ABSTRACT

The transfer of genetic information from RNA to DNA is considered an extraordinary process in molecular biology. Despite the fact that cells transcribe abundant amount of RNA with a wide range of functions, it has been difficult to uncover whether RNA can serve as a template for DNA repair and recombination. An increasing number of experimental evidences suggest a direct role of RNA in DNA modification. Recently, we demonstrated that endogenous transcript RNA can serve as a template to repair a DNA double-strand break (DSB), the most harmful DNA lesion, not only indirectly via formation of a DNA copy (cDNA) intermediate, but also directly in a homology driven mechanism in budding yeast. These results point out that the transfer of genetic information from RNA to DNA is more general than previously thought. We found that transcript RNA is more efficient in repairing a DSB in its own DNA (in cis) than in a homologous but ectopic locus (in trans). Here, we summarize current knowledge about the process of RNA-driven DNA repair and recombination, and provide further data in support of our model of DSB repair by transcript RNA in cis. We show that a DSB is precisely repaired predominately by transcript RNA and not by residual cDNA in conditions in which formation of cDNA by reverse transcription is inhibited. Additionally, we demonstrate that defects in ribonuclease (RNase) H stimulate precise DSB repair by homologous RNA or cDNA sequence, and not by homologous DNA sequence carried on a plasmid. These results highlight an antagonistic role of RNase H in RNA-DNA recombination. Ultimately, we discuss several questions that should be addressed to better understand mechanisms and implications of RNA-templated DNA repair and recombination.

KEYWORDS: Double-strand break, homologous recombination, RNA-templated DNA repair, RNase H, transcript RNA

Transfer of genetic information from RNA to DNA: Theory and supporting evidence

Can RNA transfer genetic information to DNA beyond the special cases of retroviruses, retrotransposons and telomere synthesis1.,2.?1,2 Can RNA recombine with DNA either directly or indirectly if converted into cDNA? Studies on reverse transcription mediated by retrotransposons of yeast (Tys), or of insects (R2), have shown that not only RNA originating from retroelements could be reverse transcribed but potentially any RNA,3 such as the RNA deriving from the yeast HIS3 marker gene, and that RNA could mediate recombination with DNA and modify genomic DNA once converted into cDNA via reverse transcription.4-6 It was found that not only Ty cDNA, but also HIS3 cDNA could recombine with homologous or homeologous (partially homologous) DNA,6 integrate into genomic DNA if fused to transposon sequences, or be captured at sites of chromosomal DSBs via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ).7,8 Additional studies in yeast revealed involvement of cDNA in homologous recombination (HR),9-11 and it was suggested that different types of reverse transcription products including ssDNA and RNA-DNA hybrids could be engaged in recombination.12 Further work in mammalian cells showed that Long INterspersed Elements (LINEs) can be captured at sites of DNA damage, and that retrotransposition of LINEs can carry fragments at their ends that are derived from reverse transcription of endogenous mRNA.13-15

There has been a series of hypotheses and speculations that RNA can work as a template in DNA recombination and repair.16 Recombination mediated by reverse transcripts of cellular RNAs with homologous DNA has been suggested to explain the paucity of introns in yeast genomic DNA, while end-joining-driven insertions of cDNA products could explain the abundance of pseudogenes in multicellular eukaryotes.17,18 Indeed mRNA-mediated intron losses were shown to occur in yeast mitochondrial DNA19 (and references therein). Murakami et al. suggested a mechanism of RNA-directed DNA repair in mitochondria facilitated by the reverse transcriptase activity of DNA polymerase gamma,20 whereas possible mechanisms of DSB repair in nuclear DNA by RNA have been proposed by Trott and Porter.21 The discovery of a widespread type of viral genome representing a chimera between an RNA and a DNA virus has inferred the occurrence of RNA-DNA recombination between two quite different virus groups.22,23 From work in plants, Xu et al. proposed a direct or indirect RNA-templated DSB repair mechanism via gene conversion to explain the observed high frequency of gene homozygosity in rice.24 Furthermore, a recent study reported that DSBs in neurons of young adult mice can be part of normal brain functions such as learning, as long as the DSBs are controlled and repaired in short time.25 Could RNA serve as template for DNA repair of these physiological DSBs in neurons? It has been proposed that flow of information from RNA to DNA could lead to DNA recoding events in the nervous system and could be the basis for permanent storage of long term memories.26,27

Considering the abundance of RNA in cells, the flow of genetic information from RNA to DNA could strongly affect genome stability, either by increasing or decreasing it, depending on the circumstances. Different experimental insights suggest that mechanisms of RNA-driven DNA modification might be more common than is currently recognized. Evidence of RNA-derived insertions came from analysis of sequences at DSB sites in fruit fly and mammalian cells. An exon–exon junction sequence was found from the analysis of DNA sequences repaired via NHEJ after DSB induction by zinc-finger nucleases in Drosophila cells,28 suggesting a direct or indirect RNA-templated insertion mechanism. Work in human cells revealed presence of murine sequences derived from murine RNA that was co-transfected into the human cells together with the DNA of the I-SceI DSB-inducing vector.29 More recently, exonic RNA insertions were detected in knock-in mouse experiments at sites of DNA DSBs generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 system.30 Overall, these studies showed that insertions of RNA derived sequences can result in an error-prone form of DNA repair, which may play a role in genetic disorders and evolution.

Is there experimental proof for RNA-DNA recombination and RNA-mediated DNA repair that is homology driven?

Can RNA directly mediate genetic DNA modifications in a homology-driven manner? Can RNA repair a DSB in homologous DNA sequences? Experiments in budding yeast showed that not only short ribonucleotide tracts carried within synthetic DNA oligonucleotides (oligos) but also RNA-only oligos can precisely repair a DSB in homologous DNA, serving as direct templates for DNA synthesis at the chromosomal level, and transferring genetic information also in conditions in which Ty reverse transcription is repressed.31-33 The capacity of short RNA patches to directly modify DNA was also found in the bacterium Escherichia coli,34,35 and RNA oligos could precisely repair a DSB in the green fluorescent protein gene in human embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells.35

As a model to explain the occurrence of transgenerational inheritance of genomic DNA rearrangements in ciliated protozoa, Angeleska et al. proposed a mechanism in which RNA molecules, single- or double-stranded (ss or ds), act as template catalyst to guide specific recombination events.36 The model for RNA-templated DNA rearrangements was then tested using long synthetic RNA sequences injected into the ciliate Oxytricha trifallax and the RNA templates were found to mediate correct and precise DNA rearrangements.37,38 In addition, mutations carried on the artificial RNA templates were transferred to the homologous endogenous DNA sequences suggesting a process of RNA-guided DNA repair in O. trifallax.37

Models of RNA-DNA HR are supported by biochemical studies, showing the ability of the E. coli recombinase RecA to promote pairing between duplex DNA and ssRNA in vitro.39–42 Moreover, recent work suggests that the eukaryotic RecA homolog, Rad51, can also promote formation of RNA-DNA hybrids in yeast.43

Beyond the demonstration that synthetic RNA molecules introduced into cells can mediate HR with DNA, our recent work showed that endogenous transcript RNA can be a template for DSB repair and HR in yeast.44 We provided experimental evidence that the transfer of genetic information from RNA to DNA occurs with an endogenous generic transcript, and is thus a broader phenomenon than previously anticipated.

Transcript RNA mediates DSB repair in a homology-driven manner

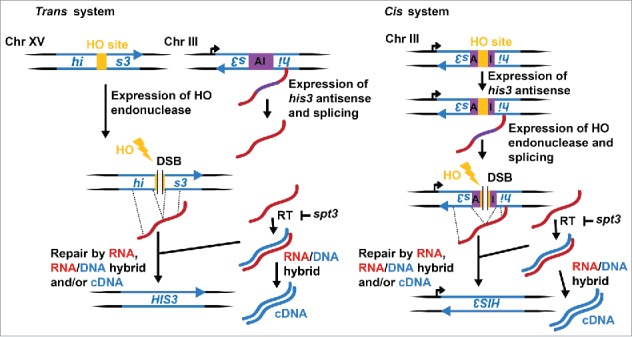

We developed a system to explore the prospects of an endogenous RNA transcript ability to serve as a template for the repair of DSBs, casting a new light on the roles of RNA in the DNA damage response.44 Our strategy is based on the induction of a DSB located inside a nonfunctional his3 marker gene, and successive DSB repair via an endogenous spliced transcript RNA resulting in histidine prototrophic (His+) cells. We engineered cis and trans systems granting the possibility to evaluate the effects of localization and continuous productions of the transcript RNA. The cis system transcribes an antisense his3 sequence with an artificial intron inserted in the antisense orientation that upon galactose induction results in a spliced antisense his3 transcript that can facilitate repair of a DSB located inside the artificial intron resulting in a functional HIS3 locus. The artificial intron (105 bp) contains the site for the HO endonuclease (124 bp); in total, a 229-bp insert disrupts the HIS3 gene. Likewise, the trans system is based on dual his3 loci, in which, one locus is the endogenous HIS3 gene on chromosome XV but disrupted by the cutting site of the HO endonuclease, and the other locus is located on chromosome III and serves to produce an antisense his3 transcript with an artificial intron inserted in the antisense orientation that upon galactose induction produces a his3 antisense transcript that can aid in the repair of the DSB generated at the HO site of the endogenous HIS3 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of the trans and cis systems. HO, homothallic switching endonuclease (yellow); AI, artificial intron (purple); right turn arrow, pGAL1; yellow lightning bolt, cleavage activity by HO; RT, reverse transcriptase.

Considering the abundance of retrotransposons in the yeast genome,45 we sought to eliminate the reverse transcription activities associated with retroelements to explore the ability of RNA to serve directly as a template for repair rather than through the cDNA intermediates of retrotransposition. To this end, we created an spt3-null mutant, which prevents normal Ty transcription and reduces Ty transposition.46 As a result, in spt3-null mutant yeast, no His+ colonies are observed suggesting that cDNA-mediated repair is the major pathway of repair in transposition proficient cells.44 This indicates that any actively transcribed gene can be repaired using a reverse transcribed cDNA template. Because an RNA-DNA heteroduplex is a probable prerequisite for RNA to recombine directly with DNA, we sought to facilitate stable formation of RNA-DNA hybrids by deletion of RNase H1 (RNH1) and the catalytic subunit of RNase H2 (RNH201) genes, which both code for non-sequence-specific endonucleases that cleave RNA backbone of RNA-DNA hybrids.47 Deletion of both RNH1 and RNH201 results in a 5-fold increase of His+ colonies in trans and a 35-fold increase in cis. Surprisingly, the spt3 rnh1 rnh201 genotype results in more than 69,000 His+ colonies than in spt3 single mutant, and even more intriguingly, the cis system of the spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells yields 10-fold more His+ colonies than the trans system, which continuously produces transcript for repair.44 Furthermore, deletion of the RAD52 gene, which codes for an important homologous recombination protein facilitating the annealing of complementary ssDNA, results in a strong reduction of His+ colonies in spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells.44 A complementary in vitro study suggests that yeast and human Rad52 can promote the annealing of RNA to DNA, and in the presence of RPA, even more efficiently than DNA to DNA.44 Thus, we propose a model that upon the occurrence of a DSB in a transcribed DNA, Rad52 promotes the annealing of RNA to DNA, and, in the absence of RNases H, RNA serves as a template bridging the broken DNA ends to promote precise re-ligation, or allowing extension of the broken 3′ end via reverse transcription.44 Given the prerequisite that our assay requires a spliced mRNA to display a phenotype, we could be missing repair by unspliced mRNA, thus RNA-templated DNA modifications may have a substantial impacts on genomic stability.

DNA self-repair by transcript RNA

Our results of DSB repair in the cis and trans systems showed that the frequency of His+ colonies in cis spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells was >69,000-fold higher than in cis spt3 cells, and >10 -fold higher than in trans spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells.44 Is this high frequency of His+ colonies in cis spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells due to the RNA functioning as homologous template to mediate a precise re-ligation of the broken DSB ends? Alternatively, is this repair templated by cDNA due to residual Ty activity? We showed that the DSB repair at the his3 locus in cis spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells was predominately mediated by transcript RNA rather than cDNA.44 Here, we corroborate our finding that transcript RNA can directly serve as a template for repair of a DSB occurring in the same DNA that generated the transcript in spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells of the cis system.

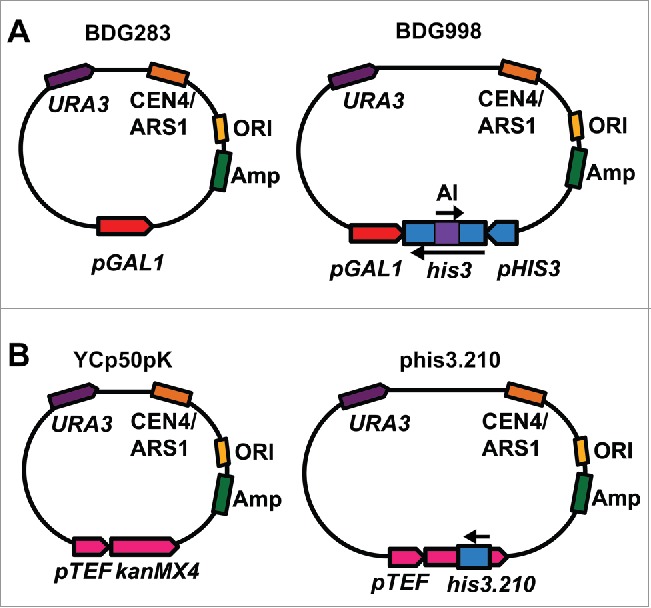

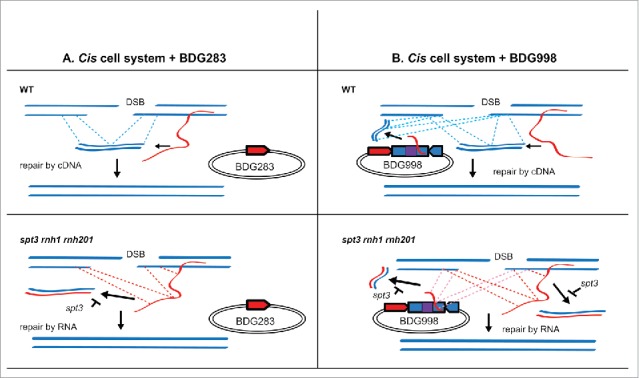

We examined the effect of an extra copy of the his3 allele, disrupted by the artificial intron in the antisense orientation (mhis3-AI) carried on a yeast centromeric plasmid (BDG998) (Fig. 2A), on the frequency of His+ colonies following DSB induction in wild-type and spt3 rnh1 rnh201 backgrounds of the cis system. We transformed wild-type and spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells with low copy number plasmid BDG998 or with the control empty plasmid (BDG283), which carry the URA3 marker gene (Fig. 2A), and selected for colonies able to grow on medium lacking uracil (Ura+ colonies). We then performed the fluctuation assay as described in Materials and Methods and in.44 In wild-type cells, the His+ frequency was strongly increased in the presence of the BDG998 plasmid (Table 1 and Fig. 3) compared to BDG283-containing cells. This was expected because not only the his3 antisense transcribed from the chromosomal his3 copy, but also the one transcribed from the his3 copy carried on the BDG998 plasmid can be converted into cDNA by Ty reverse transcriptase and provide additional copies for DSB repair. Moreover, differently from the chromosomal copy, the plasmid copy of his3 can continue to be transcribed in galactose medium because it does not contain the site for the HO endonuclease within the artificial intron, thus, it can generate lots of cDNA molecules. In contrast, there is no significant difference in the frequency of His+ colonies between spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells containing BDG283 and BDG998 (Table 1 and Fig. 3). If cDNA would be the major template for his3 repair in spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells we would expect higher frequency of His+ colonies also when these cells contain BDG998 than in cells containing BDG283. These data suggest that even if there is residual cDNA in cis spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells, cDNA does not play a major role in DSB repair of the his3 locus. Rather, it is the transcript RNA from the chromosomal locus that mediates, in cis, most of DSB repair to restore the function of its broken his3 gene on the chromosome.

Figure 2.

Scheme of the plasmids introduced in the cis system. A) BDG283 and BDG998. GAL1 promoter, pGAL1 (red); his3 promoter and open-reading frame, pHIS3 and his3 (blue); AI, artificial intron (purple). The arrows indicate the orientation of the AI and that of the his3 gene. Other parts of the plasmids are also shown. B) YCp50pK and phis3.210. The kanMX4 gene with the pTEF promoter are in pink; 210-bp fragment of HIS3 sequence, his3.210 (blue) is inserted in the kanMX4 gene. The orientation of the his3 fragment is indicated by an arrow. Other parts of the plasmids are also shown.

Table 1.

Transcript RNA-templated repair is the major mechanism for precise DSB repair in spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells in cis system.

| Genotype of cis system | His+ freq. | Survival | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT + BDG283 | 33 | (20–45) | 9% |

| WT + BDG998 | 4,130 | (2,680–6,190) | 10% |

| spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + BDG283 | 870 | (706–960) | 22% |

| spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + BDG998 | 890 | (850–980) | 27% |

Frequencies of His+ colonies per 107 viable cells for yeast strains of the cis system of the indicated genotypes and containing either the control empty vector BDG283 or vector BDG998, following 48 h of galactose treatment are shown as median and 95% CI (in parentheses). Percentage of cell survival after incubation on galactose is also shown. There were 9–12 repeats for each strain. The significance of comparisons between different strains of the system was calculated using the Mann-Whitney U-test and it is shown in Table 3A. Fig. 3 serves as graphical guide for all results presented in this table.

Figure 3.

Templates for DSB repair in his3 locus to generate a functional HIS3 gene in a trans-cis system. This figure reflects the results of Table 1. Only repair mechanisms resulting in functional restoration of HIS3 are shown. Repair may also proceed by canonical NHEJ or HR with sister chromatid but does not result in functional HIS3. Regions of homology to the DSB site in his3 are shown as dashed lines. The spt3-null mutation results in inhibition of reverse transcription by Ty retroelements. Relevant genotypes are shown in the top left corner of each panel. Donor molecules that can serve as template for DSB repair are shown as solid blue lines for cDNA and dsDNA, red and blue lines for RNA/DNA hybrid, and red lines for transcript-RNA. A) Repair of a DSB in cis system in the presence of BDG283. B) Repair of a DSB in cis system in the presence of BDG998. DSB repair in trans templated by the spliced RNA from the transcription of his3 on BDG998 is also possible in cells containing rnh1 rnh201 mutations, although this is inefficient.

Defects in RNase H activity stimulate homology-driven DSB repair by cDNA and RNA, but not by plasmid DNA

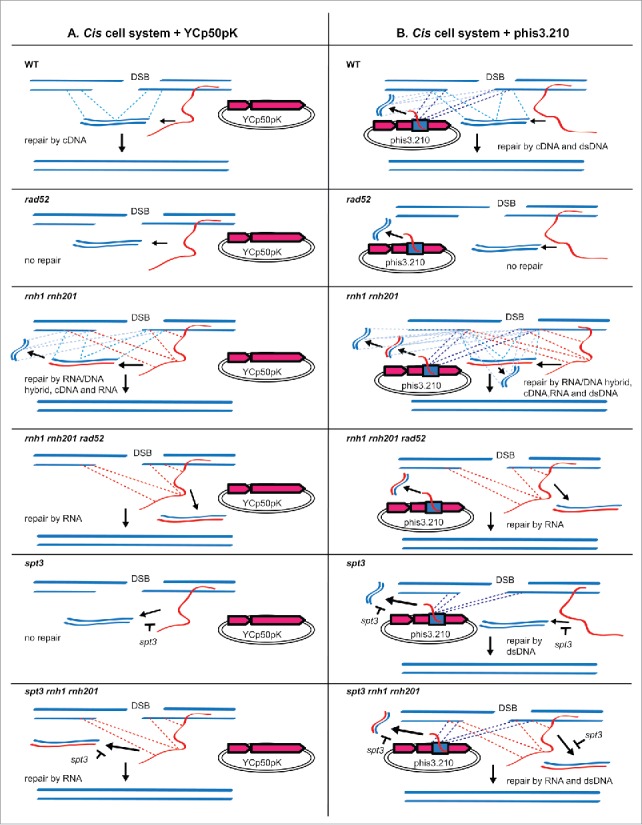

Our findings show that absence of RNase H1 and/or H2 activity in wild-type or null-spt3 cells results in increased frequency of His+ colonies after DSB induction not only in the cis but also in the trans system compared to wild-type RNase H cells.44 These results indicate that absence of RNase H function activates DSB repair by transcript RNA, and also stimulates DSB repair by cDNA. Following reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA, cDNA can be present as RNA-DNA hybrid, ssDNA, and/or dsDNA. Previously, we showed that DSB repair by ssDNA oligos was not increased in rnh1 rnh201 cells compared to RNase H wild-type cells.44 Moreover, our recent work indicates that defective RNase H2 alleles have higher level of cDNA in the form of RNA-cDNA hybrids.48 Here, we examined whether the RNase H defect is specific to stimulate DSB repair of the broken his3 locus via HR only by RNA and/or cDNA, or it can also stimulate DSB repair by gene conversion using as template for HR a truncated his3 copy carried on a dsDNA plasmid. We transformed wild-type, rad52, rnh1 rnh201, rnh1 rnh201 rad52, spt3 and spt3 rnh1 rnh201 strains of the cis system with a plasmid carrying an internal 210-bp segment of the HIS3 gene sequence (phis3.210) or with the control empty plasmid (YCp50pK) (Fig. 2B). To determine the frequency of His+ colonies following DSB induction at the his3 chromosomal locus for all these strains, we conducted the fluctuation assay of DSB repair. Depending on the genotype of the strains, cells containing the control vector YCp50pK can repair the DSB in the chromosomal his3 allele by using as template for HR the RNA, RNA/DNA hybrid and/or cDNA derived from the chromosomal his3 locus, while cells containing phis3.210, in addition to the RNA, RNA/DNA hybrid and/or cDNA derived from the chromosomal his3 locus, can also repair the DSB in his3 by using as template the DNA of the truncated his3 allele carried on phis3.210 cDNA, and/or potentially the RNA, RNA/DNA hybrid and/or cDNA derived from the transcription of this his3 plasmid allele (Table 2 and Fig. 4). In wild-type cells, there is a factor of 50 increase in the His+ frequency in the presence of phis3.210 compared to YCp50pK (Table 2). As expected, upon deletion of the RAD52 gene, which is required for any mechanism of DNA-DNA HR in yeast,49 no His+ colonies are detected with either plasmid. In rnh1 rnh201 cells carrying YCp50pK, the His+ frequency is more than a factor of 20 higher than in wild-type cells, due to elevated repair by cDNA and RNA, in agreement with our previous findings.44,48 The rnh1 rnh201 mutations in cells carrying phis3.210 result in less than 2-fold increase of the His+ frequency compared to wild-type cells carrying the same plasmid (Table 2). Such increase can be explained by the fact that in this background the DSB can be repaired not only by the truncated his3 on the plasmid, but also by RNA and cDNA derived from the chromosomal his3 copy, as well as by cDNA derived from the his3 allele on phis3.210. There could also be some repair in trans by the RNA derived from the his3 allele on phis3.210, although we expect this to be minimal compared to repair by cDNA. However, clearly, defects in RNase H1 and H2 do not stimulate DSB repair by the DNA of the his3 copy on the plasmid. In fact, in spt3 mutant cells, in which there is no or very little cDNA, there is no difference in the frequency of His+ colonies between spt3 and spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells carrying phis3.210 (Tables 2 and 3). While there could be some repair in trans by the RNA derived from the his3 allele on phis3.210 in spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells, we expect this to be minimal as shown in Keskin et al. 201444..44 Differently, there is a remarkable difference (more than a factor of 60,000) in the frequency of His+ colonies between spt3 and spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells carrying YCp50pK due to repair by RNA. Deletion of RAD52 in rnh1 rnh201 cells prevents repair by the his3 copy on the plasmid and by cDNA, while, as previously shown,44 it reduces, but not abolishes RNA repair either in the presence of phis3.210 or YCp50pK (Table 2). Overall, these results demonstrate that absence of RNase H activity does not stimulate DSB repair via DNA-DNA HR, while it strongly activates RNA-DNA HR, and HR between DNA and cDNA, in which the cDNA is most likely an RNA-DNA hybrid.

Table 2.

Effect of RNase H1 and H2-null mutations on DSB repair frequency by homologous cDNA, RNA/DNA hybrid, RNA and/or plasmid dsDNA.

| Genotype of cis system | His+ freq. | Survival | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT + YCp50pK | 2,500 | (2,300–2,830) | 1.9% |

| WT + phis3.210 | 133,000 | (104,000–151,000) | 2% |

| rad52 + YCp50pK | <0.1 | (0–0) | 0.2% |

| rad52 + phis3.210 | <0.1 | (0–0) | 0.16% |

| rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK | 52,300 | (47,700–63,300) | 1.4% |

| rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 | 248,000 | (226,000–309,000) | 1.2% |

| rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + YCp50pK | 930 | (790–1,300) | 0.07% |

| rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + phis3.210 | 1,000 | (590–1,200) | 0.08% |

| spt3 + YCp50pK | <0.1 | (0–0) | 7% |

| spt3 + phis3.210 | 134,000 | (96,000–180,000) | 4% |

| spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK | 6,300 | (5,900–7,200) | 10% |

| spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 | 99,000 | (92,000–119,000) | 7% |

Frequencies of His+ colonies per 107 viable cells for yeast strains of the cis system of the indicated genotypes and containing the indicated plasmid, following 48 h of galactose treatment are shown as median and 95% CI (in parentheses). Percentage of cell survival after incubation on galactose is also shown. There were 6–12 repeats for each strain. The significance of comparisons between different strains of the system was calculated using the Mann-Whitney U-test and it is shown in Table 3B. Fig. 4 serves as graphical guide for all results presented in this table.

Figure 4.

Templates for DSB repair in his3 locus to generate a functional HIS3 gene in cis system. This figure reflects the results of Table 2. Only repair mechanisms resulting in functional restoration of HIS3 are shown. DSB repair in his3 may also proceed by canonical NHEJ or HR with sister chromatid but does not result in functional HIS3. Regions of homology to the DSB site in his3 are shown as dashed lines. The spt3-null mutation results in inhibition of reverse transcription by Ty retroelements. Relevant genotypes are shown in the top left corner of each panel. Donor molecules that can serve as template for DSB repair are shown as solid blue lines, for cDNA and dsDNA, red and blue lines for RNA/DNA hybrid, and red lines for transcript-RNA. A) Repair of a DSB in cis system in the presence of YCp50pK. B) Repair of a DSB in cis system in the presence of phis3.210, which contains 210 bp of HIS3 (blue rectangle). DSB repair in trans templated by the RNA from the transcription of his3 on phis3.210 is also possible in cells containing rnh1 rnh201 mutations. Due to inefficient DSB repair by RNA in trans, we did not show the dashed lines for this template in the panels.

Table 3.

Statistical analysis (P-values) of the data.

| A | |

|---|---|

| Genotype of cis system |

P-value |

| WT + BDG283 vs. WT + BDG998 | < 0.0001 |

| WT + BDG283 vs. spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + BDG283 | < 0.0001 |

| WT + BDG998 vs. spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + BDG998 | < 0.0001 |

|

spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + BDG283 vs. spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + BDG998 |

0.4356 |

| B |

|

| WT + YCp50pK vs. WT + phis3.210 | < 0.0001 |

| WT + YCp50pK vs. rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK | < 0.0001 |

| WT + YCp50pK vs. spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK | < 0.0001 |

| WT + YCp50pK vs. rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + YCp50pK | < 0.0001 |

| WT + phis3.210 vs. spt3 + phis3.210 | 0.5425 |

| WT + phis3.210 vs. rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 | < 0.0001 |

| WT + phis3.210 vs. spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 | 0.1938 |

| WT + phis3.210 vs. rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + phis3.210 | 0.0001 |

| rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK vs. rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 | < 0.0001 |

| rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK vs. spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK | < 0.0001 |

| rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK vs. rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + YCp50pK | < 0.0001 |

| rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 vs. spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 | < 0.0001 |

| rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 vs. rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + phis3.210 | 0.0001 |

| spt3 + phis3.210 vs. rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 | 0.0012 |

| spt3 + phis3.210 vs. rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + phis3.210 | 0.0004 |

| spt3 + phis3.210 vs. rnh1 rnh201 spt3 + phis3.210 | 0.0830 |

| spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + YCp50pK vs. rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + YCp50pK | < 0.0001 |

| spt3 rnh1 rnh201 + phis3.210 vs. rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + phis3.210 | 0.0001 |

| rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + YCp50pK vs. rnh1 rnh201 rad52 + phis3.210 | 0.4990 |

Mann-Whitney U-test was applied to determine whether a statistical significant difference exists between pairs of gene correction frequencies obtained in DSB repair assays. A, Comparison of frequencies presented in Table 1. Two groups in a pair were considered to be significantly different when adjusted P-values were less than 0.05. B, Comparison of frequencies presented in Table 2. Two groups in a pair were considered to be significantly different when adjusted P-values were less than 0.05.

What's next?

Our recent findings raise a multitude of unanswered questions. We have shown that a transcript RNA can facilitate the repair of a DSB via a direct or indirect cDNA intermediate pathway. What are the players involved in this newly discovered mechanism of DNA repair? What factors mediate the increasing amount of repair in cis versus trans in spt3 rnh1 rnh201 cells? Based on the localization of the transcript, nearby its DNA gene, the cis system is more prone to the generation of an RNA-DNA hybrid at the his3 locus. If so, can reverse transcriptase enter the nucleus and facilitate reverse transcription at the site of a DSB? Can other polymerases use RNA as a template in DSB repair in vivo? What is the real efficiency of transcript-templated DNA repair? Our assay is limited by the detection of a phenotype, His+ cells, which originate only if the RNA template repairs the DSB after splicing of the artificial intron. If transcript RNA mediates DSB repair before splicing, there is no phenotype detected in our assay. Therefore, it is quite possible that we are underestimating the frequency of DSB repair by template transcript RNA. Does DSB repair by template transcript RNA occur in mammalian cells and in other cell types? We showed that transcript RNA-templated DNA repair occurs in dividing yeast cells. Can RNA template DSB repair in non-dividing cells? For example, highly transcribed genes in non-dividing cells, in which no sister chromatid is available, could be vulnerable; thus, these genes could be liable to RNA-templated DNA repair.

Our results of RNA repairing a DSB indirectly, via cDNA, shed light on the possibility of any RNA molecule being a target for reverse transcription by endogenous retrotransposon activity. If so, what factors mediate this reverse transcription? How abundant is the cDNA generation of endogenous RNA molecules? The Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome contains 5 classes of retroelements known as Tys, with Ty1 being the most abundant and well-studied. Is one class more prone to the generation of cDNA by endogenous RNA molecules? What can these factors tell us about other endogenous retroelements and retroviral infections? Retrotransposons are ubiquitous and plentiful in plant genomes, in some cases accounting for over 50% for the nuclear genome.50 Mammalian genomes are no strangers to retroelements with ˜3 million transposable elements in the human genome and 90% of those being retrotransposons.51 Given the copious amounts of retroelements found throughout various genomes and the relative abundant amounts of RNA in contrast to DNA, could RNA-templated DNA repair be playing a significant role in genome stability and modification?

Our work has provided fundamental preliminary data and resulted in the development of unique tools to study DNA repair via HR directly by RNA in the yeast model system. While inactivation of RNase H function allowed us to discover the capacity of cells to use transcript RNA in DSB repair, it is possible that RNA-DNA HR occurs also in RNase H wild-type cells. Mechanisms and functions of RNA-DNA HR are mostly unknown. Further studies are needed to illuminate the implications RNA-DNA HR may have on genome integrity.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains and plasmids

The background strain used to develop all strains used in this study is the haploid FRO-767 strain (leu2::HOcs, mataΔ::hisG, hoΔ, hmlΔ::ADE1, hmrΔ::ADE1, ade1, leu2–3,112, lys5, trp1::hisG, ura3–52, ade3::GAL::HO).44 BDG283 and BDG998 vectors (gifts from D. Garfinkel) were transformed into YS-291, 292 (WT) and YS-486, 487 (spt3 rnh1 rnh201) strains. BDG283 contains only pGAL1 and BDG998 contains the pGAL1-mhis3-AI cassette, and both plasmids are centromeric with the URA3 marker.4 YCp50pK and phis3.210 vectors are also centromeric with the URA3 marker. YCp50pK was constructed by cloning a SalI/EcoRI fragment with the kanMX4 gene from pFA6a-kanMX4 plasmid52 into the EcoRI/SalI sites of YCp50.53 To construct the phis3.210 vector, a 210-bp fragment of HIS3 was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using forward primer 5′-ACAGTGCTAAGT-AAGCTT-ATCTTCCCAGAAAAAGAGGC-3′ (HindIII site underlined) and reverse primer 5′-ATTGAGTTCCTA-AAGCTT-TACCACCGCTCTGGAAAGTG-3′(HindIII site underlined). The PCR product was digested with HindIII enzyme and was ligated into the YCp50pK vector, which was also digested with HindIII within the kanMX4 gene. The resulting plasmid was sequenced to confirm the correct 210-bp HIS3 insert. Both YCp50pK and phis3.210 were transformed into YS-291, 292 (WT), YS-444, 445 (rad52), YS-424, 426 (rnh1 rnh201), YS-490, 491 (rad52 rnh1 rnh201), YS-440, 441 (spt3), and YS-486, 487 (spt3 rnh1 rnh201) strains. Genetic methods and standard media were described previously.54

Fluctuation assay of DSB repair

All strains carrying a plasmid with the URA3 marker gene were maintained on Ura− medium. Fluctuation assays of DSB repair at the his3 locus were done as previously described.44 Briefly, yeast cells were grown in 50-ml lactose containing medium (YPLac), and incubated for 24 hours at 30°C. Next day, cells were counted and 107 or 108 cells were plated on galactose medium (YPGal) or SC-Ura−Gal medium. 104 cells were also plated on YPGal or SC-Ura−Gal medium to calculate survival. After 2 d incubation, cells were replica plated on His− or Ura−His− medium, and after 3 d His+ or Ura+His+ colonies were counted. Repair frequency and survival were calculated as previously described.44 Without galactose induction, no or rare His+ clones are obtained, as discussed in reference.44

Data presentation and statistics

Statistical analysis was calculated by using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Median and 95% confidence limits were expressed for each data sample. Statistical significance differences were calculated by using the nonparametric 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U-test, and all P-values of frequency comparisons are shown in Table 3.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Garfinkel for plasmids BDG283 and BDG998. This study was supported by US National Science Foundation award MCB-1021763, Georgia Research Alliance award number R9028, and National Institute of Health award GM115927 (to F.S.). H.K. was partly supported by a fellowship from the Ministry of Science of Turkey.

References

- 1.Baltimore D. Retroviruses and retrotransposons: the role of reverse transcription in shaping the eukaryotic genome. Cell 1985; 40:481-2; PMID:2578883; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autexier C, Lue NF. The structure and function of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Annu Rev Biochem 2006; 75:493-517; PMID:16756500; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luan DD, Korman MH, Jakubczak JL, Eickbush TH. Reverse transcription of R2Bm RNA is primed by a nick at the chromosomal target site: a mechanism for non-LTR retrotransposition. Cell 1993; 72:595-605; PMID:7679954; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90078-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derr LK, Strathern JN, Garfinkel DJ. RNA-mediated recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell 1991; 67:355-64; PMID:1655280; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90187-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curcio MJ, Garfinkel DJ. Single-step selection for Ty1 element retrotransposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991; 88:936-40; PMID:1846969; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.88.3.936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derr LK, Strathern JN. A role for reverse transcripts in gene conversion. Nature 1993; 361:170-3; PMID:8380627; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/361170a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore JK, Haber JE. Capture of retrotransposon DNA at the sites of chromosomal double-strand breaks. Nature 1996; 383:644-6; PMID:8857544; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/383644a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teng SC, Kim B, Gabriel A. Retrotransposon reverse-transcriptase-mediated repair of chromosomal breaks. Nature 1996; 383:641-4; PMID:8857543; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/383641a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melamed C, Nevo Y, Kupiec M. Involvement of cDNA in homologous recombination between Ty elements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 1992; 12:1613-20; PMID:1372387; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.12.4.1613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nevo-Caspi Y, Kupiec M. Transcriptional induction of Ty recombination in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994; 91:12711-5; PMID:7809107; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharon G, Burkett TJ, Garfinkel DJ. Efficient homologous recombination of Ty1 element cDNA when integration is blocked. Mol Cell Biol 1994; 14:6540-51; PMID:7523854; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.14.10.6540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nevo-Caspi Y, Kupiec M. cDNA-mediated Ty recombination can take place in the absence of plus-strand cDNA synthesis, but not in the absence of the integrase protein. Curr Genetics 1997; 32:32-40; PMID:9309168; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s002940050245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esnault C, Maestre J, Heidmann T. Human LINE retrotransposons generate processed pseudogenes. Nat Genet 2000; 24:363-7; PMID:10742098; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/74184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrish TA, Gilbert N, Myers JS, Vincent BJ, Stamato TD, Taccioli GE, Batzer MA, Moran JV. DNA repair mediated by endonuclease-independent LINE-1 retrotransposition. Nat Genet 2002; 31:159-65; PMID:12006980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrish TA, Garcia-Perez JL, Stamato TD, Taccioli GE, Sekiguchi J, Moran JV. Endonuclease-independent LINE-1 retrotransposition at mammalian telomeres. Nature 2007; 446:208-12; PMID:17344853; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Storici F. RNA-mediated DNA modifications and RNA-templated DNA repair. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2008; 10:224-30; PMID:18535929 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fink GR. Pseudogenes in yeast? Cell 1987; 49:5-6; PMID:3549000; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90746-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niu DK, Hou WR, Li SW. mRNA-mediated intron losses: evidence from extraordinarily large exons. Mol Biol Evol 2005; 22:1475-81; PMID:15788745; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/molbev/msi138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gargouri A. The reverse transcriptase encoded by ai1 intron is active in trans in the retro-deletion of yeast mitochondrial introns. FEMS Yeast Res 2005; 5:813-22; PMID:15925309; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.femsyr.2004.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murakami E, Feng JY, Lee H, Hanes J, Johnson KA, Anderson KS. Characterization of novel reverse transcriptase and other RNA-associated catalytic activities by human DNA polymerase gamma: importance in mitochondrial DNA replication. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:36403-9;PMID:12857740;http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M306236200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trott DA, Porter AC. Hypothesis: transcript-templated repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Bioessays 2006; 28:78-83; PMID:16369940; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.20339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diemer GS, Stedman KM. A novel virus genome discovered in an extreme environment suggests recombination between unrelated groups of RNA and DNA viruses. Biol Direct 2012; 7:13; PMID:22515485; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1745-6150-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krupovic M. Recombination between RNA viruses and plasmids might have played a central role in the origin and evolution of small DNA viruses. Bioessays 2012; 34:867-70; PMID:22886750; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.201200083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu PZ, Yuan S, Li Y, Zhang HY, Wang XD, Lin HH, Wu XJ. Genome-wide high-frequency non-Mendelian loss of heterozygosity in rice. Genome 2007; 50:297-302; PMID:17502903; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1139/G07-005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suberbielle E, Sanchez PE, Kravitz AV, Wang X, Ho K, Eilertson K, Devidze N, Kreitzer AC, Mucke L. Physiologic brain activity causes DNA double-strand breaks in neurons, with exacerbation by amyloid-β. Nat Neurosci 2013; 16:613-21; PMID:23525040; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehler MF. Epigenetics and the nervous system. Ann Neurol 2008; 64:602-17; PMID:19107999; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ana.21595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mattick JS, Mehler MF. RNA editing, DNA recoding and the evolution of human cognition. Trends Neurosci 2008; 31:227-33; PMID:18395806; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bozas A, Beumer KJ, Trautman JK, Carroll D. Genetic analysis of zinc-finger nuclease-induced gene targeting in Drosophila. Genetics 2009; 182:641-51; PMID:19380480; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.109.101329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onozawa M, Zhang Z, Kim YJ, Goldberg L, Varga T, Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM, Aplan PD. Repair of DNA double-strand breaks by templated nucleotide sequence insertions derived from distant regions of the genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111(21):7729-34; PMID:24821809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aida T, Chiyo K, Usami T, Ishikubo H, Imahashi R, Wada Y, Tanaka KF, Sakuma T, Yamamoto T, Tanaka K. Cloning-free CRISPR/Cas system facilitates functional cassette knock-in in mice. Genome Biol 2015; 16:87; PMID:25924609; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/s13059-015-0653-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storici F, Bebenek K, Kunkel TA, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. RNA-templated DNA repair. Nature 2007; 447:338-41; PMID:17429354; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature05720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen Y, Storici F. Generation of RNA/DNA Hybrids in Genomic DNA by Transformation using RNA-containing Oligonucleotides. J Vis Exp 2010; 45 pii:2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen Y, Storici F. Detection of RNA-templated double-strand break repair in yeast. Methods Mol Biol 2011; 745:193-204; PMID:21660696; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-61779-129-1_12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thaler DS, Tombline G, Zahn K. Short-patch reverse transcription in Escherichia coli. Genetics 1995; 140:909-15; PMID:7545627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen Y, Nandi P, Taylor MB, Stuckey S, Bhadsavle HP, Weiss B, Storici F. RNA-driven genetic changes in bacteria and in human cells. Mutat Res 2011; 717:91-8; PMID:21515292; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angeleska A, Jonoska N, Saito M, Landweber LF. RNA-guided DNA assembly. J Theor Biol 2007; 248:706-20; PMID:17669433; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nowacki M, Vijayan V, Zhou Y, Schotanus K, Doak TG, Landweber LF. RNA-mediated epigenetic programming of a genome-rearrangement pathway. Nature 2008; 451:153-8; PMID:18046331; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature06452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fang W, Landweber LF. RNA-mediated genome rearrangement: hypotheses and evidence. Bioessays 2013; 35:84-7; PMID:23281134; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.201200140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kirkpatrick DP, Radding CM. RecA protein promotes rapid RNA-DNA hybridization in heterogeneous RNA mixtures. Nucleic Acids Res 1992; 20:4347-53; PMID:1508725; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/20.16.4347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirkpatrick DP, Rao BJ, Radding CM. RNA-DNA hybridization promoted by E. coli RecA protein. Nucleic Acids Res 1992; 20:4339-46; PMID:1380698; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/20.16.4339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kasahara M, Clikeman JA, Bates DB, Kogoma T. RecA protein-dependent R-loop formation in vitro. Genes Dev 2000; 14:360-5; PMID:10673507; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.14.3.360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaitsev EN, Kowalczykowski SC. A novel pairing process promoted by Escherichia coli RecA protein: inverse DNA and RNA strand exchange. Genes Dev 2000; 14:740-9; PMID:10733533; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.14.6.740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wahba L, Gore SK, Koshland D. The homologous recombination machinery modulates the formation of RNA-DNA hybrids and associated chromosome instability. Elife 2013; 2:e00505; PMID:23795288; http://dx.doi.org/25186730 10.7554/eLife.00505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keskin H, Shen Y, Huang F, Patel M, Yang T, Ashley K, Mazin AV, Storici F. Transcript-RNA-templated DNA recombination and repair. Nature 2014; 515:436-9; PMID:25186730; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature13682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hani J, Feldmann H. tRNA genes and retroelements in the yeast genome. Nucleic Acids Res 1998; 26:689-96; PMID:9443958http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/26.3.689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boeke JD, Styles CA, Fink GR. Saccharomyces cerevisiae SPT3 gene is required for transposition and transpositional recombination of chromosomal Ty elements. Mol Cell Biol 1986; 6:3575-81; PMID:3025601; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.6.11.3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cerritelli SM, Crouch RJ. Ribonuclease H: the enzymes in eukaryotes. FEBS J 2009; 276:1494-505; PMID:19228196; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06908.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keskin H, Storici F. Defects in RNase H2 Stimulate DNA Break Repair by RNA Reverse Transcribed into cDNA. Microrna 2015; 4:109-16; PMID:26456534; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/2211536604666150820120129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Symington LS, Rothstein R, Lisby M. Mechanisms and regulation of mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 2014; 198:795-835; PMID:25381364; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.114.166140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumar A, Bennetzen JL. Plant retrotransposons. Annu Rev Genet 1999; 33:479-532; PMID:10690416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bannert N, Kurth R. Retroelements and the human genome: new perspectives on an old relation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101 Suppl 2:14572-9; PMID:15310846;http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0404838101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Delneri D, Gardner DC, Bruschi CV, Oliver SG. Disruption of seven hypothetical aryl alcohol dehydrogenase genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and construction of a multiple knock-out strain. Yeast 1999; 15:1681-9; PMID:10572264; http://dx.doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rose MD, Novick P, Thomas JH, Botstein D, Fink GR. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae genomic plasmid bank based on a centromere-containing shuttle vector. Gene 1987; 60, 237-43; PMID:3327750; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90232-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Storici F, Durham CL, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. Chromosomal site-specific double-strand breaks are efficiently targeted for repair by oligonucleotides in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003; 100:14994-9; PMID:14630945; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.2036296100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]