Abstract

Many foster youth experience maltreatment in their family-of-origin and additional maltreatment while in foster care. Not surprisingly, rates of depression are higher in foster youth than the general population, and peak during ages 17 to 19 during the stressful transition into adulthood. However, no known studies have reported on whether foster youth perceive positive changes following such adversity, and whether positive change facilitates psychological adjustment over time. The current study examined components of positive change (i.e., compassion for others and self-efficacy) with depression severity from age 17 to 18 as youth prepared to exit foster care. Participants were youth from the Mental Health Service Use of Youth Leaving Foster Care study who endorsed child maltreatment. Components of positive change and severity of abuse were measured initially. Depression was measured initially and every three months over the following year. Latent growth curve modeling was used to examine the course of depression as a function of initial levels of positive change and severity of abuse. Results revealed that decreases in depression followed an inverse quadratic function in which the steepest declines occurred in the first three months and leveled off after that. Severity of abuse was positively correlated with higher initial levels of depression and negatively correlated with decreases in depression. Greater self-efficacy was negatively associated with initial levels of depression and predicted decreases in depression over the year, whereas compassion for others was neither associated with initial depression nor changes in depression. Implications for intervention, theory, and research are discussed.

Keywords: foster youth, child maltreatment, perceived benefits, posttraumatic growth, depression, growth model

Foster care is a service within the child welfare system, a federally funded system that provides services to vulnerable children. Foster care intervenes and places youth in a “substitute home” when biological or primary caregivers are not able to provide adequate care for their children. Foster care is responsible for ensuring safety, stability, and well-being. In 2010, 408,425 children and adolescents in the United States were in the foster care system (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [U.S. DHHS], 2011), and many of these youth had spent a substantial amount of their childhood in foster care. The 254,114 youth who exited the foster care system in 2010 had been in care for an average of 22 months, and more than a quarter had been in care for more than two years (U.S. DHHS, 2011). The majority of children who entered foster care for the first time in the last six months of 2009 were still in foster care 12 months later, while those who were reunified with their families had a high likelihood of reentering foster care in less than 12 months (U.S. DHHS, 2011). Additionally, stability within foster care is rare; in 2010, 67% of children who were in foster care for 24 months or longer had been placed with more than two foster families (U.S. DHHS, 2011).

The transition from family-of-origin or primary caregivers to foster care, and between foster families within the foster care system, can be highly stressful. Unfortunately, these stressful and potentially traumatic experiences are often preceded by exposures to other trauma and maltreatment necessitating foster care. According to the Casey National Alumni Study, over 90% of adults formerly in foster care had experienced at least one form of childhood maltreatment; the most common types of maltreatment that were alleged or confirmed were sexual abuse combined with another form of maltreatment (40.8%), combined physical abuse and neglect (16.6%), and physical neglect with or without emotional abuse (14.6%; Pecora et al., 2003). Unfortunately, abuse does not always cease once youth enter the foster care system, as many continue to experience maltreatment while in foster homes by their foster parent(s) (Courtney, Piliavin, Grogan-Kaylor, & Nesmith, 2001). One study reported that 40% of foster care youth endorsed some type of maltreatment while in foster care (Salazar, Keller, & Courtney, 2011). Yet, services that address the unique ongoing mental healthcare needs of foster care youth are not systematically required, and only a fraction of foster care youth who evidence clinically significant psychiatric symptoms receive mental health care (Burns et al., 2004).

Thus, youth transitioning out of the child welfare system typically have trauma histories and mental health needs that have not been addressed, which poses a variety of challenges as these youth begin their adult lives. In fact, one study found that the strongest predictor of psychiatric problems in youth exiting the foster care system was the sum of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect (McMillen et al., 2005). In the face of difficult histories and ongoing mental health challenges, youth in transition from foster care to adulthood are a particularly vulnerable population, given their abrupt transition from dependency to the responsibility of self-sufficiency. Many foster youth lack critical foundations of emotional, social, and financial support that are typical of young people in the midst of transitioning into adulthood. Thus, foster youth are in particular jeopardy of experiencing negative outcomes and face considerable challenges to secure resources and opportunities needed face key developmental tasks that lead to stable and productive lives. Studies have shown that after entering into independent living, many foster youth alumni fair relatively poor in terms of education, unstable employment and economic well-being, early pregnancy, family formation, crime and incarceration, and mental health (Courtney & Dworsky, 2006; Reilly, 2003). It has been observed that foster youth have higher rates of depression than the general population, at a rate of two (Havalchak et al., 2007) to three (McMillen et al., 2005) times those observed in the general population. In the Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth, the lifetime prevalence rate of depression for these foster youth increased from 2.9% to 8.3% from age 17 to 19 (Courtney et al., 2005; Courtney, Terao, & Bost, 2004), suggesting that foster youth may be psychologically unprepared for the transition to adulthood and independent living, and thus, experience an exacerbated risk for developing depression during this transitional period. In this sample, both pre-care and during-care maltreatment were associated with depressive symptoms (Salazar, 2011).

More recently, however, researchers have also identified that such adversity can be associated with positive change or what has been referred to as posttraumatic growth, benefit finding, thriving, and stress related growth. These concepts have been collectively described as “the positive effects that result from a traumatic event” (Helgeson, Reynolds, & Tomich, 2006, p. 797), and what will be referred to as “positive change” through the remainder of this paper. Despite differences in terminology, the various instruments to assess positive change have been shown to load on a single component, and therefore, researchers have suggested that “various measures of positive change all appear to be assessing the same broad construct, a finding that should facilitate the integration of different theoretical and empirical traditions in the study of positive change following trauma and adversity” (Joseph, Linley, & Harris, 2006, p. 94). Positive change is the experience of a reconfiguration of one’s goals, beliefs, and worldview as a result of one’s struggle with trauma (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995). That is, traumatic events challenge one’s pre-trauma schema regarding themselves, others, their relationships, and the world. Over the course of successful coping and schematic reconstruction, life takes on new value and one considers what is important, reprioritizes, and makes positive changes about how to live. Perceived positive changes attributed to this process tend to cohere in several main domains, including changed self-perceptions, a different perspective on one’s relationships, and a changed philosophy of life (Joseph et al., 2006).

Although positive change has its roots in ancient literature and has been promoted in popular phrases such as “That which does not kill me makes me stronger” (Nietzsche, 1889/1990), only recently have researchers begun to empirically investigate the concept of positive change. This field of research has the potential to illuminate pathways to positive adjustment and mechanisms of effective intervention following adversity. However, the study of positive change has, for the most part, been focused on adults and no known research has investigated this concept in foster care youth. Additionally, the positive change literature has been fraught with inconsistent findings regarding the link between perceived positive change and mental health; studies have found that positive change is positively, inversely, and unrelated to mental health (Park & Helgeson, 2006). In some cases, positive change is curvilinearly associated with mental health, specifically when assessing posttraumatic stress symptoms (Shakespeare-Finch & Lurie-Beck, 2014).

With the proliferation of positive change research in the last decade, systematic review has been possible and has provided a better understanding of the relation between positive change and mental health. With regard to depression, one meta-analytic review found that depression was generally not associated with positive change, though the two significant relations found (i.e., Frazier, Conlon, & Glaser, 2001; Updegraff, Taylor, Kemeny, & Wyatt, 2002) were in the expected direction; more positive change was associated with less depression (Linley & Joseph, 2004). In another meta-analytic review, utilizing 17 studies representing 6,396 individuals, positive change was related to less depression (Helgeson et al., 2006). This was represented by an effect size of −.09. Additionally, positive change was more strongly related to less depression when the time since the traumatic event was more than two years, suggesting that positive change may take time to occur (Helgeson et al., 2006).

Only recently has there been sufficient research on positive change to justify a review among children and adolescents, which mirrors the adult literature, in finding inconsistent associations between positive change and depression (Meyerson, Grant, Carter, & Kilmer, 2011). That is, positive change has been found to be negatively related (Vaughn, Roesch, & Aldridge, 2009) and unrelated (Milam, Ritt-Olson, & Unger, 2004) to depressive symptoms. Of interest, one longitudinal study found that those who reported greater positive change at initial assessment exhibited less emotional distress up to 12 and 18 months later (Ickovics et al., 2006). This is consistent with findings from an adult sample that found positive change following sexual assault was associated with less depression over a year (Frazier et al., 2001). Taken together, these studies suggest that longitudinal research may illuminate patterns of mental health outcomes as they relate to positive change following adversity.

Theorists have suggested that inconsistent findings between positive change and mental health symptoms may be related to the time that has transpired since the trauma occurred (Helgeson et al., 2006). For example, positive change may be associated with poor mental health outcomes when assessed soon after the trauma but better mental health outcomes when assessed after more time has elapsed since the trauma. It has also been suggested that positive change and mental health assessed together soon after the event may reflect a cognitive strategy used to reduce distress (Helgeson et al., 2006). Much of the positive change research to date has been limited by an over-reliance on cross-sectional studies, which may partly account for inconsistent findings. Positive change is conceptualized as a process that unfolds over a series of phases in which some level of distress is seemingly necessary to catalyze the personal growth process, but too much may impede the possibility of positive change (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995).

Furthermore, research has suggested that inconsistent findings may be related to the fact that positive change is multidimensional in nature. Most research examining positive change as it relates to mental health outcomes collapses subscales on positive change measures into one dimension, when in fact, empirical research has demonstrated that items on positive change measures load onto three main factors: changed self-perceptions, a different perspective on one’s relationships, and a changed philosophy of life (Joseph et al., 2006). Different areas of positive change are potentially affected by different variables and have varying relations with mental health outcomes following adversity. For example, in one study “changed self-perceptions” were negatively correlated with PTSD symptoms whereas “a different perspective on one’s relationships” was positively but non-significantly related to PTSD symptoms (Powell et al., 2003). Thus, it is important for positive change research to examine both the longitudinal course of mental health symptoms as they relate to positive change, as well as how different components of positive change predict mental health symptoms over time.

The purpose of this study is to examine potential components of positive change that predict depression as youth prepare to exit foster care. A better understanding of who benefits from adverse events and why can inform intervention efforts so as to strengthen those factors that increase successful outcomes or help individuals explore avenues that may promote positive change. To this end, secondary data analysis was conducted on the Mental Health Service Use of Youth Leaving Foster Care (Voyages) 2001–2003 study (McMillen, 2010), utilizing two components of positive change from the Perceived Benefits Scale (PBS; McMillen & Fisher, 1998), that of “increased compassion for others” and “enhanced self-efficacy.” Compassion for others and self-efficacy load on domains that assess positive changes in one’s relationships and in self-perceptions, respectively (Joseph et al., 2006).

Compassion for others and enhanced self-efficacy appear to be the most robust predictors of positive change and mental health, respectively. The compassion for others PBS subscale is unique among measures of positive change as it is the only subscale that assesses this component. In the development of the PBS, it was the most highly endorsed positive change (McMillen & Fisher, 1998). With regard to its relation to depression, increased compassion for others was positively associated with depressive symptoms, suggesting that individuals who continue to suffer may find themselves more compassionate to others (McMillen & Fisher, 1998). In contrast, a related study found that compassion for others interacted with social support to buffer one’s physiological reactivity to stress, suggesting that compassion for others may increase our ability to receive social support and lead to more adaptive reactions to stress (Cosley, McCov, Saslow, & Epel, 2010). Longitudinal research would be needed to further inform whether compassion for others is an important factor in the maintenance or recovery of depressive symptoms.

Enhanced self-efficacy has been shown in numerous meta-analyses to be a robust contributor to the quality of human functioning, and recent research has verified its independent contribution to posttraumatic recovery across a wide range of traumas, suggesting that self-efficacy is central to the enabling and protective function of the belief that one is capable of exercising control over traumatic adversity (Benight & Bandura, 2004). With regard to enhanced self-efficacy in foster care youth, studies have found that a self-reported higher level of preparation for leaving foster care resulted in the largest reduction in the estimated probability of retrospective depression (e.g., White, 2009). Thus, youth who perceive enhanced self-efficacy as a result of struggling with adversity may feel more confident in their ability to manage additional stressors, which may buffer against the feelings of helplessness and depressive reactions as youth near their exit from foster care. In the development of the PBS, self-efficacy was unrelated to depressive symptoms (McMillen & Fisher, 1998), though this again raises the issue of cross-sectional research when examining positive change.

Given that the mean age of entry into the foster care system for this sample of youth was 10.6 and that the mean age of onset for major depression in this sample was 11.82 (McMillen et al., 2005), we may surmise that the majority of adversity was experienced and subsequent depression was triggered before their teenage years. Thus, these youth had several years to process their childhood trauma histories and experience the process of positive change by their 17th birthday, while potentially coping with ongoing trauma and depression. Therefore, we aim to examine the relation between initial levels of enhanced self-efficacy and increased compassion for others when the youth were of age 17 (a year before their exit foster care), with depression severity over the course of the year as they approached age 18 (preceding the potentially difficult life transition out of foster care). It was of interest to examine how positive change at age 17 predicts psychological adjustment or maladjustment during an especially difficult and/or stressful life experience to better understand how positive change relates to mental health processes. Examining depression over a one year time period, from age 17 to age 18, seemed reasonable and appropriate given that previous longitudinal research with both adolescents and adults found that initial levels of positive change predict less emotional distress and depression after a year (i.e., Frazier et al., 2001; Ickovics et al., 2006).

Informed by this previous research, it was hypothesized that youth will experience increased depressive symptoms over the course of the year preceding exit from foster care, as they are confronted with the realization that their resources are not adequate to meet life’s demands. Additionally, it was hypothesized that both severity of abuse history and increased compassion for others will be positively associated with initial levels of depression, whereas enhanced self-efficacy will be negatively associated with initial levels of depression. Lastly, it was hypothesized that severity of abuse history will be associated with increased depression over the course of a year, whereas enhanced self-efficacy will be associated with decreased depression over the year. Given that compassion for others is an understudied variable in the field of positive change, no predictions were made as to the relation between compassion for others and depression over time.

Method

Participants

The full sample of participants consisted of 406 youth initially aged around 17 years old (M=16.99, ranging from 16.9 to 17.5) who were in foster care and residing in one of eight selected counties in Missouri. The sample consisted of 228 females (57%) and 178 males (43%). The sample included 178 Caucasian youth (44%), 204 were African American (50%), 14 were of mixed race (3.4%), 3 were American Indian (0.7%), 4 were Latino (1%), and 2 were of other race (0.5%). Only those with a self-reported abuse history (physical, emotional, and/or sexual) on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein & Fink, 1998) were included in the analyses, as these served as indicators of childhood maltreatment. This resulted in a subsample of 373 youth. The average age was 16.35 (SD = 0.78). The majority were female (n = 205, 55%). Most were African American (50.1%) or Caucasian (44.8%).

Procedure

The original study was funded to explore changes in mental health service use as youth leave the foster care system, but the study examined many parameters of the lives of foster care youth. The study was a longitudinal cohort design. Participants were interviewed every three months from age 17 to 19 (nine interviews total). Data collection began December 2001 and ended June 2003. Few variables were assessed at every interview.

Participants were recruited through the Missouri Children’s Division (MCD), the child welfare authority in Missouri. Each month from December 2001 to May 2003 the MCD provided the research team the names and caseworkers of youth who were turning 16.9 years of age and were in the custody and care of the MCD. The MCD foster care case manager was then contacted to provide informed consent. After the case manager consented, youth were contacted and invited to participate. A total of 647 youth were referred to the project, but only 451 were determined to be eligible to participate. Only those participants who were able to speak and understand English, had an IQ above 70, and who were not on “runaway status” for more than 45 days were included. Of the 451 youth determined to be eligible to participate, 407 (90%) were interviewed at the initial assessment. Not all participants completed all waves. Attained retention was 80% (325 participants completed the final interview).

The first and last interviews were in-person and the data were collected via multiple measures combined together into one survey that was administered in person. Data collection from time 2 to time 8 was completed via telephone interviews. Youths were paid $40 for the initial and final interviews, and $20 for interviews two through eight. The interviews were conducted by trained professional interviewers at the youths’ homes or the facilities in which they were living. The predictor variables (i.e., compassion for others and self-efficacy) for this study were only assessed at the first time point. Depression was measured across all nine time points. For the purpose of this study, data from the initial interview and depression scores over the last year in foster care (i.e., five time points) were used for the analyses. Thus, a five-time point longitudinal design in which the spacing of assessments at 3-month intervals was the same for all individuals was utilized.

Measures

Childhood Trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein & Fink, 1998) is a self-report measure that assesses retrospective accounts of child maltreatment. There are a total of 25 items that can be divided into subscales that assess sexual abuse, physical abuse, physical neglect, emotional abuse, and emotional neglect. The items are rated with the following response options: never true, rarely true, sometimes true, often true, and very often. The CTQ also includes an additional minimization/denial subscale to detect false-negative abuse reports. In the original study, only physical abuse, emotional abuse, and physical neglect were assessed. Additionally, in the original study, the researchers created and included 3 items with dichotomous response options to assess sexual abuse history. For the purpose of this study, only those who endorsed a history of childhood maltreatment in the forms of physical abuse, emotional abuse, and/or sexual abuse were included. Scores on the physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse subscales were summed to create a total continuous score of childhood maltreatment. The CTQ has demonstrated its validity and reliability (α ranging from .74 to .94), test-retest reliability (intraclass correlation = .88), as well as convergence with concurrent interviews on childhood trauma among clinical and non-clinical populations (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997; Bernstein & Fink, 1998). Internal consistency in the present study was: physical abuse (α = .87), emotional abuse (α = .86), sexual abuse (α = .84), and childhood maltreatment (α = .90).

Positive Changes

Perceived positive life changes resulting from adverse experiences were assessed with the Perceived Benefits Scales (PBS; McMillen & Fisher, 1998). The PBS is a 30-item scale that assesses commonly reported positive changes following adversity across eight factors: enhanced self-efficacy, increased faith in people, increased compassion for others, increased spirituality, increased community closeness, enhanced family closeness, lifestyle changes, and material gain. In this study, four items from the enhanced self-efficacy subscale (e.g., “My difficult experiences taught me I can handle anything”) and four items from the increased compassion for others subscale (e.g., “As a result of my difficult experiences, I am more sensitive to the needs of others”) were administered to examine how participants might have been changed as a result of adversity. Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all like my experiences) to 4 (very much like my experiences), with higher mean scores indicating greater perceived positive benefits following adversity. Items on the PBS were empirically generated from lists of statements based on general reflection from adverse events that trauma survivors had experienced. This is a different approach from item development of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996) in which item generation was guided by theory. Although the PBS and the PTGI were created using different approaches to item development, both scales tap changes in self-perception (i.e., enhanced self-efficacy); however, the PBS adds incremental content validity by assessing empathy for the suffering of others with a whole subscale (i.e., increased compassion for others), which is only assessed by one item of the PTGI. In fact, increased compassion for others was not associated with any of the subscales on the PTGI (McMillen & Fisher, 1998), suggesting that this PBS subscale provides a unique contribution to the assessment of positive changes in interpersonal relationships. In the original development sample, Cronbach’s alphas were reported to be .88 for the enhanced self-efficacy subscale and .87 for the increased compassion subscale, and convergent validity of PBS subscales were demonstrated by high correlations with subscales from an inventory of posttraumatic growth. Internal consistency in this sample was .75 and .81 for the enhanced self-efficacy and increased compassion subscales, respectively.

Depression

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Depression-Arkansas Scale (D-ARK; Smith et al., 2002; Walter, Meresman, Kramer, & Evans, 2003) of the Depression Outcomes Module (DOM, Smith, Burnam, Burns, Cleary, & Rost, 1994). The D-ARK is an 11-item measure used to assess the experience of depressive symptoms in the past four weeks (e.g., “How often in the past 4 weeks did you have days in which you experienced little or no pleasure in most of your activities?”). Response options range from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (Nearly every day for at least 2 weeks). However, item analyses revealed that the two items that assess suicidal ideation and intent were endorsed at a low base rate in the present sample, and therefore, do not represent reliable indicators of the construct in this sample. These two items were deleted from the model, which significantly improved model fit. Following the directions of Smith et al. (2002), raw scores on the D-ARK are transformed to scores scaled from 0 to 100 with scores 30 or greater reflecting clinically significant depression. The D-ARK has been tested in culturally diverse populations and has evidenced adequate internal consistency (ranging from .81 to .86) and convergent validity, with depression severity on the D-ARK being correlated with depression ratings on Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), as well as a similar factor structure to the BDI-II (Walter et al., 2003). Internal consistency of the D-ARK in this sample was .84 at the initial interview.

Analytic Strategy

The analytic strategy adopted in this study was modeled on the integrative approach proposed by Chan (1998) called the LMACS-MLGM methodology. This approach incorporates two powerful and flexible longitudinal change assessment methods, namely, longitudinal mean and covariance structures analysis (LMACS) and multiple indicator latent growth modeling (MLGM). Using this approach, the first step (LMACS) involves specifying a confirmatory measurement model and then establishing measurement invariance of construct indicators across time. With this approach we can ensure that the measurement properties of the multiple measures of depression obtained at five periods were equivalent and, thereby provide evidence that any construct mean differences obtained in MLGM analyses are meaningful. In the second step (MLGM), the longitudinal measurement model serves as a basis for estimating both the form of change over time and then the factors that influence these changes. Specifically, we examined the growth trajectories of youth depression from age 17 to 18 and then assessed whether these changes were a function of inter-individual differences in severity of abuse, self-efficacy and compassion for others.

The analyses were conducted with item covariance matrices in LISREL 9.1 using maximum likelihood estimation. Specification of models at each step of the LMACS-MLGM approach is described below. As is common practice (Kline, 2011), model fits were evaluated using a variety of fit indices. Assessment of overall model fit was based on both absolute and incremental fit indices. Absolute indices include the χ2 likelihood ratio test and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Cudeck & Browne, 1983). Because the χ2 test is extremely sensitive to sample size, this fit index should be interpreted with caution. The RMSEA calculates the ratio of the minimum fit function per degree of freedom, which provides a measure of discrepancy between the elements in the sample and the hypothesized covariance matrix. According to Little (2103), an RMSEA of .05 indicates a good fit whereas values below .08 indicate an acceptable model fit (see also Brown, 1982). LISREL also produces a 90% confidence interval that can be used to compare alternative models. Other fit indices that are also less influenced by sample size were employed to assess goodness of fit. The normed fit index (NFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) both indicate the improvement of the overall fit of the hypothesized model relative to a null model. The CFI is a modified version of the NFI based on the non-central χ2. An acceptable fitting model is indicated by NFI, TLI, and CFI values greater than .90 (Kline, 2011).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Mean scores on the childhood physical abuse and childhood emotional abuse subscales of the CTQ were 11.59 (SD = 5.99) and 13.25 (SD = 6.06), respectively, indicating that, on average, participants experienced physical and emotional abuse “sometimes” to “often” during childhood. Many participants experienced some form of sexual abuse (37.5%); 22.8% reported being forced to fondle another person (n = 85), 35.1% reported being fondled against their will (n = 131), and 22% reported being forced to have sex (vaginal, oral, or anal) against their will (n = 82). Fifty-six participants (15%) endorsed all three sexual abuse items.

With respect to aspects of positive change, mean scores on enhanced self-efficacy and increased compassion for others were 11.55 (SD = 3.36) and 11.57 (SD = 3.74), respectively. Thus, on average, participants reported experiencing “much” positive change as a result of adversity. These scores are similar to the development sample of community adults in which those who experienced a traumatic event reported a mean of 12.14 and 11.19 on self-efficacy and compassion for others, respectively (McMillen & Fisher, 1998).

The percentage of those who reported clinically significant depressive symptoms at the initial interview and at age 18 were 18% and 10.5%, respectively. The initial rate of depression is in the range of the rates of clinically significant depression (19% in females, 16% in males) as assessed with the D-ARK in a primary care sample under the age of 65 (Walter et al., 2003). Mean scores on depression outcomes ranged from 17.98 (SD = 17.35) at Time 1 to 11.52 (SD = 13.40) at Time 5, indicating that depression severity significantly decreased (ΔM = 6.47) over the course of the year youth were preparing to exit the foster care system, t(371) = 7.28, p < .001.

Confirmatory Measurement Model

Based on prior research and theory bearing on the constructs of interest, an eight factor measurement model was specified as follows: severity of abuse (three indicators), initial self-efficacy (four indicators), initial compassion for others (four indicators), and depression measured at five time points (nine indicators at each point). In addition, item measurement errors were presumed to be uncorrelated and the latent variables were permitted to intercorrelate. Examination of fit indices for the proposed eight-factor model revealed an acceptable level of fit (χ2(df = 1456) = 2736.47, p < .001; RMSEA = .0486; NFI = .865; TLI = .928; CFI = .932). All factor loadings relating each item to its intended construct were significant. Having demonstrated an acceptable factor structure, we could then turn our attention to 1) demonstrating measurement invariance of the depression measures over time, 2) modeling the form of change in mean levels of depression, and 3) relating mean level changes in depression to the initial factors of severity of abuse, self-efficacy, and other compassion.

Measurement Invariance of Depression over Time

Prior to examining changes in mean levels of depression across time, it was important to demonstrate that the measurement properties of the depression scales were consistent across the five time points. This process began by focusing on solely the measures of depression, with the specification of an unconstrained measurement model (Model 1) that served as a baseline for subsequent nested model comparisons. In this model, as recommended by Little (2013), the residuals of individual depression items that were repeated across the five time points were allowed to covary. As expected based on the measurement model described above, the unconstrained model fit the data well (see Table 1). The RMSEA was below .05 and the other fit indices we above .90. Next we estimated a model in which the item factor loadings were constrained to be equal across each of the five time points (Model 2). Fit indices for this weak invariance model indicated an acceptable overall fit and although comparing this model to the unconstrained model produced a significant difference in χ2, there were negligible differences in the other fit indices (RMSEA, NFI, TLI, and CFI). Next we estimated a strong invariance model with equivalent factor loadings and indicator intercepts across the five time periods (model 3). The overall fit of model 3 was acceptable and, as before, there were only minor differences in the RMSEA, TLI, and CFI when compared with model 2. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the measurement properties of depression remained constant across the five time points and, therefore, the construct means could be meaningfully compared. Note that all subsequent model specifications retain the equality constraints (in both factor loadings and indicator intercepts) tested above.

Table 1.

Results of LMACS Analyses Demonstrating Measurement Invariance of Depression Measures over Time (N = 373)

| Model | χ2 | df | Model Comparison |

Δχ2(df) |

RMSEA (CI) | NFI | TLI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1Baseline (no constraints) |

1605.58** | 845 | -- | .0491 (.046, .053) |

0.903 | 0.943 | 0.951 | |

| M2 Weak Invariance (equal factor loadings) |

1711.33** | 877 | M1 vs. M2 | 105.8 (32)** | .0505 (.047, .054) |

0.897 | 0.940 | 0.947 |

| M3 Strong Invariance (equal factor loadings and item intercepts) |

1776.44** | 909 | M2 vs. M3 | 65.11 (32)* | .0506 (.047, .054) |

0.893 | 0.939 | 0.944 |

p < .01,

p < .001

Note: df= degree of freedom; RMSEA= root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval; NFI = normed fit index; TLI = non-normed fit index; CFI = comparative fit index. For descriptions of model specifications, see text.

Modeling Change in Means of Depression over Time

Next, we consider the changes in mean levels of depression over time. In the strong invariance model described above, the means of the latent constructs were scaled such that the initial level of depression represents a baseline and the means at subsequent time points can be interpreted as differences from that initial level. One advantage of this approach is that the significance test of the subsequent means represents a test of the difference between the initial level of depression and that time point. Relative to the initial level of depression, mean levels of depression decreased over the last four time points for the entire sample and were −.168, −.240, −.242, and −.262. Each of these values are significantly different from zero (i.e., the initial time point) with all p values < .001. The values indicate that the largest decrease in depression severity is between Time 1 and Time 2, after which decreases in depression severity begin to level off and approaches an asymptote from Time 2 to Time 5. Thus, contrary to the first hypothesis, depression scores decreased over the course of the year preceding youths? exit from foster care.

The strong invariance model also represents a baseline from which models representing the change in means can be compared. Table 2 presents the results of latent growth models used to model changes in depression. The first model to be fit to the data was an unconstrained “shape” model, which included two latent factors to model the changes in mean levels of depression over the five time points. This model included an intercept factor and a shape factor as depicted in the lower portion of Figure 1. In this model the intercept factor is scaled such that its mean represents the mean level of depression at time 1. The loadings of the shape factor are specified such that the change between time 1 and time 2 provides the scale for estimates of changes occurring at times 3–5. As shown in Table 2, the unconstrained shape model provided a good fit to the data as judged by the values of the RMSEA, TLI, and CFI and was not significantly different than baseline model. In addition, consistent with the results just described in the paragraph above, the mean of the shape factor was significant (−.1771, p < .001), indicating that there are reliable decreases in mean levels of depression. Estimates of the free loadings in the shape model, relating the shape factor to means at times 3–5, were 1.33, 1.45 and 1.36 (all significant at p < .001) and indicate that levels of depression decreased from the initial levels and leveled off at an asymptote. These estimates suggest that changes in depression could be modeled with a combination of linear and quadratic functions.

Table 2.

Results of MLGM Analyses Describing Changes in Depression over Time (N = 373)

| Model | χ2 | df | Δχ2 | Δ df | p | RMSEA (90% CI) |

NFI | TLI | CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strong Invariance Model |

1776.44** | 909 | --- | --- | --- | 0506 (.047, .054) |

0.893 | 0.939 | 0.944 |

| Unconstrained Shape |

1782.69** | 916 | 6.25 | 7 | ns | .0504 (.047, .054) |

0.892 | 0.940 | 0.944 |

| Linear Change | 1810.94** | 919 | 34.5 | 10 | <.01 | .0510 (.048, .054) |

0.890 | 0.938 | 0.943 |

| Inverse Quadratic Change |

1779.11** | 915 | 2.67 | 6 | ns | .0503 (.047, .054) |

0.893 | 0.940 | 0.945 |

Note: df= degree of freedom; RMSEA= root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval; NFI = normed fit index; TLI = non-normed fit index; CFI = comparative fit index. For a description of the models, see text.

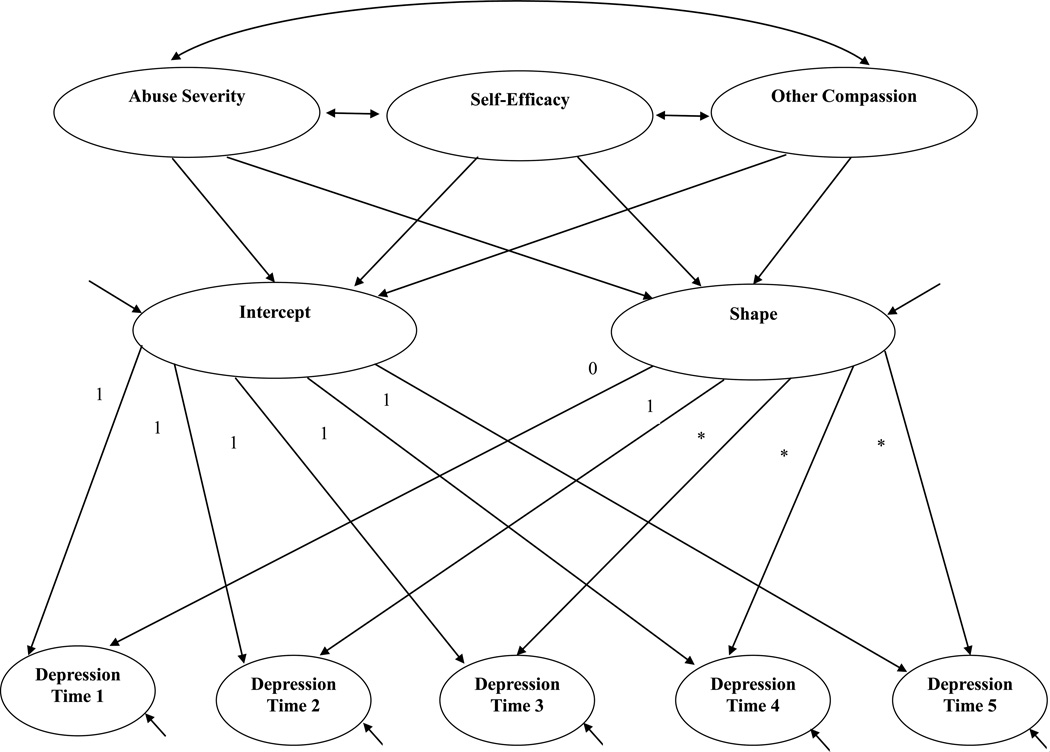

Figure 1.

Depression severity predicted by severity of abuse, enhanced self-efficacy, and increased compassion for others.

To determine the specific nature of changes in depression, two additional models were estimated. The first replaced the unspecified shape factor with a linear change factor by specifying a fixed set of factor loadings (i.e., 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) for a linear trajectory. The second model also included an inverse quadratic change factor with loadings fixed to specify a curvilinear trajectory that approaches an asymptote (i.e., 0, 1, 1.41, 1.73, 2). These coefficients are produced by taking the square root of the linear coefficients. Taken together, these factors can model a trajectory of changes in means that show an overall decline and slowing of that decline over time. As seen in Table 2, both of these models fit the data reasonably well; however, the model that includes both linear and inverse quadratic change functions is preferred. In this model both the linear and inverse quadratic factors were significant (p’s < .01). In addition, in this model, there was significant variance in the intercept, linear change, and inverse quadratic change factors, indicating that individual differences may predict changes in depression over time.

Individual Predictors of Changes in Depression over Time

To examine the associations between individual predictors and changes in depression severity, severity of abuse and the two positive change predictor variables (i.e., enhanced self-efficacy and increased compassion for others) were included as predictors of the initial level and change factors previous model. As hypothesized, severity of abuse was associated with higher initial levels of depression (γ = 0.042, p < .001). In addition, self-efficacy was also related to initial levels of depression, such that enhanced self-efficacy was associated with less depression (γ = −.236, p < .001). Contrary to our hypothesis, however, compassion for others was not related to initial levels of depression. In looking at the effects of the individual predictors on the change factors, only severity of abuse and self-efficacy showed significant effects on only the inverse quadratic function. Greater severity of abuse predicts a faster slowing of the decrease in depression such that individuals reporting higher levels of abuse plateau at a higher level of depression than those reporting less severe abuse. Conversely, individuals scoring higher on the self-efficacy plateau at a lower level of depression than those reporting lower self-efficacy.

Discussion

Unstable living conditions and trauma exposure, both of which prevail among foster youth, render elevated risk for various mental health difficulties such as depressive disorders (McMillen et al., 2005). In addition to common reasons for foster care placement (e.g., parental substance abuse, parental mental or developmental disabilities, and home impoverishment), the majority of foster children witnessed or directly experienced violence in their family of origin (e.g., Pecora et al., 2003). Unfortunately, many of them continue to experience maltreatment in foster care (Courtney et al., 2001; Salazar et al., 2011). The present sample also reported an extensive history of maltreatment. The majority of foster youth endorsed a history of regular physical and emotional abuse; more than one third of the sample had experienced some form of sexual abuse.

In spite of these onerous life experiences, burgeoning research on positive change claims that undergoing significant life adversity may contribute to the development of positive life growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004, p.1). In the present study, we investigated potential components of positive change (as measured by self-efficacy and other compassion) that predict depression over time as youth prepare to exit foster care. Our first hypothesis – youth will experience increased depressive symptoms over the course of the year preceding exit from foster care, as youth are confronted with the realization that their resources are not adequate to meet life’s demands – was not supported. Rather, depressive symptom severity over time was best described with a non-linear decreasing trajectory. Foster youth displayed a significant reduction in depressive symptoms over time, especially between Time 1 (initial interview) and Time 2 (three months after the initial interview). Further, depressive symptom severity reached an asymptote after Time 2, suggesting that the majority of youth experienced minimal depressive symptoms after their second interview as they approached exit from foster care.

It is surprising that the majority of the present sample was relatively well-adjusted in regard to mental health. It is possible that youth became better adjusted after leaving an unsafe living environment and are no longer dependent on potentially abusive caregiver(s). Alternatively, we may also interpret this finding as outcomes of successful mental health, mentoring, or training programs in helping prevent negative outcomes among foster youth, as the majority of the sample had utilized mental health programs (McMillen, Scott, Zima, Ollie, Munson, & Spitznagel, 2004). Many of the youths also identified a supportive nonkin mentor whom they met through formal systems of care such as child welfare, school, and mental health agencies (Munson & McMillen, 2008). Therefore, these programs may enhance perceived self-efficacy, engagement in coping strategies, and connection to resources via transitional programming. Sufficient preparation is especially vital as foster youth are preparing to exit foster care. One study found that many youth benefited from mentoring programs that assisted them in acquiring skills and resources necessary for this transition (Osterling & Hines, 2006). An adequate amount of preparation for leaving foster care can also reduce subsequent risk of depressive symptoms (White, 2009).

Over the course of the year preceding foster care exit, foster youth differed in their reduction rate of depressive symptoms. We examined whether this differential rate of decrease was related to individual differences in severity of abuse, self-efficacy, and compassion for others. As hypothesized, youth who reported more severe abuse endorsed higher levels of depression at the initial time point. When their depression score was assessed over time, it appeared to plateau at a higher level than those reporting less severe abuse. This finding is consistent with and well-documented in the extant literature even among other trauma populations. For example, severity of abuse was correlated with severity of depression among a sample of intimate partner violence survivors (Dienemann, Boyle, Baker, Resnick, Wiederhorn, & Campbell, 2000), as well as a sample of working-class mothers with a history of childhood/adolescent sexual abuse (Bifulco, Brown, & Adler, 1991). Further, such dose-response patterns also complement a long line of research on cumulative abuse, revictimization, and polyvictimization. Inherent in the idea of revictimization is the notion of “cumulative trauma effect,” which posits that the cumulative number of different traumatic events predicts and exacerbates adverse mental and physical health sequelae beyond that accounted for by any single type of victimization (Follete, Polusny, Bechtle, & Naugle, 1996). Consistent with previous studies, our findings support the importance of offering prevention and intervention efforts to foster youth, especially those who report greater abuse severity.

In the present study, the majority of foster youth reported experiencing “much” positive change, with regard to increased compassion for others and enhanced self-efficacy, which is consistent with previous literature that positive change is common among trauma survivors (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). As hypothesized, youth with higher levels of self-efficacy at the initial time point experienced a decrease in depression, both at the initial time point and over time. Collectively, these findings suggest that the present sample developed a heightened sense of self-efficacy, which potentially enhanced their readiness to exit foster care and buffered them from developing depressive symptoms. The importance of perceived self-efficacy was first underscored in Bandura’s social-cognitive theory (1977), in which he explained that “[a]n efficacy expectation is the conviction that one can successfully execute the behavior required to produce the outcomes” (p. 193). This sense of human agency is a strong determinant of how much effort one will exert and how long one will persevere in the face of obstacles and challenges (Bandura, 1977). A strong conviction in self is crucial among foster youth who are likely deprived of parental support and/or guidance during this major life transition (Osterling & Hines, 2006).

Contrary to our expectation, youth’s initial compassion for others was neither associated with their initial depression score nor the decline in their depression over time. This finding indicates that compassion for others may not be a precipitating or maintaining factor in depression, at least in the current sample. Related research findings have been mixed. For example, using a cross-sectional design, McMillen and Fisher (1998) found that increased compassion for others was positively related to depressive symptoms. Individuals who continued to suffer from depressive symptoms also developed greater compassion for others, particularly toward those who had experienced similar suffering (McMillen & Fisher, 1998). It is possible that greater sensitivity toward the suffering of others render it difficult to change one’s pessimistic worldview that stemmed from their own trauma experience. Alternatively, individuals who continue to dwell on their negative experiences may have an attentional bias toward similar encounters of others, thereby increasing their level of sympathy toward others.

On the other hand, a different study observed that compassion for others served to buffer against physiological reactivity to stress (Cosley, McCoy, Saslow, & Epel, 2010). The authors explained that compassion for others could improve one’s wellbeing as it increases individuals’ perceived availability of social support and thereby enhances the effectiveness of social support received. Social support following trauma appears to be one of the strongest factors that thwart the development of mental health symptoms (e.g., Ozer, Best, Lipsey, & Weiss, 2003). Nonetheless, it is clear that this research area has yielded mostly contradictory findings, warranting further examination to elucidate whether this construct poses benefits or detriments to various trauma populations including foster youth.

To date, mixed findings regarding the relation between positive change and mental health outcomes have been documented (Linley & Joseph, 2004; Park & Helgeson, 2006). This inconsistency is also demonstrated in the current paper, wherein enhanced self-efficacy was observed to be an important predicting and maintaining factor of depressive symptoms; yet, similar conclusion cannot be made for increased compassion for others. The fact that enhanced self-efficacy was related to depression yet increased compassion was not related to depression illuminates specific mechanisms (i.e., enhanced self-efficacy) underlying posttrauma adjustment.

It is important to acknowledge several ways in which the present study is limited. Given the nature of secondary data analysis, we were limited by which positive change variables and mental health outcomes to analyze. Specifically, depression was the only mental health outcome assessed longitudinally in the original study; as such, we aimed to focus the paper solely on this outcome. The phenomenon of multifinality (for review, see Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996) is clearly documented in the literature, showing that similar risk factors may result in dissimilar outcomes, depending on the individual and the context. Although depression does not appear to be of concern in the present sample, other mental health concerns could not be ruled out. Incorporation of all possible adverse mental health outcomes (e.g., anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, dissociation) associated with an abuse history may provide a more comprehensive picture of psychological wellbeing of foster youth.

Second, only two indicators of positive change (i.e., enhanced self-efficacy and increased compassion) were available for analyses. Further, they were only measured during the initial interview. Additional longitudinal research that assesses positive change at each time point would better explicate change processes from victimization to positive change and psychological adjustment over time. Different domains of perceived positive change and their relation with mental health outcomes should be observed across time points as trauma survivors go through cyclical recovery phases and only certain positive change variables may be implicated in the recovery process. Taken together, the current findings, albeit interesting, should be considered as preliminary findings. Further longitudinal examination of other mental health factors and positive change variables is warranted to generate a more holistic and accurate understanding of posttrauma functioning.

Third, the use of self-reports, especially with regard to childhood trauma history, may introduce recall bias and socially desirable responding. Future replications may consider validating information from others in the participants’ network, such as their foster parents, guardians, or caseworkers. On a related note, the current study design prohibits causal statements to be made regarding the directionality among the variables of interest (i.e., adverse experiences, positive change, and depression). It was unclear whether the heightened sense of self-efficacy endorsed by this sample resulted from benefits via transitional programming, engagement in adaptive coping strategies, and socially desirable responding (in the Perceived Benefits Scale, for example), rather than due to their adverse experiences. Likewise, self-efficacy and depressive symptoms were assessed concurrently at the initial time point. The decline in depression could be explained by an increased sense of efficacy, as well as a host of variables not captured in this study such as engagement in adaptive coping strategies, regression to the mean, or expected declines in mental health symptoms. Additional replications should be done prospectively with at-risk samples to elucidate causal relationships among these variables. Lastly, the generalizability of the present study may be restricted by our sample of only foster youth from Missouri. There could be state-wide differences that emerge as a function of the foster care programs offered within each state. Replication with foster youth samples from different states is warranted to rule out such possible differences.

Despite its limitations, this study has important research and clinical implications for the field of positive change, trauma recovery, and mental health. In regard to research contribution, this study illustrates that different components of positive change could operate differentially in predicting mental health wellbeing in the aftermath of adversity. However, most extant research examined the relation between positive change and psychological outcome using an aggregated measure score instead of individual factors. This practice may obscure the ability to examine specific components of positive change that may be implicated in the recovery process. In this study, for example, we found that self-efficacy, but not compassion for others, was an important predictor of depression over time.

In addition, the current study, with its prospective design and two separate positive change indicators, represents an important attempt to advance the field of posttrauma positive change in the context of depression. An over-reliance on cross-sectional design may partially account for inconsistent findings regarding the relation between positive change and adverse mental health outcomes as observed in previous studies. The use of cross-sectional design also renders it inappropriate to make premature conclusions regarding the causal relation between positive change and psychological adjustment, especially given that perceived growth may take time to transpire (e.g., Helgeson et al., 2006). Further, considering that most positive change literature has focused on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, the current study is one of the few that has examined depression outcomes. This also highlights the importance to examine the link between positive change and depression as well as other posttrauma psychopathology (e.g., dissociation, somatization) in future studies.

To date, this study is the first known empirical study to examine the concept of positive change among foster care youth. For most adolescents, the transition to independence is an exciting and perhaps slightly nerve-wrecking phase of life. However, in light of their history of maltreatment, potential genetic susceptibility to emotional disorders, and nontraditional living background, foster youth leave the system of care “with the deck often already stacked against them” (Courtney et al., 2001, p. 714). Time and again, studies have shown that foster youth alumni face considerable challenges in various life domains including employment, housing stability, medical and mental health care, family formation, and crime involvement (Courtney & Dworsky, 2006; Courtney et al., 2001; Reilly, 2003), leaving them particularly vulnerable to developing psychopathology during this transition. It is imperative to provide these individuals supplementary assistance as they transition to self-sufficiency; however, it is not always clear which services would be most beneficial to this group of foster youth (Courtney et al., 2001). Close tracking of their changes, both positive and negative, is important to fully understand the type of assistance and sustenance that may be constructive as foster youth transition out of foster care and into adulthood.

By better understanding pathways to positive adjustment among trauma-exposed foster youth, intervention efforts can focus on strengthening relevant factors to enhance psychological wellbeing and to help these individuals explore avenues that may promote growth (McMillen & Fisher, 1998). Findings from the current study suggest that a sense of efficacy in the aftermath of trauma increase one’s growth and attenuates symptoms of depression. In fact, self-efficacy has been highlighted as a crucial ingredient or byproduct in clinical interventions developed for a myriad of presenting concerns. Consistent with the current finding, Benight and Bandura (2004) illustrated the importance of ‘perceived coping self-efficacy’ in the context of trauma recovery. Specifically, trauma survivors who believe in their ability to navigate personal and environmental stressors following the calamity typically showed reduced avoidant coping and increased psychological wellbeing.

Future prevention and intervention efforts for foster youth should be constructed and implemented to increase their self-efficacy, especially among those who are transitioning into independent living, in order to reduce their risk of developing depression. When treating foster youth, enabling a sense of agency should be done early, explicitly, and frequently as they may otherwise view the difficult treatment process, especially trauma exposure treatments, yet another defeat. To enhance the processing of efficacy-relevant information, therapy may employ enactive (i.e., guided/graduated in-vivo exposure), vicarious (i.e., social modeling of effective coping skills), and persuasive strategies (i.e., challenging cognitive distortions) that are specific to coping efficacies (Benight & Bandura, 2004, p. 1144). Finally, on a broader level, engaging foster youth in community-based leadership activities, social advocacy participation, or even involvement in foster care projects (e.g., to help plan and organize transitional programs) and decision-making (e.g., to serve on advisory council committee) can go a long way for facilitating youth empowerment and self-efficacy (e.g., Morton & Montgomery, 2011).

Acknowledgments

The data used in this study were obtained from the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, and have been used with their permission. Data were taken from the Mental Health Service Use Of Youth Leaving Foster Care (Voyages) 2001–2003 originally collected by Curtis McMillen, Lionel Scott, and Wendy Fran Auslander (McMillen, 2010). Funding for the project was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (Award Number: 1R01 MH 61404). The collector of the original data, the funder, NDACAN, Cornell University and their agents or employees bear no responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benight CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2004;42:1129–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace & Co; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bifulco A, Brown GW, Adler Z. Early sexual abuse and clinical depression in adult life. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;159:115–122. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns B, Phillips S, Wagner HR, Barth R, Kolko D, Campbell Y, Landsverk J. Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:960–970. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D. The conceptualization and analysis of change over time: An integrative approach incorporating Longitudinal Mean and Covariance Structures Analysis (LMACS) and Multiple Indicator Latent Growth Modeling (MLGM) Organizational Research Methods. 1998;1:421–483. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Developmental Psychopathology. 1996;8:597–600. [Google Scholar]

- Cosley BJ, McCoy SK, Saslow LR, Epel ES. Is compassion for others stress buffering? Consequences of compassion and social support for physiological reactivity to stress. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;46:816–823. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A. Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child & Family Social Work. 2006;11:209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Dworsky A, Ruth G, Keller T, Havlicek J, Bost N. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 19. Chicago: University of Chicago, Chapin Hall Center for Children; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Piliavin I, Grogan-Kaylor A, Nesmith A. Foster youth transitions to adulthood. A longitudinal view of youth leaving care. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program. 2001;80:685–717. Retrieved from http://www.cwla.org/articles/cwjabstracts.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Terao S, Bost N. Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Conditions of youth preparing to leave state care. Chicago: University of Chicago, Chapin Hall Center for Children; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dienemann J, Boyle E, Baker D, Resnick W, Wiederhorn N, Campbell J. Intimate partner abuse among women diagnosed with depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2000;21:499–513. doi: 10.1080/01612840050044258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follette VM, Polusny MA, Bechtle AE, Naugle AE. Cumulative trauma: The impact of child sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and spouse abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:25–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02116831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Conlon A, Glaser T. Positive and negative life changes following sexual assault. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1048–1055. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havalchak A, White CR, O’Brien K, Pecora PJ. Casey Family Programs Young Adult Survey 2006: Examining outcomes for young adults served in out-of-home care. Seattle, WA: Casey Family Programs; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Tomich P. A meta-analytic review of benefit finding and growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:797–816. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Meade CS, Kershaw TS, Milan S, Lewis JB, Ethier KA. Urban teens: Trauma, posttraumatic growth, and emotional distress among female adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:841–850. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG, Sörbom D. LISREL 8 [Computer software] Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S, Linley PA, Harris GJ. Understanding positive change following trauma and adversity: Structural clarification. Journal of Loss & Trauma: Interpersonal Perspectives on Stress & Coping. 2006;10:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Linley PA, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC. Mental Health Service Use of Youth Leaving Foster Care (Voyages) 2001–2003 [Dataset] 2010 Available from National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect Web site, http://www.ndacan.cornell.edu.

- McMillen JC, Fisher RH. The Perceived Benefit Scales: Measuring perceived positive life changes after negative events. Social Work Research. 1998;22(3):173–186. [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC, Scott LD, Zima BT, Ollie MT, Munson MR, Spitznagel EL. Use of mental health services among older youths in foster care. Psychiatry Services. 2004;55:811–817. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.7.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC, Zima BT, Scott LD, Auslander WF, Munson MR, Ollie MT, Spitznagel EL. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:88–95. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145806.24274.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerson DA, Grant KE, Carter JS, Kilmer RP. Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:949–964. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milam JE, Ritt-Olson A, Unger JB. Posttraumatic growth among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Morton M, Montgomery P. Youth empowerment programs for improving self-efficacy and self-esteem of adolescents. Campbell Systematic Reviews. 2011;5:1–79. [Google Scholar]

- Munson MR, McMillen JC. Natural mentoring and psychosocial outcomes among older transitioning from foster care. Child and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nietzsche F. The twilight of the idols and the anti-Christ: or how to philosophize with a hammer. Harmondsworth, London: Penguin; 1889/1990. [Google Scholar]

- Osterling KL, Hines AM. Mentoring adolescent foster youth: Promoting resilience during developmental transitions. Child and Family Social Work. 2006;11:242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(1):52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Helgeson VS. Introduction to the special section: Growth following highly stressful life events- current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:791–796. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecora PJ, Williams J, Kessler RC, Downs AC, O’Brien K, Hiripi E, Morello S. Assessing the effects of foster care: Early results from the Casey National Alumni Study. Seattle, WA: Casey Family Programs; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Powell S, Rosner R, Butollo W, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth after war: A study with former refugees and displaced people in Sarajevo. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:71–83. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly T. Transition from care: Status and outcomes of youth who age out of foster care. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program. 2003;82:727–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar AM, Keller TE, Courtney ME. Understanding social support’s role in the relationship between maltreatment and depression in youth with foster care experience. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16:102–113. doi: 10.1177/1077559511402985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare-Finch J, Lurie-Beck J. A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28:223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GR, Burnam A, Burns B, Cleary P, Rost KM. Major Depression Outcomes Module: User’s manual. Little Rock: University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GR, Kramer TL, Hollenberg JA, Mosley CL, Ross RL, Burnam A. Validity of the depression-arkansas (D-ARK) scale: A tool for measuring major depressive disorder. Mental Health Services Research. 2002;4:167–173. doi: 10.1023/a:1019763130150. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1019763130150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Trauma and transformation: Growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9:455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff JA, Taylor SE, Kemeny ME, Wyatt GE. Positive and negative effects of HIV infection in women with low socioeconomic resources. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:382–394. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn AA, Roesch SC, Aldridge AA. Stress-related growth in racial/ethnic minority adolescents: Measurement structure and validity. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2009;69:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) report: Preliminary estimates for FY 2010 as of June 2011. Washington, DC: Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau; 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2012, from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb. [Google Scholar]

- Walter LJ, Meresman JF, Kramer TL, Evans RB. The depression - arkansas scale: A validation study of a new brief depression scale in an HMO. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:465–481. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10137. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CR, O’Brien K, Pecora PJ, Englisht D, Williams JR, Phillips CM. Depression among alumni of foster care: Decreasing rates through improvement of experiences in care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2009;17:38–48. [Google Scholar]