Abstract

Purpose of review

To present an updated summary of the relationship between joint shape and the development of osteoarthritis, with a particular focus on osteoarthritis of the hip.

Recent findings

Osteoarthritis of the hip is highly heritable, with a genetic contribution estimated at 60%. Among the genes that have been linked to this disease are several that are involved in the development and maintenance of joint shape, including members of the Wingless (Wnt) and the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family. Several features of hip joint architecture, such as acetabular dysplasia, pistol grip deformity, wide femoral neck, altered femoral neck-shaft angle, appear to play an important role in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis and may predate the development of osteoarthritis by decades.

Summary

Gene–environment interactions play a crucial role in the development of osteoarthritis. The architecture of joint shape is determined by a complex sequence spanning embryonic, childhood, and adult life and contributes to the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis.

Keywords: bone, geometry, hip, joint shape, osteoarthritis

Introduction

Osteoarthritis, the most common form of arthritis, is characterized by the degeneration of cartilage and subchondral bone. Osteoarthritis is a frequent cause of morbidity among the elderly, and its prevalence is expected to increase even further in the coming decades [1]. Due to the enormous public health impact of this disease, significant effort has been directed toward the identification of risk factors for osteoarthritis. Although it was hypothesized as early as the 1960s that joint shape is a key predictor of osteoarthritis [2], this idea has only recently begun to be further explored.

Early paradigms of osteoarthritis pathogenesis asserted that most osteoarthritis was so-called ‘primary’ or idiopathic, resulting from chronic mechanical damage to a structurally normal joint. Later, however, it was appreciated that ‘secondary’ osteoarthritis, or osteoarthritis resulting from an identifiable predisposing factor, is much more common. Among the secondary factors involved in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis, the architecture of the joint itself is a key feature that may promote or protect from osteoarthritis. It is now known that subtle structural features of bone shape predate the development of osteoarthritis by decades in the vast majority (perhaps up to 90%) of osteoarthritis cases [2,3]. In this review, we explore the emerging picture of the complex relationship between joint shape and osteoarthritis, focusing on osteoarthritis of the hip as an illustrative example of this relationship.

Osteoarthritis of the hip is common and highly heritable

OA of the hip is extremely common. In the Rotterdam study [4], a large Dutch cohort of participants over the age of 55, radiographic hip osteoarthritis was present in 15.9% of women and 14.1% of men. In the US, the prevalence of hip osteoarthritis varies. Among elderly US Caucasians, a prevalence of 3–13% has been reported [5–7], though in at least one population of Southern Caucasians, a prevalence of over 20% was found [8]. Among African-Americans, osteoarthritis of the hip may be slightly more common than in US Caucasians [8,9]. Interestingly, for reasons that are not fully understood, the disease is relatively rare among Asians and Africans [10].

Osteoarthritis of the hip is defined for epidemiologic purposes by the radiographic combination of definite osteophytes and joint space narrowing [11]. There is relatively poor correlation, however, between radiographic hip osteoarthritis and clinical sequelae such as pain and functional limitation [12]. Across studies, only a minority of patients with mild-to-moderate radiographic hip osteoarthritis report symptoms of hip pain [4,13]. For example, in the cross-sectional Rotterdam study of community dwellers aged at least 55 years, hip pain was present in 16.0% of men and 33.2% of women with radiographic hip osteoarthritis [4]. However, with increasing severity of radiographic hip osteoarthritis, association with joint pain increases. For example, in the most severe category of radiographic hip osteoarthritis, hip pain was present in 31.0% of men and 49.1% of women [4].

Among the factors that predict the progression of radiographic hip osteoarthritis, joint shape parameters such as baseline femoral neck width and femoral head migration are important in determining osteoarthritis outcomes [6,14]. It is notable that there is apparently little overlap between architectural features associated with radiographic hip osteoarthritis and those associated with clinical hip osteoarthritis. For example, in a recent study by Waarsing and colleagues [15] using the active shape modeling (ASM) technique to assess proximal femur shape, femur shapes that predicted hip pain were distinct from femur shapes predicting the presence of radiographic hip osteoarthritis.

Human genetic studies have suggested that osteoarthritis of the hip is highly heritable [16], with a genetic contribution of approximately 60% in women according to classic twin studies after adjustment for known confounders [17]. The genetic contribution to osteoarthritis appears to differ by anatomic site, with osteoarthritis of the hand and hip showing a greater tendency to cluster within families than osteoarthritis of the knee [18]. Genome-wide association studies have identified regions of chromosomes 2, 4, 6, 7, 11, 16, and 19, and the X chromosome as harboring important genes involved in the heritability of osteoarthritis (reviewed in [19]). At least five distinct biological pathways [20–22] have been implicated in the pathogenesis of hip osteoarthritis based on these genetic studies, including inflammatory cytokine [23–31], bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) [32–34], and the Wingless (Wnt) [35–37] pathways (Table 1).

Table 1.

Selected genes associated with hip osteoarthritis

| Gene | Function | Odds ratio (95% CI or P value) |

Studies supporting association |

Studies supporting no association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asporin (ASPN) | Negative regulator of TGF-β pathway | 1.71 (CI = 1.1–2.6) | [38,39] | [40] |

| Bone morphogenetic protein 5 (BMP5) |

Regulates chondrocyte development | 3.2 (P = 0.00006) | [32,41] | [42] |

| Calmodulin 1 (CALM1) | Modulates intracellular calcium signaling |

2.40 (CI = 1.43–4.02) | [43] | [44] |

| Diodinase iodothyronine type 2 (DIO2) |

Regulates tissue levels of active thyroid hormone |

1.79 (CI = 1.37–2.34) | [45] | – |

| Frizzled-related protein (FRZB) | Antagonist of Wnt signaling | 4.1 (CI = 1.6–10.7) | [22,24,46,47] | [48] |

| Growth and differentiation factor 5 (GDF5) |

Regulates cell growth and differentiation including skeletal development; member of BMP family and TGF-β superfamily |

1.79 (CI = 1.53–2.09) | [33,34] | – |

| Interleukin-1β (IL1β) | Mediator of inflammatory response; regulates cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis |

2.9 (CI = 1.4–6.3) | [49] | [40,50] |

| IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL1RN) |

Modulates the inflammatory response |

3.3 (CI = 1.4–7.8) | [49] | [50] |

| Interleukin 4 receptor (IL4R) |

Mediates T-cell differentiation and proliferation; may play a role in chondrocyte mechanosensation [51] |

2.1 (CI = 1.3–3.5) | [52] | [40] |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Modulates inflammatory response and B-cell maturation; cartilage maintenance [53] |

0.4a (CI = 0.1–0.9) | [54] | [40] |

CI, confidence interval.

Protection from hip OA was observed for the CC 174 IL-6 gene polymorphism.

Bone morphogenetic proteins and the Wingless pathway: molecular links between joint shape and osteoarthritis

The Wnt pathway has recently gained attention for its role in both determination of joint shape and development of osteoarthritis. During skeletal development, Wnt proteins are expressed in the limb bud and at sites of synovial joint formation [55]. Alterations in this pathway lead to limb malformations in animal models [56]. In adult life, Wnt signaling continues to play an important role in joint homeostasis. Excessive activation of this pathway is involved in regulating cartilage breakdown and bony sclerosis in osteoarthritis [57], and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of Wnt pathway proteins are associated with increased susceptibility to osteoarthritis [58–61]. Antagonists of the Wnt pathway are currently in clinical development for treatment of the sclerotic bony lesions of multiple myeloma [62] and osteoporosis [63], though their efficacy has not yet been tested in osteoarthritis.

Another important group of molecules involved in both the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis and the determination of joint shape is the BMP family. BMPs and the closely related growth and differentiation factors (GDFs) comprise a large family of proteins nested within the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily (reviewed in [64]). BMPs signal through the Smad pathway or the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathway to elicit bone and cartilage formation during development as well as cell differentiation and tissue homeostasis in adult life [64]. GDF5 is required for proper digit formation in vertebrates [65,66], and overexpression of BMP2 and BMP4 dramatically alters joint phenotype in the developing chick limb bud [67]. Polymorphisms of proteins in this family that have been associated with hip osteoarthritis include BMP5 [32,34,68] and GDF5 [68,69].

Gene–environment interactions in hip osteoarthritis

Animal studies show that skeletal shape is determined by a tightly regulated genetic program during development [70]. In the mature organism, joint shape is maintained through a dynamic process of homeostasis and repair, and changes in joint shape continue to occur throughout adult life [71]. The dynamic regulation of bone shape makes the analysis of a relationship between bone shape and osteoarthritis complex, as changes in joint shape may both predispose to osteoarthritis and occur as a result of osteoarthritis itself.

Several environmental factors have been identified that predispose to hip osteoarthritis. Gelber and colleagues [72] performed a prospective cohort study of 1321 former medical students with a mean baseline age of 22 years with 36 years of follow-up and found that a history of hip injury was associated with a relative risk (RR) of 3.50 for subsequent hip osteoarthritis [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.84–14.69]. Croft and colleagues [73] performed a cross-sectional study of 250 male patients in rural general practice clinics in the UK and found that the occupation of farming was associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 9.3 for development of radiographic hip osteoarthritis (95% CI 1.8–33.8). Vingard and colleagues [74] in a case-control study of 233 men with early onset (<age 49) of severe hip osteoarthritis requiring joint replacement and 302 controls found that exposure to sports or other activities with high mechanical load substantially increased the odds of hip osteoarthritis (OR 4.3, 95% CI 1.7–11.0). Interestingly, Nevitt and colleagues [75] evaluated the effect of estrogen use in a cohort of elderly Caucasian women followed for a median of 8.3 years and found that exogenous estrogen use was associated with a decreased risk of osteoarthritis of the hip (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.40–0.82). Environmental factors may influence the development of osteoarthritis more or less strongly in particular anatomic contexts. For example, one study found an interaction between acetabular shape and workload in the development of radiographic hip osteoarthritis [76].

Known associations between hip shape and osteoarthritis

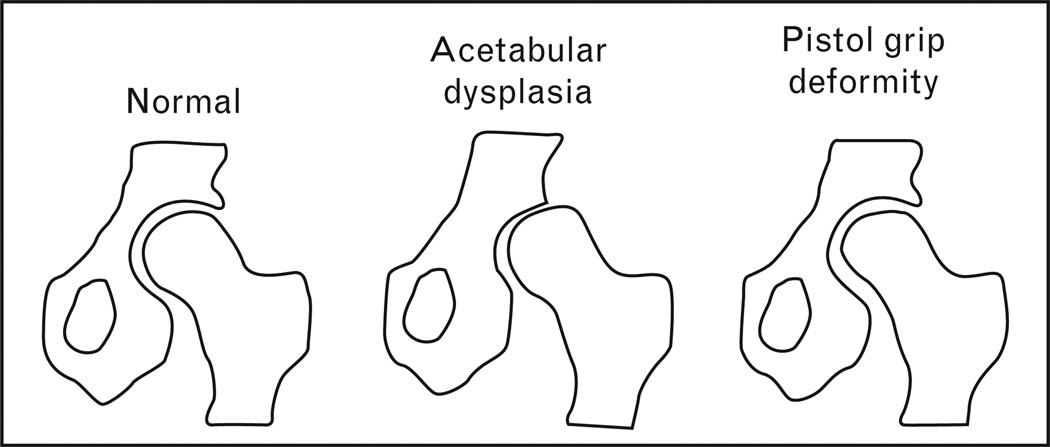

Several specific hip shape variations have been associated with osteoarthritis, as discussed below (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Various femoral head and acetabular shape variants are associated with osteoarthritis.

For example, a shallow acetabular cup is one type of acetabular dysplasia that is linked to incident osteoarthritis. In addition, a nonspherical, elongaged femoral head is a cause of the so-called ‘pistol grip’ deformity, which is associated with impingement and early osteoarthritis.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is the most common cause of osteoarthritis in young adults [77]. Congenital subluxation, Legg-Calvé-Perthe’s disease, and slipped capital femoral epiphysis are developmental abnormalities that have all been linked with hip osteoarthritis in adulthood [2,3,78]. Despite this, the presence of DDH is not always concordant with the development of hip osteoarthritis. In the Japanese, for example, DDH is quite common, yet osteoarthritis is rare [79,80]. Despite this, a history of congenital dislocation of the hip or acetabular dysplasia is usually present in Japanese who do develop osteoarthritis [77].

Acetabular dysplasia

Acetabular dysplasia describes a series of anatomic variants in the shape of the acetabular ‘cup’ of the hip joint. Acetabular dysplasia is quite common in Europeans, with a prevalence of 3.4% in one large Danish series [81]. Interestingly, the European population also has a relatively high prevalence of hip osteoarthritis.

As early as 1965, it was suggested that variants in acetabular shape predispose to osteoarthritis of the hip [2]. Several studies estimate that between 25 and 40% of hip osteoarthritis is attributable to subtle forms of acetabular dysplasia [2,3,82]. Acetabular retroversion, in which the acetabular cup is posterolaterally rather than anterolaterally oriented, is one example of a type of acetabular dysplasia associated with hip osteoarthritis [83].

An obvious question in light of this observation is whether changes in acetabular shape occur before or as a result of osteoarthritis. One study shedding light on this question was that of Reijman and colleagues [76], who studied 835 patients aged 55 years or older at baseline in the Rotterdam cohort for a mean of 6.6 years of follow-up and found that the presence of acetabular dysplasia at baseline was associated with an increased risk of incident hip osteoarthritis. Consistent with the idea that changes in acetabular shape predate the development of arthritis, Lane and colleagues [38] found an association between mild acetabular dysplasia and incident radiographic hip osteoarthritis in postmenopausal women followed for a mean of 8.3 years (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.0–7.9). These studies suggest that dysplastic acetabular shape is a risk factor that acts together with a second factor, possibly age and or low-grade inflammation, in the development of osteoarthritis.

Wagner and colleagues [39] performed a case-control study with cartilage specimens obtained from 22 young adults (mean age 30.4 years) undergoing surgery for painful femoroacetabular impingement and six age-matched cadaveric controls. They found that hyaline cartilage from case participants showed dramatically increased immunohistochemical staining for several markers of osteoarthritis [tenascin-C, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP), and collagenase cleavage product (COL2–3/4Clong)] as well as increased expression of collagen type I and II transcripts by in-situ hybridization. These changes mirrored those of patients with advanced osteoarthritis. This study provides evidence that, even in young adults without radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis, molecular changes in cartilage structure resembling those of advanced osteoarthritis are already underway.

When present with other hip osteoarthritis risk factors, acetabular dysplasia may increase an individual’s risk of osteoarthritis even further. For example, the combination of acetabular dysplasia and an abnormally shaped femoral head have been shown to increase the risk of osteoarthritis progression after surgical repair of the acetabular defect [77]. In addition, despite inconsistent evidence linking body mass index (BMI) to osteoarthritis of the hip [40–44], Reijman and colleagues [76] found that patients with low BMI had an increased risk of incident hip osteoarthritis in the setting of acetabular dysplasia, though the clinical significance of this observation is not yet known.

Pistol-grip deformity and wide femoral neck

In addition to changes in the acetabulum, structural features of the femur have been linked to osteoarthritis. For example, a nonspherical femoral head produces the so-called ‘pistol-grip’ deformity, causing impingement of the femoral head on the acetabulum, likely the mechanism by which this lesion predisposes to osteoarthritis [45]. The prevalence of pistol-grip deformity has been estimated at approximately 8% [46], and this deformity may be more common in men than women [45]. In a study comparing 1007 cases with severe clinical and radiographic hip osteoarthritis recruited from orthopedic surgery lists to 1123 controls without radiographic hip osteoarthritis, Doherty and colleagues [45] estimated an OR of 6.95 (95% CI 4.64–10.41) for the association between pistol grip deformity and hip osteoarthritis.

At least two studies have identified a widened femoral neck as associated with hip osteoarthritis [47,48]. Javaid and colleagues [47] examined 5245 elderly Caucasian women in the study of osteoporotic fractures (mean age 72.6 years) with mean follow-up of 8.3 years and found that a wider femoral neck was associated with both prevalent and incident cases of radiographic hip osteoarthritis. This study suggests that femoral neck widening may precede or occur very early in the development of hip osteoarthritis.

Alterations in femoral neck-shaft angle

There is no consensus regarding the association of neck-shaft angle and the development of hip osteoarthritis, with study reports ranging from no association [47,49] to a positive correlation between a larger angle [50], a smaller angle [51], or both [45] with osteoarthritis. During the progression of hip osteoarthritis, the femoral head flattens and the femoral neck shortens [52]. Thus, the heterogeneity of results in studies examining a potential correlation between neck-shaft angle and osteoarthritis may reflect the fact that this angle may change as a result of osteoarthritis in addition to its likely role in contributing to osteoarthritis. Interestingly, Gregory and colleagues [52] showed in a prospective cohort that distinct differences in shape of the femur preceded development of osteoarthritis. In other words, differences in the shape of the femoral head and neck were present on pelvic radiographs before any detectable evidence of radiographic hip osteoarthritis. Furthermore, differences in hip shape present prior to the development of osteoarthritis predicted progression to hip replacement over the 6-year follow-up period, indicating that hip shape may predict the severity as well as the presence of osteoarthritis [52].

Global shape of the proximal femur

The hip shape variants discussed above were generally defined using linear measurements measured manually or electronically on radiographs. In recent years, however, the techniques used to study the association between proximal femur shape and hip osteoarthritis have included ASM [53]. In this method, a statistical model of the shape of an object is developed from a multipoint outline [54]. Applied to measurements of proximal femur shape, this method has several advantages over traditional geometric measurements such as femoral neck length or width, as it captures a global representation of shape rather than a limited subset of components of that shape. Using this technique, Lynch and colleagues [84] studied elderly women in the study of osteoporotic fracture population and found that variations in the relative size and shape of the femoral head and neck at baseline predicted incident hip osteoarthritis. Specifically, three distinct hip shapes, or ‘modes’, were associated with incident hip osteoarthritis with ORs ranging from 1.73 to 2.31. The shape of mode 3, which accounted for the greatest amount of variability in overall proximal femur shape of the three shapes identified, was characterized by a larger femoral head size and a longer, slightly thinner femoral neck, reinforcing the idea that hip shape changes predate the development of radiographic hip osteoarthritis in many cases.

Conclusion

The shape of diarthrodial joints is determined by a complex developmental program and by a dynamic remodeling process in the adult organism. Joint shape appears to be an important determinant of hip osteoarthritis, and joint shape is in turn altered by the disease process of osteoarthritis, leading to an intricate interplay between joint shape and arthritis. Molecular links that shed light on the nature of this interplay have surfaced in recent years. Future research including the development of increasingly sophisticated analysis methods for human genome-wide association studies will likely continue to illuminate mechanisms for this relationship and perhaps will point to methods of disease prevention or treatment.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by the NIH Academic Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology Training Grant #AR007304 to J.C.B. and NIH/NIIAMS grants R13—AR04884, AR052000, and AR043052 to N.E.L. We thank Dr Julia Charles for her helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gabriel SE, Michaud K. Epidemiological studies in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and comorbidity of the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:229. doi: 10.1186/ar2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray RO. The aetiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol. 1965;38:810–824. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-38-455-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986:20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odding E, Valkenburg HA, Algra D, et al. Associations of radiological osteoarthritis of the hip and knee with locomotor disability in the Rotterdam Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:203–208. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.4.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagenais S, Garbedian S, Wai EK. Systematic review of the prevalence of radiographic primary hip osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:623–637. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0625-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Hochberg MC, et al. Progression of radiographic hip osteoarthritis over eight years in a community sample of elderly white women. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1477–1486. doi: 10.1002/art.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawrence RC, Hochberg MC, Kelsey JL, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of selected arthritic and musculoskeletal diseases in the United States. J Rheumatol. 1989;16:427–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson AE, Braga L, Renner JB, et al. Characterization of individual radiographic features of hip osteoarthritis in African American and White women and men: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 62:190–197. doi: 10.1002/acr.20067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tepper S, Hochberg MC. Factors associated with hip osteoarthritis: data from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES-I) Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1081–1088. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nevitt MC, Xu L, Zhang Y, et al. Very low prevalence of hip osteoarthritis among Chinese elderly in Beijing, China, compared with whites in the United States: the Beijing osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1773–1779. doi: 10.1002/art.10332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Issa SN, Sharma L. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: an update. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8:7–15. doi: 10.1007/s11926-006-0019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birrell F, Lunt M, Macfarlane G, et al. Association between pain in the hip region and radiographic changes of osteoarthritis: results from a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:337–341. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seifert MH, Whiteside CG, Savage O. A 5-year follow-up of fifty cases of idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis. 1969;28:325–326. doi: 10.1136/ard.28.3.325-c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright AA, Cook C, Abbott JH. Variables associated with the progression of hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:925–936. doi: 10.1002/art.24641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waarsing JH, Rozendaal RM, Verhaar JA, et al. A statistical model of shape and density of the proximal femur in relation to radiological and clinical OA of the hip. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.02.003. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkins JM, Loughlin J, Snelling SJB. Osteoarthritis genetics: current status and future prospects. Future Rheumatol. 2007;2:607–620. [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacGregor AJ, Antoniades L, Matson M, et al. The genetic contribution to radiographic hip osteoarthritis in women: results of a classic twin study. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2410–2416. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2410::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spector TD, Cicuttini F, Baker J, et al. Genetic influences on osteoarthritis in women: a twin study. Br Med J. 1996;312:940–943. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7036.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valdes AM, Spector TD. The contribution of genes to osteoarthritis. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:45–66. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.08.007. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loughlin J, Sinsheimer JS, Carr A, et al. The CALM1 core promoter polymorphism is not associated with hip osteoarthritis in a United Kingdom Caucasian population. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meulenbelt I, Min JL, Bos S, et al. Identification of DIO2 as a new susceptibility locus for symptomatic osteoarthritis. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1867–1875. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mototani H, Mabuchi A, Saito S, et al. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism in the core promoter region of CALM1 is associated with hip osteoarthritis in Japanese. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1009–1017. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forster T, Chapman K, Loughlin J. Common variants within the interleukin 4 receptor alpha gene (IL4R) are associated with susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Hum Genet. 2004;114:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kizawa H, Kou I, Iida A, et al. An aspartic acid repeat polymorphism in asporin inhibits chondrogenesis and increases susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Nat Genet. 2005;37:138–144. doi: 10.1038/ng1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Limer KL, Tosh K, Bujac SR, et al. Attempt to replicate published genetic associations in a large, well defined osteoarthritis case-control population (the GOAL study) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meulenbelt I, Seymour AB, Nieuwland M, et al. Association of the interleukin-1 gene cluster with radiographic signs of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1179–1186. doi: 10.1002/art.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millward-Sadler SJ, Khan NS, Bracher MG, et al. Roles for the interleukin-4 receptor and associated JAK/STAT proteins in human articular chondrocyte mechanotransduction. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moxley G, Meulenbelt I, Chapman K, et al. Interleukin-1 region meta-analysis with osteoarthritis phenotypes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustafa Z, Dowling B, Chapman K, et al. Investigating the aspartic acid (D) repeat of asporin as a risk factor for osteoarthritis in a UK Caucasian population. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3502–3506. doi: 10.1002/art.21399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pola E, Papaleo P, Pola R, et al. Interleukin-6 gene polymorphism and risk of osteoarthritis of the hip: a case-control study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:1025–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poree B, Kypriotou M, Chadjichristos C, et al. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and/or soluble IL-6 receptor down-regulation of human type II collagen gene expression in articular chondrocytes requires a decrease of Sp1.Sp3 ratio and of the binding activity of both factors to the COL2A1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4850–4865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura Y, Nawata M, Wakitani S. Expression profiles and functional analyses of Wnt-related genes in human joint disorders. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:97–105. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62957-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Southam L, Dowling B, Ferreira A, et al. Microsatellite association mapping of a primary osteoarthritis susceptibility locus on chromosome 6p12.3-q13. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3910–3914. doi: 10.1002/art.20634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkins JM, Southam L, Mustafa Z, et al. Association of a functional microsatellite within intron 1 of the BMP5 gene with susceptibility to osteoarthritis. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerkhof JM, Uitterlinden AG, Valdes AM, et al. Radiographic osteoarthritis at three joint sites and FRZB, LRP5, and LRP6 polymorphisms in two population- based cohorts. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:1141–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Min JL, Meulenbelt I, Riyazi N, et al. Association of the Frizzled-related protein gene with symptomatic osteoarthritis at multiple sites. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1077–1080. doi: 10.1002/art.20993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodriguez-Lopez J, Pombo-Suarez M, Liz M, et al. Further evidence of the role of frizzled-related protein gene polymorphisms in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1052–1055. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lane NE, Lin P, Christiansen L, et al. Association of mild acetabular dysplasia with an increased risk of incident hip osteoarthritis in elderly white women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:400–404. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<400::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner S, Hofstetter W, Chiquet M, et al. Early osteoarthritic changes of human femoral head cartilage subsequent to femoro-acetabular impingement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:508–518. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grotle M, Hagen KB, Natvig B, et al. Obesity and osteoarthritis in knee, hip and/or hand: an epidemiological study in the general population with 10 years follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:132. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saville PD, Dickson J. Age and weight in osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1968;11:635–644. doi: 10.1002/art.1780110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spector TD. The fat on the joint: osteoarthritis and obesity. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:283–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heliovaara M, Makela M, Impivaara O, et al. Association of overweight, trauma and workload with coxarthrosis: a health survey of 7,217 persons. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:513–518. doi: 10.3109/17453679308993681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felson DT. Epidemiology of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Epidemiol Rev. 1988;10:1–28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doherty M, Courtney P, Doherty S, et al. Nonspherical femoral head shape (pistol grip deformity), neck shaft angle, and risk of hip osteoarthritis: a case-control study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3172–3182. doi: 10.1002/art.23939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodman DA, Feighan JE, Smith AD, et al. Subclinical slipped capital femoral epiphysis: relationship to osteoarthrosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1489–1497. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Javaid MK, Lane NE, Mackey DC, et al. Changes in proximal femoral mineral geometry precede the onset of radiographic hip osteoarthritis: the study of osteoporotic fractures. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2028–2036. doi: 10.1002/art.24639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arokoski JP, Arokoski MH, Jurvelin JS, et al. Increased bone mineral content and bone size in the femoral neck of men with hip osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:145–150. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reikeras O, Hoiseth A. Femoral neck angles in osteoarthritis of the hip. Acta Orthop Scand. 1982;53:781–784. doi: 10.3109/17453678208992292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mills HJ, Horne JG, Purdie GL. The relationship between proximal femoral anatomy and osteoarthrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993:205–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore RJ, Fazzalari NL, Manthey BA, et al. The relationship between head-neck-shaft angle, calcar width, articular cartilage thickness and bone volume in arthrosis of the hip. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:432–436. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.5.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gregory JS, Waarsing JH, Day J, et al. Early identification of radiographic osteoarthritis of the hip using an active shape model to quantify changes in bone morphometric features: can hip shape tell us anything about the progression of osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3634–3643. doi: 10.1002/art.22982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gregory JS, Testi D, Stewart A, et al. A method for assessment of the shape of the proximal femur and its relationship to osteoporotic hip fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:5–11. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cootes TF, Taylor CJ, Cooper DH, et al. Active shape models: their training and application. Computer Vision and Image Understanding. 1995;61:38–59. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witte F, Dokas J, Neuendorf F, et al. Comprehensive expression analysis of all Wnt genes and their major secreted antagonists during mouse limb development and cartilage differentiation. Gene Expr Patterns. 2009;9:215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon-Chazottes D, Tutois S, Kuehn M, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the low-density lipoprotein receptor LRP4 cause abnormal limb development in the mouse. Genomics. 2006;87:673–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corr M. Wnt-beta-catenin signaling in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:550–556. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lane NE, Lian K, Nevitt MC, et al. Frizzled-related protein variants are risk factors for hip osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1246–1254. doi: 10.1002/art.21673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lories RJ, Peeters J, Bakker A, et al. Articular cartilage and biomechanical properties of the long bones in Frzb-knockout mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:4095–4103. doi: 10.1002/art.23137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Loughlin J, Dowling B, Chapman K, et al. Functional variants within the secreted frizzled-related protein 3 gene are associated with hip osteoarthritis in females. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9757–9762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403456101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Velasco J, Zarrabeitia MT, Prieto JR, et al. Wnt pathway genes in osteoporosis and osteoarthritis: differential expression and genetic association study. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0931-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gavriatopoulou M, Dimopoulos MA, Christoulas D, et al. Dickkopf-1: a suitable target for the management of myeloma bone disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:839–848. doi: 10.1517/14728220903025770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li X, Ominsky MS, Warmington KS, et al. Sclerostin antibody treatment increases bone formation, bone mass, and bone strength in a rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:578–588. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lories RJ, Luyten FP. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling in joint homeostasis and disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takahara M, Harada M, Guan D, et al. Developmental failure of phalanges in the absence of growth/differentiation factor 5. Bone. 2004;35:1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Storm EE, Kingsley DM. GDF5 coordinates bone and joint formation during digit development. Dev Biol. 1999;209:11–27. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duprez D, Bell EJ, Richardson MK, et al. Overexpression of BMP-2 and BMP-4 alters the size and shape of developing skeletal elements in the chick limb. Mech Dev. 1996;57:145–157. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Southam L, Rodriguez-Lopez J, Wilkins JM, et al. An SNP in the 5’-UTR of GDF5 is associated with osteoarthritis susceptibility in Europeans and with in vivo differences in allelic expression in articular cartilage. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2226–2232. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyamoto Y, Mabuchi A, Shi D, et al. A functional polymorphism in the 5′ UTR of GDF5 is associated with susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:529–533. doi: 10.1038/2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wagner EF, Karsenty G. Genetic control of skeletal development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:527–532. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bullough PG. The role of joint architecture in the etiology of arthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(Suppl A):S2–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gelber AC, Hochberg MC, Mead LA, et al. Joint injury in young adults and risk for subsequent knee and hip osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:321–328. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-5-200009050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Croft P, Coggon D, Cruddas M, et al. Osteoarthritis of the hip: an occupational disease in farmers. Br Med J. 1992;304:1269–1272. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6837.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vingard E, Alfredsson L, Goldie I, et al. Sports and osteoarthrosis of the hip: an epidemiologic study. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:195–200. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Lane NE, et al. Association of estrogen replacement therapy with the risk of osteoarthritis of the hip in elderly white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2073–2080. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reijman M, Hazes JM, Pols HA, et al. Acetabular dysplasia predicts incident osteoarthritis of the hip: the Rotterdam study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:787–793. doi: 10.1002/art.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okano K, Enomoto H, Osaki M, et al. Outcome of rotational acetabular osteotomy for early hip osteoarthritis secondary to dysplasia related to femoral head shape: 49 hips followed for 10–17 years. ActaOrthop. 2008;79:12–17. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stulberg SD, Cooperman DR, Wallensten R. The natural history of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:1095–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hoaglund FT, Shiba R, Newberg AH, et al. Diseases of the hip: a comparative study of Japanese Oriental and American white patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1376–1383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakamura S, Ninomiya S, Nakamura T. Primary osteoarthritis of the hip joint in Japan. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989:190–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Soballe K, et al. Hip dysplasia and osteoarthrosis: a survey of 4151 subjects from the Osteoarthrosis Substudy of the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:149–158. doi: 10.1080/00016470510030517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stulberg SD, Cordell LD, Harris WH, et al. Unrecognised childhood hip disease: a major cause of idiopathic osteoarthritis of the hip. Hip. 1975;3:212–230. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Giori NJ, Trousdale RT. Acetabular retroversion is associated with osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003:263–269. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093014.90435.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lynch JA, Parimi N, Chaganti RK, et al. The association of proximal femoral shape and incident radiographic hip OA in elderly women. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:1313–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]