Abstract

Introduction:

Based on the principles of Pavlovian learning and extinction, cue exposure therapy (CET) involves repeated exposure to substance-associated cues to extinguish conditioned cravings and reduce the likelihood of relapse. The efficacy of CET is predicated on successful extinction, yet the process of extinction in CET trials has rarely been demonstrated. This study explored the extinction process using a cue-reactivity paradigm in smokers undergoing multiple CET sessions as part of a comprehensive smoking cessation treatment.

Methods:

The sample comprised 76 moderately dependent, treatment-seeking smokers who completed at least 4 CET sessions and 6 counseling sessions. The CET and counseling sessions were scheduled twice weekly, and participants began using transdermal nicotine replacement therapy on their quit day, which occurred prior to initiation of CET. Each CET session consisted of presentation of 140 images on a computer screen, with self-reported craving as the primary measure of cue reactivity.

Results:

Mixed-model analyses revealed a progressive decline in cue-provoked craving both within and across 6 sessions of CET. Moderator analyses showed that the decline in craving was greatest among those who displayed initial cue reactivity.

Conclusions:

These data are consistent with the premise that CET can produce extinction of laboratory-based cue-provoked smoking cravings and highlight important individual differences that may influence extinction. Implications for conducting cue exposure research and interventions are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Craving plays an important role in smoking and relapse (Brandon, Vidrine, & Litvin, 2007; Tiffany, Warthen, & Goedeker, 2009), which makes effective management of craving a critical goal of smoking cessation interventions (Ferguson & Shiffman, 2009; Tiffany & Wray, 2012). Episodic craving, also referred to as cue-induced craving, is conceptualized as phasic increases in the urge to smoke, typically provoked by situational cues (Ferguson & Shiffman, 2009). Cue-induced craving has been shown to predict relapse and can persist even after the tonic, abstinence-induced craving declines following a quit attempt (Shadel et al., 2011; Shiffman et al., 1996; Shiffman, Paty, Gnys, Kassel, & Hickcox, 1996b; Shiffman et al., 1997). In laboratory studies, exposure of smokers to cigarette cues and negative affect (NA) cues reliably elicits strong subjective cravings (Brody et al., 2002; Carter et al., 2006; Carter & Tiffany, 1999; Conklin & Perkins, 2005; Heckman et al., 2013; Juliano & Brandon, 1998). Importantly, cue-provoked cravings elicited in the laboratory can be predictive of smoking behavior (Ditre et al., 2012; Waters et al., 2004), which underscores the clinical significance of the construct (see Perkins, 2009, 2012; Tiffany & Wray, 2009; and Wray et al., 2013 for a thorough discussion of this issue).

Models of substance use posit that cue reactivity reflects classical conditioning (Pavlov, 1927) in which repeated pairing of conditioned stimuli (e.g., smoking cues) with unconditioned stimuli (e.g., nicotine) eventually produce conditioned responses in the form of subjectively experienced urges or cravings to smoke and physiological reactivity (see Baker et al., 2004; Brandon et al., 2007). Such a conclusion is bolstered by demonstrations in laboratory studies that neutral stimuli repeatedly paired with drug use eventually elicit conditioned responses that are consistent with responses observed in cue-reactivity studies, namely craving and physiological reactivity (Foltin & Haney, 2000; Lazev, Herzog, & Brandon, 1999; Ternes et al., 1982). An important clinical implication of these findings is that such conditioned responses could be attenuated via extinction procedures. That is, repeated presentation of drug-related cues, or cue exposure, in the absence of the unconditioned stimulus (i.e., the ingested drug) should lead to diminished conditioned responses, including craving to the drug-related stimuli. Extinction of cravings to drug stimuli is expected to result in reduction of relapse.

To the degree that conditioned craving inhibits initial cessation and maintenance of abstinence, extinction-based treatment should have clinical efficacy (Monti & Rohsenow, 1999). However, cue exposure therapy (CET) for treatment of substance use has shown little long-term clinical efficacy (Conklin & Tiffany, 2002), despite evidence of posttreatment decreases in drug and alcohol cravings or consumption (Childress, McLellan, & O’Brien, 1986; Drummond & Glautier, 1994; Götestam & Melin, 1983; Rankin, Hodgson, & Stockwell, 1983; Stasiewicz et al., 1997). There have been few studies of CET applied to smoking cessation per se (Corty & McFall, 1984; Niaura et al., 1999), with similarly disappointing clinical outcomes to those of drug and alcohol treatment. Research testing the effects of multiple cue exposure trials on cue-provoked craving to smoke has been limited by small sample sizes and the use of participants who were not attempting to quit smoking. The cue exposure procedures across these studies have consistently induced craving to smoke, and some procedures have resulted in reductions in craving consistent with extinction (Collins, Nair, & Komaroff, 2011; Kamboj et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2004). However, craving ratings remained unchanged across cue exposure trials in two studies (Miranda, Rohsenow, Monti, Tidey, & Ray, 2008; Vinci, Copeland, & Carrigan, 2012), and one study observed craving reduction following the initial session, with no changes in the subsequent sessions (LaRowe, Saladin, Carpenter, & Upadhyaya, 2007). In sum, to date, laboratory research on cue exposure has demonstrated some evidence of extinction; however, the use of nontreatment-seeking participants has limited the generalizability of these findings to clinical populations, and the extinction process among individuals attempting to quit smoking remains poorly understood.

Improving the efficacy of CET requires an understanding of the extinction process itself, and, minimally, verification that extinction indeed occurs across CET sessions in an adequately powered study of a clinical sample of participants receiving treatment for tobacco dependence. This study examined within- and between-session changes in cue-provoked craving in smokers undergoing multiple CET sessions as part of a comprehensive smoking cessation treatment. We hypothesized that we would find progressively reduced craving reactivity to smoking cues (compared to neutral cues) across CET sessions, and possibly within CET sessions. We also tested whether similar reduction would be found to NA cues. Moreover, we examined several potential moderator variables. Specifically, we hypothesized that craving reduction would be greater among smokers who displayed initial reactivity to smoking cues (cue responders) and who did not smoke between CET sessions. We also tested the effects of nicotine dependence and gender on craving reduction.

METHODS

Participants

Cigarette smokers were recruited from the community for an intervention study examining the value of adding extinction cues (see Brooks & Bouton, 1994; Collins & Brandon, 2002; Stasiewicz, Brandon, & Bradizza, 2007) to CET for treating tobacco dependence. The following inclusion criteria were used: (a) age 18–60 years; (b) smoking at least 15 cigarettes/day; (c) breath carbon monoxide (CO) reading of at least 10 ppm; (d) smoking daily for at least one year; (e) fluent in English; (f) not enrolled in another smoking cessation program; and (g) not currently, nor in the past month, using pharmacotherapy for treatment of nicotine dependence. Because participants were provided transdermal nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), exclusion criteria included: pregnant or breast feeding, high blood pressure not controlled with medication, heart disease, and allergy or adverse reaction to nicotine patches. Participants were paid $5 for attending the first CET session, with payment increasing by $5 for each subsequent session.

Of the 159 treatment-seeking smokers who provided informed consent, 143 began treatment and 100 completed at least 4 CET sessions. Due to an error in the data acquisition program, most of the CET sessions’ craving data were inadvertently deleted for 24 consecutive participants. Therefore, the final sample of this study comprised 76 smokers who had full data for at least 4 sessions (including 36 who had data for all 6 sessions). Their key demographic and smoking-related variables are provided in Table 1. Noncompleters did not differ from completers on any baseline demographics or smoking variables.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Smoking Variables (N = 76)

| Demographic characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, M (SD) | 47.0 (9.4) |

| % Women | 58.4 |

| Race (%) | |

| Caucasian | 71.4 |

| African American | 19.5 |

| Other | 9.1 |

| Hispanic ethnicity (%) | 9.1 |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Married | 46.8 |

| Single | 33.8 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 19.5 |

| Education (%) | |

| High school degree | 20.8 |

| Some college or tech school | 54.6 |

| >Four-year college | 15.6 |

| Smoking variables | |

| Number of cigarettes/day, M (SD) | 25.2 (9.5) |

| Number of years smoke daily, M (SD) | 27.5 (10.3) |

| FTND total score | 5.7 (2.1) |

| Previous quit attempts, median (range) | 3.0 (0–40) |

| Previous longest abstinence (%) | |

| <1 day | 11.7 |

| 1–9 days | 24.7 |

| 2–6 weeks | 9.1 |

| 2–12 months | 36.4 |

| >12 months | 18.2 |

Note. FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.

Procedure

This study was approved by the university’s institutional review board, and all participants provided informed consent after receiving descriptions of the study content. Participants underwent a comprehensive smoking cessation intervention that lasted approximately 4 weeks and included 8 biweekly counseling sessions, 6 biweekly CET sessions, and transdermal NRT. The 15–30-min counseling sessions consisted of individual, face-to-face, standard cognitive–behavioral coping skills training that has been shown to be efficacious (e.g., Brandon, Copeland, & Saper, 1995; Brandon et al., 2003; Brandon, Zelman, & Baker, 1987; Zelman, Brandon, Jorenby, & Baker, 1992). NRT was distributed in the first session, with instructions to begin using the first patch the night before or the morning of the target quit day (counseling Session 2), which occurred prior to initiation of CET. The first 2 sessions consisted of counseling only. Beginning with counseling Session 3, CET sessions were conducted immediately before each of the counseling sessions. All participants received an 8-week treatment course of NRT that consisted of 4 weeks of 21mg/day, 2 weeks of 14mg/day, and 2 weeks of 7mg/day. NRT continued past the last treatment session. As recommended by the Clinical Practice Guideline (Fiore et al., 2008), NRT was included to enhance clinical outcomes, treatment retention, and compliance. In particular, we wanted to minimize smoking between CET sessions. Importantly, several studies have shown that transdermal nicotine does not itself impede cue reactivity (e.g., Tiffany, Cox, & Elash, 2000; Waters et al., 2004).

Upon arrival to each CET session, participants were seated in a comfortable chair in a sound-attenuated room. Each CET session comprised four extinction sets. Each set consisted of three blocks, including presentation of three neutral images followed by two smoking image blocks and one NA image block. Each image was presented for 12 s on a computer screen with 2 s between images. The neutral cues comprised pictures selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, 1995) and included objects, people, and situations that have been rated as neither pleasant, unpleasant, or arousing. Each smoking image block contained 12 smoking-related images that have elicited substantial craving reports in prior research (e.g., Carter et al., 2006; Gilbert & Rabinovitch, 1998; Stritzke et al., 2004). We also incorporated four photographs of personally relevant smoking-related cues into each stimuli set. Participants were provided digital cameras and instructed to take pictures of people, places, and things that increase their craving to smoke. Such images have been found to elicit greater cue reactivity than stock smoking images (Conklin, 2006). Each smoking-related set also included the handling and smelling of a cigarette (their own brand), and in vivo exposure to other smoking-related products (i.e., ashtray, lighter, pack of cigarettes) simultaneous with picture viewing. The middle block of each set contained eight NA-inducing images (four sadness and four anxiety). The affect images were drawn from IAPS (Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention, 1995). NA cues served as distal cues to induce negative mood, which has been shown to increase craving (Conklin & Perkins, 2005; Heckman et al., 2013) and precipitate relapse (Brandon, Tiffany, Obremski, & Baker, 1990; Shiffman et al., 1996). Although we considered also including positive affect cues, we opted not to, because of their less consistent association with craving (e.g., Shiffman et al., 2012, 2013) as well as concerns about increasing the duration and participant burden of the intervention sessions. The four sets each included the same distribution of image types in different orders. The order of the four sets differed across the CET sessions and was counterbalanced across participants. Each CET session lasted approximately 75min. In summary, the cue sets, which included images of smoking, personal smoking, and NA cues, as well as in vivo smoking cues were constructed to elicit maximal craving.

As the independent variable of the parent study, one half of the participants underwent CET sessions in the presence of an extinction cue, which was hypothesized to improve the generalizability of extinction across contexts. As expected, the extinction cue did not influence the extinction process itself; therefore, we collapsed across conditions for this report. Results from the parent study (including clinical outcomes) will be reported elsewhere.

Measures

Demographics and Smoking-Related Variables

Baseline measures included a demographic and smoking history questionnaire; the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991) and other self-report measures not used in the current study. For the purpose of examining individual difference factors, participants’ cessation status was based upon continuous abstinence throughout the treatment (breath CO verified at each CET session). All participants were classified as either “quit” (n = 50) or “not quit” (n = 26). Of those classified as “not quit,” 35% smoked an average of 3 cigarettes/day on less than 5 days, 42% smoked an average of 5.5 cigarettes/day on an average of 12 days, and almost all reduced daily quantity smoked and continued to make quit attempts throughout treatment.

Cue-Reactivity Measures

A computer input device was used to rate craving in response to images presented on a computer screen. The ratings consisted of three-item Visual Analog Scale (VAS), with scores ranging from 0 to 20. The following items were included: (a) How strong is your urge/desire to smoke right now; (b) How strong was your strongest urge/desire to smoke; and (c) Overall, how strong was your urge/desire to smoke; using the anchors “not at all” and “extremely strong.” The three-item craving measure has demonstrated equivalent psychometric properties to longer craving scales, but it is more appropriate for studies that require frequent craving assessment (Kozlowski, Pillitteri, Sweeney, & Whitfield, 1996). The three VAS scores were highly correlated; therefore, a craving mean score was used in all analyses. Mean coefficient alpha reliability for the three-item scale was .993. Craving ratings were collected following presentation of the neutral images, first smoking images block, NA images block, and second smoking images block. For the purposes of examining individual difference factors, cue responders (n = 56; 74% of sample) were defined as participants whose mean craving rating in response to smoking cues was at least one point higher than their mean craving rating in response to neutral cues during the first session. The one-point difference criterion has been used in previous research (Shiffman et al., 2003), and it represents 0.27 SDs of this index. We also collected secondary reactivity measures of affective and psychophysiological responses that are not the focus of this study.

RESULTS

Overview of Analyses

Craving ratings used in this analyses included: neutral image block ratings, NA block ratings, and the average of the two smoking image blocks ratings. Hence, one neutral image craving score, one NA image craving score, and one smoking image craving score were calculated for each of the four sets of each cue exposure session. This procedure allowed for examination of craving patterns both across and within CET sessions.

To examine changes in craving across and within CET sessions, we used mixed-model repeated measures analyses with a first-order autoregressive covariance structure. These models included fixed effects for Session (1–6), Set (1–4), and cue type (neutral, NA, and smoking), and the interaction of these three factors with set nested within session as a random effect. Two interactions were the primary focus of the analyses. A set × cue type interaction showing declining craving responses to smoking or NA images relative to neutral images would be consistent with within-session extinction. A session × cue type interaction showing a similar declining pattern would be consistent with across-session extinction. Significant interactions were explored with interaction tests between pairs of cue types (i.e., smoking vs. neutral, NA vs. neutral, smoking vs. NA).

Moderation effects of four individual difference factors upon reduction in craving were examined as mentioned previously with two adjustments. Craving ratings were collapsed across the four sets within each session, and separate models were conducted for smoking relative to neutral cues and NA relative to neutral cues. These mixed-model repeated measure analyses included fixed effects for session, cue type, an individual difference factor (i.e., moderator), and their interactions, as well as a random effect of session. Moderators were cue responder status (responder vs. nonresponder), continuous abstinence quit status (quit vs. not quit), dependence level (cigarettes per day and Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence [FTND] score), and gender.

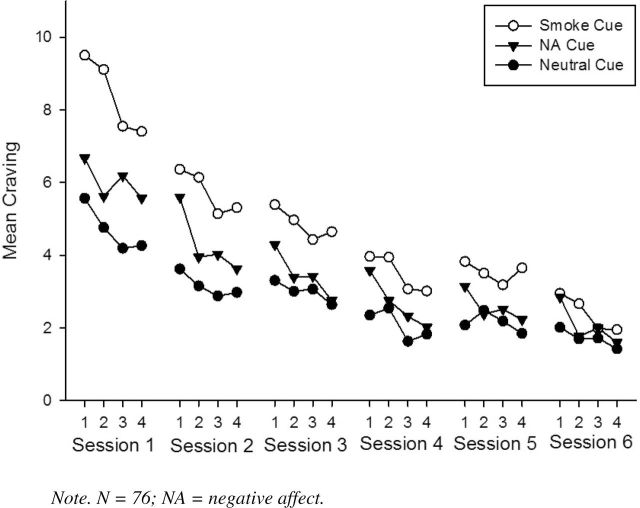

Cue-Provoked Craving Responses

Significant main effects were found for session [F(5, 115) = 22.57], set [F(3, 2236) = 23.01], and cue type [F(2, 3336) = 269.99], all ps < .001. In addition, there were significant set × cue type [F(6, 3245) = 4.85, p < .001] and session × cue type [F(10, 3334) = 14.12, p < .001] interactions, indicating that reduction in craving occurred within- and across-extinction sessions. The set × session × cue type interaction was not significant [F(30, 3243) = .881, p = .65]. Figure 1 shows the craving responses to the three cue types across six sessions and four within-session sets. As seen in the figure and Table 2, craving ratings were highest for smoking cues, followed by NA cues, and lowest for neutral cues. Furthermore, the set × cue type [smoke vs. neutral: F(3, 1232) = 4.09, p = .007; NA vs. neutral: F(3, 1136) = 10.10, p < .001; smoke vs. NA: F(3, 1176) = 18.91, p < .001] and session × cue type [smoke vs. neutral: F(5, 541) = 7.99, p < .001; NA vs. neutral: F(5, 602) = 2.93, p = .01; smoke vs. NA: F(5, 568) = 6.80, p < .001] interactions were significant for all three pairs of cue types, indicating that the rate of decline in craving both within and between sessions (consistent with extinction without any appreciable spontaneous recovery between sessions) was greatest for smoking cues, followed by NA cues, followed by neutral cues. Notably, pairwise comparison analyses indicated that craving ratings to smoking versus neutral cues no longer differed significantly within each set by Session 6, although a difference remained across sets (see Table 2).

Figure 1.

Cue-provoked craving ratings across six cue exposure treatment sessions as a function of Sessions (1–6), Set (1–4), and cue type.

Table 2.

Marginal M (and SEs) for Craving Ratings Across Six Cue Exposure Treatment Sessions as a Function of Cue Type and Set

| Cue type | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral | SE | NA | SE | Smoking | SE | Pairwise | ||

| Session 1 | Set 1 | 5.57 | 0.72 | 6.68 | 0.72 | 9.51 | 0.72 | A***; B**; C*** |

| Set 2 | 4.76 | 0.71 | 5.63 | 0.70 | 9.11 | 0.70 | A***; B*; C*** | |

| Set 3 | 4.19 | 0.69 | 6.19 | 0.69 | 7.55 | 0.69 | A***; B**; C*** | |

| Set 4 | 4.27 | 0.68 | 5.57 | 0.68 | 7.41 | 0.68 | A***; B***; C*** | |

| Average | 4.70 | 0.65 | 6.02 | 0.65 | 8.39 | 0.65 | A***; B***; C*** | |

| Session 2 | Set 1 | 3.62 | 0.66 | 5.60 | 0.66 | 6.37 | 0.66 | A***; B** |

| Set 2 | 3.16 | 0.65 | 3.95 | 0.65 | 6.14 | 0.65 | A***; C*** | |

| Set 3 | 2.88 | 0.64 | 4.03 | 0.64 | 5.14 | 0.64 | A***; B**; C** | |

| Set 4 | 2.98 | 0.63 | 3.63 | 0.63 | 5.31 | 0.63 | A***; C*** | |

| Average | 3.16 | 0.60 | 4.30 | 0.60 | 5.74 | 0.60 | A***; B***; C*** | |

| Session 3 | Set 1 | 3.31 | 0.62 | 4.29 | 0.62 | 5.39 | 0.62 | A***; B*; C* |

| Set 2 | 3.01 | 0.61 | 3.39 | 0.61 | 4.97 | 0.61 | A***; C*** | |

| Set 3 | 3.07 | 0.61 | 3.43 | 0.61 | 4.44 | 0.61 | A***; C* | |

| Set 4 | 2.64 | 0.60 | 2.75 | 0.60 | 4.65 | 0.60 | A*** C*** | |

| Average | 3.01 | 0.56 | 3.47 | 0.56 | 4.86 | 0.56 | A***; B*; C*** | |

| Session 4 | Set 1 | 2.35 | 0.60 | 3.58 | 0.60 | 3.97 | 0.60 | A***; B** |

| Set 2 | 2.55 | 0.59 | 2.76 | 0.59 | 3.94 | 0.59 | A***; C** | |

| Set 3 | 1.63 | 0.59 | 2.32 | 0.59 | 3.08 | 0.59 | A*** | |

| Set 4 | 1.83 | 0.59 | 2.03 | 0.59 | 3.02 | 0.59 | A**; C* | |

| Average | 2.09 | 0.54 | 2.67 | 0.54 | 3.50 | 0.54 | A***; B**; C*** | |

| Session 5 | Set 1 | 2.08 | 0.60 | 3.15 | 0.60 | 3.83 | 0.60 | A***; B* |

| Set 2 | 2.48 | 0.60 | 2.38 | 0.60 | 3.51 | 0.60 | A*; C* | |

| Set 3 | 2.19 | 0.60 | 2.52 | 0.60 | 3.19 | 0.60 | ||

| Set 4 | 1.85 | 0.60 | 2.23 | 0.60 | 3.65 | 0.60 | A***; C** | |

| Average | 2.15 | 0.53 | 2.57 | 0.53 | 3.54 | 0.53 | A***; C*** | |

| Session 6 | Set 1 | 2.02 | 0.67 | 2.85 | 0.67 | 2.95 | 0.67 | |

| Set 2 | 1.70 | 0.68 | 1.77 | 0.68 | 2.67 | 0.68 | ||

| Set 3 | 1.72 | 0.69 | 2.00 | 0.69 | 1.98 | 0.69 | ||

| Set 4 | 1.42 | 0.70 | 1.60 | 0.70 | 1.95 | 0.70 | ||

| Average | 1.72 | 0.58 | 2.06 | 0.58 | 2.39 | 0.58 | A* | |

Notes. NA = negative affect.

N = 76.

Comparisons: A = neutral vs. smoking; B = neutral vs. NA; C = NA vs. smoking.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Moderation of Craving Reduction

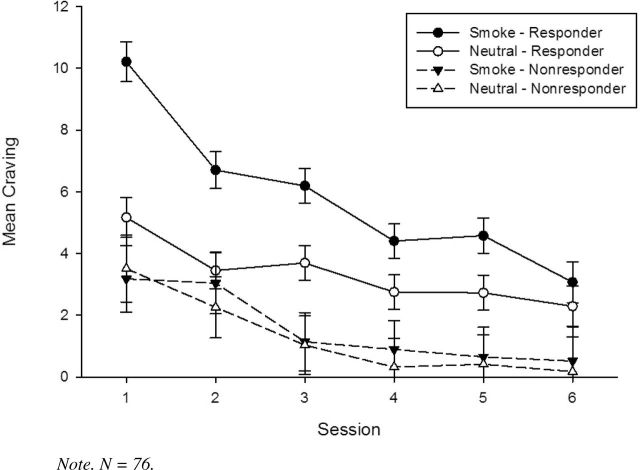

Cue Responders

Previous research indicates that a significant number of substance users (Coffey, Saladin, Libet, Drobes, & Dansky, 1999; Monti et al., 1993) and smokers (Shiffman et al., 2003; Shiffman et al., 2013) do not display differential reactivity to substance cues. Without initial reactivity to smoking cues, nonresponders would not be expected to display declines in craving to such cues, and including them in analyses may diminish the overall extinction effects. Therefore, we examined whether cue responder status moderated the rate of reduction of craving ratings. As expected for smoking cue-provoked craving, there was a main effect for responder status [F(1, 98) = 11.45, p = .001], and a responder × cue interaction [F(1, 805) = 95.12, p < .001], with responders showing greater reactivity to smoking cues relative to neutral cues across all sessions as compared to nonresponders (see Figure 2). Importantly, there was a significant responder status × session × cue type interaction [F(5, 1072) = 10.55, p < .001], such that diminished craving to smoking cues relative to neutral cues across sessions was observed only among cue responders. A similar pattern of moderation by responder status was observed for NA cue-provoked craving ratings (all ps < .01).

Figure 2.

Cue-provoked craving ratings across six cue exposure treatment sessions as a function of session, cue type, and responder status (with SEs).

Quit Status

Next, we examined the effect of quit status on declines in craving. Because smoking between CET sessions (i.e., additional conditioning trials) could hinder extinction, we hypothesized that participants who quit smoking would demonstrate greater declines in craving relative to those who did not quit. Results indicated that participants who quit smoking had lower smoking cue reactivity than those who did not quit [F(1, 780) = 26.10, p < .001]. Craving ratings diminished across sessions [F(5, 281) = 19.06, p < .001], but the rate of decline did not differ by quit status [F(5, 281) = 0.99, p = .42]. Moreover, quit status did not interact with session and cue type [F(5, 1044) = 0.50, p = .78], indicating no differential effect of quit status on craving reduction to smoking cues. A similar pattern was also observed for NA cue-provoked craving ratings.

We also tested whether quit rate was associated with cue responder status. Although cue responders had lower quit rates (61%) than nonresponders (80%), this difference did not reach statistical significance (X 2 [N = 76] = 2.44, p = .12).

Other Potential Moderators

In light of previous research on nicotine dependence and cue reactivity (Payne et al., 1996), as well as gender and cue reactivity (Saladin et al., 2012), we tested cigarettes per day, FTND, and gender as potential moderators of cue-reactivity reduction. No moderation effects emerged for cigarettes per day [smoking cues: F(5, 1044) = 1.26, p = .28; NA cues: F(5, 1141) = 0.33, p = .90] or FTND [smoking cues: F(5, 1043) = 0.79, p = .55; NA cues: F(5, 1139) = 0.11, p = .99]. Gender did not moderate reductions to smoking cues [F(5, 1046) = 1.33, p = .25], but did for NA cues [F(5, 1128) = 2.35, p = .04]. Males showed more rapid reductions in NA cue-provoked cravings; however, both genders had negligible cue reactivity by the final session.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine declines in cue-provoked craving across multiple CET sessions in treatment-seeking smokers. Specifically, we explored within- and between-session declines in cue-provoked craving using a cue-reactivity paradigm. This study also examined the influence of individual difference factors on craving reduction. Results demonstrated a progressive decline in cue-provoked craving across six CET sessions and within the sessions. These findings are consistent with the premise that CET can produce extinction of laboratory cue-provoked cravings to smoking cues. The use of treatment-seeking smokers who attempted to quit smoking prior to initiating CET extends the external validity of earlier research on the reduction of craving to smoking cues (Collins et al., 2011; Corty & McFall, 1984; Miranda et al., 2008).

These findings provide information regarding the pattern of decline in craving over extended exposure trials. Interestingly, cue reactivity continued to decline across all sessions, with the within-set difference in craving between smoking-related and neutral cues falling below statistical significance only at the sixth session. These data suggest that although reduction in craving may be observed from the first cue exposure session, multiple sessions may be necessary to reach sufficient craving reduction such that differential reactivity to smoking-related versus neural cues is no longer evident.

NA cues provoked significant initial cue reactivity, although weaker than that provoked by proximal smoking cues. Moreover, the NA cues evidenced decline in cravings both within and between sessions, when compared to neutral cues. These results are consistent with NA cues serving as distal cues to smoke (Conklin, Robin, Perkins, Salkeld, & McClernon, 2008), and together with evidence that NA is a prime motivator of smoking and smoking relapse (Baker et al., 2004; Brandon et al., 1990; Heckman et al., 2013; Shiffman et al., 1996; Stasiewicz & Maisto, 1993), these results provide support for the inclusion of such stimuli in cue exposure therapies.

Examination of individual differences in this sample allowed us to test important factors that may moderate craving reduction. For instance, as observed in previous research, a significant number of smokers do not display differential reactivity to smoking cues (Shiffman et al., 2003; Shiffman et al., 2013), and hence are not able to demonstrate decline in cue-provoked craving. In this study, 26% of the sample met the “nonresponder” criterion. This phenomenon may be exacerbated among smokers actively engaged in a quit attempt; we observed several participants who reported that acknowledging postcessation cue-provoked craving would be a sign of weakness. As noted by Shiffman et al. (2013), cues obviously intended to provoke craving may elicit efforts to suppress craving in some individuals.

Conditioning theory suggests that smoking between CET sessions constitutes reinstatement episodes (Rescorla & Heth, 1975), which can impede the progress of extinction. Many smokers have sporadic lapses after quitting, but to date, the impact of cessation status on extinction has not been assessed. Findings from this study showed that individuals who were abstinent throughout CET reported lower cue-provoked cravings across all sessions compared to those who continued to smoke, but quit status was not related to the rate of decline in craving. Although this finding appears incompatible with conditioning theory and warrants further research, the lack of difference in the rate of craving reduction (between the “quit” and “not quit”) might be attributed to the very low frequency and quantity of smoking among the majority of those who did not achieve complete abstinence.

Taken together, these individual difference findings suggest the need to identify smoking cue nonresponders in cue-reactivity research and CET paradigms. Nonresponders may not be appropriate for CET, or they may require alternative or more salient stimuli. Additionally, findings support the importance of maintaining smoking abstinence between sessions in order to lower cue-provoked cravings.

Limitations and Future Directions

The cue-reactivity patterns observed in this study are consistent with temporal patterns that would be predicted based on classical conditioning and extinction theory. However, because the study was not designed to test extinction per se (but rather as a treatment study), we did not include an assessment-only control group. Such a condition could control for alternative explanations for the pattern of declining reactivity over time. For example, alternative causes of an apparent extinction effect could include: cessation alone, the passage of time alone, fatigue, demand effects, or the use of NRT. Of these possibilities, cessation alone appears least likely because previous research has found the opposite, the incubation of drug craving, such that cue-provoked craving increases during the early weeks of tobacco abstinence (Bedi et al., 2011). Similar findings have been reported among cocaine addicts and in animal models across a range of substances (see Pickens et al., 2011). It also seems unlikely that the passage of time alone could account for reduced cue-provoked craving in the absence of extinction. Fatigue and demand effects cannot be ruled out; however, the consistent pattern of both within- and between-session reductions in craving may attenuate those concerns. Finally, although previous studies have shown that transdermal NRT does not impede cue reactivity in the short term (e.g., Tiffany et al., 2000, Waters et al., 2004), its influence on cue reactivity over multiple days has not been documented.

Another limitation is that this was an intensive and taxing 4-week treatment, comprising multiple counseling and extinction sessions, NRT, and research-based assessments, which likely contributed to the high attrition rate. Although multiple sessions may be necessary to achieve a therapeutic effect, we will need to reduce the overall client burden in future iterations of the intervention in order to increase its feasibility and implementation potential.

The next steps in the current line of research are to test whether the magnitude of diminished craving predicts smoking relapse and to further test whether advances in CET techniques can enhance long-term treatment outcomes. Some have argued that the limited CET efficacy in the treatment of addictive disorders may be attributed to poor contextual generalization of extinction (Bouton & Bolles, 1985; Collins & Brandon, 2002). Recent research has shifted toward identifying ways to improve CET (Conklin, 2006; Havermans & Jansen, 2003; Lee et al., 2004). In fact, the major goal of the parent study was to test whether the use of an extinction cue would improve extinction generalizability across contexts, which may be critically important for clinical efficacy of CET (Brooks & Bouton, 1994). Similarly, research is needed to test the potential benefits of conducting CET in more naturalistic contexts (i.e., in each patient’s own smoking environments). Another challenge has been the lack of standardized methods for conducting CET. One key example is the role of NRT in CET. Although we attempted to use a delivery modality (transdermal patch) and dosage that were expected to promote smoking cessation without eliminating initial cue reactivity (a pre-condition for extinction), the optimal NRT administration for achieving this balance is not known. Data from this study shed light on some of the specific treatment parameters that need to be considered in designing and implementing cue exposure studies and interventions. Namely, the frequency and number of CET sessions necessary to produce craving reduction and whether the smoker is a cue responder. These methodological and individual factors may be particularly important for guiding the development of efficacious cue exposure interventions.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the American Cancer Society (RSGPB CPPB-109035 to THB).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank K. M. Sismilich for her work as project coordinator, and Raymond Niaura, PhD, and Mark Bouton, PhD, for their consultation on the parent study. The authors also thank Novartis Consumer Health for donating the nicotine transdermal patches.

REFERENCES

- Baker T. B., Brandon T. H., Chassin L. (2004). Motivational influences on cigarette smoking. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 463–491. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. B., Piper M. E., McCarthy D. E., Majeskie M. R., Fiore M. C. (2004). Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review, 111, 33–51. 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi G., Preston K. L., Epstein D. H., Heishman S. J., Marrone G. F., Shaham Y., de Wit H. (2011). Incubation of cue-induced cigarette craving during abstinence in human smokers. Biological Psychiatry, 69, 708–711. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M. E., Bolles R. C. (1985). Contexts, event-memories, and extinction. In Balsam P. D., Tomie A. (Eds.), Context and learning (pp. 133–166). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon T. H., Copeland A. L., Saper Z. L. (1995). Programmed therapeutic messages as a smoking treatment adjunct: Reducing the impact of negative affect. Health Psychology, 14, 41–47. 10.1037//0278-6133.14.1.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon T. H., Herzog T. A., Juliano L. M., Irvin J. E., Lazev A. B., Simmons V. N. (2003). Pretreatment task persistence predicts smoking cessation outcome. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 448–456. 10.1037/0021-843X.112.3.448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon T. H., Tiffany S. T., Obremski K. M., Baker T. B. (1990). Postcessation cigarette use: The process of relapse. Addictive Behaviors, 15, 105–114. 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90013-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon T. H., Vidrine J. I., Litvin E. B. (2007). Relapse and relapse prevention. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 257–284. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon T. H., Zelman D. C., Baker T. B. (1987). Effects of maintenance sessions on smoking relapse: Delaying the inevitable? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 780–782. 10.1037//0022-006X.55.5.780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody A. L., Mandelkern M. A., London E. D., Childress A. R., Lee G. S., Bota R. G. … Jarvik M. E. (2002). Brain metabolic changes during cigarette craving. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 1162–1172. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D. C., Bouton M. E. (1994). A retrieval cue for extinction attenuates response recovery (renewal) caused by a return to the conditioning context. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Processes, 20, 366–379. 10.1037//0097-7403.20.4.366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B. L., Robinson J. D., Lam C. Y., Wetter D. W., Tsan J. Y., Day S. X., Cinciripini P. M. (2006). A psychometric evaluation of cigarette stimuli used in a cue reactivity study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 8, 361–369. 10.1080/14622200600670215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B. L., Tiffany S. T. (1999). Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction, 94, 327–340. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9433273.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Study of Emotion and Attention. (1995). The International Affective Picture System [photographic slides]. Gainesville, FL: The Center for Research in Psychophysiology, University of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Childress A. R., McLellan A. T., O’Brien C. P. (1986). Abstinent opiate abusers exhibit conditioned craving, conditioned withdrawal and reductions in both through extinction. British Journal of Addiction, 81, 655–660. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1986.tb00385.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey S. F., Saladin M. E., Libet J. M., Drobes D. J., Dansky B. S. (1999). Differential urge and salivary responsivity to alcohol cues in alcohol-dependent patients: A comparison of traditional and stringent classification approaches. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 7, 464–472. 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins B. N., Brandon T. H. (2002). Effects of extinction context and retrieval cues on alcohol cue reactivity among nonalcoholic drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 390–397. 10.1037//0022-006X.70.2.390 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins B. N., Nair U. S., Komaroff E. (2011). Smoking cue reactivity across massed extinction trials: Negative affect and gender effects. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 308–314. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin C. A. (2006). Environments as cues to smoke: Implications for human extinction-based research and treatment. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 14, 12–19. 2006-02423-002 [pii] 10.1037/1064-1297.14.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin C. A., Perkins K. A. (2005). Subjective and reinforcing effects of smoking during negative mood induction. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 153–164. 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin C. A., Robin N., Perkins K. A., Salkeld R. P., McClernon F. J. (2008). Proximal versus distal cues to smoke: The effects of environments on smokers’ cue- reactivity. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16, 207–214. 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin C. A., Tiffany S. T. (2002). Applying extinction research and theory to cue-exposure addiction treatments. Addiction, 97, 155–167. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002. 00014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corty E., McFall R. M. (1984). Response prevention in the treatment of cigarette smoking. Addictive Behaviors, 9, 405–408. 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90042-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditre J. W., Oliver J. A., Myrick H., Henderson S., Saladin M. E., Drobes D. J. (2012). Effects of divalproex on smoking cue reactivity and cessation outcomes among smokers achieving initial abstinence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20, 293–301. 10.1037/a0027789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond D. C., Glautier S. (1994). A controlled trial of cue exposure treatment in alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 809–817. 10.1037//0022-006X.62.4.809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson S. G., Shiffman S. (2009). The relevance and treatment of cue-induced cravings in tobacco dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36, 235–243. 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. C., Jaén C. R., Baker T. B., Bailey W. C., Benowitz N. L., Curry S. J. … Wewers M. E. (2008). Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Foltin R. W., Haney M. (2000). Conditioned effects of environmental stimuli paired with smoked cocaine in humans. Psychopharmacology, 149, 24–33. 10.1007/s002139900340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert D. G., Rabinovitch N. E. (1998). International smoking image series with neutral counterparts. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. [Google Scholar]

- Götestam K. G., Melin L. (1983). An experimental study of covert extinction on smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors, 8, 27–31. 10.1016/0306-4603(83)90052–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havermans R. C., Jansen A. T. (2003). Increasing the efficacy of cue exposure treatment in preventing relapse of addictive behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 28, 989–994. 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00289-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T. F., Kozlowski L. T., Frecker R. C., Fagerström K.-O. (1991). The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86, 1119–1127. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman B. W., Kovacs M., Marquinez N., Meltzer L., Tsambarlis M., Drobes D. J., Brandon T. H. (2013). Influence of affective manipulations on smoking motivation: A meta-analysis. Addiction. 10.1111/add.12284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Juliano L. M., Brandon T. H. (1998). Reactivity to instructed smoking availability and environmental cues: Evidence with urge and reaction time. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 6, 45–53. 10.1037//1064-1297.6.1.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj S. K., Joye A., Das R. K., Gibson A. J., Morgan C. J., Curran H. V. (2012). Cue exposure and response prevention with heavy smokers: A laboratory-based randomised placebo-controlled trial examining the effects of D-cycloserine on cue reactivity and attentional bias. Psychopharmacology, 221, 273–284. 10.1007/s00213-011-2571-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski L. T., Pillitteri J. L., Sweeney C. T., Whitfield K. E. (1996). Asking questions about urges or cravings for cigarettes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 10, 248–260. 10.1037//0893-164X.10.4.248 [Google Scholar]

- LaRowe S. D., Saladin M. E., Carpenter M. J., Upadhyaya H. P. (2007). Reactivity to nicotine cues over repeated cue reactivity sessions. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 2888–2899. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazev A. B., Herzog T. A., Brandon T. H. (1999). Classical conditions of environmental cues to cigarette smoking. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 7, 56–63. 10.1037//1064-1297.7.1.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Lim Y., Graham S. J., Kim G., Wiederhold B. K., Wiederhold M. D. … Kim S. I. (2004). Nicotine craving and cue exposure therapy by using virtual environments. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7, 705–713. 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R., Jr, Rohsenow D. J., Monti P. M., Tidey J., Ray L. (2008). Effects of repeated days of smoking cue exposure on urge to smoke and physiological reactivity. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 347–353. S0306-4603(07)00258-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti P. M., Rohsenow D. J. (1999). Coping-skills training and cue-exposure therapy in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol Research & Health, 23, 107–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti P. M., Rohsenow D. J., Rubonis A. V., Niaura R. S., Sirota A. D., Colby S. M., Abrams D. B. (1993). Alcohol cue reactivity: Effects of detoxification and extended exposure. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 54, 235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaura R., Abrams D. B., Shadel W. G., Rohsenow D. J., Monti P. M., Sirota A. D. (1999). Cue exposure treatment for smoking relapse prevention: A controlled clinical trial. Addiction, 94, 685–695. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.9456856.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Anrep G. V. (Ed.). London: Oxford University Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne T. J., Schare M. L., Levis D. J., Colletti G. (1991). Exposure to smoking-relevant cues: Effects on desire to smoke and topographical components of smoking behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 16, 467–479. 10.1016/0306-4603(91)90054-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins K. A. (2009). Does smoking cue-induced craving tell us anything important about nicotine dependence? Addiction, 104, 1610–1616. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins K. A. (2012). Subjective reactivity to smoking cues as a predictor of quitting success. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 14, 383–387. 10.1093/ntr/ntr229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens C. L., Airavaara M., Theberge F., Fanous S., Hope B. T., Shaham Y. (2011). Neurobiology of the incubation of drug craving. Trends in Neurosciences, 34, 411–420. 10.1016/j.tins.2011.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin H., Hodgson R., Stockwell T. (1983). Cue exposure and response prevention with alcoholics: A controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21, 435–446. 10.1016/0005-7967(83)90013-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla R. A., Heth C. D. (1975). Reinstatement of fear to an extinguished conditioned stimulus. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Animal Behavior Processes, 1, 88–96. 10.1037//0097-7403.1.1.88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin M. E., Gray K. M., Carpenter M. J., LaRowe S. D., DeSantis S. M., Upadhyaya H. P. (2012). Gender differences in craving and cue reactivity to smoking and negative affect/stress cues. American Journal on Addiction, 21, 210–220. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00232.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel W. G., Martino S. C., Setodji C., Cervone D., Witkiewitz K., Beckjord E. B. … Shih R. (2011). Lapse-induced surges in craving influence relapse in adult smokers: An experimental investigation. Health Psychology, 30, 588–596. 10.1037/a0023445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Dunbar M., Kirchner T., Li X., Tindle H., Anderson S., Scholl S. (2013). Smoker reactivity to cues: Effects on craving and on smoking behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 264–280. 10.1037/a0028339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Dunbar M. S., Kirchner T. R., Li X., Tindle H. A., Anderson S. J. … Ferguson S. G. (2012). Cue reactivity in non-daily smokers: Effects on craving and on smoking behavior. Psychopharmacology, 226, 321–333. 10.1007/s00213-012-2909-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Engberg J. B., Paty J. A., Perz W. G., Gnys M., Kassel J. D., Hickcox M. (1997). A day at a time: Predicting smoking lapse from daily urge. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 104–116. 10.1037//0021- 843X.106.1.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Hickcox M., Paty J. A., Gnys M., Kassel J. D., Richards T. J. (1996). Progression from a smoking lapse to relapse: Prediction from abstinence violation effects, nicotine dependence, and lapse characteristics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 993–1002. 10.1037/0022-006X.64.5.993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Shadel W. G., Niaura R., Khayrallah M. A., Jorenby D. E., Ryan C. F., Ferguson C. L. (2003). Efficacy of acute administration of nicotine gum in relief of cue-provoked cigarette craving. Psychopharmacology, 166, 343–350. 10.1007/s00213-002-1338-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz P. R., Brandon T. H., Bradizza C. M. (2007). Effects of extinction context and retrieval cues on renewal of alcohol-cue reactivity among alcohol-dependent outpatients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 21, 244–248. 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz P. R., Gulliver S. B., Bradizza C. M., Rohsenow D. J., Torrisi R., Monti P. M. (1997). Exposure to negative emotional cues and alcohol cue reactivity with alcoholics: A preliminary investigation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 1143–1149. 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00047-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz P. R., Maisto S. A. (1993). Two-factor avoidance theory: The role of negative affect in the maintenance of substance use and substance use disorder. Behavior Therapy, 24: 337–356. 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80210–2 [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke W. G., Breiner M. J., Curtin J. J., Lang A. R. (2004). Assessment of substance cue reactivity: Advances in reliability, specificity, and validity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 148–159. 10.1037/0893-164X. 18.2.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ternes J. W., O’Brien C. P., Testa T. T. (1982). Rapid acquisition of conditioned responses to hydromorphone in detoxified heroin addicts. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 18, 215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany S. T., Cox L. S., Elash C. A. (2000). Effects of transdermal nicotine patches on abstinence-induced and cue-elicited craving in cigarette smokers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 233–240. 10.1037//0022-006X.68.2.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany S. T., Warthen M. W., Goedeker K. C. (2009). The functional significance of craving in nicotine dependence. In Bevins R. A., Caggiula A. R. (Eds.), The motivational impact of nicotine and its role in tobacco use (pp. 171–197). New York, NY: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany S. T., Wray J. (2009). The continuing conundrum of craving. Addiction, 104, 1618–1619. 10.1111/j.1360- 0443.2009.02588.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany S. T., Wray J. M. (2012). The clinical significance of drug craving. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1248, 1–17. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06298.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinci C., Copeland A. L., Carrigan M. H. (2012). Exposure to negative affect cues and urge to smoke. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20, 47–55. 10.1037/a0025267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters A. J., Shiffman S., Sayette M. A., Paty J. A., Gwaltney C. J., Balabanis M. H. (2004). Cue-provoked craving and nicotine replacement therapy in smoking cessation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 1136–1143. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray J. M., Gass J. C., Tiffany S. T. (2013). A systematic review of the relationship between craving and smoking cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15, 1167–1182. 10.1093/ntr/nts268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelman D. C., Brandon T. H., Jorenby D. E., Baker T. B. (1992). Measures of affect and nicotine dependence predict differential response to smoking cessation treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 943–952. 10.1037//0022-006X.60.6.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]