ABSTRACT

Some previous studies have revealed a negative impact of enacted stigma on post-traumatic growth (PTG) of children affected by HIV/AIDS, but little is known about protective psychological factors that can mitigate the effect of enacted stigma on children's PTG. This study aims to examine the mediating effects of perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulation on the relationship between enacted stigma and PTG among HIV-affected children. Cross-sectional data were collected from 790 children affected by parental HIV (382 girls, 408 boys) aged 6–17 years in 2012 in rural central China. Multiple regression was conducted to test the mediation model. The study found that the experience of enacted stigma had a negative effect on PTG among children affected by HIV/AIDS. Emotional regulation together with hopefulness and perceived social support mediated the impact of enacted stigma on PTG. Perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulation offer multiple levels of protection that can mitigate the impact of enacted stigma on PTG. Results suggest that future psychological intervention programs should seek strategies to reduce the stigmatizing experience of these children and promote children's level of PTG, and health professionals should also emphasize the development of these protective psychological factors.

KEYWORDS: Enacted stigma, perceived social support, hopefulness, emotional regulation, post-traumatic growth, children affected by HIV/AIDS, China

Introduction

According to Kilmer et al. (2009), the term post-traumatic growth (PTG) refers to a positive change resulting from the struggle with traumatic events. People under the pressure of the traumatic events (e.g. being HIV-affected) are more likely to develop a positive perspective and change in a wake of traumatic events, thereby, PTG occurs (Kleim & Ehlers, 2009; Sawyer & Ayers, 2009; Sheikh, 2008). PTG has been considered that individuals have the capacity to develop a positive perception and further undergo positive psychological changes in the wake of adverse experience (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). However, HIV-affected children frequently experience loss of acceptance and support due to suffering from stigmatization. They may tend to have a negative attitude toward their future development. Although some studies have investigated the relationship between stigmatization and various psychological symptoms among children affected by parental HIV, research aimed at exploring the relationship between stigmatization and children's PTG as well as potential protective factors is limited. Given the gap in the literature, this study uses baseline data from a large resilience-based intervention for children affected by HIV/AIDS in China to identify potential protective factors, such as perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulation, which can enhance children's PTG in the context of parental HIV/AIDS. Moreover, the mechanism by which stigmatization affects the PTG of children affected by parental HIV/AIDS is examined.

Enacted stigma is one form of the HIV-related stigma which refers to acts of discrimination and humiliation directly against person living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) because of their stigmatized status (Chi, Li, Zhao, & Zhao, 2013). For past two decades, the HIV-related stigma has been an important issue in the field of HIV prevention and intervention (Deacon, Stephney, & Prosalendis, 2005). HIV-related stigma has been shown to have an adverse impact on an individual's mental health, and may be linked to depression, anxiety, fear, and stress (Li, Lee, Thammawijaya, Jiraphongsa, & Rotheram-Borus, 2009; Piot, 2001; Van Brakel, 2006). Moreover, HIV-related stigma may also negatively affect various aspects of PLWHA and their non-infected children such as openness to HIV test-seeking, willingness to disclose HIV status, health-seeking behaviors, quality of health care, and social support solicited and received (Boyd, Simpson, Hart, Johnstone, & Goldberg, 1999; Muyinda, Seeley, Pickering, & Barton 1997; Sowell et al., 1997). Foster, Makufa, Drew, Mashumba, and Kambeu (1997) reported that children affected by HIV in rural Zimbabwe experienced anxiety, fear, stigmatization, depression, and stress. Experiencing stigma was associated with poorer psychosocial adjustment and greater problem behavior among HIV-affected children (Forehand et al., 1998). In particular, enacted stigma (i.e. overt behaviors) is primarily manifested as interpersonal discrimination, and is associated with severe physical and psychological problems among HIV-affected children (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983; Link & Phelan, 2006; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). Because children are less likely to control their situation than adults, they may not know their rights or may lack the ability to defend their rights (Deacon et al., 2005). As parents living with HIV suffer from the negative effects of enacted stigma, children's psychological grief may be exacerbated, and their access to education and healthcare may decrease (Deacon et al., 2005). Although the negative impact of HIV-related stigma has been well documented in a large number of studies, it is still equally important to examine the concept of resilience and identify those HIV-affected children who have experienced enacted stigma and yet display PTG. A better understanding of the impact of enacted stigma on PTG can inform researchers about how to develop interventions that may make PTG more likely for HIV-affected children.

A likely mediator of the association between enacted stigma and PTG in HIV-affected children is perceived social support. Perceived social support represents the subjective perceptions of the extent to which people are available to provide social resource and assistance (Cohen & McKay, 1984). Perceived social support is a potential protective factor that it may allow people to deal more effectively with traumatic events because they may sense that others will be there to assist them if necessary (Xanthopoulos & Daniel, 2013). In recent years, many studies have provided evidence to support the positive effect of perceived social support in coping with traumatic events including discrimination (Galvan, Davis, Banks, & Bing, 2008; Linley & Joseph, 2004; Prati & Pietrantoni, 2009). Further, many investigators have shown that perceived social support is strongly related to positive outcomes for vulnerable children (Forman, 1988; VanTassel-Baska, Olszewski-Kubilius, & Kulieke, 1994). Lack of social support may lead to children's vulnerability to develop cognitive, emotional, and behavioral difficulties, as well as reduce the level of PTG (Brooks, 1994; Compas, Slavin, Wagner, & Vannatta, 1986). Therefore, it is meaningful to explore whether perceived social support mediates the association between experiences of enacted stigma and PTG among children affected by parental HIV/AIDS.

Similarly, hopefulness may mediate the association between enacted stigma and PTG. Hopefulness is defined as the extent to which people possess a positive and reality-based faith of a positive future for themselves (Hinds, 1988; Hinds & Gattuso, 1991). If people who have more hopefulness for their future, they may be able to cope better with the negative outcomes of traumatic events (Smith, 1983). Early research has demonstrated that hopefulness is a protective factor that may positively impact a person's psychosocial development, including perceived level of self-esteem, resilience, effective coping, and personal growth (Dubree & Vogelpohl, 1980; Schneider, 1980). One study has further found that hopefulness is positively linked to people's PTG (Joseph, Murphy, & Regel, 2012). Furthermore, an additional study has documented that hopefulness is associated with positive adaptation to stress (Ong , Bergeman, Bisconti, & Wallace, 2006). However, research regarding the association between hopefulness and PTG among HIV-affected children is scarce. It is unclear whether hopefulness can act as a mediator and enable children to improve PTG following traumatic events associated with parental HIV/AIDS.

Emotional regulation has also been identified as a possible psychological buffer against adversity (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1997; Paivio & Laurent, 2001). Since emotional regulation encompasses the extrinsic and intrinsic processes for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions in order to achieve goals, effective emotional regulation enables individuals to express their emotions appropriately and, thereby, receive more support from others (Thompson, 1994). One empirical study conducted with myocardial infarction patients reported that a large part of the variance (24%) of PTG was explained by emotional regulation (Garnefski, Kraaij, Schroevers, & Somsen, 2008). Emotional regulation is a primary developmental task in early childhood (Calkins & Hill, 2007). Nevertheless, relatively few studies have tested the link between emotional regulation and PTG among HIV-affected children, and examined whether emotional regulation may serve as a mediator to reduce the negative effects of enacted stigma for these children'.

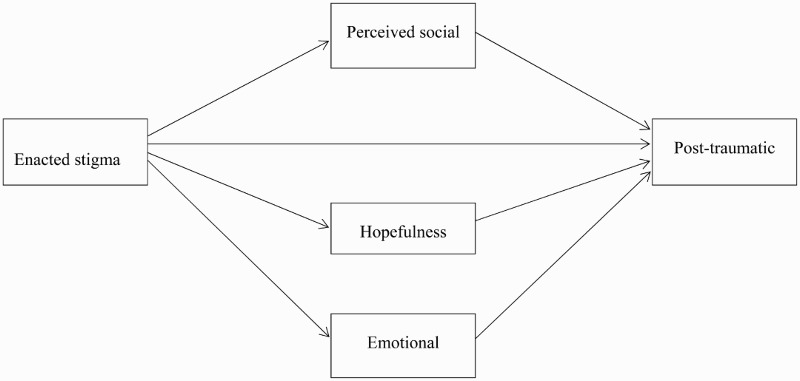

The current study investigated the association between enacted stigma and PTG in a large sample of children aged 6–18 years and affected by parental HIV/AIDS in rural China. The primary goal was to examine whether the effect of enacted stigma on PTG would be mediated by perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulation among those children. We hypothesized that (1) PTG would be negatively associated with enacted stigma and (2) perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulation would mediate the relationship between enacted stigma and PTG. The hypothesized model of associations among enacted stigma, perceived social support, hopefulness, emotional regulation, and PTG is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model.

Method

Participants

The current study used baseline data from a randomized controlled trial study. We collected data from a sample of 790 HIV-affected children ages 6–17 years in rural China, where many residents have been infected with HIV through unhygienic blood collection.

Procedure

Data were collected in 2012, and the children were recruited from the village and the local school system from a rural county in central China. The Institutional Review Boards at Wayne State University in the United States and Henan University in China approved the study protocol. We accessed village-level HIV surveillance data from the county's anti-epidemic station to identify villages with the highest numbers of HIV-infected individuals and/or HIV-related deaths in the area. We worked with the local village leaders to generate lists of families caring for orphans or with a confirmed diagnosis of parental HIV/AIDS. We approached the families on the lists and recruited one child from each family to participate in the study. Appropriate informed consent was obtained from the children and their caregivers prior to their participation.

All participants responded to a questionnaire including measures on enacted stigma, perceived social support, hopefulness, emotional regulation, and PTG. Most of the surveys were self-administrated in a small group in the presence of two interviewers. For a few children who had reading difficulties, the interviewers read the survey items and recorded their responses in a private room.

Measures

Enacted stigma. Enacted stigma was measured with a 14-item scale, in which children were asked to report whether they had experienced stigmatized actions after a parental HIV infection in the past 6 months. Sample items included “being called bad names”, “being teased or picked on by other kids”, and “relatives stopped visiting when parents got sick or died”. The items are rated on a 5-point response (1 = “never happened” to 5 = “always happened”). The Cronbach alpha was .80 in the current study.

Post-traumatic growth. PTG was measured using the PTG scale for children (PTGI-CR), which was developed by Kilmer et al. (2009) and was subsequently adapted to the Chinese population by Yu et al. (2010). PTGI-CR includes eight items to evaluate children's positive experience in the aftermath of trauma (e.g. “Do something that I was unable to do before”). The items are rated on a 4-point response (range from 0 = never to 3 = often). The Cronbach alpha for this scale was .77 in the current study.

Hopefulness. Participants reported their expectations and hopefulness about their future using the Hopefulness about Future scale (Hope). This scale was developed by Whitaker, Miller, and Clark (2000) and was used among Chinese children affected by HIV/AIDS (Li et al., 2009). Hope includes four items such as “I will live in a good place” and “I will get a good job”. Each item has a 4-point Likert response ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The Cronbach alpha for this scale was .73 in the current study.

Perceived social support (PSS). PSS among children was measured by a 16-item scale (Hong et al., 2010) which was modified from Zimet's multidimensional scale of PSS (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1998). The modified version measures PSS from four sources: family, friends, teachers, and significant others. The sample items include “I can count on my friends when things go wrong”, “my teachers really try to help me”, and “I have a special person who is a real source of comfort to me”. The answers were scored on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). In the current study, the Cronbach alpha for this scale was .87.

Emotional regulation. Participants completed a 6-item scale, which is a subscale of The Social Competence Scale developed by Corrigan (2002). The emotional Regulation Scale is utilized to evaluate participants’ competence of emotional adjustment (e.g. “I can control temper when I have a disagreement with my friends”). The items are rated on a 5-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very well). The Cronbach alpha for this scale was .80 in the current study.

A mean score was calculated for items belonging to each scale with a higher score indicating a higher level of enacted stigma, PTG, perceived social support, emotional regulation, and hopefulness.

Statistical analysis

The Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to identify significant associations among all study variables. We performed multiple regression analysis to test indirect effects of three mediators: perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulation. Recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986), first regression tested the relationship between enacted stigma and PTG. The second regression evaluated whether there was a significant association between enacted stigma and each of the three mediators. The final regression determined whether the effect of enacted stigma was reduced when each of the three mediators was introduced into the model predicting PTG. All the data analyses were conducted using SPSS 21.

Results

Characteristics of HIV-affected children

Table 1 outlines characteristics of HIV-affected children. The mean age of the 790 children (382 girls, 408 boys) who participated in the study was 10.51 years (SD = 1.99), with a range between 6 and 17 years. Approximately 97% of the sample of participating children were of Han ethnicity.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, Cronbach's alpha, and correlations (N = 790).

| Variable | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Cronbach's alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Enacted stigma | 1.78 (0.76) | – | .80 | ||||

| 2. Post-traumatic growth | 2.77 (0.61) | −.12** | – | .77 | |||

| 3. Perceived social support | 2.73 (0.56) | −.07* | .27** | – | .87 | ||

| 4. Hopefulness | 2.82 (0.68) | −.14** | .27** | .34** | – | .73 | |

| 5. Emotional regulation | 2.73 (0.56) | −.18** | .36** | .36** | .33** | – | − .80 |

| 6. Age | 10.51 (1.98) | −.17** | .002 | .02 | .11** | .05 |

* p < .05.

** p < .01

Preliminary analyses: correlations

The correlations, means, and SD of all variables are presented in Table 1. The results showed that children who experienced more enacted stigma reported lower PTG (r = −.12, p < .01), less perceived social support (r = −.07, p < .05), less hopefulness (r = −.14, p < .01), and poorer emotional regulation (r = −.18, p < .01). Moreover, children who exhibited greater PTG also reported more perceived social support (r = .27, p < .01), hopefulness (r = .27, p < .01), and better emotional regulation (r = .36, p < .01).

Mediation effects

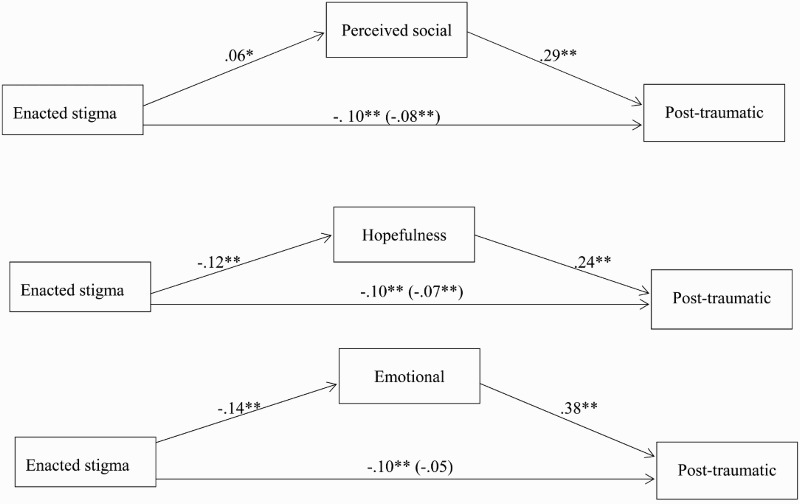

Multiple linear regressions showed the result as follows: that PTG was negatively associated with enacted stigma [β = −.10, p < .01]; perceived social support was negatively associated with enacted stigma [β = −.06, p < .05]; hopefulness was negatively associated with enacted stigma [β = −.12, p < .01]; and emotional regulation was negatively related to enacted stigma [β = −.14, p < .01]. Further, multiple regression analysis showed statistically significant indirect effects of enacted stigma on PTG through each of three mediator variables (Table 2 and Figure 2): perceived social support [indirect effect = −.02, 95%CI, (−0.03, −0.008)], hopefulness [indirect effect = −.03, 95%CI (−0.05, −0.01)], and emotional regulation [indirect effect = −.05, 95%CI (−0.08, −0.02)].

Table 2. Summary of indirect effects and confidence intervals of three mediators (N = 790).

| Mediators | Indirect effects | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived social support | − 0.02** | 0.01 | − 0.03 | − 0.01 |

| 2. Hopefulness | −0.03** | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

| 3. Emotional regulation | −0.05** | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.02 |

* p < .05.

** p < .01.

Figure 2.

Final path model showing the indirect effect of enacted stigma on PTG via PSS, hopefulness, and emotional regulation.

Discussion

In the current study, we tested three potential resilience factors that acted as mediators in associations between enacted stigma and PTG among a sample of children affected by parental HIV in rural China. Statistical analyses yielded overall support for the model and were consistent with the hypotheses.

The current study provided preliminary evidence that enacted stigma is negatively associated with PTG among HIV-affected children in rural China. As predicted by the hypothesis, PTG was found to be negatively associated with enacted stigma. Our results indicated that although PTG may occur as a result of dealing with traumatic events (Kleim & Ehlers, 2009; Sawyer & Ayers, 2009; Sheikh, 2008), this experience is not universal. The results underscore the need for effective interventions to reduce the negative effect of enacted stigma and to identify potential protective factors in improving the PTG of HIV-affected children.

Further, the mediation effects of perceived social support, hopefulness, and emotional regulation have been found by our study. The findings shed new light on the need for intervention studies and the role that these constructs play as a significant buffer to reduce the negative effects of enacted stigma on children's PTG. For perceived social support, the result is consistent with previous studies (Brooks, 1994; Prati & Pietrantoni, 2009; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004) which demonstrated that children with more perceived social support may have less enacted stigma and experiencing greater PTG. Since social isolation and stigmatization may block the path of those children searching for support, interventions directed at enhancing perceived social support would be beneficial for reducing the effect of enacted stigma in HIV-affected children. Simultaneously, we found that hopefulness mediated the effect of enacted stigma on children's PTG in rural China. Our findings support and extend the previous studies indicating that hopefulness is an important protective factor linked with children and adolescent PTG (Cantrell & Lupinacci, 2004; Creamer et al., 2009). Further, our study may bring a new perspective that hopefulness, as a potential resilience factor, can help HIV-affected children to bounce back from traumatic events and be a springboard to further thriving and positive personal growth. Finally, while emotional regulation has been previously identified as a predictor of PTG for patients with myocardial infarction, our findings suggest that emotional regulation can reduce the negative effect of enacted stigma on PTG among HIV-affected children in rural China (Garnefski et al., 2008). Moreover, the current study suggests that the interventions should pay closer attention to efficient emotional strategies – enhancing and training of the capacity of emotional regulation among HIV-affected children.

Limitations and conclusions

Some limitations should be noted. First, the baseline data used in the current study were based on observed relationships and thus should be viewed with caution. Second, the sample of this study may not be representative of all children affected by HIV/AIDS in other settings (i.e. central China) because the HIV epidemic in the research site included was primarily due to unhygienic blood collection. Third, the wide age range of children is a limitation in the current study and thus may not be sensitive to changes that occur at varying developmental stages.

Despite these limitations, the current study is one of the first efforts to provide empirical evidence that three specific potential resilience factors can effectively reduce the adverse effect of enacted stigma on children's PTG in rural China. Based upon our findings, interventions with HIV-affected children could benefit from identification of various coping strategies in the face of traumatic events. These may include psychological and social efforts to reduce the impact of enacted stigma such as support seeking, hope and belief building, as well as training in emotional regulation capacity. Future interventions should not only focus on the elimination or reduction of negative symptoms, such as depression and stress, but also on the promotion of potential resilience factors and a general increase in children's PTG. The findings in the current study also suggest that interventions should focus on exploring the resilience factors from different domains, because increasing resilience factors may facilitate a better level of children's PTG. Our finding contributes to enhance comprehensive knowledge base on potential resilience factors associated with HIV stigma and PTG among HIV-affected children. This knowledge can inform interventions designed to mitigate adverse effects of HIV stigma, as well as improve the children's PTG.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Sayward Harrison, PhD, and Joanne Zwemer for help in preparing the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study reported in this article was supported by NIH Research Grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR13466).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Baron R. M., Kenny D. A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd F. M., Simpson W. M., Hart G. J., Johnstone F. D., Goldberg D. J. What do pregnant women think about the HIV test? A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 1999;(1):21–29. doi: 10.1080/09540129948171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks R. Children at risk: Fostering resilience and hope. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1994;(4):545–553. doi: 10.1037/h0079565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins S. D., Hills A. Caregiver influences on emerging emotion regulation: Biological and environmental transactions in early development. In: Gross J. J., editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell M. A., Lupinacci P. A predictive model of hopefulness for adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;(6):478–485. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(04)00088-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi P., Li X., Zhao J., Zhao G. Vicious circle of perceived stigma, enacted stigma and depressive symptoms among children affected by HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;(6):1054–1062. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0649-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D., Rogosch F. A. The role of self-organization in the promotion of resilience in maltreated children. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;(4):799–817. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Kamarck T., Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., McKay G. Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. Handbook of Psychology and Health. 1984:253–267. [Google Scholar]

- Compas B., Slavin L., Wagner B., Vannatta K. Relationship of life events and social support with psychological dysfunction among adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1986;(3):205–221. doi: 10.1007/BF02139123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan A. 2002 Social Competence Scale – Parent Version: Grade 1/year 2 (Fast Track Project Technical Report). Retrieved October, 12, 2007.

- Creamer M., O'Donnell M. L., Carboon I., Lewis V., Densley K., McFarlane A., Bryant R. A. Evaluation of the dispositional hope scale in injury survivors. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;(4):613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon H., Stephney I., Prosalendis S. Understanding HIV/AIDS stigma: A theoretical and methodological analysis. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dubree M., Vogelpohl R. When hope dies-so night the patient. AJN the American Journal of Nursing. 1980;(11):2046–2049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R., Steele R., Armistead L., Morse E., Simon P., Clark L. The family health project: Psychosocial adjustment of children whose mothers are HIV infected. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;(3):513–520. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman E. A. The effects of social support and school placement on the self – concept of LD students. Learning Disability Quarterly. 1988;(2):115–124. doi: 10.2307/1510989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster G., Makufa C., Drew R., Mashumba S., Kambeu S. Perceptions of children and community members concerning the circumstances of orphans in rural Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 1997;(4):391–405. doi: 10.1080/713613166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan F. H., Davis E. M., Banks D., Bing E. G. HIV stigma and social support among African Americans. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2008;(5):423–436. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N., Kraaij V., Schroevers M. J., Somsen G. A. Post-traumatic growth after a myocardial infarction: A matter of personality, psychological health, or cognitive coping? Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2008;(4):270–277. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds P. S. Adolescent hopefulness in illness and health. Advances in Nursing Science. 1988;(3):79–88. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198804000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds P. S., Gattuso J. S. Measuring hopefulness in adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 1991;(2):92–94. doi: 10.1177/104345429100800241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y., Li X., Fang X., Zhao G., Lin X., Zhang J., Zhang L. Perceived social support and psychosocial distress among children affected by AIDS in China. Community Mental Health Journal. 2010;(1):33–43. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9201-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S., Murphy D., Regel S. An affective–cognitive processing model of post-traumatic growth. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2012;(4):316–325. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer R. P., Gil-Rivas V., Tedeschi R. G., Cann A., Calhoun L. G., Buchanan T., Taku K. Use of the revised posttraumatic growth inventory for children. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;(3):248–253. doi: 10.1002/jts.20410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim B., Ehlers A. Evidence for a curvilinear relationship between posttraumatic growth and post-trauma depression and PTSD in assault survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009;(1):45–52. doi: 10.1002/jts.20378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Lee S. J., Thammawijaya P., Jiraphongsa C., Rotheram-Borus M. J. Stigma, social support, and depression among people living with HIV in Thailand. AIDS Care. 2009;(8):1007–1013. doi: 10.1080/09540120802614358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Barnett D., Fang X., Lin X., Zhao G., Zhao J., Stanton B. Lifetime incidences of traumatic events and mental health among children affected by HIV/AIDS in rural China. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;(5):731–744. doi: 10.1080/15374410903103601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B. G., Phelan J. C. Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet. 2006;(9509):528–529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linley P. A., Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;(1):11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyinda H., Seeley J., Pickering H., Barton T. Social aspects of AIDS-related stigma in rural Uganda. Health & Place. 1997;(3):143–147. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8292(97)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong A. D., Bergeman C. S., Bisconti T. L., Wallace K. A. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;(4):730–749. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paivio S. C., Laurent C. Empathy and emotion regulation: Reprocessing memories of childhood abuse. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;(2):213–226. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:2<213::AID-JCLP7>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe E. A., Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piot P. Stigma, bias present barriers in fight against AIDS pandemic. AIDS Policy & Law. 2001;(18):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G., Pietrantoni L. Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2009;(5):364–388. doi: 10.1080/15325020902724271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer A., Ayers S. Post-traumatic growth in women after childbirth. Psychology and Health. 2009;(4):457–471. doi: 10.1080/08870440701864520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J. S. Hopelessness and helplessness. Journal of Psychiatric Nursing and Mental Health Services. 1980;(3):12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh A. I. Posttraumatic growth in trauma survivors: Implications for practice. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2008;(1):85–97. doi: 10.1080/09515070801896186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. B. Hope and despair: Keys to the socio-psychodynamics of youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1983;(3):388–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1983.tb03382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell R. L., Lowenstein A., Moneyham L., Demi A., Mizuno Y., Seals B. F. Resources, stigma, and patterns of disclosure in rural women with HIV infection. Public Health Nursing. 1997;(5):302–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1997.tb00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi R. G., Calhoun L. G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;(1):1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. A. Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;(2–3):25–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brakel W. H. Measuring health-related stigma – a literature review. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2006;(3):307–334. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanTassel-Baska J., Olszewski-Kubilius P., Kulieke M. A study of self-concept and social support in advantaged and disadvantaged seventh and eighth grade gifted students. Roeper Review. 1994;(3):186–191. doi: 10.1080/02783199409553570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker D. J., Miller K. S., Clark L. F. Reconceptualizing adolescent sexual behavior: Beyond did they or didn't they? Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;(3):111–117. doi: 10.2307/2648159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulos M. S., Daniel L. C. Coping and social support. In: Nezu A. M., Nezu C. M., Geller P. A., Weiner I. B., Nezu A. M., Nezu C. M., Weiner I. B., editors. Handbook of psychology, Vol. 9: Health psychology. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yu X. N., Lau J. T., Zhang J., Mak W. W., Choi K. C., Lui W. W., Chan E. Y. Posttraumatic growth and reduced suicidal ideation among adolescents at month 1 after the Sichuan Earthquake. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;(1):327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G. D., Dahlem N. W., Zimet S. G., Farley G. K. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;(1):30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]