ABSTRACT

In the era of widespread access to antiretroviral therapy, people living with HIV survive; however, this comes with new experiences of comorbidities and HIV-related disability posing new challenges to rehabilitation professionals and an already fragile health system in Southern Africa. Public health approaches to HIV need to include not only prevention, treatment and support but also rehabilitation. While some well-resourced countries have developed rehabilitation approaches for HIV, resource-poor settings of Southern Africa lack a model of care that includes rehabilitation approaches providing accessible and comprehensive care for people living with HIV. In this study, a learning in action approach was used to conceptualize a comprehensive model of care that addresses HIV-related disability and a feasible rehabilitation framework for resource-poor settings. The study used qualitative methods in the form of a focus group discussion with thirty participants including people living with HIV, the multidisciplinary healthcare team and community outreach partners at a semi-rural health facility in South Africa. The discussion focused on barriers and enablers of access to rehabilitation. Participants identified barriers at various levels, including transport, physical access, financial constraints and poor multi-stakeholder team interaction. The results of the group discussions informed the design of an inclusive model of HIV care. This model was further informed by established integrated rehabilitation models. Participants emphasized that objectives need to respond to policy, improve access to patient-centered care and maintain a multidisciplinary team approach. They proposed that guiding principles should include efficient communication, collaboration of all stakeholders and leadership in teams to enable staff to implement the model. Training of professional staff and lay personnel within task-shifting approaches was seen as an essential enabler to implementation. The health facility as well as outreach services such as intermediate clinics, home-based care, outreach and community-based rehabilitation was identified as important structures for potential rehabilitation interventions.

KEYWORDS: HIV, rehabilitation, model of care, disability, South Africa

Introduction

Rehabilitation professionals in South Africa have seen the effect of people with HIV living longer but facing disabling effects of the virus, other comorbidities and associated side effects of antiretroviral therapy (Nixon et al., 2011). Disability is progressively being viewed by the rehabilitation team through the lens of the World Health Organization's International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF), which is concerned with the participation of an individual factoring in the environment and the psychosocial backdrop framing one's everyday life (Hanass-Hancock, Myezwa, Nixon, & Gibbs, 2014; Myezwa, Stewart, Musenge, & Nesara, 2009). Furthermore, disability may be permanent, temporary or even episodic in an individual living with HIV (Banks, Zuurmond, Ferrand, & Kuper, 2015). Rehabilitation professionals need to approach HIV-related disability within this evolving context to address the dynamic needs of people living with HIV in South Africa.

The rehabilitation framework governing healthcare practice in public South African sectors is under scrutiny as researchers in the field of HIV and disability aim to identify and address the gaps embedded in these systems (Cobbing et al., 2013). South Africa's current National Strategic Plan (NSP) for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) HIV and TB for 2012–2016 incorporate disability. This NSP recognizes people with disabilities as a key population and lists a number of services in relation to access, prevention, treatment, care and support. Although initial efforts are underway to integrate issues related to disability and HIV, more needs to be done to concretely integrate a rehabilitation model to guide delivery of care. Although the plan mentions the prevention of disability in objective three, it does not include any rehabilitation strategies such as physical, vocational and mental health interventions. In order to achieve comprehensive care and a long and healthy life for all South Africans living with the disease, rehabilitation has to be realized as a crucial component of HIV management in reducing disability (Chetty & Hanass-Hancock, 2015; South African National AIDS Council [SANAC], 2011).

Physical and financial accessibility of rehabilitation and sustainability of care influence health outcomes. A recent study in a semi-rural setting in South Africa explored the patients’ perspectives on physiotherapy and revealed barriers to accessing hospital-based services. Patients valued the rehabilitation received but many were not able to maintain treatment. Barriers included financial constraints and physical access of services including transport (Cobbing, Hanass-Hancock, & Deane, 2014). Home-based care has been discussed (Chetty & Hanass-Hancock, 2015; Cobbing et al., 2014; Roos, Myezwa, & van Aswegen, 2015) as a solution to improve accessibility of rehabilitation interventions. Scholars (Chappell & Johannsmeier, 2009; Rule, Lorenzo, & Wolmarans, 2006) argue that community healthcare workers can be skilled to perform certain rehabilitation interventions with patients in their homes. It is thought that such an approach could be informed by decades of experiences with community-based rehabilitation (CBR) as well as experiences within the current task-shifting approach in public health. CBR is an alternative to the traditional central institution-based rehabilitation approach. It includes areas of health, education, livelihood, social participation and empowerment and is delivered through community care workers. Hence, it holds potential to deliver some degree of access to rehabilitation for people living with HIV in resource-poor settings (Finkenflügel, Wolffers, & Huijsman, 2005; Rule et al., 2006). The implementation of the CBR framework can be executed by rehabilitation professionals or trained community rehabilitation facilitators who have been trained to provide care and often also advocate for equality for people with disabilities in general (Chappell & Johannsmeier, 2009). Although these approaches exist and could work in resource-poor settings, there is a lack of integrating these approaches into the response to priority programs such as HIV and AIDS or TB programs. Although research identifies gaps in the current rehabilitation frameworks (Chetty & Hanass-Hancock, 2015; Cobbing et al., 2014), more needs to be done to explore both barriers and facilitators of rehabilitation frameworks in South African settings as well as feasible approaches to offer comprehensive care to address the disabilities related to HIV and its comorbidities.

This study aimed to explore the current rehabilitation service as experienced by people living with HIV and the multidisciplinary healthcare team within a semi-rural setting in South Africa. It forms the first step of an action research study using a learning in action approach which aims to identify the shortfalls of the current model in order to conceptualize a potential model of care in the same community. These preliminary findings will lend itself to the rigorous review of experts in the field of HIV and rehabilitation in the current context in order to achieve a comprehensive model of care.

Methods

Research design

An interpretive qualitative design using Van Manen's pedagogy to obtain depth and insight into the experience of participants accessing the existing framework of rehabilitation of people living with HIV was chosen. This technique provided the researchers with the tools to address the complexity of health services using a participatory approach by means of in-depth discussions with both the researchers and informants participating fully. It allowed researchers to go beyond the data to draw out explanations in phenomena and delve into hidden meaning embedded in words of the research participants (Van Manen, 1984).

Study setting

The study setting as defined in the introduction is semi-rural, meaning that it is away from the city center with limited infrastructure. The area has access to a 200-bed hospital and radial clinics. The hospital provides a service for 750,000 people. It is estimated that more than 250,000 of people living in the catchment area are HIV positive. Due to the dramatic increase in the number of patients suffering from AIDS-related illnesses, the hospital in the area has focused its attention on improving and increasing its capacity to render holistic health care to people living with HIV and their families through various projects. This study is part of such a project and is holistically aimed at developing a model of care to integrate disability and rehabilitation into HIV care at the study setting (Chetty & Hanass-Hancock, 2014; Cobbing et al., 2014).

Participant recruitment and sampling

Thirty participants were purposely recruited using maximum variation to explore various views of stakeholders from a semi-rural healthcare setting in KwaZulu-Natal, South (Patton, 2005). They included the multidisciplinary healthcare team (doctors, physiotherapists, physiotherapy students who rotated through the site for clinical practice, dieticians, social workers, mid-level workers and community healthcare workers); site-affiliated non-governmental organization representative(s) and service users at the study setting. Twenty-one women and nine men participated in the discussion group. Once ethical clearance was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, informed consent was obtained from the participants and relevant authorities. Participation in the focus group was voluntary and no incentives were offered. The biographical data and characteristics of participants are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Biographical data and characteristics of participants (n = 30).

| Characteristic variable number of respondents | |

|---|---|

| Persons living with HIV | 2 |

| Caregivers | 2 |

| Community healthcare workers | 7 |

| Dietician | 1 |

| Doctor | 1 |

| Nurses | 7 |

| Physiotherapists | 3 |

| Physiotherapy students | 4 |

| Physiotherapy assistants | 2 |

| Social worker | 1 |

| Gender | |

| Male | Female |

| 9 | 21 |

| Age of respondents (Years) | |

| 20–29 | 11 |

| 30–39 | 10 |

| 40–49 | 5 |

| 50–59 | 3 |

| Over 60 | 1 |

Data collection

The researchers conducted a focus group discussion adding a participatory paradigm with a guide exploring views of participants on the existing rehabilitation framework (Finch & Lewis, 2003). The researchers developed a focus group guide following the review of relevant literature (Barbour, 2008). The guide prompted views on the existing rehabilitation framework such as barriers to care, stakeholder responsibilities and recommendations on improving service delivery. However, it allowed for flexibility and interaction between researchers and participants on relevant views regarding HIV, disability and rehabilitative care. The discussions were conducted in English, with translations into isiZulu where necessary. Discussions were tape recorded and entered into NVIVO version 9. The researcher also noted nonverbal nuances. The raw data were transcribed verbatim by a research assistant immediately after discussions and disseminated among the key participants for verification. The participants were coded to ensure anonymity.

Data analysis

The researcher has adopted the methodological approach of Van Manen (1984) by turning to the “nature of the lived experience, existential investigation, phenomenological reflection and concluded by phenomenological writing” in analyzing the data. Two researchers coded the narratives after extensive review and debriefing. Data were read, re-read and themes were identified as emerging from the data (Van Manen, 1984). Rigor was achieved by using thick descriptions detailing accounts and settings as described by participants. Furthermore, peer debriefing by an expert in qualitative research served as a platform to discuss emergent themes. Finally, member checking which involved verification of findings by participants was also deemed critical to maintain rigor in this study (Creswell & Miller, 2000).

Results

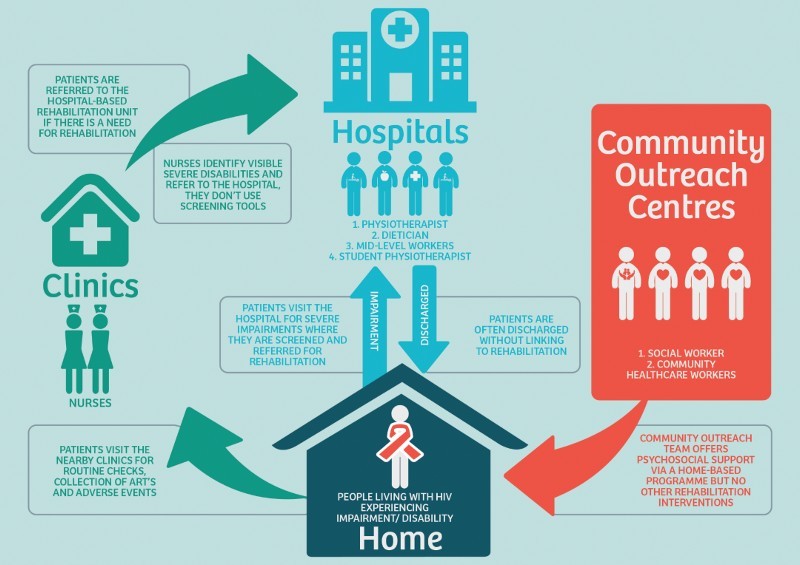

The study participants described the current rehabilitation pathway as in Figure 1 as being centrally situated at the hospital. Patients who needed to access rehabilitation services to address bodily impairments or activity limitations had to visit the hospital or be referred to the hospital from the local clinics. The hospital offered limited services such as physiotherapy and dietetics and lacked major therapeutic disciplines such as occupational therapy and speech therapy.

Figure 1.

Current rehabilitation pathway at study setting.

The analysis of the data revealed several themes with regard to barriers and enablers. Participants identified barriers to rehabilitation such as environmental constrains, fiscal challenges and institutional limitations. Table 2 provides an overview of categories and themes. The results also revealed iterated themes from narratives which were integrated into established existing frameworks of rehabilitation models that use four main categories: objectives, principles, enablers and settings as their foundation (Chetty & Hanass-Hancock, 2015).

Table 2. Summary of categories and themes.

| Categories | Themes |

|---|---|

| Environmental constraints | Centralization of services |

| Commute obstruct | |

| Fiscal challenges | Funding feud |

| Institutional limitations | Staffing vs. workload dilemma |

| Poor collaboration of multidisciplinary team | |

| Participants’ recommendations | Education |

| Proposed model of care |

Environmental constraints

The discussions among participants revealed that in their experience, centralization of services challenges patients’ accessibility to integral care. Commute obstruct posed a further strain on patients, as they experience diverse challenges with regard to transportation to centralized services within hospital settings. Participants explained that patients experienced challenges in regard to time, distance and financial issues. For instance, patients had to travel several times to the clinic and hospitals for rehabilitation or medical care. In addition, some of them experienced difficulty walking longer distances to the clinics or were in need of transportation with a private car which they did not possess

Our patients don't have transport, it is a long hilly walk to the hospital and they are weak. (Community Care worker 5)

Participants felt that rehabilitation should be offered at the local clinics and as home-based care by trained care workers. Participants identified community care workers as more accessible to frail patients and to patients who were unable to access central services. There was vast agreement that the rehabilitation offered at the central hospital was beneficial, but participants believed that community care workers could receive adequate skills training to offer services to patients at nearby clinics and in the form of domiciliary care. The health science students from a local tertiary institution who are placed at the study setting for a clinical practice rotation were also seen as an asset as stakeholders believed that they could be sourced into the community clinics and offer home-based care if needed

If the rehabilitation team can't reach patients then community care workers should be trained properly to do rehab at patients home and at clinics. (Student physiotherapist 3)

Fiscal challenges

It was echoed in the discussions that the financial challenges constraining households in the study setting was a barrier to accessing central services. Participants felt that patients were facing disabling effects of HIV limiting their optimal function and they were unable to resume or obtain employment. They explained further that patients were challenged by being unable to receive therapy to improve function and return to work due to scarcity of money to access these services

Patients are referred from clinic to the hospital for rehabilitation but they have no money to go the hospital, and there is no therapist at the clinic. (Nurse 3)

Participants also explained that in their community, parents of children living with HIV who develop disabilities become caregivers and are unable to work and are faced with the burden of being unable to access health care due to financial constraints. Participants felt that the fiscal challenges facing their community form part of a vicious life cycle

Children with HIV and cerebral palsy need care, vaccines, rehabilitation but can't get to hospital because there is no money. (Physiotherapist 2)

Institutional limitations

A senior staff member at the hospital who participated in the study felt that the lack of staff to offer comprehensive health care affected the rehabilitation of people living with HIV. The rehabilitation team explained that the workload demand was extensive and the high number of patients made it difficult for the limited healthcare staff to offer adequate rehabilitative care. Furthermore, poor collaboration of the multidisciplinary team was a major concern among participants. A physiotherapy assistant verbalized her dissatisfaction of patients being discharged without consultation with the rehabilitation team or follow-up appointments being made. A community care worker felt that when patients were discharged from hospital, they were not reintegrated back into the community and rehabilitation ceased

Staffing-patient ratio is a problem. Large volume of patients and few staff creates a problem for rehabilitation. (Doctor)

Patients are discharged without any discussion with rehabilitation team; there is no follow up at all. (Physiotherapy assistant 1)

Participant's recommendations

The lack of knowledge of caregivers and patients was seen as a hindrance to rehabilitation, as patients were not aware or made aware of the significance of the service. The healthcare team also felt that the ongoing education of all rehabilitation staff was essential to offer optimum care to people living with HIV in their community

Lack of knowledge of patients and caregivers is a big problem. (Nurse 1)

Clinics should have pamphlets for rehabilitation and the physio can come once a month to promote rehabilitation. (Community care worker 2)

The results of the group discussions were used to inform the design of an inclusive framework for a model of HIV rehabilitative care. The framework was informed by established integrated rehabilitation models (Chetty & Hanass-Hancock, 2015). These models focused on four main categories: objectives, principles, enablers and settings. Stakeholders in this study proposed context-specific iterated themes to reflect in these categories as depicted in Figure 2. They emphasized that objectives need to be derived from existing policies, and focus on improved access to patient-centered care using a multidisciplinary team approach. They supposed that efficient communication, collaboration of all stakeholders and leadership in teams need to be the principles on which to build a comprehensive model of care. Education and training for professional healthcare staff and lay personnel within task-shifting approaches were seen as essential enablers. Participants identified the health facility as well as outreach services such as hospital, intermediate clinic, home-based care, outreach and CBR as important settings and structures for timeous intervention.

Figure 2.

Recommended framework informing model of care for rehabilitation.

Discussion

The study explores the existing rehabilitation framework at a semi-rural public healthcare setting in South Africa by engaging in discussions with the multidisciplinary healthcare team; site-affiliated non-governmental organization representative(s) and service users. The experiences of the participants highlighted barriers to rehabilitation and elements of a framework to guide the development of a context-specific model of care for the rehabilitation of people living with HIV.

In a first step, we identified the gaps in the current rehabilitation model at the study setting. Similar to previous work in this setting (Cobbing et al., 2014; Hanass-Hancock & Alli, 2014; van Egeraat, Hanass-Hancock, & Myezwa, 2015), this study identified a lack of accessibility to centrally situated services was a major contributor to barriers of rehabilitation. van Egeraat et al. (2015), in exploring healthcare workers experience of HIV-related disability in the study context, found that healthcare workers felt challenged with the double burden of HIV and disability and often believed that it was beyond their scope to offer rehabilitation. They referred patients to the central hospital, but often did not receive feedback regarding the management. Authors suggested that community healthcare workers needed training and support to deal with the increased incidence of disability related to HIV.

In a subsequent study, Hanass-Hancock and Alli (2014) offered many of the local healthcare workers with training on the intersection of disability and HIV. On evaluating the impact of this training, they found that healthcare workers did make considerable improvement with attitudinal barriers and access to general health care, but they were less successful to change rehabilitation practice (Hanass-Hancock & Alli, 2014).

Further evidence from the current study indicated fiscal challenges on both the service delivery side and the affordability of services. On the one hand, the funding feud delves into the vicious cycle between poverty, disability and rehabilitation. People living with HIV experiencing disabilities in this study were faced with financial constraints limiting them from attending the hospital-based rehabilitation sessions. Furthermore, they report being unable to return to work to obtain an income to supplement the cost of these visits. The cycle of not achieving optimal function through rehabilitation to return to work as a result of not having the financial means to access hospital-based rehabilitation sessions has been echoed by Cobbing et al. (2014) where patients benefited from the rehabilitation they received, but barriers such as lack of transport to get to their nearest hospital and lack of money to pay for transport prevented continuity of care. On the other hand, the lack of rehabilitation staff and allocation of resources to the rehabilitation system provided barriers to counteract this viscous cycle.

Participants in this study also identified structural challenges limiting rehabilitation such as poor multidisciplinary collaboration and lack of identification and referral as a barrier to rehabilitation. Similar observations were made by Chetty and Maharaj (2013) investigating the collaboration of healthcare workers concurred, indicting a lack of staff and collaboration as challenges to rehabilitation of people living with HIV. The lack of professional healthcare staff within the public healthcare domain has been of great concern in South African healthcare contexts (Cobbing et al., 2013; Mayosi & Benatar, 2014). Mayosi and Benatar (2014) report the migration of healthcare professionals to well-resourced countries such as Australia, Canada and the UK leaving South Africa under greater financial and workforce strain. The shortage of rehabilitation staff in the region is even more daunting, especially in resource-poor settings despite the large population of people in need of the service (Cobbing et al., 2013). CBR offers one avenue to compensate for staff shortages in resource-poor settings. Community members, family of people living with HIV and people living with HIV themselves can be capacitated through task shifting and training to provide some form of rehabilitation within communities and homes (Chappell & Johannsmeier, 2009). The empowering and skill development of community care workers and caregivers could be harnessed to address issues of accessibility. In the current study setting, people living with HIV needing rehabilitation have to access services at the centrally situated hospital. There are no rehabilitation services provided at the radial clinics. However, the community outreach center, which is a site-affiliated non-governmental organization, sends community healthcare workers into the community and into patient's homes to offer psychosocial support. Participants felt that the current model could be utilized through enabling these outreach services to provide CBR and home-based care approaches.

CBR has, however, not been sufficiently assessed with regard to its effectiveness within a South African rehabilitation healthcare setting. A study by Chappell and Johannsmeier (2009) on the impact of CBR implemented by community rehabilitation facilitators explored the broadened scope of the role of a mid-level worker in providing more than individual medical rehabilitation but also encompassed the advocacy for equalization of opportunities and community development. Potterton, Stewart, Cooper, and Becker (2010) have documented how caregivers can be enabled to perform home stimulation programs initiating significant improvement in the cognitive and motor development of children infected with HIV (Potterton et al., 2010). Some studies report on health workers being able to overcome structural challenges. For instance, Rule et al. (2006) highlight how a community rehabilitation facilitator overcame the challenge of transport constraints in the public sector by advocating that taxi owners and drivers should create opportunity for people with disabilities to access their vehicles reporting improvement in accessing health services at the end of the case.

In a second step, we used the information of the participants to inform a framework that supports the development of an appropriate model of care. For this purpose, an integrated framework using a synthesis of Australian rehabilitation models was used as the lens to interpret participants’ recommendations for the framework of care (Chetty & Hanass-Hancock, 2015).

The four main categories, that is, objectives, principles, enablers and settings, are discussed congruently. Similar to this study, the synthesized framework depicted the improvement of access to care, reducing inequality in health status, providing safe, high-quality health care, promoting a patient-centered continuum of care and optimizing health services as being part of the objectives. Leadership and a multidisciplinary team approach were common principles in the frameworks; however, evidence-based practice as a guiding principle lacked attention by participants in this study. Education and training for rehabilitation service providers at all points of care were a common enabler in both frameworks, but task shifting to empower lay personnel such as community healthcare workers was seen as a key imperative in this study. Stakeholders involved in this study did not highlight the need for data management systems to manage patient information, which was a dominant necessity in the summary of the rehabilitation models used as the framework for the discussions. The specific setting, however, was commonly viewed as essential in providing appropriate timeous intervention within the delivery care system (Chetty & Hanass-Hancock, 2015).

Conclusion

South Africa's NSP for STIs HIV and TB for 2012–2016 including disability in its design is a positive paradigm shift in health care for the country (SANAC, 2011). Although rehabilitation is an identifiable missing component, South Africa is currently reviewing its rehabilitation frameworks. Although the study is limited to a single semi-rural healthcare setting, it offers pertinent evidence of gaps in the current rehabilitation framework and identifies key recommendations to facilitate the development of a comprehensive model of care for people living with HIV. However, further investigation is needed in collaboration with a wider audience such as experts within the field of HIV and rehabilitation within the South African context to adapt and validate the model prior to the piloting phase within the study setting.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council [National Health Scholarship Award].

ORCID

Verusia Chetty http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2934-8687

Jill Hanass-Hancock http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3662-8548

References

- Banks L. M., Zuurmond M., Ferrand R., Kuper H. The relationship between HIV and prevalence of disabilities in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review (FA) Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2015;(4):411–429. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour R. Doing focus groups. London: Sage; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell P., Johannsmeier C. The impact of community based rehabilitation as implemented by community rehabilitation facilitators on people with disabilities, their families and communities within South Africa. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2009;(1):7–13. doi: 10.1080/09638280802280429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty V., Hanass-Hancock J. Development of a model of care for rehabilitation of people living with HIV in a semirural setting in South Africa. JMIR research protocols. 2014;(4) doi: 10.2196/resprot.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty V., Hanass-Hancock J. The need for a rehabilitation model to address the disparities of public healthcare for people living with HIV in South Africa. African Journal of Disability. 2015;(1):1–6. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v4i1.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chetty V., Maharaj S. S. Collaboration between health professionals in the era of antiretroviral therapy. Journal of the Association of Nurses in Aids Care. 2013;(2):166–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbing S., Chetty V., Hanass-Hancock J., Jelsma J., Myezwa H., Nixon S. Position paper: The essential role of physiotherapists in providing rehabilitation services to people living with HIV in South Africa. SA Journal of Physiotherapy. 2013;(1):22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbing S., Hanass-Hancock J., Deane M. Physiotherapy rehabilitation in the context of HIV and disability in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2014;(20):1687–1694. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.872199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., Miller D. L. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice. 2000;(3):124–130. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Egeraat L., Hanass-Hancock J., Myezwa H. HIV-related disabilities: An extra burden to HIV and AIDS healthcare workers? African Journal of AIDS Research. 2015;(3):285–294. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2015.1084938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch H., Lewis J. 2003 Focus groups. In J. Ritchie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 170–198). London: Sage.

- Finkenflügel H., Wolffers I., Huijsman R. The evidence base for community-based rehabilitation: A literature review. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. 2005;(3):187–201. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200509000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanass-Hancock J., Alli F. Closing the gap: Training for healthcare workers and people with disabilities on the interrelationship of HIV and disability. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2014;(21):2012–2021. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.991455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanass-Hancock J., Myezwa H., Nixon S. A., Gibbs A. “When I was no longer able to see and walk, that is when I was affected most”: Experiences of disability in people living with HIV in South Africa. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2014;37(22):2051–2060. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.993432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayosi B. M., Benatar S. R. Health and health care in South Africa – 20 years after Mandela. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;(14):1344–1353. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1405012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myezwa H., Stewart A., Musenge E., Nesara P. Assessment of HIV-positive in-patients using the international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) at Chris Hani Baragwanath hospital, Johannesburg. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2009;(1):93–105. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.1.10.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon S., Forman L., Hanass-Hancock J., Mac-Seing M., Munyanukato N., Myezwa H., Retis C. Rehabilitation: A crucial component in the future of HIV care and support: Opinion. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine. 2011;(2):12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. Qualitative research. John Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Potterton J., Stewart A., Cooper P., Becker P. The effect of a basic home stimulation programme on the development of young children infected with HIV. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2010;(6):547–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos R., Myezwa H., van Aswegen H. “Not easy at all but I am trying”: Barriers and facilitators to physical activity in a South African cohort of people living with HIV participating in a home-based pedometer walking programme. AIDS Care. 2015;(2):235–239. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.951309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rule S., Lorenzo T., Wolmarans M., Watermeyer B., Swartz L., Lorenzo T., Priestley M. Community-based rehabilitation: New challenges. Disability and Social Change: A South African Agenda. 2006:273–290. [Google Scholar]

- South African National AIDS Council. National Strategic Plan on HIV STIs and TB. 2012–2016. Summary. Johannesburg: SANAC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen M. “Doing” phenomenological research and writing: An introduction. Alberta, Canada: University of Alberta; 1984. [Google Scholar]