Myotonic dystrophy (DM) is a chronic, slowly progressing, highly variable, inherited multisystemic disease, which includes two main types: DM type 1 (DM1) and DM type 2 (DM2). Both DM1 and DM2 are autosomal dominantly inherited disorder. DM1, also called Steinert disease, is characterized by myotonia, muscle weakness, muscular dystrophy, endocrinopathy, cataract, cardiac conduction defect, central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, and so on. The symptoms of CNS abnormalities mainly include impaired motor function, cognitive impairment, fatigue, and depression. The magnetic resonance images (MRI) of the brain may show brain atrophy and (or) white matter hyperintense lesions (WMHLs) on T2 or fluid-attenuated inversion recovery.[1] DM1 is caused by an expanded (CTG) n repeat (from 37 to several thousands) within the noncoding 3’untranslated region of the myotonic dystrophy protein kinase (DMPK) gene on chromosome 19q35. DM2, also called proximal myotonic myopathy, is rarer than DM1 and generally manifests with milder signs and symptoms, and is caused by an expanded CCTG repeat (from 75 to 11,000 repeats) in the first intron of the zinc finger protein 9 (ZNF9) gene on chromosome 3q21. Till now, there are few reports of DM with WMHLs in China. Here, we reported one case of DM1 with WMHLs, characterized by bilateral anterior temporal WMHLs (ATWMHLs).

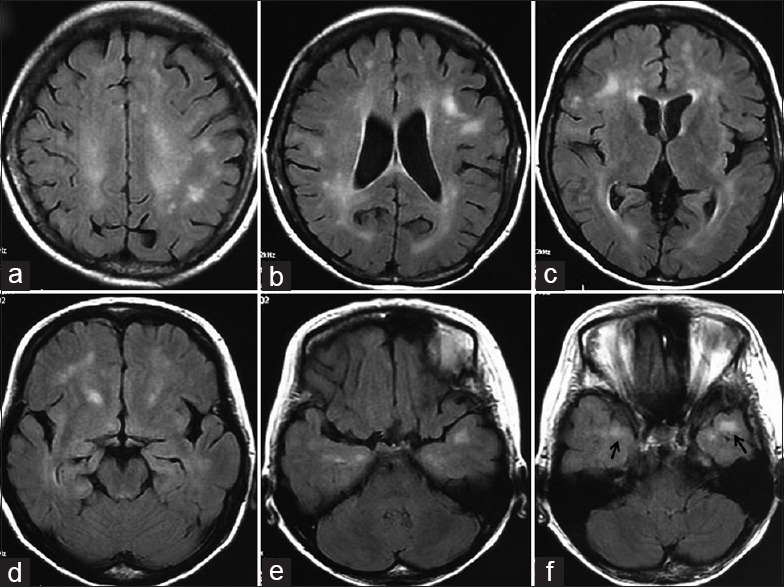

A 50-year-old woman presented to Department of Neurology, China-Japan Friendship Hospital on April 21, 2014, because of fatigue and daytime sleepiness for 3 months. She did not have dizziness, limb weakness or movement disorder. But recently, she was depressed in life and unwilling to communicate with people or go to work. She suffered bilateral cataracts 7 years ago and had already done the surgery. She had no history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, migraine, and stroke. Physical examination only found she had no tendon reflexes in the extremities. The brain MRI showed extensive WMHLs, subcortical or periventricular and bilateral ATWMHLs [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The axial brain magnetic resonance images (fluid attenuated inversion recovery) of this 50-year-old female patient with myotonic dystrophy type 1. (a-d) White matter hyperintense lesions (WMHLs) were bilaterally detected in both subcortical and periventricular areas, single or confluent and were asymmetric in appearance; (e-f) Areas of high signal in the subcortical white matter of the anterior temporal lobes (anterior temporal WMHLs) (arrows).

After admission, we knew she began to lose hair 5 years ago and had a family history of cataract and baldness. The further examination showed baldness, ax-shaped face, and myotonia. Routine blood test, blood glucose, liver and renal function, cardiac enzymes, antinuclear antibody, double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, thyroid function, thyroid−associated antibodies, and hormone levels were normal. Echocardiography was normal, but electrocardiogram revealed PR interval prolongation. She scored 30 points in minimum mental state examination and 29 points in Montreal Cognitive Assessment with 1 loss in repeat. Electromyography showed myotonia discharge. The family history included that her 23-year-old son was suspected as “muscular dystrophy” at age of 8 years for his muscle weakness, but without confirmed diagnosis. He was bedridden and could only move his fingers years ago.

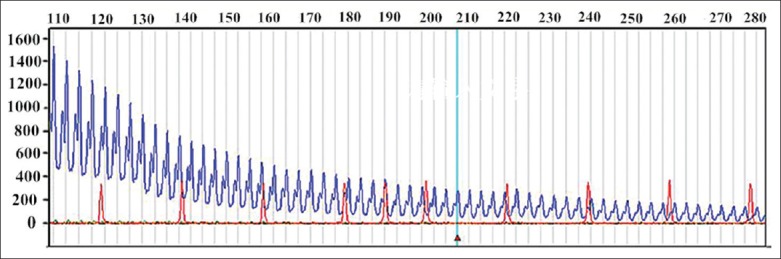

According to the main clinical presentation and the results of the brain MRI, the relevant differential diagnoses of WMHLs were be considered at first. The features of the MRI were extensive and bilateral cerebral hemisphere WMHLs, especially bilateral ATWMHLs which were strong suggestive to subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy autosomal dominant cerebral artery disease (CADASIL), and some types of autoimmune diseases like Hashimoto encephalopathy. But this patient had no history of migraine, recurrent ischemic stroke, and no similar family history. All of his autoantibodies including thyroid–associated antibodies were normal. Although the patient herself showed no significant muscle weakness, her son had a suspected muscular dystrophy. She had a history and family history of early-onset bilateral cataracts and hair loss. Then we considered the diagnosis of DM and noticed she also had baldness, ax-shaped face, and myotonia, which were in support of DM. In order to confirm the diagnosis, the genetic testing was performed after the informed consent was obtained from the patient. The blood (3 ml) was drawn for the gene test. Genomic DNA was isolated from blood leukocytes using standard protocols. The CTG repeats in the 3’-untranslated region of DPMK gene were detected by tri-primer polymerase chain reaction (TP−PCR) and capillary electrophoresis using standard methods. The genetic testing showed that the number of her CTG repeats was more than 50 times [Figure 2], which confirmed the diagnosis of DM1.

Figure 2.

The number of CTG repeats of myotonic dystrophy protein kinase gene is more than 50 times using capillary electrophoresis (the blue line shows the number is 50 times).

The clinical manifestations of DM1 are characterized by myotonia, muscle weakness, and muscular dystrophy. Recent studies have demonstrated that the degree of myopathy, disease severity and age of onset might be correlated with the number of triplet repeats in DM patients, and it has the phenomenon of genetic anticipation.[2] As to this patient, the age of onset was late, and she had mild muscular abnormalities, which might be related to small number repeats. The patient's son had an early onset and the symptoms were serious probably due to this genetic anticipation, her son. But, unfortunately, the patient's son refused to perform the genetic testing, we could not confirmed this hypothesis.

In addition to muscular abnormalities, DM1 is a multi-systemic disease, frequently involving ocular, gonadal, cardiac, endocrine system, and CNS. The most important feature of this patient was that she had an obvious involvement of other systems outside muscular system. The first symptom was early-onset cataract, and the reason she came to us was fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and depression. Cataract is the main ocular symptoms in DM1 patients. The prevalence rate is up to 67.0%, of which 64.8% is disabling, and the present of cataract has nothing to do with the number of CTG repeats. Selective scanning is necessary for detecting DM patients in its pedigrees. Cataract may become the first and even the only symptom of DM. Medica et al.[3] did genetic testing in 274 early-onset cataract adult patients without signs of DM1 or a family history of DM1, and found 4 cases of completely mutations in DMPK gene. Therefore, patients who have early-onset of cataract should be considered the possible of genetic diseases, like DM1.

There are no specific symptoms of CNS involvement in DM1, and the main presentation is hypersomnia and apathy. With the development of imaging techniques, the CNS damages were gradually revealed. The findings of brain MRI in DM describe a wide variety of abnormalities ranging from WMHLs, ventricular dilatation, and cerebral atrophy. Much of the literatures to this point have focused on WMHLs, and the prevalence of WMHLs in DM is about 78%.[4] However, some have suggested that neuropathological studies may have underestimated the extent of WMHLs and that even “normal-appearing white matter” is disturbed. For example, using magnetization transfer imaging or T2-relaxometry, abnormalities were found in normal-appearing white matter. At autopsy, the abnormalities seen on MRI have been found to correspond to significant neuropathological changes including “severe loss and disordered arrangement of myelin sheaths and axons.” WMHLs are usually diffuse in both hemispheres, subcortical or preventricular, single or confluent, and often asymmetric in appearance. DM2 patients more frequently showed moderate to severe confluent periventricular WMHLs with occipital predilection that differed from predominantly patchy and more widespread foci without a lobe predilection in DM1. ATWMHLs are exclusively seen in DM1 patients and can be used as radiographic makers for DM1.[4] As to our patient, we found WMHLs first, and then we considered the diagnosis of DM. The ATWMHLs prompted it may be DM1. The neuropathological and MRI aspects of temporal WMHLs seemed quite different from lobar WMHLs. The disease duration was positively correlated with the temporal WMHLs, although this correlation was weaker than that with the lobar WMHLs. This finding suggested that temporal WMHLs might develop and progress during the disease at a different rate. The lesions might involve initially the U fibers in the anteromedial portion of temporal poles, and then the U fibers of whole poles and finally the entire polar white matter.

The etiology and pathogenesis of WMHLs in DM are still unknown. There is no relationship between the WMHLs scores and the CTG repeats. Recent advances in molecular genetics in vitro and using mouse models have shed light on the pathogenesis. The expression of the transcribed microsatellites in the 3’-region of the DMPK gene or intron 1 of the ZNF9 gene produces ribonucleoprotein inclusions in the nuclei of muscle fibers and other cells thereby affecting RNA and protein metabolism (trans-effects). Dysregulation of the human brain microtubule-associated tau mRNA maturation was reported in DM1.

The relationship between the degree of cognitive impairment and WMHLs is still controversial. Impaired frontal and temporal lobes functions such as executive and visuospatial functions are predominant neuropsychological findings in DM1, which is in correspondence with the abnormal areas in MRI. Single-photon emission computed tomography or positron emission tomography studies have also demonstrated significantly low cerebral blood flow in both frontal and temporal-parietal regions. WMHLs have been shown to be associated with intellectual dysfunction, psychomotor speed, verbal fluency, attention in some study. However, some authors failed to found an association between the severity of WMHLs and the mental impairment. We must pay more attention to the neuropsychological tests in DM1 patient and MRI should be done if the patient has dysfunctions.

The main presentations of CNS involvement in our patient were fatigue, daytime sleepiness, and depression, which were the most common clinical manifestations in classic DM1. The prevalence of fatigue or daytime sleepiness was 68–70%, and the prevalence of depression was 32–38% in DM1. Weakness of the oropharyngeal and respiratory muscles leading to obstructive sleep apnea and alveolar hypoventilation has been regarded as causative factors of daytime sleepiness. However, there is increasing evidence that tiredness primarily results from CNS dysfunction such as hypocretin neurotransmission system rather than progressive respiratory weakness. More depressive symptoms occur in DM1 patients with less WMHLs, and this result is opposite to DM2, which indicated that depression might be a reactive adjustment disorder rather than a consequence of structural brain damage. In a two-center, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial, a single 20-mg dose of methylphenidate significantly reduced daytime sleepiness in DM1 patients whose Epworth Sleepiness Scale score ≥10.[5]

In summary, our study revealed that we should pay attention to the diagnosis of DM in case of WMHLs, and patients with bilateral anterior temporal lobe involvement may be considered as DM1. Other symptoms such as myotonia, muscle weakness, muscular dystrophy, and cataracts can support this diagnosis. Genetic testing should be done to confirm it. At the same time, in case of DM1 patients, we should do MRI test to find the CNS damages.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Shao Guo

Source of Support: This study was supported by grants from China-Japan Friendship Hospital Youth Science and Technology Excellence Project (No. 2014-QNYC-A-04) and China-Japan Friendship Hospital Scientific Research Project (No. 2013-MS-11).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meola G, Sansone V. Cerebral involvement in myotonic dystrophies. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36:294–306. doi: 10.1002/mus.20800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foff EP, Mahadevan MS. Therapeutics development in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:160–9. doi: 10.1002/mus.22090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medica I, Teran N, Volk M, Pfeifer V, Ladavac E, Peterlin B. Patients with primary cataract as a genetic pool of DMPK protomutation. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:123–8. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornblum C, Reul J, Kress W, Grothe C, Amanatidis N, Klockgether T, et al. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging in genetically proven myotonic dystrophy type 1 and 2. J Neurol. 2004;251:710–4. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puymirat J, Bouchard JP, Mathieu J. Efficacy and tolerability of a 20-mg dose of methylphenidate for the treatment of daytime sleepiness in adult patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1: A 2-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 3-week crossover trial. Clin Ther. 2012;34:1103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2012.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]