Abstract

Background

Preemptive antiviral therapy relies on viral load measurements and is the mainstay of cytomegalovirus (CMV) prevention in hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients. However, optimal CMV levels for the initiation of preemptive therapy have not been defined.

Objectives

To evaluate the relationship between plasma CMV DNA levels at initiation of preemptive therapy with time to resolution of viremia and duration of treatment.

Study Design

Retrospective analysis of HCT recipients undergoing serial CMV PCR testing between June 2011 and June 2014 was performed.

Results

221 HCT recipients underwent preemptive therapy for 305 episodes of CMV viremia. Median time to resolution was shorter when treatment was initiated at lower CMV levels (15 days at 135-440 international units (IU)/mL, 18 days at 441-1000 IU/mL, and 21 days at >1000 IU/mL, P <.001). Prolonged viremia lasting >30 days occurred less frequently when treatment was initiated at 135-440 IU/mL compared to 441-1000 IU/mL and >1000 IU/mL (1%, 15%, 24%, P<.001). Median treatment duration was also shorter in the lower viral load groups (28, 34, 37 days, P <.001).

Conclusion

Initiation of preemptive therapy at low CMV levels was associated with shorter episodes of viremia and courses of antiviral therapy. These data support the utility of initiating preemptive CMV therapy at viral loads as low as 135 IU/mL in HCT recipients.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction, WHO International Standard, Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, Pre-emptive Therapy, viral load

1. Background

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients(1-3).Preemptive therapy strategies involving virologic monitoring and early intervention with antiviral therapy have been widely employed and successful in reducing CMV disease(4, 5).Quantitative nucleic acid amplification techniques have largely replaced pp65 antigenemia for early CMV detection and off erimproved sensitivity without loss of specificity(6-8).Despite the widespread use of quantitative PCR, there is no consensus regarding the CMV level at which preemptive therapy should be initiated(9-11).Some studies have suggested a threshold of 500 copies/mL, others 1000 copies/mL, while others suggest different thresholds dependent on recipient risk(12-15).This lack of consensus translates into significant heterogeneity in clinical practice.

Attempts to establish broadly applicable quantitative values to guide preemptive therapy have been hampered by significant inter-assay quantification variability. To improve result generalizability between centers using different assays, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the First WHO International Standard for Human Cytomegalovirus for Nucleic Acid Amplification Techniques, NIBSC code 09/162in 2010. Laboratories are now harmonizing quantitative CMV assays to the international standard and reporting results in international units (IU) rather than copies. While calibration to the WHO International Standard is an imperfect solution to inter-assay variability, the opportunity to provide comparable quantitative data across laboratories facilitates the development of guidelines with broadly applicable thresholds for diagnosing and managing CMV infection.

In the era of highly sensitive PCR assays and international calibration to the CMV WHO Standard, there is an unmet need to identify clinically relevant viral loads for the initiation of preemptive therapy in HCT recipients. In particular, the significance of low-level viremia and the impact of treatment initiation at various viral loads on clinically important outcomes require further investigation.

2. Objectives

To evaluate the relationship between CMV DNA levels in plasma at initiation of preemptive therapy, time to resolution of viremia, and duration of antiviral treatment in HCT recipients.

3. Study Design

3.1.Patient Population

We retrospectively reviewed results of quantitative CMV PCR testing in plasma performed at Stanford University Clinical Virology Laboratory. Between June 20, 2011 and June 30, 2014, 722 adult HCT recipients (age ≥18years) had 9610 tests performed. Of these, 256 HCT recipients, with 5578 CMV tests performed during monitoring for preemptive therapy, had at least one positive test result in the assay's linear range (≥135 IU/mL) and were evaluated in our study.

3.2. Quantitative CMV Testing

Testing was performed using the artus CMV Rotor-Gene PCR (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) as previously described(16).Viral load values were expressed in international units (IU/mL) based on the test's calibration to the primary CMV WHO standard obtained from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (Hertfordshire, UK).

3.3. Data Collection and Definitions

Demographic and clinical data for each HCT recipient with at least one CMV PCR result of ≥135 IU/mL were collected through medical record review. CMV disease was defined as a consistent clinical presentation with CMV detected by immunohistochemistry or PCR on biopsied tissue. An episode of CMV viremia was defined as the time period beginning with a quantitative CMV PCR result of ≥135 IU/mL and ending with resolution of viremia to an undetectable level or detectable but <135 IU/mL for two consecutive tests. The primary outcome of this study was the time to resolution of viremia following initiation of antiviral therapy. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of prolonged CMV viremia, defined as detectable and quantifiable CMV DNA for >30 days, and the duration of antiviral therapy.

For each episode, the CMV DNA level immediately prior to the initiation of antiviral therapy and the duration of treatment were identified by chart review. Viral load treatment threshold, choice and dose of antiviral, and duration of treatment were at the discretion of the clinician. Intravenous ganciclovir 5mg/kg every 12 hours or oral valganciclovir 900mg twice daily were the most common agents used for preemptive therapy. These agents were dosed for renal function and continued until the resolution of viremia, followed by 1-3 weeks of maintenance therapy, per protocol. CMV genotypic drug resistance testing (Focus Diagnostics, Cypress, CA), as ordered by the clinician during the study period, was evaluated as available.

3.4. Data Analysis

To assess for associations between the primary outcome and CMV DNA level at treatment initiation, treatment episodes were stratified into groups by viral load. A viral load of 1000 IU/mL at treatment initiation was selected based on prior literature supporting a similar threshold (1000 copies/mL) for CMV preemptive therapy(13, 15).To identify a significant viral load division below 1000 IU/mL, we used principal component analysis and found 440 IU/mL as the middle point in the data that displayed the largest variance across groups for time to resolution of viremia(17).

Episodes were then separated into three groups by viral load at treatment initiation: 135-440 IU/mL, 441-1000 IU/mL, and >1000IU/mL. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed using resolution of viremia as the primary event, and significance was determined with the log-rank test. Patients were right-censored if there was a lack of documented resolution of viremia or completion of treatment within the study period. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the relationship between the time to resolution of viremia and viral load at treatment initiation, while adjusting for relevant baseline covariates. The multivariate model incorporated covariates found to have a P value <.30 in the univariate analysis. The hazard ratio and median time to resolution including 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for each predictor. Where hazard ratios are shown, the category denoted by (1.00) was the reference group. Adjusted hazard ratios (AHR) >1.00 indicate a shorter time to resolution of viremia, whereas AHR values <1.00 indicates a longer time to resolution of viremia.

Continuous variables were compared between groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test and categorical variables were compared between groups using the Fisher's exact test. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 13.0 (College Station, Texas). A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

During the study period, 377 episodes of viremia developed among 256 HCT recipients. In 49 episodes, CMV viremia spontaneously resolved without treatment. 328 episodes among 221 HCT recipients were treated in response to aCMV PCR result of ≥135 IU/mL. 23 episodes were censored due to a lack of documented resolution of viremia or completion of treatment within the study period, resulting in a total of 305 treated episodes of viremia for primary and secondary outcome analysis. Treatment was initiated in 89 episodes at a viral load of 135-440 IU/mL [median 278 IU/mL, interquartile range (IQR) 202-343 IU/mL], 104at 441-1000 IU/mL (median 618 IU/mL, IQR 481-773), and 112 at >1000 IU/mL (median 2111 IU/mL, IQR1340-3590 IU/mL). The median duration between CMV tests during episodes was 7 days and was not significantly different between groups (P = .54). Patient character istics stratified by CMV DNA level at treatment initiation were comparable (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Viremic HCT Recipients Stratified by CMV DNA Levels at Initiation of Antiviral Therapy.

| Characteristic |

135-440 IU/mL (n=89) |

441-1000 IU/mL (n=104) |

>1000 IU/mL (n=1 12) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, ya | 55 (40-63) | 57 (43-63) | 57 (45-64) | .69 |

| Day from transplanta | 49 (29-129) | 47 (27-101) | 46 (28-92) | .44 |

| Indication | .53 | |||

| Acute leukemia | 41 (46) | 41 (39) | 46 (41) | |

| Chronic leukemia | 10 (11) | 12 (12) | 7 (6) | |

| Lymphoma | 25 (28) | 32 (31) | 32 (29) | |

| Otherb | 13 (15) | 19 (18) | 27 (24) | |

| Conditioning regimen | .76 | |||

| Myeloablative | 35 (39) | 37 (36) | 37 (33) | |

| Nonmyeloablative | 39 (44) | 49 (48) | 50 (45) | |

| Reduced intensity | 15 (17) | 17 (16) | 25 (22) | |

| Match | .58 | |||

| MRD | 33 (37) | 35 (34) | 38 (34) | |

| MURD | 28 (31) | 39 (38) | 41 (36) | |

| MMURD | 23 (26) | 27 (26) | 31 (28) | |

| Haploidentical | 4 (5) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Autologous | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| Stem cell source | .24 | |||

| PBC | 85 (96) | 89 (86) | 100 (89) | |

| BM | 4 (4) | 11 (11) | 9 (8) | |

| Umbilical | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | |

| CMV serostatus | .27 | |||

| D+/R+ | 55 (62) | 66 (65) | 61 (55) | |

| D+/R- | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | 6 (5) | |

| D-/R+ | 33 (37) | 32 (31) | 43 (38) | |

| Autologous (R+) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | |

| T-cell depletion | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | .11 |

| ATG | 46 (51) | 57 (55) | 65 (61) | .43 |

| Steroids | 58 (65) | 56 (54) | 67 (60) | .28 |

| GVHD | 29 (33) | 38 (37) | 41 (36) | .83 |

Abbreviations: HCT, hematopoietic cell transplant; CMV, cytomegalovirus; MRD; matched related donor; MURD, matched unrelated donor; MMURD, mismatched unrelated donor; PBC, peripheral blood cell; BM, bone marrow; ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; D+, donor serology positive; D-, donor serology negative; R+, recipient serology positive; R+, recipient serology negative; GVHD, graft versus host disease

Median (interquartile range), other table entries represent n (%).

Included myelodysplastic syndrome, myelofibrosis, aplastic anemia, multiple myeloma

4.1. Time to Resolution of Viremia

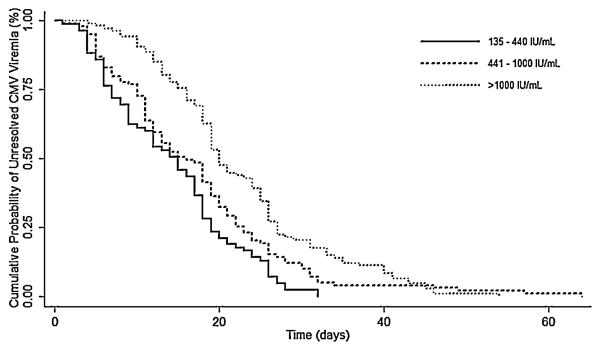

Median time to resolution of viremia was significantly shorter when treatment was initiated at lower viral loads: 15 days for 135-440 IU/mL, 18 days for 441-1000 IU/mL, 21 days at >1000 IU/mL (P <.001; Table 2).Kaplan-Meier analysis also demonstrated a difference in time to resolution of viremia for each treatment group (P<.001; Figure 1).In a multivariate analysis, the association between viral load at treatment initiation and duration of viremia remained significant (Table 3). With the >1000 IU/mL group as reference, the AHR for shortened duration of viremia was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.02-1.79, P =.03) for those treated at 441-1000 IU/mL and 2.10 (95% CI, 1.55-2.85, P<.001) at 135-440 IU/mL. A shorter time to resolution of viremia was also associated with a matched donor and non-lymphoma indication for HCT.

Table 2. Outcomes of CMV Viremia Episodes in HCT Recipients Stratified by CMV DNA Levels at Initiation of Antiviral Therapy.

| Characteristic |

135-440 IU/mL (n=89) |

441-1000 IU/mL (n=104) |

>1000 IU/mL (n=112) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median days to viremia resolution (95% CI) | 15 (10-17) | 18 (13-19) | 21 (20-25) | <.001a |

| Prolonged viremia >30 days (%) | 1 (1) | 16 (15) | 27 (24) | <.001 |

| Median days on antiviral treatment (95% CI) | 28 (26-30) | 34 (31-37) | 37 (34-40) | <.001a |

| Median days of treatment after viremia resolution (IQR) | 14 (9-21) | 16 (10-24) | 14 (9-22) | .18 |

| CMV disease | 5 (6) | 9 (8) | 8 (7) | .73 |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplant; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range

P value by log-rank test

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of time to resolution of CMV viremia by CMV DNA level at initiation of antiviral treatment. With the >1000 IU/mL group as reference, the adjusted hazard ratio was 1.35 (95% confidence interval, 1.02-1.79, P = .03) for the 441-1000 IU/mL group and 2.10 (95% confidence interval, 1.55-2.85, P<.001) for the 135-440 IU/mL group. The graph does not show 9 cases in the 441–1000 IU/mL and >1000 IU/mL groups where viremia resolved beyond 75 days.

Table 3. Multivariate Analysis of Predictors for Time to Resolution of CMV Viremia Among HCT Recipients.

| Multivariate Analysisa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | AHR | 95% CI | P Value |

| CMV viral load | |||

| 135-440 IU/mL | 2.10 | (1.55-2.85) | <.001 |

| 441-1000 IU/mL | 1.35 | (1.02-1.79) | .03 |

| >1000 IU/mL | (1.00)b | ||

| Indication | |||

| Acute leukemia | 1.53 | (1.09-2.14) | .01 |

| Chronic leukemia | 1.77 | (1.12-2.80) | .01 |

| Other | 1.51 | (1.04-2.19) | .03 |

| Lymphoma | (1.00) | ||

| Conditioning regimen | |||

| Myeloablative | 1.05 | (.64-1.72) | .85 |

| Nonmyeloablative | 1.08 | (.75-1.56) | .68 |

| Reduced intensity | (1.00) | ||

| Match | |||

| MRD | 1.99 | (1.38-2.85) | <.001 |

| MURD | 1.48 | (1.07-2.04) | .02 |

| Haploidentical | 1.61 | (.59-4.39) | .36 |

| Autologous | 3.20 | (.89-11.45) | .07 |

| MMURD | (1.00) | ||

| Stem cell source | |||

| PBC | 1.67 | (.58-4.82) | .35 |

| BM | 1.30 | (.40-4.15) | .66 |

| Umbilical | (1.00) | ||

| ATG | |||

| No | 1.02 | (.63-1.66) | .93 |

| Yes | (1.00) | ||

| CMV serostatus | |||

| D+/R+ | 1.15 | (.89-1.48) | .27 |

| D+/R- | 1.19 | (.58-2.45) | .64 |

| D-/R+ | (1.00) | ||

| CMV disease | |||

| No | 1.17 | (.74-1.85) | .50 |

| Yes | (1.00) | ||

| Steroids | |||

| No | 1.30 | (.95-1.76) | .10 |

| Yes | (1.00) | ||

| GVHD | |||

| Yes | 1.07 | (.80-1.44) | .64 |

| No | (1.00) |

Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplant; AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; MRD; matched related donor; MURD, matched unrelated donor; MMURD, mismatched unrelated donor; PBC, peripheral blood cell; BM, bone marrow; ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; D+, donor serology positive; D-, donor serology negative; R+, recipient serology positive; R+, recipient serology negative; GVHD, graft versus host disease

Final model included covariates with a P value <.30 by univariate analysis with log-rank statistic

Hazard ratio estimates within parentheses (1.00) indicate reference categories

4.2. Spontaneously Resolving Episodes

Median peak viral load for the 49 episodes that spontaneously resolved without antiviral therapy was 206 IU/mL, with a maximum peak viral load of 601 IU/mL. These episodes were matched to a comparison group of 84 episodes with an initial median viral load of 208 IU/mL (IQR: 167-288 IU/mL) that was followed by an increase in viral load to >440 IU/mL within 7 days and initiation of preemptive therapy. These 84 episodes accounted for 40% of the 216 episodes where treatment was initiated at a viral load >440 IU/mL and had a median viral load of 1,110 IU/mL (IQR: 503-10,500 IU/mL) at treatment initiation. These two groups were similar when compared using the variables shown in Table 1 except that episodes with spontaneous resolution were significantly less likely to have new or worsening GVHD diagnosed within the prior month (4% vs 36%, P<.001). Furthermore, episodes that spontaneously resolved did not have CMV disease diagnosed during the episode of viremia (0% vs 10%, P = .03).

4.3. Prolonged Viremia

Consistent with the time to resolution of viremia, prolonged episodes of viremia lasting >30 days occurred less frequently in the lower viral load treatment groups (1% vs 15% vs 24%, P<.001; Table 2). The number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one episode of prolonged viremia when treatment was initiated at 135-440 IU/mL was 7.1 compared to 441-1000 IU/mL and 4.3 compared to>1000 IU/mL. Genotypic drug resistance testing was performed during16/44(36%) of these prolonged episodes, resulting in the identification three UL97 mutations: one (C592G) in the 441-1000 IU/mL group and two (M460V, L595S) in the >1000 IU/mL group.

4.4. Treatment Duration

Median treatment duration for episodes in which therapy was initiated at 135-440 IU/mL, 441-1000IU/mL, and>1000IU/mL were 28, 34, and 37 days, respectively (P<.001; Table 2).Treatment was continued for a median duration of 14-16days after resolution of viremia and was not significant across groups (P = .18; Table 2).Preemptive therapy was initiated with valganciclovir or ganciclovir in 88%, foscarnet in 4%, and alternating ganciclovir and foscarnet in 8% of episodes. Initial treatment did not differ across groups (P =.78).

5. Discussion

Despite the widespread use of CMV monitoring to guide preemptive antiviral therapy, clinical practice guidelines have yet to provide recommendations on when to initiate preemptive therapy in HCT recipients. Prior attempts at defining broadly applicable viral load thresholds have been limited by significant inter-assay quantification variability. However, the implementation of the CMV WHO International Standard for assay calibration now facilitates comparisons of viral load measurements across laboratories and may allow for clinically meaningfully interpretation of these quantitative values.

This study emphasizes the clinical importance of CMV viral load at treatment initiation in HCT recipients undergoing preemptive therapy. We found that the initiation of preemptive therapy at lower CMV viral loads was associated with shorter episodes of viremia and decreased risk for prolonged viremia lasting >30 days. Prolonged viremia and high peak viral loads are associated with the development of antiviral resistance and CMV disease; thus, efforts towards minimizing duration of viremia may provide substantial clinical benefit(18-21).Additionally, preemptive therapy started at lower viral loads was associated with shorter treatment duration. Shorter exposure to antivirals, particularly ganciclovir and foscarnet, may minimize toxicity such as leukopenia and acute renal injury, and reduces the need for frequent drug level monitoring for dose adjustments(22).

A limited number of previous studies evaluated CMV DNA levels at the initiation of preemptive therapy, though none have been designed to identify differences in time to resolution of viremia or duration of treatment. In the study by Einsele, et al., which preceded the widespread use of quantitative CMV PCR in clinical laboratories, qualitative CMV PCR and viral culture were compared in a preemptive therapy strategy. The more sensitive PCR assay was found to result in earlier CMV detection and shortened duration of treatment(22).Two additional studies investigated the association of viral load at treatment initiation, reported in locally defined copies/mL, with a delayed virologic response. However, rather than time to resolution of viremia, delayed virologic response was defined as an increase in CMV DNA levels early after treatment initiation. While one study reported an association between higher viral loads at the initiation of therapy and a delayed virologic response, the other did not(14, 23).

Though the findings presented here demonstrate a benefit to starting preemptive therapy at CMV viral loads as low as 135 IU/mL, early antiviral therapy may lead to unnecessary treatment for episodes of CMV viremia that may have resolved spontaneously. In our study, the diagnosis of GVHD within the preceding month was associated with rising CMV levels and eventual treatment, though this criterion was insensitive for identifying patients who may benefit from early antiviral therapy. As might be expected, CMV disease was not diagnosed among episodes of CMV viremia that spontaneously resolved. Importantly, improved methods areneeded for differentiating episodes of low level viremia that are likely to spontaneously resolve from those that will not. Other studies have suggested that measuring the rate of increase in CMV viral load allows the differentiation of these episodes(14, 24).However, this strategy would result in delayed initiation of therapy for patients whose viral loads continued to rise and, based on our findings, lead to longer episodes of viremia, increase the risk for prolonged viremia, and require longer courses of antiviral therapy.

In multivariate analyses, we also found that having a non-lymphoma indication or receiving an HLA-matched transplant was associated with a shorter duration of viremia. Differences in underlying immunologic function may explain these findings, though further work will be required to characterize the mechanisms that contribute to CMV resolution in these patients.

Limitations in our study involve practice patterns that were dictated by the provider, including selection of antiviral agent, dose, and duration. No drug level monitoring was performed to confirm standardized treatment and CMV genotypic drug resistance testing was performed in a minority of patients, which precluded a detailed analysis of the effect of resistance on outcomes. Additionally, provider initiation of preemptive therapy at low viral loads limited our ability to fully evaluate the natural history of low-level CMV viremia and better characterize episodes that may spontaneously resolve.

This study, to date, is the largest evaluation of CMV DNA levels in HCT recipients undergoing preemptive monitoring with CMV testing harmonized to the WHO International Standard. We suggest that preemptive therapy may be started at CMV DNA levels as low as 135 IU/mL to reduce the time to resolution of viremia and the duration of therapy. Though findings in this study offer insight into the clinical benefits of initiating preemptive CMV therapy at low viral loads, further studies are needed to better discriminate patients with low level viremia that are likely to spontaneously resolve from those that require an immediate therapeutic intervention.

Highlights.

Preemptive therapy is the basis of CMV prevention in HCT recipients.

Retrospectively evaluated CMV levels at the initiation of preemptive therapy.

The rapy initiation at low viral loads was associated with shorter time to resolution of viremia.

Prolonged episodes of viremia lasting >30 days occurred less frequently.

Therapy initiation at low viral loads was associated with shorter treatment duration.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Stan Deresinski, Dora Ho, Robert Lowsky, and Aruna Subramanian for their thoughtful comments on this manuscript. We also thank the staff of the Stanford Clinical Virology Laboratory for their continued exceptional work and dedication.

Funding: Salary support was provided by NIH training grant 5T32AI007502-19 (SKT, JJW) and a generous gift from Beta Sigma Phi (SKT), an international women's service organization. Further salary support was provided by NIH award K08 AI110528-01 (JJW).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the Journal of Clinical Virology.

Ethical Approval: This study was reviewed and approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board.

References

- 1.Boeckh M, Leisenring W, Riddell SR, Bowden RA, Huang ML, Myerson D, et al. Late cytomegalovirus disease and mortality in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants: importance of viral load and T-cell immunity. Blood. 2003;101(2):407–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Humar A, Wood S, Lipton J, Messner H, Meharchand J, McGeer A, MacDonald K, Mazzulli T. Effect of cytomegalovirus infection on 1-year mortality rates among recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplants. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(3):606–10. doi: 10.1086/514569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaia JA. Prevention of cytomegalovirus disease in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(8):999–1004. doi: 10.1086/342883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winston DJ, Ho WG, Bartoni K, Du Mond C, Ebeling DF, Buhles WC, et al. Ganciclovir prophylaxis of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in allogeneic bone marrow transplant recipients. Results of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):179–84. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodrich JM, Bowden RA, Fisher L, Keller C, Schoch G, Meyers JD. Ganciclovir prophylaxis to prevent cytomegalovirus disease after allogeneic marrow transplant. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):173–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-3-199302010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchetti S, Santangelo R, Manzara S, D'onghia S, Fadda G, Cattani P. Comparison of real-time PCR and pp65 antigen assays for monitoring the development of Cytomegalovirus disease in recipients of solid organ and bone marrow transplant. The new microbiologica. 2011;34(2):157–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cariani E, Pollara CP, Valloncini B, Perandin F, Bonfanti C, Manca N. Relationship between pp65 antigenemia levels and real-time quantitative DNA PCR for Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) management in immunocompromised patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-7-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardenoso L, Pinsky BA, Lautenschlager I, Aslam S, Cobb B, Vilchez RA, et al. CMV antigenemia and quantitative viral load assessments in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. J Clin Virol. 2013;56(2):108–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emery V, Zuckerman M, Jackson G, Aitken C, Osman H, Pagliuca A, et al. Management of cytomegalovirus infection in haemopoietic stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2013;162(1):25–39. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ljungman P, Hakki M, Boeckh M. Cytomegalovirus in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipient. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2011;25(1):151–69. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boeckh M, Ljungman P. How we treat cytomegalovirus in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Blood. 2009;113(23):5711–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-143560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peres RM, Costa CR, Andrade PD, Bonon SH, Albuquerque DM, de Oliveira C, et al. Surveillance of active human cytomegalovirus infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HLA sibling identical donor): search for optimal cutoff value by real-time PCR. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halfon P, Berger P, Khiri H, Martineau A, Penaranda G, Merlin M, et al. Algorithm based on CMV kinetics DNA viral load for preemptive therapy initiation after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Med Virol. 2011;83(3):490–5. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munoz-Cobo B, Solano C, Costa E, Bravo D, Clari MA, Benet I, et al. Dynamics of cytomegalovirus (CMV) plasma DNAemia in initial and recurrent episodes of active CMV infection in the allogeneic stem cell transplantation setting: implications for designing preemptive antiviral therapy strategies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(11):1602–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green ML, Leisenring W, Stachel D, Pergam SA, Sandmaier BM, Wald A, et al. Efficacy of a viral load-based, risk-adapted, preemptive treatment strategy for prevention of cytomegalovirus disease after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(11):1687–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waggoner J, Ho DY, Libiran P, Pinsky BA. Clinical significance of low cytomegalovirus DNA levels in human plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(7):2378–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06800-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ringner M. What is principal component analysis? Nature biotechnology. 2008;26(3):303–4. doi: 10.1038/nbt0308-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lurain NS, Chou S. Antiviral drug resistance of human cytomegalovirus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(4):689–712. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00009-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lengerke C, Ljubicic T, Meisner C, Loeffler J, Sinzger C, Einsele H, et al. Evaluation of the COBAS Amplicor HCMV Monitor for early detection and monitoring of human cytomegalovirus infection after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone marrow transplantation. 2006;38(1):53–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Einsele H, Hebart H, Kauffmann-Schneider C, Sinzger C, Jahn G, Bader P, et al. Risk factors for treatment failures in patients receiving PCR-based preemptive therapy for CMV infection. Bone marrow transplantation. 2000;25(7):757–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeon S, Lee WK, Lee Y, Lee DG, Lee JW. Risk factors for cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with cytomegalovirus viremia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(9):1892–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Einsele H, Ehninger G, Hebart H, Wittkowski KM, Schuler U, Jahn G, et al. Polymerase chain reaction monitoring reduces the incidence of cytomegalovirus disease and the duration and side effects of antiviral therapy after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1995;86(7):2815–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buyck HC, Griffiths PD, Emery VC. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) replication kinetics in stem cell transplant recipients following anti-HCMV therapy. J Clin Virol. 2010;49(1):32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gimenez E, Munoz-Cobo B, Solano C, Amat P, Navarro D. Early kinetics of plasma cytomegalovirus DNA load in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients in the era of highly sensitive real-time PCR assays: does it have any clinical value? J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(2):654–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02571-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]