Abstract

Youth and young adults (19–24 years of age) shoulder the burden of sexually transmitted infections accounting for nearly half of all new infections annually. Mobile technology is one way that we have reached this population with safer sex information but challenges exist with the delivery process. The literature between 2010 and 2015 was reviewed for data on safe sex and sexual health information delivered using mobile cell phone devices. A search for relevant databases revealed that 17 articles met our inclusion criteria. Findings suggest that mobile cell phone interventions are an effective mode for delivering safe sex and sexual health information to youth; those at the highest risk may not be able to access cell phones based on availability and cost of the text messages or data plans.

Keywords: mobile, safe sex, sexual health, practices, recommendations

Video abstract

Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 19.7 million sexually transmitted infections (STIs) occur each year.1 While preventable, these infections are a major health concern because of the probability that those infected will be reinfected with the same STI or a new one. Youth and young adults (19–24 years of age) account for nearly half of the new infections,1 primarily as a result of risky sexual behaviors. Among high school students surveyed in the 2013 Youth Behavior Surveillance Survey,2 47% reported having had sexual intercourse, 34% had had sexual intercourse during the previous 3 months, and of these 41% did not use a condom the last time they had sex. Additionally, 15% of the youth had had sex with four or more people during their life, and only 22% reported having ever been tested for HIV.

Mobile technology has become a popular option for delivering safer sex interventions for adolescents. According to a Pew Research Center survey, 78% of teens now have a cell phone and almost half (47%) own Smartphones.3 One in four teens (23%) has a tablet computer, and 93% have a computer or have access to one at home. In addition, seven in ten (71%) have access to a laptop or desktop that is shared with family members, making access to social media sites and text messaging a safer sex health promotion option. However, despite the increased use of mobile technology, it remains unclear how effective safer sex education is in reducing sexual risk behaviors. Accordingly, we conducted a review of the literature to examine current practices and recommendations for future use of mobile technology for promoting sexual health and reducing the risk of STIs among youth.

Methods

Studies were included in the review if they: 1) were original reports; 2) pertained to sexual health; 3) used a quantitative or qualitative research design; 4) involved adolescents or had the word adolescent in the title; 5) were published in a peer reviewed journal; and 6) were conducted within the past 5 years. Studies were excluded if published in languages other than English. Based on the National Institutes of Health definition of a child4 and the World Health Organization definition of adolescence, we set the upper age limit of 20 years and the lower age limit of 12 years for adolescence.5 We defined safe sex as the ability to prevent oneself and a sexual partner from contracting an STI or becoming pregnant by using protective devices, such as condoms or dental dams.

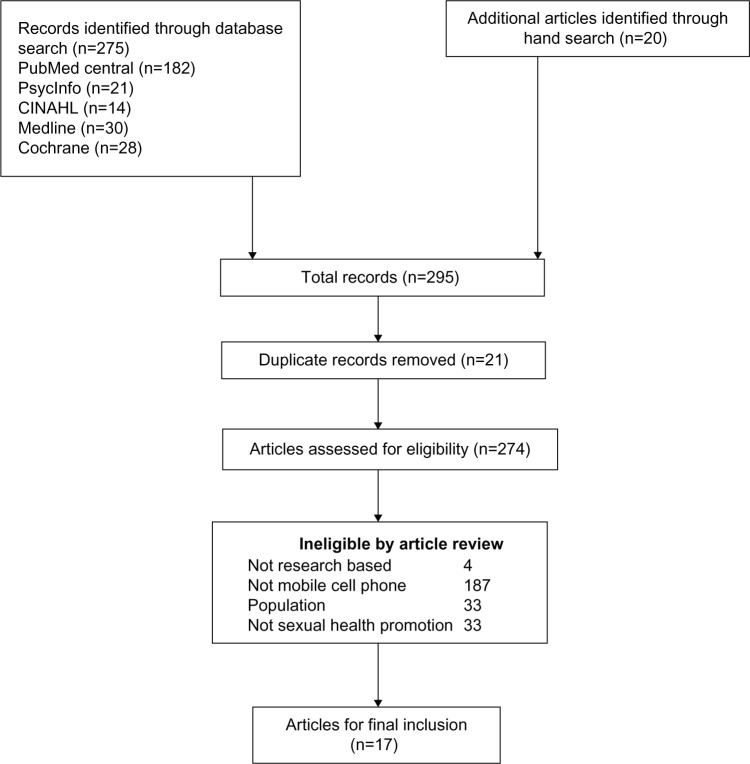

The literature review was conducted using PyscInfo, PubMed, CINAHL, Medline, and Cochrane Review databases from 2010 to 2015. The following search terms were used: research, adolescent, safer sex, sexual education, sexuality programs, and mobile technology (text messaging and mobile phones). Reference lists from each article were reviewed for additional citations, and those meeting the inclusion criteria were added. Relevant studies were also uncovered by doing a manual search in journals that published articles on mobile technology and sexual health. A total of 295 abstracts were retrieved and 17 articles met the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). Each study was read and coded according to the study purpose, design, sample, measures, major findings, and limitations. All extracted data were then read, coded, and discussed by the two authors who compared their coding and preliminary findings to confirm the accuracy of their interpretations for each study (Miles and Huberman).6 Table 1 provides the citations and key components of the studies.

Figure 1.

Inclusion/exclusion data.

Table 1.

Review of the literature

| Authors/Year | Purpose | Design | Sample | Measures | Major findings | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buhi, Klinkenberger, Hughes, Blunt, Rietmeijer (2013)11 | Examine teens’ digital device ownership, online activities, and usage/frequency of communication modalities and the opportunities it presents for STD prevention and sexual health promotion | Quantitative Descriptive |

N=273 February 2010 to January 2011, 13- to 19-year-old individuals recruited from a publicly funded teen clinic in Pinellas County, FL, USA | Adolescents completed ACASI which included 25 questions on demographics, digital device ownership, online activities (Internet access/frequency of use, participation in online games, and SNS activities), and usage/frequency of communication modalities for socializing or communicating with friends To assess feasibility and acceptability, teens were asked how likely they would be to use a text-messaging service, podcasts, blogs, and/or videos either through the Internet or a cell phone for sexual health messages and services |

1. 79% reported daily Internet use, with four of five teens reporting ever having accessed the Internet from a mobile phone 2. Almost a third of teens (31%) reported playing online games, and 8% reported participation in a virtual world 3. When asked about likelihood of using different technologies to find answers to sexual health questions, participants reported they would be likely/very likely to use a text-messaging service (50%), read a blog (48%), watch an online video, such as on YouTube (43%), watch a video on their cell phone (35%), or listen to a podcast (29%) 4. Compared with teens without an STD, teens with a current STD were more likely to report they would be likely/very likely to use a text-messaging service to have questions about sexual health information answered |

1. Current research is limited by a relatively small sample size, recruitment at a single clinic site, and exclusion of youths who did not get tested for STDs or who were not sexually active |

| Cornelius, St Lawrence, Howard, Shah, Poka, McDonald and White (2012)19 | Examine African-American adolescents’ perceptions of a mobile cell phone (MCP)-enhanced intervention and development of an MCP-based HIV prevention intervention | Qualitative | Eleven adolescents (six female, five male) with a mean age of 15.4 years who participated in the Becoming a Responsible Teen Text Messaging project | Adolescents attended seven weekly BART face-to-face sessions, and then they received daily multimedia text messages (pictures, videos, and text messages) for 3 months. Focus group questions included items concerning: MCP-enhanced intervention How did the multimedia MCP text-messaging process make you feel? MCP-based intervention: We are thinking about sending information from the BART intervention solely to your cell phone so that you will not have to come in for the sessions each week. What do you think about this idea? |

1. Adolescents said they benefited from the MCP-enhanced approach 2. Adolescents were receptive to the idea of developing an MCP-based intervention 3. Participants thought of videos as realistic and found this of importance to learning and responding to messages |

1. The study targeted a small sample of African-American youth which may not be generalizable to the general population |

| Cornelius, Cato, St Lawrence, Boyer, and Lightfoot (2011)15 | Develop MCP multimedia text-messaging boosters guided by content in the BART curriculum Assess the feasibility and acceptability of delivering the booster messages to African-American youth |

Quantitative and Qualitative | 12 African-American teens, aged 13–18 years | ADAPT-ITT model used to guide the process of adapting the BART curriculum for MCP multimedia text-messaging Delivery Data collected on the frequency of responses to text messages, pictures, and videos; research team’s attempts to reach participants who fell below an 80% response rate; teens’ recommendations for changes; and the number of teens who found the MCP messaging process intrusive |

1. Average 3-week MCP multimedia text message response rate was 80% 2. Teens reported enjoying the process of the study and were accepting of using MCP multimedia text messages |

1. Use of web browsers and text messaging can be costly 2. Implementation barriers occurred when failure of the internet hosted SMS to send the message at the specified time occurred but was corrected throughout the process |

| Cornelius, Cato, Toth, Bard, Moore, White (2011)23 | The goal for this adaptation was to tailor the BART material for text-messaging boosters. The plan outlined the: a) process of adaptation, b) key information from each BART session for text-messaging delivery, c) materials for developing the messages, d) activities that would be appropriate and relevant for MCP multimedia text-messaging delivery, and e) development of a facilitator’s checklist for text message responses to teens |

Quantitative | Website analysis of a sexual health promotion program (Becoming a Responsible Teen, plus text messaging, BART + TM) | Data collected on website traffic from March 2009 to April 2010 using advanced web statistics 1. How many unique visitors have visited the site? 2. On what days of the week do unique visitors visit the site? 3. At what hours of the day do unique visitors view the site? 4. How long do unique visitors stay on the site (duration)? 5. What are the keywords and phrases used to gain access to the site? 6. What are the entry and exit pages for the website? 7. Who are the unique visitors to the website? |

1. The results indicated that teens were interested in receiving information about safer sex behaviors in their natural settings and with technology, using familiar language 2, 125 unique visitors with an average of 152 per month 3. Website was visited every day of the week but most frequently on Thursdays 4. The total number of pages viewed from March 2009 to April 2010 was 19,038 with an average of 1,360 pages viewed per month |

1. Errors with message delivery and equipment problems, including failure of the Internet-hosted SMS to send the message at the specified time, and MCP problems, such as inability to access the web and inability to receive text messages, were identified and corrected 2. Use of web browsers and text messaging can be costly 3. Findings need to be generalized cautiously, given the small and convenient sample from one geographic area |

| Cornelius J Dmochkowski, Boyer, St Lawrence, Lightfoot, and Moore M (2012)7 | Examine the feasibility and acceptability of an HIV prevention intervention for African-American adolescents delivered via MCPs and look at intervention-related changes in beliefs and sexual behaviors | Longitudinal One group design |

40 African-American adolescents, 13–18 years of age, who provided verbal and written consent, had parental consent to participate, and had knowledge of MCP text-messaging technology | Data collected at three time points: baseline (T1), post-BART at 7 weeks (T2), and at 3-month follow-up post-BART (T3) Daily text messages for 3 months | 1. Findings showed promise in terms of the feasibility and acceptability of this approach. One surprising finding was the high retention rate at the 3-month follow-up. Participants were in frequent contact with the research staff, which may have resulted in this high rate 2. The range of response time for teen participants was 33.7–79.9 minutes and for facilitators it was 29.81–76.78 minutes 3. We found that age was a primary factor in change, with greater increases in knowledge, more improved attitudes toward condoms, more perceived HIV risk, and more reduction in HIV risk behaviors among older participants (16–18 years of age) 4. The differential findings by age suggest that even when presented with the same program, younger adolescents may take away different messages and enact different behaviors |

1. Our pilot feasibility study was limited to short-term follow-up (3 months) and lacked a control group, so we were unable to examine longer-term maintenance of outcomes or definitively say that the positive changes were caused by the intervention 2. Sample consisted of a small group from one geographic location and the results cannot be generalized to other geographic areas 3. The small sample size of study may have prevented detection of longitudinal changes and associations with covariates or interactive effects. Thus, the results of this study have to be interpreted with caution 4. We provided study participants with project Smartphones and, therefore, the acceptability of this approach is limited to the specific MCP used in this project |

| Devine, Bull, Dreisbach and Shlay (2014)16 | Develop and pilot a theory-based, mobile phone texting component attractive to minority youth as a supplement to the Teen Outreach Program® (TOP) | Qualitative and Quantitative | 96 minority youth aged 14–18 years at four sites Before pilot, six focus groups of 59 teens were conducted (30 males and 29 females) | 1. 4-week pilot including surveys (84 questions total) that evaluated values, social support, self-efficacy, and behaviors relating to school performance, trouble with the law, and sexual activity 2. Text sessions covered values, community service, contraception and condoms, and resisting pressure in romantic relationships 3. 11 messages per week sent |

1. We successfully recruited and enrolled minority youth into the pilot 2. Teens were enthusiastic about text messages complementing TOP® |

1. About 15% did not have access to phones for various reasons |

| Fortune, Wright, Juzang, & Bull (2010)10 | To describe methods used to recruit and retain young men in the Black men text messaging prevention program | Quantitative Non randomized two group pilot study with 3 and 6 month follow up |

60 men in the Philadelphia area | Baseline assessments then sent text messages 3 times a week for 12 weeks | 1. Enrolled 58% of the approached Participants 2. Retained 77% to the 3 month follow-up and 65% to the 6 month follow-up |

1. Limited to one geographic location 2. Small sample size |

| France (2014)12 | Text-messaging service was set up in two secondary schools to raise awareness of the school nurse and encourage teenagers to make contact for health advice and support | Quantitative Descriptive |

Adolescents aged 11–16 years | Texts categorized by: Sexual health including puberty and relationships (56%) Emotional health (25%) Physical health (7%) Human papillomavirus (8%) Healthy eating (5%) |

1. 44 out of the 202 text messages led to face-to-face contact with the nurse 2. 93% were aware of the school nurse text service and 63.5% were aware they could access the school nurse via the lunch-time drop-in; 3. 70.2% felt that the text service was a good way to seek help and advice about their health and 63.5% were aware that the school nurse offers a confidential service |

1. Records of text messages were managed by keeping a spreadsheet log which was time- consuming and added administrative work |

| Katz, Rodan, Milligan, Tan, Courtney, Gantz et al (2011)8 | To examine efficacy of a randomized cell phone-based counseling intervention in postponing subsequent pregnancy among teen mothers | Quantitative randomized two-group follow-up to 24 months | 259 15–19-year-old primiparous pregnant teens in the Girl Talk intervention recruited in Washington, DC, USA | Based on the social contextual research tradition and youth asset development model Questionnaire Urine tests |

1. Variability among intervention group teens as to the number of cell phone-based counseling sessions 2. Teens with lost or damaged phones were out of contact for extended periods of time 3. 31% of the intervention group and 36% of the usual care group became pregnant again within 24 months 4. Counseling sessions more effective with teen moms 15–17 years of age but not those of 18 years and older |

1. Program closed before the second year of the operation 2. One geographic location 3. Many teens had few credits to graduate high school |

| Juzang, Fortune, Black, Wright and Bull (2011)9 | To explore the feasibility of recruiting and retaining young black men in a 12-week text-messaging program about HIV prevention | Quantitative Longitudinal Nonrandomized intervention groups |

60 participants aged 16–20 years who self-identified as Black or African-American, sexually active, who own a mobile phone, and live in Philadelphia, PA, USA | Three text messages per week for 12 weeks were sent 3- and 6-month follow-up | 1. The intervention participants showed trends in increased monogamy at follow-up compared to controls 2. Awareness of sexual health was significantly higher in the intervention group. Condom norms were significantly higher for the control group 3. There were no differences in the proportion of protected sex acts. The participants embraced the project, and were enrolled and retained in numbers that suggest such an intervention is worth examining for efficacy |

1. Sample size was small 2. The intervention and control participants were not randomly assigned 3. Condom use levels did not change, but study focused on determination if the text message delivery feasibility |

| Mitchell, Bull, Kiwanuka and Ybarra (2011)18 | Examine who is likely to use text messages, characteristics of adolescents who are utilizing health information via text, characteristics describing adolescents who are most likely to want to access an HIV intervention program via text | Quantitative | 1,503 secondary school students in Mbarara, Uganda, collected in 2008–2009 1,738 adolescents 12–18 years of age were randomly recruited and 1,523 took the survey Survey data a part of the cyber senga study |

Interest in accessing HIV/AIDS information via text messaging Sexual intercourse and HIV Psychosocial and somatic health |

1. 19% of adolescents who had sent or received text messages in the past year indicated that they sent a text message on their cell phone to get information about health and disease in the last 12 months 2. Adolescents more commonly sent a text message to seek information about gossip (29%), television programs (30%), the latest news (45%), and sports (64%) |

1. Rates of cell phone ownership among adolescents in Mbarara, Uganda, are lower than those found among adolescents living in other parts of the country or those living in South Africa |

| Perry, Kayekjian, Braun, Cantu, Sheoran and Chung (2012)20 | To understand adolescents’ perspectives on the use of a preventive sexual health text-messaging service | 26 adolescents aged 15–20 years recruited from two teen clinics in Los Angeles County, CA, USA Weekly text messages of the Hookup service Qualitative |

1. Mixed sex focus groups including 6–13 participants per group for the discussions 2. Participants completed a self-administered written survey prior to groups with the intention for investigators to collect demographic data and stimulate pertinent thoughts before the focus group discussions 3. Items assessing their experiences with the Hookup offered responses on a 5-point Likert scale (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). Example items included: “The messages taught me new things,” “I was embarrassed about having messages related to sexual health in my phone,” and “I was concerned that my parents would see the messages from the Hookup in my phone” |

1. Participants enjoyed receiving weekly text messages related to sexual health. They linked their enjoyment to the message content being informative (providing relevant and new information), simple (automatically limited to small words and short phrases), and sociable (easily able to be shared with friends) 2. Participants also pointed to the convenience and ubiquity of text messaging and generally felt that cost of messages was not a concern. Most felt that text messaging provided a sense of privacy for learning about sensitive health topics, although a few expressed concerns about stigma from peers seeing the messages |

1. Study was limited by self-selection bias of enrollees. Participants were recruited from teen clinics and agreed to participate in a semipublic discussion, which likely shows their knowledge and comfort with sexual health issues is not generalizable to others within the population 2. Few males participated in the study |

|

| Schnall, Okoniewski, Tiase, Low, Rodriguez, and Kaplan (2013)17 | The purpose of this study was to understand the health information needs of adolescents in the context of their everyday lives and assess how they meet their information needs | Mixed methods | 60 adolescents aged 13–18 years | 1. Adolescents were given Smartphones with unlimited text messaging and data for 30 days. Each Smartphone had applications related to asthma, obesity, HIV, and diet preinstalled on the phone 2. Text messages three times per week and asked the following questions: 1) What questions did you have about your health today? 2) Where did you look for an answer (mobile device, mobile application, online, friend, book, or parent)? 3) Was your question answered and how? 4) Anything else? |

1. 90% response rate to text messages. Participants sent a total of 1,935 text messages in response to the ecological momentary assessment questions 2. Adolescents sent a total of 421 text messages related to a health information needs, and 516 text messages related to the source of information to the answers to their questions, which were related to parents, friends, online, mobile apps, teachers, or coaches 3. One participant’s cell phone was stolen but project staff replaced it 4. Two teens had cell phones turned off because they had used the allotted minutes for the month before the month ended 5. Privacy was a concern of the participants |

1. Limitation to our study included a convenience sample that may not be representative of all ethnically diverse adolescents, particularly as they were recruited from one area of NYC 2. Another limitation of our study was the use of EMA. As with all self-report measures, there was no independent check on the veracity of the data because all data were collected in the absence of the experimenter 3. In addition, since the browsing history of our participants was not assessed, responses to the text messages could be inaccurate owing to a number of factors including stigma 4. Technology was limited and did not have a decision tree associated with it to provide responses and feedback to our participants. This may have limited participants’ willingness to continue sharing their health information needs |

| Selkie, Benson, and Moreno (2011)21 | Determine adolescents’ views regarding how new technologies could be used for sexual health education | Qualitative | 29 adolescents aged 14–19 years | Facilitators asked participants for their views regarding use of social networking websites (SNSs) and text messaging for sexual health education. Tape-recorded data were transcribed; transcripts were manually evaluated then discussed to determine thematic consensus | 1. Adolescents preferred sexual health education resources that are accessible 2. Adolescents preferred online resources that are trustworthy 3. Adolescents discussed preference for “safe” resources |

1. Limitations of the study include the small sample size and thus limited generalizability of findings 2. Researchers did not have a reliable method of determining socioeconomic status; thus, results may not be applicable to adolescents from families of all income levels |

| Whiteley, Brown, Swenson, DiClemente, Vanable, Carey, Valois (2011)14 | Examine frequency of cell phone and online media use and its relationship to psychosocial variables and STI/HIV risk behavior | Quantitative | 1,518 African-American, 13–18 years of age From two Northeast US cities (Providence, RI; Syracuse, NY) and two Southeast US cities (Columbia, SC; Macon, GA) Assessed from 2008 to 2009 |

Adapted version of Annenberg Media survey assessed Internet and other media frequency Internet Frequency Scale was created to assess frequency of using the Internet for news, instant messaging, chatting, online journals, social networks, and email 8-item form of Center for Epi Studies Depression scale used to assess symptoms of depression Life Satisfaction Scale Impulsivity Scale Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale Subjective Peer Norms for Sexual Risk Behavior scale |

1. Over 90% of African-American adolescents used cell phones every day or most days and 60% used social networking sites every day or most days (96% used Myspace) 2. Greater frequency of cell phone use was associated with sexual sensation seeking (P=0.000), riskier peer sexual norms (P=0.000), and impulsivity (P=0.016). Greater frequency of Internet use was associated with a history of oral/vaginal/anal sex (OR =1.03, 95% CI=1.0–1.05) and sexual sensation seeking (P=0.000) 3. Riskier youth are online and using cell phone frequently |

1. Measures used are derived from a parent study – Project iMPPACS; limited measurement of specific types of Internet and cell phone interactions 2. Participants enrolled in HIV preventive-intervention and may not be representative of the entire African American adolescent population |

| Willoughby & Jackson, (2013)13 | Analysis of text messages from the BrdsNBz text message service | Quantitative Descriptive |

1,351 text messages sent to a sexual health text message service | Topics: Sexual health Sexual technique Relationship Service Other |

1. Majority of questions were about sexual health (81.6%) and sexual acts 2. Questions about STDs did not come up as frequently as other topics (unplanned pregnancy) 3. Half of the STD questions were of general knowledge |

1. Analysis of one text message service 2. Unable to obtain demographic characteristics of participants |

| Wright, Fortune, Juzang and Bull (2011)22 | Examine the feasibility of using cell phones for HIV prevention in the population | Qualitative | 43 men aged 16–20 years | Six focus groups conducted over a 3-month period to document reactions to and preferences for a text message-based HIV prevention program Feedback was sought on how to best convey outcomes for our intervention pertaining to sexual health: increasing condom use, practicing monogamy, and/or staying abstinent Feedback sought on how to operationalize five theoretical constructs in text messages: providing information on and awareness of HIV/AIDS, promoting positive attitudes toward sexual health, condom use norms, intentions to stay safe, and skills that would best help achieve positive outcomes |

1. Young black men were receptive to the idea of receiving text messages for an HIV prevention campaign 2. Participants suggested that the men involved in the pilot study should receive only three messages a week, preferably after they had finished school for the day 3. Men wanted to be challenged to think critically about the messages and preferred messages that would “ask more of a question” than make a comment 4. Participants helped shape operationalization of key theoretical constructs, such as incorporating aspects of empowerment and social capital into the campaign |

1. Focus group findings represent only the ideas and feedback of the men who participated in the groups, and cannot be generalized to the larger population of 16- to 20-year-old men in the US 2. Not all of the young men owned cell phones who gave feedback on the program despite being an inclusion criterion for the program |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SMS, short messaging service; STI, sexually transmitted infection; NYC, New York city; EMA, ecological moment assessment; ACASi, audio computer assisted self-interview.

Results

Study designs

Ten of the 17 studies used quantitative methods. Four studies were longitudinal with repeated measures7–10 and the other quantitative studies used descriptive or cross-sectional designs.11–14 One study was a randomized trial;8 the others were a one-group pre-/posttest design7 and a nonrandomized control group design.9 Three studies used mixed methods,15–17 one was constructed in Africa18 and the others used qualitative designs, with interviews or focus groups.19–22 Intervention lengths varied from 4 weeks16,17 to 3 months.7,9,10 Text messaging or mobile cell phone follow-up periods ranged from posttest,16,17 weekly,7,9 3 months9,11,22 to 24 months8; most studies were formative or pilot studies, and used validated measures to assess intervention outcomes. All studies used self-reported data with the exception of two; one used STI biomarkers in addition to self-reported data11 and the other used early pregnancy tests in addition to self-reported data.8 Sample sizes varied from eleven to 1,738 participants. Four studies discussed theories used to guide development of the text messages/interventions.10,15,16,22 These theories included empowerment theory, social capital theory, theory of reasoned action, health belief model,10,22 youth asset developmental theory,16 and ADAPT-ITT model.15 The text-messaging dosage varied among interventions from one message per day,7,11 weekly,20 three per week9,10 to eleven per week.17 Mobile cell phone counseling calls occurred once weekly.8 Only one study discussed analysis of an HIV-prevention website enhanced for mobile cell phone text-messaging delivery.23 Over a 14-month time period, the website had a total of 2,125 unique visitors from 61 different countries. Another study discussed data from a sexual health text message service designed for youth to determine the type of confidential questions asked by participants.13

Delivery process

Several studies identified challenges involved in the development of text messages for mobile cell phone delivery. In one study, participants noted that some of the text-messaging abbreviations were not helpful.15 Further, areas of inaccuracy and confusion were found. For example, one teen was unsure whether mosquitoes could transmit HIV even after the correct information was provided. Whenever teens got the answer wrong, they felt they should be able to text a facilitator to clarify why the response was wrong. In another study, participants felt that the initial text messages blamed or stigmatized the African-American community and recommended that messages be geared to the young black population.22 Participants also noted that messages should be factual, respectful, and humorous. One suggested format was starting with humor, then finishing with a fact. Participants in one study found that a mobile phone application (app) was difficult to read and use, was not tailored to the intended population, and raised privacy issues.17

Technical problems also presented challenges.15,17 In one study, the research team identified errors in the message delivery process as well as equipment problems, including failure of the short messaging service to send the message at the specified time, inability to receive text messages, and failure to respond to the messages as the result of a lost or damaged cell phone.15 All of the problems were corrected, however. In the same study, problems in downloading videos or viewing URL links were found to be challenges. The researchers noted, however, that including a tech facilitator on the research team who could quickly correct problems reduced frustration and dropout rates.15 In one study, the researchers found that they had to replace a participant’s phone, which had been stolen, and had to turn off two cell phones when teens went over their allocated minutes before the end of the month.17 In another study, some teens lost or damaged their phones or were out of contact for an extended period of time resulting in considerable variability in participation rates.8

The cost of delivering text-messaging interventions was also a challenge and in two studies, mobile cell phones were given to participants to offset costs.15,17 However, given current unlimited text-messaging plan, this is no longer a major barrier to adoption of text-messaging interventions. In the Teen Outreach Program, the buddy system was used. Teens with a mobile phone shared their phone or read the messages to a peer (their buddy) who did not have access to a mobile phone. This process did not work uniformly with some teens deleting messages before their buddy could read them.16 In another study, the mobile phone incentive diminished as the low cost of prepaid cell phones became readily available and many of the teens purchased their own personal cell phone by the end of the study.17

Lack of longitudinal studies

Only two of the studies reported outcomes beyond the 3-month follow-up9,10 and only one included 24-month follow-up.8 Thus, only short-term effects of mobile cell phone interventions have been reported. Juzang et al9 found significant changes in three key outcomes: higher condom use, increased sexual health awareness, and increased monogamy postintervention. In another study, HIV knowledge, attitudes toward condom use, and perceived HIV risk increased while HIV risk behaviors decreased at 3-month follow-up.7

Privacy issues

In two studies, adolescents identified issues of privacy and lack of anonymity as possible challenges in delivering text messages/mobile cell phone interventions.17,21 In one study, no participants said that they would feel embarrassed if someone viewed their messages and 90% were unconcerned if their parents saw their messages.21 However, they did say that privacy could be compromised, which could make a situation uncomfortable for a teen. In another study, privacy was a consideration with the use of a mobile cell phone safe sex app since participants felt that the research team could see what they were doing with the phones.17

Need for tailored messages

In a follow-up to a mobile cell phone app study, Schnall et al7 found that adolescents 13–18 years of age viewed the app as hard to understand and complicated to use, and thus felt that the app was not tailored to adolescents. This finding is consistent with the conclusion of Selkie et al21 that sexual health resources must be written in clear, understandable language and tailored to adolescents. In addition, Wright et al22 found that their adolescent participants wanted mobile cell phone text messages about STIs, including HIV/AIDS, to be factual and specific to them.

Credible information

Trust in the information and having someone qualified to respond to questions were found to be challenges in four studies.9,15–17 Participants in one study felt that knowing a person was qualified to answer their questions was important in accessing information using mobile cell phones.21 In another study, the participants unanimously agreed that they should be able to text questions to their facilitator.15 In one study, trained staff members from the Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Campaign provided medically accurate responses to text messages within 24 hours: typical responses occurred within 3–4 hours.16 The cost of having a staff member to answer individual questions may be an issue for community-based agencies. Yet, youth want an immediate answer to a sexual health question that arises.7,21 Automatic standard responses may not always provide an appropriate response or one detailed enough to answer the question.

Impact of age on study outcomes

In one study, the way text messages were perceived varied depending on the age of the participants. Cornelius et al7 found that age was a primary factor in change in outcome variables. They found greater increases in knowledge, attitudes toward condom use and perceived HIV risk, and more reduction in HIV risk behaviors among older participants (16–18 years of age) than younger participants (13–15 years of age). The reason why text messages did not resonant among younger participants was unclear. However, the younger participants did report less sexual activity than the older teens, which could explain why the messages did not resonate with them.

Adaptation to other countries: limited access

Adaptation of mobile cell phone-based interventions to other countries has presented challenges. One of the concerns with technology-based interventions is that we may not reach those who are at the highest risk, partly because of economics and access to services and technology. With low mobile cell phone ownership rates among adolescents in Uganda, only 51% of the participants in one study indicated that they were somewhat or extremely likely to access HIV/AIDS information via text.18 Interest in accessing this information was associated with owning a cell phone. Thus, those at the highest risk may not be able to access cell phones because of the cost of the phone or text messages or data plans.

Use of health care providers

Only one study identified ways in which health care providers can use a text-messaging service to connect with youth. France examined how a school nurse used text messages to provide students access to her health promotion services.12 The challenges with this approach involved administrative time and costs in managing and recording text messages. Advantages to the approach included the fact that it enhanced health services at the school and involved youth by empowering them to become knowledgeable about their sexual health. However, the approach was limited to students who owned or had access to a cell phone. Those without a cell phone did not have access to the services.

Discussion

Only 17 published articles were found that examined use of mobile cell technology and sexual health. The majority of the articles were descriptive studies that reported text messaging as the primary mode of sending or receiving sexual health information. Only four articles provided findings from a longitudinal study, and these findings were limited to 3–24 months. One study used a one-group design, one was a randomized trial, and one used a nonrandomized control group design.

Our review nonetheless suggests that mobile cell phone interventions are an effective mode for delivering safe sex and sexual health information to youth. However, while studies have demonstrated the potential of delivering sexual health information via mobile technology, there is still much to be learned about optimizing this intervention channel. More randomized controlled trials are needed to examine longitudinal effects and varying doses of text messages. Further, one study7 has identified possible differential effects of text messaging depending on age. The younger teens in this study also reported less sexual activity than the older teens, which may explain why the messages did not resonate with younger teens. Therefore, it is important to know the population for whom messages are developed: not all messages can be applied to everyone.

Teens want an immediate response to a text message. Automation may be appropriate in many situations, but there are times when a question or the response is not in the database or repository of a sexual health program. It is a challenge to provide real-time responses from staff, but this maybe the only way to be able to provide an answer to every question that may be texted to a sexual health program. Programs such as Hookup20 and BrdsNBz13 have found success in providing text-automated responses to messages but data are limited on the long-term effectiveness of these programs.

There is a cost for delivering mobile cell phone messages or interventions. Participants and staff must have working equipment and unlimited text messaging and data plans. Those most at risk may not have cell phones and may not be able to access safe sex messages; therefore, alterative means for delivering safer sex messages must be found. Further, lost or damaged equipment remains a challenge and research staff may need to provide phones on loan to reduce dropout rates in studies.

Recommendations

Excessive use of text messaging affects adolescent social development negatively.24 It would be interesting to do a longitudinal study to see whether text messaging drops off when social skills develop. Case scenarios could be developed to see how participants interact with others, measuring eye contact, word fillers, and body language against their text-messaging rates.24

Currently, text messaging is an acceptable form of receiving sexual health information among adolescents, but in this review, we found no studies with follow-up beyond 24 months. Future studies should examine participant attrition, plans for improving retention, and message boosting to encourage maintenance of behavior change. In one study7 the researchers sent text-messaging boosters to augment a face-to-face intervention, and this enhanced effects. We must also begin to investigate other sources of sexual health communication. Currently, social media networks are being examined as potential sexual health information sources among adolescents. Platforms deploying multiple technologies may be particularly successful. For example, with a social media intervention that uses multiple sites, youth only need to log into one site. Given the long interval between mobile cell phone intervention development and dissemination, it is also important to assess not only the current user population but also potential future populations.

Sexual health interventions should go where the population goes. Real time interventions will have the greatest impact. As newer types of media become increasingly available and used by adolescents, it may be important to study different types of cell phone interactions and their associations with sensation seeking and impulsivity.

The lack of theory-based interventions found in this review may reflect the current focus on clinical care rather than on preventive health behavior change. However, interventions built on theory may have the greatest potential to change behavior and empower youth with the skills to practice abstinence or safe sex behaviors. Further, as technologies continue to develop, assessments should be performed prior to launching a program using new technology to ensure that the technology platform is still relevant to the target audience. New technology should augment, not replace existing resources.

Only one study23 reviewed here identified dissemination of a mobile safe sex information via a website. The website augmented information from an intervention and demonstrated one method of broad dissemination of safe sex information for adolescents. This website had a global impact, reaching unique users in 61 different countries. Future research should further examine the global impact of text-messaging interventions with participants in different countries.

More research is also needed to examine technology-based sexual communications among youth, since these have implications for adolescents’ safe sex decision-making. Timing, quality, length, and commitment of relationships should be examined with the mobile cell phone communication process. In addition, parent–child mobile cell phone-based interventions may improve adolescents’ safe sex decision-making since parents have been identified as a factor in the delay of their child’s sexual debut.

Further, we need to examine sexting behaviors across geographic regions by format (photo, text) and medium (cell phone, email, etc) and relationships to sexual activities. Future research should also examine parents’ perceptions of their child’s cell phone use and compare this with the child’s actual self-reported usage for sexual risks. Since sexting has been identified as a prelude to sexual intercourse, parents and health care providers should begin discussions of technology use with teens to identify possible sexual risks. Finally, research is needed to find out what youth do with the information that they use on text-generated sites (such as Hookup and SexInfo) and the extent in which the information is found helpful.

One strength of this review is the multiple strategy search process used. Further, the time frame was limited to the last 5 years, providing the most recent studies on this topic. The limitations of the review include the fact that many of the studies reviewed were pilot or exploratory studies with small purposive samples limiting generalizability of the findings. In addition, the review was limited by having only one article from Africa, where rates of HIV infection are the highest in the world.

Conclusion

This systematic review provides useful information on the impact of technology on the delivery of safe sex information to youth. Additional research is needed to identify the most effective approaches to using mobile cell phones as a vehicle for providing sexual health information to youth. There remain challenges, however, in the delivery of mobile cell phone safe sex interventions. One challenge is that young participants may not own a cell phone or have access to one. Another is that we do not know about the long-term effectiveness of mobile phone sexual health interventions. Further, messages must be tailored to the targeted population who need to be involved with the research planning from the ground up. Technical problems must be identified early and corrected as soon as possible to prevent attrition; this may require the constant presence of a technology specialist with the project. Finally, some text messages or data plans may incur a cost, which could be a barrier to implementation.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC fact sheet: Incidence, prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States. [Accessed September 22, 2015]. Published February 2013. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/sti-estimates-fact-sheet-feb-2013.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Youth behavior surveillance survey. 2015. [Accessed September 22, 2015]. Published May 15, 2015. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/index.htm.

- 3.Pew Research Center Teens and technology 2013. [Accessed September 22, 2015]. Published March 13, 2013. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2013/PIP_TeensandTechnology2013.pdf.

- 4.National Institutes of Health Frequently asked questions. [Accessed September 22, 2015]. Published March 17, 1999. Available from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/children/pol_children_qa.htm.

- 5.World Health Organization Adolescent health. [Accessed September 22, 2015]. Published 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/

- 6.Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cornelius JB, Dmochowski J, Boyer C, Lawrence JS, Lightfoot M, Moore M. Text messaging enhanced HIV interventions for African American adolescents: a feasibility study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;24(3):256–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz KS, Rodan M, Milligan R, Tan S, Courtney L, et al. Efficacy of a randomized cell phone-based counseling intervention in postponing subsequent pregnancy among teen mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S42–S53. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juzang I, Fortune T, Black S, Wright E, Bull S. A pilot programme using mobile phones for HIV prevention. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(3):150–153. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.091107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortune T, Wright E, Juzang I, Bull S. Recruitment, enrollment, and retention of young black men for HIV prevention research: experiences from the 411 for Safe Text Project. Contem Clin Trials. 2010;31:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buhi ER, Klinkenberger N, Hughes S, Blunt HD, Rietmeijer C. Teens’ use of digital technologies and preferences for receiving STD prevention and sexual health promotion messages: implications for the next generation of intervention initiatives. Sex Trans Dis. 2013;40(1):52–54. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318264914a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.France J. Using texts to increase access to school nurses. Nurs Times. 2014;110(13):18–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willoughby JF, Jackson K. Can you get pregnant when u r in the pool? Young people’s information seeking from a sexual health text line. Sex Ed. 2013;13(1):96–106. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiteley LB, Brown LK, Swenson, et al. African American adolescents and new media: associations with HIV/STI risk behavior and psychosocial variables. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(2):216–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornelius JB, Cato M, Lawrence JS, Boyer CB, Lightfoot M. Development and pretesting multimedia HIV-prevention text messages for mobile cell phone delivery. J Assoc Nurs AIDS Care. 2011;22(5):407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devine S, Bull S, Dreisbach S, Shlay J. Enhancing a teen pregnancy prevention program with text messaging: Engaging minority youth to develop TOP® Plus Text. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(3):S78–S83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnall R, Okoniewski A, Tiase V, Low A, Rodriguez M, Kaplan S. Using text messaging to assess adolescents’ health information needs: an ecological momentary assessment. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(3):1–16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell KJ, Bull S, Kiwanuka J, Ybarra ML. Cell phone usage among adolescents in Uganda: acceptability for relaying health information. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(5):770–781. doi: 10.1093/her/cyr022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornelius JB, Lawrence JS, Howard JC, et al. Adolescents’ perceptions of a mobile cell phone text messaging-enhanced intervention and development of a mobile cell phone-based HIV prevention intervention. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2012;17:61–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perry RC, Kayekjian KC, Braun RA, Cantu M, Sheoran B, Chung PJ. Adolescents’ perspectives on the use of a text messaging service for preventive sexual health promotion. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(3):220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selkie EM, Benson M, Moreno M. Adolescents’ views regarding uses of social networking websites and text messaging for adolescent sexual health education. Am J Health Educ. 2011;42(4):205–212. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2011.10599189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright E, Fortune T, Juzang I, Bull S. Text messaging for HIV prevention with young Black men: formative research and campaign development. AIDS Care. 2011;23(5):534–541. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.524190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornelius JB, Cato MG, Toth JL, Bard PM, Moore MW, White A. Following the trail of an HIV-prevention web site enhanced for mobile cell phone text messaging delivery. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23(3):255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaBode V. Text messaging: one step forward for phone companies, one leap backward for adolescence. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2011;23(1):65–71. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2011.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]