Abstract

The begomoviruses (family Geminiviridae) associated with cotton leaf curl disease (CLCuD) pose a major threat to cotton productivity in South–East Asia including Pakistan and India. These viruses have single-stranded, circular DNA genome, of ∼2800 nt in size, encapsidated in twinned icosa-hedera, transmitted by ubiquitous whitefly and are associated with satellite molecules referred to as alpha- and betasatellite. To circumvent the proliferation of these viruses numerous techniques, ranging from conventional breeding to molecular approaches have been applied. Such devised strategies worked perfectly well for a short time period and then viruses relapse due to various reasons including multiple infections, where related viruses synergistically interact with each other, virus proliferation and evolution. Another shortcoming is, until now, that all molecular biology approaches are devised to control only helper begomoviruses but not to control associated satellites. Despite the fact that satellites could add various functions to helper begomoviruses, they remain ignored. Such conditions necessitate a very comprehensive technique that can offer best controlling strategy not only against helper begomoviruses but also their associated DNA-satellites. In the current scenario clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR associated nuclease 9 (Cas9) has proved to be versatile technique that has very recently been deployed successfully to control different geminiviruses. The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been proved to be a comprehensive technique to control different geminiviruses, however, like previously used techniques, only a single virus is targeted and hitherto it has not been deployed to control begomovirus complexes associated with DNA-satellites. Here in this article, we proposed an inimitable, unique, and broad spectrum controlling method based on multiplexed CRISPR/Cas9 system where a cassette of sgRNA is designed to target not only the whole CLCuD-associated begomovirus complex but also the associated satellite molecules.

Keywords: begomoviruses, alphasatellite, betasatellites, cotton leaf curl disease, CRISPR/Cas9

Introduction

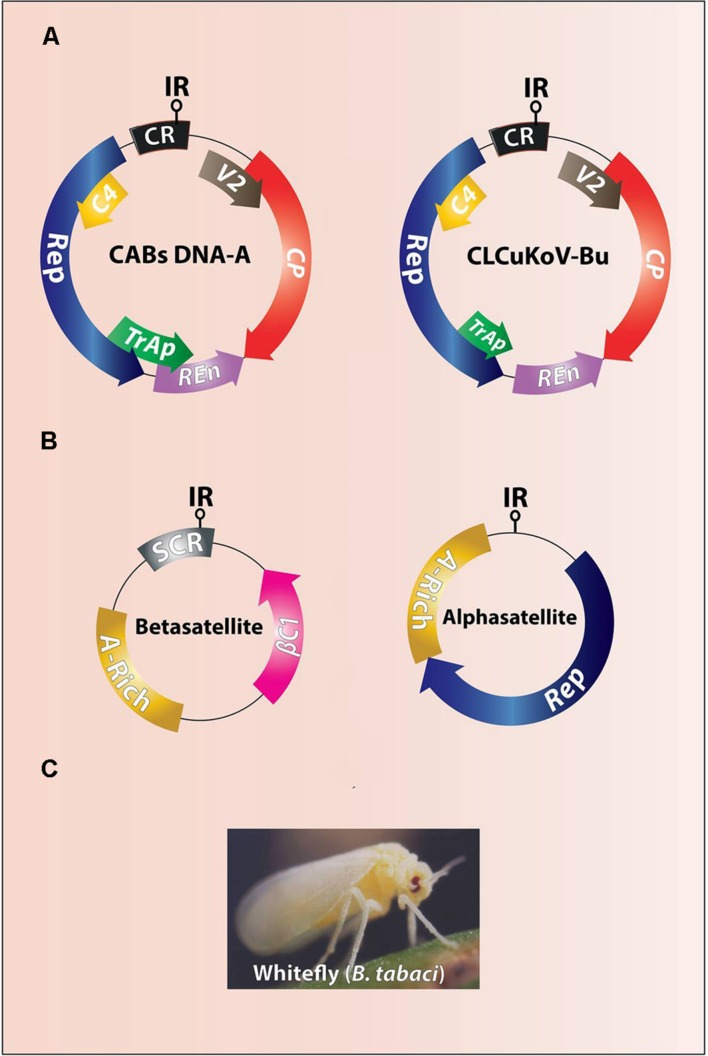

Cotton leaf curl disease (CLCuD) is a top ranked endemic disease to cotton in Pakistan, northwestern India and Africa, and causes a severe short fall in the economy thus, it is detrimental to the socio-economic values of the people (Mansoor et al., 2003; Varma and Malathi, 2003; Sattar et al., 2013). CLCuD on the Indian subcontinent is caused by a complex of begomoviruses in association with certain satellite molecules (alpha- and betasatellite). Viruses included in this complex are Cotton leaf curl Alabad Virus (CLCuAlV), Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus (CLCuBaV), Cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus (CLCuKoV), CLCuKoV-Bu (Burewala strain), Cotton leaf curl Multan virus (CLCuMuV), and Cotton leaf curl Rajasthan virus (CLCuRaV) (Zhou et al., 1998; Kirthi et al., 2004; Yousaf et al., 2013). All CLCuD-associated begomoviruses (CABs) induce typical symptoms of leaf curling (upward and downward), vein swelling, enation, and stunted growth (Figure 1). CABs belonging to genus begomovirus (Family Geminiviridae) are exclusively transmitted by ubiquitous whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) and have a circular single-stranded DNA genome of ∼2800 nt in size (Figure 2A) encapsidated in twinned quasi-icosahedera (Briddon and Markham, 2001; Böttcher et al., 2004). The genome of CABs encodes six genes in bi-directional manner separated by non-coding intergenic regions (IR), containing promoter elements and the origin of replication (Figure 2A). Two virion sense genes, the coat protein (CP) and V2 (pre-coat protein), are involved in insect transmission, encapsidation, in planta movement and suppression of host defense (Rojas et al., 2001). The remaining four complementary sense genes include the replication-associated protein [(Rep; sole protein involved in viral replication; (Hanley-Bowdoin et al., 2004)], the C2/TrAP protein [(transcriptional activator protein; involved in suppression of host defense, activation of late genes and overcomes virus induced hypersensitive cell death; Hussain et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2007; Mubin et al., 2010)], the replication enhancer protein C3/REn; (Settlage et al., 2005) and the C4 protein [(a pathogenicity/symptoms determinant and a suppressor of PTGS; Vanitharani et al., 2004; Saeed et al., 2008; Iqbal et al., 2012; Sunitha et al., 2013)]. Contrary to helper begomovirus, beta- and alphsatellites are half the size (∼1350 nt) of their helper begomoviruses, each encoding a single protein βC1 and Rep, respectively (Mansoor et al., 2001; Briddon et al., 2004) (Figure 2B). Of these two DNA-satellites, betasatellites are more diverse and their encoded single protein, βC1, adds more functions towards the viral pathogenesis than the alphasatellites. This protein is a suppressor of host defense, a pathogenicity/symptom determinant (Saeed et al., 2005; Qazi et al., 2007), may be involved in movement (Saeed et al., 2007), increases the helper begomovirus titer (Briddon et al., 2001), complements the missing functions of helper begomovirus genes (Iqbal et al., 2012), modulates the levels of developmental microRNAs (Amin et al., 2011), binds to DNA/RNA in sequence independent manner (Cui et al., 2005), interacts with various host-encoded factors, forms multimers, and also interacts with CP (Cheng et al., 2011), and suppresses jasmonic acid production in plants (Zhang et al., 2012).

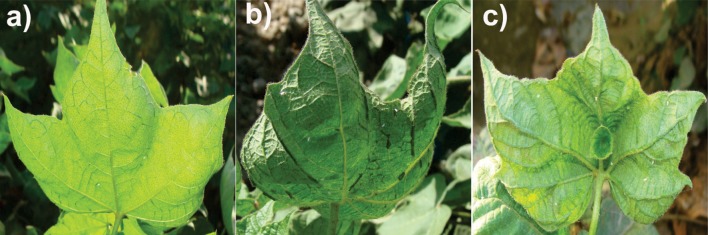

FIGURE 1.

Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) plants showing typical symptoms of CLCuD caused by CAB (s) alone (a), associated with alpha- and betasatellite (b,c), respectively. Presence of betasatellite incurred severe vein thickening and leaf enations on the underside of the leaves.

FIGURE 2.

Genome organization of CABs (A) and associated DNA-satellites (B). The difference between genomes of resistance breaking CLCuKoV-Bu and other CABs is of a truncated TrAP (A). The intergenic region (IR) contains stem loop structure and the origin of replication (ori). The CABs and associated DNA-satellites are vectored by ubiquitous whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) (C).

Although the exact history of CLCuD is difficult to map, CLCuD was, however, established in the sub-continent due to introgression of high yielding but highly susceptible varieties of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) in place of local resistant cotton species (G. arboreum) (Ali, 1997). Symptoms of this disease were discerned in 1967 near Multan, Pakistan (Hussain and Ali, 1975). Later in 1980, its first outbreak linked with dramatic decrease in cotton productivity gave scientists and policy makers cause for serious concern. In 1992–1997, it surged again and about 0.2 million hectares (mha) out of 2.5 mha were affected resulting in 29% reduction in cotton productivity and the country had to suffer a short fall in economy of about $US 5 billion (Briddon and Markham, 2001). Subsequently, CLCuD spread across the borders and reported from Sriganganagar, India in 1993 (Kumar et al., 2010). In the last decade of the previous century, continuous conventional breeding efforts and introduction of resistant/tolerant cotton varieties in Pakistan heaved the economy. However, in 2001–2004, the second outbreak was observed and the disease spread to southern parts of Pakistan, the Sindh province. Later, investigations showed that this outbreak was associated with a recombinant begomovirus, Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus associated with recombinant Cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite (CLCuMuB) (Briddon, 2003; Mahmood et al., 2003). Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus, now referred as CLCuKoV-Bu (Brown et al., 2015), has also been established widely in India (Rajagopalan et al., 2012; Zaffalon et al., 2012). Recently, different variants of CLCuKoV-Bu have been identified from Pakistan and India (Shuja et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2015), hence posing the possibility of another alarming situation that can lead to the third outbreak in sub-continent. Until now, despite all efforts (both conventional and molecular approaches) the almost the whole available germplasm is susceptible, except few lines which are claimed to be tolerant, against this menace (Rahman and Zafar, 2007).

The failure of controlling strategies against these begomoviruses has urged the scientists to explore better measures to control CLCuD. In the current scenario, CRISPR/Cas9, as an extremely versatile, multifaceted and emerging technology, has gained the attention of research communities across the globe. This system has recently been exploited successfully against Bean yellow dwarf virus (BeYDV) (Baltes et al., 2015), Beet severe curly top virus (BSCTV) (Ji et al., 2015), and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) (Ali et al., 2015), where reduced viral load up to 97% has been achieved linked to attenuated disease symptoms and apparently with no off-target affects. Keeping in mind the successful implementation of CRIPSR/Cas9, here in this study, a tentative methodology based on multiplex CRIPSR/Cas9 system is proposed, where universal sgRNAs are designed to target the most conserved regions of CABs and their associated DNA-satellite molecules that can potentially interfere with replication and movement of CABs and their cognate satellites, hence can resuscitate the cotton production by curbing CLCuD.

Why CRIPSR/Cas9 Against CLCUD?

In the past few decades, CABs have proliferated extensively. Their evolution and dispersion may likely be exacerbated by recombination, selection pressure imposed by introgression of resistant cultivars, change in virus complex and rise in temperature due to global warming. Despite concerted efforts made against CLCuD (see Techniques Employed to Control Cabs), nothing has been entirely successful in yielding resistance to this disease (Farooq et al., 2011; Sattar et al., 2013). The prevalent situation of unfruitful controlling strategies against CLCuD necessitates devising more strict controlling mechanisms that can curtail the CABs and their associated satellites. Under such circumstances, CRISPR/Cas9 system offers substantial advantage. The CRISPR/Cas9 system, apart from Zinc finger (ZFN) and Transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), has gained the attention of scientists across all major fields of science, especially plant biologists, as a promising programmable genome editing tool with higher level of specificity. Moreover, robustness, wide adaptability, and easy engineering of this system have proved its potential as a tool to control viruses – especially CABs. Very recently, this has also been successfully used to control plant viruses including different geminiviruses (Ali et al., 2015; Baltes et al., 2015; Ilardi and Tavazza, 2015; Ji et al., 2015). At the advent of CRISPR/Cas9 system, the major limitation observed was the degree to which off-target mutations take place. Until now, only few studies showed very negligible off-target activities. Improved versions of CRISPR/Cas9 DNA editing system and bioinformatics tools (Table 1) have increased the specificity to next level. New versions of sgRNAs can direct endonuclease Cas9 to induce precise cleavage at a target site (Jinek et al., 2012). In short, this system has validated the capability across a wide range of living organism to accomplish gene interference, where it has demonstrated its applicability and efficacy, thus rendering it as a final choice to curb viral diseases (Feng et al., 2013; Li et al., 2013), especially against CABs.

Table 1.

Available bioinformatics tools for selecting optimal CRISPR/Cas9 target sites and predicting off-targets.

| Purpose | Web address | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 design tool to find target sites within an input sequence. | http://www.genome-engineering.org | Hsu et al., 2013 |

| Designed sgRNA can be checked for off-targets and specificity against different genomes including Arabidopsis thaliana. | http://crispr.mit.edu/ | Ran et al., 2013 |

| Online tool for designing highly active sgRNAs. | http://www.broadinstitute.org/mai/public/analysis-tools/sgma-design | Doench et al., 2014 |

| Open sourced tool that is used locally, designed to identify potential off-target sites in any user specified genome. | http://eendb.zfgenetics.org/casot/ | Xiao et al., 2014 |

| Download link to access 38 plant genomes. | http://plants.ensembl.org/info/website/ftp/index.html | |

| Web-based tool to design sgRNA sequences for genome library projects or individual sequences. Target site homology is also evaluated to predict off targets. Five plant genomes are available. | http://www.e-crisp.org/E-CRISP/designcrispr.html | Heigwer et al., 2014 |

| Eight representative plant genomes are available to predict sgRNAs with low chance of off-target sites. | www.genome.arizona.edu/crispr | Xie et al., 2014 |

| Online tool for accurate target sequence selection and prediction of off-target binding of sgRNAs. Includes the design of target specific primers for PCR genotyping. The only plant genome available is A. thaliana. | https://chopchop.rc.fas.harvard.edu/ | Montague et al., 2014 |

| Cas-OFFinder. | http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/ | Kleinstiver et al., 2016 |

| Addgene service of non-profit plasmid distribution. | http://www.addgene.org/crispr/church/ | Mali et al., 2013 Kleinstiver et al., 2016 |

| http://www.addgene.org/crispr-cas | ||

| Software for the analysis of GUIDE-seq. | http://www.jounglab.org/guideseq | Kleinstiver et al., 2016 |

| Database that identifies Cas proteins and CRISPRs; includes many features complementary to CRISPR. | http://crispi.genouest.org/ | Bhaya et al., 2011 |

| CRISPR database; includes several tools to identify and analyze CRISPRs. Maintained by Universite Paris Sud. | http://crispr.upsud.fr/ | Bhaya et al., 2011 |

| To obtain Cas genes sequences. | http://mbgd.genome.ad.jp | Bolotin et al., 2005 |

| http://ergo.integratedgenomics.com/ERGO | ||

| Cas9 online designer. | http://cas9.wicp.net/ | Wang et al., 2016 |

Techniques Employed to Control CABs

A diverse group of techniques ranging from conventional breeding to advance molecular approaches have been implicated to control CLCuD, however, over time, resistance or tolerance was broken down by the virus (Aragão and Faria, 2009). Such techniques include accustom breeding approaches (Siddig, 1970; Ali, 1997; Rahman, 1997; Iqbal et al., 2001; Ahmad et al., 2010, 2011; Akhtar et al., 2010), pathogen derived resistance (PDR) including protein and non-protein mediated resistance (Amudha et al., 2010, 2011; Yousaf et al., 2013) (Asad et al., 2003; Sanjaya et al., 2005; Mubin et al., 2011; Ali et al., 2013; Tahir, 2014), DNA interference (Liu et al., 1998; Tahir, 2014), and non-PDR including expression of cry1Ac and GroEL (Akad et al., 2007; Edelbaum et al., 2009; Shepherd et al., 2009; Rana et al., 2012). Moreover, controlling the whitefly vector has also become a major focus of world renowned laboratories to control CLCuD through RNAi (author’s personal communication). These techniques are lagging in “fair control” of CLCuD. All of these techniques were deployed directly or indirectly to control only CABs but not their cognate DNA-satellites. The role of CABs associated DNA-satellites to salvage CABs has been totally ignored during course of these efforts. This scenario has put the scientist in a situation where they plan to deploy more than one strategies (pyramiding) at once, which itself is a very laborious job.

Successful Implications of CRISPR/Cas9 System Against Geminiviruses

CRISPR/Cas9 systems have superiority over other nucleases such as ZFN and TALEN for targeting multiple genes at the same time. There is variety of multiplex models available for genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Either these models involve single RNA Pol-III promotor (Guo et al., 2015) or several different promotors at the same time (Kabadi et al., 2014; Sakuma et al., 2014; Cobb et al., 2015) to drive sgRNA/s co-expression using a single expression vector. Using multiple promoters for sets of sgRNAs in a single vector is very laborious and inconvenient (Guo et al., 2015). The ultimate strategy is to use a single promoter to drive multiple sgRNAs with each of them following a direct repeat (DR) sequence (Cong et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2015), which is very similar to the native strategy in Streptococcus thermophilus involving crRNA interspacers followed by almost similar sized conserved DR sequences (Guo et al., 2015).

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been successfully employed in controlling BeYDV (Baltes et al., 2015), BSCTV (Ji et al., 2015), and TYLCV (Ali et al., 2015). Ji et al. (2015) found that viral load was significantly reduced (up to 97%) using different BSCTV constructs in Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Whereas, Baltes et al. (2015) reported 87% reduction in targeted viral load in N. benthamiana using different sgRNAs from BeYDV, which was further improved by a combination of two sgRNAs together. The strategy involving use of CRISPR/Cas9 mediated resistance against geminiviruses was further extended to TYLCV – a monopartite begomovirus causing yellow leaf curl disease in tomatoes in most of the tomato growing areas of the world (Ali et al., 2015). During their study Ali et al. (2015) found that sgRNA constructs targeting stem loop structure in IR conferred better resistance against TYLCV in N. benthamiana plants. These successful implications suggest that there is huge potential in employing CRISPR/Cas9 system against geminiviruses, thereby targeting several sites in the virus genome (Zlotorynski, 2015).

Proposed Methodology for Designing Multiplex sgRNA to Circumvent CLCUD

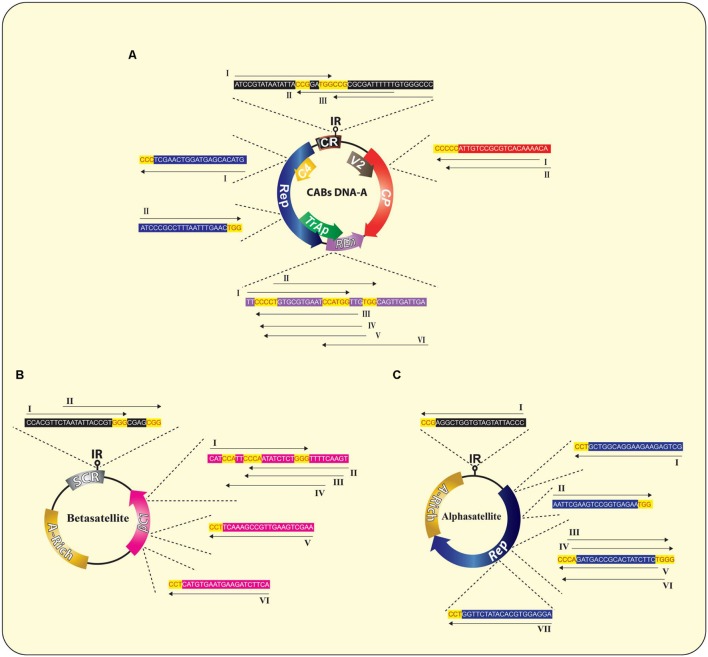

Till now, the CRISPR/Cas9 has been employed against just single species of geminiviruses, as previously mentioned, which limits this technology from reaching its full potential. To maximize the output of this technology, a multiplex type sgRNA could be designed that allow simultaneous editing of multiple begomoviruses in just one go and this is a noteworthy advantage of CRISPR/Cas9 system in comparison to other virus controlling strategies. For effective, rapid and wide-scale control over CABs, here we addressed key considerations for designing multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 system whose applications include, but not circumscribed to, simultaneous targeting of all types of CABs along with their cognate DNA-satellites (present in south east Asia). To achieve an absolute control over such a huge complex demands a multiplex genome editing strategy based on multiplex sgRNA that can potentially target whole CLCuD complex. For the said purpose, full length nucleotide sequences of CABs and their cognate DNA-satellites were retrieved from NCBI databank, aligned in Mega6 (Thompson et al., 1994) and most conserved regions, bearing protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences, were selected to design multiplex sgRNA cassette (Figures 3 and 4). All the designed sgRNAs (16 for CABs, 08 for alphsatellites and 12 for CLCuMuB) were analyzed on the basis of available Arabidopsis genome for specificity, off-targets and quality score (Supplementary Table S1). Analyses showed that the majority of designed sgRNAs have off-target effects, though in non-coding regions, thus posing a major challenge in the course of their successful exploitation. Several strategies have been reported to enhance Cas9 specificity, including use of Cas9 nickase mutant (Mali et al., 2013; Ran et al., 2013), catalytically inactive Cas9 nucleases (Guilinger et al., 2014; Tsai et al., 2014), and few more strategies but with limited applications. Very recently, high-fidelity Cas9 nucleases were developed on the basis of structure-guided protein engineering strategy where a few amino acids were replaced successfully to reduce off-target effects and maintain robust on-target cleavage (Kleinstiver et al., 2016; Slaymaker et al., 2016). Importantly, Baltes et al. (2015) showed that designed sgRNA coupled with catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) could control the BeYDV genome without cleaving the genome, hence, Cas9-HF (Kleinstiver et al., 2016; Slaymaker et al., 2016) or dCas9 (Baltes et al., 2015) could be used to eliminate the off-targets effects. We hereby proposed that same strategy could be employed here to reduce the off-target effects.

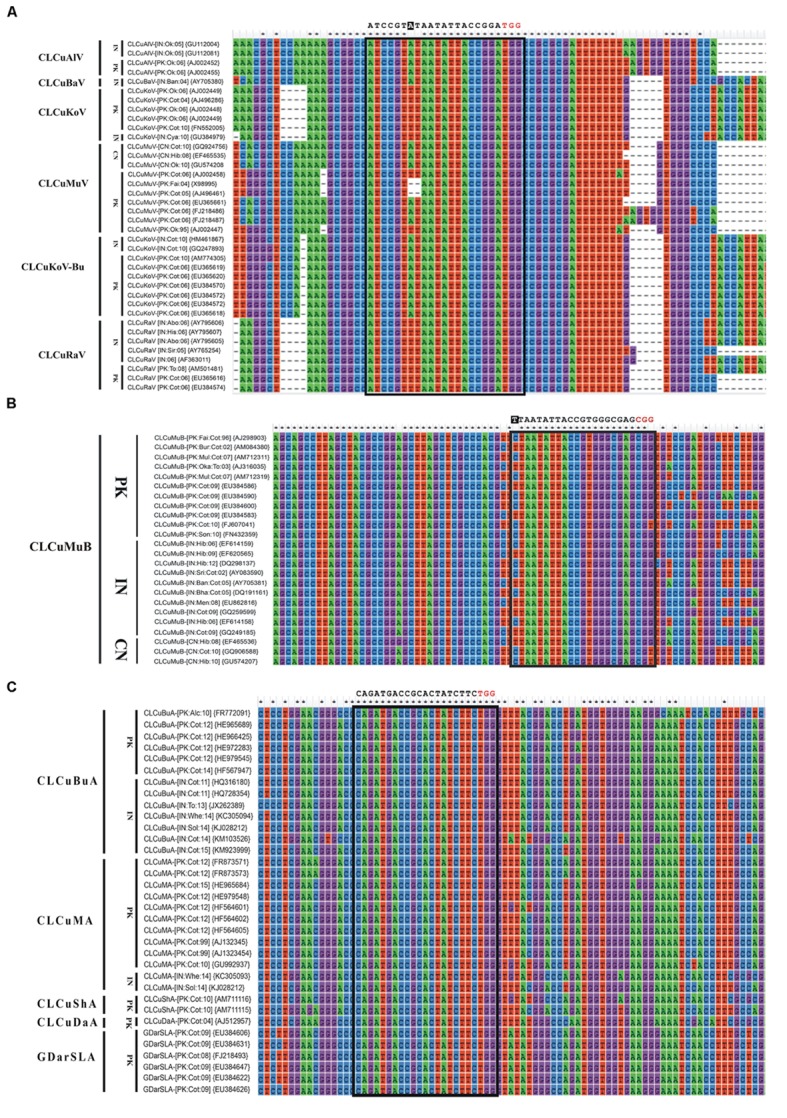

FIGURE 3.

Nucleotide sequence alignments of CABs (A) and their associated DNA-satellites (B,C). All the sequences were retrieved from NCBI GenBank database and aligned using ClustalW in Mega6. The isolate descriptors and accession numbers are given on the left side of each alignment. All the possible sgRNAs are summarized in the Supplementary Table S1. Only the recommended sgRNA sequence is given at the top of each alignment as black text. The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence is indicated in red text. Any mismatch outside of the seed sequence is highlighted as white text with black background.

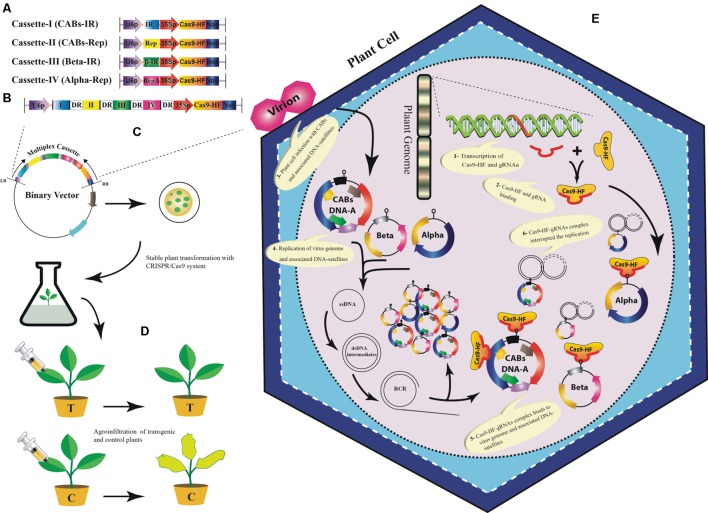

FIGURE 4.

Wild type genome of CABs (A) and associated DNA-satellites (B,C) illustrating the suggested sgRNAs sequences and their corresponding potential targets in each molecule, respectively. The PAM sequences are indicated in red text with yellow background whereas, rest of the sequences are indicated in black text with colored background similar to the respective target gene. All sgRNAs are indicated as unbroken black arrows showing the direction of expression of each sgRNA. A detailed list of all possible sgRNAs is summarized in the Supplementary Table S1.

Our analyses showed that designed sgRNAs targeting IR regions have less off-targets in Arabidopsis genome (Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, it has been proved that sgRNAs targeting IR of geminiviruses confer better resistance as compared to other targeted sgRNAs in a geminivirus genome (Ali et al., 2015; Baltes et al., 2015). Therefore, we proposed a multiplex sgRNA cassette targeting IR and Rep of the CABs, IR of CLCuMuB and Rep of diverse alphasatellites, respectively (Figures 5A,B; Supplementary Table S1). Targeting IR could provide broad-spectrum resistance against these viruses under natural conditions because it is conserved among all members of the plant virus family geminiviridae, hence chance of resistance breaking would be minimized. To assemble such a cassette bearing multiple sgRNAs, many different strategies could be used such as golden gate cloning (Engler et al., 2008; Xing et al., 2014), array assembly (Guo et al., 2015), tRNA processing (Xie et al., 2015), and use of chimeric constructs (Cong et al., 2013). The expression of the gRNA cassette should be driven by single RNA Pol-III promoter and Cas9 may be expressed from CaMV-35S promoter followed by a NOS terminator sequence. Moreover, each sgRNA should be followed by a DR sequence to facilitate homologous recombination (Figure 5B). Finally, the designed cassette could be cloned directly into a binary vector to facilitate Agrobacterium-mediated stable genetic transformation in the model plant N. benthamiana (Figure 5C). The transgenic plants harboring the sgRNA multiplex cassette along with all necessary controls would be challenged by different CABs with and without their cognate DNA-satellites using agroinfiltration (Figure 5D). The control plants will start showing typical CLCuD symptoms after 2–3 weeks of post inoculation. Whereas, the transgenic plants harboring sgRNA multiplex cassette would be symptom free depending upon the level of expression of each sgRNA (Figure 5E). Once proof-of-concept established in N. benthamiana plants then whole system could be tested in the local cotton germplasm such as ‘Cocker’, which is not only susceptible to CLCuD but also easy to transform (Ikram-Ul-Haq, 2004; Sohrab et al., 2014). The plant transformation will be done by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and the fully established transgenic plants will be challenged by viruliferous whiteflies either in the cages or directly exposed to the viral inoculum in the field. The multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 strategy proposed here, could provide a comprehensive approach to control CABs and their associated DNA-satellites simultaneously.

FIGURE 5.

A tentative approach to engineer resistance against CABs and their associated DNA-satellites using CRISPR/Cas9 system. Graphical representation to construct sgRNA cassettes: A uniplex approach to construct individual sgRNAs for IR and Rep of CABs, βC1 of betasatellite and Rep-A of alphasatellite (A), Multiplex approach to construct a joint cassette for IR and Rep (of CABs), βC1 and Rep-A to target CABs, betasatellite and alphasatellite, respectively, (B). All of the sgRNAs are shown to be expressed from common RNA polymerase-III promoter (U6p). Each sgRNA is followed by a DR sequence (rounded rectangle) to ensure homologous recombination. Cas9 may be expressed from CaMV-35S promoter followed by a NOS terminator sequence. The multiplex cassette would be inserted between left- and right border of a suitable binary vector to carry out stable genetic transformation in Nicotiana benthamiana plants (C). The control plants will be transformed with empty binary vector to ensure no resistance against CABs and associated DNA-satellites. The transgenic N. benthamiana plants will be agroinfiltrated with the CABs alone and/or with the associated DNA-satellites (D). The transgenic plants successfully expressing CRISPR/Cas9 would show resistance against the viral complex whereas, the negative control plants will start showing typical CLCuD symptoms. A simultaneous in planta graphical representation of CRISPR/Cas9 system (E): 1- Principle components of CRISPR/Cas9 system are transcribed from the plant genome in transgenic plants. 2- Assemblage of Cas9-HF and sgRNA. 3- Virus infection starts inside the cell after agroinfiltration using Agrobacterium tumefacience. 4- The single stranded DNA (ssDNA) of begomovirus and the associated DNA-satellites start proliferating by rolling circle replication (RCR) via a double stranded (ds) DNA intermediates in an infected plant cell. 5- The sgRNA and Cas9-HF complex bind at the complementary target sites along the dsDNA intermediates. 6- The activated sgRNA complex target the viral genome (s) and produce double-strand break (DSB) that can lead to degradation of viral and satellite genome. However, DSB can be repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair mechanism thus leaving the mutation in viral genome.

Conclusion

Development of resistance against CLCuD is an intricate practice amenable to be overcome by counter strategies adopted by either the CABs or associated DNA-satellites. Offering resistance through conventional as well as other synthetic biology approaches is genetically tractable through molecular genetics but the history showed that the resistance, once achieved, was not long-lasting. Alternatively, we have to devise a multifaceted strategy, which could provide unusually precise and specific approach to counter CLCuD-complex. CRISPR/Cas9 system offers a flexible approach for stacking multiple nucleases as one transgene, thereby offering targeted cleavage of mixed infections by multiple viruses and associated DNA-satellites, such as CLCuD-complex. The CRISPR/Cas9 system could be an answer to open up unprecedented possibilities to develop CLCuD resistant cotton plants. Thus, it could be beneficial to the scientific community in devising future resistance strategies against whole CLCuD complex and this approach will be an outstanding example.

Author Contributions

ZI conceived the idea, performed the bioinformatics analysis for designed sgRNAs and drafted the first draft of the manuscript. MNS designed all the sgRNAs, draw figures and helped in preparation of first draft of the manuscript. MS drew all tables, searched all the web based tools and helped in preparation of first draft of the manuscript. First draft of the manuscript was edited and approved by all authors.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Dr. Thomas Martin, Uppsala University, Sweden for valuable suggestions, and critically reading this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.00475

References

- Ahmad S., Islam N., Mahmood A., Ashraf F., Hayat K., Hanif M. (2010). Screening of cotton germplasm against Cotton leaf curl virus. Pak. J. Bot. 42 3327–3342. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S., Mahmood K., Hanif M., Nazeer W., Malik W., Qayyum A., et al. (2011). Introgression of cotton leaf curl virus-resistant genes from Asiatic cotton (Gossypium arboreum) into upland cotton (G. hirsutum). Genet. Mol. Res. 10 2404–2414. 10.4238/2011.October.7.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akad F., Eybishtz A., Edelbaum D., Gorovits R., Dar-Issa O., Iraki N., et al. (2007). Making a friend from a foe: expressing a GroEL gene from the whitefly Bemisia tabaci in the phloem of tomato plants confers resistance to Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Arch. Virol. 152 1323–1339. 10.1007/s00705-007-0942-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar K. P., Khan M. K. R., Ahmad M., Sarwar N., Ditta A. (2010). Partial resistance of a cotton mutant to Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus. Span. J. Agric. Res. 8 1098–1104. 10.1007/s00705-012-1225-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali I., Amin I., Briddon R., Mansoor S. (2013). Artificial microRNA-mediated resistance against the monopartite Begomovirus Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus. Virol. J. 10 231 10.1186/1743-422X-10-231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M. (1997). Breeding of cotton varieties for resistance to cotton leaf curl virus. Pak. J. Phytopathol. 9 1–7. 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.12.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali Z., Abulfaraj A., Idris A., Ali S., Tashkandi M., Mahfouz M. (2015). CRISPR/Cas9-mediated viral interference in plants. Genome Biol. 16 238 10.1186/s13059-015-0799-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin I., Patil B. L., Briddon R. W., Mansoor S., Fauquet C. M. (2011). Comparison of phenotypes produced in response to transient expression of genes encoded by four distinct Begomoviruses in Nicotiana benthamiana and their correlation with the levels of developmental miRNAs. Virol. J. 8 238 10.1186/1743-422X-8-238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amudha J., Balasubramani G., Malathi V., Monga D., Bansal K., Kranthi K. (2010). Cotton transgenics with Antisense AC1 gene for resistance against cotton leaf curl virus. Electronic J. Plant Breed. 1 360–369. [Google Scholar]

- Amudha J., Balasubramani G., Malathi V. G., Monga D., Kranthi K. R. (2011). Cotton leaf curl virus resistance transgenics with antisense coat protein gene (AV1). Curr. Sci. 101 300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Aragão F. J. L., Faria J. C. (2009). First transgenic geminivirus-resistant plant in the field. Nat. Biotechnol. 27 1086–1088. 10.1038/nbt1209-1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asad S., Haris W., Bashir A., Zafar Y., Malik K., Malik N., et al. (2003). Transgenic tobacco expressing geminiviral RNAs are resistant to the serious viral pathogen causing cotton leaf curl disease. Arch. Virol. 148 2341–2352. 10.1007/s00705-003-0179-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes N. J., Hummel A. W., Konecna E., Cegan R., Bruns A. N., Bisaro D. M., et al. (2015). Conferring resistance to geminiviruses with the CRISPR–Cas prokaryotic immune system. Nat. Plants 1 15145 10.1038/nplants.2015.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaya D., Davison M., Barrangou R. (2011). CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and archaea: versatile small RNAs for adaptive defense and regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45 273–297. 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolotin A., Quinquis B., Sorokin A., Ehrlich S. D. (2005). Clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPRs) have spacers of extrachromosomal origin. Microbiology 151 2551–2561. 10.1099/mic.0.28048-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher B., Unseld S., Ceulemans H., Russell R. B., Jeske H. (2004). Geminate structures of African cassava mosaic virus. J. Virol. 78 6758–6765. 10.1128/JVI.78.13.6758-6765.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon R. W. (2003). Cotton leaf curl disease, a multicomponent Begomovirus complex. Mol. Plant Pathol. 4 427–434. 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon R. W., Bull S. E., Amin I., Mansoor S., Bedford I. D., Rishi N., et al. (2004). Diversity of DNA 1; a satellite-like molecule associated with monopartite Begomovirus-DNA β complexes. Virology 324 462–474. 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon R. W., Mansoor S., Bedford I. D., Pinner M. S., Saunders K., Stanley J., et al. (2001). Identification of DNA components required for induction of cotton leaf curl disease. Virology 285 234–243. 10.1006/viro.2001.0949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon R. W., Markham P. G. (2001). Cotton leaf curl virus disease. Virus Res. 71 151–159. 10.1016/S0168-1702(00)00195-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J., Zerbini F. M., Navas-Castillo J., Moriones E., Ramos-Sobrinho R., Silva J. F., et al. (2015). Revision of Begomovirus taxonomy based on pairwise sequence comparisons. Arch. Virol. 160 1593–1619. 10.1007/s00705-015-2398-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Wang X., Wu J., Briddon R. W., Zhou X. (2011). βC1 encoded by tomato yellow leaf curl China betasatellite forms multimeric complexes in vitro and in vivo. Virology 409 156–162. 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb R. E., Wang Y., Zhao H. (2015). High-efficiency multiplex genome editing of Streptomyces species using an engineered CRISPR/Cas system. ACS Synth. Biol. 4 723–728. 10.1021/sb500351f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., et al. (2013). Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339 819–823. 10.1126/science.1231143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X., Li G., Wang D., Hu D., Zhou X. (2005). A Begomovirus DNAβ-encoded protein binds DNA, functions as a suppressor of RNA silencing, and targets the cell nucleus. J. Virol. 79 10764–10775. 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10764-10775.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench J. G., Hartenian E., Graham D. B., Tothova Z., Hegde M., Smith I., et al. (2014). Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat. Biotechnol. 32 1262–1267. 10.1038/nbt.3026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelbaum D., Gorovits R., Sasaki S., Ikegami M., Czosnek H. (2009). Expressing a whitefly GroEL protein in Nicotiana benthamiana plants confers tolerance to tomato yellow leaf curl virus and cucumber mosaic virus, but not to grapevine virus A or tobacco mosaic virus. Arch. Virol. 154 399–407. 10.1007/s00705-009-0317-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler C., Kandzia R., Marillonnet S. (2008). A one pot, one step, precision cloning method with high throughput capability. PLoS ONE 3:e3647 10.1371/journal.pone.0003647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq A., Farooq J., Mahmood A., Batool A., Rehman A., Shakeel A., et al. (2011). An overview of cotton leaf curl virus disease (CLCuD) a serious threat to cotton productivity. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 5 1823–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z., Zhang B., Ding W., Liu X., Yang D.-L., Wei P., et al. (2013). Efficient genome editing in plants using a CRISPR/Cas system. Cell Res. 23 1229–1232. 10.1038/cr.2013.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilinger J. P., Thompson D. B., Liu D. R. (2014). Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nat. Biotechnol. 32 577–582. 10.1038/nbt.2909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Xu K., Liu Z., Zhang C., Xin Y., Zhang Z. (2015). Assembling the Streptococcus thermophilus clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) array for multiplex DNA targeting. Anal. Biochem. 478 131–133. 10.1016/j.ab.2015.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley-Bowdoin L., Settlage S. B., Robertson D. (2004). Reprogramming plant gene expression: a prerequisite to geminivirus DNA replication. Mol. Plant Pathol. 5 149–156. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2004.00214.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heigwer F., Kerr G., Boutros M. (2014). E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nat. Methods 11 122–123. 10.1038/nmeth.2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. D., Scott D. A., Weinstein J. A., Ran F. A., Konermann S., Agarwala V., et al. (2013). DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 827–832. 10.1038/nbt.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M., Mansoor S., Iram S., Zafar Y., Briddon R. W. (2007). The hypersensitive response to tomato leaf curl New Delhi virus nuclear shuttle protein is inhibited by transcriptional activator protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20 1581–1588. 10.1094/MPMI-20-12-1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain T., Ali M. (1975). A review of cotton diseases of Pakistan. Pak. Cottons 19 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ikram-Ul-Haq (2004). Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) via vacuum infiltration. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 22 279–288. 10.1007/BF02773138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilardi V., Tavazza M. (2015). Biotechnological strategies and tools for Plum pox virus resistance: trans-, intra-, cis-genesis and beyond. Front. Plant Sci. 6:379 10.3389/fpls.2015.00379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal M. J., Reddy O. U. K., El-Zik K. M., Pepper A. E. (2001). A genetic bottleneck in the ‘evolution under domestication’ of upland cotton Gossypium hirsutum L. examined using DNA fingerprinting. Theor. Appl. Genet. 103 547–554. 10.1007/PL00002908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Z., Sattar M. N., Kvarnheden A., Mansoor S., Briddon R. W. (2012). Effects of the mutation of selected genes of Cotton leaf curl Kokhran virus on infectivity, symptoms and the maintenance of Cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite. Virus Res. 169 107–116. 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X., Zhang H., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Gao C. (2015). Establishing a CRISPR–Cas-like immune system conferring DNA virus resistance in plants. Nat. Plants 1 15144 10.1038/nplants.2015.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Bikard D., Cox D., Zhang F., Marraffini L. A. (2013). RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 233–239. 10.1038/nbt.2508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., Charpentier E. (2012). A programmable dual-RNA–guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337 816–821. 10.1126/science.1225829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabadi A. M., Ousterout D. G., Hilton I. B., Gersbach C. A. (2014). Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-based genome engineering from a single lentiviral vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:e147 10.1093/nar/gku749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirthi N., Priyadarshini C. G. P., Sharma P., Maiya S. P., Hemalatha V., Sivaraman P., et al. (2004). Genetic variability of Begomoviruses associated with cotton leaf curl disease originating from India. Arch. Virol. 149 2047–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinstiver B. P., Pattanayak V., Prew M. S., Tsai S. Q., Nguyen N. T., Zheng Z., et al. (2016). High-fidelity CRISPR–Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature 529 490–495. 10.1038/nature16526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Kumar J., Khan J. (2010). Sequence characterization of cotton leaf curl virus from Rajasthan: phylogenetic relationship with other members of geminiviruses and detection of recombination. Virus Gen. 40 282–289. 10.1007/s11262-009-0439-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J., Gunapati S., Alok A., Lalit A., Gadre R., Sharma N., et al. (2015). Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus with intact or mutant transcriptional activator proteins: complexity of cotton leaf curl disease. Arch. Virol. 160 1219–1228. 10.1007/s00705-015-2384-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.-F., Norville J. E., Aach J., McCormack M., Zhang D., Bush J., et al. (2013). Multiplex and homologous recombination-mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 688–691. 10.1038/nbt.2654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Robinson D. J., Harrison B. D. (1998). Defective forms of cotton leaf curl virus DNA-A that have different combinations of sequence deletion, duplication, inversion and rearrangement. J. Gen. Virol. 79 1501–1508. 10.1099/0022-1317-79-6-1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood T., Arshad M., Gill M. I., Mahmood H. T. (2003). Burewala strain of cotton leaf curl virus: a threat to CLCuV cotton resistant varieties. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2 968–970. 10.3923/ajps.2003.968.970 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P., Aach J., Stranges P. B., Esvelt K. M., Moosburner M., Kosuri S., et al. (2013). CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 833–838. 10.1038/nbt.2675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor S., Amin I., Hussain M., Zafar Y., Bull S., Briddon R. W., et al. (2001). Association of a disease complex involving a Begomovirus, DNA 1 and a distinct DNA beta with leaf curl disease of okra in Pakistan. Plant Dis. 85 922 10.3390/v5092116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor S., Amin I., Iram S., Hussain M., Zafar Y., Malik K. A., et al. (2003). Breakdown of resistance in cotton to cotton leaf curl disease in Pakistan. Plant Pathol. 52 784 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2003.00893.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montague T. G., Cruz J. M., Gagnon J. A., Church G. M., Valen E. (2014). CHOPCHOP: a CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 W401–W407. 10.1093/nar/gku410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubin M., Amin I., Amrao L., Briddon R. W., Mansoor S. (2010). The hypersensitive response induced by the V2 protein of a monopartite Begomovirus is countered by the C2 protein. Mol. Plant Pathol. 11 245–254. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00601.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubin M., Hussain M., Briddon R. W., Mansoor S. (2011). Selection of target sequences as well as sequence identity determine the outcome of RNAi approach for resistance against cotton leaf curl geminivirus complex. Virol. J. 8 122 10.1186/1743-422X-8-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qazi J., Amin I., Mansoor S., Iqbal J., Briddon R. W. (2007). Contribution of the satellite encoded gene βC1 to cotton leaf curl disease symptoms. Virus Res. 128 135–139. 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman H. (1997). Breeding Approaches to Cotton Leaf Curl Resistance. The ICAC RECORDER, Vol. XV Washington, DC: International Cotton Advisory Committee, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M., Zafar Y. (2007). Registration of NIBGE-115 cotton. J. Plant Regist. 1 51–52. 10.3198/jpr2006.12.0778crg [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan P., Naik A., Katturi P., Kurulekar M., Kankanallu R., Anandalakshmi R. (2012). Dominance of resistance-breaking Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus (CLCuBuV) in northwestern India. Arch. Virol. 157 855–868. 10.1007/s00705-012-1225-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran F. A., Hsu P. D., Lin C.-Y., Gootenberg J. S., Konermann S., Trevino A. E., et al. (2013). Double nicking by RNA-Guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell 154 1380–1389. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana V. S., Singh S. T., Priya N. G., Kumar J., Rajagopal R. (2012). Arsenophonus GroEL interacts with CLCuV and is localized in midgut and salivary gland of whitefly B. tabaci. PLoS ONE 7:e42168 10.1371/journal.pone.0042168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas M. R., Jiang H., Salati R., Xoconostle-Cázares B., Sudarshana M. R., Lucas W. J., et al. (2001). Functional analysis of proteins involved in movement of the monopartite Begomovirus, Tomato yellow leaf curl virus. Virology 291 110–125. 10.1006/viro.2001.1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed M., Behjatnia S. A. A., Mansoor S., Zafar Y., Hasnain S., Rezaian M. A. (2005). A single complementary-sense transcript of a geminiviral DNA β satellite is determinant of pathogenicity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18 7–14. 10.1094/MPMI-18-0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed M., Mansoor S., Rezaian M. A., Briddon R. W., Randles J. W. (2008). Satellite DNA β overrides the pathogenicity phenotype of the C4 gene of Tomato leaf curl virus, but does not compensate for loss of function of the coat protein and V2 genes. Arch. Virol. 153 1367–1372. 10.1007/s00705-008-0124-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed M., Zafar Y., Randles J. W., Rezaian M. A. (2007). A monopartite begomovirus-associated DNA β satellite substitutes for the DNA B of a bipartite begomovirus to permit systemic infection J. Gen. Virol. 88 2881–2889. 10.1099/vir.0.83049-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma T., Nishikawa A., Kume S., Chayama K., Yamamoto T. (2014). Multiplex genome engineering in human cells using all-in-one CRISPR/Cas9 vector system. Sci. Rep. 4 1–6. 10.1038/srep05400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjaya, Satyavathi V. V., Prasad V., Kirthi N., Maiya S. P., Savithri H. S., et al. (2005). Development of cotton transgenics with antisense AV2 gene for resistance against cotton leaf curl virus (CLCuD) via Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 81 55–63. 10.1007/s11240-004-2777-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sattar M. N., Kvarnheden A., Saeed M., Briddon R. W. (2013). Cotton leaf curl disease – an emerging threat to cotton production worldwide. J. Gen. Virol. 94 695–710. 10.1099/vir.0.049627-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settlage S. B., See R. G., Hanley-Bowdoin L. (2005). Geminivirus C3 protein: replication enhancement and protein interactions. J. Virol. 79 9885–9895. 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9885-9895.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd D. N., Martin D. P., Thomson J. A. (2009). Transgenic strategies for developing crops resistant to geminiviruses. Plant Sci. 176 1–11. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.08.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shuja M. N., Briddon R. W., Tahir M. (2014). Identification of a distinct strain of Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus. Arch. Virol. 159 2787–2790. 10.1007/s00705-014-2097-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddig M. A. (1970). “Breeding for leaf curl resistance in Sakel cotton,” in Cotton Growth in the Gezira Environment, eds Siddig M. A., Hughes L. C. (Wad Madani: Agricultural Research Cororation; ), 153. [Google Scholar]

- Slaymaker I. M., Gao L., Zetsche B., Scott D. A., Yan W. X., Zhang F. (2016). Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science 351 84–88. 10.1126/science.aad5227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohrab S. S., Kamal M. A., Ilah A., Husen A., Bhattacharya P. S., Rana D. (2014). Development of Cotton leaf curl virus resistant transgenic cotton using antisense ßC1 gene. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 22 279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunitha S., Shanmugapriya G., Balamani V., Veluthambi K. (2013). Mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV) AC4 suppresses post-transcriptional gene silencing and an AC4 hairpin RNA gene reduces MYMV DNA accumulation in transgenic tobacco. Virus Genes 46 496–504. 10.1007/s11262-013-0889-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir M. N. (2014). Use of Amplicon-Based System for Enhanced Resistance against Cotton Leaf Curl Disease. Ph.D. thesis, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai S. Q., Wyvekens N., Khayter C., Foden J. A., Thapar V., Reyon D., et al. (2014). Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 32 569–576. 10.1038/nbt.2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanitharani R., Chellappan P., Pita J. S., Fauquet C. M. (2004). Differential roles of AC2 and AC4 of cassava geminiviruses in mediating synergism and suppression of posttranscriptional gene silencing. J. Virol. 78 9487–9498. 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9487-9498.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma A., Malathi V. G. (2003). Emerging geminivirus problems: a serious threat to crop production. Ann. Appl. Biol. 142 145–164. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2003.tb00240.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Tang Y., Lu J., Shao Y., Qin X., Li Y., et al. (2016). Characterization of novel cytochrome P450 2E1 knockout rat model generated by CRISPR/Cas9. Biochem. Pharmacol. 105 80–90. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao A., Cheng Z., Kong L., Zhu Z., Lin S., Gao G., et al. (2014). CasOT: a genome-wide Cas9/gRNA off-target searching tool. Bioinformatics 30 1180–1182. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K., Minkenberg B., Yang Y. (2015). Boosting CRISPR/Cas9 multiplex editing capability with the endogenous tRNA-processing system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 3570–3575. 10.1073/pnas.1420294112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie K., Zhang J., Yang Y. (2014). Genome-wide prediction of highly specific guide RNA spacers for CRISPR–Cas9-mediated genome editing in model plants and major crops. Mol. Plant 7 923–926. 10.1093/mp/ssu009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing H.-L., Dong L., Wang Z.-P., Zhang H.-Y., Han C.-Y., Liu B., et al. (2014). A CRISPR/Cas9 toolkit for multiplex genome editing in plants. BMC Plant Biol. 14:327 10.1186/s12870-014-0327-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Baliji S., Buchmann R. C., Wang H., Lindbo J. A., Sunter G., et al. (2007). Functional modulation of the geminivirus AL2 transcription factor and silencing suppressor by self-interaction. J. Virol. 81 11972–11981. 10.1128/JVI.00617-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf S., Rasool G., Amin I., Mansoor S., Saeed M. (2013). Interference of a synthetic rep protein to develop resistance against cotton leaf curl disease. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 15 1140–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Zaffalon V., Mukherjee S., Reddy V., Thompson J., Tepfer M. (2012). A survey of geminiviruses and associated satellite DNAs in the cotton-growing areas of northwestern India. Arch. Virol. 157 483–495. 10.1007/s00705-011-1201-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Luan J. B., Qi J. F., Huang C. J., Li M., Zhou X. P., et al. (2012). Begomovirus–whitefly mutualism is achieved through repression of plant defences by a virus pathogenicity factor. Mol. Ecol. 21 1294–1304. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Liu Y., Robinson D. J., Harrison B. D. (1998). Four DNA-A variants among Pakistani isolates of cotton leaf curl virus and their affinities to DNA-A of geminivirus isolates from okra. J. Gen. Virol. 79 915–923. 10.1099/0022-1317-79-4-915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotorynski E. (2015). Plant cell biology: CRISPR-Cas protection from plant viruses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16 642–642. 10.1038/nrm4079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.