Abstract

Gene Ontology1 and similar biomedical ontologies are critical tools of today genetic research. These ontologies are crafted through a painstaking process of manual editing, and their organization relies on the intuition of human curators. Here we describe a method that uses information theory to automatically organize the structure of GO and optimize the distribution of the information within it. We used this approach to analyze the evolution of GO, and we identified several areas where the information was suboptimally organized. We optimized the structure of GO and used it to analyze 10,117 gene expression signatures. The use of this new version changed the functional interpretations of 97.5% (p < 10-3) of the signatures by, on average, 14.6%. As a result of this analysis, several changes will be introduced in the next releases of GO. We expect that these formal methods will become the standard to engineer biomedical ontologies.

Every year, over 400,000 new articles enter the biomedical literature2, creating an unprecedented corpus of knowledge that is impossible to explore with traditional means of literature consultation. This situation motivated the development of biomedical ontologies, structured information repositories that organize biomedical findings into hierarchical structures and controlled vocabularies. Gene Ontology (GO) is arguably the most successful example of a biomedical ontology. GO is a controlled vocabulary to describe gene and gene product attributes in any organism, and includes 26,514 terms organized along three dimensions: molecular function, biological process, and cellular component. GO has become even more intensively used with the introduction of high-throughput genomic platforms because of its ability to categorize large amounts of information using a controlled vocabulary to group objects and their relationships1,3–4.

Today, GO and other biomedical ontologies are the result of a painstaking, costly, and slow process of manual curation that requires reaching a consensus among many experts to implement a change. Furthermore, the topology of GO has become critically important since the introduction of gene set enrichment methods. These methods have allowed investigators to characterize the results of a high-throughput experiment in terms of coherent, knowledge-defined, sets of genes – such as pathways, functional classes, or chromosomal locations – rather than in terms of anecdotal evidence about single genes5–6. GO has become a primary provider of these gene sets and researchers use its graphical structure to identify the specificity of a gene class, so that they will compare classes of the same specificty7. Previous studies have found that the structure of GO does not conform to expected intuitions regarding the structure and distributions of ontology terms8,9. Gene enrichment methods typically use the structure of ontologies as a proxy for the specificity of a term10,11 or, in some cases, use automated procedures to identify structural biases and to compensate for for them in the analysis7–8,12. Unfortunately, in some cases, even these compensative methods are unable to reach the same conclusions of a well-calibrated ontology (Supplementary Information S8).

The approach we advocate here tries to solve the problem at its root by optimizing the structure of the ontology so that it will indeed be an accurate representation of the informational specificity of any term in the ontology. This approach would not only avoid the necessity to compensate for biases but improve the semantic transparency of the ontology structure. To do so, we introduce an automated method for engineering the structure of GO based on the information content of each single term. The intuition behind this method is that ontologies are information systems and, as such, they can be optimized using the well established mathematics of information theory. Given its mathematical nature, this optimization process can be automated, thus producing a principled and scalable architecture to engineer GO and, analogously, other biomedical ontologies.

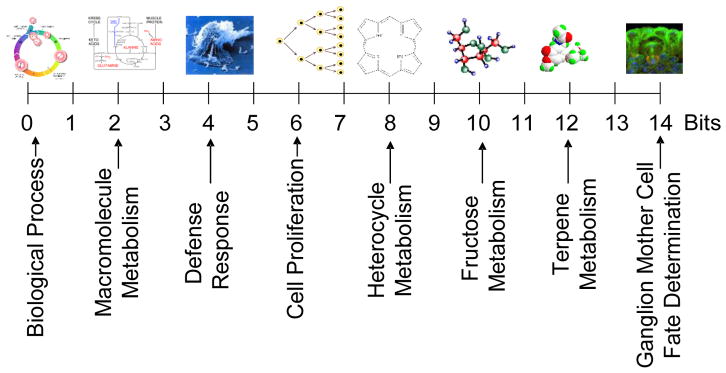

Our approach starts from the quantification of information contained in the terms of the ontology. The information content of a term is computed from the amount of annotation available for it relative to all other terms and it is a measure of the surprise caused by labelling a gene with this term rather than with any other term (Supplementary Information S1). For instance, if a term contains all genes, then it is not surprising for a given gene to be labelled with it, so this term does not contain much information. Thus, the more genes or gene products associated with a term, the less specific the term is and the less information is conveyed by it. This “surprise factor” is called “self-information”, and information theory provides a formal definition for it13 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Spectrum of GO terms: examples ranging from 1 to 14 bits

Using information theory, we analyzed the evolution of the information content of GO across time, examining 2 million genes across all the organisms encoded in the ontology annotations. This process highlighted information biases and inefficiencies that may affect the usage of GO, and identified those areas of the ontology that were sub-optimally organized. This analysis identified three types of information inefficiencies in the structure of GO.

The first type of inefficiency arises from the variability of the information content among the terms within a given ontology level. By the principle of maximum entropy, an even a priori distribution of information (where all terms in a level are equally specific and hence equally informative) is most efficient, since a random experiment is most informative if the probability distribution over outcomes is uniform13. Furthermore, gene set enrichment methods often use GO level (i.e., distance from the top of the graph) as a proxy for degree of specificity10,7,11; this strategy implicitly relies on within-level uniformity of information content. Optimally, then, all the terms in a given level would have equal specificity and, therefore, the same information content. Our analysis revealed that the original version of GO contained a large degree of such intra-level variability of information content. For example, the term “pilus retraction” was originally at level 2, at the same level of terms like “cell cycle” and “cell development” that are actually much more general.

The second type of structural inefficiency, inter-level variability, arises from deviations in information content between levels. In general, terms become more specific as the information content of a level increases with depth in the graph. In some areas of GO, however, the mean information content decreases from one level to the next, creating an information bottleneck. In this case, most of the annotation information of the previous level is transmitted to the next through only a few terms. The larger the decrease in information content, the more severe the bottleneck. The presence of these areas of suboptimal information distribution violate the assumption of gene set enrichment analysis methods7,12 that the specificity in GO terms effectively increases from one level to the next (Supplementary Information S2).

The third type of structural inefficiency, topological variability, arises from the suboptimal organization of the branches. The principle of maximum entropy dictates that the closer a topological structure is to uniform, the greater is the information that experiments can derive from it8. We used entropy rate to quantify the uniformity of the GO branch structure (Supplementary Information S3), so that a higher entropy rate indicates that the ontology structure is closer to uniform.

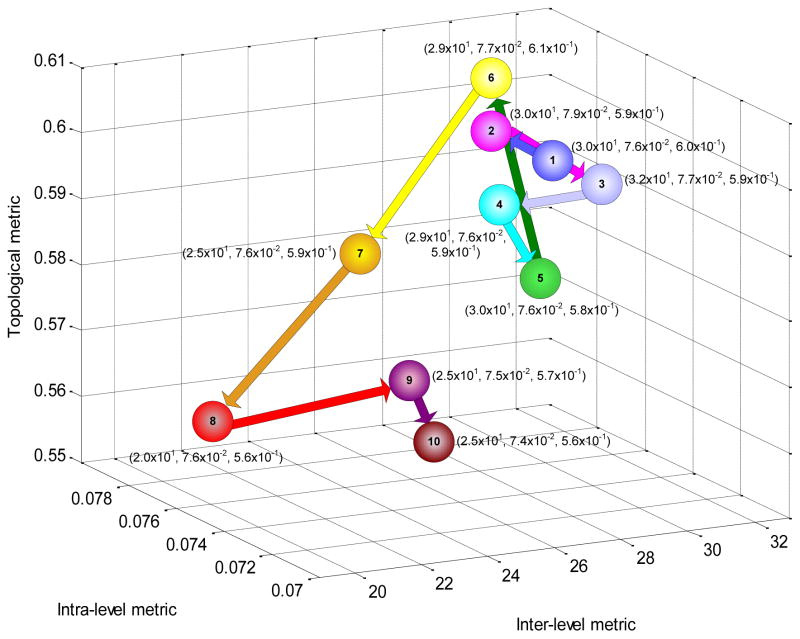

We analyzed the evolution of GO along these three dimensions of structural inefficiency using ten releases of GO containing over two million unique genes14. Figure 2 plots their structural inefficiencies for each release of GO and illustrates how they have been decreasing over time (Supplementary Information S4). For instance, with time point 8 (February 1, 2007), inter-level variability and topological variability saw substantive improvements, coinciding with introduction of the “is_a complete” property in GO15. In contrast, intra-level variability saw comparatively modest improvements over the evolution of GO.

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional evolution of GO over ten releases from 2005 to 2007 along the three dimensions of structural inefficiency. An ontology with no inefficiency across these metrics would be at the origin (0,0,0).

One of the greatest dangers of structural inefficiencies in GO is the impact they can have on the functional interpretation of the results of high-throughput experiments. We thus optimized the information distribution of GO by introducing single level changes and modifying 1,001 relationships and 11% percent of GO terms, thus significantly improving the overall intra-variability (p < 10−3) (Supplementary Information S5).

We used this optimization method to create a modified, improved GO and we compared it to the current GO in the interpretation of 10,117 gene expression signatures from DNA microarray experiments16. Each signature contains genes differentially expressed between two biological conditions, and we compared the results of gene enrichment analysis of these signatures obtained by the original and the modified GO. We found that these changes significantly impacted the functional interpretations of 97.5% (p < 10−3) of the experimental gene signatures, and altered the resulting set of GO categories by 14.6% on average (Supplementary Information S6). Based on this analysis, we presented fourteen recommendations to the GO Consortium and most of these new annotations (twelve) will be introduced in the next release of GO (Supplementary Information S7).

Finally, as a result of our analysis, we applied this approach to more complicated multi-level structural changes. We suggested to the GO Consortium to move twelve terms. They all underwent the standard curatorial validation of the GO consortium and eleven of them are now included in the current release of GO. The twelfth term, pigmentation (GO:0043473) had few annotations at the time, but was not moved as it was expected that many more genes would be annotated with that term in the future. The most striking result of this experiment was to show the convergence of mathematical optimality and biological validity and that a formal, automated analysis was able to uncover sound biological information hidden in the structure of the ontology. By altering the ontology itself, our approach improves gene enrichment results in ways that cannot be obtained by simply changing the underlying gene enrichment method (Supplementary Information S8).

This analysis reveals that GO contains more information than we currently use. By optimizing the distribution of information within GO, our method can be used to aid the design of more efficiently organized knowledge repositories — leading to a more effective use of biological information. This method is already being used to this aim by the GO Consortium and other ontologies, such as the Phenotypic quality ontology (PATO)17 in the OBO Foundry18. We expect that formal and automated methods will become the standard for the engineering of biomedical ontologies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Library of Medicine (NLM/NIH) under grants 1K99LM009826 and 5T15LM007092, and by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI/NIH) under grants 2P41HG02273, 1R01HG003354, and 1R01HG004836. The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions.

References

- 1.Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis DA, Ciurea I, Flanagan TM, Perrier L. Solving the information overload problem: a letter from Canada. Med J Aust. 2004;180:S68–71. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb05952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camon E, et al. The Gene Ontology Annotation (GOA) Database: sharing knowledge in Uniprot with Gene Ontology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D262–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris M, et al. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D258–D261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doniger SW, et al. MAPPFinder: using Gene Ontology and GenMAPP to create a global gene-expression profile from microarray data. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Shahrour F, Diaz-Uriarte R, Dopazo J. FatiGO: a web tool for finding significant associations of Gene Ontology terms with groups of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:578–80. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alterovitz G, Xiang M, Mohan M, Ramoni MF. GO PaD: the Gene Ontology Partition Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D322–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogren PV, Cohen KB, Hunter L. Implications of compositionality in the gene ontology for its curation and usage. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2005:174–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennis G, Jr, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou M, Cui Y. GeneInfoViz: constructing and visualizing gene relation networks. In Silico Biol. 2004;4:323–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raychaudhuri S, Chang JT, Sutphin PD, Altman RB. Associating genes with gene ontology codes using a maximum entropy analysis of biomedical literature. Genome Res. 2002;12:203–14. doi: 10.1101/gr.199701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacKay DJC. Information theory, inference, and learning algorithms. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, U.K.; New York: 2003. p. xii.p. 628. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu CH, et al. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt): an expanding universe of protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D187–91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Gene Ontology project in 2008. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D440–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Y Yi, CLC, Miller AL. George. Strategy for encoding and comparison of gene expression signatures. Genome Biology. 2007;8 doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-7-r133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gkoutos GV, et al. Ontologies for the description of mouse phenotypes. Comp Funct Genomics. 2004;5:545–51. doi: 10.1002/cfg.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith B, et al. The OBO Foundry: coordinated evolution of ontologies to support biomedical data integration. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1251–5. doi: 10.1038/nbt1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.