ABSTRACT

Mental health problems continue to be a significant comorbidity for people with HIV infection, even in the era of effective antiretroviral therapy. Here, we report on the changes in the mental health diagnoses based on clinical case reports amongst people with HIV referred to a specialist psychological medicine department over a 24-year period, which include the relative increase in depressive and anxiety disorders, often of a chronic nature, together with a decline in acute mental health syndromes, mania, and organic brain disorders. In addition, new challenges, like the presence of HIV and Hepatitis C co-infection, and the new problems created by recreational drugs, confirm the need for mental health services to be closely involved with the general medical services. A substantial proportion of people with HIV referred to specialist services suffer complex difficulties, which often require the collaboration of both psychiatrists and psychologists to deal effectively with their difficulties.

KEYWORDS: Psychiatry, psychology, HIV, recreational drugs, Hepatitis C

Introduction

It has been recognised since early in the epidemic that those living with HIV/AIDS suffer significant psychosocial sequelae (Catalan, Burgess, & Klimes, 1995; Catalan, Meadows, & Douzenis, 2000; Citron, Brouillette, & Beckett, 2005). Psychological morbidity has changed with the introduction of HART (Catalan et al., 2000), and recent reviews from Canada (Kendall et al., 2014) and Australia (Edmiston, Passmore, Smith, & Petoumenos, 2015) confirm that mental health problems remain the most common comorbidities in HIV. The Psychological Medicine Unit, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London, established in 1989, has a multidisciplinary mental health team that works closely with the specialist HIV medical and nursing teams. An earlier publication reported some of the changes that occurred in the first 10 years, which included the introduction of effective antiretroviral treatments (Catalan et al., 2000). Here, we extend the period of monitoring of mental health diagnoses in people with HIV referred to the service up to the end of 2014, providing a longitudinal view covering from 1999 to 2014.

In addition, and for 2014 alone, we have provided information for the mental health problems of people with hepatitis co-infection, recreational drug use, and patients needing the simultaneous involvement of psychiatrists and psychologists.

Aims

The aims of this study are: (a) to report on the number and mental health diagnoses of people with HIV referred to the Unit in 1990, 1995, 1999, 2005, and 2014; (b) for 2014 alone, to report on the mental health diagnoses of people with both HIV and Hepatitis C infection, and those using recreational drugs; (c) for 2014 alone, to report on the diagnoses of people receiving help from both psychologists and psychiatrists (“complex patients”).

Methods

Data were collected about all new HIV referrals at each index year. Details about each referral identified as HIV positive from the paper records were then extracted from the confidential electronic database. Mental Health diagnosis was based on ICD-10. The medical teams referred patients, urgently and non-urgently, attending their clinics as outpatients and medical inpatients. Patients agreed to the documentation of their diagnosis and other data, and their anonymised use for research purposes.

Results

Number of patients seen with HIV

A total of 490 patients were referred during 2014, with a mean age of 43 and a sex ratio of 11:1 (M:F). The number of patients referred to the service has consistently increased from 123 in 1990 to 490 in 2014, and the trend of increasing numbers of referrals has been seen at each data collection point (Table 1).

Table 1. Principal psychiatric diagnosis.

| 1990 | 1995 | 1999 | 2005 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 21 (20%) | 59 (33%) | 98 (34%) | 162 (45%) | 186 (47%) |

| Anxiety disorder | 6 (6%) | 35 (20%) | 48 (16%) | 50 (14%) | 60 (15%) |

| Adjustment disorder | 33 (32%) | 25 (14%) | 44 (15%) | 53 (15%) | 65 (17%) |

| Sexual dysfunction | 1 (1%) | 5 (3%) | 46 (16%) | 56 (16%) | 11 (3%) |

| Substance misuse | 21 (20%) | 22 (12%) | 32 (11%) | 20 (6%) | 36 (9%) |

| Acute organic | 5 (5%) | 5 (3%) | 14 (5%) | 4 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Chronic organic | 11 (11%) | 18 (10%) | 6 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 15 (4%) |

| Mania | 4 (4%) | 7 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (2%) | 5 (1%) |

| Schizophreniform | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 5 (1%) |

| Personality disorder | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (2%) |

| DNA | 20 | 128 | 68 | 45 | 98 |

| Patients assessed (N) | 103 | 178 | 292 | 361 | 392 |

| Total referrals | 123 | 306 | 360 | 406 | 490 |

Principal psychiatric diagnosis

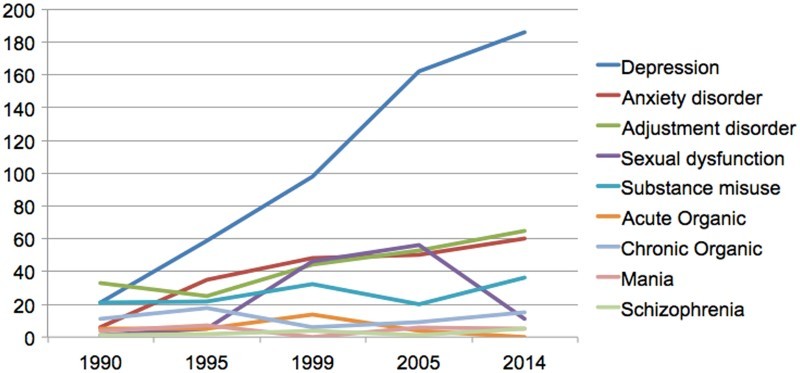

In 2014, the most common diagnosis of patients assessed was depression, with this being the principal diagnosis in 186 (47%) of those assessed, the highest percentage since data were collected. The diagnosis of anxiety disorder has also increased from 6 (6%) in 1990 to 60 (15%) in 2014. Over this time, there has been a reduction in the diagnosis of adjustment disorder, substance misuse as a principal diagnosis, acute and chronic organic brain illness and manic disorders (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Change in number of diagnoses over time.

Hepatitis C infection

The number of patients referred in 2014 co-infected with HIV and Hepatitis C was 34 (9%). The principal psychiatric diagnosis was depression in 16 (47%) of patients, anxiety disorder in 6 (18%), and adjustment disorder in 4 (12%) (see Table 2). This is comparable to the principal diagnoses of patients without Hepatitis C. In both the group with Hepatitis C and the group without, 9% had a principal diagnosis of substance misuse. Rates of Hepatitis C co-infection were not collected prior to 2014, so it is not possible to determine if there have been changes over time.

Table 2. Hepatitis C status and principal psychiatric diagnosis.

| Hepatitis C, n = 34 (%) | Patients without Hepatitis C, n = 358 (%) | Total sample, n = 392 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 16 (47) | 170 (47) | 186 (47) |

| Anxiety disorder | 6 (18) | 54 (15) | 60 (15) |

| Adjustment disorder | 4 (12) | 61 (17) | 65 (17) |

| Sexual dysfunction | 1 (3) | 10 (3) | 11 (3) |

| Substance misuse | 3 (9) | 33 (9) | 36 (9) |

| Acute organic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic organic | 1 (3) | 14 (4) | 15 (4) |

| Mania | 1 (3) | 4 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Schizophrenia | 1 (3) | 4 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Personality disorder | 1 (3) | 8 (2) | 9 (2) |

Recreational drug use

In 2014, 30% (116) of referred patients admitted to use of recreational substances and a third of these had substance misuse as their principal diagnosis. The mean age of this group is 39, younger than the average referral to the service of 43. Many of the patients were using multiple substances and it was not possible to distinguish which was the principal drug of use (Table 3).

Table 3. Substances used.

| Substance | Number of users, n = 230 |

|---|---|

| Crystal methamphetamine | 43 (19) |

| Mephedrone | 48 (21) |

| γ-Butyrolactone | 45 (20) |

| Cannabis | 28 (12) |

| Cocaine | 19 (8) |

| LSD/Ecstacy | 7 (3) |

| Heroin | 3 (1) |

| Alcohol | 23 (10) |

| Benzodiazepines | 4 (2) |

| Ketamine | 7 (3) |

| Steroids | 3 (1) |

Patients with complex problems

One hundred and seventy-four (44%) patients seen in 2014 were treated by both psychiatrists and psychologists (“complex group”), while 138 (35%) were seen only by psychologists, and 80 (20%) were seen only by psychiatrists. Depression was the most common diagnosis in all groups (see Table 4). Anxiety disorder was the principal diagnosis of 6 (8%) patients seen by psychiatry, 28 (16%) of the complex group and 26 (19%) patients in the psychology group. Thirty-six (26%) patients seen by psychology had a principal diagnosis of adjustment disorder, compared to 9 (11%) seen by psychiatry and 20 (11%) of the complex group having this principal diagnosis. Sexual dysfunction was not the principal diagnosis of any patients seen by psychology, but was for 7 (9%) patients seen by psychiatry.

Table 4. Diagnoses in complex cases.

| Psychiatry, n = 80 | Psychology, n = 138 | Complex cases, n = 174 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 43 (54) | 52 (38) | 91 (52) |

| Anxiety disorders | 6 (8) | 26 (19) | 28 (16) |

| Adjustment disorders | 9 (11) | 36 (26) | 20 (11) |

| Sexual dysfunction | 7 (9) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) |

| Substance misuse | 9 (11) | 12 (9) | 15 (9) |

| Organic acute | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Organic chronic | 1 (1) | 9 (7) | 5 (3) |

| Mania | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Schizophrenia | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Personality disorders | 2 (3) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) |

Discussion

HIV and mental health

Our results, covering more than 20 years of monitoring of referrals to a dedicated mental health service, show the continued presence of mental health problems in people living with HIV. Despite HIV treatment resulting in better prognosis and campaigns aimed at reducing stigma amongst the general population, people living with HIV commonly experience mental health difficulties. The data show a steadily increasing demand to our service. While such an increase in referrals may reflect both an increase in the number of people with HIV infection attending the hospital, and an increased awareness by clinicians of the presence of mental health problems in this group of patients, the continuing request for mental health assessment and intervention indicates that mental health difficulties remain a major part of the HIV morbidity (Edmiston et al., 2015; Kendall et al., 2014).

The most striking change over time is the steady increase in the diagnoses of depressive and anxiety disorders, with a decline in the diagnoses of adjustment disorders, mania, and organic brain syndromes. It is likely that the process of normalisation of HIV infection and the recognition of the better clinical outcomes have led to the decline in adjustment disorders, while the introduction of effective treatments has played a significant part in the lower frequency of organic brain syndromes and mania. In contrast, depressive and anxiety disorders, often involving a combination of current difficulties and unresolved earlier problems, against a background of social problems, have become more prevalent (Catalan et al., 2000).

New challenges of Hepatitis C co-infection and recreational drugs

New challenges appear with the presence of Hepatitis C co-infection, and the problem of recreational drug use. While patients with a dual diagnosis of HIV and Hepatitis C represent a minority of patients referred to the service, their problems and diagnoses are comparable to the rest of the service with many reporting feelings of stigma comparable to and at times worse than those generated by HIV infection. Recognition of mental health problems in co-infected individuals and referral will be necessary in such cases during treatment for Hepatitis C (Schaefer et al., 2012; Silberbogen, Ulloa, Janke, & Mori, 2009).

Recreational drug use is widespread in patients living with HIV (Colfax & Shoptaw, 2005; Green & Halkitis, 2006; Hirschfield, Remien, Humberstone, Walavalkar, & Chiasson, 2004), and it is often difficult to establish whether the mental health problems are predominantly related to HIV or due to pre-existing problems associated with drug use and lifestyle (Citron et al., 2005; Cohen & Gorman, 2008). The type of recreational drugs use is also changing over time, in particular the rapidly evolving trends of club drugs and “chemsex” present a major problem (Guss, 2000; Semple, Zians, Strathdee, & Paterson, 2009).

Patients with complex problems

For some, single-approach interventions may not fully resolve their difficulties. There is good evidence for the efficacy of interventions for treatment of depression and anxiety disorders in this patient group (Chesney, Chambers, Taylor, Johnson, & Folkman, 2003; Clucas et al., 2011; Olatunji, Mimiaga, O'Cleirigh, & Safren, 2006; Sherr, Clucas, Harding, Sibley, & Catalan, 2011), and it is therefore important to identify and treat them using well-established treatment guidelines, which frequently include psychological interventions alongside psychotropic medications. Delivering such complex treatments employing professionals from two distinct disciplines requires careful thought and coordination.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Catalan J., Burgess A., Klimes I. Psychological medicine of HIV infection. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Catalan J., Meadows J., Douzenis A. The changing pattern of mental health problems in HIV infection: The view from London, UK. AIDS Care. 2000;(3):333–341. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney M. A., Chambers D. B., Taylor J. M., Johnson L. M., Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: Results from a randomised clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003:1038–1046. doi: 10.1097/01.PSY.0000097344.78697.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citron K., Brouillette M.-J., Beckett A., editors. HIV and psychiatry. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clucas C., Sibley E., Harding R., Liu L., Catalan J., Sherr L. A systematic review of interventions for anxiety in people with HIV. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;(5):528–547. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.579989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M. A., Gorman J. M. Comprehensive textbook of AIDS psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G., Shoptaw S. The methamphetamine epidemic: Implications for HIV prevention and treatment. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2005:194–199. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmiston N., Passmore E., Smith D. J., Petoumenos K. Multimorbidity among people with HIV in regional New South Wales, Australia. Sex Health. 2015 doi: 10.1071/SH14070. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Green A., Halkitis P. Crystal methamphetamine and sexual sociality in an urban ay subculture: An elective affinity. Cultural Health and Sex. 2006;(4):317–333. doi: 10.1080/13691050600783320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guss J. Sex like you can't even imagine: “Crystal”, crack, and gay men. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy. 2000;(4):105–122. doi: 10.1300/J236v03n03_09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfield S., Remien R., Humberstone M., Walavalkar I., Chiasson M. Substance use and high risk sex among men who have sex with men: A national online study in the USA. AIDS Care. 2004;(8):1036–1047. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall C. E., Wong J., Taljaard M., Glazier R. H., Hogg W., Younger J., Manuel D. G. A cross-sectional, population-based study measuring comorbidity among people living with HIV in Ontario. BMC Public Health. 2014:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji B., Mimiaga M., O'Cleirigh C., Safren S. Review of treatment studies in depression in HIV. Topics in HIV Medicine. 2006;(3):112–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M., Capuron L., Friebe A., Diez-Quevedo C., Robaeys G., Neri S., Pariante C. Hepatitis C infection, antiretroviral treatment and mental health: A European expert consensus statement. Journal of Hepatology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple S., Zians J., Strathdee S., Paterson T. Sexual marathons and methamphetamine use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009:583–590. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr L., Clucas C., Harding R., Sibley E., Catalan J. HIV and depression – a systematic review of interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;(5):493–527. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.579990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberbogen A., Ulloa E., Janke E., Mori D. Psychosocial issues and mental health treatment recommendations for patients with hepatitis C. Psychosomatics. 2009;(2):114–122. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]