To the editor

Evidence suggests that a substantial proportion of Ebola virus infections are asymptomatic1–2, a factor overlooked by recent Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak summaries and projections3–4. In particular, one post-EVD outbreak serosurvey1 found that 71% of seropositive individuals had not experienced diseaseanother study2 found that 46% of asymptomatic close contacts of EVD cases were seropositive. Although asymptomatic infections are unlikely to be infectious2, they may confer protective immunity and thus have important epidemiological consequences.

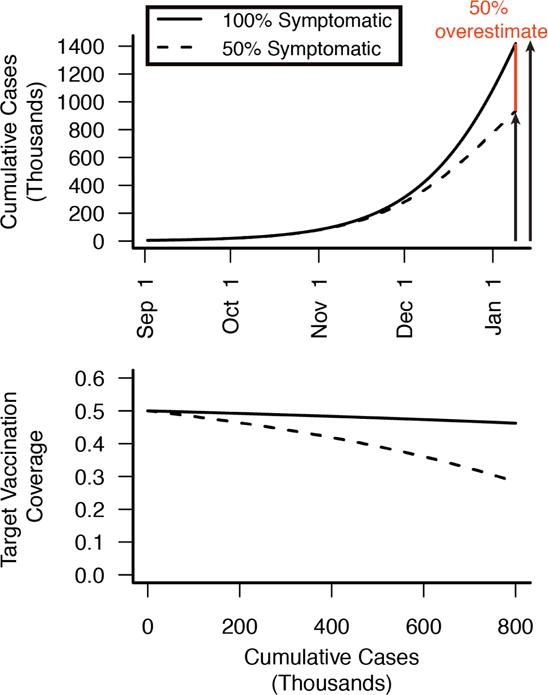

While the ongoing epidemic clearly requires a forceful response, forecasts that ignore naturally acquired immunity from asymptomatic infections overestimate incidence late in epidemics. We illustrate this point by comparing the projections of two simple models based on the EVD epidemic in Liberia, one that does not account for asymptomatic infections and another that assumes 50% of infections are asymptomatic and induce protective immunity. In both models the basic reproduction number (R0the average number of secondary infectious cases resulting from a single infectious case) is identical and based on recently published models3–4. The figure (Panel A) shows the projected incidence through time. Although the initial outbreaks are virtually identical, by January 10, the model without asymptomatic infections projects 50% more cumulative symptomatic cases than the model that accounts for asymptomatic infection. This difference arises because asymptomatic infection contributes to herd immunity and its dampening effect on epidemic spread.

Figure. Effects of immunizing asymptomatic infections on Liberia outbreak projections and vaccination requirements.

(A) Projected cumulative incidence including and excluding asymptomatic infection (50% symptomatic, dashed line100% symptomatic, solid line). If 50% of infections are asymptomatic, then models overlooking asymptomatic infection will overestimate disease incidence later in the epidemic, as individuals who were asymptomatically infected become immune and contribute to herd immunity. By January 10, 2015 models ignoring asymptomatic immunity overestimate cumulative incidence by 50% (red). (B) Population-level vaccine coverage (proportion vaccinated) needed to contain the Ebola epidemic (reduce R0 below one) in scenarios with no asymptomatic infection (solid line) and 50% asymptomatic infection (dashed line). Vaccination targets decrease throughout the epidemic as natural immunity builds up in the population, through both symptomatic and asymptomatic infection. Code for models and calculations is available at http://ebola.ici3d.org.

Widespread asymptomatic immunity would likewise have implications for EVD control measures, and should be considered when planning intervention strategies. For instance, should a safe and effective vaccine become available, the vaccination coverage required for elimination will depend on levels of pre-existing immunity in the population (Figure Panel B). Immunity resulting from asymptomatic infections should reduce the intervention effort needed to interrupt transmission, but may also complicate the design and interpretation of vaccine trials. Trials and interventions are likely to target exactly those high risk populations most likely to have been asymptomatically immunized. Thus, for evaluations of vaccines and other countermeasures, baseline serum should be collected to both estimate intervention effectiveness and to improve our understanding of asymptomatic immunity. Additionally, evaluation of intervention measures should account for the contribution of asymptomatic immunity in curbing epidemic spread.

Asymptomatic infection could also potentially be directly harnessed to mitigate transmission. If individuals who have cleared asymptomatic infections could be identified reliably, and if they are indeed immune to symptomatic re-infection, they could potentially be recruited to serve as caregivers or to undertake other high-risk disease control tasks, providing a buffer akin to that of ring vaccination. Recruiting such individuals may be preferable to enlisting survivors of symptomatic EVD, since survivors may suffer psychological trauma or stigmatization and be relatively less numerous, given the asymptomatic proportions suggested in previous studies1–2 and the low survival rate of symptomatic cases3. For example, health care workers with natural immunity acquired from asymptomatic infection, if identified, could be allocated to care for acutely ill and infectious patients, minimizing disease spread to susceptible health care workers.

All of the conclusions above depend on whether asymptomatic infections are common, and protective against future infection. Further, strategies for leveraging protective immunity will depend on the development and validation of assays that can reliably identify individuals who are effectively protected against re-infection. Previous studies have identified numerous asymptomatic infections via IgM and IgG antibody assays1–2, which, while indicative of infection, do not necessarily imply protective immunity5. Evidence for long term protective immunity observed in (symptomatic) EVD survivors is suggestive5, but the extent of protective immunity following asymptomatic infection and the identification of serological markers for protective immunity can only be definitively addressed in settings with ongoing transmission risk. As has been proposed for vaccination6, the current epidemic therefore provides a unique opportunity to investigate asymptomatically acquired protective immunity to EVD. While recognizing that resources are scarce, now is the time for interventions targeted at high-risk groups (i.e., health care workers and household caregivers) to incorporate serological assessments to ascertain asymptomatic infections and immunological correlates of protection.

A more direct investigation of asymptomatically acquired immunity might be possible by leveraging recently proposed trials to assess the efficacy of blood transfusions from EVD survivors as treatment for EVD patients7. A study during the 1995 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo found elevated survival rates in transfusion recipients, but was potentially confounded by the superior supportive care afforded the treated patients8. Burnouf and colleagues7 have advocated for randomised controlled clinical trials comparing the treatment efficacy of transfusions from survivors versus from control donors. By including a third study arm in which patients receive transfusions from asymptomatic seropositive individuals, this design could simultaneously assess the therapeutic value of transfusions from asymptomatic individuals (who are healthier, and may be more numerous than, survivors), and indicate whether such individuals have protective immunity.

In conclusion, estimating the prevalence and immunological consequences of asymptomatic infection is critical to forecasting and may inform public health strategies that leverage natural immunity to mitigate the ongoing outbreak and prevent future epidemics. We propose that launching an immediate investigation of asymptomatic immunity, by coupling serological testing to ongoing intervention efforts in Western Africa, is warranted and feasible, and may ultimately save lives.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Champredon, Stephanie Cinkovich, and Spencer Fox for assistance with reviewing the literature, and Carl Pearson for helpful discussions.

Funding: SEB and LAM were supported by a National Institute of General Medical Sciences MIDAS grant to LAM and Alison P Galvani (U01GM087719). JRCP is supported by the Research and Policy on Infectious Disease Dynamics (RAPIDD) Program of the Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health and Science and Technology Directorate, Department of Homeland Security. SEB and JRCP were additionally supported by the International Clinics on Infectious Disease Dynamics and Data (ICI3D) program, which is funded by a National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health grant (R25GM102149) to JRCP and Alex Welte. JD is supported by the The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). The funding sources played no role in the analysis, interpretation of results, or decision to submit the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: SEB initiated the study concept, reviewed the literature, performed the modeling analysis and wrote the first draft. SEB, JRCP, JD, and LAM contributed to the study design, the interpretation and presentation of results, and the writing and approval of the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Steve E Bellan, Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA.

Juliet RC Pulliam, Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USAEmerging Pathogens Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USAFogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Prof. Jonathan Dushoff, Department of Biology and Institute of Infectious Disease Research, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada.

Prof. Lauren Ancel Meyers, Department of Integrative Biology, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USASanta Fe Institute, Santa Fe, NM, USA.

References

- 1.Heffernan RT, Pambo B, Hatchett RJ, Leman PA, Swanepoel R, Ryder RW. Low seroprevalence of IgG antibodies to Ebola virus in an epidemic zone: Ogooué-Ivindo region, Northeastern Gabon, 1997. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:964–8. doi: 10.1086/427994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leroy E, Baize S, Volchkov V. Human asymptomatic Ebola infection and strong inflammatory response. Lancet. 2000;355:2210–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02405-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Ebola Response Team. Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa - The First 9 Months of the Epidemic and Forward Projections. N Engl J Med. 2014:1–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meltzer MI, Atkins CY, Santibanez S, et al. Estimating the Future Number of Cases in the Ebola Epidemic — Liberia and Sierra Leone, 2014–2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong G, Kobinger GP, Qiu X. Characterization of host immune responses in Ebola virus infections. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10:781–90. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.908705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galvani AP, Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Wenzel N, Childs JE. Ebola Vaccination: If Not Now, When? Ann Intern Med. 2014:9–11. doi: 10.7326/M14-1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnouf T, Emmanuel J, Mbanya D, El-Ekiaby M, Murphy W, et al. Ebola: a call for blood transfusion strategy in sub- Saharan Africa Lancet. 2014;6736:1001309. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61693-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mupapa K, Massamba M, Kibadi K, Kuvula K, Bwaka A, et al. Treatment of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever with Blood Transfusions from Convalescent Patients. 1999;179:18–23. doi: 10.1086/514298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]