Abstract

Veterans are increasingly using complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies to manage chronic pain and other troubling symptoms that significantly impair health and quality of life. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is exploring ways to meet the demand for access to CIH, but little is known about Veterans’ perceptions of the VA’s efforts. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted interviews of 15 inpatients, 8 receiving palliative care, and 15 outpatients receiving CIH in the VA. Pain was the precipitating factor in all participants’ experience. Participants were asked about their experience in the VA and their opinions about which therapies would most benefit other Veterans. Participants reported that massage was well-received and resulted in decreased pain, increased mobility, and decreased opioid use. Major challenges were the high ratio of patients to CIH providers, the difficulty in receiving CIH from fee-based CIH providers outside of the VA, cost issues, and the role of administrative decisions in the uneven deployment of CIH across the VA. If the VA is to meet its goal of offering personalized, proactive, patient-centered care nationwide then it must receive support from Congress while considering Veterans’ goals and concerns to ensure that the expanded provision of CIH improves outcomes.

Keywords: access, complementary and alternative medicine, cost, inpatients, integrative health, massage therapy, mobility, opioid use, outpatient, pain, patient to provider ratio, patient-centered care, Veterans

INTRODUCTION

Like millions of Americans, Veterans are using complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies such as massage and acupuncture and/or practicing CIH self-care activities like yoga, Qigong, Tai Chi, and meditation [1]. The Veteran’s goal is to find new approaches to managing and/or rehabilitating from chronic pain, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other troubling symptoms, which significantly affect health and quality of life. Research on many of these therapies has shown promising results [2–8]. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is exploring ways to meet this demand for access to CIH when combined with conventional medical care. In 2010, the VA created the Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation. Included in the office’s responsibilities is the promotion of CIH within the VA through the recent establishment of an Integrated Health Coordinating Center [9].

Although there is increasing research about the use of CIH therapies in the VA [10–17], less is known about how Veterans perceive these therapies. In a study of 401 Veterans with non-cancer-related chronic pain, Denneson et al. found that 96.8 percent were willing to try massage therapy [1]. We theorized that patients whom we were studying quantitatively related to massage therapy might also be open to discussing other CIH therapies. The purpose of this qualitative portion of our study was to examine the experience, knowledge, and opinions of Veterans receiving massage therapy at a large VA facility regarding massage therapy in particular and CIH therapies in general.

METHODS

We conducted a mixed-methods pilot study at one VA site as part of a study funded by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine of the National Institutes of Health. The aim of a supplement to the parent study was promotion of a collaboration between a non-VA hospital with an extensive CIH program and a VA hospital for the purpose of promoting CIH at the VA site [18–19]. To better understand how CIH was currently viewed at the VA, our approach included interviews of VA patients, providers, and administrators about the use of CIH.

Participants

The results of the interviews with providers and administrators have been previously published [20]. For the portion of the study reported here, a convenience sample of 30 participants was recruited for qualitative interviews, including 15 inpatients and 15 outpatients. The inpatients were approached by the research assistant regarding study participation prior to receiving a therapeutic massage. The outpatients were approached when they came for their massage appointments. For some inpatients, the interview occurred at the time of their first massage. All participants were receiving or had received therapeutic massage at the VA as part of their treatment for chronic pain or as part of their palliative care including pain relief.

Data Collection

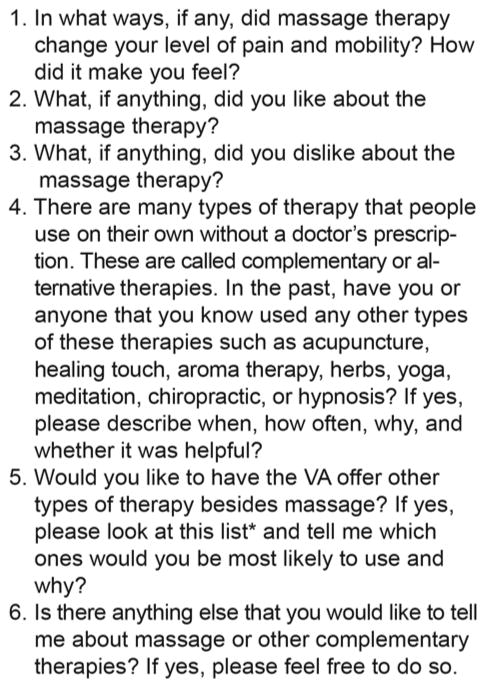

During the study period, the therapist received 129 referrals from VA providers for provision of therapeutic massage services. Of the 84 inpatient referrals, 65 were on the palliative care service. Of the 45 outpatient referrals, 23 were receiving palliative care and 22 were primary care patients diagnosed with a chronic pain condition. From these referrals, 15 inpatients (based on willingness and ability to communicate; many were too ill) and 15 outpatients (based on willingness and availability to participate) were interviewed. Subjects described their experience with CIH therapies (including those services experienced outside of the VA) in general and with massage in particular, their views about the use of CIH in the VA, and their opinions about which CIH therapies would be most acceptable and/or useful to Veterans. After the participant signed an informed consent form, interviews were conducted and digitally recorded in a private location by one member of the research team (C.E.F.) between May 2013 and May 2014. All participants were asked the same open-ended questions (Figure 1), which focused on massage because having received a therapeutic massage was the common denominator in this sample. However, participants were encouraged to discuss use of other CIH therapies as well. Length of the interview ranged from 3:02 to 19:15 min for inpatients and from 7:58 to 29:19 min for outpatients depending on participant responses.

Figure 1.

Interview questions for patients. *List of some of more common complementary and integrative health therapies. VA = Department of Veterans Affairs.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by one team member (E.L.T.). Because the interviewer was familiar with the content of all of the interviews, she developed a list of initial codes to start the review process. Three team members with qualitative experience then individually coded all of the interviews and a fourth team member coded four of them. Using content analysis, the team then met as a group to collaboratively confirm codes and categories [21] using NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd; Doncaster, Australia). Emerging themes in the data were identified through extensive discussion and thematic analysis. As new categories emerged, coding was focused and additional codes and subcodes were developed until all reviewers agreed that the essence of the interviews had been captured [21].

RESULTS

The majority of the inpatients was on the palliative care service, male, Caucasian, and age ≥61 yr (average age: 62.3 yr). All outpatients were ambulatory and receiving therapeutic massages to relieve chronic pain. Although one outpatient had been given <1 yr to live due to cancer, the others had no known terminal illnesses. As with the inpatients, most outpatients were Caucasian males evenly divided between ages 41 to 60 and ≥61 yr. Table 1 summarizes the participant demographics. The participants’ responses reported next are categorized under the general headings of experience, knowledge, and opinions.

Table 1.

Demographics of interviewed patient population. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

| Demographic | Inpatient (n = 15) | Outpatient (n = 15) | Total (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr)* | 62.3 ± 11.9 | 61.0 ± 8.9 | 61.6 ± 10.4 |

| ≤40 | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| 41–60 | 4 (27) | 7 (47) | 11 (37) |

| ≥61 | 10 (67) | 8 (53) | 18 (60) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 14 (93) | 13 (87) | 27 (90) |

| Female | 1 (7) | 2 (13) | 3 (10) |

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 13 (87) | 15 (100) | 28 (93) |

| African American | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | 2 (7) |

| Referring Service† | |||

| Palliative Care | 8 (53) | 1 (7) | 9 (30) |

| Manual Medicine | 3 (20) | 11 (73) | 14 (47) |

| Pain Clinic | 2 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (13) |

| Rehabilitation | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Inpatient Medicine | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Using Opioids* | 12 (80) | 9 (60) | 21 (70) |

At time of study enrollment.

Medical records of one outpatient contained no information about service referring to massage therapy but participant was likely referred by family member.

Experience

With Other Complementary and Integrative Health Therapies

Although the common factor among participants was their experience with therapeutic massage provided in the VA, they had used a wide range of other CIH therapies as well, both within and outside of the VA. After being shown a list of common CIH therapies to stimulate their thinking, each of the participants was asked two questions regarding what CIH therapy or therapies they had personally used and what CIH therapies they would recommend for the VA to promote or initiate for Veterans in general (Figure 1). Participants’ answers included not only the therapies on the list but also items such as transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation units that are not necessarily considered CIH therapy but that the respondent thought should be included in the grouping. Their personal experiences with CIH were also not necessarily formal but nonetheless informed the participants’ definitions of CIH. For instance, when asked whether he practiced meditation one participant stated, “Yes, because you can do a lot of thinking when you are fishing.” As it turned out, the outpatients had experienced a broader range of therapies. All (n = 15) had experienced therapeutic massage followed by manual manipulation (osteopathic manipulative treatment available at this particular VA) (n = 10), diet/herbal (n = 9), pet therapy (n = 9), meditation (n = 8), and chiropractic (n = 8). On the inpatient side, all but one participant had experienced therapeutic massage (n = 14), followed by meditation (n = 6), chiropractic (n = 5), and pet therapy (n = 5).

Pain

Pain was the common factor precipitating use of CIH in all of the participants’ experiences. Pain experienced by outpatients was largely musculoskeletal, occurring in the back, neck, shoulders, hips, and knees. One participant explained, “The pain level sometimes is so distracting that it debilitates you to the point you cannot function or think straight.” Almost all participants described at least a temporarily significant reduction in their level of pain. Massage was described as “taking the edge off,” helping manage and mitigate pain. “It doesn’t make it go away permanently but it does make you feel better for a while, which when you are in pain all the time is a big thing.”

Both inpatients and outpatients reported a decrease in pain from 1 to 3 points on a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale, which is consistent with the scientific literature of CIH on pain for civilian inpatients [18–19]. Reported pain changes were comparable across groups, with the exception that inpatients reported a shorter duration of pain relief than outpatients. This difference may have been due to the causes of inpatient pain, e.g., radiation-induced oral mucositis or pressure from expanding soft tissue tumors. Although a palliative care patient stated that massage did nothing for his pain, he did report that massage calmed him down, an important effect regarding anxiety control. Another described the relief as temporary, adding, “It’s too bad that it’s not permanent, but it does give me an amount of relief.” Another appreciated that it made him feel “real good” even though simply swallowing liquids made the pain start “shooting back.” And another described the massage as getting rid of his back pain “a little bit,” but then added, “I enjoyed it; that’s for damn sure.”

Some outpatients reported a longer-term reduction in pain than inpatients, anything from days to weeks to indefinite relief. A Veteran who now walks independently described being weaned off fentanyl through the combined efforts of a pharmacist, manual medicine provider, and massage therapist. Another stated, “I’d still be walking with a cane and wearing a back brace.” A third said he had been able to stop using a walker for the past 2 to 3 yr. All of these participants attributed their improvement to the effects of therapeutic massage.

Massage

Participants reported an overwhelmingly positive response to the therapeutic massages, chiefly as a way to relieve pain but also to increase mobility and flexibility; promote relaxation; foster more restful sleep; and reduce anxiety, stress, depression, and fatigue. Some participants reported an initial increase in pain associated with the depth of the massage, but all felt the end result justified the experience. “She really works my muscles and it’s painful, but I always feel better before leaving.”

Access

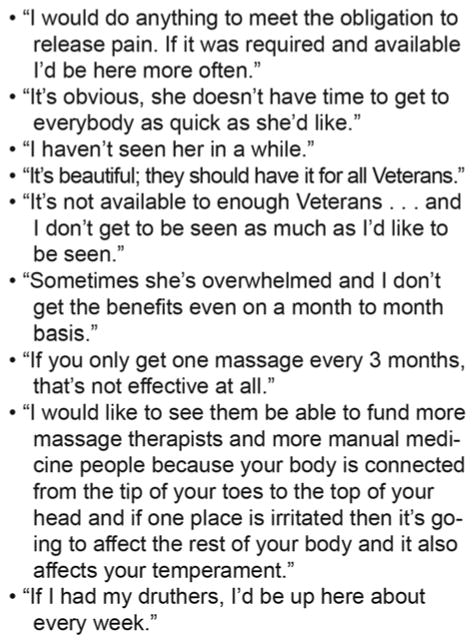

Participants described several separate but interrelated problems regarding access to CIH services. A primary concern was the ratio of providers to patients. This particular VA facility has one massage therapist on staff (almost all other VA hospitals do not have any massage therapists) and one manual medicine practitioner. However, the demand for their services far outstrips what these two providers can provide. As a result, only a limited number of outpatients are offered therapeutic massages or manual manipulation, and most are only seen once a month unless they have an acute flair-up of pain. Most inpatients offered therapeutic massage are those who are on palliative care service. At most, these patients receive a massage two or three times a week (Figure 2). Two palliative care patients wished for daily massages: “As they pass the meds out, pass me a massage.” But as one participant observed, “Without somebody listening in Congress or the VA you’re not gonna get another [therapist].”

Figure 2.

Patient quotes related to access to complementary and integrative health.

A second issue involved the fact that many Veterans live ≥1 h driving time away from the VA medical center (an issue frequently found at other VA medical centers as well). “I’m 4 hours away.” “I drive 80 miles [one way] to have this done and if it wasn’t worthwhile I sure wouldn’t make the trip.” In response, the VA offers “fee-based” visits that allow Veterans to receive therapy in the local community provided by a non-VA provider. Although this sounds like a viable, if temporary, solution, participants cited problems here, too:

I would have liked to have had more, but I guess it was a long, drawn out process, and I don’t know why it stopped. I went and I filled out all the paperwork and it stopped, and I had to fill out paperwork again. He said it only goes for so long, and I was hoping to get some more extensive, but I don’t know if I can do it here or it’s more feasible for them to do it outside.

When asked about the paperwork involved to see a fee-based acupuncturist, a participant described it as, “Very, very complicated. There’s a lot of paperwork and just running around.” The participant eventually received acupuncture for a year, but then his primary care provider had to reauthorize further treatment.

Cost was a third issue affecting access. Because therapies such as yoga, Tai Chi, and acupuncture are not offered at the VA in which this study was conducted, participants reported having to use these therapies on their own. Referring to outside classes in Qigong and Tai Chi, a participant stated he did so only when he could afford it. A second stated he received CIH at the VA that day because a fee-basis authorization for acupuncture he received last year was not found. Another participant with PTSD who works with other Veterans with PTSD reported he has advised them to get massages, but, “Some of them were quite irritated that it was either not available or having to go to an outside source. Some of them were actually paying out of their own pockets because VA’s not covering [the massage].”

Veteran-Specific Challenges

Service-connected conditions or situations were part of participants’ conversations, whether discussing CIH or not. Participants associated being in the service as a specific cause of their pain and need for CIH but also described the “aftereffects of being in the service” on their lives in general. One long-term massage recipient described guarding large drums on piers without knowing the contents. He was now questioning whether they contained chemicals such as Agent Orange. Another described being exposed to extremely loud noises without adequate hearing protection. He concluded, “I’m very suspicious and not very trusting because of that. . . . It takes a long time for somebody to ever become really close to me. . . . My wife’s put up with an awful lot of [expletive].” Their ongoing relationship with and trust in the therapist appeared to allow them to express these concerns.

Knowledge: Opioids and Complementary and Integrative Health

Even though 60 percent of the outpatients were currently taking opioids for pain relief (Table 1), they were particularly aware of problems associated with opioid use. One participant stated he was able to reduce his use of the pain medication Vicodin (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) due to receiving massage. Another participant cautioned against getting “hooked” on opioids. A third observed that pain medications do effectively control pain, “but they make you feel worse in the long run.” Yet another opined that having another therapy to offer Veterans before giving an addictive drug was “a tremendous idea.” A fellow participant agreed that using massage instead of medication would be a lot better for PTSD or other types of depression and stress. The high cost of medications was the focus of another participant: “It’s not good to have to take all of these drugs all the time and then have to keep track of them and get them reordered. It costs the government a lot of money. You might be able to eliminate a lot of that,” implying CIH should be used more. Only one participant, an inpatient, made light of his drug use, stating he was eager to return home to an unlimited (illegal) supply of his drugs of choice.

Opinions

Complementary and Integrative Health Therapist

Praise for the massage therapist was overwhelmingly positive. While both inpatients and outpatients appreciated the massage itself, the outpatients particularly appreciated the additional lifestyle coaching and encouragement that the therapist provided. It was evident that the therapist’s approach played an important part in the therapy.

Importance of Veteran Education and Relationships in Promoting Complementary and Integrative Health

One participant expressed a need for Veterans to be educated about massage. He illustrated his recommendations by describing Veterans as being “bad about relaxing” and considering massage as a waste of time “like a pedicure.” Others emphasized the importance of the bond between Veterans when asked whether Veterans would accept CIH therapies. A participant thought that if a Veteran was approached by another Veteran who had experienced the CIH therapy, he or she would be much more accepting of CIH. Another stated that Veterans are “bad” about the thought of someone touching them, so they need to be educated about massage. When describing the chance for Veterans to talk with other Veterans during a VA wellness group, a participant opined that Veterans need to talk with someone “who has walked in their shoes” as opposed to a clinician who has “just read about it.” Another said, “I can deal with it on a totally different level and that’s important to a Veteran who has been through the wringer.” A participant described CIH therapies that are promoted in the group as “very appealing” to Veterans. Another participant thought that CIH therapies “would probably be the best medicine” for PTSD, while another stated 4 out of 12 Veterans in his PTSD group were using CIH therapies. When describing how fellow Veterans had helped to calm a young Veteran who was crying in pain, a participant stated, “GIs have an interesting bond on each other, a lot of trust, a lot of respect, a lot of understanding.”

Recommended Complementary and Integrative Health Therapies for Veterans

When asked to name the CIH therapies participants thought would appeal most to Veterans, inpatients chose massage, chiropractic, and music therapy while outpatients listed massage, yoga, acupuncture, and chiropractic therapy (Tables 2–3). Participants had not necessarily experienced a CIH therapy before recommending it. For instance, none of the inpatients had previously tried Reiki, aromatherapy, Qigong, touch therapy, or biofeedback, but one person recommended that each of those therapies be used in the VA. Two of the inpatients did not feel comfortable recommending any of the CIH therapies. One stated that people from small towns like the one from which he came call people who use these types of therapies “Beverly Hillbillies,” implying they try to act sophisticated when they are not.

Table 2.

Outpatient experiences with and recommendations for complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies for Veterans (n = 15).

| CIH Therapy | Used | Recommended |

|---|---|---|

| Massage* | 15 | 13 |

| Manual Manipulation*† | 10 | 4 |

| Diet/Herbal | 9 | 2 |

| Pet Therapy* | 9 | 2 |

| Meditation | 8 | — |

| Chiropractic | 8 | 6 |

| Aroma* | 7 | — |

| Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Unit*‡ | 7 | 1 |

| Acupuncture | 6 | 7 |

| Music* | 6 | — |

| Biofeedback | 6 | 5 |

| Yoga | 4 | 8 |

| Qigong | 3 | — |

| Hypnosis | 2 | 3 |

| Touch | 2 | — |

| Tai Chi | 2 | 1 |

| Reiki | 1 | 1 |

| Mantram Repetition | 1 | — |

Offered at study Department of Veterans Affairs medical center.

Osteopathic manipulative treatment for musculoskeletal pain and disability.

Therapeutic device used to stimulate nerves. It sends electrical pulses to surface of skin via electrodes that stimulate nerves.

Table 3.

Inpatient experiences with and recommendations for complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies for Veterans (n = 15).

| CIH Therapy | Used | Recommended |

|---|---|---|

| Massage* | 14 | 10 |

| Meditation | 6 | 1 |

| Chiropractic | 5 | 5 |

| Pet Therapy* | 5 | 4 |

| Music* | 3 | 5 |

| Yoga | 2 | 4 |

| Hypnosis | 2 | 3 |

| Diet/Herbal | 2 | 3 |

| Aroma* | 2 | 1 |

| Marijuana | 2 | — |

| Acupuncture | 1 | 3 |

| Water Aerobics | 1 | — |

| Reiki | — | 1 |

| Qigong | — | 1 |

| Touch Therapy | — | 1 |

| Biofeedback | — | 1 |

Offered at study Department of Veterans Affairs medical center.

Administrative Decisions

The participants were divided in their attitudes toward VA administration and the decisions that are made regarding funding priorities:

The VA seems to be many, many times more interested in appearing to be concerned with Vets than they actually are being concerned about Vets. . . . Veterans don’t care about the pictures on the wall. They don’t care what color the floor tile is. . . . They seem to waste so much money on appearances that they could be actually putting toward improving treatment . . . the massage therapy, the manipulative medicine.

Another stated that servicemembers had been promised never to be left behind, but that due to the actions of people at both the local and national level, “There’s a lot of Veterans that feel like they’re left behind.” A third stated, “The suits up on the ivory tower, they need to open their minds that there is a whole different universe outside of medical school and pharmaceutical industry pushing their programs.”

However, not every participant agreed. One outpatient who spends a lot of time volunteering at the VA medical center stated that if there was something wrong he could always go to the local administration, which would listen to him and look into the complaint. Another observed, “I know they can’t always satisfy me but I’ll tell ya . . . I have no complaints. . . . They have to weigh the dollars. . . . We can’t keep wasting.” An inpatient also expressed concern that, as much as he enjoyed the massages, funding that was badly needed elsewhere should not be diverted solely for massages.

DISCUSSION

Because of their experiences in the armed forces, Veterans share both a distinctive bond and problems that are unique to them or magnified in prevalence compared with the general population. Chronic pain, estimated at 26 percent in the general population and over 44 percent in Veterans after combat, and illicit prescription opioid use, estimated at 4 percent in the general population and 15 percent after combat deployment, are excellent examples [22]. Hence, it is not surprising that pain was the common experience in this group of Veterans, whether related to a cancer diagnosis or other ailment. However, it is noteworthy especially for the outpatients that 60 percent of outpatients and 80 percent of inpatients were currently using opioids while at the same time recognizing the dangers inherent in continued opioid use. Acknowledging the problem of inappropriate opioid use, the VA recently issued a mandate to reduce the prescription of opioids [23]. The issue for Veterans is that the reduction of opioids without a satisfactory alternative to pain control potentially leaves the Veteran captive to chronic, often debilitating, pain as illustrated by the responses of the study participants, hence the overwhelming need for a nonpharmacologic alternative such as massage to be available on a consistent basis.

It is noteworthy that therapeutic massage appears to control pain severity by its effects on both physical and psychological symptoms, thus contributing to improved physical and mental well-being [13,24–25]. As illustrated by the participants’ overwhelmingly positive responses, not only did they experience relief from physical pain through massage but they also related to the therapist on a personal basis. It was apparent that, in this situation, the physical manipulation of massage was only a part of the therapy offered by the therapist in addition to teaching, coaching, encouragement, and therapeutic listening. Due to long-term contact with many of the participants, the therapist knew and understood them well. Thus, she was able to offer a much broader level of care than might be generally expected. The therapeutic interaction between the massage therapist and the patient transcended the pharmacological effect of opioids binding to receptors.

The type of care offered by the massage therapist is a perfect illustration of the VA’s vision of offering personalized, proactive, patient-centered care. Although stated very differently, both VA administrators and the Veteran participants perceive an unfortunate negative influence of the medical model of care due to its emphasis on diagnosis and treatment as prescribed by the clinician, which may be slowing the acceptance of CIH therapies with their emphasis on what the patient considers important. They also agree that access is an issue, although they see the problem from different perspectives. While VA administrators describe the situation in administrative terms, including lack of position descriptions, inability to capture workload, misunderstanding about benefits, and the need for more evidence to back the use of CIH [20], the Veterans detail the issues immediately apparent to them, including the scarcity of providers, distances they have to travel to receive CIH therapies, and cost of care at least partly due to administrative snarls involving paperwork. However, while the perspectives differ from administrator to Veteran, basically they all agree that while increased access to CIH therapies, particularly massage, meditation, yoga, and acupuncture, is a priority goal, there are major issues of access plus provider and patient knowledge and opinions the VA must address in order to accomplish this goal.

Of note, to better address the problem of access, the VA has recently introduced the concept of Choice Cards, an option designed to allow Veterans to seek care outside of the VA if they cannot receive care within the VA in a timely manner. Beginning November 17, 2014, the VA began mailing the cards to Veterans waiting more than 30 d for an appointment at a VA facility. The VA then added an option that Veterans living more than 40 mi from a VA facility could also seek outside care. Whether these options will eliminate the problems for access to CIH described by the study participants remains to be seen.

A perhaps unexpected thread that came out of the participants’ comments was the awareness of cost issues. While some criticized the VA for spending money on facilities rather than care, others expressed awareness that the VA needs to meet many priorities when making funding decisions. Several were also altruistic when considering their fellow Veterans, expressing concern that as beneficial as CIH is, money may be needed even more to provide basic medical care. The participants demonstrated awareness of the needs of other Veterans as well as themselves, reflecting the “no Veteran left behind” motto that is inculcated into servicemembers.

Interpretation of the findings of this study is limited by basing it on a convenience sample of Veterans receiving care from one massage therapist at only one VA facility. Although the Veterans were both inpatients and outpatients with a variety of diagnoses, they were primarily being treated due to chronic pain or the need for palliative care. A broader subject pool, e.g., users in pain due to other diagnoses, would have enhanced the findings and could be the subject of future research endeavors. Because subjects were already receiving one type of CIH therapy (therapeutic massage), their experience may have influenced the views they expressed regarding massage and/or other CIH therapies. However, the findings from the current study mesh with our previous study involving providers and administrators at the local level [20].

CONCLUSIONS

CIH therapies such as therapeutic massage offer a complementary form of therapy and/or rehabilitation that can reduce or sometimes eliminate opioid use for chronic pain. Although the promotion of CIH is important to the VA, the willingness of Veterans to use these therapies or the barriers to their use by otherwise willing Veterans need more attention. Furthermore, the willingness of Congress to fund such therapies in a contentious political climate is an important variable. As the VA goes forward with plans to reduce opioid use while promoting personalized, proactive, patient-centered care, e.g., through the use of CIH, it is essential to continue listening to what Veterans consider to be important goals as well as the obstacles to reaching those goals. It will also be important to evaluate the extent to which CIH therapies can improve clinical outcomes and result in cost savings to the VA and to educate and cultivate champions for their use in Congress.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This material was based on work supported by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health (grant R01AT006518).

Abbreviations

- CIH

complementary and integrative health

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- VA

Department of Veterans Affairs

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Institutional Review: Approval for the study was obtained from the Ann Arbor VA Human Studies Committee prior to interviews.

Participant Follow-up: Participants will be contacted informally about the publication of this study by the massage therapist if she continues to treat a patient interviewed for this study.

Author Contributions:

Study concept and design: C. E. Fletcher, A. R. Mitchinson, E. L. Trumble, J. A. Dusek.

Acquisition of data: C. E. Fletcher, A. R. Mitchinson, E. L. Trumble.

Analysis and interpretation of data: C. E. Fletcher, A. R. Mitchinson, E. L. Trumble, D. B. Hinshaw.

Drafting of manuscript: C. E. Fletcher, A. R. Mitchinson, E. L. Trumble, D. B. Hinshaw.

Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: C. E. Fletcher, A. R. Mitchinson, E. L. Trumble, D. B. Hinshaw, J. A. Dusek.

Obtained funding: J. A. Dusek.

Study supervision: C. E. Fletcher, J. A. Dusek.

References

- 1.Denneson LM, Corson K, Dobscha SK. Complementary and alternative medicine use among veterans with chronic noncancer pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(9):1119–28. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2010.12.0243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2010.12.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coeytaux RR, McDuffie J, Goode A, Cassel S, Porter WD, Sharma P, Meleth S, Minnella H, Nagi A, Williams JW., Jr . VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014. Evidence map of yoga for high-impact conditions affecting veterans. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford C, Lee C, Buckenmaier C, 3rd, Schoomaker E, Petri R, Jonas W Active Self-Care Therapies for Pain (PACT) Working Group. The current state of the science for active self-care complementary and integrative medicine therapies in the management of chronic pain symptoms: Lessons learned, directions for the future. Pain Med. 2014;15(Suppl 1):S104–13. doi: 10.1111/pme.12406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pme.12406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawford C, Lee C, May T Active Self-Care Therapies for Pain (PACT) Working Group. Physically oriented therapies for the self-management of chronic pain symptoms. Pain Med. 2014;15(Suppl 1):S54–65. doi: 10.1111/pme.12410. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pme.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hempel S, Taylor SL, Solloway MR, Miake-Lye IM, Beroes JM, Shanman R, Booth MJ, Siroka AM, Shekelle PG. VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014. Evidence map of acupuncture. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hempel S, Taylor SL, Marshall NJ, Miake-Lye IM, Beroes JM, Shanman R, Solloway MR, Shekelle PG. VA Evidence-Based Synthesis Program Reports. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs; 2014. Evidence map of mindfulness. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherman KJ, Cook AJ, Wellman RD, Hawkes RJ, Kahn JR, Deyo RA, Cherkin DC. Five-week outcomes from a dosing trial of therapeutic massage for chronic neck pain. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):112–20. doi: 10.1370/afm.1602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1370/afm.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan G, Craine MH, Bair MJ, Garcia MK, Giordano J, Jensen MP, McDonald SM, Patterson D, Sherman RA, Williams W, Tsao JC. Efficacy of selected complementary and alternative medicine interventions for chronic pain. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(2):195–222. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2006.06.0063. http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2006.06.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole health: The vision and implementation of personalized, proactive, patient-driven health care for veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S5–8. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bormann JE, Hurst S, Kelly A. Responses to Mantram Repetition Program from Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative analysis. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2013;50(6):769–84. doi: 10.1682/JRRD.2012.06.0118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2012.06.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collinge W, Kahn J, Soltysik R. Promoting reintegration of National Guard veterans and their partners using a self-directed program of integrative therapies: A pilot study. Mil Med. 2012;177(12):1477–85. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-12-00121. http://dx.doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-12-00121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ezeji-Okoye SC, Kotar TM, Smeeding SJ. State of care: Complementary and alternative medicine in Veterans Health Administration—2011 survey results. Fed Pract. 2013;30:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchinson A, Fletcher CE, Kim HM, Montagnini M, Hinshaw DB. Integrating massage therapy within the palliative care of veterans with advanced illnesses: An outcome study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(1):6–12. doi: 10.1177/1049909113476568. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049909113476568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bent K, Hemphill L. Use of complementary and alternative therapies among veterans: A pilot study. Fed Pract. 2004;21(10):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Libby DJ, Pilver CE, Desai R. Complementary and alternative medicine in VA specialized PTSD treatment programs. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(11):1134–36. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinhard MJ, Nassif TH, Bloeser K, Dursa EK, Barth SK, Benetato B, Schneiderman A. CAM utilization among OEF/OIF veterans: Findings from the National Health Study for a New Generation of US Veterans. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S45–49. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000229. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smeeding S, Osguthorpe S. The development of an integrative healthcare model in the Salt Lake City Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11(6):46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson JR, Crespin DJ, Griffin KH, Finch MD, Dusek JA. Effects of integrative medicine on pain and anxiety among oncology inpatients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2014;2014(50):330–37. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson JR, Crespin DJ, Griffin KH, Finch MD, Rivard RL, Baechler CJ, Dusek JA. The effectiveness of integrative medicine interventions on pain and anxiety in cardiovascular inpatients: A practice-based research evaluation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:486. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-486. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fletcher CE, Mitchinson AR, Trumble EL, Hinshaw DB, Dusek JA. Perceptions of providers and administrators in the Veterans Health Administration regarding complementary and alternative medicine. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S91–96. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonas WB, Schoomaker EB. Pain and opioids in the military: We must do better. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1402–3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becker W. Turning the time of chronic opioid therapy [Internet] Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development; 2014. Jun 3, Available from: http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=797. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keir ST. Effect of massage therapy on stress levels and quality of life in brain tumor patients—Observations from a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(5):711–15. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1032-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-1032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchinson AR, Kim HM, Rosenberg JM, Geisser M, Kirsh M, Cikrit D, Hinshaw DB. Acute postoperative pain management using massage as an adjuvant therapy: A randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2007;142(12):1158–67. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1158. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.142.12.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]