the mouse model that recapitulates many features of human lymphangiosarcoma including invasion and metastasis. Our results provide significant insights into the molecular and cellular mechanisms of this relatively rare but highly lethal cancer. The spontaneous and heterogeneous nature of the vascular tumors in our mouse model also provides an opportunity for further investigation into the molecular and genetic mechanisms of vascular tumors as well as a powerful tool for testing therapeutic methods.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

Tsc1f/f and End-Scl-Cre-ERT mice were described previously (Gothert et al., 2004; Kwiatkowski et al., 2002). Male and female mice with more than 98% C57BL/6 backgrounds were used. Age-and littermate-matched control and mutant mice were randomly collected by genotype. Mice were housed and handled according to local, state, and federal regulations. All experimental procedures were carried out according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Michigan and the University of Cincinnati. To induce Cre activity in newborn mice, three consecutive IP tamoxifen injections (10 µl, 10 mg/ml in corn oil) (Sigma) were given on postnatal day P1, P2, and P3. To induce Cre activity in adult mice, three consecutive IP tamoxifen injections (100 µl, 10 mg/ml in corn oil) (Sigma) were given about 2 months after birth. Control Tsc1f/f mice received the same tamoxifen treatment.

Mouse tumor transplantation

Vascular tumor cells were isolated from cutaneous tumors. 1.5 × 106 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice per site. Tumor volumes were measured two times per week by caliper and calculated according to the following equation: 0.5 × [length × (width)2]. For rapamycin treatment, mice received 5 mg/kg rapamycin IP every other day. For axitinib treatment, mice received 25 mg/kg orally daily. For shRNA experiments, cells were infected by lentivirus (Sigma, VEGFA TRCN0000304451, VEGFC TRCN0000328200, VEGFD TRCN0000425215, scramble SHC002) and selected by puromycin.

Human tissues and histologic scoring

Human angiosarcoma tissue arrays were obtained from the Department of Pathology, University of Michigan Medical School. Specimen collection and use of human tissue samples were approved by the Medical School Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The specimens were stained with antibodies indicated. The intensity of staining was ranked into four groups (0–3) according to histologic scoring. Scores 2 and 3 were designated positive; scores 1 and 0 were designated negative. Ki67 labeling index: “High” > 15% Ki67+ cells; “Low” < 15% Ki67+ cells.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between 2 groups was evaluated by two-tailed Student's t-test. Survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Fisher's exact test was used to examine correlations between quantitative measurements. p <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Analyses used GraphPad Prism.

Further or detailed experimental procedures are described in the Supplemental Information.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Angiosarcoma/lymphangiosarcoma is a rare cancer that currently has no effective treatment. The mechanism of angiosarcoma development is largely unknown, and there is no animal model for the disease with molecularly defined pathogenesis. Here we describe a mouse model with inducible mTORC1 activation exclusively in endothelial cells that resulted in lymphangiosarcoma development and progression and recapitulated salient features of human tumors including invasion and metastasis. We identified the VEGF autocrine signaling loop as a critical event downstream of mTORC1 for vascular tumor development and growth. mTORC1 inhibition by rapamycin or VEGF blockade effectively abolished vascular tumor development and growth. This study provides significant mechanistic insights and potential future therapies for a previously poorly characterized but deadly cancer.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. D. J. Kwiatkowski for Tsc1f/f mice and Dr. G. Begley for End-Scl-Cre-ERT transgenic mice. We thank the MicroCT Core and the Center for Molecular Imaging at the University of Michigan for microCT and MRI; A. Serna and J. Wen for assistance, our colleagues Drs. C. Wang, S. Yeo, and J. Wen for discussions, help, and comments; Drs. M. Czyzyk-Krzeska, D. Plas, E. Boscolo and L. Chow for critical reading of the manuscript and insightful suggestions; G. Doerman for preparing figures; and Dr. B. Peace for editing. This research was supported by NIH grant HL073394, CA163493 and CA150926 to J.-L. Guan; and AR062030 and DE021718 to F. Liu.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agulnik M, Yarber JL, Okuno SH, von Mehren M, Jovanovic BD, Brockstein BE, Evens AM, Benjamin RS. An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of bevacizumab for the treatment of angiosarcoma and epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:257–263. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azurdia RM, Guerin DM, Verbov JL. Chronic lymphoedema and angiosarcoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:270–272. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.1999.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudino TA, McKay C, Pendeville-Samain H, Nilsson JA, Maclean KH, White EL, Davis AC, Ihle JN, Cleveland JL. c-Myc is essential for vasculogenesis and angiogenesis during development and tumor progression. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2530–2543. doi: 10.1101/gad.1024602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscolo E, Bischoff J. Vasculogenesis in infantile hemangioma. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:197–207. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9148-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Storer RD, Criswell KA, Doerrer NG, Dellarco VL, Pegg DG, Wojcinski ZW, Malarkey DE, Jacobs AC, Klaunig JE, et al. Hemangiosarcoma in rodents: mode-of-action evaluation and human relevance. Toxicol Sci. 2009;111:4–18. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1345–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Gerald D, Perruzzi CA, Rodriguez-Waitkus P, Enayati L, Krishnan B, Edmonds J, Hochman ML, Lev DC, Phung TL. Vascular tumors have increased p70 S6-kinase activation and are inhibited by topical rapamycin. Lab Invest. 2013;93:1115–1127. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Hashemite N, Walker V, Zhang H, Kwiatkowski DJ. Loss of Tsc1 or Tsc2 induces vascular endothelial growth factor production through mammalian target of rapamycin. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5173–5177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. Vascular tumors and vascular malformations (new issues) Adv Dermatol. 1997;13:375–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjolras O, Wassef M, Chapot R. Color atlas of vascular tumors and vascular malformations. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Foster KG, Fingar DC. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR): conducting the cellular signaling symphony. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14071–14077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.094003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothert JR, Gustin SE, van Eekelen JA, Schmidt U, Hall MA, Jane SM, Green AR, Gottgens B, Izon DJ, Begley CG. Genetically tagging endothelial cells in vivo: bone marrow-derived cells do not contribute to tumor endothelium. Blood. 2004;104:1769–1777. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger S, Bischoff J. Infantile hemangioma-mechanism(s) of drug action on a vascular tumor. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006460. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammill AM, Wentzel M, Gupta A, Nelson S, Lucky A, Elluru R, Dasgupta R, Azizkhan RG, Adams DM. Sirolimus for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1018–1024. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson B, Denekamp J. Endothelial proliferation in tumours and normal tissues: continuous labelling studies. Br J Cancer. 1984;49:405–413. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1984.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu-Lowe DD, Zou HY, Grazzini ML, Hallin ME, Wickman GR, Amundson K, Chen JH, Rewolinski DA, Yamazaki S, Wu EY, et al. Nonclinical antiangiogenesis and antitumor activities of axitinib (AG-013736), an oral, potent, and selective inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases 1, 2, 3. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:7272–7283. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Dibble CC, Matsuzaki M, Manning BD. The TSC1–TSC2 complex is required for proper activation of mTOR complex 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4104–4115. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00289-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng MR, Fuh B, Blatt J, Gupta A, Merrow AC, Hammill A, Adams D. Malignant transformation of infantile hemangioma to angiosarcoma: Response to chemotherapy with bevacizumab. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/pbc.25067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkkainen MJ, Ferrell RE, Lawrence EC, Kimak MA, Levinson KL, McTigue MA, Alitalo K, Finegold DN. Missense mutations interfere with VEGFR-3 signalling in primary lymphoedema. Nat Genet. 2000;25:153–159. doi: 10.1038/75997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ. Rhebbing up mTOR: new insights on TSC1 and TSC2, and the pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis. Cancer Biol Ther. 2003;2:471–476. doi: 10.4161/cbt.2.5.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski DJ, Zhang H, Bandura JL, Heiberger KM, Glogauer M, el-Hashemite N, Onda H. A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex-dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up-regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:525–534. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner H, Karastaneva A, Schwinger W, Benesch M, Sovinz P, Seidel M, Sperl D, Lanz S, Haxhija E, Reiterer F, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of children with various complicated vascular anomalies. Eur J Pediatr. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2572-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech JD, Lammers SH, Goldman S, Auricchio N, Bronson RT, Kwiatkowski DJ, Sahin M. A vascular model of Tsc1 deficiency accelerates renal tumor formation with accompanying hemangiosarcomas. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2015;13:548–555. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohela M, Bry M, Tammela T, Alitalo K. VEGFs and receptors involved in angiogenesis versus lymphangiogenesis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj AS, Saint-Geniez M, Maldonado AE, D'Amore PA. Vascular endothelial growth factor localization in the adult. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:639–648. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankey CC, McHugh JB, Thomas DG, Lucas DR. Can lymphangiosarcoma be resurrected? A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of lymphatic differentiation in 49 angiosarcomas. Histopathology. 2010;56:364–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medici D, Olsen BR. Rapamycin inhibits proliferation of hemangioma endothelial cells by reducing HIF-1-dependent expression of VEGF. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Miettinen M, Wang ZF. Prox1 transcription factor as a marker for vascular tumors-evaluation of 314 vascular endothelial and 1086 nonvascular tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:351–359. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318236c312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner S, Sodhi A, Molinolo A, Bugge TH, Sawai ET, He Y, Li Y, Ray PE, Gutkind JS. Endothelial infection with KSHV genes in vivo reveals that vGPCR initiates Kaposi's sarcomagenesis and can promote the tumorigenic potential of viral latent genes. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:23–36. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner S, Sodhi A, Pece S, Mesri EA, Gutkind JS. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor promotes endothelial cell survival through the activation of Akt/protein kinase B. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2641–2648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onda H, Lueck A, Marks PW, Warren HB, Kwiatkowski DJ. Tsc2(+/−) mice develop tumors in multiple sites that express gelsolin and are influenced by genetic background. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:687–695. doi: 10.1172/JCI7319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S, Tanioka M, Fujisawa A, Tanizaki H, Miyachi Y, Matsumura Y. Angiosarcoma of the scalp successfully treated with a single therapy of sorafenib. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:683–685. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlik TM, Paulino AF, McGinn CJ, Baker LH, Cohen DS, Morris JS, Rees R, Sondak VK. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the scalp: a multidisciplinary approach. Cancer. 2003;98:1716–1726. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phung TL, Ziv K, Dabydeen D, Eyiah-Mensah G, Riveros M, Perruzzi C, Sun J, Monahan-Earley RA, Shiojima I, Nagy JA, et al. Pathological angiogenesis is induced by sustained Akt signaling and inhibited by rapamycin. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitulescu ME, Schmidt I, Benedito R, Adams RH. Inducible gene targeting in the neonatal vasculature and analysis of retinal angiogenesis in mice. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1518–1534. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarmyne MO, Gupta A, Adams DM. Lymphangiosarcoma of the thorax and thoracic vertebrae in a 16-year-old girl. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e294–e298. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou S, Morelon E, Guibaud L, Chotel F, Dijoud F, Marec-Berard P. Efficacy of rapamycin for refractory hemangioendotheliomas in Maffucci's syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e213–e215. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, Fletcher CD. Angiosarcoma arising in hemangioma/vascular malformation: report of four cases and review of the literature. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2002;26:1319–1329. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200210000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi F, Cohen C, Fried L, Arbiser JL. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is activated in cutaneous vascular malformations in vivo. Lymphat Res Biol. 2007;5:233–236. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2007.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi A, Chaisuparat R, Hu J, Ramsdell AK, Manning BD, Sausville EA, Sawai ET, Molinolo A, Gutkind JS, Montaner S. The TSC2/mTOR pathway drives endothelial cell transformation induced by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi A, Montaner S, Patel V, Gomez-Roman JJ, Li Y, Sausville EA, Sawai ET, Gutkind JS. Akt plays a central role in sarcomagenesis induced by Kaposi's sarcoma herpesvirus-encoded G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4821–4826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400835101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallone G, Schena A, Infante B, Di Paolo S, Loverre A, Maggio G, Ranieri E, Gesualdo L, Schena FP, Grandaliano G. Sirolimus for Kaposi's sarcoma in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1317–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang N, Wang L, Esko J, Giordano FJ, Huang Y, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Johnson RS. Loss of HIF-1alpha in endothelial cells disrupts a hypoxia-driven VEGF autocrine loop necessary for tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.