Abstract

PEG-based hydrogels have become widely used as drug delivery and tissue scaffolding materials. Common among PEG hydrogel-forming polymers are photopolymerizable acrylates such as polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA). Microfluidics and microfabrication technologies have recently enabled the miniaturization of PEGDA structures, thus enabling many possible applications for nano- and micro- structured hydrogels. The presence of oxygen, however, dramatically inhibits the photopolymerization of PEGDA, which in turn frustrates hydrogel formation in environments of persistently high oxygen concentration. Using PEGDA that has been emulsified in fluorocarbon oil via microfluidic flow focusing within polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) devices, we show that polymerization is completely inhibited below critical droplet diameters. By developing an integrated model incorporating reaction kinetics and oxygen diffusion, we demonstrate that the critical droplet diameter is largely determined by the oxygen transport rate, which is dictated by the oxygen saturation concentration of the continuous oil phase. To overcome this fundamental limitation, we present a nitrogen micro-jacketed microfluidic device to reduce oxygen within the droplet, enabling the continuous on-chip photopolymerization of microscale PEGDA particles.

Introduction

Acrylate-based polymers are regarded for their transparency, color variation, robust mechanical properties, and elasticity1. Acrylates can be readily photopolymerized on industrial scales and are widely used in industrial chemical processes as adhesives, sealant composites, and protective coatings1,2. Relative to other synthetic monomers, acrylates are often preferred due to their biocompatibility and chemical versatility, allowing modification with a range of monofunctional or multifunctional moieties3,4. Oligomeric acrylates can controllably produce highly crosslinked networks via photopolymerization5. Exploiting these characteristics, a class of photopolymerizable polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based hydrogels has been based upon acrylate polymerization chemistries6-8.

Photopolymerization is a convenient and cytocompatible alternative to solvent-based or thermal curing, and can be carried out both in-vitro and in-vivo9. The photoinitiated free radical polymerization of acrylates is typically performed in the presence of a photoactive initiator that generates free radicals upon exposure to ultraviolet light. It is quite well known, however, that acrylate free radical polymerization is strongly inhibited by the scavenging of radicals by oxygen10-12. Dissolved oxygen is typically present throughout bulk PEGDA solutions, but is quickly consumed, allowing polymerization to proceed. Prolonged oxygen inhibition can occur if the solution is in contact with an oxygen source, such as an air interface or a surface with a sufficiently high oxygen solubility and permeation rate. On the microscale, the inhibition of photopolymerization reactions is exacerbated by increased surface-to-volume ratios.

The attraction for using PEGDA as a cell encapsulant and tissue scaffold arises from the combination of its tissue-like physical properties, which can be tailored to closely mimic extracellular matrices, cytocompatibility and synthetic versatility. Over a certain polymer composition range, highly water-swollen PEGDA hydrogel networks have been proven to be cytocompatible encapsulants for many cell types including fibroblasts13, chondrocytes14, vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs)15, endothelial cells (ECs)16, osteoblasts17, neural cells18, and stem cells19. Synthetic customization of PEGDA macromolecular architecture and chemistry provides a broad diversity of properties, making it an attractive alternative to natural hydrogels. For example, PEGDA hydrogel networks can be readily decorated with cell-adhesive peptide groups that allow the formation of bioactive hydrogels that promote cell adhesion, spreading and tissue elaboration20. Modifications to the PEG crosslinker itself can impart the ability to spatially and temporally remodel the hydrogel by, for instance hydrolytic6, proteolytic7 or optical degradation21. Directed network remodeling has become widely adopted as a strategy for temporally regulating hydrogel properties.

Microscale PEGDA hydrogel particles, or “microgels” are of emerging importance to the sensing22, drug23 and tissue engineering24 communities due to intraparticle diffusion, facile antibody25 or oligonucleotide conjugation26, and potential for in vivo applications17,27,28. PEG microgels have been successfully fabricated via stop-flow lithography, a single-phase microfluidic step-wise photopolymerization technique. Stop-flow lithography in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic devices exploits the elastomer's high oxygen permeability and oxygen transport rates to maintain thin unpolymerized zones near channel surfaces due to the inhibition by oxygen24,29. These unpolymerized films prevent the adhesion of polymerized structures to channel surfaces, allowing them to be harvested as particles. Numerous variations have been based upon this principle, including the fabrication of complex shape microparticles24,30, cell encapsulation24, and complex particle bar-coding31,32. Stop-flow lithography has allowed particles to be produced with arbitrary and precise two-dimensional shapes defined by the photo-mask. Incomplete polymerization has been exploited to produce particles with lateral crosslinking density gradients that arise from oxygen diffusion across the particle edges33. Despite the broad versatility of this technique, the required presence of ambient oxygen constrains particle fabrication rates, and limits the ability to simultaneously dictate particle size and polymer composition24.

PEG microspheres may be fabricated at very high rates by emulsifying two-phase oil-water suspensions. Commonly, microparticles are prepared by bulk aqueous phase emulsification via sonication34, vortexing35, or homogenization36, or by microfluidic drop-wise emulsification37. Following emulsification, stabilized particles suspended within the immiscible oil are photopolymerized by irradiation38,39. Hydrogel particles made by either bulk or microfluidic emulsification have potential applications across a wide range of medical research applications including targeted drug-delivery40, cell encapsulation7, assembly of complex scaffold frameworks41, and biomaterial encapsulation42.

Bulk emulsification is typically performed with relatively large volumes of solution, and produces larger microparticles (>100μm) over a wide size distribution. The photopolymerization of bulk emulsions is similar to that of bulk homogeneous PEG macromer solutions, in which oxygen inhibition is quickly overcome as oxygen in the surrounding oil phase is rapidly depleted.

Microfluidic emulsification, on the other hand, is a precise and repeatable process that can produce uniform size particles with an exceptional control of their respective composition. To preserve size homogeneity, it is desirable to photopolymerize droplets upon the device immediately after they are formed. This is possible and has been demonstrated with large droplets43,44, or droplets of high PEG or initiator concentration45. Conversely, continuous photopolymerization has not been demonstrated in smaller droplets with lower, cytocompatible PEG-initiator compositions. In both of these cases, the oxygen inhibition of free radical polymerization, amplified by fluorocarbon oils and PDMS devices, prohibits photopolymerization. As a result, despite the tremendous potential suggested for the microfluidic fabrication of monodisperse, small (<40μm) cytocompatible PEG hydrogel microspheres, their continuous fabrication has not yet been reliably achieved.

In order to enable acrylate polymerization within microscale emulsion droplets, various techniques to eliminate oxygen during free radical polymerization have been proposed, such as vacuum-based degassing46, nitrogen purging47, PDMS diffusion barriers48, adding oxygen scavengers to the oil phase44, and photopolymerization under sealed, inert gas environments49. Most of these oxygen-shielding techniques are cumbersome or costly to implement. For instance, isolating entire microfluidic workstations, including pumps, syringes, tubing, devices and microscopes) from oxygen is impractical. And, for an oxygen-degassed PDMS device, the experimental run time is temporary limited to minutes before oxygen is replenished throughout the device. To address oxygen-inhibition during polymerization and enable stable, long-term microfluidic microparticle synthesis, we present a unique nitrogen micro-jacketed PDMS microfluidic device design (Figure 1A). Performance of the N2 micro-jacketed device is characterized experimentally and complemented with a coupled O2 reaction-diffusion finite element numerical model. This platform overcomes the limitations of previous droplet photopolymerization devices and provides the ability to independently specify polymerized particle size and composition, while making available a range of cytocompatible compositions that were previously inaccessible.

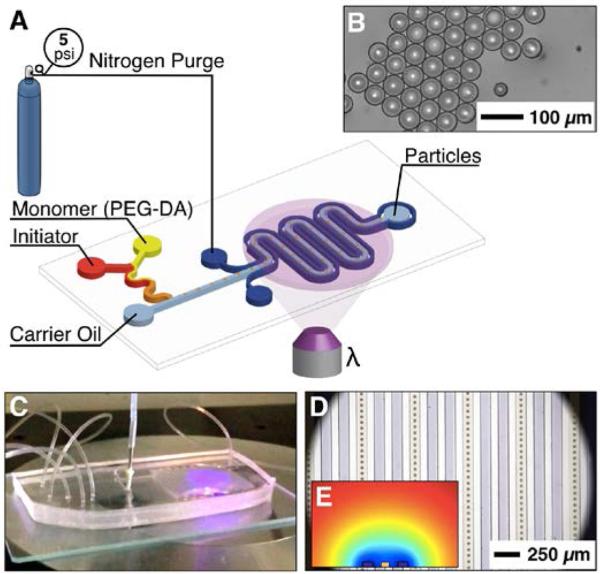

Figure 1.

A) Schematic of on-chip “one pot” hydrogel microparticle fabrication via microfluidic emulsification, nitrogen purging and photopolymerization. B) Fully polymerized hydrogel particles (r ~ 50 μm). C) A photograph of the integrated microfluidic device in operation. UV exposure of the droplet transfer serpentine belt can be observed on the right hand side of the device. D) Micrograph of mono-disperse particles flowing through a serpentine belt (ivory) surrounded by nitrogen micro-jacket (purple). E) COMSOL simulated cross-sectional concentration profile of nitrogen (blue) displacing air (red) in PDMS that was reached after ~10min.

Materials and Methods

PDMS microfluidic devices were fabricated from single layer photolithographically patterned masters using standard PDMS soft lithography techniques50,51, and bonded to 2″×3″ glass slides. To facilitate droplet formation and minimize aqueous phase wetting, microchannel surfaces were pre-treated with Aquapel (Pittsburgh Glass Works, LLC). The pre-treatment consisted of Aquapel injection followed by an oil flush to remove excess agent. Shown schematically and in optical micrograph images (Figure 1 B and C, respectively), PDMS devices consisted of a 100 μm thick droplet generation and transport channel sheathed by a 100 μm thick nitrogen jacketing channel. The PDMS wall thickness between parallel fluid and nitrogen channels was 100 μm, sufficient to hold the PDMS-glass bond intact under pressures up to 5 psi at the device inlet (pressures exceeding 10 psi required increasing the wall thickness between channels to 250 μm).

Figure 1A illustrates the microfluidic device design, which includes PDMS microchannels for fluid flow, flanked by channels to carry nitrogen. This configuration sufficiently elevated the local nitrogen concentration, depleted oxygen in the PMDS and prevented oxygen from diffusing through and interacting with fluids. We have exploited the gas permeability of PDMS to saturate the microchannel region with nitrogen (Figure 1D) during PEGDA microparticle polymerization.

Fluid Control

Fluidic inlet and outlet holes of the nitrogen-jacketed PDMS particle photopolymerization device were connected to fluid sources and collection reservoirs, respectively, via microbore Tygon® tubing (.01″ID × .03″OD, ND-100-80, United States Plastic Corp.). Nitrogen was introduced into the device through microbore Teflon tubing at a positive pressure of ~5 psig. The nitrogen gas flow was controlled with an electronic pressure regulator connected to LabVIEW National Instruments software that allowed the pressure to be adjusted and specified at the device inlet. An open gas outlet was not used, as it was found the N2 purging was more effective if the outlet remained closed and the channel pressurized (as seen in Figure 1D, gas channels are slightly inflated under nitrogen pressure). Operating fluids (oil and hydrogel-forming macromer solution) were loaded into disposable plastic syringes (1-10ml, Becton Dickinson) and the flow of each component independently controlled by syringe pump (Nemesys syringe pump, Cetoni, Germany).

Device Operation

A microfluidic T-junction50 channel configuration was used to emulsify the macromer solution into a fluorocarbon oil, Novec™ 7500, 3M (+2% wt. Krytox FSL 157 as a surfactant, DuPont). Fluorocarbon oils have a host of advantages over mineral oil for droplet production, including lower viscosity, greater specific gravity, and excellent cytocompatibility. Despite Novec's higher oxygen solubility that frustrates photopolymerization relative to mineral oil, the stated advantages result in droplet populations that can be more easily produced at small sizes and with tighter size distributions, as documented in Figure 3A. Ancillary advantages of Novec include facile particle phase extraction with minimal remaining oil residue, and high two-phase stability relative to other commonly used oils52,53.

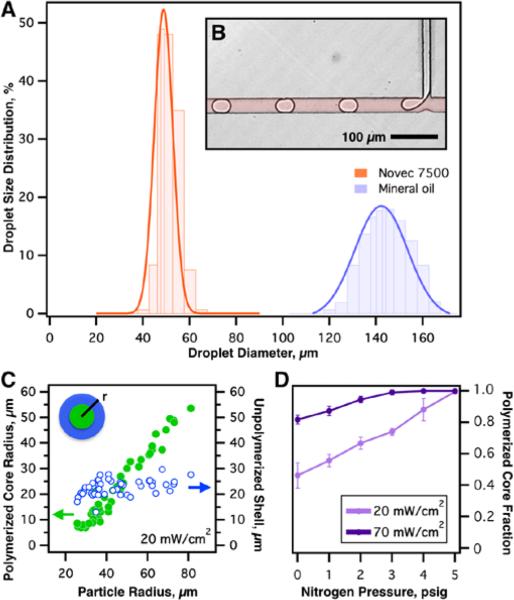

Figure 3.

Droplet size distribution using two different oils (Figure 3 A) in an identical microfluidic T-junction device (B) under identical flow conditions shows a reduction in size and improvement in monodispersity with fluorocarbon oil vs. mineral oil. Experimental results of polymerization behaviour within hydrogel particles of varying diameter are shown in (C). The unpolymerized shell surrounding the polymerized core is visually determined for a set of droplets approximately 20 μm, and is dictated by the oxygen concentration in the adjacent oil phase, and does not change with particle radius. The limits of polymerization are visualized in (D), which shows nitrogen jacket purge pressure and UV intensity effects on polymerization behaviour. Clearly, UV intensity can be used to tune the shell thickness, but complete polymerization is impossible without oxygen purging.

Produced droplets travelled downstream in a long serpentine channel with a total residence time ranging from 1-5 seconds. Droplets contained monomer solution at concentrations of 10-40% PEGDA-700 (v/v) (CAS Number 26570-48-9, Sigma Aldrich), 1-6% Irgacure 1173 initiator (v/v) (CAS Number 7473-98-5, Sigma Aldrich) in water. Droplet composition was varied to alter reaction kinetics and enable model validation. By varying continuous and dispersed fluid flow rates, the produced droplet size was controlled at the T-junction over a range of r = 20-80 μm. In the serpentine channel section, droplets were exposed to UV light (10-70 mW/cm2). Illumination was performed with a fluorescent illumination system (Prior Lumen-200), and an inverted microscope (IX71, Olympus) with a DAPI filter cube and 2-10X objectives. UV light intensity was measured with a handheld cure site radiometer (Power Puck II, Uvicure). Produced microparticles were collected in a microcentrifuge tube (Eppendorf) or directly upon a cover slip for imaging with bright field microscopy. Partially polymerized particle recovery from the oil phase to an aqueous medium was achieved by fluorocarbon oil evaporation or filtration followed by multiple sonication washes for ~10 minutes in deionized water (the washing fluid was exchanged 3-4 times). Sonication washing effectively removed any unpolymerized liquid fraction and surfactant from the polymerized droplet core. Conversely, fully polymerized particles retained their surfactant, creating hydrophobic surfaces that prevented dispersion into an aqueous phase. Fully polymerized particles were re-suspended in water by introducing a secondary aqueous-based surfactant (Pluronic® F-127 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA)). Re-suspension was achieved by implementing three consecutive water washes (containing ~4% wt. Pluronic® F-127) consisting of one minute pulsed vortexing of the particle solution and filter centrifugation for 2 minutes.

Numerical Model of Polymerization and Inhibition

A one-dimensional model of free radical hydrogel photopolymerization in the presence of oxygen was created to describe spatial and temporal states of PEG-DA within water-in-oil (WO) emulsion droplets. This model serves the need to quantify the competition between polymerization and oxygen inhibition within oxygen-supplying PDMS microfluidic devices. The model was built in the COMSOL multiphysics software package using assumptions and parameters described below. To visualize the model output we present one-dimensional concentration profiles, built upon a quadrant circle, representing a quarter of a droplet cross section from center to interface (Figure 2). Finite element analysis was performed over the area of the quarter circle, meshed into ~10,000 quadrilateral elements. Time dependent studies were performed using the Transport of Diluted Species COMSOL physics module. Total simulation times of 10 seconds with individual time steps of 0.1-1 seconds were used throughout the study, but were tuned to achieve solution convergence.

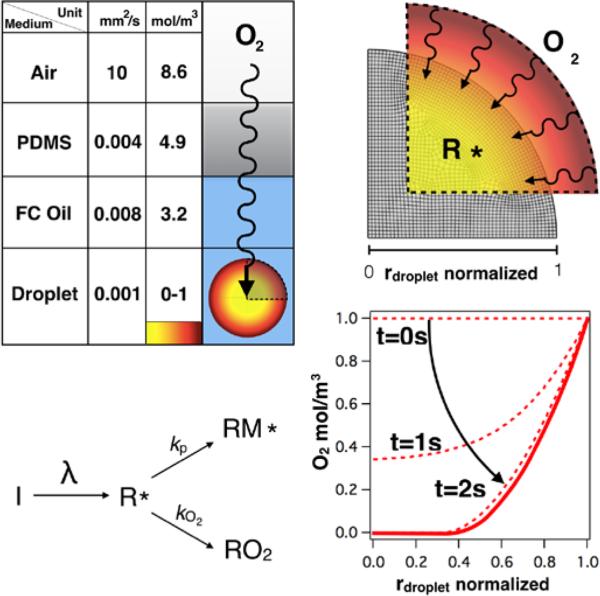

Figure 2.

Analysis of the effects of oxygen on PEGDA photopolymerization in microfluidic multiphase droplets under ambient atmosphere. Top-left corner: A summary of oxygen diffusivity and equilibrium concentration for each region of interest in the microfluidic droplet-generating device. Values are summarized from various literature sources10,54-58. A schematic illustration of oxygen transport from air into PDMS, through fluorocarbon oil, and into the microdroplet (not to scale) is shown. Given the absence of diffusion barriers, the concentration of oxygen in an un-purged device is not constrained until it reaches the microdroplet. In lower-left corner, a reaction schematic illustrates the polymerization reaction and rival initiator scavenging mechanism. In top-right, a meshed quadrant with a 1-D concentration overlay surface provides a representative oxygen concentration profile. On the bottom-right, a typical time dependent oxygen concentration profile in a microparticle of radius, r = 30 μm during course of polymerization. The model predicts that while photoinitator radicals quickly deplete oxygen initially present within the droplet, equilibrium is rapidly established by oxygen continuously diffusing from the oil phase.

Results and Discussion

Theory and Simulation

PEGDA photopolymerization begins with the photoactivation of an initiator, in which initiator molecules (I) absorb UV radiation, transforming into radical species (R). Subsequently, radical species are free to react with monomer (M) to initiate and propagate chain formation, or self-terminate via oxygen reaction (reaction schematic, Figure 2).

Due to high oxygen solubility and diffusivity in the fluorocarbon oil and PDMS respectively, the region surrounding droplets may be effectively considered to be an inexhaustible oxygen source. As a result, the oxygen concentration at the droplet boundary is assumed to be perpetually saturated. In an aqueous microdroplet, the nominal equilibrium solubility of oxygen (cO2) is ~1 mol/m3 and the rate of oxygen scavenging is initially five orders of magnitude larger than the rate of polymer propagation, thus polymerization will not proceed until oxygen is depleted10. Radicals are rapidly consumed by oxygen because the rate of the inhibitory reaction is much faster than that of polymerization (kO2[O2] >> kp [M]). Polymerization only proceeds once the respective rates of oxygen inhibition and on polymerization are equivalent, kO2 [O2] ~ kp [M]10.

Table 1 summarizes a reaction step sequence that is commonly used to describe free radical polymerization10,59,60 and has been implemented in this model. In step 1, a radical specie is formed, step 2 initiates the polymer chain formation with the radical specie, and step 3 is a propagation step during which polymerization takes place. Steps 4 and 5 are both considered termination steps in which radicals are either terminated by the oligomer chain reaction or oxygen inhibition.

Table 1.

Acrylate Polymerization Reaction Steps

| Step # | Reaction | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Initiator photolysis | |

| 2 | R * +M → RM * | Chain initiation |

| 3 | Chain propagation | |

| 4 | Chain termination | |

| 5 | Oxygen inhibition |

In this model the following set of ordinary differential equations were solved simultaneously:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

This system of equations describes the following physio-chemical fundamentals of PEGDA photopolymerization within an emulsion droplet. Equation 1 describes the decomposition of the photoinitiator at a rate constant kd, which depends on UV intensity [I], and the characteristic sample length. Because the diameter of droplets is less 100 μm, light passes through the particle essentially unattenuated and thus the energy-depth relationship is disregarded. The incident intensity [I] was measured directly using a radiometer. Equation 2 provides a molar balance of radical species via their formation and termination rates. The termination of radical species occurs in variety of ways, involving all possible combinations of active species formed during initiation and propagation steps (Table 1, steps 2-3). In our model we neglect complex multispecie termination mechanisms including radical trapping. Thus, all radical species (R*, RM*, RM*n+1) were lumped into a single radical quantity [X], where [X] terminates through a second order reaction with a previously established rate constant kt. Radical specie consumption by oxygen is also accounted for, where each oxygen molecule reacts with a single radical specie at a rate constant kO2. In balancing both [PI] and [R*] convective transport is neglected because [PI] is exposed and converted into radicals evenly across the droplet and [R*] is consumed much faster than it is transported. While it has been clearly established that recirculating three-dimensional flows do form in microdroplets as they flow through a microchannel61,62, it was assumed that these interior flows diminish with polymerization, and our experimental results validate this assumption. The oxygen specie balance equation (Equation 3) addresses two events: oxygen-radical scavenging and the diffusive oxygen flux into the droplet.

Equation 4 accounts for monomer [M] consumption or oligomer double bond conversion that drives polymerization. In calculating oligomer conversion, we neglect diffusion due to the macromer's large size and immobility, which are exacerbated as polymerization proceeds. Finally, ε is defined as the total fraction of converted oligomer (Equation 5), where aggregate gelation conditions can be evaluated within the droplet. It has been experimentally determined that gelation can occur at about 2% double bond conversion for multifunctional oligomers (e.g. PEG-DA)59,63. Others have proposed conversion requirements as high as 10% for gelation59. In our analysis we present a complete normalized conversion curve that does not regard fractional cut-off requirements. Gelation requirements tend to be incidental as our polymerized fraction curves display a characteristic stepwise profile with a clear distinction between the polymerized and unpolymerized regions of the droplet (Figure 3A). Our initial condition for the model is that at t=0, the entire droplet region is oxygen saturated. For boundary conditions, oxygen flux occurs at the droplet shell surface only, driven by the saturation limit, with no radial flux at the droplet center. Parameter values for modeling oxygen radical scavenging are found in the supplementary information.

Experimental

To examine the validity of our reaction diffusion model and establish baseline expectations for droplet polymerization behaviour, 40% PEGDA, 6% Irgacure 1173 aqueous solution droplets were polymerized within purged and non-purged (ambient oxygen) microfluidic channels. As previously discussed, Figure 3 A and B justify the use of fluorinated oil Novec 7500 – smaller droplets with narrower size distribution range is attained when employing comparable flow conditions (in this particular instance flow ratios of 3:1 μl/min, Oil: PEGDA solution were examined).

Summarized in Figure 3C, on-chip polymerization experiments reveal that the thickness of the unpolymerized shell, or the steady state polymerization inhibition zone, is constant across a range of droplet diameters. Additionally in Figure 3D, the intensity of UV light, serving as a proxy for the reaction rate, affects the relative portion of the droplet that is polymerized, allowing this fraction to be tuned over a wide range, up to 100% of the droplet diameter. These partial polymerization results are also predicted by the model and illustrate the need for oxygen purging - at zero nitrogen pressure (no purging), there exists an unpolymerized shell that will not vanish, even at extreme UV doses (e.g. 70 mW/cm2).

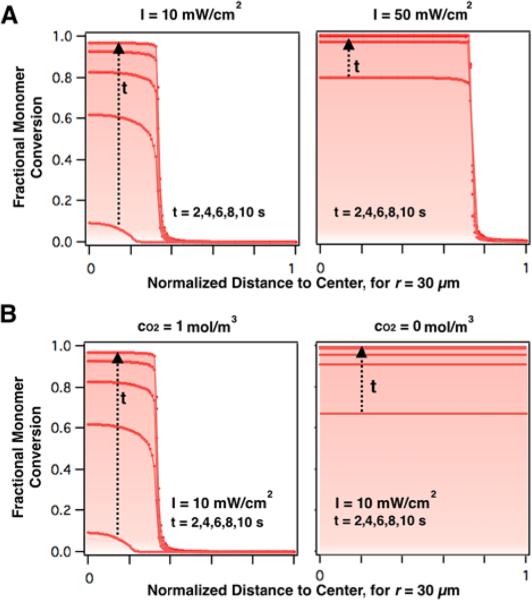

As observed experimentally and from the model, at the polymerization threshold, a sharp boundary occurs between the discrete polymerized fraction and the remaining liquid fraction. From the model, the boundary between these discrete fractions is characterized by a steep, step-like profile in the polymerized fraction curve (Figure 4 A).

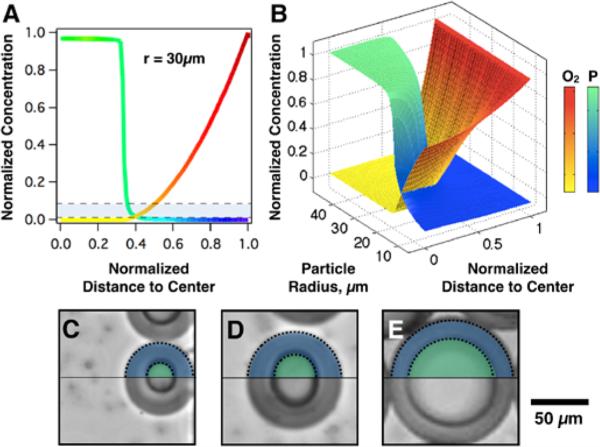

Figure 4.

Oxygen diffusivity sets the lower threshold for droplet polymerization in unpurged multiphase microfluidic devices. A: Polymerized PEGDA fraction, shown in green, strongly depends on diffused oxygen concentration (red) in a microdroplet (r = 30μm). As polymerization is impeded by dissolved oxygen, only a fraction of the droplet's radial volume is polymerized (~0.38) and the rest (~0.38 - 1) remains a liquid macromer (blue). The gray region represents minimum polymerization fraction values needed to observe gelation of the monomer solution59,63. B: A 3-D surface plot, compiled from a set of polymerization curves for particle radius in the range of r = 10-50 μm, illustrates a threshold for droplet polymerization at r < 20 μm. Confirmation of partially polymerized 40% PEGDA-700 particles are also shown in bright field microscope images (A: r ~30 μm, B: r ~50 μm, C: r ~60 μm). Images seen are partially over-layed with color to help visualize distinct polymerized and unpolymerized fractions.

Figure 4 shows micrographs of resulting partially polymerized particles consisting of two distinct fractions (Figure 4 C, D and E): a polymerized inner core (indicated by artificial green shading), and a uniform shell of unreacted monomer solution (blue shading). This observed scaling confirms modelling results that predict a polymerization threshold at a fixed distance from the droplet boundary.

By establishing the polymerization criteria at an upper bound of 10% double bond conversion59,63, the polymerized fraction remains relatively unchanged: 0.38 ±0.02 for 30 μm droplet (Figure 4 A, grey region), corresponding to a ~20 μm thick unpolymerized shell at the droplet interface closely matching our experimental result for this particular case. While the relative crosslinking fraction varies with droplet size, the absolute thickness of this unpolymerized zone is conserved, reinforcing that it is directly attributed to radial oxygen diffusion from the interface toward the droplet center (Figure 4B, red-yellow surface curve). The reaction-diffusion model predicts, and experimental results confirm a lower critical droplet radius of ~20 μm below which no polymerization would be observed for this particular combination of monomer solution (40% PEGDA, 6% Irgacure 1173), oil, device (oxygen un-purged device) and exposure intensity (10 mW/cm2). This close agreement between model and experiment indicates that these parameters govern polymerization and can be varied in our model to predict behaviour in any microfluidic particle synthesis process.

Additionally, partial droplet polymerization can provide control over particle size in the presence of oxygen-saturated materials. For instance, hydrogel particles may be fabricated at arbitrary length scales by photopolymerizing the droplet core provided the overall diameter is greater than the inhibition layer (40 μm under conditions used here).

The presented model can be used to predict both the thickness of the steady state unpolymerized zone as well as the time to reach steady state. Both of these results are a strong function of optical exposure intensity.

Figure 5A and 5B, compares the effect of increasing UV exposure intensity (10mW/cm2 to 50mW/cm2) to decreasing oxygen concentration (1mol/m3 to 0mol/m3) on transient and steady state polymerization profiles. These results confirm that by increasing UV intensity, the gelation time can be reduced and the unpolymerized droplet fraction can be decreased, but not fully eliminated. On the other hand, as shown in Figure 5B, the model predicts that with a nitrogen-jacketed device, and in the absence of a regenerative oxygen source, polymerization proceeds uniformly and completely across the droplet radius. As such, oxygen purging is the only effective approach to achieve full droplet polymerization without altering process parameters or the physio-chemical properties within of the particle (i.e. UV intensity, initiator concentration, or macromer concentration).

Figure 5.

A: Curves illustrating the fraction of polymerized PEGDA as a function of exposure time and intensity are shown for a model droplet (r = 30 μm). With increasing intensity, fractional polymerization curves shift right and the polymerized particle radius increases. Additionally, with increased UV intensity (A) these transient concentration profiles shift up as monomer double bond conversion accelerates relative to the rate of oxygen diffusion. (B) Model polymerization curves for an un-purged PDMS device (left) vs. oxygen-purged PDMS device (right) are shown for a model droplet. In the purged case, oxygen is uniformly consumed during polymerization, eliminating an unpolymerized region altogether.

Complete polymerization of droplets in the absence of oxygen provides a superior route to controlling particle morphology and the distribution of encapsulants within particles. Utilizing the micro-jacketed microfluidic device introduced here, we have polymerized a wide range of size and compositions of PEG-DA hydrogel microparticles. The reduction of oxygen by in situ nitrogen purging enables photopolymerization under significantly reduced macromer and initiator concentration, and UV dose. With nitrogen-jacketed devices, it is possible to produce PEG-DA microparticles in fluorocarbon oils with monomer compositions of 10%. As demonstrated, intensity and initiator concentration both play a significant role in microdroplet photopolymerization. As these two variables were increased, they were found to be equally effective at accelerating the rate of microparticle polymerization. In the radical specie formation component (Equation 2), UV intensity and initiator concentration are shown to be effectively inversely proportional. This assessment is reasonable, because photoinitiator species are in significant excess, and during UV exposure these species are converted and consumed at a very slow rate. In fact, only a small fraction of initiator (1-2%) is consumed over the entire polymerization period. This further implies that after the polymerization is complete, a large concentration of photoinitiator remains in the particle. From a functional biomaterial perspective, this is undesirable for applications in which cells are present because initiator cytotoxicity may persist long after polymerization is complete. Therefore, within reason, it may be preferred to increase the optical intensity while reducing initiator concentration.

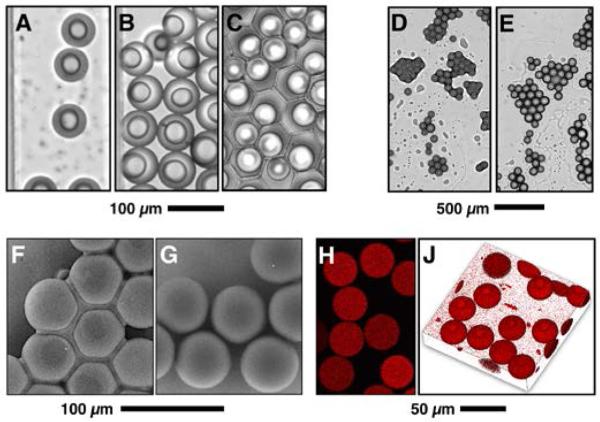

Additional distinctions between partially and fully polymerized particles are visually apparent in Figure 6. Partially polymerized particles may prove to be more desirable vehicles for certain biochemical applications due to the lack of residual surfactant upon their surface. Fully polymerized particles retain a fluorosurfactant layer, which renders particles hydrophobic and presents challenges to their re-suspension in aqueous solutions. With partially polymerized particles, it is possible to avoid surfactant retention altogether. It was found that after three water sonication washes, the surfactant-containing liquid oligomer film completely washed off partially polymerized particles, leaving clean surfaces that appear visually identical to fully polymerized particles. It was also observed that upon removal of the oil phase by volatilization (Figure 6 C, D, F), partially polymerized particles tend to form aggregates. Subsequently these particles were polymerized into ordered two-dimensional structures via a second UV exposure. Figure 6 (D, F) shows images of two-pass polymerization of partially polymerized particles held together by coalesced shells.

Figure 6.

Partially and fully polymerized particles can be produced in un-purged and oxygen-purged devices, respectively. A, B, and C display partially polymerized particles under flow, upon flow cessation, and upon oil drainage in a microfluidic device, respectively. Images D, E and F illustrate the effect of UV intensity upon polymerization. Upon particle recovery from the oil, a thin unpolymerized liquid fraction surrounds hydrogel spheres, holding particles together. Fully polymerized particles produced in N2 jacketed devices do not exhibit an unpolymerized liquid layer (G). Fully polymerized hydrogel particles marked with rhodamine acrylate have been also produced and imaged by confocal microscopy to confirm polymerization uniformity within particles. Image H and J show a cross sectional image and a three-dimensional stack image of fully polymerized particles, respectively. Confocal imaging confirms the localization of rhodamine within the particle by copolymerization, and therefore particle uniform polymerization.

Conclusions

In this work, we have fully described the photopolymerization of aqueous hydrogel forming solutions within microscale emulsion droplets. In particular, the inhibitory effects of oxygen upon microdroplet photopolymerization has been explored using a simple reaction-diffusion finite element model built with COMSOL multiphysics software. It was found that oxygen inhibition introduces a system-dependent length scale threshold below which polymerization is completely prohibited. To overcome this limit, and enable continuous PEG-DA microgel production on a chip, a nitrogen-jacketed microfluidic device for in situ oxygen purging has been developed and introduced. This platform allows the facile fabrication of monodisperse PEG-DA microparticles in large quantities. Mild polymerization conditions and cytocompatible droplet compositions have been successfully employed, indicating that this approach may be extended to the production of functional biomaterials. With the device and predictive model described here, one may completely define droplet photopolymerization, allowing for complete or partial polymerization of PEG-DA droplets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank D. Li, D. Debroy and B. Noren in the Chemical Engineering Department at the University of Wyoming for their critical reading of the manuscript and useful suggestions.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Program (BBBE 1254608) and the NIH-funded Wyoming IDeA Networks of Biomedical Research Excellence program (P20RR016474 and P20GM103432).

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [Parameters for modeling oxygen radical scavenging resource table]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

References

- 1.Mark HF. Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology, Concise. Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders KJ. Organic Polymer Chemistry. Springer; Netherlands, Dordrecht: 1988. pp. 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burkoth AK, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2000;21:2395–2404. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metters AT, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:7043–7049. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu Q, Nauman S, Santerre JP, Zhu S. Journal of Materials Science. 2001;36:3599–3605. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawhney AS, Pathak CP, Hubbell JA. Macromolecules. 1993;26:581–587. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen KT, West JL. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4307–4314. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mequanint APAK. 2011. pp. 1–22.

- 9.Billiet T, Vandenhaute M, Schelfhout J, Van Vlierberghe S, Dubruel P. Biomaterials. 2012:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decker C, Jenkins A. Macromolecules. 1985;18:1241–1244. [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien AK, Bowman CN. Macromol. Theory Simul. 2006;15:176–182. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ligon SC, Husár B, Wutzel H, Holman R, Liska R. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:557–589. doi: 10.1021/cr3005197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryant SJ, Nuttelman CR, Anseth KS. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2000;11:439–457. doi: 10.1163/156856200743805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rice MA, Anseth KS. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2004;70A:560–568. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann BK, Gobin AS, Tsai AT, Schmedlen RH, West JL. Biomaterials. 2001;22:3045–3051. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford MC. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:2512–2517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burdick JA, Anseth KS. Biomaterials. 2002;23:4315–4323. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mooney R, Haeger S, Lawal R, Mason M, Shrestha N, Laperle A, Bjugstad K, Mahoney M. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2011;17:2805–2815. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicodemus GD, Bryant SJ. Tissue Engineering Part B: Reviews. 2008;14:149–165. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2007.0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu J. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4639–4656. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloxin AM, Kasko AM, Salinas CN, Anseth KS. Science. 2009;324:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1169494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pregibon D, Toner M, Doyle P. Science. 2007;315:1393. doi: 10.1126/science.1134929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsu MN, Luo R, Kwek KZ, Por YC, Zhang Y, Chen C-H. Biomicrofluidics. 2015;9:052601–8. doi: 10.1063/1.4916230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panda P, Ali S, Lo E, Chung BG, Hatton TA, Khademhosseini A, Doyle PS. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1056. doi: 10.1039/b804234a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sebra RP, Masters KS, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. Langmuir. 2005;21:10907–10911. doi: 10.1021/la052101m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li CY, Wood DK, Hsu CM, Bhatia SN. Lab Chip. 2011;11:2967–9. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20318e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burdick JA, Mason MN, Anseth KS. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2001;12:1253–1265. doi: 10.1163/156856201753395789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin C-C, Anseth KS. Pharm Res. 2008;26:631–643. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9801-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dendukuri D, Gu SS, Pregibon DC, Hatton TA, Doyle PS. Lab Chip. 2007;7:818. doi: 10.1039/b703457a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suh SK, Bong KW, Hatton TA, Doyle PS. Langmuir. 2011;27:13813–13819. doi: 10.1021/la202796b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Appleyard DC, Chapin SC, Srinivas RL, Doyle PS. Nature Protocols. 2011;6:1761–1774. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis CL, Lin Y, Yang C, Manocchi AK, Yuet KP, Doyle PS, Yi H. Langmuir. 2010;26:13436–13441. doi: 10.1021/la102446n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang DK, Oakey J, Toner M, Arthur JA, Anseth KS, Lee S, Zeiger A, Van Vliet KJ, Doyle PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4499–4504. doi: 10.1021/ja809256d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H, Li J, Zhou W, Pelan EG, Stoyanov SD, Arnaudov LN, Stone HA. Langmuir. 2014;30:4262–4266. doi: 10.1021/la5004929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koh CG, Kang X, Xie Y, Fei Z, Guan J, Yu B, Zhang X, Lee LJ. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2009;6:1333–1342. doi: 10.1021/mp900016q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calvör A, McIller BW. Pharmaceutical Development and Technology. 1998;3:297–305. doi: 10.3109/10837459809009857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu S, Nie Z, Seo M, Lewis P, Kumacheva E, Stone HA, Garstecki P, Weibel DB, Gitlin I, Whitesides GM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:724–728. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landfester K, Musyanovych A. Chemical Design of Responsive Microgels. Vol. 234. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2010. pp. 39–63. Berlin, Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed EM. Journal of Advanced Research. 6:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sivadas N, Cryan S-A. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2011;63:369–375. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliveira MB, Mano JF. Biotechnol Progress. 2011;27:897–912. doi: 10.1002/btpr.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hazel J, Krutkramelis K, Mooney P, Tomschik M, Gerow K, Oakey J, Gatlin JC. Science. 2013;342:853–856. doi: 10.1126/science.1243110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Tsang V, Bhatia SN. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2004;56:1635–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Olabisi RM, Lazard ZW, Franco CL, Hall MA, Kwon SK, Sevick-Muraca EM, Hipp JA, Davis AR, Olmsted-Davis EA, West JL. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2010;16:3727–3736. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Geest BG, Urbanski JP, Thorsen T, Demeester J, De Smedt SC. Langmuir. 2005;21:10275–10279. doi: 10.1021/la051527y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwang CM, Sim WY, Lee SH, Foudeh AM, Bae H, Lee S-H, Khademhosseini A. Biofabrication. 2010;2:045001–045001. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/2/4/045001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuck L, Taylor A. Biotech. 2008;45:179–186. doi: 10.2144/000112889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamilton SK, Bloodworth NC, Massad CS, Hammoudi TM, Suri S, Yang PJ, Lu H, Temenoff JS. Biotechnology journal. 2013;8:485–495. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nair JR, Chiappone A, Destro M, Jabbour L, Meligrana G, Gerbaldi C. Membranes. 2012;2:687–704. doi: 10.3390/membranes2040687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitesides G. Annual review of materials science. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duffy D, Schueller O, Brittain S, Whitesides G. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering. 1999;9:211. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holtze C, Rowat AC, Agresti J, Hutchison JB, Angilè FE, Schmitz CHJ, Köster S, Duan H, Humphry KJ, Scanga RA, Johnson JS, Pisignano D, Weitz DA. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1632. doi: 10.1039/b806706f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brouzes E, Medkova M, Savenelli N, Marran D, Twardowski M, Hutchison JB, Rothberg JM, Link DR, Perrimon N, Samuels ML. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:14195–14200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903542106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.An HZ, Safai ER, Burak Eral H, Doyle PS. Lab Chip. 2013;13:4765–4774. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50610j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cox ME, Dunn B. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 1986;24:621–636. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vermuë M, Tacken M, Tramper J. Bioprocess Engineering. 1994;11:224–228. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang X, Zheng B. Analyst. 2011;136:1222–1226. doi: 10.1039/c0an00913j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abbyad P, Tharaux P-L, Martin J-L, Baroud CN, Alexandrou A. Lab Chip. 2010;10:2505–9. doi: 10.1039/c004390g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dendukuri D, Panda P, Haghgooie R, Kim JM, Hatton TA, Doyle PS. Macromolecules. 2008;41:8547–8556. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jariwala AS, Ding F, Boddapati A, Breedveld V, Grover MA, Henderson CL, Rosen DW. Rapid Prototyping Journal. 2011;17:168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grigoriev RO, Schatz MF, Sharma V. Lab Chip. 2006;6:1369–1372. doi: 10.1039/b607003e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ma S, Sherwood JM, Huck WTS, Balabani S. Lab Chip. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1039/c4lc00671b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Andrzejewska E. Progress in Polymer Science. 2001;26:605–665. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.