Abstract

Contrary to popular belief, policies on drug use are not always based on scientific evidence or composed in a rational manner. Rather, decisions concerning drug policies reflect the negotiation of actors’ ambitions, values, and facts as they organize in different ways around the perceived problems associated with illicit drug use. Drug policy is thus best represented as a complex adaptive system (CAS) that is dynamic, self-organizing, and coevolving. In this analysis, we use a CAS framework to examine how harm reduction emerged around heroin trafficking and use in Tanzania over the past thirty years (1985-present). This account is an organizational ethnography based on of the observant participation of the authors as actors within this system. We review the dynamic history and self-organizing nature of harm reduction, noting how interactions among system actors and components have coevolved with patterns of heroin us, policing, and treatment activities over time. Using a CAS framework, we describe harm reduction as a complex process where ambitions, values, facts, and technologies interact in the Tanzanian socio-political environment. We review the dynamic history and self-organizing nature of heroin policies, noting how the interactions within and between competing prohibitionist and harm reduction policies have changed with patterns of heroin use, policing, and treatment activities over time. Actors learn from their experiences to organize with other actors, align their values and facts, and implement new policies. Using a CAS approach provides researchers and policy actors a better understanding of patterns and intricacies in drug policy. This knowledge of how the system works can help improve the policy process through adaptive action to introduce new actors, different ideas, and avenues for communication into the system.

Keywords: policy analysis, complex adaptive systems, heroin, harm reduction, prohibition, Tanzania

Introduction

(Inter)national and local policies concerning the transportation, sale, and consumption of illicit drugs encompass a wide range of perspectives along a continuum from broad legalization to stringent prohibition. Many of us citizens assume these and other policies are composed and implemented in a rational, purposeful manner by a select group of government officials after careful consideration of all the available facts. This rational/technical model is the basis for the “evidence-based” turn in drug policy where some actors attempt to eliminate local values and political motives from the decision-making process, believing that sufficient knowledge of social problems, backed by sound research, will produce effective policies with predictable outcomes. Yet even in instances where scientific research informs decisions, local values and politics continue to define what constitutes proper “evidence” and how it should be applied, or ignored, in policy (Lancaster 2014; Monaghan, 2011). Policy – encompassing both formulation and implementation – remains an unpredictable enterprise. The increasing democratization of policy engenders greater uncertainty, with more actors bringing their varied values, goals, and evidence to the process. How can we researchers and stakeholders better understand the complex environment in which policy occurs? How can we apply such knowledge to reduce uncertainty and improve the policy process? What is needed is an approach that accounts for the broad range of policy actors, structures, ideas, and technologies as they interact over time to enact policy within a continuously changing socio-political context.

There are a variety of theories and models researchers can use to analyze policy related to drug use (see Ritter & Bammer, 2010). Models such as the advocacy coalition framework (Sabatier, 1988) and multiple streams theory (Kingdon, 2011) provide specific guidelines for analyzing policies according to certain basic assumptions about socio-political structures and processes. These guidelines are useful when the research question focuses on a particular practice or segment of policy, but the precision of such models does not permit a more expansive examination of policies when the structures and actions are not as clearly defined. Instead of specific models or theories, what is required in such situations is a more generalized theoretical analysis using what Ostrom (2011) describes as a higher-order framework.

Frameworks identify the elements and general relationships among these elements that one needs to consider for institutional analysis and they organize diagnostic and prescriptive inquiry. They provide a general set of variables that can be used to analyze all types of institutional arrangements. Frameworks provide a metatheoretical language that can be used to compare theories. They attempt to identify the universal elements that any theory relevant to the same kind of phenomena needs to include. (p. 8)

One such framework uses concepts of complexity theory to depict policy as a complex adaptive system (CAS) comprised of many actors who organize around a particular social problem, bringing diverse ambitions, values, and facts to deliberate the issue and enact their decisions in a continuously changing social environment (Boulton, 2010; Klijn, 2008; Mitchell, 2009; Morçöl, 2012). Applying a CAS framework to policy does not necessarily supplant other models of policy – many of these models incorporate aspects of complexity theory – but instead contributes to our understanding as researchers and citizens by expanding the concepts and tools to include a broader range of components and their interactions in our analyses and subsequent actions.

In this study we examine harm reduction in Tanzania as a complex adaptive system, noting the interactions among different actors with competing perspectives on how to address the supply, demand, and use of heroin, and how these interactions produce new structures, institutions, and decisions over time. The Tanzanian situation serves as an interesting case study for several reasons. First, it is one of the few countries in sub-Saharan Africa to implement harm reduction. Since 2007, government agencies and non-government organizations (NGO) in Tanzania have carried out a variety of strategies to reduce the incidence of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other blood-borne infections among people who inject drugs, including targeted outreach, HIV counseling and testing, medically-assisted therapy, and needle and syringe programs (Ratliff, et al., 2013). Second, because heroin entered the Tanzanian drug market relatively recently (in the 1980s), local policies do not reflect a lengthy and contentious history where the emphasis was on morality and criminality. This is in contrast to Western countries, where a century of strict prohibition has only recently given way to decriminalization, legalization, and harm reduction approaches. Finally, as the authors of this study, our understanding of harm reduction as a CAS in Tanzania is based primarily on our perspectives as actors within this policy system where we have observed the emergence of harm reduction from the beginning, and we continue to work within and monitor the system as it unfolds.

As actors within the system, we have two distinct but overlapping objectives for applying a CAS perspective: 1) as an analytic framework to understand and represent current heroin policies Tanzania as a complex, emergent system, and 2) as a guide for taking adaptive action to foster policy within a dysfunctional system (Eoyang & Holladay, 2013; Mitleton-Kelly, 2003). After a brief review of complexity theory and the dynamic equilibrium model used in our analysis, we tell the story of harm reduction as it emerged in Tanzania over the past thirty years, describing the interactions of actors, institutions, and technologies in deliberating and implementing policy. We illustrate how this story represents a complex adaptive system, where actors are continually organizing system components to produce new policies. We conclude this paper by showing how stakeholders can use adaptive action to reduce the uncertainty of complexity, creating conditions where people can effectively work together to improve the socio-political legitimacy and sustainability of their policy decisions.

Integrating complexity in policy analysis: the dynamic equilibrium model

To better understand and facilitate these policy processes, it is important to define the relevant properties and capacities of complex adaptive systems we use in our analysis. There are several distinct theories and applications of complexity across the natural and social sciences (Mitleton-Kelly, 2003), but in the policy and public administration literature three characteristics of complexity stand out: non-linear dynamics, self-organization, and coevolution (Butler & Allen, 2008; Klijn, 2008; Morçöl, 2012; Teisman, van Burren, & Gerrits, 2009). Non-linear dynamics refers to the multifaceted, co-constitutive relationships between a large number of individual components – actors, materials, institutions, values, facts, places – as parts of the system, where changes in the properties and interactions of components and the system over time are difficult to predict. Prediction is difficult because such changes are emergent (Sawyer, 2005), as interactions among individual actors and other components can create or transform high-order structures, and these structures, in turn, change the properties of, and interactions between, the constituent components. Such interactions generate feedback loops that amplify what is happening in the system (positive or reinforcing feedback), or counteract changes to the system (negative or balancing feedback). Another aspect of non-linearity is that small changes among a few components can lead to extensive transformations across the entire system, or across multiple systems; policy actions do not produce proportional outcomes. The system is thus more than the sum of its components, and is not reducible to simple models or generalizable laws.

These dynamics prompt the self-organization of the system in question. Systems emerge as distinct entities through their internal, non-linear dynamics, and tend to resist influence from outside the system as they generate their own structures, properties, and behaviors. From a policy-making perspective, self-organization generates order (or equilibrium) so actors can reach some semblance of consensus and make decisions about social problems. A crucial dimension of self-organization concerns boundary judgments, where actors define the system according to their perceptions and ambitions. These boundaries are porous in that they allow for interactions between systems; boundaries are also fluid as they expand and contract to include or exclude components in the process of self-organizing. Perhaps the most fundamental example of a boundary judgement is in defining what the problem is. Studies of drug policy show how decision makers have created boundaries around certain drugs according to their perceived effects and harms rather than strong scientific evidence (Fraser & Moore, 2011; Monaghan, 2011). In turn, policy responses reinforce boundaries by defining people who use drugs and limiting the scope of interventions according to those constructs.

As researchers, we must recognize that we too create boundaries as part of our analytic endeavors (Morçöl, 2012): an earlier draft of this article defined the boundary for this study to encompass illicit drug policy for Tanzania in its entirety, including both prohibitionist and harm reduction perspectives. However, after receiving comments from reviewers, we decided that we could offer a clearer example of a CAS if we defined the system boundaries to focus on harm reduction as a distinct system within a larger drug policy environment. In this article, we use a fluid definition of “system” to represent how actors and components overlap and reconfigure in complex ways.

Systems and their components do not self-organize in isolation, but rather coevolve in interaction with other systems; coevolution also occurs between components within a system. Coevolution is especially pertinent when it comes to local implementation of national policies, where actors from different systems must work with each other in order to realize different ambitions (e.g., securing support at the local level, achieving results at the national level; Klijn, 2008). Learning is an important dimension of coevolution as actors select courses of action and make decisions from a range of possibilities based on their previous experiences and their interactions with other components and systems. Each decision creates an “historical object” that actors remember in their future interactions (Mitleton-Kelly, 2003). Actors then observe the effects of their decisions, adjusting future interactions as they develop a better understanding of the dynamics within and between systems. This leads to continuous evaluation and reconfiguration of the system as actors respond to unexpected events and adapt to emergent structures.

To analyze the historical emergence of harm reduction in Tanzania as a complex adaptive system and provide guidance for interacting within that system, we used the dynamic equilibrium model (Van Buuren & Gerrits, 2008). This model depicts policy decisions as temporary states of stability where actors, processes, and other components of the system are aligned in equilibrium. This equilibrium persists until some other event destabilizes the system, and then a new round of decision-making occurs. In policy rounds (Teisman, 2000), deliberative events and decisions proceed in a sequential manner as the system incorporates new actors with competing intentions who organize their activities in response to each other as well as to previous events and decisions.

Actors often self-organize and coevolve within policy system(s) because they recognize they must coordinate their activities with each other to reach a decision that requires consensus in a democratic context. To achieve this, actors need to reconcile conflicts between personal decision models that are composed of ambitions, values, and facts. First, ambitions reflect the actor's interests or goals in the policy process. Second, values refer to the perceptions and preconceived notions the actors bring to the process. Finally, facts are the forms of knowledge actors use to support their ambitions and values. Policy interactions thus entail the negotiation of competing ambitions, composing the appropriate frames to accommodate divergent values, and producing facts to support these emergent ambitions and frames. The system achieves equilibrium when actors align their ambitions, values, and facts to reach a decision.

Coevolution occurs through the mutual interactions of actors both within and beyond their specific policy system, where they learn about the various systems’ components, structures, and dynamics, and negotiate compromises to align values and ambitions (Butler & Allen, 2008). The continuity between rounds is important because these systems generate their own histories of values and events that, in turn, actors adopt and apply to future interactions and decision-making (Morçöl, 2012). Another round begins when new actors introduce their competing ambitions, values, and facts to produce different policy decisions; within such a system, existing policies are thus reaffirmed when actors are excluded or convinced to accept established ambitions, values, and facts.

Methodology

This analysis is based on our experiences as actors moving within and across multiple systems as we have enacted harm reduction in Tanzania over the past fifteen years. As actors, we are composing this ethnography to reflexively recount “how things work” from our positions within the processes of organizing Tanzanian drug policy (Watson, 2011). Our ethnography is not based on a formal research project, but rather reflects our observant participation within this dynamic, emergent, and coevolving system over time. This approach is best described as an organizational ethnography, where our tacit understanding of structures and processes stems from our long-term immersion as “members” of that organization, or, in this case, a system that encompassed several interdependent organizations. One advantage of this ethnographic approach is that it provides the flexibility to use different methods and capture a variety of voices across the system(s) as interactions unfold (Moeran, 2009). This ethnography is part of the harm reduction system: an exercise in emergent learning and documentation that will assist in future self-organization and coevolution through adaptive action.

As the authors of this ethnography, we have been involved in harm reduction from initial rapid assessments of injecting drug use (JM) in the late 1990s through comprehensive studies of injecting practices a few years later (JM, SM), funded by the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). All of us have also assisted in the implementation of harm reduction programs since 2008, designing and evaluating programs and procedures, directing and conducting intervention activities, and sharing our experiences and observations at conferences and meetings with a wide variety of stakeholders. In writing this account, we have employed conventional qualitative methods, including semi-structured interviews (SM) and informal conversations with people who use drugs (all authors), conversations with various stakeholders such as local residents and leaders (all authors), observations of local and international policy meetings (PK, SM, FM, JM), and content analysis of news articles and policy documents (SM, JM, ER). The following account and analysis reflects our understanding as actors within this system, learning about the many different intersecting components and how they transform the system, using this knowledge to create new structures, and helping shape socio-political interactions through self-organization with other actors and components.

Harm Reduction in Tanzania: A Story of Self-Organization and Coevolution

In this section, we describe the actors, events, and other system components (e.g., perceptions, substances) that have fueled the emergence and transformation of harm reduction policy in Tanzania over the past thirty years. Following the dynamic equilibrium model, we use policy rounds to delineate specific time periods when particular policy activities prevail. In our analysis, each round represents a temporary state of equilibrium where actors’ values, ambitions, and facts converged in a decision to change the existing system(s): the acceptance of heroin in East African drug markets, the passage of local legislation to prohibit drug trafficking and use, the initiation of research to introduce new facts, the implementation of harm reduction, and the negotiation of new drug laws. As the system reacts to these new policies and practices, it becomes destabilized and self-organizes through the negotiation of convergent and divergent forces. Across these rounds, we chart the entry of new actors and components, the promotion of different values, facts, and ambitions, the creation of institutions and structures, and the adoption of technologies and terminologies. We selected the temporal boundaries of each round based on what we consider to be pivotal periods in the self-organization and coevolution of harm reduction in Tanzania; other observers and participants might establish different boundaries in telling the story according to their experiences.

Round 1 (ca. 1985-1994): Accepting heroin in East Africa

The story of harm reduction in Tanzania begins with the introduction and acceptance of heroin into the local drug market (Figure 1). Alcohol, cannabis, and khat have extensive histories of production and consumption in the region (Carrier & Klantschnig, 2012), but, until recently, there was not a local market for other intoxicating substances. In the 1980s, international smugglers began using Tanzania as a transshipment point for heroin between Asia and Europe (McCurdy & Maruyama, 2013), creating a local market for consumption of the drug as well. With the acceptance of heroin in East Africa – a policy decision enacted through the alignment of local consumers, distributors, and corrupt leaders – the global system of production and trafficking began to coevolve with the local system(s) of substance use to create greater demand for heroin, generating positive feedback (supply-and-demand) and increasing the flow of drugs into the region.

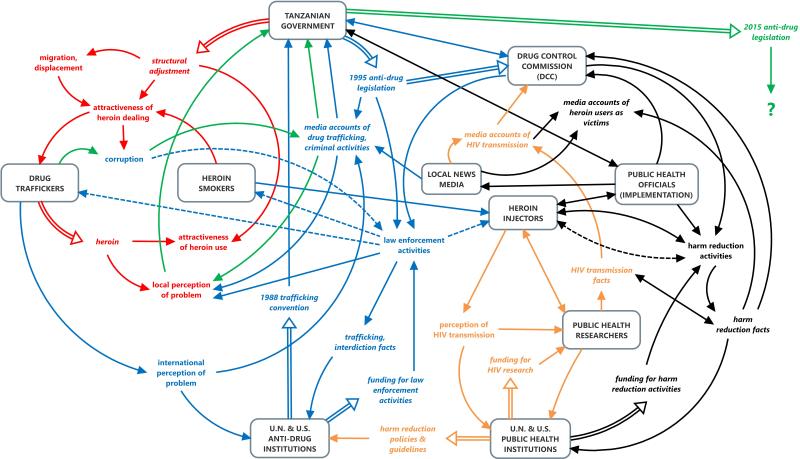

Figure 1. Harm reduction in Tanzania as a complex adaptive system.

Diagram shows interactions between main actors (in boxes) with other components of the complex system. Interactions include reinforcing (positive; solid line) or balancing (negative; dashed line). “Hollow” lines indicate major policy or funding decisions. Components include perceptions and activities, as well as those “tangible” written elements such as facts, policies, and media accounts (italicized). Policy rounds are presented as colors: Round 1 (ca. 1985-1994) in red; Round 2 (1995-2003) in blue; Round 3 (2003-2007) in orange; Round 4 (2007-2012) in black; Round 5 (2012-present) in green.

This emerging heroin market in East Africa also coevolved with other socio-economic systems in a variety of ways and across different levels of society. Beckerleg (1995) describes how the introduction of heroin coincided with a rapidly expanding tourist industry on the Kenyan coast. As tourism displaced the fishing industry, migrants from the interior moved to the coast to buy land and establish businesses; this, in turn, prompted local youth to pursue economic opportunities and consumer desires that included dealing and consuming heroin. McCurdy (2014) describes a similar process in Tanzania, where the transition to an open market economy in the mid-1980s disrupted social structures and government programs. Young people left the support of family and community, traveling great distances to new places to participate in this global economy. With little experience, limited skills, and lacking social capital, many failed in to find suitable vocations through which they could compete in the modern world. This socio-economic transformation occurred at the same time AIDS was taking a heavy toll, further disrupting the social fabric and exacerbating experiences of disaffection in a rapidly changing society. It is within these environmental conditions that local youth self-organized around heroin, incorporating it into their social lives in different ways: to participate in the underground economy; to express modern identities and group solidarities; to medicate the structural violence of modernity and suffering of loss and exclusion.

During Round 1, harm reduction was not a consideration because international observers and local political leaders did not identify heroin as a serious problem in Tanzania. The entry of heroin reconfigured existing social, political, and economic systems as residents and officials coevolved with this novel disruptive technology. The establishment of a local market for heroin represents a form of equilibrium, in part, because interactions reflected the alignment of values and ambitions toward accepting heroin as a means of participating in the modern economy and lifestyles. Yet this market equilibrium also reflects the lack of alignment in opposition to heroin, as many actors were unaware of these structural transformations or uncertain about how to interact with this new component.

Round 2 (1995-2003): Establishing prohibitionist policy

While the heroin market emerged in Tanzania with little opposition, the historical construction of heroin as a serious problem at the international level set the stage for changes in Tanzanian drug policy (Carstairs, 2005). Actors at the international level were designing new strategies to align the ambitions, values, and facts of all member nations around the control of narcotic supply and demand. In the 1980s, the United Nations and the United States government began linking drug trafficking to international criminal syndicates, highlighting the pervasiveness and severity of the global trafficking system:

During 1988, the gravity of the situation, which preoccupies the highest levels of governments, has led to strong counter-attacks mounted at the community, national, regional and multilateral levels. Heavy emphasis is being placed on identifying and bringing to justice not only the master-minds of the criminal syndicates, but whole networks involved in the illicit production, manufacture and distribution (International Narcotics Control Board, 1988: 3).

For the U.S. and U.N., there was already a high degree of alignment because they had been collaborating on anti-drug policy for decades (Carstairs, 2005). Both actors shared the same ambition of eliminating drug use, and the same values that drugs are always harmful and associated with criminality. Moreover, they collaborated to produce facts to reflect those ambitions and values: reporting the amount of drugs seized and number of arrests support the notion that there is a problem, and that increased law enforcement is the appropriate policy response. Efforts to highlight the global links between drugs and crime culminated in the 1988 Convention against the Illicit Trafficking in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. The U.S. and U.N. then applied diplomatic pressure to Tanzania and other African nations to ratify and enforce international conventions on narcotics and other drugs.

In 1995 the Tanzanian legislature passed the “Drugs and Prevention of Illicit Traffic in Drug Act” to prohibit and penalize drug production, trafficking, and abuse. The Tanzanian government ratified the U.N.'s 1988 trafficking convention in 1996, and in 1997 established the Drug Control Commission (DCC) to develop national policies and implement international conventions on drug control in Tanzania. Since enacting these policies, the Tanzanian government has received substantial training and financial support from the U.N. Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the U.S. government for its efforts in supply and demand reduction. From a systems perspective, Tanzania became part of the global prohibitionist system, promoting boundary judgements that identified heroin as a problem in Tanzania because those associated with the drug – traffickers, dealers, consumers – are criminals. This produces a simple positive feedback loop characteristic of a technical/rational model of policymaking: defining the problem (boundary judgement), implementing the appropriate policy response (self-organization), and generating support through the interaction with other social and government institutions and the production of facts (coevolution), including those facts demonstrating the efficacy of the policy.

For the first eight years within the Tanzanian drug policy environment, harm reduction remained dormant because prohibitionist values and ambitions dominated global and local discussions. The DCC produced reports for U.N. and U.S. anti-drug agencies on its interdiction and policing activities, and local media played its role in reporting government numbers on seizures and arrests. However, in spite of law enforcement successes, many Tanzanians viewed the heroin problem as intractable: supply-and-demand feedback ensured traffickers would continue to import heroin, while the corruption of local officials involved in trafficking balanced the efforts of those working to eliminate the market. These market countermeasures created a negative feedback structure that has prolonged the public's focus on the criminal dimensions of international trafficking, local distribution, and consumption of heroin, validating and sustaining the prohibitionist policy approach.

Since legislation and other systems interactions focused on criminalization and prohibitionist policy responses, there was little mention of the association between intravenous drug use and HIV in Tanzania. As recently as 2001, the National Policy on HIV/AIDS did not acknowledge injecting drug use as a potential source of HIV transmission (United Republic of Tanzania, Prime Minister's Office, 2001), and in 2003 the first National Strategic Framework on HIV/AIDS said “transmission routes like intravenous drug use... are rare” (Tanzania Commission for AIDS, 2002: 5). This omission in documents and policies is understandable because intravenous drug use was rare until the early 2000s. Tourists and traffickers first introduced a “brown” form of heroin that most people smoked; it was only in the late 1990s, when a purer form of “white” heroin appeared in East Africa, that locals began injecting the drug (Beckerleg, 1995). This reconfiguration of drug markets toward injecting coevolved with the biological systems of HIV and other blood-borne infections to produce a very effective means of transmission. So while local decision makers rejected harm reduction during Round 2, the public discussion of local heroin use created an environment where people could talk about different aspects of drug use. This prompted other actors with public health values and harm reduction ambitions to add their voices to the system. What harm reduction proponents needed were appropriate facts to frame the problem of heroin in a way that expanded the system's boundaries beyond its narrow focus on criminality.

Round 3 (2003-2007): Producing knowledge of harms

In light of increasing reports of injecting drug use in Tanzania, researchers and health officials from local and foreign institutions began self-organizing toward the provision of harm reduction to prevent further spread of HIV. To garner support from Tanzanian politicians in a prohibitionist policy environment, the proponents of harm reduction realized they would need to generate and disseminate facts to highlight the local public health implications of heroin use. With financial support from the U.S. National Institutes Drug Abuse, researchers conducted numerous studies of drug use practices in Dar es Salaam and on the island of Zanzibar between 2003 and 2007 to demonstrate the links between heroin injection and HIV transmission (Dahoma, et al., 2006; McCurdy, et al., 2005; 2006; Timpson, et al., 2006; Williams, et al., 2007). Results from these surveys indicated that the prevalence of HIV infection among those who injected heroin was between 26% and 42% in Dar es Salaam, compared to an overall national prevalence of 9% (Williams, et al., 2009).

Publishing results in academic journals is usually not enough to sway public opinions or influence government officials, so researchers were determined to disseminate the facts to a broad range of stakeholders. On World AIDS Day in December 2006, the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) and the University of Texas School of Public Health (UT) conducted a workshop in Dar es Salaam to report the peer-reviewed results of their epidemiologic research and to highlight the issue of injecting drug use and HIV. Members of the Tanzanian parliament, NGOs, donor agencies, and the news media attended the workshop. This dissemination of facts provided the impetus for the state and donor agencies to respond to the HIV epidemic among people who inject drugs in Tanzania.

Preventing HIV transmission was not the only ambition of actors who spoke out about heroin use and its harms. During this round, a young member of the Tanzanian parliament, Amina Chifupa, began a public campaign against drug traffickers, highlighting the socio-economic effects of drug use on local youth (McCurdy, et al. 2007). Her descriptions of disaffection gave greater meaning to emerging heroin use within local discourses surrounding the exclusionary economic policies of structural adjustment. She also illuminated the role of corruption, calling on the officials to expose “drug barons” and their government protectors in an effort to halt trafficking. Other actors offered their perspectives of drug use beyond the boundaries of criminality and law enforcement. Young men we interviewed noted that the lack of education and job opportunities left them feeling bored, hopeless, and pursuing heroin as a pastime (McCurdy, 2013). The DCC also supported the alignment of values and ambitions by highlighting deficiencies in drug treatment and prevention policies.

These efforts to develop harm reduction at the national level coevolved with international efforts toward alignment and equilibrium. Public health institutions such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) were crucial actors who highlighted the need to address HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. Their persistence in the dissemination of facts and distribution of funds to harm reduction helped transform the ambitions and values of the UNODC and the U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy so they could integrate harm reduction into their institutional language and guidelines for HIV prevention. Harm reduction thus emerged as a viable policy system to challenge the primacy of a prohibitionist system that had heretofore focused solely on reducing the supply of, and demand for, heroin through law enforcement activities.

Round 3 was a crucial time in which harm reduction became a possible policy solution in Tanzania. Proponents reconfigured the boundaries of the system by successfully re-presenting people who consume heroin as “vulnerable citizens” who deserve treatment instead of imprisonment. Harm reduction did not supplant existing anti-drug policies, but offered a complementary system that could support prohibitionist concerns, insofar as treatment and prevention efforts would facilitate demand reduction. This alignment of ambitions, values, and facts across a variety of actors at different institutional levels generated the equilibrium needed to implement harm reduction in Tanzania.

Round 4 (2007-2011): Implementing harm reduction

Building upon the equilibrium from Round 3, harm reduction implementation proceeded quickly. In 2007, the Tanzanian government requested funding from the CDC to implement HIV prevention programs for people who inject drugs, and the DCC also integrated treatment and prevention into national drug control policies. Tanzania's second National Strategic Framework on HIV/AIDS called for interventions to prevent the transmission of HIV through injecting drug use (Tanzania Commission for AIDS, 2007). Later that year, the Tanzanian government received funding from the U.S. President's Emergency Funds for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) for Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences to initiate HIV intervention projects for people who inject heroin in Dar es Salaam under the umbrella of the Tanzania AIDS Prevention Program (TAPP). These activities include targeted outreach to disseminate information and cleaning kits, coordination of support groups and psychosocial services through partner NGOs, and HIV testing and counselling. Other internationally-funded programs conduct similar harm reduction activities in Dar es Salaam and on the island of Zanzibar (see Ratliff, et al., 2013). The supportive response from stakeholders, including people who use heroin, created the positive feedback to drive these changes forward.

To build and maintain public support for harm reduction policies, TAPP has conducted workshops for physicians, media personnel, and law enforcement officials to educate those communities on program activities and issues pertaining to people who use heroin. NGOs working with people who inject drugs also coordinate activities with police to reduce harassment of program clients, and to divert people who use heroin from arrest and incarceration into treatment and other intervention programs. Officials in law enforcement have responded by implementing a strategy of community policing, where police work with neighborhood residents to address emergent problems, self-organizing according to the specific socio-political context (Butler & Allen, 2008; Lehmann, 2012). Groups advocating and implementing harm reduction prevention policies – including clients of intervention programs – have also participated in World AIDS Day, International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, and other public events to demonstrate their support for, and participation in, current harm reduction and prohibitionist policies.

Actors at the international level have also changed their positions. Some observers note that the INCB ignored WHO recommendations on health issues in the past, avoiding the language of harm reduction because it did not fit the model of criminalization and control (Carstairs, 2005; Room, 2005). However, as the AIDS pandemic progressed and NGOs voiced their concerns at annual meetings of the U.N.'s Commission on Narcotic Drugs, there has been a softening of the drug control rhetoric when it comes to harm reduction activities (Babor, et al., 2010; Room & Reuter, 2012). UNODC has joined WHO and UNAIDS to produce comprehensive guidelines for the prevention of HIV transmission through injecting drug use (World Health Organization, 2009). Since 2008, PEPFAR has focused its HIV prevention efforts toward “key populations” such as people who inject drugs (Needle, et al., 2012).

From the perspective of public discourse, it appears as though the alignment of ambitions, values, and facts toward harm reduction has progressed without incident. Boundaries have expanded to include people who inject drugs as a vulnerable population, and institutional actors, such as physicians and social workers, have organized networks to help affected persons access social services. However, the equilibrium of policy and funding decisions at the (inter)national level rarely holds when it comes to implementation at the local level.

In 2011, TAPP expanded its activities to include medically-assisted therapy (MAT) for clients. Because of its novelty in the African setting and its established efficacy as an “evidence-based intervention,” MAT has become the centerpiece of TAPP activities. Since it is one of many components of this complex, non-linear system, dispensing methadone produces a variety of consequences beyond its intended pharmacological outcomes on individual clients. As Rhodes and colleagues note (2015), methadone is “made” into multiple substances through implementation; using CAS language and concepts, methadone coevolves and is transformed through its interactions with other components and systems. For example, international agencies have created boundaries to limit interactions with methadone by focusing solely on its use in HIV prevention. In Tanzania, methadone is a substance designated only to reduce HIV transmission: it is one component of this harm reduction strategy along with comprehensive health services, individual and family counseling, and occupational training. It is not intended to treat addiction and foster recovery as in other settings or systems. Yet treatment and recovery is still a “side-effect” of methadone use, and this is what is most visible to the community as MAT clients return home from the clinic day after day. Methadone thus becomes a medicine to cure addiction in the eyes of all who use heroin. But it is available only to those who inject heroin; those who smoke the drug in combination with tobacco or cannabis are denied access. The reasoning behind these exclusionary boundaries for harm reduction are difficult for many who use heroin to understand, and this creates animosity between those who inject and smoke heroin. In frustration, those denied access try to subvert harm reduction activities by spreading negative rumors, refusing to participate in other harm reduction programs, or chasing outreach workers from their gathering places. Such instability and reorganization within the drug market requires similar reorganization in harm reduction as these systems coevolve and continue to reinforce and challenge these and other boundary judgements.

In this harm reduction system, methadone is also a narcotic. Because it was created to address all aspects of narcotics control, the DCC assumed a leading role in the procurement of methadone. The DCC's role concerning methadone was also problematic because it was not coordinating its activities with the Tanzanian Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW). Since national drug policies were initially based on prohibitionist international treaties, the government maintains strict regulations on methadone and other therapeutic narcotics out of concern they could be diverted toward illegal consumption. MAT clients must travel to the clinic every day so the pharmacist can watch them consume their dose. This time-consuming procedure is a reason why some cannot sustain participation in the program as it limits their ability to seek work in another city or devote sufficient time to domestic and family responsibilities.

While there have been great strides in advancing harm reduction in Tanzania, policy dynamics in Round 4 underscore continuing disagreements. Where policy decisions are characterized by uncertainty, there is a greater emphasis on values (Mitchell 2009), so the framing of messages becomes more salient. Dispensing methadone is an acceptable harm reduction activity because it also corresponds to the values of prohibitionists in reducing the demand for heroin. This is the reason for using terms such as “medically-assisted therapy” rather than “oral-substitution therapy”: the implication that one is simply “substituting” one opiate for another goes against established prohibitionist values of eliminating drug use through interdiction or treatment activities. The contested meaning of methadone reflects the persistence of competing ambitions, where the DCC wanted to maintain control over an illegal substance while the MoHSW sought greater availability for treatment of heroin dependence and other medical applications. Finally, needle and syringe programs have been more difficult to implement in this system because, while they reduce the risk of transmitting blood-borne infections, they do not reduce the number of people who inject. There also remains the perception that in offering needles and/or syringes the government would be condoning, or even encouraging, illicit drug injection.

Round 5 (2012-present): Negotiating new laws

While the media has produced mostly sympathetic portrayals about people who use drugs (“People using drugs deserve support”, 2013), stories about those who import drugs into Tanzania have been critical (Austin 2014). This is due, in part, to the perception that corrupt government officials are responsible for drug trafficking in the country and that the current laws are too lenient (“How do we fare in the drug fight?”, 2012). For example, current anti-drug legislation allows judges to impose a fine and/or a prison sentence on persons convicted of dealing or using drugs. In practice, judges have been more likely to fine drug traffickers and dealers who then resumed their distribution of heroin after paying the fine. The appearance of leniency in such cases has led to calls for tougher sanctions against drug traffickers and dealers.

As democratic institutions continue to evolve and assert their power in Tanzanian politics, government corruption remains a priority. This is especially true in recent years as the government has undertaken a constitutional review (beginning in 2011), with an eye toward expanding human rights and limiting the powers of elected officials. The media and presumed public outcry has spurred Tanzanian lawmakers into revising the 1995 anti-drug law. In a preliminary draft of “The Drug Control and Enforcement Act, 2014” (United Republic of Tanzania, 2014), there were references to rehabilitation and reintegration of drug “users,” but most of the language emphasized criminality and punishment. For example, the definition of “illicit traffic” includes the “use or consumption” of narcotics. Also, a person found in possession of small amounts of drugs or paraphernalia “commits an offence, and upon conviction shall be liable to a fine of not less than one million shillings [about US$550] or to imprisonment for a term of three years or to both” (Part III, sec. 19). This “re-entry” of prohibitionist values and ambitions in the new legislation reflects the strength of historic and fundamental system boundaries (Pel, 2009), and highlights the need for continuous learning and self-organization through system(s) interactions.

As part of the legislative process, the government requested public commentary on a draft of the bill (“Air views on drugs: govt”, 2014). There was also a stakeholders meeting in January 2015 to deliberate the new bill. At that meeting, TAPP, other concerned NGOs, and members of civil society offered suggestions to minimize the negative effects on HIV prevention programs. A large number of people who use(d) heroin also voiced their concerns at the meeting: of the 50 people in attendance, about half had personal experience with heroin use. The ministers of parliament and other government officials (about a dozen in attendance) were receptive to their presence and listened intently to their concerns. This indicated yet another shift in boundaries for Tanzanians who use heroin: through their participation in harm reduction and anti-drug activities, they have emerged as stakeholders who contribute to policy discourse. Suggestions included redefining the terminology of addiction and treatment, eliminating many of the punitive measures targeting those who only consume drugs, and specifying the role of the MoHSW in matters of public health on drug issues. Participants also expressed concern about the bill's criminalization of people found in the company of someone who possessed drugs. Parliamentary debates on the bill in March 2015 were heated, with some lawmakers calling for the execution of convicted drugs dealers (Masato, 2015). To further complicate the current process of drug control legislation in Tanzania, the INCB has recently called on the Tanzanian government to ease restrictions on therapeutic narcotics such as morphine (Lugongo & Buguzi, 2015). Observers believe parliament will approve the bill sometime before the general election of president, members of parliament, and local officials scheduled in October 2015.

Policy changes proposed in Round 5 reflect the continuous entry of new actors and ideas in a dynamic, coevolving political environment. In the minds of the public, media, and many legislators, the existing law had to be revised because it did not provide sufficient penalties for drug traffickers and those who control the heroin market in Tanzania. The local media played an influential role in setting the agenda around criminalization of drug traffickers, but it also framed the issue to divert blame from those who use heroin (Lancaster, et al., 2011). But these discussions are about more issues than is evident in the news media. Since Tanzanian families started discussing what to do about heroin use thirty years ago, a broad spectrum of actors and stakeholders have also interjected their ambitions, values, and facts into these deliberations. So while the current round of national policy making emerged to create legislation that increases the penalties for the production, trafficking, and use of illegal drugs, actors in public health and affected communities have mobilized a coordinated response to mitigate the effects of any new laws on harm reduction. Having coevolved and learned about the socio-political complexity of policy, many of the actors have “softened” some of their positions in an effort to harmonize perspectives and to gain greater political legitimacy for their decisions. Yet there is still a concern that while the new anti-drug legislation might not specifically criminalize activities associated with heroin treatment and HIV prevention, the overall effect of the law might nonetheless constrain harm reduction activities as they are implemented in community settings. It remains to be seen how actors will organize in this and in subsequent rounds as heroin use and the attendant policy debates in Tanzania continue to coevolve.

Adaptive Action: Applying What We Have Learned

This explanation of harm reduction in Tanzania as a complex adaptive system offers a more comprehensive portrayal of policy processes than do the typical models of implementation that focus a select number of variables. Using the dynamic equilibrium model, we outline the emergence of harm reduction across different policy rounds covering the past thirty years (see Figure 1). We describe the self-organizing interactions among actors and components in each round, noting how actors responded to emergent transformations in the policy environment, creating new structures and relationships. Some of the new structures involved boundary judgements, especially pertaining to how others would perceive people who use heroin: as “criminals” in Round 2, as “vulnerable citizens” in Rounds 3 and 4, and as “stakeholders” in Round 5. In turn, these boundaries influenced subsequent interactions. Many of these interactions reflect non-linear dynamics where changes in one component created a cascade of events that reconfigured one or more systems. For example, many in harm reduction think of methadone in a universally positive light, but its introduction as part of the Tanzanian harm reduction effort in Round 4 also produced some negative effects: excluding heroin smokers from a form of addiction treatment, transforming the way people who smoke and inject heroin organize, generating mistrust of outreach workers, and creating friction between government entities. As we actors have learned more about these changes and their underlying mechanisms, we have coevolved with other policies and socio-political systems, and adjusted our values and ambitions to improve our interactions within this contentious policy environment.

In keeping with the CAS perspective, this remains a dynamic account so our story and diagram are likely to change in the future – even in reference to past events. For example, we have identified Round 5 of the policy process beginning in 2012 as the government initiated the revision of the anti-drug laws. We included this boundary judgement because we anticipate a change in legislation will have an effect on local heroin policies. However, the laws have not been enacted as of the writing of this manuscript, so we have no way of knowing what their impact will be. At some point in the future, we will revisit this account and perhaps modify the boundary or eliminate that round altogether. This is the essence of complex adaptive systems: we actors are always learning and coevolving together around dynamic processes, creating new ways to organize other actors and components over time as the system reconfigures itself.

We consider harm reduction in Tanzania to be a functional complex adaptive system because it furnishes an enabling environment for the entry of new actors, ideas, and components. Even though changes do not always proceed in the direction or as rapidly as some might prefer, actors are still willing to listen to each other and learn about our different ambitions, values, and facts. However, some systems are more dysfunctional when it comes to promoting change because they are characterized by inertia, where actors or components are excluded from participation, new ideas such as harm reduction are discouraged, and avenues for communication are blocked. This is the often case for nations and governments where centralized, hierarchical power structures exclude other stakeholders from participating in policy discussions. Inertia in a policy system invariably produces uncertainty, for while the decision making processes might not change the contexts of implementation are continually evolving. The U.S. “war on drugs” is an example of such a policy failure: the criminalization and militarization to reduce supply and demand over decades did little to reduce demand other than creating an immense carceral system because anti-drug policy failed to coevolve with other systems. In these cases, actors who want to create a more adaptive system can observe how the system “works,” uncover those complex and dynamic mechanisms that stifle change, and offer solutions to improve system performance in terms of producing durable and effective policies.

Eoyang and Holladay (2013) introduce adaptive action as a means of fostering such change to counter inertia. To improve the capacity for adaptation within a system, they focus on three dimensions that account for patterns of change: container, difference, and exchange. Container refers to the boundaries and properties of the system, and to improve adaptive capacity actors could expand or contract the system by removing some components or altering the policy environment (e.g., working with international entities to help influence national policies). Difference refers to variation within the system, which is crucial for resolving tension, stimulating change, and steering actors away from group-think. Exchange is another term for the interactions within a system. Because these dimensions are interdependent, a change to one is likely to alter the others. There is no specific strategy to change the system in this way, but often requires trial and error based on what is already known about the system's properties and processes, and what actors learn through repeated adaptive actions.

There are many points where actors engaged in adaptive action to create change in the Tanzanian harm reduction system. Round 3 was a particularly crucial period when HIV and public health actors entered the drug policy arena and expanded the scope of the problem (container), highlighting the harms of injecting heroin (difference), and disseminating these facts through workshops, peer-reviewed publications, and direct discussions (exchange). Government officials could have ignored these actions as they have done in many other settings throughout the history of drug policy, but they allowed new actors, ideas, and interactions into the system. This process of reconfiguring the system to avoid inertia and promote change is continuous. As we authors/actors coevolve within the drug policy system, and with other socio-political systems, we are able to expand our activities as we learn how everything “works” in concert.

As an organizational ethnography, this first-hand account of a complex adaptive system does not describe every influential component or interaction within and beyond the system. As actors positioned within the system, we do not fully understand all of its machinations; one can never completely understand a large system such as the one we have described here because no one can see everything that is happening. Yet this is more of an epistemological shortcoming than a practical concern. We wrote about this complexity framework not to answer some specific research question or provide strategies for to address problems, but rather to offer a perspective of how one might approach challenges related to the functioning of socio-political systems in which they interact with others. We chose broad boundaries of time and space to demonstrate how far a drug policy system could extend – and this is in a setting with a relatively brief history of heroin use. As actors within this self-organizing system in Tanzania, we are still trying to make sense of other actors, events, and components in interaction. As we apply a solution to address one problem, it invariably creates new challenges. But in adopting a CAS perspective to our policy interactions we can learn how to work with other system actors and components to produce more effective and durable policies over time.

Acknowledgements

We thank our fellow actors in drug policy in Tanzania for their dedicated work. We would also like to acknowledge the Tanzania AIDS Prevention Project (TAPP) and its partner NGOs (Blue Cross Society of Tanzania, Kimara Peer Educators, Youth against Vulnerable and Risky Behaviors, Centre for Human Rights Promotion) for their continuing efforts in harm reduction. SM received partial support for research presented herein from NIDA grants R21 DA025478 and R21 DA019394. The four anonymous reviews for this manuscript also provided suggestions that improved our story.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Air views on drugs: govt. [5 April 2015];The Citizen (Tanzania) 2014 Sep 13; from http://www.thecitizen.co.tz/News/national/Air-views-on-drugs--govt/-/1840392/1992044/-/9eicvwz/-/index.html.

- Austin S. Unlawful drug barons silences authorities, however, controversial. [15 April 2015];Business Times (Tanzania) 2014 Dec 12; from http://www.businesstimes.co.tz/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4343:unlawful-drug-barons-silences-authorities-however-controversial&catid=1:latest-news&Itemid=57.

- Babor T, Caulkins J, Edwards G, Fischer B, Foxcroft D, Humphreys K, et al. Drug policy and the public good. Oxford University Press; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Beckerleg S. ‘Brown sugar’ or Friday prayers: Youth choices and community building in coastal Kenya. African Affairs. 1995;94:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Boulton J. Complexity theory and implications for policy development. Emergence: Complexity & Organization. 2010;12:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Butler MJR, Allen PM. Understanding policy implementation processes as self-organizing systems. Public Management Review. 2008;10:421–440. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier N, Klantschnig G. Africa and the war on drugs. Zed Books; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carstairs C. The stages of the international drug control system. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2005;24:57–65. doi: 10.1080/09595230500125179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahoma MJU, Salim AA, Abdool R, Othman AA, Makame H, Ali AS, et al. HIV and substance abuse: The dual epidemics challenging Zanzibar. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies. 2006;5:129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Eoyang GH, Holladay RJ. Adaptive action: Leveraging uncertainty in your organization. Stanford Business Books; Stanford: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser S, Moore D. Governing through problems: The formulation of policy on amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) in Australia. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2011;22:498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How do we fare in the drug fight? [April 5 2015];The Guardian (Tanzania) 2012 Jun 26; from http://www.ippmedia.com/frontend/functions/print_article.php?l=43018.

- International Narcotics Control Board . Report of the International Narcotics Control Board 1988. Vienna: 1988. [7 April 2015]. from http://www.incb.org/documents/Publications/AnnualReports/AR1988/AR_1988_English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd ed. Longman; Boston: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn EH. Complexity theory and public administration: What's new? Public Management Review. 2008;10:299–317. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster K. Social construction and the evidence-based drug policy endeavor. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2014;25:948–951. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster K, Hughes CE, Spicer B, Matthew-Simmons F, Dilon P. Illicit drugs and the media: Models of media effects for use in drug policy research. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2011;30:397–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann K. Dealing with violence, drug trafficking and lawless spaces: Lessons from the policy approach in Rio de Janeiro. Emergence: Complexity & Organization. 2012;14:51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lugongo B, Buguzi S. Legalize some narcotics, govt urged. [26 March 2015];The Citizen (Tanzania) 2015 Mar 5; from http://www.thecitizen.co.tz/News/national/-/1840392/2643138/-/l5ab8rz/-/index.html.

- McCurdy S. Tanzanian heroin users and the realities of addiction. In: Klantsching G, Carrier N, Ambler C, editors. Drug in Africa: Histories and ethnographies of use, trade, and control. Palgrave; New York: 2014. pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy S, Kilonzo G, Williams M, Kaaya S. Harm reduction in Tanzania: An urgent need for multisectoral intervention. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2007;18:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy S, Maruyama H. Heroin use, trafficking, and intervention approaches in local and global contexts. In: Webb J, Giles-Vernick T, editors. Global health in Africa: Historical perspectives on disease control. Ohio University Press; Athens: 2013. pp. 211–234. [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy S, Ross M, Kilonzo GP, Leshabari MT, Williams M. HIV/AIDS and injection drug use in the neighborhoods of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82:S23–S27. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(06)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy S, Williams ML, Kilonzo GP, Ross MW, Leshabari MT. Heroin and HIV risk in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Youth hangouts, mageto and injecting practices. AIDS Care. 2005;17:S65–S76. doi: 10.1080/09540120500120930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masato M. MPs demand life jail for drug barons. [26 March 2015];Daily News (Tanzania) 2015 Mar 25; from http://www.dailynews.co.tz/index.php/local-news/42968-mps-demand-life-jail-for-drug-barons.

- Mitchell SD. Unsimple truths: Science, complexity, and policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mitleton-Kelly E. Ten principles of complexity and enabling infrastructures. In: Mitleton-Kelly E, editor. Complex systems and evolutionary perspectives on organisations: The application of complexity theory to organisations. Pergamon; New York: 2003. pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Moeran B. From participant observation to observant participation. In: Ybema S, Yanow D, Wels H, Kamsteeg F, editors. Organizational ethnography: Studying the complexities of everyday life. Sage; Los Angeles: 2009. pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan M. Evidence versus politics: Exploiting research in UK drug policy making? Policy Press; Bristol: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Morçöl G. A complexity theory for public policy. Routledge; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, Fu J, Beyrer C, Loo V, Abdul-Quader AS, et al. PEPFAR's evolving HIV prevention approaches for key populations – people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and sex workers: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;60:S145–S151. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825f315e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. Background on the Institutional Analysis and Development framework. Policy Studies Journal. 2011;39:7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pel B. The complexity of self-organization: Boundary judgments in traffic management. In: Teisman G, van Buuren A, Gerrits L, editors. Managing complex governance systems: Dynamics, self-organization and coevolution in public investments. Routledge; New York: 2009. pp. 116–133. [Google Scholar]

- People using drugs deserve support. [27 June 2013];The Guardian (Tanzania) 2013 Jun 27; from http://www.ippmedia.com/frontend/index.php?l=56424.

- Ratliff EA, McCurdy SA, Mbwambo JKK, et al. An overview of HIV prevention interventions for people who inject drugs in Tanzania. Advances in Internal Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/183187. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/183187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rhodes T, Closson R, Guise A, Paparini S, Strathdee S. Towards “evidence-aking intervention approaches in the social science of implementation science: The making of methadone in East Africa. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.01.002. [this issue] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter A, Bammer G. Models of policy-making and their relevance for drug research. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2010;29:352–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R. Trends and issues in the international drug control system – Vienna 2003. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37:373–383. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10399810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Reuter P. How well do international drug conventions protect public health? Lancet. 2012;379:84–91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier PA. An advocacy coalition framework of policy change and the role of policy-oriented learning therein. Policy Science. 1988;21:129–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer RK. Social emergence: Societies as complex systems. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tanzania Commission for AIDS [2 May 2013];National Multi-Sectorial Strategic Framework on HIV/AIDS, 2003-2007. 2002 from http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01390/WEB/IMAGES/TANZANIA.PDF.

- Tanzania Commission for AIDS [2 May 2013];The Second National Multi-Sectorial Strategic Framework on HIV and AIDS (2008-2012) 2007 from http://www.tacaids.go.tz/documents/NMSF%20%202008%20-2012.pdf.

- Teisman GR. Models for research into decision-making processes: On phases, streams and decision-making rounds. Public Administration. 2000;78:937–956. [Google Scholar]

- Teisman G, van Buuren A, Gerritts L, editors. Managing complex governance systems: Dynamics, self-organization, and coevolution in public investments. Routledge; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Timpson S, McCurdy S, Leshabari M, Asami A, Kilonzo GP, Williams M. Substance abuse and HIV risk in Tanzania. African Journal of Drug and Alcohol Studies. 2006;5:158–169. [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania The Drug Control and Enforcement Act, 2014. Bill Supplement. Gazette of the United Republic of Tanzania. 2014 Oct 31;44 [Google Scholar]

- United Republic of Tanzania, Prime Minister's Office [15 April 2015];National Policy on HIV/AIDS. 2001 from http://www.policyproject.com/pubs/other/Tanzania_National_Policy_on_HIV-AIDS.pdf.

- Van Buuren MW, Gerrits L. Decisions as dynamic equilibriums in erratic policy processes: Positive and negative feedback as drivers of non-linear policy dynamics. Public Management Review. 2008;10:381–399. [Google Scholar]

- Watson TJ. Ethnography, reality, and truth: The vital need for studies of ‘how things work’ in organizations and management. Journal of Management Studies. 2011;48:202–217. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, McCurdy S, Atkinson J, Kilonzo GP, Leshabari MT, Ross M. Differences in HIV risk behaviors by gender in a sample of Tanzanian injection drug users. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:137–44. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams ML, McCurdy SA, Bowen AM, Kilonzo GP, Atkinson JS, Ross MW, Leshabari MT. HIV seroprevalence in a sample of Tanzanian intravenous drug users. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21:474–483. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization [20 April 2015];WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS technical guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users. 2009 from http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/idu/idu_target_setting_guide.pdf.