Abstract

The canonical activity of glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS) is to charge glycine onto its cognate tRNAs. However, outside translation, GARS also participates in many other functions. A single gene encodes both the cytosolic and mitochondrial forms of GARS but 2 mRNA isoforms were identified. Using immunolocalization assays, in vitro translation assays and bicistronic constructs we provide experimental evidence that one of these mRNAs tightly controls expression and localization of human GARS. An intricate regulatory domain was found in its 5′-UTR which displays a functional Internal Ribosome Entry Site and an upstream Open Reading Frame. Together, these elements hinder the synthesis of the mitochondrial GARS and target the translation of the cytosolic enzyme to ER-bound ribosomes. This finding reveals a complex picture of GARS translation and localization in mammals. In this context, we discuss how human GARS expression could influence its moonlighting activities and its involvement in diseases.

Keywords: aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, IRES, post-transcriptional control, uORF

Abbreviations

- aaRS

aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase

- ER

Endoplasmic Reticulum

- GARS

Glycyl-tRNA Synthetase

- IRES

Internal Ribosome Entry Site

- MTS

Mitochondrial Targeting Signal

- Uorf

upstream Open Reading Frame

- UTR

UnTranslated Region

Introduction

Human glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS) is an essential component of the translation apparatus. GARS is ubiquitously expressed and plays a central role in protein synthesis by catalyzing the attachment of glycine to cognate tRNAs (tRNAs). However, GARS, like other mammalian aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRS) 1-3 is involved in functions beyond translation.4 Most of these alternative functions were identified mainly through the discovery of several diseases linked to mutations in the corresponding gene or to the presence of antibodies against extracellular GARS. In humans, at least 13 dominant mutations in the GARS gene cause motor and sensory axon loss in the peripheral nervous system and lead to clinical phenotypes ranging from Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) type 2D neuropathy to a severe infantile form of spinal muscular atrophy type V.5-10 Though GARS activity is required in all cells, the CMT-associated mutations affect only the peripheral nervous system. The links between GARS mutations, tissue-specificity, and pathological mechanisms remain unclear (reviewed in).7 Several studies identified autoantibodies to 8 different aaRSs; among them, anti-GARS antibodies (anti-EJ) are mainly found in patients with inflammatory myopathy, polymyositis and dermatomyositis (reviewed in).11 Yet information on their clinical impact is still limited. Interestingly, GARS autoantibodies were also detected in the sera of patients with breast cancer.12 GARS is indeed secreted by macrophages and acts as a cytokine with a distinct role against specific tumor cells.13 Moreover, GARS binds the Internal Ribosome Entry Site (IRES) located at the 5′-end of the poliovirus RNA genome and promotes its cap-independent translation initiation.14 Together these observations suggest that, in mammals, GARS expression may be regulated in response to many different stimuli.

Three independent reports indicated that a single gene encodes both the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial forms of human GARS.15-17 This is in contrast to other aaRSs for which cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNA aminoacylation is achieved by the products of 2 separate genes (the only other exception being lysyl-tRNA synthetase). The GARS gene was predicted to produce both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial enzymes via alternative translational start sites.15 Analysis of fetal liver cDNA encoding human GARS,16 as well as primer extension experiments on transfected cells.17 identified a single mRNA characterized by a long 5′-UTR with 5 putative initiation codons (Fig. 1A). Based on these observations, it was anticipated that the more distal start codons relative to the transcriptional start site would initiate translation of the cytosolic GARS, while one or more proximal codons would initiate the mitochondrial enzyme. In addition, the presence of 3 other upstream initiation codons could indicate the existence of some regulatory mechanism(s); for instance one of these codons would lead to the synthesis of a short upstream Open Reading Frame (uORF), encoding 47 amino acids and potentially controlling GARS expression.16

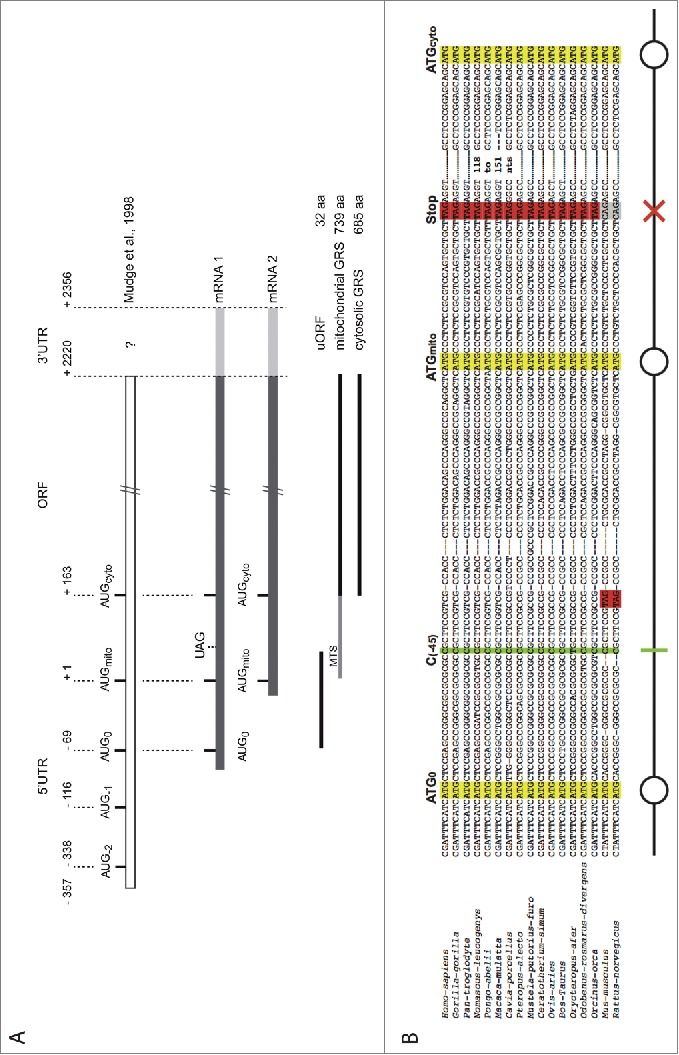

Figure 1.

Organization of human GARS mRNAs. (A). Schematic representation of the 2 isoforms of the human GARS mRNA revealed in this study. The sequence identified by Mudge and collaborators in 1998 in fetal liver cells17 was used as a reference. The long mRNA1 contains 3 initiation codons, AUG0 (initiates the synthesis of the uORF), AUGmito (initiates translation of the mitochondrial targeting signal -MTS- fused to GARS), AUGcyto (initiates translation of the cytosolic GARS) and a UAG stop codon (ends translation of the uORF). The shorter mRNA2 contains only AUGmito and AUGcyto. (B). Multiple alignment of mammalian mRNA1 5′-UTR: blasting the nucleotide sequence of Homo sapiens GARS mRNA1 (NC_018918.2) against all NCBI nucleotide databases (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast) retrieved 43 sequences only from other mammalian genomes. Among them, 14 GARS sequences were from primates. Here, is shown only a representative selection of the retrieved sequences: Homo-sapiens (NC_018918.2), Gorilla-gorilla (NC_018431.1), Pan-troglodyte (NC_006474.3), Nomascus-leucogenys (NC_019832.1), Pongo-abelii (NC_012598.1), Macaca-mulatta (NC_007860.1), Cavia-porcellus (XM_003467957.2), Pteropus-alecto (XM_006912040.1), Mustela-putorius-furo (XM_004762573.1), Ceratotherium-simum (XM_004418866.1), Ovis-aries (XM_004007927.1), Bos-Taurus (NM_001097566.1), Orycteropus-afer (XM_007945456.1), Odobenus-rosmarus-divergens (XM_004413949.1), Orcinus-orca (XM_004269943.1), Mus-musculus (NC_000072.6), Rattus-norvegicus (NC_005103.3) GARS sequences. Sequence alignments were computed with Tcoffee software (http://igs-server.cnrs-mrs.fr/Tcoffee/tcoffee_cgi/index.cgi).46 The 3 AUG codons, AUG0, AUGmito and AUGcyto, are boxed in yellow, the stop codon in red. Absence of these specific codons is indicated in gray on the alignment. The schematic representation of the 5′- end of mRNA1, used in this manuscript, is indicated: AUGs are signaled with circles, the uORF stop codon with a red cross, and the frameshift deletion with a green bar.

This study focuses on the control of human GARS expression. Indeed, many aspects of the regulation of this enzyme remain unclear, especially its tissue specific expression and the control of both mitochondrial and cytosolic forms of the enzyme. Therefore, in this study, different human tissues were used to further characterize the 5'-UTR of the human GARS mRNA that may lead to the understanding of the molecular mechanism governing such regulations. Contrary to previous studies, which identified one long mRNA with 5 start codons, 2 different mRNA isoforms containing 2 and 3 start codons respectively were found. These two GARS mRNAs were present in all tissues and vary only by the length of their 5′-UTRs. They were tested for their respective capacity to support translation of the mitochondrial and the cytosolic GARS, in vitro and in transfected cells. Interestingly, both 5′-UTRs behave differently. The longer 5′-UTR contains not only an uORF but also a functional IRES, which directs GARS translation into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), strengthening our prediction of a complex regulatory mechanism.

Results

Identification of 2 mRNA isoforms

Both the human mitochondrial and cytosolic glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS) enzymes are encoded by the same gene (GARS), located on chromosome 7, and use 2 alternative initiation codons. One mRNA isoform was previously identified from fetal liver cDNA, showing the presence of a long 5′-UTR (357 nucleotides upstream of the putative initiator codon for mitochondrial GARS synthesis) containing 3 other potential initiation codons.17 (Fig. 1A). To further explore the presence of alternative mRNA isoforms in other human tissues, 5′- and 3′-RLM-RACE PCR (RNA Ligase Mediated Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends PCR, Fig. S1A) were performed on total RNA from 6 different human tissues: liver, brain, spinal cord, muscle, heart and spleen. Two populations of mRNAs (mRNA1 and mRNA2) were present in brain, spinal cord, muscle, heart and spleen tissues and only one (mRNA2) was found in liver tissue (Fig. S1B). These two mRNA isoforms contain both initiator codons corresponding to the predicted translation start sites of the mitochondrial GARS (AUGmito, at position +1) and of the cytosolic GARS (AUGcyto, at position +163). mRNA1 and mRNA2 shared the same 3′-UTR sequence (166 nts; data not shown) and differ only in the length of their 5′-UTR (Fig. 1A). The longest mRNA (mRNA1) was characterized by an 85 nt long 5′-UTR (+/- 6 nts) and contains one extra AUG initiation codon (AUG0) close to the 5′-end (position -69). Unlike AUGmito and AUGcyto, AUG0 was not in frame with the GARS ORF and codes for a small uORF. This uORF would potentially initiate the synthesis of a 32 amino acid peptide that ends at a stop codon (UAG) located 26 nt downstream of AUGmito. The shorter mRNA, mRNA2, had a very short 5′-UTR (between 21 and 29 nt) and displayed only AUGmito and AUGcyto start codons (Fig. 1A).

5′-RLM-RACE PCR was done again, under the same conditions, but without removing the 5′-cap from the mRNAs before ligation of the 5′-adaptor (Fig. S1A). No PCR fragments were retrieved, indicating that both GARS mRNA1 and mRNA2 are capped in the cell.

Searching for mRNA1 and mRNA2 in the DataBase of Transcriptional Start Sites.18 (DBTSS, which represents exact positions of TSSs in the genome) 2 TSSs corresponding to both GARS mRNA isoforms were found. Based on the number of reads for each mRNA, relative expressions of mRNA1 and mRNA2 could be determined. They vary considerably in the different tissues tested (Fig. S2), with in general, more mRNA2 than mRNA1. Only adult testis, lung and brain 1 show more mRNA1 than mRNA2.

Sequence comparison

The 5′-end of the GARS mRNA1 sequence was used to blast NCBI nucleotide databases. Forty-three sequences were retrieved, showing that this organization, with 3 ATG codons and one stop codon, was found only among mammals (Fig. 1B). However, in the case of the mouse and rat genomes, the GARS DNA sequences differ by the position of the stop codon, found before AUGmito. There are a few other exceptions in the translation potential of some sequences (not shown on the alignment): pika (Ochotona princeps), wild boar (Sus scrofa), elephant (Loxodonta Africana) and dog (Canis lupus familiaris) have the AUG0 in the same open reading frame as AUGmito and AUGcyto and the dolphin (Lipotes vexillifer) sequence is missing AUG0, suggesting different regulatory mechanisms or hypothetical sequencing mistakes. Besides mammals, other eukaryotic GARS gene sequences did not align with the 250 nts found at the 5′-end of the GARS mRNA1 sequence.

Characterization of mRNA1 and mRNA2 in translation

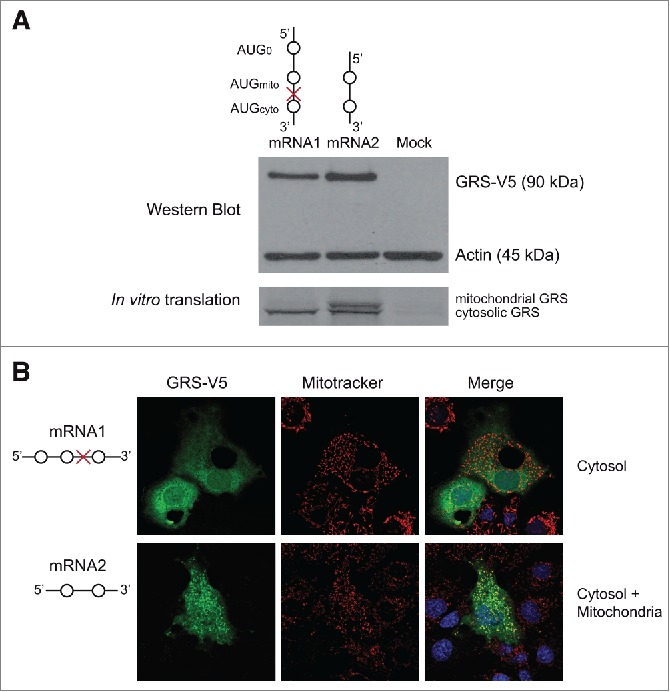

DNA constructs encoding mRNA1 and mRNA2 sequences fused to the V5-tag were transfected in COS-7 cells. In order to compare the capacity of each mRNA isoform to support GARS expression and determine its nature (mitochondrial or cytosolic), Western blot and immunolocalization experiments were performed on transfected cells (Fig. 2). Western blot analysis (Fig. 2A) showed that both mRNAs produced a unique band corresponding to the theoretical size of the cytosolic GARS (approximately 90 kDa). Because the mitochondrial targeting signal (MTS) (54 amino acids, 5.6 kDa) is removed when the mitochondrial GARS enzyme is targeted to its final destination, the resulting mature enzyme cannot be differentiated from the cytosolic GARS based only on its size. Thus, mRNA1 and mRNA2 were tested in vitro in wheat germ extract translation assays (Fig. 2A). In this system, proteins are not matured, thus it is possible to distinguish the mitochondrial from the cytosolic GARS based on their respective lengths. Indeed, in the test performed with mRNA2, both the mitochondrial (long) and the cytosolic (short) GARSs could be detected. However, mRNA1 led only to the synthesis of the cytosolic (short) GARS. Immunolocalization experiments (Fig. 2B) allowed us to further characterize the products of translation of the 2 mRNAs. In agreement with the results of in vitro translation experiments, GARS-V5 subcellular localizations showed that the mRNA2 construct leads to the synthesis of both the mitochondrial and the cytosolic GARSs. Since the 5′UTR sequences are continuous in the genome, it indicates that both AUGmito and AUGcyto codons present in this mRNA are used to initiate efficient translation. However, the longer mRNA1, which contains 3 potential initiation sites, codes for the cytosolic form of the protein only.

Figure 2.

Translation of both mRNA isoforms in vivo and in vitro. (A). Top panel shows Western blot analysis of COS-7 cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 encoding mRNA1 or mRNA2 fused to a V5 epitope nucleotide sequence on their 3′-ends. Translated GARS-V5 proteins are detected by anti-V5 antibodies. Detection of the 42 kDa ß-actin (anti-actin antibodies) was included as a loading control. Bottom panel corresponds to translation of radioactive GARSs from mRNA1 and mRNA2 in vitro, accomplished using wheat germ extracts. (B). GARS-V5 was detected by immunofluorescence, using anti-V5 antibodies coupled to FITC (green). Mitochondria were stained with Mitotracker Orange CMTMRos (red) and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The final localization of GARS is specified for each mRNA. For the mRNA1 scheme, please refer to the end of the Figure 1 legend.

Functional characterization of the 3 AUG codons present in mRNA1

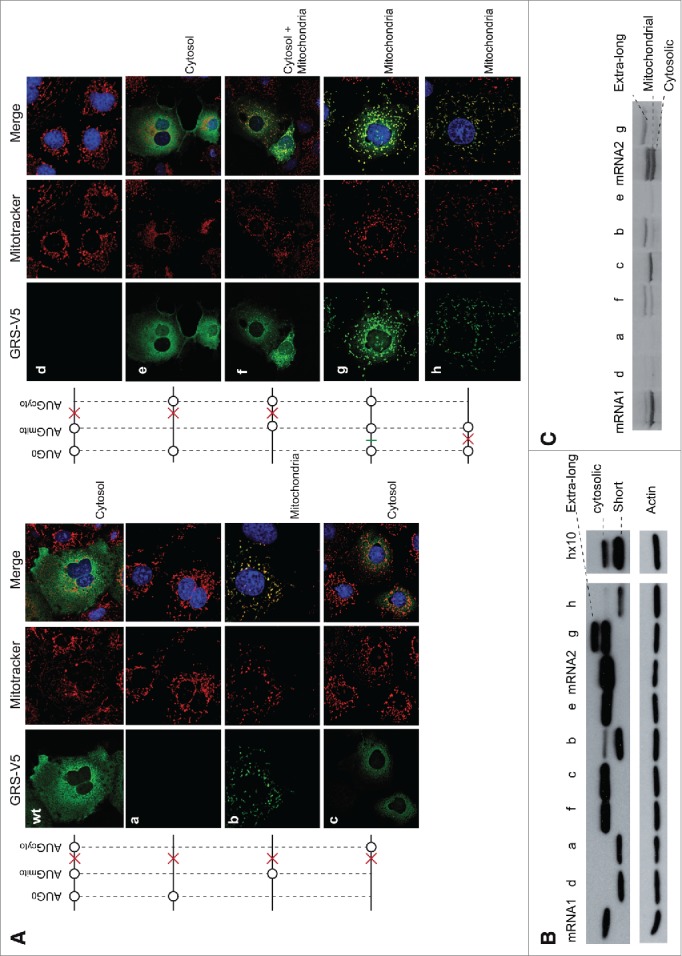

In order to assess if all 3 AUG codons in mRNA1 can initiate translation, they were mutated and tested. The translation efficiencies of GARS translated from these mRNA1 variants were determined by Western blot analysis and their subcellular localizations were determined by immunolocalization of transfected COS-7 cells (Fig. 3A, B; Fig. S3). In the absence of the 2 other AUG codons, initiation at AUG0 (mutant a) did not produce any visible protein, initiation at AUGmito (mutant b) led to the synthesis of the mitochondrial GARS and initiation at AUGcyto (mutant c) allowed the synthesis of the cytosolic GARS. Addition of AUG0 upstream of AUGmito (mutant d), prevented initiation at AUGmito; yet, AUG0 did not affect translation initiation at AUGcyto (mutant e). These observations indicated that AUG0 selectively prevents translation of the mitochondrial GARS consistently. Mutation of AUG0 (mutant f) restored translation initiation at AUGmito. Finally, the deletion of nt C at position -45 (Fig. 1B) allowed AUG0 to be in the same reading frame as AUGmito and AUGcyto (mutant g). Interestingly, this frame-shift allowed the synthesis of a GARS that was mainly targeted to the mitochondria, suggesting that in this mutant, either AUG0 or AUGmito might be used to initiate translation.

Figure 3.

Immunolocalization of GARS expressed from mutated mRNA1. (A). Six mutants (a to h) were generated in mRNA1 where the different AUG codons were tested for translation. GARS-V5, mitochondria and nuclei detection were performed as indicated in the legend of Figure 2 and the mRNA1 scheme is described at the end of the Figure 1 legend. The final localization of GARS is specified for each mRNA. Corresponding co-localization statistics are indicated in Figure S3A. (B). GARS expression levels (Western blot). Mutant g shows 2 bands (extra-long GARS and cytosolic GARS), indicating that the protein is only partially matured inside the mitochondria. In mutants a, b, d and h, all missing AUGcyto, initiation of a shorter GARS is observed, which is not detectable in immunolocalization experiments. This short form of the protein is observed only in vitro and appears when initiation is very inefficient. It shows (i) that the mRNA is present in the test and (ii) that the ribosome scans until it finds the next initiator codon. In the specific case of mutant h, its expression is so low that 10 times more protein extract was loaded in hx10 to detect it. Detection of the 42 kDa ß-actin (anti-actin antibodies) was included as a loading control. (C). The same mutants were used in in vitro translation experiments (rabbit reticulocyte extracts) in the presence of 35S methionine. Mutant h was not tested in vitro.

T7 RNA polymerase transcribed mRNA1 and mRNA2 as well as mRNA1 mutants (a to g) were tested for in vitro translation (Fig. 3C). The results confirmed what was observed with immunolocalization experiments: AUG0 alone or with AUGmito did not allow GARS expression (mutants a and d); removing AUG0 permitted ribosomes to initiate at AUGmito and AUGcyto (mutant f); and the presence of only AUGcyto (mutant c) or AUGmito (mutant b) led to the synthesis of the cytosolic or the mitochondrial GARS, respectively. Lastly, the frameshift mutation (mutant g) led to the synthesis of an “extra-long” GARS that corresponds to the addition of 23 extra amino acids at the N-terminus of the MTS, indicating that initiation takes place only at AUG0. This addition didn't affect the targeting sequence (Fig. 3A, mutant g). This result clearly shows that, despite its close proximity to the 5′-end of mRNA1 (3 to 20 nts, Fig. S1B), AUG0 is recognized as an initiation codon and would thus promote the synthesis of the 32-residue peptide.

Two main differences between in vivo immunolocalization and in vitro translation results occurred. The wild type mRNA1 product did not show any mitochondrial localization in Fig. 3A, however in vitro a weak band that corresponded to the mitochondrial GARS could be observed. The other difference concerned mutant e, which was strongly expressed in the cytosol in vivo but was a poor substrate in vitro. Artifacts, such as mRNA alternative structures, due to in vitro T7 RNA polymerase transcription, could explain these discrepancies. Moreover mutation of AUGmito might destabilize the structure of the 5′ end of the in vitro transcribed RNA, so that the alternative structure does not allow efficient translation initiation in vitro.

The ribosome reinitiates at the AUG immediately downstream of the uORF stop codon

In order to test the possibility that ribosomes reinitiate after synthesis of the uORF, the stop codon initially present between AUGmito and AUGcyto (mutant d) was moved before AUGmito (mutant h). Despite reduced efficiency, the mitochondrial GARS was translated instead of the cytosolic GARS as expected for ribosome reinitiation (Fig. 3A-C). Additionally, since construct g gives rise to only the extra-long GARS (Fig. 3B, C), it implies that all ribosomes initiate first at the AUG0 with no leaky scanning. It thus also supports that, in wild type mRNA1, AUGcyto is recognized only by reinitiating ribosomes that have translated the uORF.

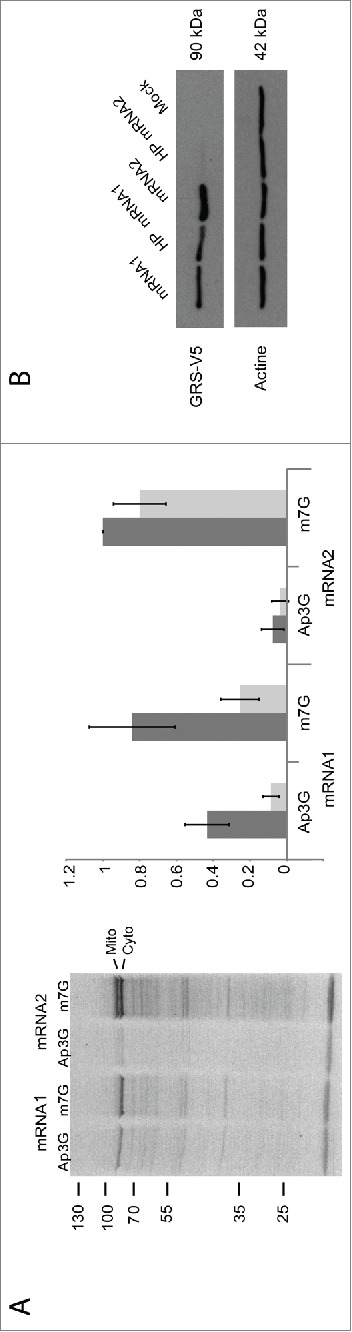

mRNA1 supports cap-independent translation initiation

Taking into account the high percentage of GC (74%) and our unsuccessful attempts to solve the mRNA1 structure in solution using chemical and enzymatic methods, it was considered that mRNA1 would encompass a stable fold. Together with its unique expression pattern, we hypothesized that the extra RNA sequence present at the 5′-end of mRNA1 would contain an IRES. In order to test this idea, mRNA1 and mRNA2, each 5′-modified either with the natural m7G cap or with the non-functional Ap3G cap analog were produced. These mRNA transcripts were subjected to in vitro translation in wheat germ extracts (Fig. 4A). As expected, translation of m7G capped mRNA1 generated one major band corresponding to the cytosolic GARS (about 80%) and translation of m7G-capped mRNA2 led to 2 bands of comparable intensities (55% cytosolic GARS and 45% mitochondrial GARS). In contrast, when these mRNAs were capped with the non-functional Ap3G cap analog, mRNA1 was still translated (>50%) while translation of mRNA2 was abolished.

Figure 4.

Cap-independent versus cap-dependent initiation. (A). In vitro translation reactions of mRNA1 and mRNA2 were performed with wheat germ extracts. Both mRNAs were capped either with the natural m7G or the inhibitor cap analog Ap3G. Synthesized GARSs correspond to the mitochondrial (upper band) and cytosolic (lower band) enzymes. Expression levels of cytosolic (dark bars) and mitochondrial (light bars) GARSs were quantified relative to the cytosolic GARS translated from mRNA2. Error bars were calculated from 3 independent experiments. (B). Western blot analysis: Effect of a strong hairpin structure on GARS expression: COS-7 cells were transfected with pCDNA3.1 constructs containing a strong hairpin structure introduced at the 5′-end of mRNA1 and mRNA2 (HP mRNA1 and HP mRNA2, respectively).

To further confirm the ability of mRNA1 to initiate translation in a cap-independent manner, a stable hairpin structure.19 was inserted at the 5′-extremity of both mRNA1 and mRNA2 constructs. Such a structure is expected to hinder ribosome scanning and, as a consequence, cap-dependent initiation.20,21 mRNAs without or with the stable hairpin structure were expressed for 24 hours in COS-7 cells. The corresponding Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B) clearly shows that the hairpin structure indeed inhibited mRNA2 but not mRNA1 translation confirming the presence of a peculiar initiation site in mRNA1.

mRNA1 contains a functional IRES

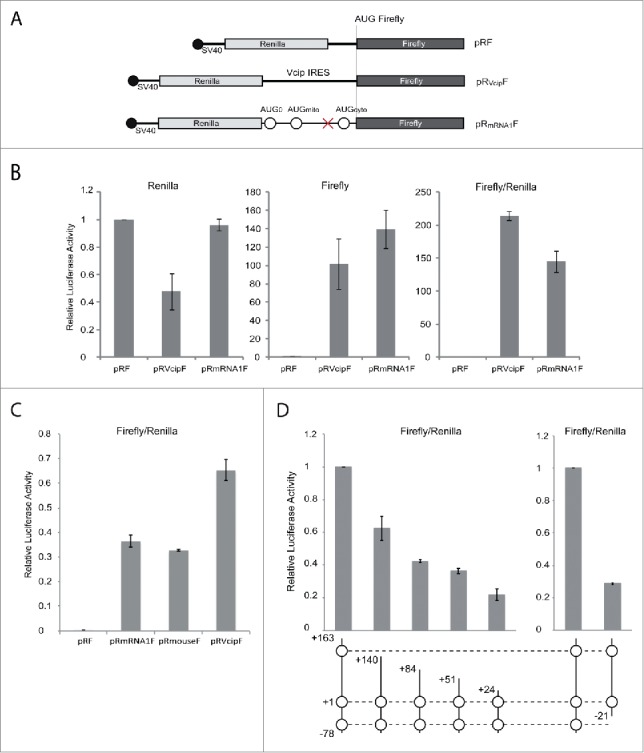

To test the presence of a functional IRES in mRNA1, the bicistronic renilla/firefly luciferase system pRF was used. The pRF vector contains an SV40 promoter and generates long mRNAs with 2 consecutive cistrons: the first one is translated in a cap-dependent manner and codes for the renilla luciferase (R), whereas the second one codes for the firefly luciferase (F), which is expressed only if the inserted intercistronic region has a functional IRES.20

Vectors pRF and pRVcipF (containing a well-characterized cellular IRES).22 were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. The entirety of mRNA1 (nt -78 to +163, including AUG0, AUGmito and AUGcyto) was cloned in the intercistronic region (Fig. 5A). COS-7 cells were then transiently transfected with the 3 constructs and both renilla and firefly luciferase activities were measured (Fig. 5B). The relative firefly/renilla ratio showed strong IRES activity for pRmRNA1F, 150-fold higher than the negative control and comparable to pRVcipF IRES activity (70%).

Figure 5.

Comparison of mRNA1 and Vcip IRES elements for their ability to initiate translation. (A). Schematic representation of biscistronic pRF constructs: sequences corresponding to the Vcip IRES and mRNA1 5′-end (containing the 3 AUG codons) were inserted in the intercistronic region between the renilla and firefly ORFs (pRVcipF and pRmRNA1F). The cap structure at the 5′-end of the bicistronic mRNA is indicated with a black circle. (B). pRF, pRVcipF and pRmRNA1F were transfected in COS-7 cells and renilla (cap dependent initiation) and firefly (IRES-mediated initiation) luciferase activities were measured. pRVcipF and pRmRNA1F luciferase activities were represented relative to pRF activity. (C). pRF, pRmRNA1F, pRmouseF and pRVcipF were transfected in COS-7 cells and IRES-mediated initiation were measured. pRmouseF express the mouse sequence corresponding to mRNA1 (see Fig. 1B). (D). Shorter versions of the mRNA1 IRES sequence were cloned in pRF and their respective luciferase activities were measured. Graphic representations of pRmRNA1F, pR mRNA1F deletants and pRmRNA2F activities are relative to the pRF negative control. Standard deviations were calculated from 3 independent experiments. For the mRNA1 scheme, please refer to the end of the Figure 1 legend.

Several controls were carried out to exclude any experimental artifacts (Fig. S4). To rule out the presence of cryptic promoters, the SV40 promoter was deleted from the bicistronic vectors, hindering the transcription of bicistronic mRNAs. As expected, both renilla and firefly activities were drastically decreased confirming the absence of strong cryptic promoters (Fig. S4A). However, for both pRVcipF and pRmRNA1F, a residual firefly luciferase activity (20% and 15%, respectively) could still be detected, corresponding to the cryptic promoter activity present in the firefly liciferase gene.23

Because unwanted splicing could lead to the production of 2 monocystronic mRNAs instead of the bicistronic mRNA, the synthesis of the firefly luciferase could be the result of a cap-dependent initiation. Thus, the presence of such putative splicing events was tested: total RNAs, purified from transfected COS-7 cells, were subjected to reverse transcription and PCR amplification. Specific primers covering the promoter region and part of the firefly luciferase sequence were used (Fig. S4B). The results of this specific RT-PCR reaction showed that a unique product was amplified corresponding to each pRF construct (the size of amplified inserts were: 1245 nt, 1815 nt and 1498 nt for pRF, pRVcipF and pRmRNA1, respectively).

Finally, to eliminate the possibility of ribosome shunting or read-through of the renilla stop codon, the length of the produced firefly luciferase protein was verified by Western blot (Fig. S4C). Whereas no protein was detected either for pRF or the mock transfections, a unique band of the expected size (62 kDa) was observed when pRVcipF and pRmRNA1F constructs were transfected in COS-7 cells, showing that the synthesis of the firefly luciferase is indeed initiated at the expected AUG.

In order to confirm that the IRES function of mRNA1 is also conserved in other mammals, the mouse 5′-UTR, which has the most divergent sequence (Fig. 1B) was tested using the pRF system. The mouse 5′-UTR controlled expression of firefly luciferase with the same efficiency as the human sequence (Fig. 5C).

Looking for control of IRES-dependent expression

Cellular IRESs are often expressed when cap-dependent translation is inhibited either by stress or under particular physiological conditions.24-26 Therefore, several conditions where mRNA1 IRES mediated expression could be affected, were tested.

First, different stress conditions were applied to cells transfected with bicistronic constructs: (i) starvation by omitting the serum in the medium; (ii) glucose deprivation using a low glucose medium; (iii) mTOR pathway inhibition in the presence of 100 nM Rapamycin; and (iv) hypoxia with the addition of 150 µM CoCl2. Any particular stimulation either with Vcip, or GARS mRNA1 were observed (data not shown).

Another consideration was the presence of a putative 5 base-pair sequence (5′-152CGGAG156-3′) complementarity to the 3′-extremity of 18S rRNA (5′-1839UUCCG1843-3′). Mutating this sequence in pRmRNA1F allowed testing if these nucleotides could stabilize the mRNA on the 40S subunit and facilitate AUG0/AUGcyto recognition by the ribosome. Again, in this context, the mutations did not lead to reduction of IRES activity (data not shown).

Finally, because it has been shown that GARS binds to and stimulates translation from the poliovirus IRES,14 GARS was cotransfected with the bicistronic constructs and tested whether GARS co-expression could modify firefly luciferase synthesis. Again, this did not alter mRNA1 IRES controlled expression of firefly luciferase (data not shown).

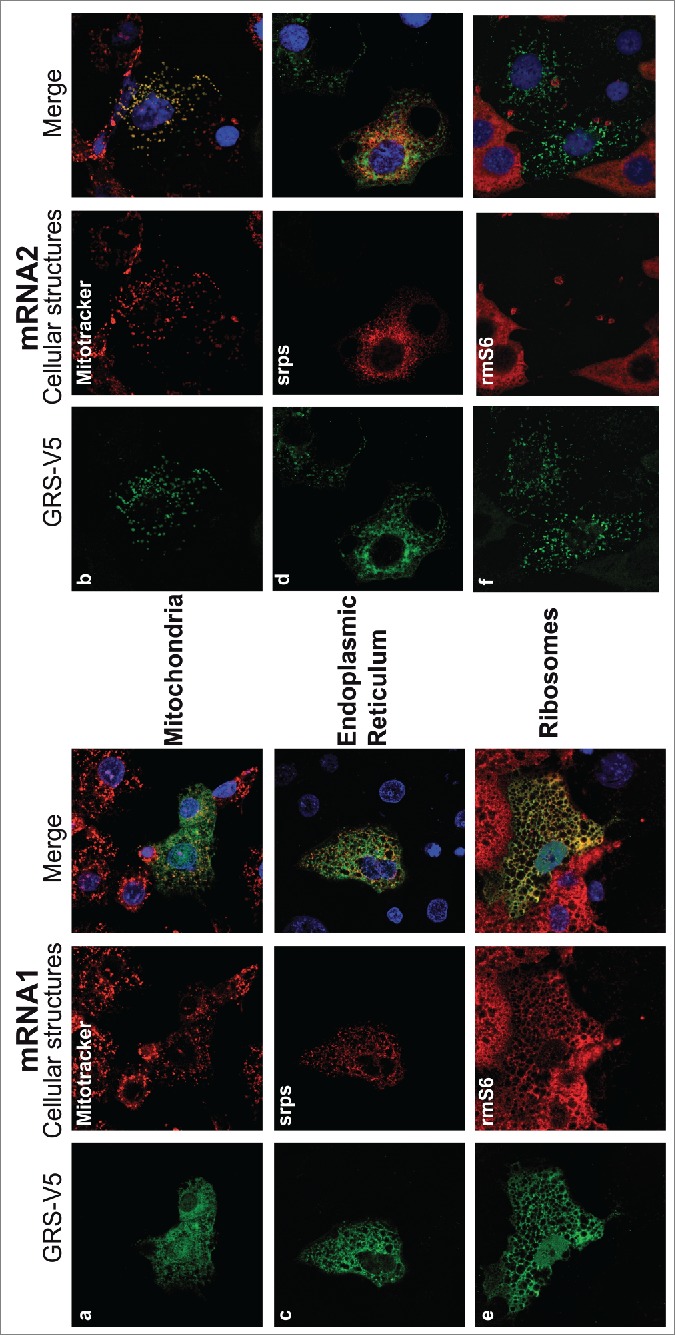

The mRNA1 GARS product colocalizes with endoplasmic reticulum associated ribosomes

Contrary to mRNA2, the GARS produced by mRNA1 showed some ambiguous localization (Fig. 2B). Indeed, the GARS produced from mRNA1 organizes in a network. Thus additional immunolocalization assays were performed in the presence of digitonin, in order to extract the soluble cytoplasmic GARS, leaving behind only the GARS attached to cellular structures (Fig. 6; Fig. S3B). Colocalization assays between GARS-V5 and the Mitotracker label confirmed that the GARS translated from mRNA2 is indeed present in the mitochondria whereas most of the GARS translated via the mRNA1 IRES is clearly associated with another cellular structure (compare panels a and b). To identify the nature of this cellular structure, mRNA1 and mRNA2 constructs were co-expressed with the Signal Recognition Particle (SRP) receptor B subunit which is an integral ER protein (coupled to DsRed: Srprb-DsRed) or with the endogenous ribosomal protein rm6S. mRNA2 does not show obvious colocalization with the ER or with ribosomes (panels e and f), but mRNA1 behaves differently. Indeed, panel c shows that the GARS network was in close proximity to the ER. Besides, it superimposed clearly with ribosomes (panel e), suggesting that the mRNA1 product interacts with ER-associated translating ribosomes. It is known that the large ribosomal subunit is tightly bound to the ER membrane, whereas the small subunit can freely exchange between soluble and membrane‐bound states.27 Thus, antibodies directed against the small subunit allowed the detection of actively translating ribosomes that are bound to the ER. Because transfected genes recruit most of the translating ribosomes available in the cell, expression of mRNA1 GARS increased considerably the ER-bound ribosomes density and confirmed that mRNA1 is translated locally. On the contrary, the absence of ER-bound ribosomes proved that mRNA2 is decoded by cytosolic ribosomes, which are washed away by the digitonin treatment (untransfected neighboring cells still contain ER-bound translating ribosomes). In this case, only the mitochondrial GARS is detected.

Figure 6.

Differential colocalization of GARS with subcellular structures, depending on mRNA isoforms. GARS-V5 was expressed from mRNA1 (left) or mRNA2 (right). GARS-V5 localizations (green) were compared with red markers for mitochondria (a and b, Mitotracker), ER protein (c and d, SRPs-DsRed) and endogenous ribosomal protein S6 (e and f, rmS6). In order to remove the background noise due to the cytosolic GARS, transfected COS-7 cells were first permeabilized with digitonin. This treatment strips the plasma membrane, so that cells lose most of their cytosolic content but retain intact mitochondria and ER. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Corresponding co-localization statistics are indicated in Figure S3B.

This observation led us to compare the localization of both GARS mRNA isoforms by subcellular fractionation experiments (Fig. S5); Contrary to P450 cytochrome oxidase, which is an integral ER membrane protein, GARS did not co-purify with the ER fraction and confirmed that the GARS mRNA1 product diffuses in the cytosol. However, both mRNA1 and mRNA2 were found attached to the ER fraction, indicating that the localization signal is present in the ORF sequence.

Insights into mRNA1 IRES structure

We faced technical problems in studying the mRNA1 IRES structure in solution due to intricate and stable IRES folding that hindered all our attempts to solve its structure. Thus, bioinformatics tools were used to build a structural model of the GARS IRES based on sequence alignments with mammalian 5′-UTRs (Fig. S6). The two-dimensional model shows a 3-way junction linking Watson-Crick helices: (i) the 5′- and 3′-ends interact together to form a double stranded domain (helix I) containing both AUG0 and AUGcyto, (ii) the left arm (helix II) covers most of the uORF and displays AUGmito and the uORF stop codon, (iii) the right arm (helix III) corresponds to the rest of the MTS coding region of the mitochondrial GARS. Such a structure presents strong potential for tertiary interactions as well as extensive major/minor groove contacts between helices.28 When the 50 nucleotides present at the 5′-end of mRNA1 were deleted, the firefly activity decreased to its background activity (Fig. 5D), whereas progressive shortening at the 3′-end of mRNA1 5′-UTR led to progressive losses in IRES activity (Fig. 5D). Thus, any change in the sequence destabilizes the structure and affects the IRES initiation and/or reinitiation mechanisms. This clarifies what was observed with the mRNA1 mutants missing AUG0 (mutants b, c and f). In the case of an exclusive IRES initiation mechanism, these mutants should be completely inactive in translation. However, because AUG0 is involved in the structure of helix I, its mutation could lead to unfolding of this domain and introduce enough instability so that cap-dependent initiation and ribosome scanning can occur in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 3).

Discussion

A previous study used primer extension to analyze fetal liver cDNA encoding human glycyl-tRNA synthetase (GARS) and identified a single mRNA isoform.16 This mRNA encoded the 2 initiator codons dedicated to the mitochondrial (AUGmito) and the cytosolic (AUGcyto) forms of the enzyme. The 5′-UTR was 371 nucleotides long and contained 3 other AUG codons upstream of AUGmito. However, despite repeated attempts, the authors were unable to confirm the mRNA TSS by 5′-RACE or RNase protection assays.17 Surprisingly, they also observed that an effective promoter activity was present 55 base pairs downstream of the identified TSS, suggesting that this proximal promoter element may be important for GARS expression. In our study, we confirmed this assumption by identifying 2 shorter mRNA isoforms in 6 different adult tissues (heart, brain, bone marrow, muscle, spleen and liver). These two mRNA isoforms (mRNA1 and mRNA2) both contained AUGmito and AUGcyto. Yet, the longer 5′-UTR (mRNA1) contained only 90 nucleotides upstream of AUGmito and a unique additional AUG (AUG0). Translation of the shorter mRNA2 produces both the mitochondrial and the cytosolic GARS, suggesting a leaky scanning mechanism,29,30 whereas the longer mRNA1 produces only the cytosolic GARS (Fig. 2B). Both mRNAs were found in the DBTSS,18 however their relative abundances (Fig. S2) did not allow determining any tissue specific expression profile.

Further analysis of mRNA1 identified the presence of an IRES structure. Indeed, although the mature mRNA1 (like other cellular IRESs) contains a 5′-cap structure, it drives cap-independent translation as expected for functional IRESs. The GARS IRES activity is substantial, it is about 70 % of the vascular endothelial growth factor and type 1 collagen-inducible protein (VCIP) IRES activity (Fig. 5). Since Vcip is the most efficient IRES element previously characterized (Licursi et al., 2011), GARS IRES is more efficient than most of the viral and cellular IRES identified today.

The complexity of the initiation mechanism that characterizes mRNA1 is further increased by the presence of a short uORF initiating at AUG0 encoding a putative 32 residue peptide. Interestingly, this particular organization of the 5′-UTR is conserved in all the mammalian genes encoding GARS (Fig. 1B). The introduction of a frameshift mutation between AUG0 and AUGmito showed that AUG0 is the only initiator codon used to initiate mRNA1 translation and that the peptide is potentially produced. The peptide sequence is not strictly conserved between mammals, however they all are proline and arginine rich. It is difficult to speculate about its hypothetical function since this peptide was not detectable by mass spectrometry (neither in cell extracts, nor in cell culture supernatants), due to its size, low abundance or rapid degradation in the cell. The presence of such a uORF usually reduces the translation efficiency of the downstream ORF (reviewed in).31 Indeed, in mRNA1, because the uORF sequence covers AUGmito, presumed translation of this peptide specifically hinders the production of the mitochondrial GARS. In contrast, uORF translation terminates before AUGcyto, allowing translation of the cytosolic GARS by reinitiating at the AUG directly downstream of the stop codon.32 Efficient reinitiation commonly occurs after translation of short ORFs and can be modulated in response to environmental changes.33 Moreover, genome wide bioinformatic analyses show that >45% of mammalian mRNAs contain at least one uORF,31 and they are frequently translated.34 We cannot exclude that mRNA1 sequence can occasionally be used for cap-dependent initiation, even if the short 5′-UTR upstream of AUG0 does not support this option. Moreover, mRNA1 is highly conserved among mammals (Fig. 1B), the mouse sequence being the most divergent. Still, the mouse IRES domain shows the same activity as the human IRES domain (Fig. 5C), indicating that not only the sequence, but also the function of this 5′ domain is conserved in mammals.

Even more striking is the specific colocalization of the mRNA1 GARS product and ER-bound ribosomes (Fig. 6). There is increasing evidence that many mRNAs encoding cytosolic proteins are zip-coded to the ER for localized translation,35-37 although clear RNA motifs have not yet been identified. Using HEK297 cell fractionation and ribosome profiling, David and coworkers performed a genomic survey of the subcellular organization of mRNA translation.38 Interestingly, in their study, 21% of mRNAs encoding GARS are bound to the ER; yet, 33% of GARS mRNAs were more heavily loaded with ER-bound ribosomes, indicating that this mRNA is preferentially decoded at the ER. In the present study both GARS mRNA isoforms, mRNA1 and mRNA2 bind the ER (Fig. S5), thus sharing a common targeting signal. However, only the IRES containing mRNA1 is translated locally. It suggests that (i) GARS mRNA targeting to ER-bound ribosomes is driven by the IRES function of mRNA1 and (ii) this local translation may modulate GARS expression. These results provide evidence that subdividing mRNA2 and mRNA1 translation between the cytosol and the ER respectively may control the post-transcriptional regulation of GARS expression.

IRES domains are found in several mRNAs encoding dendritic proteins, including activity-regulated cytoskeletal protein, the α subunit of calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II.39 Likewise, all studies on CMT type 2D converge toward a peculiar expression and function of GARS in peripheral motor and sensory neurons.5-7,9,10 However, it cannot be deduced from the present study that GARS IRES-containing mRNA1 modulates neurotoxicity of CMT mutants. Indeed, the absence of the IRES sequence in invertebrate GARS genes does not prevent GARS-associated CMT in Drosophila.40 This implies that IRES dependent expression of GARS is not involved in the mechanism responsible for CMT or that GARS translation is regulated via an alternative mechanism in Drosophila. In fact, post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms that control aaRSs expression are not conserved among aaRSs or in evolution.41

Many proteins encoded by IRES containing mRNAs also play important roles in cell survival, proliferation, cell cycle and angiogenesis, all processes that are important in cancer initiation and progression.24,25 In mammals, Park and collaborators showed that upon Fas-ligand binding, macrophages (human U937 and mouse RAW264.7 cell lines) release GARS with anti-tumor activities,13 suggesting that GARS expression/secretion controls tumorogenesis. In this particular context, could the mRNA1-driven translation at the ER trigger the secretion of a specific extracellular GARS pool? Could it also trigger the secretion of antigenic GARS engendering autoantibodies in the blood of polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients?.42,43

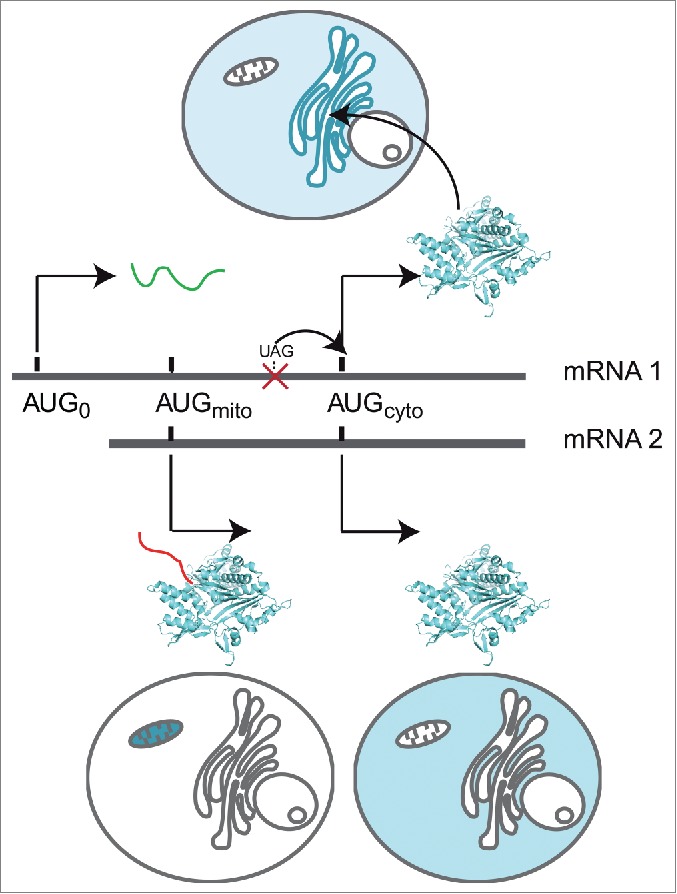

This work shows that the 5′-extremity of GARS mRNA1 is the site of intricate regulatory mechanisms connecting cap-independent translational initiation and subcellular localization of human GARS (summarized in Fig. 7). Such complexity matches the range of uncovered moonlighting activities for mammalian GARS connected with tissue-specific expression or extracellular localization.4,13,14 By exploiting the differential translation activities and localization of mRNA1 and mRNA2, the cell may control the level of GARS synthesis. In this context, a fraction of GARS specifically translated at the ER would influence cellular responses distal to the cell cytosol. An alignment-based structural model of this IRES sequence gives a rough idea of its structure. However, since cellular IRESs do not share any common structural motif,44 it is difficult to draw a model for translation initiation of mRNA1. Further studies to understand the dynamics of this IRES structure will be decisive to comprehend both how this IRES captures the translation machinery to initiate at AUG0 and how it drives reinitiation at AUGcyto. Could disequilibrium between mRNA1 and mRNA2 concentrations affect the ER/cytoplasmic or the mitochondrial GARSs specifically in different cell types and affect some alternative function? Could such an imbalance disturb GARS expression and result in sick cells or GARS secretion? Because IRES structures may respond to changing cellular conditions, it is essential now to identify IRES trans-acting factors involved in mRNA1 translation to get information about the role of this specific GARS.

Figure 7.

Suggested models. Summary of GARS expression from mRNA1 and mRNA2 isoforms: mRNA2 codes both the mitochondrial (red MTS) and the cytosolic GARSs using a leaky scanning mechanism. Only 2 initiation codons are recognized in mRNA1, due to a uORF containing an IRES, which hinders mitochondrial GARS synthesis. Translation initiation at AUG0 leads (i) to the synthesis of a short peptide (green) and (ii) to the subsequent reinitiation at AUGcyto, allowing translation of GARS on ER-bound ribosomes (blue) and its subsequent diffusion in the cytosol.

Materials and Methods

RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-RACE)

Identification of GARS mRNA 5′-and 3′-UTRs was performed using the First Choice RLM-RACE kit (Ambion, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Experiments were performed with 10 µg of highly pure total RNA from 6 different tissues (liver, spinal cord, brain, skeletal muscle, heart and spleen, purchased from Ambion).

For 5′-RLM-RACE, RNAs were first decapped (as appropriate), ligated to a 5′-adaptor and reverse transcribed using a specific reverse primer 5′-TTCCTCGATTGTCTCTTTTTT-ACCAGTCTCTTGC-3′, hybridizing between nucleotides (nt) 2184 and 2216 at the very end of the predicted mitochondrial GARS ORF sequence. The resulting cDNAs were then subjected to 2 nested PCRs in the presence of 5% DMSO. PCRs were performed with 2 primers complementary to the 5′-adaptor sequence and 2 nested primers hybridizing the mitochondrial GARS ORF sequence: outer primer 5′-CTCCATTTTTTACGTCTTTCA-CCATGAAGTCAGC-3′ (nt 595 to 628), inner primer 5′-GGGCTGTAACGCCAGCTCCT-TTGCTTCCAGAACCCTC-3′ (nt 306 to 342).

Alternatively the 3′-RLM-RACE was performed on complete cDNAs reverse transcribed using a primer hybridizing mRNA polyA tails and containing a 3′-adaptor sequence. PCRs were performed with 2 primers complementary to the 3′-adaptor sequence and 2 nested primers hybridizing the GARS ORF sequence: outer primer 5′-ACTTTGACACAGTGAACA-AGAC-3′ (nt 2018-2039) and inner primer 5′-AGCATAGTCCAAGACCTAGCCAATGG-3′ (nt 2110-2135).

PCR-amplified fragments were cloned into the pDrive cloning vector (PCR cloning kit, Qiagen) and sequenced.

Construction of GARS mammalian expression vectors

GARS mRNA sequences were introduced into a modified pcDNA3.1 vector for expression. In order to transcribe mRNAs beginning with their exact 5′-extremity, the “extra” sequence present between the pcDNA3.1 transcription start site and the KpnI restriction site was removed by mutagenesis (Phusion Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, Thermo Scientific). The sequence of the GARS ORF was generated by RT-PCR from HeLa cell total RNA, fused to a C-terminal V5 epitope sequence and introduced in the modified pcDNA3.1 between the KpnI and XbaI restriction sites. Then both 5′-UTR sequences were PCR amplified from brain cDNA (Ambion) and introduced between the KpnI restriction site and the unique internal NheI restriction site present at nt 205 in the mitochondrial GARS ORF. Mutants were generated by replacing each putative ATG initiator codon by the ATA sequence (Phusion Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit). A 5′ stable hairpin structure.19 was introduced at the KpnI site using 2 overlapping primers: 5′-AATTGGTACCTTTGCAAAAAGCTCCACCACGGCCCAAGCTTGGGC-3′ and 5′- TTA-AGGTACCAAGCTCCACCACGGCCCAAGCTTGGG-3′.

Bicistronic vectors pRF and pRVcipF were a kind gift from Catherine Schuster, described previously.20 Briefly, pRF contains 2 ORFs, the first one coding for the Renilla luciferase and the second for the Firefly luciferase. Renilla luciferase is expressed constitutively (cap-dependant translation), while Firefly is expressed only if an IRES sequence is introduced in the intercistronic region. The human mRNA1 5′-end sequence and different variants as well as the mouse mRNA1 sequence were inserted in the intercistronic region between EcoRI and NcoI to obtain the pRmRNA1F vector and the mRNA1 structure deletants. pRF, pRVcipF and pRmRNA1F promotorless constructs were created by excision of the SV40 promoter (between SmaI and EcoRV sites).

Cell culture and transfection

COS-7 cells were cultured in DMEM GlutaMAX growth medium (Life Technologies) containing 4,5 mg/L glucose, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin and 10% fetal calf serum. Cells were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Twenty-four hours prior to transfection COS-7 cells were seeded into 6 (or 12) well plates, at a density of 2.105 (or 105) cells per well and cells were then transfected with 100 (or 50 ng) of pcDNA3.1 (or pRF) constructs, using the Nanofectin transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (PAA labs). After 24 hours incubation, cells were washed with PBS (Life Technologies) and collected for further investigations.

Immunostaining

For immunolocalization assays, cells were seeded directly on coverslips treated with 10 µg/cm2 collagen type I (BD Bioscience). Twenty-four hours after transfection, mitochondria were labeled with 50 nM MitoTracker Orange CMTMRos (Mitochondrion Selective Probe from Life Technologies) for 30 min at 37 °C. When needed, extraction of free cytoplasmic proteins was performed in the presence of 25 µg/mL digitonin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes on ice. Cells were then washed twice in PBS, fixed for 10 min with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and permeabilized in ice-cold methanol for 5 minutes. Cells were washed with PBS and blocked in 3% BSA (Euromedex) for one hour.

Immunostaining of GARS was performed with FITC-conjugated mouse anti-V5 monoclonal antibody from Life Technologies (1:500) at 37 °C for 2 hours. Ribosomes were labeled first under the same conditions with rabbit monoclonal anti-S6 ribosomal protein antibody (Pierce) and further detected with TRITC-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (40 min at 37 °C). Slides were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich), mounted in anti-fading solution and visualized under confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 780 Confocal system, Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany). The resulting images were analyzed using Image J Software.

Western blot

Twenty-four hours after transfection, COS-7 cells were incubated in lysis buffer (Promega) for 15 min at RT and the protein concentration was measured using the Bradford protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad). Equal quantities of total protein were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). The membrane was blocked for 1 hour in 1X TBS containing 0.5% Tween20, 3% non-fat dry milk and then incubated with (i) mouse anti-V5 monoclonal antibody HRP–conjugated (1:5000; Life Technologies) for 2 hours, (ii) rabbit anti-firefly luciferase polyclonal (1:5000; Pierce) for 1 hour, or (iii) mouse monoclonal anti-ßActin (1:10000; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hour. Secondary sheep anti-mouse antibody HRP–conjugated was from GE Healthcare and goat anti-rabbit HRP–conjugated from Bio-Rad. All incubations were carried out at room temperature.

Subcellular fractionation

ER fractions were isolated as described.45 Cells (30.106) were transfected with 5 µg of pCDNA3.1(Mock), pCDNA3.1-mRNA1 or pCDNA3.1-mRNA2. With this protocol, ER and mitochondria were efficiently separated on sucrose gradients. For Western blot analysis, 4 to 5 µg of proteins were probed with anti-P450 cytochrome oxidase (Genetex), anti-GARS (Abcam) and anti-V5 antibodies. For RT-PCR, RNA samples were purified using the NucleoSpin RNA kit (Macherey-Nagel), following the manufacturer's protocol. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed in 20 µl reactionswith 200 ng RNA and 100 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Ambion). PCR were carried out on 2 µl of RT reaction. Fractionation experiments were performed in 4 different conditions: +EDTA/+cycloheximide (CHX), +EDTA/-CHX, -EDTA/+CHX and -EDTA/CHX. In the absence of EDTA, the ER fraction is still contaminated with GARS.

Luciferase activity

Assays were conducted as indicated in the dual luciferase reporter assay system manual (Promega, France) and error bars were calculated from 3 independent experiments.

In vitro transcription of GARS mRNA and in vitro translation

The V5 epitope was replaced by the sequence corresponding to the 3′-UTR of the GARS mRNA, and inserted immediately downstream of the GARS constructs (XbaI and XhoI). The T7 RNA polymerase promoter and a polyA tail (40 As) were then introduced by PCR at the 5′- and 3′-ends of each DNA template, respectively. In vitro transcription was performed in reaction mixtures containing 40 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.1 (37°C), 22 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithioerythritol, 0.1 mM spermidine, 4 mM ATP, CTP, and UTP, 1 mM GTP, 2 mM 3′-O-Me-m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G [m7G] cap structure analog (BioLabs), 40 ng/µL DNA template and 5 µg/mL T7 RNA polymerase. Transcription mixtures were incubated for 2 h at 37°C and reactions were stopped by acidic phenol/chloroform extraction. RNA transcripts were purified on Nap5 columns (GE-Healthcare) to remove non-incorporated ribonucleotides, ethanol precipitated, and quantified on a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer. For cap-dependant/independant in vitro translation assays, mRNAs were synthetized in the presence of 10 mM 3′-O-Me-m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G [m7G] or G(5′)ppp(5′)A [Ap3G] cap structure analogs (BioLabs).

In vitro translation reactions were carried out with 5 nM mRNA and 10 µCi [35S] methionine, in rabbit reticulocytes or wheat germ extract from Promega, according to the manufacturer's instructions, for 60 minutes at 30°C or for 2 hours at 25 °C, respectively. Translated proteins were further analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography and quantification.

RT-PCR analysis of pRF constructs

Twenty-four hours after transfection, total RNA was extracted from transfected COS-7 cells using the TRI Reagent→ Protocol (Sigma-Aldrich). Extracted RNA was treated with DNaseI: 10 µg of RNA were incubated in the presence of 5U of DNaseI (Sigma-Aldrich) for 40 minutes at 37°C. DNaseI-treated RNA (0.5 µg) was reverse transcribed for 1 hour at 42 °C, using the first strand cDNA synthesis kit (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer's protocol. PCR reactions were performed with the Phusion Taq polymerase (Thermo-Scientific) on 1 µL of reverse transcription product in the presence of 3% DMSO.

Multi-alignment-based structure

A consensus structure was deduced from all mRNA1 mammalian sequences using the structural aligner LocARNA.47 This structure was re-evaluated and curated with the last version of the graphical tool Assemble.48

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Aknowledgments

We thank Alain Lescure and Catherine Schuster for support and discussions and Rebecca Wagner Alexander and Tamara Hendrickson for comments on the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

Funding

This work was supported by the Center National de la Recherche Scientifique; Strasbourg University; and the French Association for Myopathies (AFM) [grant numbers 15387, 16411].

References

- 1.Park SG, Ewalt KL, Kim S. Functional expansion of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and their interacting factors: new perspectives on housekeepers. Trends Biochem Sci 2005; 30:569-74; PMID:16125937; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hausmann CD, Ibba M. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complexes: molecular multitasking revealed. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2008; 32:705-21; PMID:18522650; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00119.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim S, You S, Hwang D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and tumorigenesis: more than housekeeping. Nat Rev Cancer 2011; 11:708-18; PMID:21941282; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc3124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo M, Schimmel P. Essential nontranslational functions of tRNA synthetases. Nat Chem Biol 2013; 9:145-53; PMID:23416400; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nchembio.1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonellis A, Ellsworth RE, Sambuughin N, Puls I, Abel A, Lee-Lin SQ, Jordanova A, Kremensky I, Christodoulou K, Middleton LT, et al.. Glycyl tRNA synthetase mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 72:1293-9; PMID:12690580; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1086/375039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antonellis A, Lee-Lin SQ, Wasterlain A, Leo P, Quezado M, Goldfarb LG, Myung K, Burgess S, Fischbeck KH, Green ED. Functional analyses of glycyl-tRNA synthetase mutations suggest a key role for tRNA-charging enzymes in peripheral axons. J Neurosci 2006; 26:10397-406; PMID:17035524; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1671-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motley WW, Talbot K, Fischbeck KH. GARS axonopathy: not every neuron's cup of tRNA. Trends Neurosci 2010; 33:59-66; PMID:20152552; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee HJ, Park J, Nakhro K, Park JM, Hur Y-M, Choi B-O, Chung KW. Two novel mutations of GARS in Korean families with distal hereditary motor neuropathy type V. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2012; 17:418-21; PMID:23279345; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00442.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao P, Fox PL. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in medicine and disease. EMBO Mol Med 2013; 5:332-43; PMID:23427196; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/emmm.201100626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallen RC, Antonellis A. To charge or not to charge: mechanistic insights into neuropathy-associated tRNA synthetase mutations. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2013; 23:302-9; PMID:23465884; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gde.2013.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahler M, Miller FW, Fritzler MJ. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and the anti-synthetase syndrome: A comprehensive review. Autoimmunity Reviews 2014; 13:367-71; PMID:24424190; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mun J, Kim Y-H, Yu J, Bae J, Noh D-Y, Yu M-H, Lee C. A proteomic approach based on multiple parallel separation for the unambiguous identification of an antibody cognate antigen. Electrophoresis 2010; 31:3428-36; PMID:20872419; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/elps.201000136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park MC, Kang T, Jin D, Han JM, Kim SB, Park YJ, Cho K, Park YW, Guo M, He W, et al.. Secreted human glycyl-tRNA synthetase implicated in defense against ERK-activated tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2012; 109:E640-E7; PMID:22345558; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1200194109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreev DE, Hirnet J, Terenin IM, Dmitriev SE, Niepmann M, Shatsky IN. Glycyl-tRNA synthetase specifically binds to the poliovirus IRES to activate translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res 2012; 40:5602-14; PMID:22373920; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gks182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiba K, Schimmel P, Motegi H, Noda T. Human glycyl-tRNA synthetase. Wide divergence of primary structure from bacterial counterpart and species-specific aminoacylation. J Biol Chem 1994; 269:30049-55; PMID:7962006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams J, Osvath S, Khong TF, Pearse M, Power D. Cloning, sequencing and bacterial expression of human glycine tRNA synthetase. Nucleic Acids Res 1995; 23:1307-10; PMID:7753621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/23.8.1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mudge SJ, Williams JH, Eyre HJ, Sutherland GR, Cowan PJ, Power DA. Complex organisation of the 5′-end of the human glycine tRNA synthetase gene. Gene 1998; 209:45-50; PMID:9524218; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00007-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki A, Wakaguri H, Yamashita R, Kawano S, Tsuchihara K, Sugano S, Suzuki Y, Nakai K. DBTSS as an integrative platform for transcriptome, epigenome and genome sequence variation data. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43:D87-91; PMID:25378318; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gku1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozak M. Influences of mRNA secondary structure on initiation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1986; 83:2850-4; PMID:3458245; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoneley M. C-Myc 5′ untranslated region contains an internal ribosome entry segment, Published online: 21 January 1998; 16:423-8; PMID:9467968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coldwell MJ, Mitchell SA, Stoneley M, MacFarlane M, Willis AE. Initiation of Apaf-1 translation by internal ribosome entry. Oncogene 2000; 19:899-905; PMID:10702798; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1203407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blais JD, Addison CL, Edge R, Falls T, Zhao H, Wary K, Koumenis C, Harding HP, Ron D, Holcik M, et al.. Perk-Dependent Translational Regulation Promotes Tumor Cell Adaptation and Angiogenesis in Response to Hypoxic Stress. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26:9517-32; PMID:17030613; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.01145-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vopalensky V, Masek T, Horvath O, Vicenova B, Mokrejs M, Pospisek M. Firefly luciferase gene contains a cryptic promoter. RNA 2008; 14:1720-9; PMID:18697919; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.831808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spriggs KA, Bushell M, Willis AE. Translational regulation of gene expression during conditions of cell stress. Mol Cell 2010; 40:228-37; PMID:20965418; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spriggs KA, Stoneley M, Bushell M, Willis AE. Re-programming of translation following cell stress allows IRES-mediated translation to predominate. Biol Cell 2008; 100:27-38; PMID:18072942; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/BC20070098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komar AA, Hatzoglou M. Cellular IRES-mediated translation: The war of ITAFs in pathophysiological states. Cell Cycle 2011; 10:229-40; PMID:21220943; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.10.2.14472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seiser RM, Nicchitta CV. The fate of membrane-bound ribosomes following the termination of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:33820-7; PMID:10931837; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M004462200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lescoute A, Westhof E. Riboswitch structures: purine ligands replace tertiary contacts. Chem Biol 2005; 12:10-3; PMID:15664510; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozak M. Pushing the limits of the scanning mechanism for initiation of translation. Gene 2002; 299:1-34; PMID:12459250; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0378-1119(02)01056-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinnebusch AG. Molecular mechanism of scanning and start codon selection in eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2011; 75:434-67, first page of table of contents; PMID:21885680; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MMBR.00008-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calvo SE, Pagliarini DJ, Mootha VK. Upstream open reading frames cause widespread reduction of protein expression and are polymorphic among humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2009; 106:7507-12; PMID:19372376; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0810916106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11:113-27; PMID:20094052; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrm2838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson RJ, Hellen CU, Pestova TV. Termination and post-termination events in eukaryotic translation. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2012; 86:45-93; PMID:22243581; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/B978-0-12-386497-0.00002-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ingolia NT, Lareau LF, Weissman JS. Ribosome Profiling of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells Reveals the Complexity and Dynamics of Mammalian Proteomes. Cell 2011; 147:789-802; PMID:22056041; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hervé C, Mickleburgh I, Hesketh J. Zipcodes and postage stamps: mRNA localisation signals and their trans-acting binding proteins. Brief Funct Genomics Proteomic 2004; 3:240-56; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bfgp/3.3.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weis BL, Schleiff E, Zerges W. Protein targeting to subcellular organelles via MRNA localization. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1833:260-73; PMID:23457718; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hermesh O, Jansen RP. Take the (RN)A-train: Localization of mRNA to the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1833:2519-25; PMID:23353632; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.David A, Netzer N, Strader MB, Das SR, Chen CY, Gibbs J, Pierre P, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. RNA Binding Targets Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases to Translating Ribosomes. J Biol Chem 2011; 286:20688-700; PMID:21460219; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.209452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pinkstaff JK, Chappell SA, Mauro VP, Edelman GM, Krushel LA. Internal initiation of translation of five dendritically localized neuronal mRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001; 98:2770-5; PMID:11226315; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.051623398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ermanoska B, Motley WW, Leitao-Goncalves R, Asselbergh B, Lee LH, De Rijk P, Sleegers K, Ooms T, Godenschwege TA, Timmerman V, et al.. CMT-associated mutations in glycyl- and tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases exhibit similar pattern of toxicity and share common genetic modifiers in Drosophila. Neurobiol Dis 2014; 68:180-9; PMID:24807208; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryckelynck M, Giege R, Frugier M. tRNAs and tRNA mimics as cornerstones of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase regulations. Biochimie 2005; 87:835-45; PMID:15925436; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Targoff IN. Autoantibodies to aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases for isoleucine and glycine. Two additional synthetases are antigenic in myositis. J Immunol 1990; 144:1737-43; PMID:2307838 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Targoff IN, Trieu EP, Plotz PH, Miller FW. Antibodies to glycyl-transfer RNA synthetase in patients with myositis and interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum 1992; 35:821-30; PMID:1622421; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/art.1780350718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baird SD, Lewis SM, Turcotte M, Holcik M. A search for structurally similar cellular internal ribosome entry sites. Nucleic Acids Res 2007; 35:4664-77; PMID:17591613; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkm483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bozidis P, Williamson CD, Colberg-Poley AM. Isolation of endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and mitochondria-associated membrane fractions from transfected cells and from human cytomegalovirus-infected primary fibroblasts. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 2007; Chapter 3:Unit 3 27; PMID:18228515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J. T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol 2000; 302:205-17; PMID:10964570; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Will S, Joshi T, Hofacker IL, Stadler PF, Backofen R. LocARNA-P: accurate boundary prediction and improved detection of structural RNAs. RNA 2012; 18:900-14; PMID:22450757; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1261/rna.029041.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jossinet F, Ludwig TE, Westhof E. Assemble: an interactive graphical tool to analyze and build RNA architectures at the 2D and 3D levels. Bioinformatics 2010; 26:2057-9; PMID:20562414; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.