Abstract

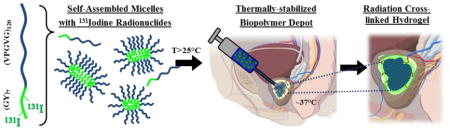

Intratumoral radiation therapy – ‘brachytherapy’ – is a highly effective treatment for solid tumors, particularly prostate cancer. Current titanium seed implants, however, are permanent and are limited in clinical application to indolent malignancies of low- to intermediate-risk. Attempts to develop polymeric alternatives, however, have been plagued by poor retention and off-target toxicity due to degradation. Herein, we report on a new approach whereby thermally sensitive micelles composed of an elastin-like polypeptide (ELP) are labeled with the radionuclide 131I to form an in situ hydrogel that is stabilized by two independent mechanisms: first, body heat triggers the radioactive ELP micelles to rapidly phase transition into an insoluble, viscous coacervate in under 2 minutes; second, the high energy β-emissions of 131I further stabilize the depot by introducing crosslinks within the ELP depot over 24 hours. These injectable brachytherapy hydrogels were used to treat two aggressive orthotopic tumor models in athymic nude mice: a human PC-3M-luc-C6 prostate tumor and a human BxPc3-luc2 pancreatic tumor model. The ELP depots retained greater than 52% and 70% of their radioactivity through 60 days in the prostate and pancreatic tumors with no appreciable radioactive accumulation (≤ 0.1% ID) in off-target tissues after 72 hours. The 131I-ELP depots achieved >95% tumor regression in the prostate tumors (n=8); with a median survival of more than 60 days compared to 12 days for control mice. For the pancreatic tumors, ELP brachytherapy (n=6) induced significant growth inhibition (p = 0.001, ANOVA) and enhanced median survival to 27 days over controls.

Keywords: Elastin-like polypeptide, nanoparticles, hydrogel, radiotherapy, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer

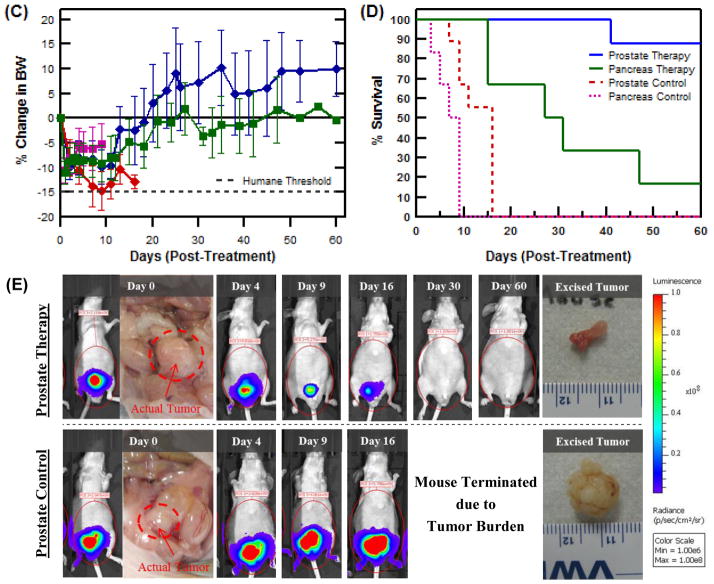

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Brachytherapy — a form of clinical radiation therapy that involves the surgical insertion of titanium ‘seeds’ encapsulating radioactive isotopes to treat tumors from the inside out — has become a widely accepted therapy option for prostate cancer. Over 40% of prostate cancer patients currently receive low dose brachytherapy implants as either a monotherapy or as part of a combination treatment regimen [1]. Multiple studies have found the respective 5-yr and 10-yr recurrence free survival rates for brachytherapy patients to be 91% and 88%, equivalent to patients receiving the ‘gold standard’ of care, surgical prostatectomy [2–8]. Furthermore, brachytherapy can be performed as a 90 minute outpatient procedure without the cost or trauma of surgery [9].

Despite its efficacious track record, medical researchers have consistently sought to develop a polymeric approach for delivering brachytherapy. Titanium seeds, while bioinert, possess several limitations. Current procedures require the placement of 80–120 seeds throughout the tumor via 10–20 separate injections with 17-gauge needles, which require significant surgical skill [10, 11]. The procedure also causes inflammation that can lead to edema that requires catheterization lasting up to 10 days [12]. Improper spatial placement of seeds can also cause the unfortunate side effects of urinary incontinence, sexual discomfort, and seed migration. In addition, studies have shown that dislodged titanium seeds commonly migrate to other organs in the body, although most are safely passed in the urine with discomfort akin to a kidney stone body [13–15]. Finally, titanium seeds remain permanently implanted in the patients after completion of therapy. This has caused patients to note both physical and psychological discomfort long after the seeds’ radioactivity has ceased [16, 17].

A polymeric brachytherapy carrier, capable of in situ self-assembly upon injection, could eliminate many of the complexities and side effects associated with titanium seed implantation. In previous work, our lab developed a biopolymer carrier that utilizes elastin-like polypeptide (ELP) micelles to deliver low energy 125Iodine radionuclides. ELPs are a class of recombinant stimulus responsive polymers that consist of repeats of a pentapeptide sequence — Val-Pro-Gly-Xaa-Gly, where Xaa can be any amino acid except Pro — derived from tropoelastin [18, 19]. The ELP micelles were designed to undergo a thermally triggered lower critical solution temperature, LCST, phase transition at 21°C from a soluble phase into an insoluble, coacervate phase upon in vivo injection [20, 21]. While the design proved to be non-toxic and demonstrated excellent initial retention (~85% after 24 hours), it was susceptible to long term degradation, retaining less than 50% of its injected dose after 7 days. As longitudinal stability is a critical feature for brachytherapy, an improved design of the injectable ELP depot was required.

High energy, ionizing radiation has long been utilized in the synthetic polymer field to induce crosslinking to create hydrogels [22–24]. In the 1970s, radiation was a common method used to investigate polyacrylamide and polyHEMA hydrogel grafts to biomedical implants in order to improve interactions with the host [25]. Urry et al. likewise used 60Co gamma cells to create protein-based hydrogels finding that hydrogel crosslink density and tensile modulus increased with radiation exposure time [26, 27]. Cataldo et al. investigated the composition of covalent crosslinks in mechanically stable hydrogels formed from irradiated collagen and found that 3 major types of covalent crosslinks — disulfide bonds, phenylalanine dimerization, and tyrosine dimerization — were implicated in the radiation crosslinking of collagen [23]. To our knowledge, however, no one has previously attempted to use radiation to crosslink a hydrogel in situ. As our ELP micelle design already incorporated seven tyrosine subunits, (VPGVG)120(GY)7, we hypothesized that it would be similarly amenable to hydrogel crosslinking if a radionuclide with sufficient energy was used.

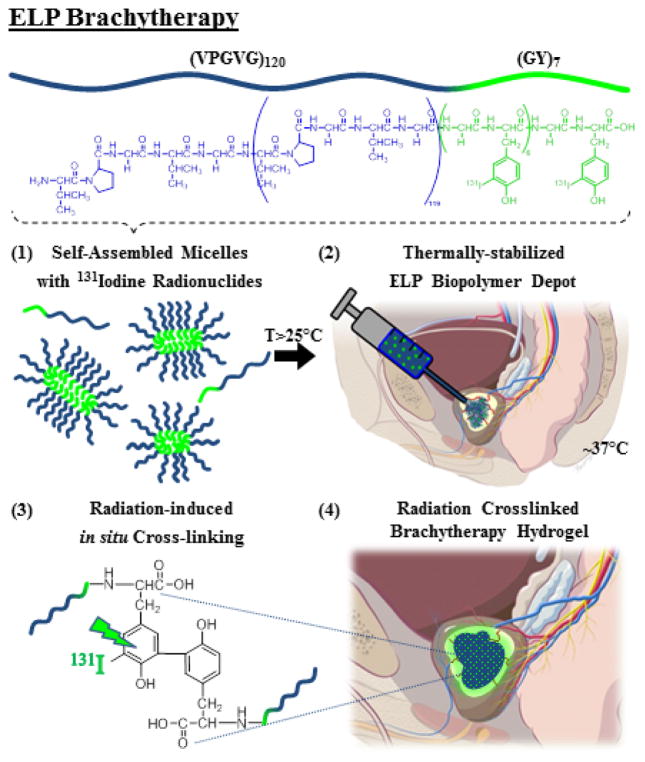

Herein, we report a new strategy whereby the conjugation of the β-radionuclide 131Iodine to a thermally responsive ELP enables a dual mechanism of depot stabilization while simultaneously delivering intratumoral radiotherapy. In this approach, as illustrated in Figure 1, the ELP has a critical micelle temperature (CMT) below room temperature and a micelle-coacervation transition temperature below body temperature. Thus, the depot is initially created when soluble ELP micelles, conjugated to 131I, undergo a soluble-insoluble LCST phase transition in vivo. The viscous coacervate then undergoes further structural stabilization into a hydrogel as the 131I emits high energy beta particles that induce covalent crosslinking within 24 hours.

Figure 1.

Design and mechanism of ELP brachytherapy depot formation.

We chose to inject I-ELP conjugates in the form of micelles, rather than unimers – individual polymer chains– because we have shown that the ELP micelle-coacervate phase transition is independent of concentration as compared to the ELP unimer. This provides two major advantages: (1) it provides a large window of concentration for treatment planning, and (2) the micelle-to-coacervate transition is far less sensitive to in vivo dilution than a unimer-to-coacervate design, minimizing the loss of ELP prior to radiation crosslink mediated stabilization of the brachytherapy depot.

To test the stability and therapeutic effectiveness of this strategy, 131I-ELP brachytherapy depots were used to treat two aggressive orthotopic tumors in athymic mice – PC-3M-luc-C6 human prostate cancer and BxPc3-luc2 human pancreatic cancer. Orthotopic tumor models were chosen as they more closely mimic the clinical presentation of cancer in humans. It also enabled assessment of depot stability and radiation spillover effects to neighboring organs in a clinically relevant biochemical and anatomical microenvironment as compared to the s.c. environment of our previous study that is far more tolerant to high dose radiation [21]. The in vivo results demonstrate the clinical utility of ELP β-brachytherapy and highlight its potential advantages compared to standard clinical low dose brachytherapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. ELP synthesis and radiolabeling

An ELP with the sequence, (VPGVG)120(GY)7, was recombinantly synthesized by overexpression of a synthetic gene encoding the ELP in a pET-24a+ expression vector (Novagen Inc., Madison, Wi) in BLR(DE3) competent E. coli (Edge BioSystems, Gaithersburg, MD) using previously published methods [21, 28]. A summary of the molecular biology methods used for ELP genetic expression, synthesis, and purification can be found in the Supplemental Materials. Radionuclide labeling, for both 125I and 131I, was performed using the iodogen oxidative reaction method [29]. Na125I and Na131I were purchased from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA) and reacted with 500 μM ELP in Pierce® pre-coated IODOGEN tubes (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) on ice for 30 min. The product was purified by centrifugal ultrafiltration using 40K molecular weight cut off (MWCO) Zeba Spin Desalting Columns (ThermoScientific, Rockford, IL) at 2500 rpm for 3 min at 4°C to remove any unreacted radioiodine. The desired concentration of ELP was obtained by mixing the reaction product with unlabeled ELP to bring the final concentration of ELP to 1000 μM. Radioactivity was measured using the AtomLab 400 dose calibrator (Biodex, Shirley, NY).

2.2. Characterization of ELP properties

The thermal properties of the ELP were characterized by measuring solution turbidity as a function of temperature on a multi-well Cary 300 UV-vis spectrophotometer (Varian Instruments, Palo Alta, CA). The optical density was measured at 350 nm as a function of temperature. The temperature was raised from 15°C to 45°C at a rate of 1°C/min, with absorbance readings measured every 0.3°C. The TT was defined as the temperature at which the first derivative of absorbance with respect to temperature was maximized. The macroscopic kinetics of phase separation were determined by setting the block temperature to 37°C and rapidly inserting an ELP sample, in a cuvette stored at 4°C, into the spectrophotometer. Absorbance readings at 350nm were measured every 0.1seconds for up to 10 minutes. For DLS and SLS particle sizing, samples were sterile filtered using a 200nm filter in PBS. Samples were first measured on a DynaPro Plate Reader (Wyatt Technology) for DLS and then an ALV/CGS-3 Compact Goniometer System (ALV-GmbH, Langen, Germany) for SLS analysis.

2.3. Establishing orthotopic xenograft models

Bioware® PC-3M-luc-C6 and BxPc3-luc2 cell lines were purchased from PerkinElmer (Hopkinton, MA). Both cell lines were authenticated with STR-DNA technology (RADIL) by DUCCF and Caliper Life Science. They were independently verified to be pathogen free following IMPACT III murine pathogen analysis by IDEXX BioResearch (Columbia, MO). The PC-3M-luc-C6 cells were cultured in Gibco MEM media (Invitrogen #11095, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with Earle’s salts, L-glutamine, 10% HI-FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (10000/10000 per ml), 0.1mM non-essential amino acids, and 1mM sodium pyruvate [30]. BxPc3-luc2 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media (Invitrogen #11875, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% HI-FBS [31, 32]. Cells were incubated and grown as monolayers at 37°C and 5% CO2. At 80% confluence, cells were trypsinized and collected. PC-3M-luc-C6 cells were suspended in DMEM at a 1×105 cells/μl ratio while BxPc3-luc2 cells were suspended in 1×105 cells/μl of Matrigel®. All cells were cryopreserved and maintained to not exceed 30 passages or 6 months from time of authentication.

Six-week old athymic Balb/c nude male mice were ordered from the Duke University Immunoincompetent Rodent and Biohazard Facility and housed in the Duke Cancer Center Isolation Facility. The mice received intraperitoneal ketamine/xylazine anesthesia injections, were sterilized with 75% ethanol, and fixed on a heated surgical board. The organ of interest was accessed using 1 cm midline incisions through the abdomen and peritoneal membrane. For the prostate model, 10 μl of a PC-3M-luc-C6 cell suspension was injected into the right dorsolateral prostate lobe. For the orthotopic pancreas model, a looped strand of 5-0 absorbable suture was used to cinch a portion of the pancreatic tissue to provide an injection site [33]. 10 μl of the BxPc3-luc2 cell solution was then injected. The membrane and abdomen were both closed using absorbable 5-0 sutures. Triple antibiotic ointment was applied to the closure site and buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg) was injected s.c. for pain management. Mice were monitored daily for any resulting complications.

2.4. Measuring stability and efficacy of 131I-ELP brachytherapy depots

After initial tumor cell inoculation, tumors were allowed to grow for 3–4 weeks, depending on tumor type, to achieve a volume between 90–120 mm3. Their drinking water was prophylactically supplemented with 0.4g of KI per 100 ml to inhibit potential radioiodine uptake by the thyroid during treatment. For PC-3M-luc-C6 prostate tumors, n=20 mice were inoculated and tumors grown for 21 days. For BxPc3-luc2 pancreatic tumors, n =20 mice were inoculated and tumors grown for 25–28 days. Mice with tumors over 200 mm3 or that had formed metastases were excluded from the study. The remaining mice were randomized into 2 experimental arms for each tumor type. Due to complexity and duration of surgeries, prostate and pancreatic preclinical trials were conducted separately.

To perform brachytherapy injections, tumors were accessed via a second survival. The 131I-ELP was administered at 1000 μM and a volume fraction of 1/3 the tumor size. For the prostate tumor group, eight mice received 131I-ELP injections at 10 μCi/mm3, while nine mice received control injections of unlabeled ELP. For the pancreatic tumor radiotherapy, six mice were intratumorally injected with the 131I-ELP conjugate at a target activity concentration of 5.5μCi/mm3, while six mice received ELP-only control injections. The 131I-ELP was infused through a 27 ½ gauge microsyringe using a motorized pump maintained on ice at a rate of 120 μl/min. Mice were housed in cages behind lead safety barriers following the guidelines of the Duke OESO – Radiation Safety Division and monitored daily for 1 week. Body weight, radioactivity levels, signs of infection, urinary complications and other morbidity symptoms were all tracked for sixty days. Total body radioactivity for each mouse was measured 2–3 times a week using an AtomLab 400 dose calibrator. Tumor response was measured non-invasively 2–3 times a week by quantifying total tumor luminescence and normalizing it to signal the signal intensity at day 0 of treatment. Mice experiencing either a sustained weight loss of more than 15% or greater than 5-fold tumor enlargement were euthanized in accordance with Duke DLAR, the American Veterinary Medical Association, and NIH policies [34, 35]. Upon completion of the experiment, all prostate tumors were excised and sent to the Department of Pathology at the Duke University Medical Center for histological preparation and analysis. Radioactive waste, bedding, and carcasses were disposed of in accordance with Duke Radiation Safety Division guidelines.

2.5. Biodistribution study of 125I-ELP depot

Mice were orthotopically inoculated with PC-3M-luc-C6 prostate tumors. Tumors were grown for 21 days to mimic therapy conditions. ELP was purified and labeled with 125I at a dose of 0.15 μCi/μl of ELP. In a second surgical procedure, it was injected into the core of each tumor at a concentration of 1000 μM and volume of 20 μl per 150 mm3 of tumor. The whole body radioactivity level in the mouse was measured upon closure to determine the injected dose. 125I-ELP samples were aliquoted at different volumes, in triplicate, to create a set of standards ranging in activity from 0–30 μCi, as measured using the AtomLab 400 dose calibrator. Mice were randomized into four groups (n = 6) to assess the biodistribution of ELP at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. At the specified time point, each mouse was anesthetized and 100 μl of blood was drawn from the ocular sinus. They were then euthanized and dissected to collect the skin, muscle, thyroid, heart, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, stomach, small intestines, large intestines, rectum, prostate tumor, bladder, seminal vesicles, coagulating glands, preputial glands, and testes. Each tissue was counted for 125I activity using a Wallac 1282 Gamma Counter (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) in counts per minute (CPM). Relative retention of 125I-ELP for each tissue was compared using the CPM values. The percent injected dose (%ID) was computed using the standard curve to relate CPM to μCi and then compared against the whole body injected dose.

3. Results

Characterizing the thermal responsiveness and kinetics of ELP depot formation

The underlying premise of the 131I-ELP brachytherapy depot involves coupling two complementary stabilization mechanisms. Ionizing radiation can form mechanically stable hydrogels, but require a time scale of 12–48 hours to properly cure [23]. Initial convective forces upon injection, the high interstitial fluid pressure of tumors, and molecular diffusion all cause soluble polymers to rapidly disseminate out of the tumor microenvironment long before a hydrogel can form. To address this problem, the ELP ensures immediate in situ self-assembly of the depot within the tumor and maintains its stability until the material has enough time to form a radiation crosslinked hydrogel.

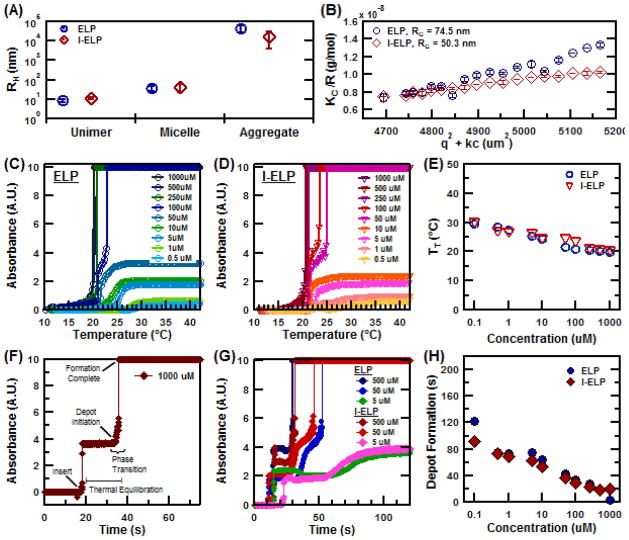

With these considerations in mind, we chose to inject radioactive ELP micelles rather than radioactive ELP unimers because ELP micelles have a largely invariant micelle-coacervate TT over a wide range of concentrations [28, 36]. Micelle assembly can be programmed into an ELP by simply incorporating a hydrophobic tail domain at the C-terminus of an ELP. We selected a (GY)7 tail for two reasons: (1) this hydrophobic motif drives self-assembly of ELPs into rod-shaped micelles [36]; and (2) the tyrosine residues conveniently provide conjugation sites for iodine coupling through the IODOGEN reaction method [29]. Because the conjugation of iodine may potentially alter self-assembly and material properties, the ELP nanoparticles were characterized before and after chemical conjugation in order to investigate the effects of iodination on micelle size and thermal responsiveness (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Material properties of unmodified and Iodine-labeled ELP nanoparticles. (A) Hydrodynamic radius (RH). (B) Radius of gyration (RG). (C) Turbidity profile of ELP and (D) Iodine-labeled ELP as a function of solution temperature. (E) Concentration dependence of the TT for ELP and I-ELP. (F) Representative kinetic transition profile for ELP as a function time. (G) Transition kinetics data for dilutions of ELP and I-ELP at 37°C. (H) Concentration dependence of depot formation time for both ELP and I-ELP.

Micelle formation was characterized by dynamic and static light scattering (DLS and SLS, respectively) at 15°C. DLS indicated that ELP unimers had a hydrodynamic radius (RH) of 8.6 ±1.5nm and formed micelles with a RH of 34.4 ±11.1nm (Figure 2A). A small, residual population of unimers was present in solution after micelle formation. Iodine conjugation was carried out under the same reaction conditions and concentration used during radionuclide labeling, albeit with non-radioactive NaI. The I-ELP micelle RH was 41.2 ±18.6nm. SLS analysis confirmed the radius of gyration, RG of ELP micelles was 74.5 nm while that of I-ELP micelles was 50.3 nm. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry analysis revealed that the ratio of conjugated iodine was 3.7 per ELP molecule (Suppl. Materials).

The TT of the micelle-coacervate transition for ELP and I-ELP nanoparticles were next characterized to verify their ability to assemble into depots at body temperature. As shown in Figure 2C–E, the phase transition occurred well below physiological body temperature for ELP concentrations spanning 0.1–1000 μM. At the planned injection concentration of 1000 μM, the ELP exhibited a TT of 20.5ºC while that of I-ELP was 19.8ºC. The TT of both ELP and I-ELP micelles were relatively insensitive to concentration changes, which is consistent with previous results for ELP micelles [28]. The kinetics of coacervate formation was investigated using a temperature jump experiment to simulate ELP injection at body temperature. Briefly, ELP and I-ELP solutions at various concentrations were stored at 4°C. They were then inserted into a 37°C pre-heated UV-vis spectrophotometer and the corresponding change in absorbance was measured as the solution was heated. A typical turbidity profile, with events clearly marked, is shown for a reference solution of ELP at 1000 μM (Figure 2F). The standard profile demonstrates an initial time lag between insertion of the cuvette and the onset of the phase transition. This duration, denoted ‘thermal equilibration’, is dictated by the heat transfer properties of the quartz cuvettes as the sample equilibrates to the spectrophotometer bulk temperature of 37°C. This equilibration duration accounts for a majority of the time required for in vitro depot formation and is highly influenced by the thermal conductivity of the quartz. Even for dilutions as low as 0.1 μM, the equilibration lag time remained similar to ELP solutions at much higher concentrations. Depot formation consistently occurred in less than two minutes of spectrophotometer insertion for both ELP and I-ELP (Fig. G, H). In vivo, however, the injected ELP solution will be directly in contact with tissue at 37°C. This would eliminate the time lag due to the heat transfer through the quartz. Presumably, the kinetics of I-ELP depot formation would then be even more rapid upon intratumoral injection.

Intratumoral stability and biodistribution of 131I-ELP depots

We next investigated the ability of 131I radiation to crosslink and stabilize the depot. 131I-ELP was prepared at a therapeutic dose of 10μCi/μL, and 100μL samples (n=5) were injected into Eppendorf tubes and incubated at 37°C. The ability of ELP to form stable depots could then be tracked by measuring the fraction of radioactivity retained in the insoluble coacervate when separated from the liquid phase.

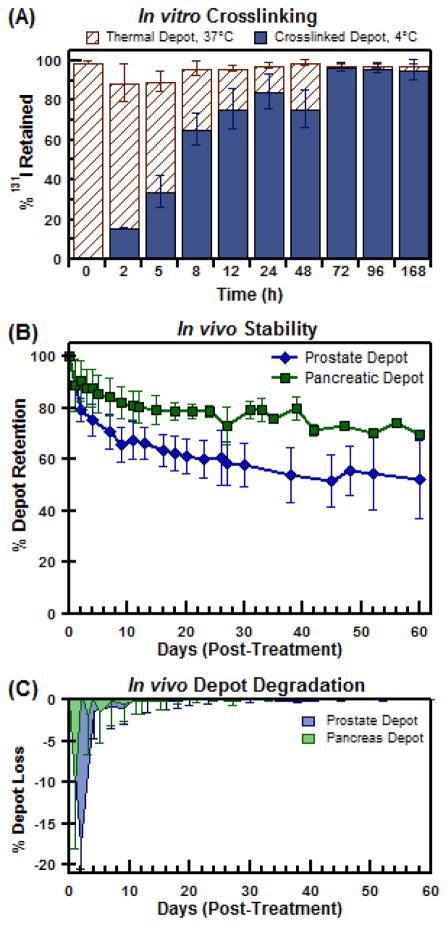

At 37°C, thermally-stabilized ELP depots were found to always retain greater than 96.5% of the total solution radioactivity (Figure 3A). This re-affirmed that ELP micelles self-assembled into highly retentive depots when carrying a radioactive payload. It also provided a benchmark to determine the progression of depot crosslinking. Since the ELP phase transition is reversible, the thermal depots completely resolubilize when cooled at 4°C for 15 minutes. When ELP molecules become physically crosslinked in the coacervate phase, however, they become irreversibly insoluble. By separating the insoluble and liquid phases after cooling to 4°C, the fraction of radioactivity retained by the insoluble depot can be used to measure the relative conversion of the thermal depot into a crosslinked hydrogel.

Figure 3.

In vitro and in vivo stability of injectable 131I-ELP depots (A) Insoluble depot retention of 131I radioactivity at 37°C and 4°C; tracking the extent of depot crosslinking over exposure time. (B) In vivo radioactivity retention of 131I-ELP brachytherapy depots in orthotopic mouse prostate (PC-3M-luc-C6) and pancreatic (BxPc3-luc2) tumor models after accounting for isotopic decay. (C) Percent loss of depot payload due to depot degradation over time.

As Figure 3A shows, prolonged radiation exposure of the thermal depot causes an increasing fraction of ELP to permanently remain in depot form. At t=0 hours, no observable depot could be measured or detected. This was consistent with the normal behavior of unlabeled ELP. For t < 5 hours, the majority of the depot was found to resolubilize back into solution, but a small fraction of depot was found to be irreversible. It is apparent that radiation induced crosslinking had begun, but had yet to stabilize the coacervate in a meaningful manner. From 24 hours onwards, though, the extent of crosslinking had progressed to fully stabilize the 131I payload as a permanent depot. Thus, it was confirmed that 131I-ELP could induce crosslinking to provide a dual mechanism of depot stability for biopolymer brachytherapy.

Intratumoral retention of the 131I-ELP depots were next evaluated in vivo in an orthotopic prostate (n=8) and orthotopic pancreas (n=6) tumor model (Figure 3B). The radioactivity profiles of the depots were normalized to the physical decay of 131I, t1/2 = 8.03 days, to generate the retention profile within each tumor. By fitting the radioactivity profiles as an exponential decay function, the effective half-life of the prostate and pancreas brachytherapy depots were determined to be 7.14 ± 0.17 days and 7.51 ±0.04 days, respectively. The data sets also provided useful insights into the modes of loss of radioactivity of the 131I-ELP depot. In both models, the majority of the radioactivity loss occurred after injection during the initial 24 hour window (Figure 3C). Depots implanted in prostate tumors (n=8) experienced a bolus loss of 17.7 ± 2.8% while those implanted in pancreatic tumors (n=6) saw a 10.5 ± 7.5% loss of 131I-ELP immediately after injection. After 24 hours, though, the depots exhibited significantly stronger retention and minimal loss. The effective rate of loss of radioactivity from the prostate tumor depot was 1.08 ±0.20% per day during the first week (Figure 3C). Over the same time period, depots in the pancreatic tumor lost radioactivity at a rate of 0.51 ±1.15% per day during the same time period. After 9 days, however, both depots showed a similar loss rate of 0.05 ±0.15% per day. Upon completion of treatment at day 60, the prostate depots retained 52.4 ±7.1% of their radioactive payload while the pancreatic depots retained 69.8 ±1.1% their payload.

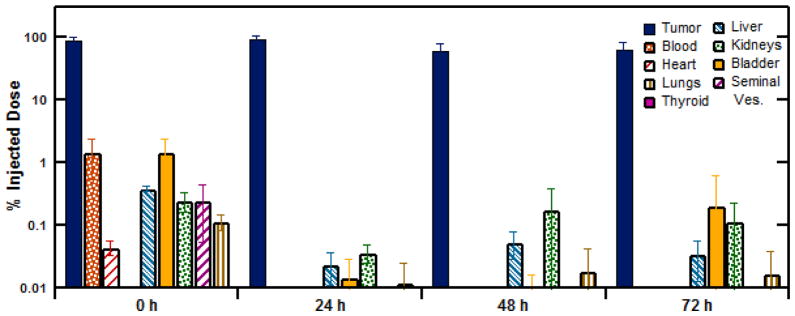

The potential toxicity of the ELP brachytherapy to normal tissues was next investigated by measuring the radioactivity from 19 organs by tissue necropsy. The tissues were individually collected and measured for radioiodine accumulation at time points of 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. Figure 4A shows the tumor-specific depot retention as measured by the percentage of 125I activity in the excised tumor compared to the whole mouse radioactivity. Immediately after injection, only 88.8 ±4.9% of the 125I-ELP signal was found within the prostate tumor (n=6), confirming that a tenth of the injected ELP dose was lost before it thermally transitioned in situ into an insoluble depot. For t≥24h, the prostate tumor accounted for 98.7 ±1.3% of radioactivity in the body, indicating that (1) the radioactivity initially lost during the injection was not retained within the body of the mouse and (2) that the retained radioactivity was all contained within the tumor. This confirmed the successful formation of a stable radioactive depot. Gamma radiation counting further corroborated this observation by quantifying the dissemination of 125I-ELP to off-target tissues. Figure 4B shows the results from a subset of tissues of particular interest, with all tissue results provided in the Supplemental Materials.

Figure 4.

Biodistribution study assessing the dissemination of radionuclide-labeled ELP depots and potential side effects in off-target tissues. 125I-ELP accumulation, correct for isotope decay, in each tissue is shown as the percent injected dose (%ID).

The highest % ID off-target accumulation of 125I-ELP occurred immediately after injection, and was observed in the blood (1.44 ± 0.75%), bladder (1.47 ± 0.90%), large intestines (1.24 ± 1.98%), and skin (1.15 ± 0.36%). After 24 h, radioactivity levels in these tissues diminished significantly (p < 0.05, Student t-test) to less than 0.1% ID and remained at this level at 48 and 72 h. The thyroid, the primary site of iodide accumulation in the body, exhibited less than 0.005% ID at each time point, suggesting that the ELP construct was resistant to dehalogenation in vivo. Normal organs, such as the heart and lung, demonstrated extremely low accumulation levels of less than 0.02% from 24 h onwards. This behavior was observed in the systemic tissues as well as proximal reproductive tissues, such as the seminal vesicles, coagulating glands and testes. The organs displaying the highest accumulation of 125I-ELP past 24 h were the kidneys and bladder. However, even these organs displayed levels of 125I activity less than 0.20 ±0.41 % ID. Taken in context, this suggests that the fraction of ELP initially lost during the injection is cleared relatively quickly from the body. Moreover, negligible radiotoxicity should be expected due to the low degree of ELP dissemination and accumulation in normal tissues.

Efficacy of 131I-ELP brachytherapy in orthotopic tumor models

While the previous results reported herein explored the ability of 131I to self-stabilize ELP depots by inducing radiation crosslinking of the polypeptides, the radionuclide also served the dual role as the effective brachytherapy agent. The orthotopic PC-3M-luc-C6 prostate tumor model was the first model we investigated to assess the efficacy of ELP-based brachytherapy. The treatment group (n=8) averaged an initial tumor size of 99.6 ± 25.5 mm3, statistically equivalent to the control group (n=9) size of 119.3 ± 62.9 mm3 (p = 0.41, Student t-test). Mice in the treatment arm were administered 131I-ELP with a radioactivity dose of 11.82 ±4.01 μCi per mm3 of tumor at an injection concentration of 1000 μM ELP. The bolus injection volume of ELP was 1/3 the tumor size and delivered as a single, focal infusion into the tumor core. Control mice received similar injections of an unlabeled ELP at the same concentration. All mice and tumor responses were monitored for 60 days.

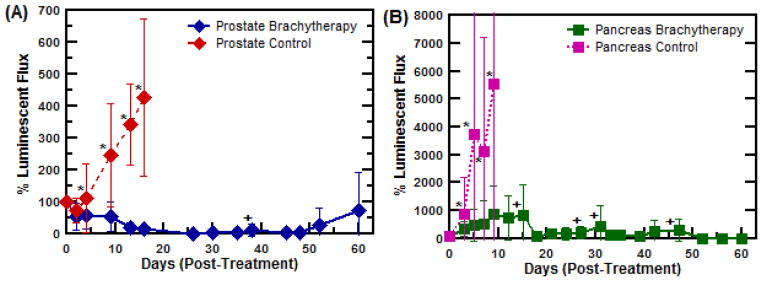

A second pancreatic tumor model comprising the cell line BxPc3-luc2 was similarly used to examine the advantages of ELP-based brachytherapy with a tumor type that is highly resistant to both radiation and chemotherapy, providing a more stringent challenge for 131I-ELP brachytherapy. [30, 31]. Due to heightened concerns of radiation exposure of vital organs, a 2-fold lower radiation dose of 5.83 ± 0.57 μCi/mm3 of tumor – compared to the prostate brachytherapy – was administered to the treatment group. Subsequent tumor responses for both models were tracked by monitoring the corresponding tumor luminescence and normalizing it to signal from the tumor prior to treatment (Figure 5A and 5B).

Figure 5.

Preclinical efficacy trial of ELP brachytherapy for the treatment of orthotopic, human PC-3M-luc-C6 prostate tumor xenografts in athymic, nude mice. (A) Average PC-3M-luc-C6 prostate tumor size following 131I-ELP therapy (n=8) or control ELP injections (n=9). *,+ indicate when mouse numbers are reduced in each respective group. (B) Average BxPc3-luc2 pancreatic tumor size upon receiving 131I-ELP therapy (n=6) or control ELP-only injections (n=6). (C) Percent body weight change during treatment; and (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all treatment groups over the 60 day time frame. ELP brachytherapy was found to confer significant survival benefit over the control group in both models (p<0.001, log-rank test). (E) Visual and luminescent imaging sequence showing the progression of tumors treated with ELP brachytherapy versus ELP control injections.

The response of the PC-3M-luc-C6 prostate tumors to 131I-ELP brachytherapy was dramatic. Significant tumor regression was achieved within 9 days relative to the control group (p = 0.0001 ANOVA) and all treated tumors were reduced to less than 5% of their original size within 26 days (Figure 5A). Upon completion of the study after 60 days, 4 of the 8 treated mice remained tumor free (Supplemental Materials). One mouse experienced metastatic growth and was euthanized at day 41; however, its primary tumor was less than 32% of its initial size at that time. The three other treated mice experienced variable degrees of primary tumor relapse over the duration of the study.

The response of the pancreatic BxPc3-luc tumors was likewise striking, exhibiting significant tumor inhibition after 7 days (p = 0.013, ANOVA) (Figure 5B). The control mice in both models demonstrated rampant tumor growth taken after just one week, while 4 of the 6 treated tumors remained under 300 mm3 upon completion of the experiment (Supplemental Materials). Individual mouse data is provided in the Supplemental Materials.

Radiotoxic side-effects were not observed in the either set of treated mice, as monitored by change in body weight in Figure 5C. Indeed, no statistical difference in body weight loss was observed in brachytherapy treated mice compared to controls (p > 0.280 ANOVA). Instead, an initial drop in body weight was seen across all experimental groups due to surgery, but treatment groups quickly regained their original weight. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves in Figure 5D show that the median survival for mice with prostate tumors receiving ELP-only control injections was 13 days. In contrast, 87.5% of ELP brachytherapy mice survived through 60 days (p = 0.0001, log-rank test), at which point they were euthanized. Similar to the prostate tumor therapy experiment, ELP brachytherapy conferred significant survival benefit to treated mice with pancreatic tumors (p = 0.0011, log-rank test). Despite these positive metrics, no mouse achieved complete tumor remission over the course of treatment. Only 1 mouse remained alive at 60 d. A timeline of the representative response of a prostate tumor to 131I-ELP brachytherapy can be visualized in Figure 5E, including luminescence imaging and ex vivo size comparisons. A similar timeline for pancreatic tumors are included in the Supplementary Materials. A full comparison of the results from both tumor models is summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Summary of Brachytherapy Trials for Orthotopic Prostate & Pancreatic Tumors in Mice.

| Prostate (PC-3M-luc-C6) | Pancreas (BxPc3-luc2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brachytherapy Depot | Control Group | Brachytherapy Depot | Control Group | |

| # Mice: | 8 | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Body Weight: | 27.2 ± 2.1 g | 28.8 ± 2.7 g | 29.4 ± 1.8g | 29.0 ± 2.4g |

| Tumor Size: | 99.6 ± 25.6 mm3 | 119.3 ± 62.9 mm3 | 155.2 ± 42.4 mm3 | 130.9 ± 37.2 mm3 |

| 131I Dose: | 11.8 ± 4.0 μCi/mm3 | 0 μCi/mm3 | 5.8 ± 0.6 μCi/mm3 | 0 μCi/mm3 |

| Avg. ELP Vol: | 36.6 ± 8.7 μl | 33.7 ± 17.8 μl | 54.5 ± 18.7 μl | 53.2 ± 9.9 μl |

| Terminal Size: | 6.1 ± 9.8%† | 425.5 ± 246.6%† | 203.5 ± 112.7%* | 375.9 ± 180.4%* |

| Median Survival: | 60+ days† | 12 days† | 27 days† | 7 days† |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.005, unpaired t-test.

4. Discussion

Brachytherapy is a powerful technique for the treatment of solid tumors as it localizes the effective biological dose delivered to a tumor while simultaneously lowering the total amount of radiation a patient receives. Simultaneously, it limits the exposure of healthy tissue to radiation. Our results suggest that injectable ELP depots could provide a better alternative to current titanium seed brachytherapy technology for several reasons. From a materials perspective, it provides a non-permanent alternative for delivering treatment that is biodegradable into non-toxic amino acids. The size and number of injections required could also be reduced, diminishing the severity of inflammation, a common side effect caused by the surgical implantation of multiple seeds. Complications arising from seed migration would also be eliminated. The ability to handle ELP as a liquid solution should also simplify the technical difficulty of the injection procedure. Finally, ELPs can be chemically conjugated to a broader range of radionuclides to tailor the therapy according to specific tumor types and anatomical sites.

Titanium ‘seeds’ are also limited to the use of encapsulated 125I, 103Pd, or 131Cs radionuclides. The half-life of each isotope is 59.4 d, 17.0 d, and 9.7 d with average gamma ray energies of 28.5 keV, 20.8 keV, and 30.4 keV, respectively [12, 37]. While the titanium casing renders the seeds bio-compatible, it also inhibits the transmission of most radiation particles other than gamma photons. Hence, only low-energy gamma rays can be employed with permanently implanted seeds, which penetrate up to 1.5 cm in soft tissue [38]. In contrast, the ability to chemically conjugate ELP with radionuclides allows for the delivery of radionuclides that provide more potent therapeutic effects. To leverage these advantages, we selected the beta-particle emitter 131I for ELP-based brachytherapy. Beta particles are preferable for several reasons. First, 131I β-particles deliver a higher average energy of 181.9 keV and are capable of treating aggressive forms of cancer [39]. Second, beta emissions only penetrate up to 2 mm through soft tissue, thus reducing off-target irradiation of healthy tissues. Third, 131I also has a half-life of 8.02 days, which diminishes the radiation exposure time for patients. This is a highly desirable feature for patients when compared with the 59.4 day half-life of 125I, the predominant clinical isotope used for gamma radiation based brachytherapy [38]. Finally, ionized electrons at this energy can oxidize the phenol moiety of tyrosine, serving the dual role of inducing hydrogel crosslinking.

Many hydrogel systems, based on both synthetic polymers and natural biopolymers, have previously explored the use of thermosensitive assembly to form in situ depots. However, all systems ultimately suffer from a lack of longitudinal retention (< 50% ID after 7 days), which is not acceptable for the safe delivery of radionuclides [20, 40–42]. As our results show, the design of the 131I-ELP system overcomes this limitation by strategically combining two mechanisms of depot stabilization that temporally complement each other. The resulting depots demonstrated durable stability in both the prostate and pancreas, despite the different anatomical, structural and biochemical microenvironments of these two tumor types. A slow rate of depot degradation was observed, but not to an extent that would jeopardize its stability during the duration of treatment. In fact, improved injection strategies should further reduce the only appreciable source of ELP loss: the initial injection. Adjusting the speed, size, and location of injections should reduce the intratumoral pressure that can cause leakage of soluble ELP during injection. The negligible off-target accumulation of radioactivity, coupled with the lack of systemic side-effects in both therapies, suggest that any ELP that does escape the tumor is safely cleared from the body.

The therapeutic benefits of 131Iodine for delivering β-brachytherapy are clearly evident in both tumor models. The PC-3M-luc-C6 model provided a relevant test to evaluate translational potential of this technology. The prostate model results are particularly promising because all mice experienced over 95% tumor regression and 4 remained in full remission at the end of the 60 day observation period. Although pancreatic cancer is not commonly treated with brachytherapy, its dismal prognosis has stimulated new trials investigating neo-adjuvant and adjuvant options that could improve surgical outcomes [43–45]. In this context, the 131I-ELP displays promising potential against the radiation resistant BxPc3-luc2 pancreatic tumor in a completely novel application of brachytherapy. Subsequent optimization of both the amount and spatial distribution of the radiation dose could result in better tumor inhibition and remission.

The self-stabilizing design and anti-tumor efficacy of the 131I-ELP brachytherapy depots overcome many of the limitations associated with thermosensitive radionuclide polymer depots while extending the possible applications of brachytherapy. Further work exploring the spatial distribution of the ELP, and corresponding radiation dosimetry, must be explored to ensure complete tumor coverage. As is apparent from the histology analysis, incomplete coverage is a potential limitation of the bolus administration of the ELP depot. Further development of physical dosimetry models and intratumoral pre-planning techniques could alleviate these concerns. Other options for enhancing coverage at the tumor margins could include the co-injection of another ELP-radionuclide conjugate a longer penetrating radionuclide, such as 125Iodine. The complementary low-energy dose deposition profile could irradiate the tumor margins that might otherwise escape the shorter penetrating β-emissions of 131I. Synergistic depot therapies could also be developed that employ radiation sensitizers or chemotherapy agents. Each could increase the potency of the therapy while reducing the radiation exposure of normal tissues and consequent side effects experienced by the patient. In conclusion, these pre-clinical results validate the strategy of using dual stabilized 131I- ELP depots for the safe and effective brachytherapy of multiple types of solid tumor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The ELP molecule was originally designed by Jonathan R. McDaniels. This work was supported by NIH grant 5R01CA138784-03 and a seed grant P30CA014236 from the Duke Cancer Institute to W.L. and NIH grants R01EB000188 and R01EB007205 to A.C.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Ashutosh Chilkoti is a Scientific Advisor and is on the Board of Directors of PhaseBio Pharmaceuticals, which has licensed the ELP technology from Duke University.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sharkey J. Trends in prostate brachytherapy. Sixth Annual Advanced Prostate Brachytherapy Conference; Seattle, WA. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tward JD, Lee CM, Pappas LM, Szabo A, Gaffney DK, Shrieve DC. Survival of men with clinically localized prostate cancer treated with prostatectomy, brachytherapy, or no definitive treatment: impact of age at diagnosis. Cancer. 2006;107:2392–2400. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vicini FA, Martinez A, Hanks G, Hanlon A, Miles B, Kernan K, Beyers D, Ragde H, Forman J, Fontanesi J, Kestin L, Kovacs G, Denis L, Slawin K, Scardino P. An interinstitutional and interspecialty comparison of treatment outcome data for patients with prostate carcinoma based on predefined prognostic categories and minimum follow-up. Cancer. 2002;95:2126–2135. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giberti C, Chiono L, Gallo F, Schenone M, Gastaldi E. Radical retropubic prostatectomy versus brachytherapy for low-risk prostatic cancer: a prospective study. World J Urol. 2009;27:607–612. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kupelian PA, Potters L, Khuntia D, Ciezki JP, Reddy CA, Reuther AM, Carlson TP, Klein EA. Radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy <72 Gy, external beam radiotherapy > or =72 Gy, permanent seed implantation, or combined seeds/external beam radiotherapy for stage T1–T2 prostate cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2004;58:25–33. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potters L, Klein EA, Kattan MW, Reddy CA, Ciezki JP, Reuther AM, Kupelian PA. Monotherapy for stage T1–T2 prostate cancer: radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, or permanent seed implantation. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2004;71:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potters L, Morgenstern C, Calugaru E, Fearn P, Jassal A, Presser J, Mullen E. 12-year outcomes following permanent prostate brachytherapy in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. The Journal of urology. 2008;179:S20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sylvester JBJE, Grimm R, Meier R, Spiegel JF, Malmgren JA. Fifteen year follow-up of the first cohort of localized prostate cancer patients treated with brachytherapy. 2004 ASCO Anual Meeting, Journal of Clinical Oncology; Seattle, WA. 2004. p. 4567. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grimm P, Sylvester J. Advances in Brachytherapy. Reviews in Urology. 2004;6:S37–S48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holm HH, Juul N, Pedersen JF, Hansen H, Stroyer I. Transperineal 125iodine seed implantation in prostatic cancer guided by transrectal ultrasonography. The Journal of urology. 1983;130:283–286. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)51108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blasko HRJC, Schumacher D. Transperineal percutaneous iodine-125 implantation for prostatic carcinoma using transrectal ultrasound and template guidance. Endocurietherapy/Hyperthermia Oncology. 1987;3:9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waterman FM, Yue N, Corn BW, Dicker AP. Edema associated with I-125 or Pd-103 prostate brachytherapy and its impact on post-implant dosimetry: an analysis based on serial CT acquisition. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1998;41:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merrick GS, Butler WM, Dorsey AT, Lief JH, Benson ML. Seed fixity in the prostate/periprostatic region following brachytherapy. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2000;46:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hathout L, Donath D, Moumdjian C, Tetreault-Laflamme A, Larouche R, Beliveau-Nadeau D, Hervieux Y, Taussky D. Analysis of seed loss and pulmonary seed migration in patients treated with virtual needle guidance and robotic seed delivery. American journal of clinical oncology. 2011;34:449–453. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181ec63c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stutz M, Petrikas J, Raslowsky M, Lee P, Gurel M, Moran B. Seed loss through the urinary tract after prostate brachytherapy: examining the role of cystoscopy and urine straining post implant. Medical physics. 2003;30:2695–2698. doi: 10.1118/1.1604491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stock R, Kao J, Stone N. Penile erectile function after permanent raioactive seed implantation for treatment of prostate cancer. The Journal of urology. 2001;165:436–439. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potters J, Torre T, Fearn P, Leibel S, Kattan MW. Potency after permanenet prostate brachytherapy for localized prostate cancer. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2001;50 doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urry D. Protein elasticity based on conformations of sequential polypeptides: The biological elastic fiber. J Protein Chem. 1984;3:403–436. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urry DW. Physical Chemistry of Biological Free Energy Transduction As Demonstrated by Elastic Protein-Based Polymers. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 1997;101:11007–11028. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu W, MacKay JA, Dreher MR, Chen M, McDaniel JR, Simnick AJ, Callahan DJ, Zalutsky M, Chilkoti A. Injectable intratumoral depot of thermally responsive polypeptide-radionuclide conjugates delays tumor progression in a mouse model. Journal of Controlled Release. 2010;144:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu W, McDaniel J, Li X, Asai D, Quiroz FG, Schaal J, Park JS, Zalutsky M, Chilkoti A. Brachytherapy using injectable seeds that are self-assembled from genetically encoded polypeptides in situ. Cancer research. 2012;72:5956–5965. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colomb J, HO, Trecker DJ. Radiation-Convertible Polymers from Norbornenyl Derivatives. Crosslinking with Ionizing Radiation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 1970;14 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cataldo F, Ursini O, Lilla E, Angelini G. Radiation-induced crosslinking of collagen gelatin into a stable hydrogel. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. 2008;275:125–131. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen M, Zhu J, Qi G, He C, Wang H. Anisotropic hydrogels fabricated with directional freezing and radiation-induced polymerization and crosslinking method. Materials Letters. 2012;89:104–107. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratner BD, Weathersby PK, Hoffman AS. Radiation-grafted hydrogels for biomaterial applications as studied by the ESCA technique. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 1978;22:643–664. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee J, MacOsko CW, Urry DW. Phase transition and elasticity of protein-based hydrogels. J Biomater Sci Polymer Edn. 2001;12:229–242. doi: 10.1163/156856201750180942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, MacOsko CW, Urry DW. Mechanical properties of cross-linked syntheti elastomeric polypentapeptides. Macromolecules. 2001;34:5968–5974. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDaniel JR, Radford DC, Chilkoti A. A Unified Model for De Novo Design of Elastin-like Polypeptides with Tunable Inverse Transition Temperatures. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:2866–2872. doi: 10.1021/bm4007166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood WG, Wachter C, Scriba PC. Experiences using chloramine-T and 1, 3, 4, 6-tetrachloro-3 alpha, 6 alpha-diphenylglycoluril (Iodogen) for radioiodination of materials for radioimmunoassay. Journal of clinical chemistry and clinical biochemistry Zeitschrift fur klinische Chemie und klinische Biochemie. 1981;19:1051–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkins DE, Shang-Fan Y, Hornig YS, Purchio T, Contag PR. In vivo monitoring of tumor relapse and metastasis using bioluminescent PC-3M-luc-C6 cells in murine models of human prostate cancer. Clinical & Experimental Metastasis. 2003;20:745–756. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000006817.25962.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan MH, Nowak NJ, Loor R, Ochi H, Sandberg AA, Lopez C, Pickren JW, Berjian R, Douglass HO, Jr, Chu TM. Characterization of a new primary human pancreatic tumor line. Cancer investigation. 1986;4:15–23. doi: 10.3109/07357908609039823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaighn ME, Narayan KS, Ohnuki Y, Lechner JF, Jones LW. Establishment and characterization of a human prostatic carcinoma cell line (PC-3) Investigative urology. 1979;17:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiu W, Su G. Development of Orthotopic Pancreatic Tumor Mouse Models. In: Su GH, editor. Pancreatic Cancer. Humana Press; 2013. pp. 215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cima G. AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animal: 2013 Edition. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2013;242:715–716. [Google Scholar]

- 35.NIoM Health. Methods and Welfare Considerations in Behavioral Research with Animal. In: Morrison A, Evans H, Ator N, Nakamura R, editors. Report of a National Institutes of Health Workshop. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDaniel J, Weitzhandler I, Prevost S, Vargo KB, Appavou MS, Hammer DA, Gradzielski M, Chilkoti A. Noncanonical self-assembly of highly asymmetric genetically encoded polypeptide amphiphiles into cylindrical micelles. Nano Letters. 2014;14:6590–6598. doi: 10.1021/nl503221p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciezki JP, Klein EA. Brachytherapy or surgery? A composite view. Oncology (Williston Park, NY) 2009;23:960–964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katakura J. Nuclear Data Sheets for A = 125. Nuclear Data Sheets. 2011;112:495–705. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khazov Y, Mitropolsky I, Rodionov A. Nuclear Data Sheets for A = 131. Nuclear Data Sheets. 2006;107:2715–2930. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Azhdarinia A, Yang DJ, Yu DF, Mendez R, Oh C, OKohanim S, Bryant J, Kim EE. Regional radiochemotherapy using in situ hydrogel. Pharm Res. 2005;22:776–783. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-2594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hruby M, Pouckova P, Zadinova M, Kucka J, Lebeda O. Thermoresponsive polymeric radionuclide delivery system -- an injectable brachytherapy. Eur J PHarm Sci. 2011;42:484–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hruby M, Kucka J, Lebeda O, Mackova H, Babic M, Konak C, Studenovsky M, Sikora A, Kozempel J, Ulbrich K. New bioerodable thermoresponsive polymers for possible radiotherapeutic applications. Journal of Controlled Release. 2007;119:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu YP, Yu Q, Guo JM, Jiang HT, Di XY, Zhu Y. Effectiveness and security of CT-guided percutaneous implantation of (125)I seeds in pancreatic carcinoma. The British journal of radiology. 2014;87:20130642. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun S, Qingjie L, Qiyong G, Mengchun W, Bo Q, Hong X. EUS-guided interstitial brachytherapy of the pancreas: a feasibility study. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2005;62:775–779. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du YQ, Li ZS, Jin ZD. Endoscope-assisted brachytherapy for pancreatic cancer: From tumor killing to pain relief and drainage. Journal of interventional gastroenterology. 2011;1:23–27. doi: 10.4161/jig.1.1.14596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.