Dear Editor:

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome, is an autosomal dominant vascular disorder manifested by variable-sized arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) of the skin, central nervous system, and respiratory, gastrointestinal, and urogenital tracts1,2.

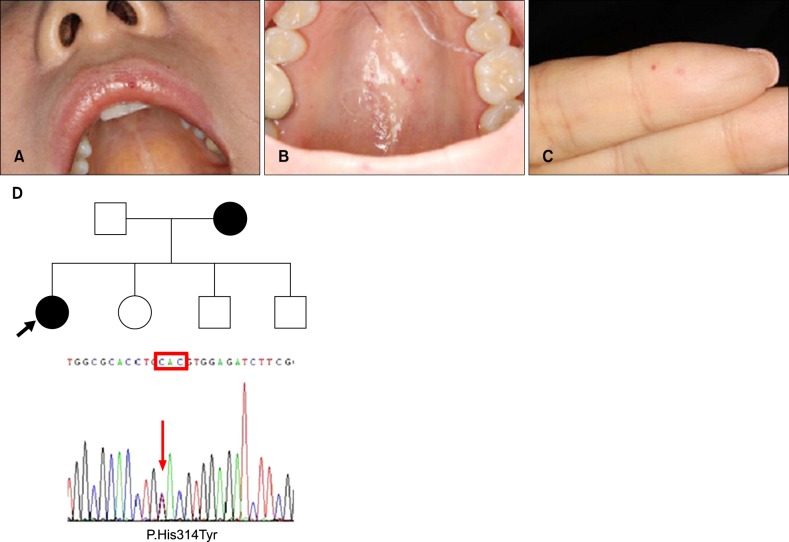

A 43-year-old woman visited our dermatology clinic with a 3-year history of increasing numbers of purpuric, punctate, and tiny macules of the lip, oral cavity, and fingers (Fig. 1A~C). The patient had no history of recurrent epistaxis; however, her mother had recurrent epistaxis and brain AVMs. No other abnormalities were detected in laboratory workups, particularly to detect visceral AVMs, including computed tomography scans of the chest and abdomen, brain magnetic resonance imaging, and gastrointestinal endoscopy. Under clinical suspicion, we performed a mutation analysis for HHT in the patient and her mother. The mutation c.940C>T (p.His314Tyr) in activin receptor-like kinase-1 (ACVRL1) was confirmed in both the patient and her mother, confirming the diagnosis of HHT (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, this genetic alteration, previously reported in a Western pedigree3, is a novel point mutation in a Korean family. The cutaneous lesions were well improved by pulsed dye laser (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. (A~C) Typical cutaneous telangiectasias at characteristic sites: lip, oral cavity, and fingers. (D) Presence of the mutation c.940C>T (p.His314Tyr) in activin receptor-like kinase-1.

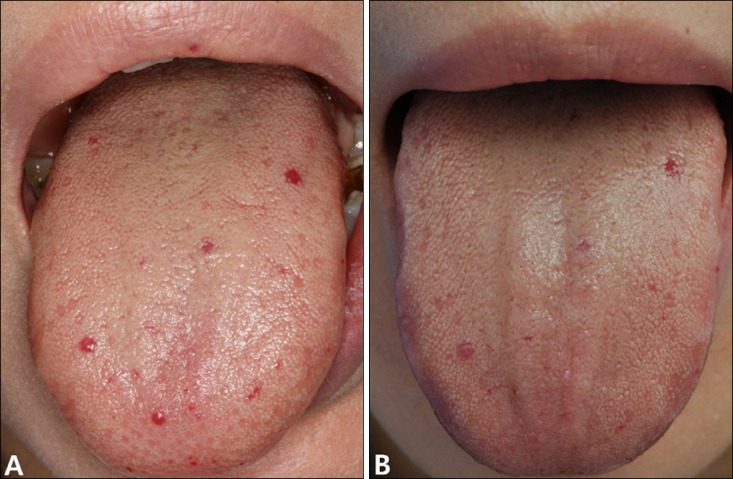

Fig. 2. Skin lesions on the tongue showed excellent response after a single treatment using pulsed dye laser (Vbeam Perfecta; Candela Laser Corporation, Wayland, MA, USA): (A) before treatment and (B) after treatment.

Clinically, HHT is diagnosed by the Curaçao criteria, which include spontaneous and recurrent epistaxis, mucocutaneous telangiectasias, visceral AVMs, and family history of HHT in a first-degree relative1,3. HHT is definitively diagnosed when three of the criteria are satisfied, whereas a suspected diagnosis is given when two of the criteria are met. In molecular diagnosis, mutations are found in approximately 85% of HHT families; most of these cases involve mutations in the endoglin (HHT1) or ACVRL1 (HHT2) genes4. Mutations of the endoglin gene on chromosome 9, which cause HHT1, were not detected in this family. The prevalence of specific vascular abnormalities varies according to genotype; patients with HHT1 have a higher prevalence of pulmonary and cerebral AVMs, while hepatic AVMs occur more commonly in HHT2 patients4. In our case, although the patient and her mother did not fulfill the criteria for a definitive diagnosis, HHT was strongly suspected because of the patient's typical mucocutaneous lesions. Therefore, targeted genetic testing for the endoglin and ACVRL1 genes should be performed to establish an early diagnosis if there are characteristic cutaneous features and/or a family history of HHT.

The cutaneous stigmata, which are characterized by an accumulation of small-caliber and superficial vessels, can cause cosmetic concerns and a risk for bleeding1,2,5. In our case, treatment with pulsed dye laser resulted in dramatic improvement of the skin lesions, similar to results reported by Halachmi et al.2. Multiple treatments and follow-up visits can be necessary because of the lower response of HHT than non-HHT telangiectasia and the possible accumulation of new vascular lesions2.

In conclusion, to initially rule out an HHT diagnosis, genetic study is an available option. Because of the superficial nature of vascular lesions, shorter wavelength vascular lasers such as the pulsed dye laser can be considered an effective and safe treatment option for HHT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by a grant (HI12C-0022-030014) from the Korea Healthcare technology R&D Project, Ministry for Health & Welfare Affairs.

References

- 1.Lee HE, Sagong C, Yeo KY, Ko JY, Kim JS, Yu HJ. A case of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:206–208. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halachmi S, Israeli H, Ben-Amitai D, Lapidoth M. Treatment of the skin manifestations of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia with pulsed dye laser. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29:321–324. doi: 10.1007/s10103-013-1346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesca G, Plauchu H, Coulet F, Lefebvre S, Plessis G, Odent S, et al. French Rendu-Osler Network. Molecular screening of ALK1/ACVRL1 and ENG genes in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in France. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:289–299. doi: 10.1002/humu.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shovlin CL. Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Blood Rev. 2010;24:203–219. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dave RU, Mahaffey PJ, Monk BE. Cutaneous lesions in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: successful treatment with the tunable dye laser. J Cutan Laser Ther. 2000;2:191–193. doi: 10.1080/146288300750163763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]