Abstract

2.3-month-old (Case 1), one-month-old (Case 2) and 6-month-old (Case 3), Japanese Black calves presented with mild to severe wheezing. All calves had histories of dystocia at birth with breech presentation. Physical examination, thoracic radiography, endoscopy or computed tomography indicated wheezing associated with tracheal collapse and stenosis caused by perinatal rib fractures. Partial resection of the fractured first and second ribs was performed on all calves. The respiration in Cases 1 and 2 immediately improved after the surgery, while Case 3 required two weeks to improve. Cases 1 and 3 grew up healthy and were sold at auction, but Case 2 had a recurrence of wheezing at three months post-discharge and showed growth retarding. Partial costectomy may be an effective solution for control of respiration, however, further cases are required to discuss the criteria for surgical management and to obtain favorable postoperative prognosis in calves with tracheal collapse and stenosis caused by perinatal rib fractures.

Keywords: calf, partial costectomy, perinatal rib fracture, tracheal collapse and stenosis, wheezing

Rib fractures have been known to occur in calves during delivery, sometimes causing perinatal death [14]. Although pathogenesis has been unclear, fractures are suspected to be related to dystocia at birth, especially with breech presentation or excessive traction [4, 5, 12, 17]. The most involved bones are cranial pairs [4, 5, 12, 17], but multiple rib fractures can be also produced [1]. As a result of the fracture and following callus formation, the trachea at the thoracic inlet becomes collapsed and stenotic [4, 12]. Clinical signs in previous reports have included wheezing, cough, dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, exercise intolerance and growth retarding [4, 12, 17].

Supportive treatments and tracheotomy are not effective in this disorder [17]. Although treatments are not necessary in some calves with fractures, almost all calves with this respiratory problem require surgical intervention to improve the condition [5, 17]. Extra- or intra-luminal stent therapies for tracheal collapse have been well known in canine patients [10]. In farm animals with the condition, hand-made extra-luminal prosthesis, open-ended coil spring or made from polypropylene syringe, has been also applied for surgical correction [3, 7, 11, 13]. Calves with the disease caused by rib fractures have also received the surgery [4, 5, 12], but prognosis has been relatively poor [4, 5, 12, 17]. In addition, the prosthesis requires removal after a few months post-correction, because it becomes unsuitable to the trachea size due to growth of the calf [4, 5, 12].

The authors encountered three calves with mild to severe wheezing caused by rib fractures; partial costectomy provided successful management of the respiration. This paper describes the clinical findings of three Japanese Black calves with stridor caused by perinatal rib fracture that were treated with partial costectomy.

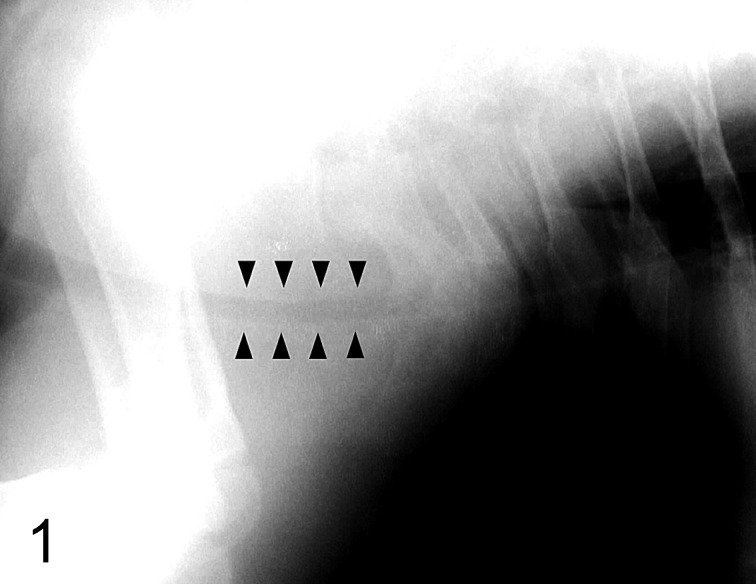

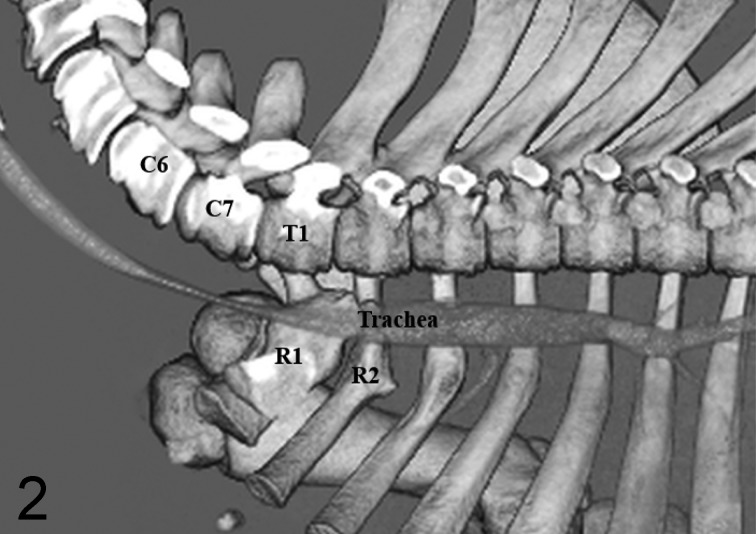

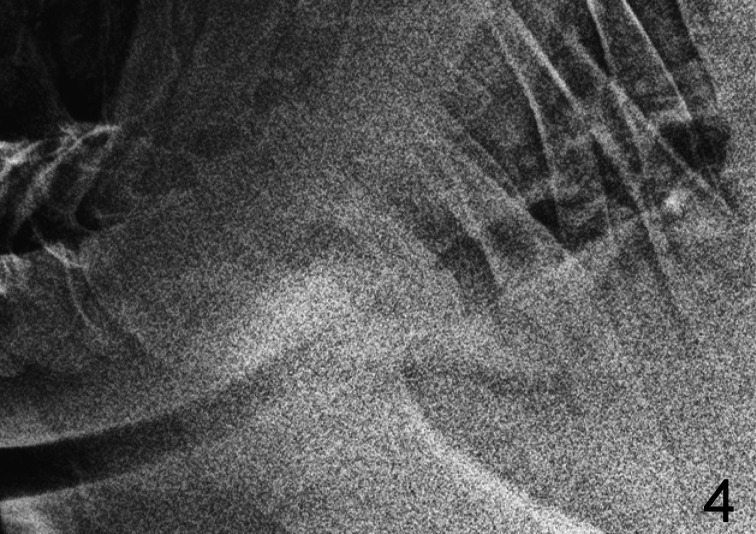

Case 1: A 2.3-month-old, male, Japanese Black calf, weighing 85 kg, presented with dyspnea after excitement and exercise. This calf had been delivered by forced extraction, because of excessively fetus and breech presentation. The calf had no respiratory signs at rest, but showed respiratory rate 60 breath / min at excite. Physical examination revealed the left side of the chest wall depressed towards the thoracic cavity and a roll sound at the cervical trachea, which was strongest in the thoracic inlet region. In this case, radiographies showed tracheal collapse and stenosis at the posterior cervix (C6) to thoracic inlet region (T1), approximately 10 cm in width forward of cranial edge of the first rib and marks of cranial rib fractures (Fig. 1). There were no findings of pneumonia. Following xylazine (Bayer, Tokyo, Japan) sedation (0.2 mg/kg, IV) and insertion of a tracheal tube, computed tomography (CT) (Toshiba Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan) was performed under general anesthesia of isoflurane (DS Pharma Animal Health, Osaka, Japan) with oxygen. The results demonstrated the marks of fractures of the left first to third ribs and right first and second ribs, and the left cranial two pairs encroached on the thoracic cavity. In addition, three-dimensional reconstruction images of CT also recognized tracheal collapse and stenosis at the sixth cervical to first thoracic vertebrae (Fig. 2). On the basis of these clinical findings, respiratory sign in this calf was diagnosed as being caused by tracheal collapse and stenosis resulting from rib fractures. Resection of the marked, deformed, left first and second ribs was performed in this case. The calf was anesthetized, following the same procedures as for the CT examination. The calf was positioned at the right lateral recumbency with lifting up the left forelimb, and the left first and second ribs were approached through the axillary area (Fig. 3). After skin incision, the superficial and deep pectoral muscles were cut. The first and second deformed ribs were immediately palpable, and connective tissue was bluntly dissected. Partial costectomy was performed in the deformed parts of the ribs by using an electrical saw. Following the costectomy, the muscles were sutured to close the defect in the thoracic wall, and the surgery was finished. The surgery time was approximately 3.5 hr. There were no peri- and post-operative complications in this case. Respiratory sign did not develop after excitement and exercise, postoperatively. Enrofloxacin (Bayer, 5 mg/kg, SC) and flunixin meglumine (Intervet K.K., Tokyo, Japan, 2 mg/kg, IV) were administered for six days and for three days, respectively. The calf was discharged six days post-operation. Radiography confirmed no problems of the tracheal airway 41 days after the surgery (Fig. 4). Thereafter, the calf grew up healthy and was sold at auction.

Fig. 1.

Radiophotograph of Case 1, showing tracheal collapse and stenosis at posterior cervix to cranial thoracic inlet (arrowheads) and marks of fractures in a few ribs.

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional reconstruction image of CT in Case 1, showing tracheal collapse and stenosis at the sixth cervical to first thoracic vertebrae (left lateral view after removal of left scapular, forelimb and ribs). Fractured marks are also recognized in the right first (R1) and second (R2) ribs. C6: sixth cervical vertebra, C7: seventh cervical vertebra, T1: first thoracic vertebra.

Fig. 3.

Position at surgery in Case 1, showing right lateral recumbency with left forelimb lifted for axillary approach to the left first and second ribs. A skin incision was made along the white dotted line.

Fig. 4.

Radiophotograph of Case 1, showing no troubles in tracheal air way 41 days after partial costectomy.

Case 2: A one-month-old, male, Japanese Black calf, weighing 65 kg, presented with wheezing and dyspnea. This case also had a history of dystocia, as a result of the caudal presentation and an adipose lump at the pelvic cranial part of the mother. Sixteen days after birth, the calf developed a fever and decreased suckling. Antibiotics administration resolved the fever, but wheezing and labored breathing persisted. At the first presentation in our university, the calf showed prominent wheezing and abdominal breathing indicating dyspnea at rest. Auscultation revealed no abnormalities in the heart and lungs. Palpation detected decompression of the right chest wall. Radiographies of the cervix and thorax demonstrated marks of multiple rib fractures and severe tracheal collapse and stenosis at the caudal cervix (C7) to thoracic inlet region (T1), approximately 9 cm in width forward of cranial edge of the first rib. In this case, the tracheal lesion was more severe than in Case 1. There were also no findings of pneumonia. In this case, endoscopic observation (OLYMPUS, Tokyo, Japan) of the trachea was performed with xylazine (Bayer) sedation (0.2 mg/kg, IV), and tracheal stenosis was observed in the lumen because of the perforated dorsal wall of the trachea at the cervical area. In this calf, partial resection of the fractured ribs was also performed in the right first and second ribs, similar to procedures with Case 1. After removal, the stenosis lesion of the trachea was visibly dilated by the cuff of the tube. A drain was placed in the thorax, and the chest wall was closed. The surgery time was approximately 3 hr. There were no troubles observed from the anesthesia. The respiratory distress in this calf was dramatically improved the next day, despite insufficient expansion of the tracheal airway in radiographies. Although knuckling of the right forelimb indicating radial nerve paralysis had developed, paralysis resolved one week later. Postoperative medication including enrofloxacin (Bayer, 5 mg/kg, SC) for nine days and flunixin meglumine (Intervet K.K., 2 mg/kg, IV) for four days was administered. Suckling and activity recovered, and the calf discharged at day nine post-operation. Thereafter, the calf had a favored course with good condition. However, the calf showed growth retarding compared to calves of similar age at the farm, and wheezing recurred three months after discharge. Therefore, the calf went to slaughter.

Case 3: A six-month-old, castrated male, Japanese Black calf, weighing 201 kg, presented with mild wheezing after excitement and feeding. This calf also had been delivered by forced extraction because of dystocia caused by a posterior presentation, and the animal immediately showed dyspnea at birth. Supportive treatments including fluid therapy and steroid and antibiotics injections were performed, but wheezing did not completely diminish. The suspected cause of wheezing was perinatal rib fracture, and the owner eagerly wanted us to deaden or reduce it to allow the calf to be sold at auction. Respiratory sign was uncertain at rest, but auscultation suggested that a roll sound was maximum at the thoracic inlet. Cervical palpation induced coughing. The right thoracic wall in the axillary area was slightly decompressed, and the severity was less than in Cases 1 and 2. There were no abnormal findings in the lung and heart sound. On the basis of these findings, this case was also tentatively diagnosed with tracheal collapse and stenosis due to cranial rib fractures. CT (Toshiba) examination was performed under general anesthesia, the same as with Case 1. CT images demonstrated that the right first and second ribs were deformed and slightly encroached upon the thoracic cavity, and the trachea was collapsed and stenotic at sixth to seventh cervical vertebrae. Partial costectomy of the right first and second ribs was performed with a different approach from those in Cases 1 and 2. The calf was positioned in left lateral recumbency, and the right forelimb was taken in tow backward (Fig. 5). A skin incision was made at the cranial line of the scapula and the scapular joint. The ribs were approached and palpable after medial incision of the brachiocephalic muscle. With careful manipulation of the brachial plexus, the scalenus dorsalis muscle and surrounding connective tissues were separated to make the ribs visible. The axillary artery was injured from this procedure, resulting in severe hemorrhage. Although extensive time was required for hemostasis, it was successfully done. Fractured ribs with deformity were confirmed by palpation, and the deformed parts were partially resected with an electrical saw. After rib removal, the muscles were sutured to cover the defect, and surgery was finished. The surgery time was approximately 4.5 hr. The next day, knuckling in both forelimbs indicating radial nerve paralysis had developed, but paralysis of the left side improved one week post-operation. However, the surgery side required approximately three weeks for improvement. Antibiotics, benzyl-penicillin procaine/dihydrostreptomycin sulfate solution (Meiji Seika Pharma Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, 10,000 U/kg, 12.5 mg/kg, IM) or enrofloxacin (Bayer, 5 mg/kg, SC), were administered for twelve days post-surgery. Wheezing did not improve immediately, but diminished gradually within two weeks. The calf discharged 22 days after surgery and had no problems with gait or wheezing on the farm. Thereafter, the calf grew normally and went up for auction.

Fig. 5.

Position at surgery in Case 3, showing left lateral recumbency and caudal traction of the right forelimb for approach to the right first and second ribs via the cranial part of the scapula and shoulder joint. A skin incision was made along the white dotted line.

In this report, all three calves with stridor were improved by partial costectomy, and it indicated the respiratory disorder was related to perinatal rib fractures leading to tracheal airway abnormality. However, Case 2 had recurrent wheezing three months post-operation and retarded growth for unknown reasons.

Previous reports regard tracheal collapse and stenosis in calves as a congenital disease or traumatic malformation [2, 7, 9, 11, 15, 16]. However, the major etiology of the condition is associated with rib fractures [4, 12, 17]. Diagnosis of this disease due to rib fracture requires a history of dystocia at birth with breech position or forced extraction, verified through physical examination, radiography and endoscopy [12, 17]. This respiratory condition is similar to those of other upper or lower airway diseases, and clinicians may misdiagnose affected calves with bronchopneumonia and necrotic laryngitis if they do not know of the disease [17]. Palpation may detect imbalance of the right and left thoracic walls at the axillary part and rib deformities by callus formation [4, 12]. A thrill of the stridor at the cervical trachea was also palpable in our calves. In addition, auscultation would be useful in the diagnosis [12, 17]. In Cases 1 and 3, an abnormal respiratory sound was auscultated at the cervical trachea with maximum volume at the thoracic inlet, even when they were asymptomatic at rest. Definitive diagnosis depends on radiographies in calves with marks of rib fractures and tracheal collapse and stenosis [12, 17]. In Cases 1 and 2, radiographical examination was performed, and the results also showed evidence of several rib fractures and tracheal collapse and stenosis. In Case 3, radiographical changes were estimated to be uncertain, and examination was not performed. CT examinations were performed in Cases 1 and 3, and the findings, especially three-dimensional reconstruction images, were suitable to evaluate the severity of rib fractures and tracheal lesion and to schedule surgical strategies. Although the use would be limited in bovine clinic, CT examination should be included in the diagnostic option of the disease in calves. Endoscopy can also observe tracheal collapse and stenosis from the inside. Upon examination, the perforated dorsal wall of the cervical trachea could be observed in Case 2. However, endoscopy may not be always useful for diagnosis [12].

In calves with tracheal collapse and stenosis due to rib fracture, prostheses have been utilized in surgical management [4, 5, 12]. In the present cases, partial resection of deformed ribs led to improvement of stridor. Our result suggests that prostheses are not always necessary for treatments of tracheal collapse and stenosis by perinatal rib fractures in calves. The improvement of wheezing required two weeks in Case 3, but immediately recovered in Cases 1 and 2 after surgery. The improvement of respiration after the surgery may depend on the duration of involvement, because Case 3 received surgery at six months of age.

Two approach methods for the first and second ribs were tried in our calves. In Cases 1 and 2, the ribs were approached via the axillary area. On the other hand, in Case 3, the ribs were explored via the cranial area of the scapula and the joint with posterior extraction of the forelimb. Careful approach and resection of the ribs were required in both methods, because the brachial plexus and axillary artery are present around the first rib [8]. In Cases 2 and 3, radial nerve paralysis developed as a post-operative complication. Although there have been no reports describing the complication, our experiences advise more careful approach and manipulation for resection of first and second ribs. In addition, in Case 3, the axillary artery was injured when muscle and connective tissue around the first rib was dissected. The axillary approach may be less risky for arterial damage.

The periosteum of ribs in healthy calves can be exfoliated from the bones, and partial costectomy can be performed without incision of the pleura and exposing the thoracic cavity [6]. However, the periosteum adheres with bones or callus in calves with rib fractures, and the ribs must be resected with the pleura. Although the calves fell into the condition of thoracotomy immediately following the costectomy, there were no complications from routine anesthesia techniques.

The prognosis in previous reports has been unfavorable in the involved calves with surgical treatments, and the growth of the calves relatively retarded [4, 5, 12, 17]. Cases 1 and 3 had no sign of trouble from their conditions post-surgery through auction time at their farms. On the contrary, Case 2 returned to the preoperative condition three months post-surgery and showed growth retarding. Preoperative conditions including the severity of rib fractures and respiratory signs, and the durations of the disease, may influence postoperative performances of involved calves treated with partial costectomy. In such case, re-evaluation of the tracheal condition and rib fractures by radiography and CT and additional costectomy and/or tracheal expansion with utilization of prosthesis should be considered. The prosthesis would be suitable to make of flexible and substantial materials to adapt the tracheal size of growing calves, because previous reports describe recurrence of respiratory distress caused by luminal narrowing of trachea in calves treated with using extra-tracheal prosthesis of polypropylene plastic syringe [4, 12].

At present, authors consider that partial costectomy may be an effective treatment for calves with wheezing associated with tracheal collapse and stenosis due to perinatal rib fractures, except for severe cases. Additional cases with various severities of the disorder would be required to discuss the surgical criteria and determine how best to achieve a favorable prognosis for the calves.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahern B. J., Levine D. G.2009. Multiple rib fracture repair in a neonatal holstein calf. Vet. Surg. 38: 787–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2009.00567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashworth C. D., Walling M. A., Mirsky M. L., Smith R. M.1992. Tracheal collapse in a holstein heifer. Can. Vet. J. 33: 50–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busschers E., Epstein K. L., Holt D. E., Parente E. J.2010. Extraluminal, C shaped polyethylene prosthesis in two ponies with tracheal collapse. Vet. Surg. 39: 776–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2010.00715.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fingland R. B., Rings D. M., Vestweber J. G.1990. The Etiology and surgical management of tracheal collapse in calves. Vet. Surg. 19: 371–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.1990.tb01211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaughan E. M., Provo-Klimek J., Ducharme N. G.2004. Surgery of the bovine respiratory and cardiovascular systems. pp.141–159. In: Farm Animal Surgery (Fubini, S. L. and Ducharme, N. G. eds.), Saunders, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendrickson D. A.2007. Miscellaneous bovine surgical techniques. pp.273–288. In: Techniques in Large Animal Surgery, 3rd ed. (Henderickson, D. A. ed.), Blackwell Publishing, Ames. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horney F. D.1975. Tracheal prosthesis in a calf. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 167: 463–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwamoto J., Yamagishi N., Sasaki K., Kim D., Devkota B., Furuhama K.2012. A novel technique of ultrasound-guided brachial plexus block in calves. Res. Vet. Sci. 93: 1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2012.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jelinski M., Vanderkop M.1990. Tracheal collapse/stenosis in calves. Can. Vet. J. 31: 780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacPhail C. M.2013. Surgery of the upper respiratory system. pp.906–957. In: Small Animal Surgery, 4th ed. (Fossum, T. W. ed.), Elsevier, St.Loius. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogasawara T., Kawara S., Hoshi F., Yamazaki N., Fukumura T., Ogasawara S.1991. Tracheal collapse in three calves; surgical approach and pathological observation. Tohoku J. Vet. Clin. 14: 1–6(in Japanese with English summary). doi: 10.4190/jjvc1990.14.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rings D. M.1995. Tracheal collapse. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 11: 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robertson J. T., Spurlock G. H.1986. Tracheal reconstruction in a foal. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 189: 313–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuijt G.1990. Iatrogenic fractures of ribs and vertebrae during delivery in perinatally dying calves: 235 cases (1978–1988). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 197: 1196–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vestweber J. G., Leipold H. W.1984. Tracheal collapse in three calves. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 184: 735–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watt B. R.1983. Collapse of the trachea in two calves. Aust. Vet. J. 60: 309–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1983.tb02818.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woolums A. R., Baker J. C., Smith J. A.2009. Diseases of the pharynx, larynx, and trachea. pp.595–601. In: Large Animal Internal Medicine, 4th ed. (Smith, B.P. ed.), Mosby, St. Louis. [Google Scholar]