Abstract

Purpose

Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse has been shown to lead to increased odds of sexual behaviors that lead to sexually transmitted infections and early pregnancy involvement. Research, meta-analyses, and interventions, however, have focused primarily on girls and young women who have experienced abuse, yet some adolescent boys are also sexually abused. We performed a meta-analysis of the existing studies to assess the magnitudes of the link between a history of sexual abuse and each of three risky sexual behaviors among adolescent boys in North America.

Methods

The three outcomes were a) unprotected sexual intercourse, b) multiple sexual partners, and c) pregnancy involvement. Weighted mean effect sizes were computed from 10 independent samples, from nine studies published between 1990 and 2011.

Results

Sexually abused boys were significantly more likely than non-abused boys to report all three risky sexual behaviors. Weighted mean odds ratios were 1.91 for unprotected intercourse, 2.91 for multiple sexual partners, and 4.81 for pregnancy involvement.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that childhood and adolescent sexual abuse can substantially Influence sexual behavior in adolescence among male survivors. To improve sexual health for all adolescents, even young men, we should strengthen sexual abuse prevention initiatives, raise awareness about male sexual abuse survivors’ existence and sexual health issues, improve sexual health promotion for abused young men, and screen all people, regardless of gender, for a history of sexual abuse.

Keywords: meta-analysis, sexual abuse, risky sexual behavior, teen pregnancy, adolescent, males

Introduction

Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse has received attention in various areas of research, practice, and public policy because of its deleterious effects on victims’ lives. Accumulated evidence shows the association between a history of sexual abuse and decreased psychological well-being such as depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidality [1]. On average, about 20% of females and 8% of males in North America report a history of sexual abuse [2]. Although prevalence estimates vary by definitions of sexual abuse, i.e., the type of abuse behavior, a perpetrator-victim age difference, upper limit of victim’s age when abuse occurred [2], as well as sampling characteristics (substantiated cases from police or child welfare agencies vs. self-report in population studies), a substantial number of people have been affected by abuse.

Developmental traumatology argues that overwhelming and chronic interpersonal stress in childhood, including sexual abuse, can lead to alterations in biological stress response systems and affect brain maturation, which in turn can affect psychosocial and cognitive development [3]. Those with sexual abuse histories during childhood or adolescence often have difficulties developing quality interpersonal relationships and social ties. Sexual abuse, particularly by family members or someone known to the victim, violates his or her most intimate boundaries and trust [4], which can lead to distrust of others, low self-disclosure, and social isolation. Some victims may avoid relationships with others out of fear of re-victimization; others may demonstrate extreme needs for closeness and inappropriate self-disclosure [5]. Cognitive impairments from sexual abuse can include overestimating the amount of adversity in current environments, and victims underestimating their self-efficacy and self-worth as a result of their perception that the world is dangerous, and exacerbating a sense of powerlessness [5].

The neurobiological dysregulation from sexual abuse and its effects on psychosocial and cognitive development can also lead to risky sexual behaviors. A sense of powerlessness and low self-esteem created by the abuse experience, and low assertiveness associated with depression, can affect one’s ability to negotiate contraceptive or protective barrier use [4] and to form and maintain secure interpersonal relationships [5]. Sex may become a means for securing affection and intimacy, potentially leading to earlier sexual debut [6], or altered cognitions after sexual abuse may lead victims to appraise risky sexual behaviors more positively [7]. Abuse victims’ relationship difficulties may manifest as involvement in multiple or superficial sexual partnerships [8]. To alleviate their suffering from the traumatic experiences and to enhance self-esteem, those with a history of childhood or adolescent sexual abuse may use substances as a coping strategy. Substance use is associated with risky sexual behaviors [9]. Sexually abused individuals addicted to substances may exchange sex for money or drugs to support their drug dependence.

Studies have shown that a history of childhood or adolescent sexual abuse is associated with unprotected sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, early sexual initiation, teen pregnancy involvement, and exchange of sex for money or drugs. The majority of these studies, however, have been focused on females. A meta-analysis of 46 studies of adult women reported statistically significant but small effects of sexual abuse on HIV risk behaviors; mean effect sizes were r = 0.05 for unprotected sexual intercourse and 0.13 for multiple sexual partners [10]. Another meta-analysis reported a mean effect size (d) of 0.29 for sexual promiscuity, defined as early involvement in sexual activity and prostitution [1]. In a meta-analysis of 21 studies, women who experienced sexual abuse were 2.2 times more likely than those without an abuse history to report pregnancy during adolescence [11].

Prevalence rates of reported sexual abuse are generally lower among men than among women [2]. Boys are less likely than girls to report sexual abuse during childhood and adolescence, however, the actual prevalence of abuse among males may be underestimated due to potential underreporting [12]. Culturally prescribed gender expectations may make boys reluctant to report sexual abuse, or to identify their experience as abuse [4]. Boys are socialized to be competent and autonomous in interpersonal relationships [13] and are expected to take the lead in sexual relationships [4]. The cultural norms of masculinity may make sexually abused boys feel that they failed to live up to these norms, and thus they may hesitate to disclose abuse experiences. Besides stigma associated with sexual abuse, sexually abused boys face social stigma related to same-gender sexual activity, because as many as half or more of perpetrators are men (53–94%), even for male victims [12, 14]. These multiple social stigmas may inhibit boys from reporting sexual abuse.

The lower prevalence of reported child and adolescent sexual abuse among men may contribute to less attention to male experiences of such abuse. The lack of awareness may have created and reinforced a brief that sexual abuse is not an issue among boys, and that consequences are not as severe [12]. The limited literature that includes boys and girls suggests that this is far from the case. In a study that used statewide school-based surveys [4], the odds of risky sexual behaviors among sexually abused boys tended to be higher than those among girls. Another study of a regional student survey found that the odds of having multiple sexual partners were higher for sexually abused boys than for their female peers, whereas the odds of unprotected intercourse and pregnancy involvement were similar between genders [15]. However, a limited number of studies have included males or focused on males, and the effects of sexual abuse on their sexual behaviors. To date, there have been no meta-analyses of these effects for males, only for females.

Therefore, the current study focused on childhood or adolescent sexual abuse among males. Risky sexual behaviors were chosen as the outcome because they can cause long-term, serious health problems such as sexually transmitted infections including HIV. Past research, although limited, has consistently shown statistically significant associations between sexual abuse and risky sexual behavior among males, but without a meta-analysis, we do not know the magnitude of this association. The purpose of this meta-analysis study was to examine the association between a history of child or adolescent sexual abuse and risky sexual behaviors among adolescent males in North America.

Methods

Selection of Primary Studies

We conducted computer-based literature searches through Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science using relevant key terms such as sexual abuse, sexual offenses, pregnancy, unsafe sex, sexual partners, condoms, and contraceptive behavior. We limited our searches to studies that were published between 1990 and 2011 and written in English. Other inclusion criteria were: a) findings reported separately for male samples, b) associations reported between a history of sexual abuse experienced in childhood or adolescence and at least one of the following variables: unprotected sexual intercourse, pregnancy involvement as an indicator of unprotected intercourse, or having multiple sexual partners, and c) conducted in North America because Canada and the United States generally share similar socio-cultural beliefs and laws about behavior that constitutes sexual abuse. We also manually searched review articles and reference lists of relevant papers. Sexual abuse was defined by the authors of the primary studies. The definition thus varied from study to study, ranging from including non-contact abuse to being limited to penetrative abuse only. Some authors specified an age difference between victim and perpetrator (e.g., abused by a person who was at least five years older); others did not.

Of 844 articles yielded by these searches, 33 articles met our criteria, including 13 for adolescents in school, 19 for community or clinical samples of adults aged 18, and one clinical sample of adolescents and young adults. We included only studies of adolescents in school for several reasons. First, studies of adolescents were relatively homogeneous in study and sample characteristics. All were cross-sectional school surveys, and all but one study [16] employed probability sampling methods, as opposed to convenience samples in the majority of adult studies. Second, the magnitude of the effects may differ between adolescents and adults due to the difference in the duration of the interval between abuse experiences and subsequent sexual behavior. Third, 15 of adult studies exclusively focused on gay or bisexual men or men who had sex with men, who are generally at higher risk of sexual abuse [13]. Combining this adult subgroup with general student samples may make it difficult to interpret the results of any comparisons between youth samples and adult sample.

Of adolescent studies, two used the 1989 Minnesota Student Survey (MSS), a statewide census survey of 9th and 12th graders [17, 18], and one analyzed two cohorts of the MSS (1992 and 1998) [4]. To ensure independence of data, we excluded older data [17, 18]. Likewise, we included a study of the entire sample from the 2003 British Columbia Adolescent Health Survey [19], and excluded two articles [20, 21] that analyzed a subsample of Aboriginal teens from the same survey. Consequently, nine articles were analyzed in the current study, with 10 independent data sources [4, 15, 16, 19, 22–26].

Data Extraction and Analysis of Effect Sizes

Two of the authors independently coded the primary studies. The following data were abstracted: a) study design, b) sampling methods, c) age or grade range, d) data collection methods, and e) definition of sexual abuse. The same coders extracted data to compute effect sizes. Discrepancies between coders were resolved by review of the original study and discussion, with the help of a third reviewer.

We abstracted one effect size per outcome from each primary study, with one exception [4]. Since this study used two independent datasets, two effect sizes per outcome were obtained. We used an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) to express the effect size. To compute a mean OR, studies were weighted according to the inverse of variance with a fixed-effect model [27]. More weight was thus assigned to studies that generated a more precise estimate, usually as a result of larger sample size. We selected a fixed-effect model because a reliable estimate of the between-studies variance, which is necessary for a random-effects model, cannot be obtained from a small number of studies [27]. The weighted mean effect sizes were computed separately for each of three outcomes; unprotected sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, and pregnancy involvement. The final sample of 10 independent datasets generated 21 effect sizes, with seven for unprotected intercourse, six for multiple sexual partners, and eight for pregnancy involvement. Summary information on the primary studies is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary Information on Studies Included in the Meta-analysis

| Study | Grade | N (% sexually active) | Definition of SA

|

% SA | Outcome (time frame) | OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| behavior | time frame | perpetrator | ||||||

| Chandy et al. (1997) | 7–12 | 740a (55) | C | L | anyone | 50.0 | inconsistent contraception use | 1.17 |

| pregnancy (L) | 3.22 | |||||||

| Howard et al. (2005) | 9–12 | 2982 (100) | FSI | L | anyone | 9.0 | condom nonuse (last sex) | 2.21 |

| 2+ sex partners (3M) | 4.46 | |||||||

| Nagy et al. (1994) | 8, 10 | 514 (100) | FSI | L | anyone | 18.9 | pregnancy (L) | 3.33 |

| Nelson et al. (1994) | 9–12 | 1,139b (49) | C | PY | anyone | 3.4 | 3+ sex partners (L) | 8.02 |

| pregnancy (L) | 13.60 | |||||||

| Pierre et al. (1998) | 9–12 | 795 (100) | C | L | anyone | 8.1 | pregnancy (L) | 5.37 |

| Raj et al. (2000) | 9–12 | 831 (100) | C | L | anyone | 9.3 | condom nonuse (last sex) | 1.54 |

| 3+ sex partners (L) | 4.19 | |||||||

| pregnancy (L) | 5.31 | |||||||

| Saewyc et al. (2004) | 9, 12 | 15,446 (100) | C | L | adult or older | 5.9 | condom nonuse (last sex) | 1.65 |

| 1992 data | 2+ sex partners (PY) | 2.32 | ||||||

| pregnancy (L) | 5.43 | |||||||

| Saewyc et al. (2004) | 9, 12 | 12,843 (100) | C | L | adult or older | 8.8 | condom nonuse (last sex) | 2.25 |

| 1998 data | 2+ sex partners (PY) | 3.08 | ||||||

| pregnancy (L) | 4.19 | |||||||

| Saewyc et al. (2008) | 7–12 | 3,442 (100) | C | L | anyone | 9.1 | condom nonuse (last sex) | 1.98 |

| 3+ sex partners (L) | 2.86 | |||||||

| pregnancy (L) | 4.39 | |||||||

| Shrier et al. (1998) | 8–12 | 3,953 (100) | FSI | L | anyone | 9.9 | condom nonuse (last sex) | 2.09 |

Note. SA = sexual abuse; OR = odds ratio; C = any sexual contact (or non-contact); FSI = forced sexual intercourse; L = lifetime, 3M = past 3 months, PY = past year

In total, 370 (2.2%) boys who participated in the survey reported a history of sexual abuse; an equal number of male participants (n = 370) were randomly selected and matched for age, from non-abused group in order to compare with the abused group.

The sample consisted of boys who were sexually abused within the past year and those who have never been sexually abused.

Effect sizes may significantly differ across original studies, so heterogeneity was statistically tested using the Q statistic. A significant Q indicates that effect sizes vary from study to study due to sampling error and other sources of variability (e.g., differences in study characteristics). In addition, we computed the I2 statistic that quantifies the percentage of total variation across the studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error [28]. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% are generally considered low, moderate, and high, respectively [29]. When heterogeneity is identified, its sources should be explored; however, the small sample sizes did not allow us to perform subgroup analyses. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using a fixed-effect model to assess the stability of the results. We removed individual studies one at a time and recalculated a weighted mean OR to examine if any one study overtly influenced the pooled effect size. We examined the possibility of publication bias, using Egger’s test and Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test. It is important to note that the heterogeneity statistics (Q, I2) and the results of the publication bias tests should be interpreted with caution because of low statistical power attributable to a small number of studies included in the meta-analysis. All analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 2 [30].

Results

Unprotected Sexual Intercourse

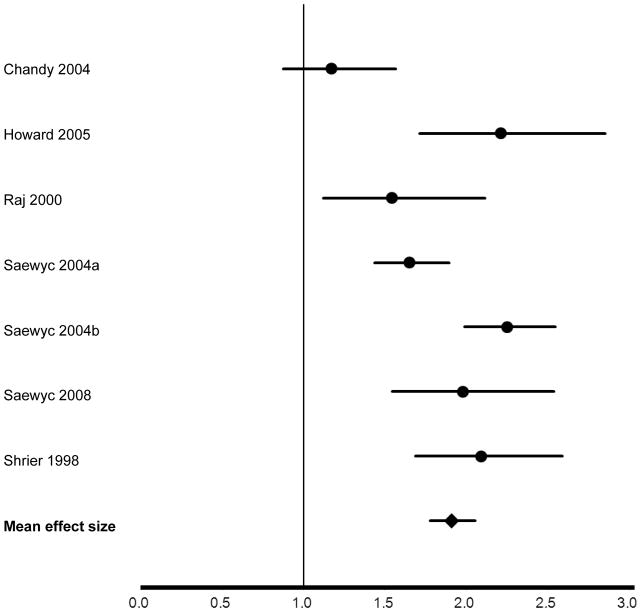

Individual effect sizes (ORs) for unprotected sexual intercourse ranged from 1.17 to 2.25. All but one primary study [22] showed significant associations between sexual abuse history and unprotected sexual intercourse. The overall weighted effect size estimate was 1.91 (Table 2). The Q statistic was 25.7 (p < 0.001), indicating that the strength of the association differed across the different studies. The I2 value of 76.6 also indicated a high level of heterogeneity in effects across studies. The weighted mean OR and individual ORs along with their 95% CI are shown as a forest plot in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Weighted Mean Effect Sizes (OR) for Risky Sexual Behaviors

| n | k | OR | 95% CI | Q | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unprotected intercourse | 40,237 | 7 | 1.91 | 1.78, 2.05 | 25.7*** | 76.6% |

| Multiple sexual partners | 36,683 | 6 | 2.91 | 2.68, 3.17 | 30.4*** | 83.6% |

| Pregnancy involvement | 35,750 | 8 | 4.81 | 4.39, 5.28 | 17.3* | 59.6% |

Note. n = number of subjects; k = number of effect sizes; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Forest plot comparing the rates of unprotected sexual intercourse between sexually abused boys and non-abused boys: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (Saewyc 2004a = 1992 data; Saewyc 2004b = 1998 data)

Sensitivity analysis showed no single study was substantially influential: the mean OR ranged from 1.75 (95% CI = 1.61, 1.92) to 2.01 (95% CI = 1.85, 2.19). No publication bias was found by Egger’s test (p = 0.369) or Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test (p = 0.368).

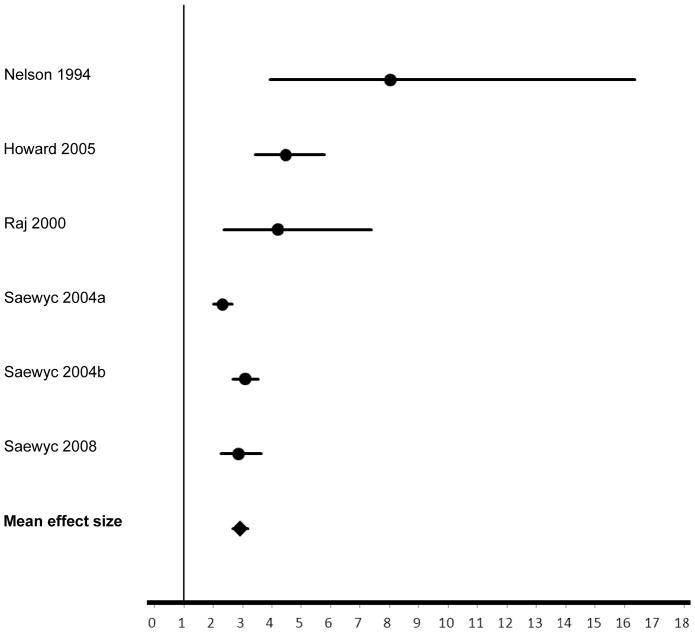

Multiple Sexual Partners

The overall mean OR for the association between sexual abuse and having multiple sexual partners was 2.91 (Table 2). The significant Q statistic (p < 0.001) suggests that there was systematic difference in the ORs across studies. A high level of inconsistency was indicated by the I2 value of 83.6, meaning that over 80% of the total variation among effect sizes is caused by sources other than sampling error. In this analysis, three studies [19, 23, 25] used having three or more lifetime sexual partners as an outcome. One study [4] had two independent effect sizes for the relationship between sexual abuse and having two or more sexual partners in the past year whereas another used having two or more sexual partners in the past 3 months [26]. We thus re-calculated the weighted OR for the former three studies, with the OR of 3.30 (95% CI = 2.67, 4.08) and I2 of 75.1. The results are presented as a forest plot in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing the rates of multiple sexual partners between sexually abused boys and non-abused boys: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (Saewyc 2004a = 1992 data; Saewyc 2004b = 1998 data)

The removal of any individual studies did not lead to significant changes in the mean OR. The recomputed ORs ranged from 2.78 (95% CI = 2.54, 3.03) to 3.33 (95% CI = 2.99, 3.70). No indication of publication bias was observed (Egger’s test, p = 0.107; Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test, p = 0.188).

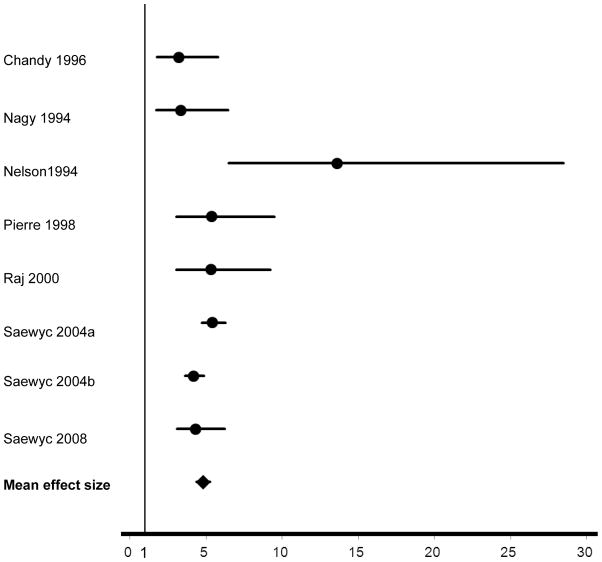

Pregnancy Involvement

On average, sexually abuse boys were nearly five times more likely than non-abused boys to report causing a pregnancy (Table 2). The Q statistic was significant (p = 0.015); the I2 statistic indicated a moderate level of heterogeneity (I2 = 59.6). ORs and respective 95% CI are graphically summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing the rates of pregnancy involvement between sexually abused boys and non-abused boys: Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (Saewyc 2004a = 1992 data; Saewyc 2004b = 1998 data)

The highest OR of 13.6 was reported by Nelson and colleagues [23], who defined sexual abuse as that which occurred within the past year. However, the removal of this study did not significantly change the overall OR (4.73, 95%CI = 4.31, 5.19); neither did the removal of any other studies. No indication of publication bias was observed (Egger’s test, p = 0.893; Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test, p = 0.711).

Discussion

Our results indicated that adolescent boys with a history of sexual abuse were more likely than non-abused boys to have engaged in unprotected sexual intercourse, to have had multiple sexual partners, and to have caused a pregnancy. The strengths of the relationship of sexual abuse with risky sexual behaviors ranged from modest to large. As with Arriola and colleagues’ study [10], unprotected intercourse had the smallest effect sizes. It appears that the associations of sexual abuse are stronger for rarer outcomes such as teen pregnancy. Regardless of the presence or absence of abuse experiences, unprotected intercourse may be relatively prevalent. The mean OR for adolescent pregnancy among women in Noll et al.’s meta-analysis [11] was 2.2 (95% CI = 1.94, 2.51). This effect size appears to be much smaller than that found in our study of young men (OR = 4.8), although results from the separate meta-analyses may not be directly comparable.

The potentially stronger effect of sexual abuse among boys may relate to cultural norms of masculinity and social stigma attached to same-gender sexual activity, which may lead to greater shame. The majority of perpetrators are men [12]; thus, males abused by another man experience conflicts about their masculinities and sexual orientation [4, 31]. Traditional gender stereotypes have associated victimization with femininity [32]. In a heterosexist society where same-gender sexual activity is unacceptable, even involuntary same-gender sexual experiences stigmatize adolescent males, regardless of their sexual orientation. Fears of being seen as feminine and/or gay are among common reasons for a delay in or lack of disclosure among male victims [31, 32]. In addition, sexually abused males are more likely than abused females not to disclose or to delay reporting the incident(s) [33]. Those males who do not disclose their abuse experience are not likely to receive social or professional support, perhaps having more profound influences on neurobiological, cognitive, and emotional development, and subsequent sexual practices.

As Goffman asserted [34], male victims may manage to cope with stigma attached to sexual abuse and same-sexual activity. They may control information to ‘pass as a normal’ [34]. Avoidance of disclosure is one of such strategies. Others include engaging in sexual behavior with females or fathering a child to camouflage their same-gender sexual experience [4, 35]. Substance abuse is another way of coping with stigma, which can lead to risky sexual behaviors [35]. Maladaptive management of stigma may increase the likelihood of risky sexual practices among sexually abused males.

Positive associations (i.e., OR > 1) do not mean that all abused adolescents engage in risky sexual behavior. Rather, sexual abuse experiences during childhood or adolescence may increase vulnerability to negative outcomes [13]. Some factors may reduce vulnerability and enhance resilience among sexual abuse victims. For example, social isolation and poor interpersonal relationships may contribute to risk involvement, but the presence of supportive family members, or caring peers or adults outside the family for those who have experienced incest may help abused teens or adults to learn positive coping strategies [4]. Such support could prevent them from developing psychological problems or engaging in risky sexual practices. Emotional and practical social support may be an important unmeasured moderator in the link between sexual abuse and risky behavior.

The present meta-analysis has some limitations. First, the small number of effect sizes included in the analyses prevented us from subgroup analyses when we found heterogeneity. Second, we analyzed school-based studies; thus, our results may not be generalizable to other adolescent populations, such as homeless and street-involved youth. Third, we cannot identify a causal relationship between or temporal order of sexual abuse and risky sexual practices. For example, there is a possibility that adolescent boys with pregnancy involvement may be vulnerable to sexual abuse. However, given that adolescent fathers are generally in their late teens and onset of sexual abuse often occurs in late childhood or early adolescence [12, 36], we may be able to infer that the abuse is more likely occurring before pregnancy involvement, rather than teen fathers are at higher risk for sexual abuse. Last, a limitation of this meta-analysis and original studies is that sexual abuse was measured as a dichotomous variable. The effects of sexual abuse may differ according to the type of abuse behavior, the age of onset, the frequency of abuse, the number of perpetrators, and the presence or absence of threats or force, as one study showed that those with a history of penetrative abuse were more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors than non-penetrative sexual abuse victims or those with no abuse history [37].

We need more studies on the effects of child and adolescent sexual abuse among males. For both males and females, sexual abuse experiences appear to influence their health and health practices; however, the strength of the association may differ for each gender. Future research also should focus more on sexual minority boys, who are at greater risk for both sexual victimization [38] and risky sexual practices [39], as well as on heterosexual adult men, because sexual abuse is not an issue only for sexual minority people. Furthermore, given the different cultural norms surrounding sexuality and sexual behavior for women and men, the mechanisms underlying these effects and interventions needed to reduce these effects may also be different.

Many interventions and educational programs have been developed and implemented for sexual health promotion and risk reduction. Most common educational approaches are designed to increase knowledge and skills, and promote changes in attitudes. The results of this meta-analysis suggest that sexual abuse prevention initiatives may be another effective strategy for reducing risky sexual practices, as proposed previously [4]. Implications for clinical practice include the need to screen for sexual abuse histories among both males and females, and to provide health education and support for sexually abused individuals who may be vulnerable to risky sexual behavior [15, 24, 40]. It is equally important to raise awareness about sexual abuse among males, to reduce the stigma associated with abuse experiences, and to increase access to access to gender-sensitive, supportive health care for survivors.

Implications and Contribution.

Sexual abuse puts young men at greater risk for unprotected intercourse, multiple partners, and pregnancy involvement. Our findings highlight the importance of including boys in sexual abuse prevention initiatives, raising awareness about the needs of male survivors, and screening all people, regardless of gender, for a history of sexual abuse.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by the Stigma and Resilience Among Vulnerable Youth Consortium, which is funded by the grant #HOA 80059 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Saewyc, PI).

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts

All authors do not have any interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research.

References

- 1.Oddone Paolucci E, Genuis ML, Violato C. A Meta-analysis of the Published Research on the Effects of Child Sexual Abuse. J Psychol. 2001;135:17–36. doi: 10.1080/00223980109603677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stoltenborgh M, van IJzendoorn MH, Euser EM, et al. A Global Perspective on Child Sexual Abuse: Meta-analysis of Prevalence Around the World. Child Maltreat. 2011;16:79–101. doi: 10.1177/1077559511403920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Bellis MD. Developmental Traumatology: The Psychobiological Development of Maltreated Children and Its Implications for Research, Treatment, and Policy. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:539–564. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saewyc EM, Magee LL, Pettingell SE. Teenage Pregnancy and Associated Risk Behaviors Among Sexually Abused Adolescents. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:98–105. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.98.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kendall-Tackett K. The Health Effects of Childhood Abuse: Four Pathways by Which Abuse Can Influence Health. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26:715–729. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson HW, Widom CS. An Examination of Risky Sexual Behavior and HIV in Victims of Child Abuse and Neglect: a 30-year Follow-up. Health Psychol. 2008;27:149–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith DW, Davis JL, Fricker-Elhai A. How Does Trauma Beget Trauma? Cognitions About Risk in Women With Abuse Histories Child Maltreat. 2004;9:292–303. doi: 10.1177/1077559504266524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briere JN, Elliott DM. Immediate and Long-term Impacts of Child Sexual Abuse. Future Child. 1994;4:54–69. doi: 10.2307/1602523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen AC, Thompson EA, Morrison-Beedy D. Multi-system Influences on Adolescent Risky Sexual Behavior. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33:512–527. doi: 10.1002/nur.20409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arriola KRJ, Louden T, Doldren MA, et al. A Meta-analysis of the Relationship of Child Sexual Abuse to HIV Risk Behavior Among Women. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:725–746. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noll JG, Shenk CE, Putnam KT. Childhood Sexual Abuse and Adolescent Pregnancy: a Meta-analytic Update. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:366–378. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmes WC, Slap GB. Sexual Abuse of Boys: Definition, Prevalence, Correlates, Sequelae, and Management. JAMA. 1998;280:1855–1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Purcell DW, Malow RM, Dolezal C, et al. Sexual Abuse of Boys: Short- and Long-term Associations and Implications for HIV Prevention. In: Koenig LJ, Doll LS, O’Leary A, et al., editors. From Child Sexual Abuse to Adult Sexual Risk: Trauma, Revictimization, and Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. pp. 93–114. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peter T. Exploring taboos: Comparing Male- and Female-perpetrated Child Sexual Abuse. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24:1111–1128. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shrier LA, Pierce JD, Emans SJ, et al. Gender Differences in Risk Behaviors Associated with Forced or Pressured Sex. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:57–63. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagy S, Adcock AG, Nagy MC. A Comparison of Risky Health Behaviors of Sexually Active, Sexually Abused, and Abstaining Adolescents. Pediatrics. 1994;93:570–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez JT, Lodico M, DiClemente RJ. The Effects of Child Abuse and Race on Risk-taking in Male Adolescents. J Natl Med Assoc. 1993;85:593–597. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lodico MA, DiClemente RJ. The Association Between Childhood Sexual Abuse and Prevalence of HIV-related Risk Behaviors. Clin Pediatr. 1994;33:498–502. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saewyc EM, Taylor D, Homma Y, et al. Trends in Sexual Health and Risk Behaviours Among Adolescent Students in British Columbia. Can J Hum Sex. 2008;17:1–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devries KM, Free CJ, Morison L, et al. Factors Associated with the Sexual Behavior of Canadian Aboriginal Young People and Their Implications for Health Promotion. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:855–862. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.132597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devries KM, Free CJ, Morison L, et al. Factors Associated with Pregnancy and STI Among Aboriginal Students in British Columbia. Can J Public Health. 2009;100:226–230. doi: 10.1007/BF03405546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandy JM, Blum RW, Resnick MD. Sexually Abused Male Adolescents: How Vulnerable Are They? J Child Sex Abuse. 1997;6:1–16. doi: 10.1300/J070v06n02_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson DE, Higginson GK, Grant-Worley JA. Using the Youth Risk Behavior Survey to Estimate Prevalence of Sexual Abuse Among Oregon High School Students. J Sch Health. 1994;64:413–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb03264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pierre N, Shrier LA, Emans SJ, et al. Adolescent Males Involved in Pregnancy: Associations of Forced Sexual Contact and Risk Behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 1998;23:364–369. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(98)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raj A, Silverman JG, Amaro H. The Relationship Between Sexual Abuse and Sexual Risk Among High School Students: Findings from the 1997 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:125–134. doi: 10.1023/A:1009526422148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Howard DE, Wang MQ. Psychosocial Correlates of U.S. Adolescents Who Report a History of Forced Sexual Intercourse. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. A Basic Introduction to Fixed-effect and Random-effects Models for Meta-analysis. Res Syn Meth. 2010;1:97–111. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying Heterogeneity in a Meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, et al. Comprehensive Meta-analysis, version 2. Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alaggia R. Disclosing the Trauma of Child Sexual Abuse: A Gender Analysis. J Loss Trauma. 2005;10:453–470. doi: 10.1080/15325020500193895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorsoli L, Kia-Keating M, Grossman FK. ‘I keep that hush-hush’: Male Survivors of Sexual Abuse and the Challenges of Disclosure. J Couns Psychol. 2008;55:333–345. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.3.333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hebert M, Tourigny M, Cyr M, et al. Prevalence of Childhood Sexual Abuse and Timing of Disclosure in a Representative Sample of Adults from Quebec. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:631–636. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goffman E. Management of spoiled identity. In: Rubington E, Weinberg MS, editors. Deviance: The Interactionist Perspective. Text and Readings in the Sociology of Deviance. New York, NY: The MacMillan Company; pp. 344–348. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saewyc EM, Poon CS, Homma Y, et al. Stigma Management? The Links Between Enacted Stigma and Teen Pregnancy Trends Among Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Students in British Columbia. Can J Hum Sex. 2008;17:123–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, et al. The Victimization of Children and Youth: A Comprehensive, National Survey. Child Maltreat. 2005;10:5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA, et al. Characteristics of Sexual Abuse in Childhood and Adolescence Influence Sexual Risk Behavior in Adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:637–645. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9109-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. A Meta-analysis of Disparities in Childhood Sexual Abuse, Parental Physical Abuse, and Peer Victimization Among Sexual Minority and Sexual Nonminority Individuals. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1481–1494. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blake SM, Ledsky R, Lehman T, et al. Preventing Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Adolescents: the Benefits of Gay-sensitive HIV Instruction in Schools. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:940–946. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.6.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiIorio C, Hartwell T, Hansen N. Childhood Sexual Abuse and Risk Behaviors Among Men at High Risk for HIV Infection. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:214–219. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]