Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 1

This second version was edited as suggested by the three referees and details are outlined in our response. A summary of these changes are:

Bootstrapped conditional probabilities were re-run with 10,000 iterations. This resulted in slightly different final values, although conclusions are unchanged

Several references were added about related studies

More details about the National Lakes Assessment sampling protocol were added.

A static copy of the dataset is now included with the repository at https://github.com/USEPA/Microcystinchla/raw/master/inst/extdata/nla_dat.csv

Corrected typos and unclear text

Added discussion about possible regional relationships

Clarified how measurements at the detection limit were handled

Abstract

Cyanobacteria harmful algal blooms (cHABs) are associated with a wide range of adverse health effects that stem mostly from the presence of cyanotoxins. To help protect against these impacts, several health advisory levels have been set for some toxins. In particular, one of the more common toxins, microcystin, has several advisory levels set for drinking water and recreational use. However, compared to other water quality measures, field measurements of microcystin are not commonly available due to cost and advanced understanding required to interpret results. Addressing these issues will take time and resources. Thus, there is utility in finding indicators of microcystin that are already widely available, can be estimated quickly and in situ, and used as a first defense against high levels of microcystin. Chlorophyll a is commonly measured, can be estimated in situ, and has been shown to be positively associated with microcystin. In this paper, we use this association to provide estimates of chlorophyll a concentrations that are indicative of a higher probability of exceeding select health advisory concentrations for microcystin. Using the 2007 National Lakes Assessment and a conditional probability approach, we identify chlorophyll a concentrations that are more likely than not to be associated with an exceedance of a microcystin health advisory level. We look at the recent US EPA health advisories for drinking water as well as the World Health Organization levels for drinking water and recreational use and identify a range of chlorophyll a thresholds. A 50% chance of exceeding one of the specific advisory microcystin concentrations of 0.3, 1, 1.6, and 2 μg/L is associated with chlorophyll a concentration thresholds of 23, 68, 84, and 104 μg/L, respectively. When managing for these various microcystin levels, exceeding these reported chlorophyll a concentrations should be a trigger for further testing and possible management action.

Keywords: Harmful Algal Blooms, Cyanotoxins, National Lakes Assessment, Conditional Probability Analysis, Cyanobacteria

Introduction

Over the last decade, numerous events and legislative activities have raised the public awareness of harmful algal blooms 1– 3. In response the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has recently released suggested microcystin (one of the more common toxins) concentrations that would trigger health advisories 4– 6. Additionally, the World Health Organization (WHO) has microcystin advisory levels for drinking water and for a range of recreational risk levels 7, 8. While these levels and associated advisories are likely to help mitigate the impacts from harmful algal blooms, they are not without complications.

One of these complications is that they rely on available measurements of microcystin. While laboratory testing (e.g., chromatography) remains the gold standard for quantifying microcystin concentrations in water samples, several field test kits have been developed. Even though field tests provide a much needed means for rapid assessment, they are not yet widely used and are moderately expensive (approximately $150–$200 depending on specific kit) with a limited shelf life (typically one year) 9, 10. Additionally, each technique requires nuanced understanding of the detection method (e.g., limit of detection, specific microcystin variants being measured, and sampling protocol).

Fortunately, cyanobacteria and microcystin-LR has been shown to be associated with several other, more commonly measured and well understood components of water quality that are readily assessed in the field 11. For instance, there are small or hand held fluorometers that measure chlorohpyll a. Additionally, chlorophyll a is a very commonly measured component of water quality that is also known to be positively associated with microsystin-LR concentrations 12, 13. Recently, Yuan et al. 13 explored these associations in detail and controlled for other related variables. In their analysis they find that total nitrogen and chlorophyll a show the strongest association with microcystin. Furthermore, they identify chlorophyll a and total nitrogen concentrations that are associated with exceeding 1 µg/L of microcystin. These findings suggest that chlorophyll a concentrations could also track the new USEPA microcystin health advisory levels for drinking water. Identifying this association would provide an important tool for water resource managers to help manage the threat to public health posed by cHABs and would be especially useful in the absence of measured microcystin concentrations.

In fact, this is a similar tact to the World Health Organization who, in addition to advisory levels for microcystin, have also proposed related advisory levels for cyanobacteria abundance and chlorophyll a 7, 8. The chlorophyll a concentrations proposed by the WHO are for low (< 10 µg/L), moderate (between 10 and 50 µg/L, high (between 50 and 5000 µg/L), and very high risk (>5000 µg/L) 8. While these advisories have proven to be useful tools they do suffer from being coarse, broad, and have been found to overestimate actual risk 14.

In this paper we build on these past efforts and utilize the National Lakes Assessment (NLA) data and identify chlorophyll a concentrations that are associated with higher probabilities of exceeding several microcystin health advisory concentrations 6, 8, 15. We build on past studies by exploring associations with the newly announced advisory levels and by also applying a different method, conditional probability analysis. Utilizing different methods strengthens the evidence for suggested chlorophyll a levels that are associated with increased risk of exceeding the health advisory levels as those levels are not predicated on a single analytical method. So that others may repeat or adjust this analysis, the data, code, and this manuscript are freely available via https://github.com/USEPA/microcystinchla.

Methods

Data

We used the 2007 NLA chlorophyll a and microcystin-LR concentration data 15. These data represent a snapshot of water quality from the summer of 2007 for the conterminous United States and were collected as part of an ongoing probabilistic monitoring program 15. Water quality data, including chlorophyll a and microcystin-LR were obtained via an integrated sample taken from the surface of the lake down to 2 meters. Samples were taken at the same time from the index site (e.g. near the centroid of the lake) and these provide the source for both chlorophyll a and microcystin-LR 15.

For our analysis we only used samples that were part of the probability sampling design (i.e. no reference samples) and from the first visit to the lake (e.g. some lakes were sampled multiple times). The detection limit for microcystin-LR was 0.05 µg/L. Approximately 67% of lakes reported microcystin-LR at the detection limit. For this analysis we retained these values as removing them would erroneously reduce the confidence intervals around the conditional probabilities. Data on chlorophyll a and microcystin-LR concentrations are available for 1028 lakes.

Analytical methods

We used a conditional probability analysis (CPA) approach to explore associations between chlorophyll a concentrations and World Health Organization (WHO) and USEPA microcystin health advisory levels 17. Many health advisory levels have been suggested ( Table 1), but lakes with higher microcystin-LR concentrations in the NLA were rare. Only 1.16% of lakes sampled had a concentration greater than 10 µg/L. Thus, for this analysis we focused on the microcystin concentrations that are better represented in the NLA data. These were the USEPA children’s (i.e. bottle fed infants to pre-school age children) drinking water advisory level of 0.3 µg/L (USEPA Child), the WHO drinking water advisory level of 1 µg/L (WHO Drinking), the USEPA adult (i.e. beyond pre-school aged individuals) drinking water advisory level of 1.6 µg/L (USEPA Adult), and the WHO recreational, low probability of effect advisory level of 2 µg/L (WHO Recreational).

Table 1. Various microcystin health advisory concentrations from the USEPA and World Health Organization.

| Source | Type | Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| USEPA | Child Drinking Water Advisory | 0.3 µg/L |

| WHO | Drinking Water | 1 µg/L |

| USEPA | Adult Drinking Water Advisory | 1.6 µg/L |

| WHO | Recreational: Low Prob. of Effect | 2–4 µg/L |

| WHO | Recreational: Moderate Prob. of Effect | 10–20 µg/L |

| WHO | Recreational: High Prob. of Effect | 20–2000 µg/L |

| WHO | Recreational: Very High Prob. of Effect | >2000 µg/L |

Conditional probability analysis provides information about the probability of observing one event given another event has also occurred. For this analysis, we used CPA to examine how the conditional probability of exceeding one of the health advisories changes as chlorophyll a increases in a lake. We expect to find higher chlorohpyll a concentrations to be associated with higher probabilities of exceeding the microcystin health advisory levels. We also calculated bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CI) using 10,000 bootstrapped samples. Thus, to identify chlorophyll a concentrations of concern we identified the value of the upper 95% CI across a range of conditional probabilities of exceeding each health advisory level. Using the upper confidence limit to identify a threshold is justified as it ensures that a given threshold is unlikely to miss a microcystin exceedance.

As both microcystin-LR and chlorophyll a values were highly right skewed, a log base 10 transformation was used. Additional details of the specific implementation are available at https://github.com/USEPA/microcystinchla. A more detailed discussion of CPA is beyond the scope of this paper, but see Paul et al. 18 and Hollister et al. 19 for greater detail. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.2.3 and code and data from this analysis are freely available as an R package at https://github.com/USEPA/microcystinchla.

Lastly, we assessed the ability of these chlorophyll a thresholds to predict microcystin exceedance. We used error matrices and calculate total accuracy as well as the proportion of false negatives. Total accuracy is the total number of correct predictions divided by total observations. The proportion of false negatives is the total number of lakes that were predicted to not exceed the microcystin guidelines but actually did, divided by the total number of observations.

Results

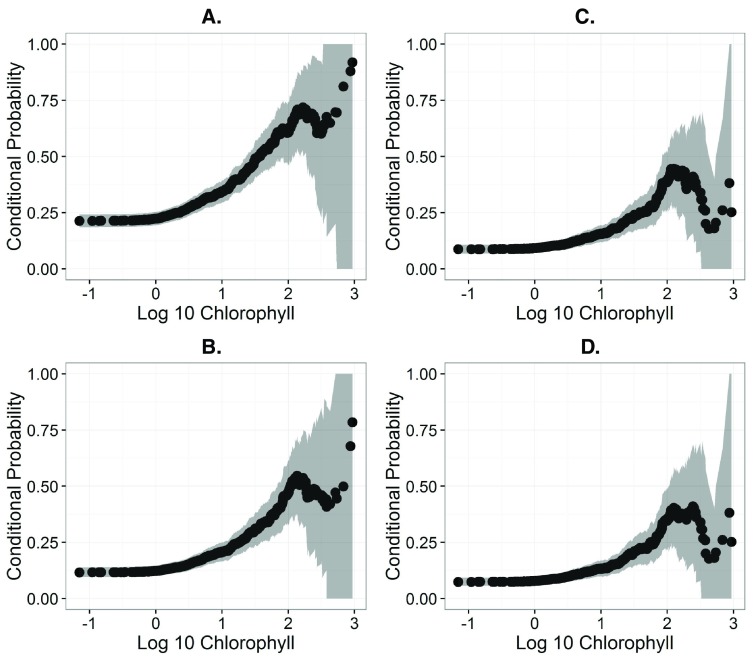

In the 2007 NLA, microcystin-LR concentrations ranged from 0.05 to 225 µg/L. Microcystin-LR concentrations of 0.05 µg/L represent the detection limits. Any value greater than that indicates the presence of microcystin-LR. Of those lakes with microcystin-LR, the median concentration was 0.51 µg/L and the mean was 3.17 µg/L. Of all lakes sampled, 21% of lakes exceeded the USEPA Child level, 8.8% of lakes exceeded the USEPA Adult level, 11.7% of lakes exceeded the WHO Drinking level, and 7.3% of lakes exceeded the WHO Recreational level. Chlorophyll a, ranged from 0.07 to 936 µg/L and this captures the range of trophic states from oligotrophic to hypereutrophic. All lakes had detectable levels of chlorophyll a. The median concentration was 7.79 µg/L and the mean was 29.63 µg/L. The association between chlorophyll a and the upper confidence interval across a range of conditional probability values are shown in Table 2. Specific chlorophyll a concentrations that are associated with greater than even odds of exceeding the advisory levels were 23, 68, 84, and 104 µg/L for 0.3, 1.0, 1.6, and 2.0 µg/L advisory levels, respectively ( Table 2 & Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conditional probability plots showing association between the probability of exceeding various microcystin-LR (MLR) health advisory Levels.

A.) Plot for USEPA Child (0.3 µ g/L). B.) Plot for WHO Drinking (1 µ g/L). C.) Plot for USEPA Adult (1.6 µ g/L). D.) Plot for WHO Recreational (2 µ g/L).

The chlorophyll a cutoffs may be used to predict whether or not a lake exceeds the microcystin health advisories. Doing so allows us to compare the accuracy of the prediction as well as evaluate false negatives. Total accuracy of the four cutoffs predicting microcystin exceedances were 74% for the USEPA children’s drinking water advisory, 86% for the WHO drinking water advisory, 89% for the USEPA adult drinking water advisory, and 91% for the WHO recreational advisory ( Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, & Table 6). However, total accuracy is only one part of the prediction performance with which we are concerned.

Table 2. Chlorophyll a concentrations that are associated with a 50% probability of exceeding a microcystin health advisory concentration.

| Cond.

Probability |

USEPA Child

(0.3 µg/L) |

WHO Drink

(1 µg/L) |

USEPA Adult

(1.6 µg/L) |

WHO Recreational

(2 µg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 1 |

| 0.2 | 0.07 | 4 | 12 | 17 |

| 0.3 | 3 | 17 | 32 | 45 |

| 0.4 | 11 | 37 | 68 | 77 |

| 0.5 | 23 | 68 | 84 | 104 |

| 0.6 | 39 | 97 | 115 | 185 |

| 0.7 | 66 | 126 | 871 | 871 |

| 0.8 | 116 | 271 | 871 | 871 |

| 0.9 | 170 | 516 | 871 | 871 |

Table 3. Confusion matrix comparing chlorophyll a predicted exceedences (rows) versus real exceedances (columns) for the USEPA childrens drinking water advisory.

| Not Exceed | Exceed | Row Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Exceed | 643 | 95 | 738 |

| Exceed | 168 | 122 | 290 |

| Column Totals | 811 | 217 | 1028 |

Table 4. Confusion matrix comparing chlorophyll a predicted exceedences (rows) versus real exceedances (columns) for the WHO drinking water advisory.

| Not Exceed | Exceed | Row Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Exceed | 841 | 78 | 919 |

| Exceed | 66 | 43 | 109 |

| Column Totals | 907 | 121 | 1028 |

Table 5. Confusion matrix comparing chlorophyll a predicted exceedences (rows) versus real exceedances (columns) for the USEPA adult drinking water advisory.

| Not Exceed | Exceed | Row Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Exceed | 884 | 57 | 941 |

| Exceed | 53 | 34 | 87 |

| Column Totals | 937 | 91 | 1028 |

Table 6. Confusion matrix comparing chlorophyll a predicted exceedences (rows) versus real exceedances (columns) for the WHO recreational water advisory.

| Not Exceed | Exceed | Row Totals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Exceed | 908 | 51 | 959 |

| Exceed | 45 | 24 | 69 |

| Column Totals | 953 | 75 | 1028 |

When using the chlorophyll a cutoffs as an indicator of microcystin exceedances, the error that should be avoided is predicting that no exceedance has occurred when in fact it has. In other words, we would like to avoid Type II errors and minimize the proportion of false negatives. For the four chlorophyll a cut-offs we had a proportion of false negatives of 9%, 8%, 6%, and 5% for the USEPA children’s, the WHO drinking water, the USEPA adult, and the WHO recreational advisories, respectively. In each case we missed less than 10% of the lakes that in fact exceeded the microcystin advisory. While this method performs well with regard to the false negative percentage, it is possible that is a relic of the NLA dataset and testing with additional data would allow us to confirm this result.

Discussion

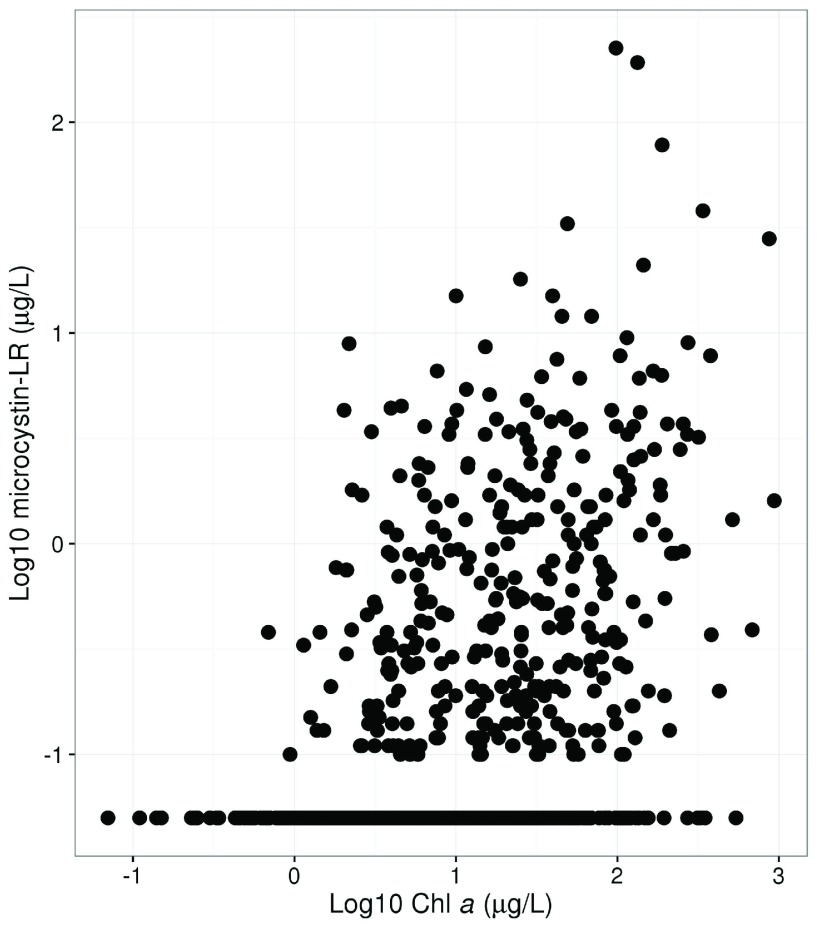

The log-log association between microcystin-LR and chlorophyll a indicates that, in general, higher concentrations of microcystin-LR almost always co-occur with higher concentrations of chlorophyll a yet the inverse is not true ( Figure 2). Higher chlorophyll a is not necessarily predictive of higher microcystin-LR concentrations; however, chlorophyll a may be predictive of the probability of exceeding a certain threshold.

Figure 2. Scatterplot showing association between chlorophyll a and microcystin-LR.

Indeed, the probability of exceeding each of the four tested health advisory levels increased as a function of chlorophyll a concentration ( Figure 1). We used this association to identify chlorophyll a concentrations that were associated with a range of probabilities of exceeding a given health advisory level ( Table 2). For the purposes of this discussion we focus on a conditional probability of 50% or greater (i.e., greater than even odds to exceed a health advisory level). The 50% conditional probability chlorophyll a thresholds represents 28.6%, 11%, 8.9%, and 7.2% of sample lakes for the USEPA Child, the WHO Drinking, the USEPA Adult, and the WHO recreational levels, respectively.

There are numerous possible uses for the chlorophyll a and microcystin advisory cut-off values. First, in the absence of microcystin-LR measurements, exceedence of the chlorophyll a concentrations could be a trigger for further actions. Given that there is uncertainity around these chlorophyll a cutoffs the best case scenario would be to monitor for chlorophyll a and in the event of exceeding a target concentration take water samples and have those samples tested for microcystin-LR.

A second potential use is to identify past bloom events from historical data. As harmful algal blooms are made up of many species and have various mechanisms responsible for adverse impacts (e.g., toxins, hypoxia, odors), there is no single definition of a bloom. For cHABs, one approach has been to utilize phycocyanin to screen for or identify bloom events 20. This is a useful approach, but phycocyanin is not always available, thus limiting its utility especially for examining historical data. Using our chlorophyll a cutoffs provides a value that is also associated with microcystin-LR and can be used to classify lakes, from past surveys, as having bloomed.

The values we propose are national and may miss regional variation in water quality, including, chlorophyll a and microcystin-LR 22. A set of regional conditional probabilities would be interesting; however, limiting the analysis to the data available per region would make interpretation difficult. The sample size for each of the regional conditional probabilities would be reduced and the number of lakes in each region that exceed the microcystin values would also be reduced. Thus, our confidence in the conditional probabilities would be less (i.e. greatly increased confidence intervals) and the relationships less pronounced as we have fewer lakes on which to base the probabilities. Thus, this dataset is best for making national scale recommendations.

There are two other limitations with the 2007 National Lakes Assessment dataset. First, it represents a single sample from a lake and does not capture temporal dynamics. Second, validation of the predictions with the 2007 data alone would be challenging as the data would need to be subset and this would only sever to increase the uncertainty of our conditional probabilities, reducing our ability to validate the presence of microcystin-LR. The 2012 National Lakes Assessment would be ideal for this task. However, as of this writing, the 2012 National Lakes Assessment data are not public. When these data are released, a validation of this approach can be completed then.

Lastly, using chlorophyll a is not meant as a replacement for testing of microcystin-LR or other toxins. It should be used when other, direct measurements of cyanotoxins are not available. In those cases, which are likely to be common at least in the near future, using a more ubiquitous measurement such as chlorophyll a will provide a reasonable proxy for the probability of exceeding a microcystin health advisory level and provide better protection against adverse effects in both drinking and recreational use cases.

Data and software availability

Data and latest source code

Archived data and source code at time of publication

License

Creative Commons Zero 1.0: http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anne Kuhn, Bryan Milstead, John Kiddon, Joe LiVolsi, Tim Gleason, Wayne Munns, and Leslie D’Anglada for constructive reviews of this paper. Special thanks to Jason Marion, Alan Wilson, and Zofia Taranu for reviews of the submitted manuscript. This paper has not been subjected to Agency review. Therefore, it does not necessary reflect the views of the Agency. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This contribution is identified by the tracking number ORD-015143 of the Atlantic Ecology Division, Office of Research and Development, National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, US Environmental Protection Agency.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 2; referees: 1 approved

References

- 1. Jetoo S, Grover VI, Krantzberg G: The Toledo drinking water advisory: Suggested application of the water safety planning approach. Sustainability. 2015;7(8):9787–9808. 10.3390/su7089787 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rinta-Kanto JM, Konopko EA, DeBruyn JM, et al. : Lake Erie Microcystis: Relationship between microcystin production, dynamics of genotypes and environmental parameters in a large lake. Harmful Algae. 2009;8(5):665–673. 10.1016/j.hal.2008.12.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Amendments Act: Harmful Algal Bloom and Hypoxia Research and Control Amendments Act of 2014.2014;S. 1254 Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 4. McElhiney J, Lawton LA: Detection of the cyanobacterial hepatotoxins microcystins. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;203(3):219–230. 10.1016/j.taap.2004.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zurawell RW, Chen H, Burke JM, et al. : Hepatotoxic cyanobacteria: a review of the biological importance of microcystins in freshwater environments. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2005;8(1):1–37. 10.1080/10937400590889412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. US EPA: Drinking water health advisory for the cyanobacterial microcystin toxins. EPA-820-R-15100.2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization: Cyanobacterial toxins: Microcystin-LR in drinking-water.Background document for development of WHO guidelines for drinking-water quality Geneva, Switzerland. World Health Organization, 2nd ed. Geneva.2003. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chorus I, Bartram J: Toxic cyanobacteria in water: A guide to their public health consequences, monitoring and management.World Health Organization.1999. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 9. James R, Gregg A, Dindal A, et al. : Environmental technology verification report: Abraxis microcystin test kits. Online document. Accessed online: June 22,2011. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aranda-Rodriguez R, Jin Z, Harvie J, et al. : Evaluation of three field test kits to detect microcystins from a public health perspective. Harmful Algae. 2015;42:34–42. 10.1016/j.hal.2015.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yuan LL, Pollard AI: Deriving nutrient targets to prevent excessive cyanobacterial densities in U.S. lakes and reservoirs. Freshwater Biol. 2015;60(9):1901–1916. 10.1111/fwb.12620 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pip E, Bowman L: Microcystin and algal chlorophyll in relation to nearshore nutrient concentrations in Lake Winnipeg, Canada. Environ Pollut. 2014;3(2):p36 10.5539/ep.v3n2p36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yuan LL, Pollard AI, Pather S, et al. : Managing microcystin: Identifying national-scale thresholds for total nitrogen and chlorophyll a. Freshwater Biol. 2014;59(9):1970–1981. 10.1111/fwb.12400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Loftin KA, Graham JL, Hilborn ED, et al. : Cyanotoxins in inland lakes of the United States: Occurrence and potential recreational health risks in the ePA national lakes assessment 2007. Harmful Algae. 2016;56:77–90. 10.1016/j.hal.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. US EPA: National lakes assessment: A collaborative survey of the nation’s lakes. EPA 841-R-09-001.2009. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 16. USEPA: Survey of the nation’s lakes field operations manual. EPA841-B-07-004.2007. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paul JF, Munns WR, Jr: Probability surveys, conditional probability, and ecological risk assessment. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2011;30(6):1488–1495. 10.1002/etc.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Paul JF, McDonald ME: Development of empirical, geographically specific water quality criteria: A conditional probability analysis approach. J Am Water Resour Assoc. 2005;41(5):1211–1223. 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2005.tb03795.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hollister JW, Walker HA, Paul JF: CProb: a computational tool for conducting conditional probability analysis. J Environ Qual. 2008;37(6):2392–2396. 10.2134/jeq2007.0536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller TR, Beversdorf L, Chaston SD, et al. : Spatiotemporal molecular analysis of cyanobacteria blooms reveals Microcystis--Aphanizomenon interactions. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marion JW, Lee J, Wilkins JR 3rd, et al. : In vivo phycocyanin flourometry as a potential rapid screening tool for predicting elevated microcystin concentrations at eutrophic lakes. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(8):4523–4531. 10.1021/es203962u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beaver JR, Manis EE, Loftin KA, et al. : Land use patterns, ecoregion, and microcystin relationships in U.S. lakes and reservoirs: A preliminary evaluation. Harmful Algae. 2014;36:57–62. 10.1016/j.hal.2014.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wagner T, Soranno PA, Webster KE, et al. : Landscape drivers of regional variation in the relationship between total phosphorus and chlorophyll in lakes. Freshwater Biol. 2011;56(9):1811–1824. 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2011.02621.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hollister JW, Kreakie BJ: Associations between chlorophyll a and various microcystin health advisory concentrations. Zenodo. 2016. Data Source [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]