Abstract

Kappa opioid receptor (KOR) modulation is a promising target for drug discovery efforts due to KOR involvement in pain, depression, and addiction behaviors. We recently reported a new class of triazole KOR agonists that displays significant bias toward G protein signaling over βarrestin2 recruitment; interestingly, these compounds also induce less activation of ERK1/2 map kinases than the balanced agonist, U69,593. We have identified structure–activity relationships around the triazole scaffold that allows for decreasing the bias for G protein signaling over ERK1/2 activation while maintaining the bias for G protein signaling over βarrestin2 recruitment. The development of novel compounds, with different downstream signaling outcomes, independent of G protein/βarrestin2 bias, provides a more diverse pharmacological toolset for use in defining complex KOR signaling and elucidating the significance of KOR-mediated signaling.

Keywords: Functional selectivity, MAP kinase, biased agonism, G protein coupling, arrestin, GPCR

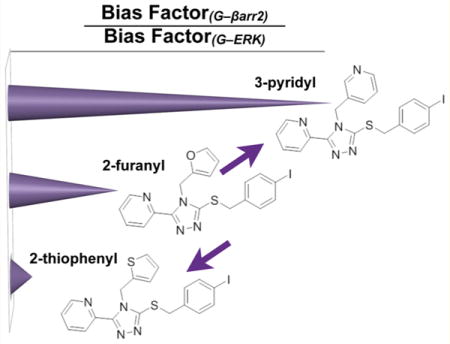

Graphical abstract

Kappa opioid receptor (KOR) signaling is involved in numerous biological processes. KOR agonists produce antinociception without the physical dependence and respiratory failure associated with mu opioid receptor-directed pain therapies.1–4 Additionally, KOR plays a role in dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways in the CNS wherein KOR activation can decrease dopamine levels. When concomitantly administered with drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, KOR agonists can decrease the reinforcing and rewarding effects.5–9 When administered prior to a stress-inducing event, KOR antagonists can prevent the decrease in dopamine that triggers relapse in drug extinction paradigms.10,11 KOR antagonists have been shown to have antidepressant and anxiolytic effects.12–14 These observed behavioral effects suggest KOR modulation is a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of pain, drug addiction, and depression. Additionally, a partial KOR agonist is currently used clinically in the treatment of intractable itch.15–18 However, aversive side effects such as dysphoria, sedation, dissociation, diuresis, and depression all limit the therapeutic potential of KOR agonism.2,3,10,19–22

Currently it is hypothesized that the antinociception associated with KOR agonism results from G protein mediated signaling events while certain negative side effects may result from βarrestin2-mediated signaling events.23 Thus, developing KOR agonists that are biased toward G protein coupling and away from βarrestin2 recruitment will serve as important tools for delineating the contributions of each pathway to the physiological effects of KOR activation.24–28 Recently, we reported on a number of selective KOR agonists of a triazole scaffold that display functional selectivity, or “bias”, toward G protein signaling over βarrestin2 recruitment.29,30

In addition to looking at G protein signaling and βarrestin2 recruitment, ERK1/2 signaling was investigated as ERK activation can occur via G protein-dependent or βarrestin2-dependent signaling pathways.31–35 In the initial series of five triazoles, we noted that, in each case, the profiles for activating ERK1/2 paralleled their profiles for activating βarrestin2 recruitment to KOR. In other words, all of the previously reported triazoles have low potency for activating ERK1/2 although they maintain potency and efficacy in mediating G protein signaling.29 This is very different from 6′GNTI, a previously described G protein/βarrestin2 biased agonist, as 6′GNTI promotes potent ERK1/2 activation in the cell lines that parallels its ability to activate G protein signaling. These observations demonstrate that while two agonists may display bias for G protein signaling over βarrestin2 recruitment, the observed bias is not necessarily predictive of how the agonist will induce downstream signaling to MAP kinases. Herein we evaluate the triazole structure–activity relationship and show that the bias for ERK activation can be altered while preserving βarrestin2 bias with respect to G protein signaling.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The compounds examined in this study were selected based on trends observed in initial screening of compounds developed in iterative rounds of chemistry around the triazole scaffold initially described by Zhou et al. (Figure 1).29 In these three examples, we investigate the contribution of the three substitutions, namely, the furan, thiophene, or pyridine groups, for their impact on proximal G protein signaling and βarrestin2 recruitment as well as upon the downstream activation of ERK1/2. In all studies, test compounds are assayed in parallel with the KOR agonist, U69,593, which serves as the reference agonist in each of the assays.

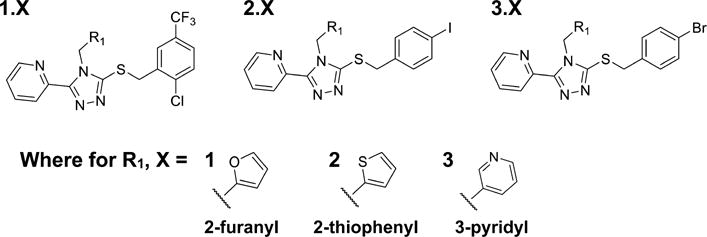

Figure 1.

Structures of KOR agonists. Previous identification of triazole compounds with KOR agonist activity29,30 has led to the synthesis of compounds analyzed here.

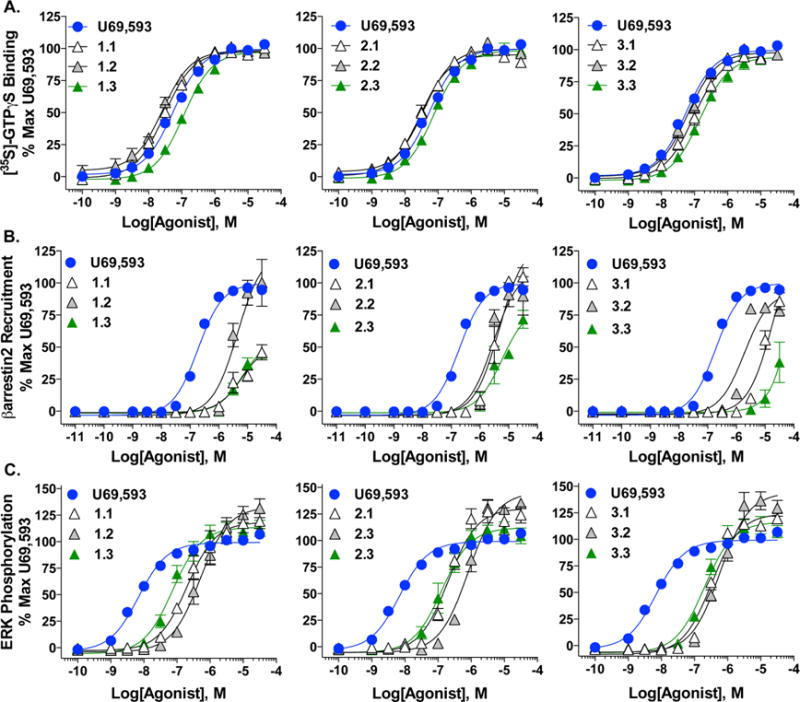

G protein signaling studies were performed in membranes from CHO-K1 cells stably expressing human KOR (CHO-hKOR) as previously described25,29 (Figure 2A, Table 1). All of the triazole compounds display similar potencies to U69,593 ranging from 27 to 149 nM and act as full agonists. In each series, the furan and thiophene analogues (X.1 and X.2, respectively) have similar potencies while the pyridine analogue (X.3) results in a slight but statistically significant decrease in potency relative to either furanyl or thiophenyl substitution.

Figure 2.

Triazole analogues stimulate G protein coupling, βarrestin2 recruitment, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation to different degrees relative to U69,593. G protein coupling (A) identifies triazole analogues as potent, full agonists in the presence of [35S]GTPγS. High content imaging of βarrestin2 (B) illustrates that triazole analogues recruit βarrestin2 only at concentrations significantly higher than U69,593. ERK1/2 phosphorylation (C) measured by fluorescence intensity detection of the ratio of pERK1/2 to tERK1/2 concludes that triazole test compounds exceeds stimulation observed for U69,593. Assays were run with concentrations of indicated agonists and are displayed as percentage of maximal U69,593 stimulation. Calculated potencies and efficacies are presented in Table 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3).

Table 1.

Potencies and Efficacies of Triazole Analogues Compared to U69,593a

| entry | G protein assay

|

βarrestin2 assay

|

ERK1/2 phosphorylation

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nM) | EMAX, % of max U69,593 | EC50 (nM) | EMAX, % of max U69,593 | % U69,593 at 10 μM | EC50 (nM) | EMAX,% of max U69,593 | % U69,593 at 10 μM | |

| U69,593 | 61.2 ± 9.4 | 100 | 194.2 ± 15.6 | 100 | 100 | 7.2 ± 0.9 | 100 | 100 |

| 1.1 | 31.8 ± 6.4e | 98 ± 1 | 8721 ± 2177b | 56 ± 5 | 29 ± 5 | 242.1 ± 46.9bde | 120 ± 10 | 114 ± 7 |

| 1.2 | 27.2 ± 3.5be | 98 ± 1 | 6245 ± 1436b | 147 ± 25 | 94 ± 8 | 593.6 ± 115.2bce | 139 ± 9 | 128 ± 6 |

| 1.3 | 115.3 ± 8.9bcd | 97 ± 1 | 10130 ± 3253b | 65 ± 6 | 38 ± 5 | 107.7 ± 24.5bcd | 114 ± 8 | 107 ± 7 |

| 2.1 | 30.3 ± 4.5be | 95 ± 1 | 13460 ± 8290b | 228 ± 96 | 105 ± 2 | 222.0 ± 22.9bde | 131 ± 10 | 113 ± 8 |

| 2.2 | 40.3 ± 8.5e | 100 ± 1 | 3567 ± 680b | 123 ± 19 | 94 ± 9 | 788.9 ± 159.4bce | 143 ± 4 | 131 ± 4 |

| 2.3 | 75.5 ± 7.1cd | 98 ± 3 | 10 090 ± 2727b | 101 ± 7 | 46 ± 3 | 107.4 ± 18.3bcd | 109 ± 6 | 110 ± 8 |

| 3.1 | 84.7 ± 18.4e | 91 ± 3 | >31 000b | 58 ± 8 | 340.1 ± 25.1bde | 125 ± 2 | 114 ± 4 | |

| 3.2 | 66.6 ± 15.1e | 98 ± 1 | 1941 ± 90.9b | 94 ± 2 | 87 ± 3 | 672.3 ± 112.6bce | 149 ± 13 | 135 ± 8 |

| 3.3 | 149.1 ± 11.5bcd | 94 ± 4 | >31 000b | 10 ± 7 | 227.3 ± 40.1bcd | 117 ± 7 | 112 ± 6 | |

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3).

Student’s t test analysis, U69,593 vs test compound, p < 0.05.

Student’s t test analysis, X.1 vs X.2 or X.3, p < 0.05.

Student’s t test analysis, X.2 vs X.1 or X.3, p < 0.05.

Student’s t test analysis, X.3 vs X.1 or X.2, p < 0.05.

To investigate whether these compounds are biased against βarrestin2 recruitment, they were evaluated for their ability to stimulate βarrestin2 recruitment using automated high content imaging in U2OS cells stably expressing human KOR and GFP-tagged βarrestin2 (U2OS-hKOR-βarr2-GFP) as previously described.29 All of the test compounds are weakly potent (>2 μM EC50) in the βarrestin2 recruitment assay, a log order difference in potency compared to the reference compound, U69,593 (194.2 ± 15.6 nM) (Figure 2B, Table 1). Interestingly, the response does not reach a plateau at the highest concentrations tested for the triazoles, which was also the case for those initially described.29 Since nonlinear regression analysis cannot stringently predict a maximal effect when a plateau is not reached, relative efficacy values are also presented as a percent of 10 μM U69,593 stimulation at 10 μM to facilitate comparisons (Table 1).

ERK1/2 activation was assessed using a multiwell plate immunocytochemistry approach with the CHO-hKOR cell line as previously described.25,29 While none of the analogues are as potent as U69,593 (7.2 ± 0.9 nM) (Figure 2C, Table 1), an interesting structure–activity relationship begins to emerge within each group of the triazole compounds. Specifically, the analogues demonstrate a rank order of potency with substitutions on 4-N of the triazole ring: thiophenyl (X.2) < furanyl (X.1) < pyridinyl (X.3). As with the previously reported triazoles,29 each new triazole analogue tends to produce a greater maximal stimulation of ERK1/2 compared to U69,593.

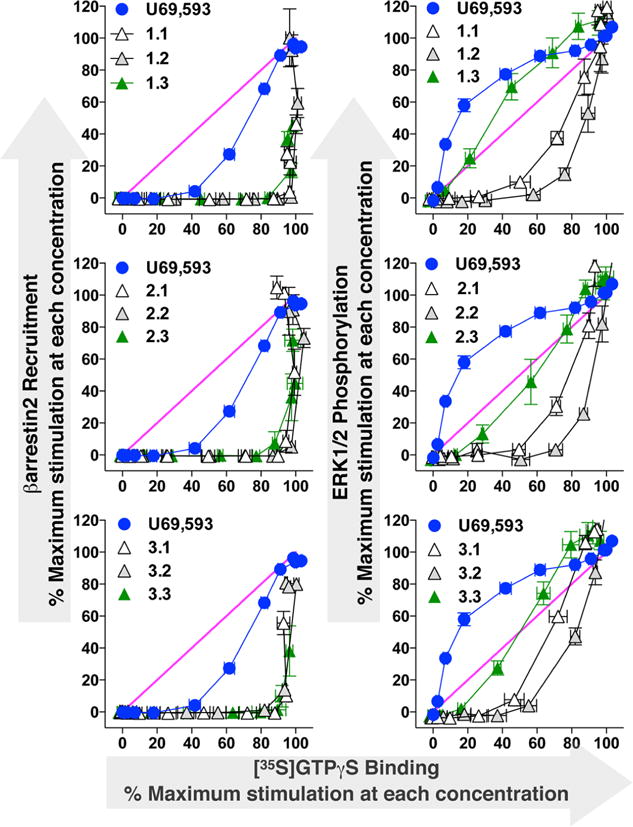

In order to compare the activity of these agonists across multiple signaling platforms, it is necessary to address the system-dependent properties of each response. These can include differences in receptor number and response amplification as well as other properties that are specific to each system. Therefore, we present several different forms of analysis to provide evidence that the SAR trend we observe is the result of a change in the system independent effects of the ligands. In one effort to contrast the changes in ERK phosphorylation by the pyridine analogues (X.3) with the effect of these analogues in βarresin2 recruitment, the percent maximum stimulation at each concentration for [35S]GTPγS binding (abscissa) was graphed versus the percent maximum stimulation at each concentration for βarrestin2 recruitment (ordinate, left) and ERK 1/2 phosphorylation (ordinate, right) (Figure 3). This equimolar graph was originally proposed by Gregory et al.36 In this representation, a compound that produces an equivalently efficacious response in each assay at each dose tested, a linear correlation would be derived (shown in the pink curve for reference). One can readily see that the modifications at the 4-N position of the triazole ring has little effect on modulating βarrestin2 recruitment relative to G protein signaling (all the curves overlap and are rightward of U69,593). When ERK and G protein signaling are compared, the pyridinyl group substitution (X.3) leads to an ERK activation profile that becomes closer to that obtained with U69,593.

Figure 3.

Comparison of G protein signaling to βarrestin2 recruitment and ERK1/2 activation as a function of efficacy at each dose tested. Data are presented as the maximal stimulation at each agonist concentration normalized to U69,593. These equimolar plots present the comparison of each test agonist’s response profile to the stimulation produced by the reference agonist, U69,593. For comparison, each graph also presents an equimolar relationship of unity, slope equal to one. Each test agonist produces stimulation of G protein coupling before measurable βarr2 recruitment is observed. Conversely, the ERK phosphorylation produced by the test agonists is ligand dependent and some analogues approach both the reference agonist and the unity line.

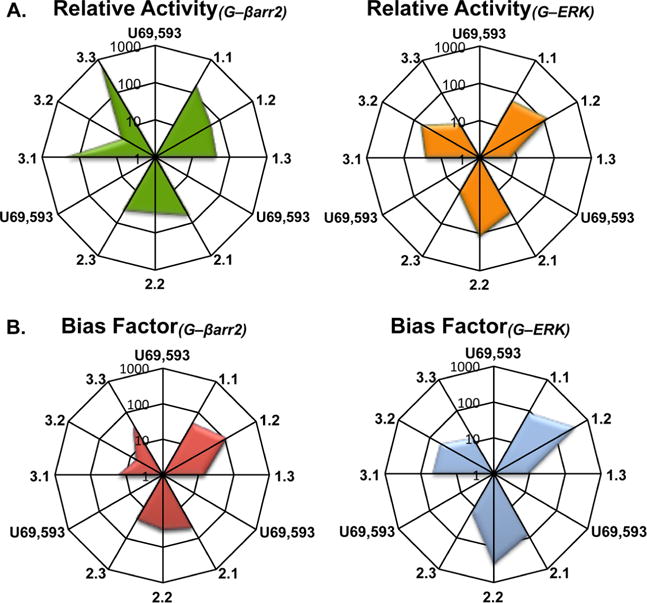

In a second effort to quantitatively assess and compare the potencies in each signaling assay, the relative activity of each test agonist was estimated using the method described by Griffin et al.37 This method incorporates both the potency and maximum response of each test agonist to produce a single value of relative activity that can be compared between responses relative to the performance of a full agonist, the reference agonist (here U69,593) in each system; Figure 4A presents the comparison of the relative activity of each test agonist. While this manner of analysis helps to visualize the empirical relationship of the responses produced by each test agonist, the analysis does not consider inherent differences between the assay systems that are compared.38 Therefore, to gain a more quantitative comparison between compounds, the data in Figure 2 were fit to the operational model to produce estimates of the relative intrinsic activity of each test agonist in each measure of response (Table 2).29,38,39 The derived values, comparing G protein coupling versus βarrestin2 recruitment or ERK1/2 activation, are plotted as “bias factors” in Figure 4B and as ΔΔLogR values including standard error of the mean calculations in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Bias factors (ΔΔLogR values) and relative activity ratios represented. (A) Relative activity of each test agonist (Emax/EC50) is presented relative to the reference agonist U69,593. (B) Bias factors were calculated using the operational model and are presented as the degree of bias toward G protein coupling and away from βarr2 recruitment and toward G protein coupling and away from ERK 1/2 phosphorylation relative to U69,593. The center of each figure presents a value equal to one (as defined by the reference agonist). The bias factor of the reference agonist is equal to one and the values greater than one indicate bias toward G protein coupling compared to βarr2 recruitment or ERK phosphorylation. Values can be found summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameter Estimates and Bias Factors Produced by Fitting to the Operational Modela

| entry | ΔLogR

|

ΔΔLogR(assay1−assay2)

|

bias factor (10ΔΔLogR)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G protein assay | βarrestin2 assay | ERK 1/2 | ΔΔLogR(G−βarr2) | 95% CI | ΔΔLogR(G−ERK) | 95% CI | G/βarr2 | G/ERK | |

| U69,593 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1.1 | 0.28 ± 0.16 | −1.39 ± 0.11 | −1.69 ± 0.26 | 1.7 ± 0.19 | 1.2–2.1 | 2.0 ± 0.19 | 1.5–2.4 | 47 | 93 |

| 1.2 | 0.59 ± 0.12 | −1.50 ± 0.21 | −1.93 ± 0.18 | 1.9 ± 0.21 | 1.6–2.5 | 2.6 ± 0.19 | 2.2–3.1 | 122 | 419 |

| 1.3 | −0.34 ± 0.09 | −1.50 ± 0.15 | −1.29 ± 0.06 | 1.2 ± 0.20 | 0.7–1.6 | 1.0 ± 0.19 | 0.5–1.4 | 15 | 9 |

| 2.1 | 0.30 ± 0.13 | −1.39 ± 0.13 | −1.64 ± 0.10 | 1.7 ± 0.19 | 1.3–2.1 | 1.9 ± 0.19 | 1.5–2.4 | 49 | 88 |

| 2.2 | 0.33 ± 0.19 | −1.19 ± 0.10 | −1.97 ± 0.20 | 1.5 ± 0.19 | 1.1–2.0 | 2.5 ± 0.19 | 1.9–3.0 | 33 | 304 |

| 2.3 | 0.01 ± 0.12 | −1.40 ± 0.20 | −1.21 ± 0.01 | 1.4 ± 0.22 | 0.9–1.9 | 1.2 ± 0.22 | 0.7–1.7 | 25 | 16 |

| 3.1 | −0.34 ± 0.16 | −1.58 ± 0.11 | −1.93 ± 0.09 | 1.2 ± 0.20 | 0.8–1.7 | 1.7 ± 0.20 | 1.2–2.1 | 17 | 47 |

| 3.2 | −0.24 ± 0.17 | −1.09 ± 0.09 | −1.82 ± 0.10 | 0.9 ± 0.22 | 0.4–1.3 | 1.7 ± 0.22 | 1.2–2.2 | 7 | 46 |

| 3.3 | −0.55 ± 0.14 | −2.12 ± 0.16 | −1.63 ± 0.06 | 1.6 ± 0.22 | 1.1–2.1 | 1.1 ± 0.19 | 0.7–1.6 | 37 | 14 |

The parameter estimates are presented as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3). The ΔΔLogR for each bias calculation is presented ± SEM (n ≥ 3) along with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Bias factor is calculated as the antilog of the ΔΔLogR for each response pair.

For both the G protein coupling and βarrestin2 recruitment data, the fit of the model provided straightforward parameter estimates for each agonist (ΔLogR; Table 2). When considering the preference for G protein signaling over βarrestin2 recruitment (ΔΔLogRG−βarr2), substitutions at the 4-N position on the triazole ring have no conserved effect of either increasing or decreasing the degree of bias seen when comparing compound performance in these assays. However, comparison of the X.1, X.2, and X.3 substitutions at this position produce a conserved change in bias factors when comparing G protein signaling and ERK1/2 activation (ΔΔLogRG−ERK, Figure 4B, Table 2). For each scaffold, the thiophene (X.2) substitution produces a greater bias factor for G protein signaling over ERK1/2 activation while the pyridine (X.3) substitution produces a smaller bias factor when compared to the furan (X.1) substitution. In Table 2, standard error of the mean values and 95% confidence intervals are presented to suggest that these differences may prove to be statistically significant; however, the rigor of statistics for propagating error of comparison over multiple populations has not been applied.

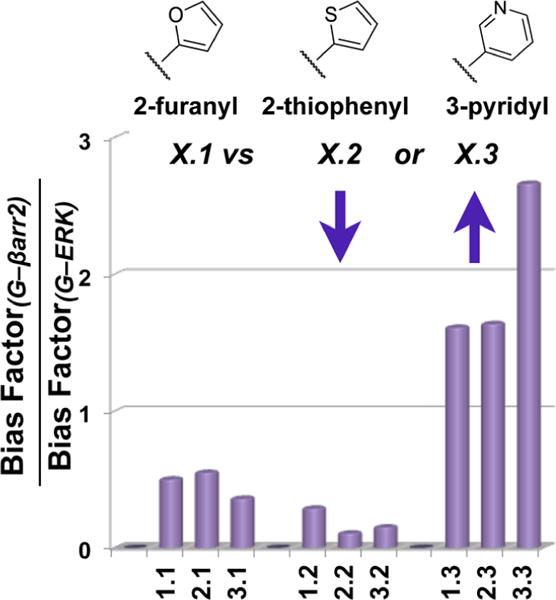

The results of all of these forms of analysis lead us to conclude that the incorporation of a basic nitrogen atom in one of the heterocycles attached to the triazole does not lead to a universal trend for altering bias toward G protein coupling compared to βarrestin2 recruitment. However, a conserved trend becomes apparent when comparing G protein bias over activating ERK1/2. To facilitate further comparisons, the ratio of bias factors obtained for each comparison were calculated from 10^(ΔΔLogRG−βarr2)/10^(ΔΔLogRG−ERK); the bias factor ratios are plotted as a summary schematic in Figure 5. Importantly, these findings demonstrate that biasing G protein signaling versus βarrestin2 recruitment or ERK 1/2 phosphorylation has the potential to be independent of one another.

Figure 5.

Schematic summarizing the SAR trends revealed when comparing the ratio of Bias Factors for each assay. Ratios were generated by dividing the bias factors for G protein vs βarr2 by the bias factors for G vs ERK1/2 activation from Table 2. A trend can be seen wherein the thiophenyl substitution increases the bias between G protein and ERK activation (denominator) resulting in a decrease in the ratio. The pyridyl substitution decreases the bias for G protein vs ERK activation (denominator) producing an increase in the ratio.

In summary, through structural modification of the 4-N substituent of the triazole scaffold we were able identify three series of compounds with conserved substitutions that have little effects on altering the bias between G protein signaling and βarrestin2 recruitment, but produce pronounced and conserved variations in bias between G protein signaling and ERK1/2 activation. If only considered for the G protein bias over βarrestin2 recruitment profiles, little difference would be evident among the nine compounds. By revealing the differences in the degrees of bias against ERK1/2 activation, these compounds will serve as important probes for evaluating how the different aspects of biased signaling will be reflected in other pharmacological as well as physiological effects at KOR. What remains is the question of how these compounds, which clearly differ in the cell-based assays, will perform in the endogenous setting. Since bias is highly context dependent (the receptor can only interact with intracellular components that are expressed where the receptor is expressed for example), further studies with these compounds will be necessary in an endogenous setting. Therefore, these studies inform only as to the differences between how the compounds can perform under the conditions analyzed and in comparison to the performance of a reference agonist, U69,593. Studies in endogenous tissues and in vivo will help to understand how bias profiles in cell based assays can be predictive (or not) of signaling induced at the multiple and diverse expression locations of the KOR in vivo.

METHODS

Compounds and Reagents for Biological Studies

Control (+)-(5α,7α,8β)-N-methyl-N-(7-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-oxaspiro(4.5)dec-8-yl)-benzeneacetamide (U69,593) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. U69,593 was prepared in ethanol as a 10 mM stock, and test compounds were prepared as 10 mM stocks in DMSO (Fisher). All compounds were then diluted further in DMSO and then to working concentrations in vehicle for each assay without exceeding 1% DMSO or ethanol concentrations. [35S]GTPγS was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Waltham, MA). Phospho-ERK1/2 and total ERK1/2 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA) and Li-Cor secondary antibodies (antirabbit IRDye800CW and antimouse IRDye680LT) were purchased from Li-Cor Biosciences (Lincoln, NE).

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Previously described Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells virally transfected to express HA-tagged recombinant human kappa opioid receptors (CHO-hKOR) were maintained in DMEM/F-12 media (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 500 μg/mL Geneticin.25,29 A stable U2OS cell line expressing hKOR and βarrrestin2-eGFP (U2OS-hKOR-βarrestin2-GFP) was a gift from Dr. Lawrence Barak, Duke University. These cells were maintained in minimum Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 500 μg/mL Geneticin, and 50 μg/mL zeocin. All cells were grown at 37 °C (5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity).

[35S]GTPγS Coupling

[35S]GTPγS Coupling was performed following a previously published protocol.25,29 Briefly, cells were serum-starved for 1 h, collected in 5 mM EDTA, and stored at −80 °C until needed. Membranes were prepared in membrane preparation buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). Each reaction was performed at room temperature for 1 h and contained 15 μg of membrane protein, ~0.1 nM [35S]GTPγS, and increasing concentrations of test compound to yield a total volume of 200 μL in assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 3 μM GDP). Reactions were quenched using a 96-well plate harvester (Brandel Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) and filtered through GF/B filters (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Filters were dried and imaged with a TopCount NXT high throughput screening microplate scintillation and luminescence counter (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

βArrestin2 Imaging

βArrestin2 imaging was performed following a previously published protocol.29 In short, U2OS-hKOR-βarr2-GFP cells were plated at a cell density of 5000 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C overnight. After a 30 min serum starve, cells were treated with increasing drug concentration for 20 min at 37 °C and fixed with prewarmed 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with Hoechst stain (1:000) for 30 min. Images were acquired with a ×20 objective on the CellInsight High Content Screening Platform (Thermo Scientific) and the number of spots per cell was determined using the Cellomics Spot Detector BioApplication algorithm (version 6.0).

In-Cell Western ERK1/2 Phosphorylation

Assay was performed following previously published protocols.25,29 Briefly, hKOR-CHO cells were plated in 384-well plate at 15 000 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C overnight. After a 1 h serum starve and 10 min drug treatment, cells were fixed, permeabilized, blocked, and stained with primary antibodies for phosphorylated ERK1/2 and total-ERK1/2 (1:300 and 1:400, respectively) at 4 °C overnight. Cells were imaged with Li-Cor secondary antibodies (antirabbit IRDye800CW, 1:500; anti-mouse IRDye680LT, 1:1500) using an Odyssey Infrared Imager (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) at 700 and 800 nm.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Concentration response curves were generated using three-parameter nonlinear regression analysis on GraphPad Prism 6.01 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). In each experiment, compound concentrations were run in parallel between 2 and 4 replicates in each individual experiment and n ≥ 3 for independent experiments was performed. In each individual experiment, compounds were normalized to the maximal U69,593 stimulation and the nonlinear regression analysis performed on each individual curve were averaged to yield efficacy and potency values reported as the mean ± SEM.

In order to determine the bias of the test ligands, each data set was fit to the operational model.37,38 This form of bias analysis employs a reference ligand that is assumed to be a full neutral agonist (i.e., the reference agonist activates all response pathways equally and does not exhibit a preference for one pathway over another). In the experiments presented here, U69,593 was used as the reference agonist and the U69,593 concentration curves were fit to the equation, from Griffin et al.,37 in each set of experiments:

| (1) |

In this equation, top represents the maximum response of the system, bottom represents the basal level of stimulation in the system, n represents the transducer slope, LogX represents the log of the concentration of U69,593 used (expressed in molar units), and LogKreference represents the log of the affinity constant of U69,593. When this equation is applied to the concentration–response curve, a value for the LogRreference parameter is produced. LogRreference is a single composite parameter that represents the product of the intrinsic agonist activity of the reference agonist (otherwise known as the τreference of the reference compound) and the affinity constant of the reference agonist (LogKreference).

By combining τreference and LogKreference into a single parameter in the equation, it is possible to achieve a highly accurate estimate of the LogRreference. It is not possible to directly estimate either τreference or LogKreference individually. Similarly, each test compound was fit to the equation, from Griffin et al., in each set of experiments:

| (2) |

This equation shares many parameter definitions with eq 1. Specifically, top, bottom, n, and LogR are all identical to the parameters defined for eq 1. Similarly, LogKtest represents the log of the affinity constant of the test agonist and LogX represents the log of the concentration of the test agonist used (in molar units). When the test agonist is fit with eq 2 and the reference agonist is simultaneously fit with eq 1, the value of LogRreference is held constant for the two equations. The parameter ΔLogR is defined as the difference between the LogRtest of the test agonist and the LogRreference (ΔLogR = LogRTest − LogRreference). Since the LogRreference is held constant between the two equations, the ΔLogR of each test agonist can be directly determined in each experiment. In order to determine the bias of a test ligand for different signaling cascades, the ΔLogR of each test agonist in multiple experiments was averaged and the difference in this averaged ΔLogR for each test agonist, in each response was calculated as

| (3) |

This difference in the ΔLogR of the test agonist for the two measures of response, defined as ΔΔLogR, provides a measure of the bias of the test agonist between the two responses. Specifically, the bias factor of each test agonist is defined as the antilog of the ΔΔLogR.38 The 95% confidence interval of the test agonists’ ΔΔLogR values (Table 2) support the preliminary finding that each test agonist is biased for G protein coupling over the other pathways under investigation.

Several parameters were constrained in this analysis in order to achieve accurate measures of each test agonist’s ΔLogR. As stated above, the LogRreference of the reference agonist was held constant when applied to both the test agonist and the reference agonist. Additionally the parameter n, the transducer slope, was also constrained to be shared for all agonists in each experiment. Similarly, the Bottom and Top parameters were shared for all agonists because the basal and maximal response of the system can be assumed to be the same for all agoinsts. The affinity constant of the test agonist, LogKtest, was constrained to the range of 1fM to 1 M, and the ΔLogR was constrained so that the absolute value of the ΔLogR of the test agonist was less than 10. The constraints were applied to the LogKtest and ΔLogR we chose in order to allow the fitted values for these parameters to be interpreted as meaningful and useful.

Compounds and Reagents for Chemical Synthesis

Except as noted below, reagents and materials were purchased from commercial vendors (Sigma, Alfa Aesar, TCI America, Fisher Scientific) and used as received. Ethyl ether, toluene, THF, MeCN, and CH2Cl2 were degassed with nitrogen and passed through two columns of basic alumina on an Innovative Technology solvent purification system. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AM 400 spectrometer (operating at 400 and 100 MHz respectively) in CDCl3 with 0.03% TMS as an internal standard, unless otherwise specified. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (ppm) downfield from TMS. 13C Multiplicities were determined with the aid of an APT pulse sequence, differentiating the signals for methyl and methine carbons as “d” from methylene and quaternary carbons as “u”. The infrared (IR) spectra were acquired as thin films using a universal ATR sampling accessory on a PerkinElmer Spectrum 100 FT-IR spectrometer and the absorption frequencies are reported in cm−1. Melting points were determined on a Stanford Research Systems Optimelt automated melting point system interfaced through a PC and are uncorrected.

HPLC/MS analysis was carried out with gradient elution (5% CH3CN to 100% CH3CN) on an Agilent 1200 HPLC with a photodiode array UV detector and an Agilent 6224 TOF mass spectrometer (also used to produce high resolution mass spectra). One of two column/mobile phase conditions were chosen to promote the target’s neutral state (0.02% formic acid with Waters Atlantis T3 5um, 19 × 150 mm; or pH 9.8 NH4OH with Waters XBridge C18 5 um, 19 × 150 mm).

The furan- and thiophene-containing thione substrates were synthesized as previously described.30 The synthesis of the 3-pyridine-containing thione substrate as well as HPLC chromatograms and images of the NMR spectra are provided in the Supporting Information.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Triazole Analogues

The previously reported protocol was utilized for the synthesis of novel triazole analogues.30 Thus, the thione scaffold (0.1–0.3 mmol), K2CO3 (2 equiv), and the benzyl halide (1.2 equiv) were combined in acetone (15 mL/mmol substrate) and stirred at rt in a sealed vial. After 15 h, the solvent was removed and the residue washed with CH2Cl2 (2 × 3 mL) and filtered. The combined filtrates were evaporated and purified by silica gel chromatography to afford the triazole thioether product.

1.1. 2-(5-((2-Chloro-5-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)thio)-4-(furan-2-yl-methyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)pyridine

The furan-containing thione (52 mg, 0.20 mmol) and 2-chloro-5-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl bromide (66 mg, 0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were reacted according to the general procedure to afford the product as a white solid (74 mg, 0.17 mmol, 83% yield). Mp = 109–114 °C; Rf = 0.51 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.65 (s, 2H), 5.81 (s, 2H), 6.12 (d, J = 2.8 Hz, 1H), 6.19 (dd, J = 2.0, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (ddd, J = 1.2, 4.8, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.52 (m, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (dt, J = 1.6, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.64 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, APT pulse sequence) δ d 109.0, 110.4, 123.4, 124.1, 125.9 (q, J = 3.6 Hz), 128.1 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 130.2, 137.0, 142.7, 148.5; u 35.4, 41.9, 123.4 (d, J = 273.3 Hz), 129.5 (q, J = 33.2 Hz), 135.8, 138.1, 147.7, 148.9, 152.1, 152.8. IR (neat) 1590, 1463, 1446, 1423 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H15ClF3N4OS ([M + H]+), 451.0607; found, 451.0619. HPLC purity = 99.6%.

1.2. 2-(5-((2-Chloro-5-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)thio)-4-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)pyridine

The thiophene-containing thione (55 mg, 0.20 mmol) and 2-chloro-5-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl bromide (66 mg, 0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were reacted according to the general procedure to afford the product as a white solid (90 mg, 0.19 mmol, 96% yield). Mp = 118–121 °C; Rf = 0.58 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.65 (s, 2H), 5.90 (s, 2H), 6.84 (dd, J = 3.6, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (dd, J = 1.2, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (dd, J = 1.2, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (ddd, J = 1.2, 4.8, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.44–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.73 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (dt, J = 1.6, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (td, J = 1.2, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.66 (ddd, J = 0.8, 2.0, 4.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, APT pulse sequence) δ d 123.3, 124.2, 126.0 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 126.4, 126.5, 127.7, 128.1 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 130.2, 137.1, 148.5; u 35.4, 43.7, 123.4 (d, J = 273.5 Hz), 129.3 (q, J = 33.1 Hz), 135.8, 137.7, 138.1, 147.6, 151.8, 152.6; IR (neat) 1590, 1463, 1445, 1417 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H15ClF3N4S2 ([M + H]+), 467.0379; found, 467.0375. HPLC purity = 100%.

1.3. 2-(5-((2-Chloro-5-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)thio)-4-(pyridin-3-ylmethyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)pyridine

The 3-pyridine-containing thione (50 mg, 0.19 mmol) and 2-chloro-5-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl bromide (61 mg, 0.22 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were reacted according to the general procedure to afford the product as an off-white solid (64 mg, 0.14 mmol, 75% yield). Mp = 122–123 °C; Rf = 0.54 (EtOAc). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.65 (s, 2H), 5.76 (s, 2H), 7.14 (ddd, J = 0.8, 4.8, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (ddd, J = 1.2, 4.8, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (td, J = 2.0, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.46–7.51 (m, 2H), 7.74 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (dt, J = 2.0, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (td, J = 1.2, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (dd, J = 1.6, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (qd, J = 0.8, 5.2 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, APT pulse sequence) δ d 123.4, 123.5, 124.4, 126.1 (q, J = 3.6 Hz), 128.2 (q, J = 3.7 Hz), 130.3, 135.0, 137.3, 148.7, 149.3, 149.4; u 35.3, 46.5, 123.5 (d, J = 273.4 Hz), 129.6 (q, J = 33.3 Hz), 131.5, 135.7, 138.1, 147.5, 152.3, 153.0. IR (neat) 1590, 1465, 1446, 1420, 1328 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C21H16ClF3N5S ([M + H]+), 462.0767; found, 462.0789. HPLC purity = 98.2%.

2.1. 2-(5-((4-Iodobenzyl)thio)-4-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)pyridine

The furan-containing thione (52 mg, 0.20 mmol) and 4-iodobenzyl bromide (71 mg, 0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were reacted according to the general procedure to afford the product as a tan solid (25 mg, 0.05 mmol, 27% yield). Mp = 123–126 °C; Rf = 0.31 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.43 (s, 2H), 5.82 (s, 2H), 6.11 (dd, J = 0.4, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 6.21 (dd, J = 1.6, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (dd, J = 0.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.34 (ddd, J = 1.2, 4.8, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (td, J = 1.6, 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (dt, J = 1.6, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (ddd, J = 0.8, 1.6, 4.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, APT pulse sequence) δ d 109.0, 110.5, 123.4, 124.2, 131.1, 137.0, 137.8, 142.7, 148.6; u 37.5, 42.0, 93.4, 136.6, 147.8, 149.0, 152.6, 152.7; IR (neat) 1589, 1483, 1462, 1445, 1421 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C19H16IN4OS ([M + H]+), 475.0089; found, 475.0098. HPLC purity = 98.3%.

2.2. 2-(5-((4-Iodobenzyl)thio)-4-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)pyridine

The thiopehene-containing thione2 (55 mg, 0.20 mmol) and 4-iodobenzyl bromide (71 mg, 0.24 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were reacted according to the general procedure to afford the product as a white solid (93 mg, 0.19 mmol, 95% yield). Mp = 125–128 °C; Rf = 0.34 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.42 (s, 2H), 5.91 (s, 2H), 6.85 (dd, J = 3.6, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (dd, J = 1.2, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.12–7.16 (m, 3H), 7.34 (ddd, J = 0.8, 5.2, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (td, J = 2.0, 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (dt, J = 1.6, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.67 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, APT pulse sequence) δ d 123.3, 124.3, 126.4, 126.6, 127.7, 131.2, 137.2, 137.8, 148.6; u 37.5, 43.8, 93.5, 136.6, 137.9, 147.8, 152.4, 152.5. IR (neat) 1588, 1568, 1482, 1462, 1445, 1417 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C19H16IN4S2 ([M + H]+), 490.9861; found, 490.9866. HPLC purity = 97.9%.

2.3. 2-(5-((4-Iodobenzyl)thio)-4-(pyridin-3-ylmethyl)-4H-1,2,4-tri-azol-3-yl)pyridine

The 3-pyridine-containing thione (49 mg, 0.18 mmol) and 4-iodobenzyl bromide (65 mg, 0.22 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were reacted according to the general procedure to afford the product as a colorless oil (72 mg, 0.15 mmol, 82% yield); Rf = 0.34 (EtOAc). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.42 (s, 2H), 5.77 (s, 2H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (dd, J = 4.8, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.29–7.33 (m, 2H), 7.59 (td, J = 2.0, 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.81 (dt, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (td, J = 0.8, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.48 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (s, 1H), 8.56 (qd, J = 0.8, 4.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, APT pulse sequence) δ d 123.4, 123.6, 124.4, 131.1, 135.0, 137.3, 137.9, 148.8, 149.2, 149.3; u 37.3, 46.5, 93.6, 131.7, 136.4, 147.5, 152.7, 152.9; IR (neat) 1588, 1482, 1464, 1446, 1419 cm−1; HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H17IN5S ([M + H]+), 486.0249; found, 486.0257. HPLC purity = 98.4%.

3.1. 2-(5-((4-Bromobenzyl)thio)-4-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-4H-1,2,4-tri-azol-3-yl)pyridine

The furan-containing thione (63 mg, 0.24 mmol) and 4-bromobenzyl bromide (73 mg, 0.29 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were reacted according to the general procedure to afford the product as a pale yellow solid (59 mg, 0.14 mmol, 57% yield). Mp = 111–115 °C; Rf = 0.31 (1:1 hexanes/EtOAc). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.43 (s, 2H), 5.81 (s, 2H), 6.10 (dd, J = 0.8, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (dd, J = 1.6, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (dd, J = 0.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.33 (ddd, J = 1.2, 5.2, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (td, J = 2.0, 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (dt, J = 1.6, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.26 (td, J = 0.8, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.63 (ddd, J = 0.8, 1.6, 4.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, APT pulse sequence) δ d 109.1, 110.5, 123.5, 124.2, 130.9, 131.9, 137.1, 142.7, 148.7; u 37.5, 42.0, 121.9, 136.0, 147.8, 149.1, 152.7, 152.8. IR (neat) 1589, 1486, 1462, 1445, 1421 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C19H16BrN4OS ([M + H]+), 427.0228; found, 427.0211. HPLC purity = 99.8%.

3.2. 2-(5-((4-Bromobenzyl)thio)-4-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)pyridine

The material was prepared as previously described.1 HPLC purity = 100%.

3.3. 2-(5-((4-Bromobenzyl)thio)-4-(pyridin-3-ylmethyl)-4H-1,2,4-triazol-3-yl)pyridine

The 3-pyridine-containing thione (75 mg, 0.28 mmol) and 4-bromobenzyl bromide (84 mg, 0.33 mmol, 1.2 equiv) were reacted according to the general procedure to afford the product as a light yellow oil (73 mg, 0.17 mmol, 60% yield). Rf = 0.67 (10% MeOH in CH2Cl2). 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 4.43 (s, 2H), 5.77 (s, 2H), 7.13 (dd, J = 4.8, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (td, J = 2.0, 8.8 Hz, 2H), 7.29–7.33 (m, 2H), 7.39 (td, J = 2.0, 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (dt, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (td, J = 0.8, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 8.47 (dd, J = 0.8, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 8.52 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 1H), 8.55 (qd, J = 0.8, 4.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3, APT pulse sequence) δ d 123.4, 123.5, 124.4, 130.9, 131.9, 134.9, 137.2, 148.7, 149.2, 149.3; u 37.2, 46.5, 121.9, 131.6, 135.8, 147.8, 152.7, 152.8. IR (neat) 1589, 1486, 1464, 1446, 1419 cm−1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C20H17BrN5S ([M + H]+), 438.0388; found, 438.0391. HPLC purity = 99.8%.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01 DA031927 to L.M.B. and J.A.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental details and characterization for all new compounds. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00092.

Author Contributions

K.J.F., S.R.S., E.Y., T.E.P., J.A. designed compounds and performed chemical synthesis. K.M.L., E.L.S. performed pharmacological assays. K.M.L., E.L.S., L.M.B. designed the studies and performed analysis of the data. L.M.L., K.J.F., E.L.S., T.E.P., J.A., and L.M.B. wrote the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Pasternak GW. Multiple opiate receptors: [3H]-Ethylketocyclazocine receptor binding and ketocyclazocine analgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:3691–1694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vonvoigtlander PF, Lahti RA, Ludens JH. U-50,488: A selective and structurally novel non-mu (kappa) opioid agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;224:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dykstra LA, Gmerek DE, Winger G, Woods JH. Kappa opioids in rhesus monkeys. I. Diuresis, sedation, analgesia and discriminative stimulus effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;242:413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millan MJ. Kappa-opioid receptor-mediated antinociception in the rat. I. Comparative actions of mu- and kappa-opioids against noxious thermal, pressure and electrical stimuli. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;251:334–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glick SD, Maisonneuve IM, Raucci J, Archer S. Kappa opioid inhibition of morphine and cocaine self-administration in rats. Brain Res. 1995;681:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00306-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negus SS, Mello NK, Portoghese PS, Lin CE. Effects of kappa opioids on cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:44–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schenk S, Partridge B, Shippenberg TS. U69593, a kappa-opioid agonist, decreases cocaine self-administration and decreases cocaine-produced drug-seeking. Psychopharmacology. 1999;144:339–346. doi: 10.1007/s002130051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van’t Veer A, Bechtholt AJ, Onvani S, Potter D, Wang Y, Liu-Chen LY, Schutz G, Chartoff EH, Rudolph U, Cohen BM, Carlezon WA., Jr Ablation of kappa-opioid receptors from brain dopamine neurons has anxiolytic-like effects and enhances cocaine-induced plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1585–1597. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh SL, Geter-Douglas B, Strain EC, Bigelow GE. Enadoline and butorphanol: evaluation of kappa-agonists on cocaine pharmacodynamics and cocaine self-administration in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:147–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Land BB, Bruchas MR, Schattauer S, Giardino WJ, Aita M, Messinger D, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD, Chavkin C. Activation of the kappa opioid receptor in the dorsal raphe nucleus mediates the aversive effects of stress and reinstates drug seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19168–19173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910705106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aldrich JV, Patkar KA, McLaughlin JP. Zyklophin, a systemically active selective kappa opioid receptor peptide antagonist with short duration of action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18396–18401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910180106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodkin JA, Zornberg GL, Lukas SE, Cole JO. Buprenorphine treatment of refractory depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;15:49–57. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199502000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knoll AT, Muschamp JW, Sillivan SE, Ferguson D, Dietz DM, Meloni EG, Carroll FI, Nestler EJ, Konradi C, Carlezon WA., Jr Kappa opioid receptor signaling in the basolateral amygdala regulates conditioned fear and anxiety in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mague SD, Pliakas AM, Todtenkopf MS, Tomasiewicz HC, Zhang Y, Stevens WC, Jr, Jones RM, Portoghese PS, Carlezon WA., Jr Antidepressant-like effects of kappa-opioid receptor antagonists in the forced swim test in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:323–330. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kardon AP, Polgar E, Hachisuka J, Snyder LM, Cameron D, Savage S, Cai X, Karnup S, Fan CR, Hemenway GM, Bernard CS, Schwartz ES, Nagase H, Schwarzer C, Watanabe M, Furuta T, Kaneko T, Koerber HR, Todd AJ, Ross SE. Dynorphin acts as a neuromodulator to inhibit itch in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Neuron. 2014;82:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phan NQ, Lotts T, Antal A, Bernhard JD, Stander S. Systemic kappa opioid receptor agonists in the treatment of chronic pruritus: A literature review. Acta Derm-Venereol. 2012;92:555–560. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inan S, Dun NJ, Cowan A. Nalfurafine prevents 5′-guanidinonaltrindole- and compound 48/80-induced spinal c-fos expression and attenuates 5′-guanidinonaltrindole-elicited scratching behavior in mice. Neuroscience. 2009;163:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inan S, Cowan A. Kappa opioid agonists suppress chloroquine-induced scratching in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;502:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knoll AT, Carlezon WA., Jr Dynorphin, stress, and depression. Brain Res. 2010;1314:56–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Land BB, Bruchas MR, Lemos JC, Xu M, Melief EJ, Chavkin C. The dysphoric component of stress is encoded by activation of the dynorphin kappa-opioid system. J Neurosci. 2008;28:407–414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4458-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeiffer A, Brantl V, Herz A, Emrich HM. Psychotomimesis mediated by kappa opiate receptors. Science. 1986;233:774–776. doi: 10.1126/science.3016896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth BL, Baner K, Westkaemper R, Siebert D, Rice KC, Steinberg S, Ernsberger P, Rothman RB. Salvinorin A: A potent naturally occurring nonnitrogenous kappa opioid selective agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11934–11939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182234399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruchas MR, Chavkin C. Kinase cascades and ligand-directed signaling at the kappa opioid receptor. Psychopharmacology. 2010;210:137–147. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1806-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White KL, Scopton AP, Rives ML, Bikbulatov RV, Polepally PR, Brown PJ, Kenakin T, Javitch JA, Zjawiony JK, Roth BL. Identification of novel functionally selective kappa-opioid receptor scaffolds. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;85:83–90. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.089649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmid CL, Streicher JM, Groer CE, Munro TA, Zhou L, Bohn LM. Functional selectivity of 6′-guanidinonaltrindole (6′-GNTI) at kappa-opioid receptors in striatal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:22387–22398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.476234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenakin T. Functional selectivity through protean and biased agonism: Who steers the ship? Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1393–1401. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urban JD, Clarke WP, von Zastrow M, Nichols DE, Kobilka B, Weinstein H, Javitch JA, Roth BL, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM, Miller KJ, Spedding M, Mailman RB. Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mailman RB. GPCR functional selectivity has therapeutic impact. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:390–396. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou L, Lovell KM, Frankowski KJ, Slauson SR, Phillips AM, Streicher JM, Stahl E, Schmid CL, Hodder P, Madoux F, Cameron MD, Prisinzano TE, Aube J, Bohn LM. Development of functionally selective, small molecule agonists at kappa opioid receptors. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:36703–36716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.504381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frankowski KJ, Hedrick MP, Gosalia P, Li K, Shi S, Whipple D, Ghosh P, Prisinzano TE, Schoenen FJ, Su Y, Vasile S, Sergienko E, Gray W, Hariharan S, Milan L, Heynen-Genel S, Mangravita-Novo A, Vicchiarelli M, Smith LH, Streicher JM, Caron MG, Barak LS, Bohn LM, Chung TD, Aube J. Discovery of Small Molecule Kappa Opioid Receptor Agonist and Antagonist Chemotypes through a HTS and Hit Refinement Strategy. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:221–236. doi: 10.1021/cn200128x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLennan GP, Kiss A, Miyatake M, Belcheva MM, Chambers KT, Pozek JJ, Mohabbat Y, Moyer RA, Bohn LM, Coscia CJ. Kappa opioids promote the proliferation of astrocytes via Gbetagamma and beta-arrestin 2-dependent MAPK-mediated pathways. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1753–1765. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohn LM, Belcheva MM, Coscia CJ. Mitogenic signaling via endogenous kappa-opioid receptors in C6 glioma cells: Evidence for the involvement of protein kinase C and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade. J Neurochem. 2000;74:564–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.740564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belcheva MM, Clark AL, Haas PD, Serna JS, Hahn JW, Kiss A, Coscia CJ. Mu and kappa opioid receptors activate ERK/MAPK via different protein kinase C isoforms and secondary messengers in astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27662–27669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502593200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruchas MR, Land BB, Aita M, Xu M, Barot SK, Li S, Chavkin C. Stress-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation mediates kappa-opioid-dependent dysphoria. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11614–11623. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3769-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruchas MR, Macey TA, Lowe JD, Chavkin C. Kappa opioid receptor activation of p38 MAPK is GRK3- and arrestin-dependent in neurons and astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:18081–18089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513640200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregory KJ, Hall NE, Tobin AB, Sexton PM, Christopoulos A. Identification of orthosteric and allosteric site mutations in M2 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors that contribute to ligand-selective signaling bias. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7459–7474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffin MT, Figueroa KW, Liller S, Ehlert FJ. Estimation of agonist activity at G protein-coupled receptors: Analysis of M2 muscarinic receptor signaling through Gi/o,Gs, and G15. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:1193–1207. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.120857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenakin T, Watson C, Muniz-Medina V, Christopoulos A, Novick S. A simple method for quantifying functional selectivity and agonist bias. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:193–203. doi: 10.1021/cn200111m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stahl EL, Zhou L, Ehlert FJ, Bohn LM. A Novel Method for Analyzing Extremely Biased Agonism at G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2015;87:866–877. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.096503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.