Abstract

The sigma-1 receptor (Sig-1R) is an endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein that involves a wide range of physiological functions. The Sig-1R has been shown to bind psychostimulants including cocaine and methamphetamine (METH) and thus has been implicated in the actions of those psychostimulants. For example, it has been demonstrated that the Sig-1R antagonists mitigate certain behavioral and cellular effects of psychostimulants including hyperactivity and neurotoxicity. Thus, the Sig-1R has become a potential therapeutic target of medication development against drug abuse that differs from traditional monoamine-related strategies. In this review, we will focus on the molecular mechanisms of the Sig-1R and discuss in such a manner with a hope to further understand or unveil unexplored relations between the Sig-1R and the actions of cocaine and METH, particularly in the context of cellular biological relevance.

Introduction

The History of Sigma Receptors

Sigma receptors were first identified from the behavioral and pharmacological studies, and were suggested as a subtype of opioid receptors known as the “sigma opioid receptor” [1]. Martin et al. proposed that three distinguishable receptors (mu, kappa and sigma receptors) contribute to distinct symptomatology induced by opioids. Since the prototypic sigma agonist, (+)SKF-10,047, produced hallucinogenic effects, sigma receptors were believed to specifically mediate the psychotomimetic effects of opioids. Later studies however indicated that the sigma receptor has certain features that distinguish it from other opioid receptors: (1) The SKF-10,047 binding protein has different stereospecificity from that of other opioid receptors (i.e., affinity at sigma receptors: dextrorotatory isomer > levorotatory; at opioid receptors: levorotatory > dextrorotatory ); (2) The (+)SKF-10,047 binding protein has very low affinity for opioid antagonists such as naloxone and naltrexone [2, 3]; (3) Naltrexone does not antagonize SKF-10,047-induced behavioral effects [4].

Further studies from ligand binding assays revealed that there are two subtypes of sigma receptors, sigma-1 and sigma-2 [5–9]. Sigma-2 receptor (Sig-2R) has a reversed stereoselectivity ( levorotatory > dextrorotatory ) for sigma ligands such as SKF-10,047 and pentazocine from that of sigma-1 receptor (Sig-1R). The existence of Sig-1R and Sig-2R was strongly supported by the evidence from photo-affinity labeling studies which showed that the Sig-1R and the Sig-2R consist of 25 kDa and 18–21.5 kDa polypeptides, respectively [8–10]. The Sig-1R has been cloned and the sequence shows no significant homology with that of any of other mammalian proteins including opioid receptors [11]. At present it is recognized that the Sig-1R is a non-opioid, non-G protein-coupled intracellular receptor comprised of a 24 kD single protein [12–14]. On the other hand, the Sig-2R has not yet been cloned. Although Xu et al. identified the Sig-2R as the progesterone receptor membrane component 1:PGRMC1 [15], there exists certain controversy regarding, for instance, its molecular size which seems to be different from that of the Sig-2R. Further, the Sig-2R could still be specifically photo-affinity labeled in the PGRMC1 knockout cells [16–18].

Physiological Functions of Sigma Receptors

Sigma receptors are expressed ubiquitously throughout many organs [9, 11, 13, 19–24]. The functions of Sig-1R have been intensely investigated especially in the central nervous system (CNS). The Sig-1R has been implicated in neuropsychiatric diseases [25, 26] such as depression [27], anxiety and schizophrenia [28], partly because the Sig-1R binds to many psychotomimetic and psychiatric drugs. In addition, it has been suggested that the Sig-1R promotes a positive effect on memory and learning processes [29, 30]. Also, the Sig-1R seems to be neuroprotective in nature [31] and thus plays a role in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease [32], Parkinson’s disease, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and strokes [33, 34]. Interestingly, because clinically available drugs for those psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders are quite limited, the Sig-1R ligands are being explored to serve as new therapeutic agents for those diseases. In addition, the involvement of the Sig-1R in cancer, immune system, neuropathic pain [35], cardiac functions [36] and retinal disease have been reported. Regarding the Sig-2R, studies on its specific functions have been difficult partly because of the low selectivity of ligands and because of the lack of information on its sequence. Nevertheless, as highly selective ligands for Sig-2R are being developed, there is a strong notion that the Sig-2R relates to cancer. For example, the Sig-2R expression is dramatically elevated in various tumor cells and Sig-2R agonists cause apoptosis and tumor cell death [37–39]. The Sig-2R has thus been recently receiving more attention as a potential biomarker of proliferation [37, 40, 41]. It also has been suggested that Sig-2R ligands possess antidepressant-like effects [42] and may also attenuate the learning impairment [30].

Drug Abuse and Sigma Receptors

Sigma receptors have been implicated in the addictive process and toxicity induced by psychostimulants. Cocaine and methamphetamine (METH) have been mostly studied in this regard because cocaine and METH bind to the Sig-1R at physiologically relevant concentrations [43–54] (cocaine at 2–7 μM, METH at 2–4 μM), however, to the Sig-2R with lower affinities (cocaine at 19–31 μM and METH at 16–47 μM) [55–59] (Table 1 and 2). Also, cocaine and METH are among the most abused substances in the world, and currently effective medications are lacking against the addiction and toxicity of those two drugs. Therefore, sigma receptors and associated ligands have been explored as therapeutic targets against cocaine and METH.

Table 1.

Affinity of cocaine and methamphetamine (METH) at sigma-1 receptor (Sig-1R) and sigma-2 receptor (Sig-2R)

| Sample/Reference | Affinity for Sig-1R | Affinity for Sig-2R | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine | Rat cerebellum, [59] | 6.7 ± 0.3 μM*1 | |

| Mouse brain, [56] | 2 ± 0.2 μM*2 | 31 ± 4 μM*3 | |

| Guinea pig brain minus cerebellum, [57] | 5190 (3800–7060) nM*2 | 19,300 (16,000–23,300) nM*3 | |

| METH | Rat brain, [55] | 2.16 ± 0.25 μM*2 | 46.67 ± 10.34 μM*3 |

| Guinea pig brain minus cerebellum, [58] | 4390 (3740–5160) nM*2 | 15,900 (11,700–21,500) nM*3 |

in competition with Haloperidol

in competition with (+)-Pentazocine

in competition with DTG in the presence of (+)-Pentazocine

Table 2.

Peak concentrations of cocaine and methamphetamine (METH) in the blood, plasma, or brain

| Drug administrating condition/Reference | Blood or Plasma | Brain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute cocaine | Mouse, 10 mg/kg, ip, [46] | 0.75 μg/ml | 2.6 μg/g |

| Mouse, 25 mg/kg, ip, [46] | 1.5 μg/ml | 6.7 μg/g | |

| Rat, 8 mg/kg, iv, [44,45] | 0.61 ± 0.06 μg/ml | 7.27 ± 0.18 μg/g | |

| Rat, 20 mg/kg, sc, [44,45] | 0.49 ± 0.06 μg/ml | 3.44 ± 0.36 μg/g | |

| Rat, 30 mg/kg, ip, [43] | 2.7 μM | 1.41 ± 0.09 μM* | |

| Chronic cocaine | Rat, 20 mg/kg, sc for 3 weeks, twice a day, [44] | 0.50 ± 0.10 μg/ml | 3.05 ± 0.14 μg/g |

| Rat, 10–20 mg/kg, sc for 10 or 30 days, once a day, | 10 days, 4.1 μM | 10 days, 2.62 μM* | |

| 30 mg/kg, ip on the test day, [43] | 30 days, 5.5 μM | 30 days, 1.8 μM* | |

| Human, 20.5 mg, iv, [48] | 180 ± 56 ng/ml | ||

| Human, 94.6 mg, ni, [48] | 220 ± 50 ng/ml | ||

| Human, 50 mg, si, [48] | 203 ± 88 ng/ml | ||

| Acute METH | Mouse, 2.5 mg/kg, ip, [47] | 2.63 ± 0.27 μg/g | |

| Mouse, 5.0 mg/kg, ip, [47] | 4.96 ± 0.35 μg/g | ||

| Mouse, 10 mg/kg, ip, [47] | 8.90 ± 0.40 μg/g | ||

| Rat, 1 mg/kg, sc, [51] | 7.5 ng/ml | 70 ng/g | |

| Rat, 5 mg/kg, sc, [51] | 40 ng/ml | 300 ng/g | |

| Rat, 0.5 mg/kg, iv, [52] | 0.54 ± 0.07 μM | ||

| Rat, 2.5 mg/kg, iv, [54] | 1.0 ± 0.1 μg/ml | ||

| Chronic METH | Rhesus monkey, 0.32 mg/kg, im, [53] | 51.0 ± 8.5 ng/ml | |

| Human, 30 mg, iv, [50] | 175 ng/ml | ||

| Human, 15.5 mg, iv, [49] | 100 ng/ml |

Extracellular concentrations in the nucleus accumbens

Cocaine is most likely an agonist for the Sig-1R since the cocaine effects are blocked by Sig-1R antagonists. In contrast, Sig-1R agonists often mimic or potentiate the effect of cocaine. METH possibly acts like an agonist at the Sig-1R for the same reasons as cocaine does. However, METH seemingly acts like an inverse agonist in the Sig-1R-Bip association test (see Section 2, Molecular chaperon activity and the ligand effects). The exact biochemical relation between METH and the Sig-1R remains to be totally clarified.

Interestingly, subtype non-selective sigma receptor antagonists are often more effective in inhibiting the METH effects, suggesting that there may be some unknown synergistic relation between Sig-1R and Sig-2R. In fact, a number of pharmacological studies have demonstrated that antagonists of sigma receptors, mostly Sig-1R-preferring only or non-selective for Sig1R and Sig-2R, attenuate the effects of cocaine and METH in rodents. For example, pretreatment with selective Sig-1R antagonists attenuates hyperactivity, behavioral sensitization, and conditioned place preference (CPP) induced by cocaine, and the locomotor hyperactivity stimulated by METH. Also, Sig-1R selective antagonists mitigate cellular and behavioral toxicities induced by cocaine including convulsion and death while non-selective antagonists counteract METH-induced neuronal degeneration [60–62]. In general, specific involvement of the Sig-2R in this regard has just begun to be understood. For example, a selective Sig-2R antagonist counteracts cocaine-mediated locomotion activity [63]. However, the precise molecular mechanisms between the actions of those two abused drugs and the roles of sigma receptors are not fully understood.

Since the sequence of the Sig-1R is known and some progresses for understanding the Sig-1R’s molecular functions have been made, this review will focus on the Sig-1R and the associated molecular mechanisms. At first we will provide the biological information on Sig-1R, and then discuss the molecular basis of the Sig-1R as it relates to the actions of cocaine and METH including in particular the addictive process and toxicity.

Biology of the Sigma-1 Receptor

Structure and Ligand Binding

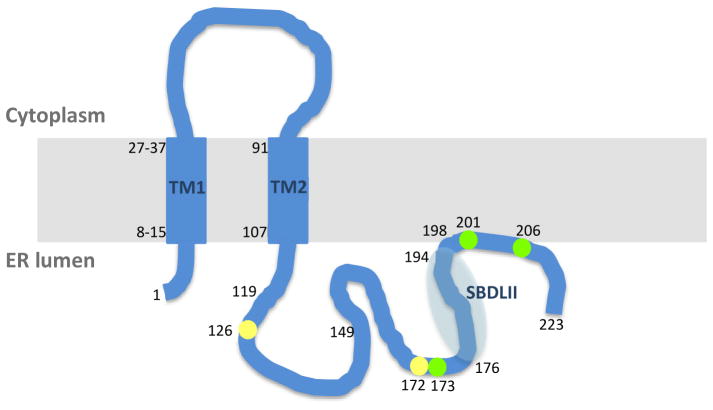

The Sig-1R is a 223 amino acid (a.a.) transmembrane protein that possesses two transmembrane domains (TMs), one at the N-terminus (TM1: predicted as an about 20 a.a. spanning between residues 8~15 and 27~37) and the other at the center (TM2: a.a. residues 91–107, also referred as sterol-binding domain like-I (SBDLI) [64]). A membrane-attached region at the C-terminus (a.a. residues 198–206) was suggested from solution NMR studies [13, 65–67] (Figure 1). The Sig-1R protein is highly conserved in various mammalian species with over 90% of similarity in the a.a. sequence [19]. The Sig-1R shared no homology with any of other mammalian proteins, but shares a 30% homology with a yeast C7–C8 sterol isomerase [11]. The homology resides mainly between the sterol-binding pocket of the C7–C8 sterol isomerase and TM2, and a hydrophobic region (a.a. residues 176–194, referred as SBDLII in [64]) at the C-terminus of Sig-1R[11]. The homology, though limited, suggests that the Sig-1R has affinity for sterols [68]. Palmer et al. examined the Sig-1R-cholesterol interaction and found that tyrosines 173, 201 and 206 play a critical role for the Sig-1R to bind cholesterol [69]. Several sterols and lipids have been proposed as endogenous ligands of Sig-1R. A number of studies showed that progesterone binds to Sig-1R and competes with sigma ligands at the physiologically relevant concentrations [68], suggesting certain functionalities in vivo [70]. By using the unique property of sigma ligands in which agonists enhance the action of NMDA receptor while antagonists, being devoid of effect by themselves, block the effect caused by agonists, Bergeron et al. proposed progesterone as an antagonist and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) as an agonist at the Sig-1R [71]. In addition, sphingosine [72], monoglycosylated ceramide [73], 25-dehydroxycholesterol [74] and myristic acid [75] have been shown to have high affinities for the Sig-1R. Further studies are needed to clarify the physiological and functional relevance of the Sig-1R-lipid interaction except for the Sig-1R-myristic acid interaction which has been shown to play a critical role in axon elongation [75].

Figure 1. A schematic presentation of predicted topology and ligand binding regions of sigma-1 receptor (Sig-1R).

The numbers represent amino acid (a.a.) residues. The colored circles show the a.a. residues critical for Sig-1R binding to haloperidol (yellow) and cholesterol (green), respectively. The TM2 and SBDLII are suggested to compose the ligand binding region of Sig-1R. A splice variant of Sig-1R, which lacks a.a. 119–149 region, is devoid of ligand binding. Abbreviations: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; TM, transmembrane domain; SBDLII, sterol-binding domain like-II

Photo-affinity labeling studies combined with biochemical approaches have revealed that TM2 and SBDLII are juxtaposed to form, at least in part, the Sig-1R ligand binding region because point mutation in TM2 causes a decrease of the ligand binding ability [76]. The possibility exists that TM1 is also in the proximity to SBDLII and contributes thus to the binding of ligands [77]. A splice variant of Sig-1R, which lacks a.a. residues 119–149, was found to be nonfunctional in the ligand binding assay in a Jurkat human T-lymphocyte cell line [78], suggesting that the C-terminal region following TM2 is important for the ligand binding to Sig-1R. Seth et al. reported two essential a.a. residues, Asp126 and Glu172 for the haloperidol binding to Sig-1R [24]. Since TM2 and SBDLII are hydrophobic in nature, it is reasonable to assume the hydrophobicity somehow contributes to the binding between lipids, or otherwise hydrophobic part(s) of sigma ligands, and the Sig-1R. Additionally, the negative charge of anionic a.a. including Asp126 and Glu172 between TM2 and SBDLII is possibly utilized by the Sig-1R to interact with sigma ligands that are positively charged. The positively charged hallucinogen N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) apparently functions at least in part through Sig-1R even though the affinity of DMT at Sig-1R is in the micromolar range [79]. In contrast to that seen in wild type mice, Sig-1R knockout mice failed to respond behaviorally to DMT [66].

Molecular Chaperone Activity and the Ligand Effects

It has been demonstrated that the C-terminus of Sig-1R has a chaperone activity that assists proteins to fold properly to ensure their functionality. The Sig-1R is a unique chaperone in that it consists of two transmembrane domains and that it is a ligand-regulated chaperone. The second transmembrane domain, in addition to being important in ligand binding, apparently plays an important role in Sig-1R interaction with other transmembrane proteins [74, 80]. Because the Sig-1R chaperone, being a transmembrane itself, tends to interact more with other transmembrane proteins including many ion channels and receptors, it is tempting to speculate that this cross-interaction between transmembrane regions of a chaperone and its client protein may have an as-yet-unknown special significance in the action of the Sig-1R as a chaperone. Further studies are required to clarify this seemingly important speculation.

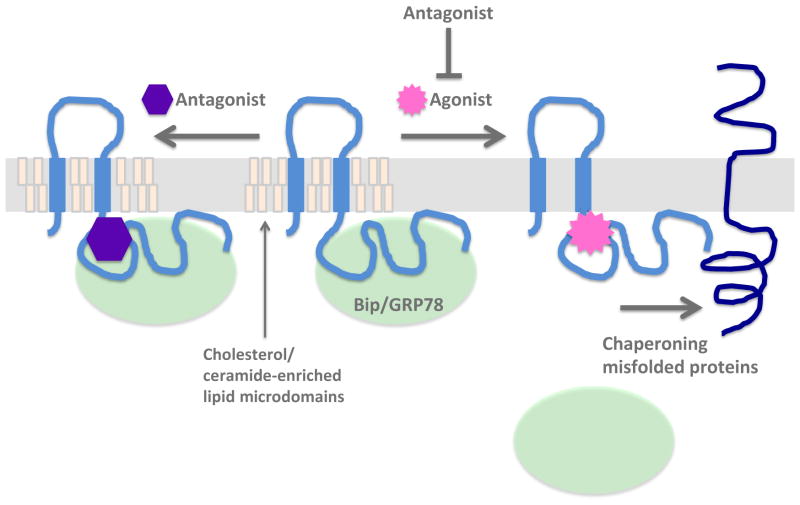

At the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the C-terminus of Sig-1R faces the ER lumen and interacts with another chaperone protein Bip/GRP78 [13]. The Sig-1R interaction with Bip/GRP78 prevents the Sig-1R’s chaperone activity. Sigma agonists cause the dissociation of Bip/GRP78 from the Sig-1R, resulting in the unleashing of the chaperone activity of the Sig-1R. Sigma antagonists inhibit the agonist’s effect on the Sig-1R-Bip/GRP78 interaction (Figure 2). Although the Sig-1R is implicated in a wide variety of physiological functions, how and why those functions specifically relate to the chaperone activity of the Sig-1R remains to be fully understood. The detailed molecular functions of Sig-1R as a chaperone will be discussed later.

Figure 2. Sigma-1 receptor (Sig-1R) chaperone activity and the ligand effects.

Sig-1R resides at the MAM which is enriched in cholesterol and ceramide. Sig-1R physically associates with Bip/GRP78 which inhibits the Sig-1R’s chaperone activity. Upon stimulation by agonists, Sig-1R dissociates from Bip/GRP78 and chaperones misfolded proteins. Antagonists by themselves do not disrupt the interaction between Sig-1R and Bip/GRP78 but, if pre-treated before agonists, can block the Sig-1R-BiP dissociation caused by the agonist.

Intracellular Localization of Sig-1R

The Sig-1R predominantly localizes in the ER where all of the transmembrane proteins as well as lipids for most of cellular organelles are produced. The Sig-1R is concentrated especially in the mitochondria-associated ER membrane (MAM). The MAM is a dynamic lipid-raft like domain in the ER which is enriched in cholesterol and ceramides and is thus different from a normal ER membrane [73, 81]. The interaction with lipids such as cholesterol and ceramides may be important for the Sig-1R to localize at the MAM since cholesterol or ceramide depletion from lipid raft causes a decreased partitioning of the Sig-1R at the MAM.

The MAM enables metabolites and signaling molecules to exchange between the ER and mitochondria. The exchange plays a crucial role in various cellular functions of physiological and pathological significance [82]. It has been established that the MAM is the central location to regulate lipid transfer and rapid transmission of Ca2+ signaling between the ER and mitochondria, the latter serving to enhance the mitochondrial bioenergetics [83]. Additionally, the MAM is beginning to be understood as having a role in energy metabolism, cellular survival, redox status, ER stress, autophagy and inflammasome signaling [84]. Recent studies elucidating new molecular functions of Sig-1R are closely paying attention the cellular events at the MAM. In particular, the Sig-1R might contribute to the formation of the MAM [85, 86].

Although the detailed mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated, it is believed that the Sig-1R subcellular localization is dynamically changed when cells or neurons are stimulated with Sig-1R agonists or are under cellular stress. The mobilized Sig-1R can translocate from the ER to its contiguous structures including the nuclear envelope, subplasmalemmal ER, and even into the plasma membrane. In fact, the existence of the Sig-1R at the plasma membrane has been shown by using biochemical methods in the Sig-1R- transfected cells [87, 88]. On the other hand, immuno-electron microscopy studies indicate that the endogenous Sig-1R is present at the subplasmalemmal ER but not at the plasma membrane as seen in motor neurons and retinal neurons [89, 90]. A number of studies suggest that the Sig-1R modulate functions of plasma membrane proteins such as ion channels and G protein-coupled receptor through the direct protein-protein interaction. Given what we just discussed above, it can be envisioned that there are two possible ways that the Sig-1R can regulate target proteins at the plasma membrane: (1) Sig-1R and target proteins are both present at the plasma membrane and can interact with each other; (2) The Sig-1R at the subplasmalemmal ER can interact with target proteins at the plasma membrane via close proximity. There is also the possibility that the Sig-1R may interact with target proteins at the ER, leading to affecting the target protein’s function at the plasma membrane. Further studies may clarify the dynamics of the Sig-1R as it relates to its interaction with other target proteins and their resultant subcellular localization.

Sig-1R-related Molecular Mechanisms and the Actions of Cocaine and Methamphetamine

Cocaine and Methamphetamine

It is widely believed that cocaine and amphetamine-like psychostimulants including METH produce the rewarding effect by increasing dopamine (DA) transmission in the limbic system, especially in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and prefrontal cortex (PFC), both relating to the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the brain. The resultant activation of the dopamine receptors is also involved in the rewarding effect. However, the dynamic downstream consequences are not fully understood. In addition, establishing an addictive process apparently involves other dopamine-independent pathway(s).

It has been well known that METH causes damage and degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in various brain regions including striatum through various processes such as the activation of DA receptors, oxidative and ER stress, and inflammation. The dopaminergic neuronal damage induced by METH is implicated in psychosis, memory impairment, and motor defects. Indeed, it has been suggested that the neurodegeneration-related changes and abnormality in morphology in substantia nigra seen in METH abusers are associated with increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease that results from loss of dopaminergic neurons. It has been also reported that METH causes neurotoxicity to other types of neurons including serotonergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic, and cholinergic neurons, suggesting that interactions between dopaminergic and the other neurotransmitter systems affects the behavioral and neuronal responses to METH.

Regulation of Intracellular Ca2+ Concentration via IP3Rs

Ca2+ is an intracellular second messenger controlling several cellular events. The intracellular Ca2+ concentration is tightly regulated from Ca2+ sources at the extracellular space and at the intracellular Ca2+ stores including ER and mitochondria. Ca2+ in the ER lumen is released via inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptors (IP3Rs), ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and polycystin-2 [91]. The Sig-1R has been shown to be involved in IP3Rs-mediated regulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ((Ca2+)i). There are three different isoforms of IP3Rs: type1 (IP3R1), type2 (IP3R2) and type3 (IP3R3). A predominant isoform usually exists in particular cellular types, e.g. IP3R1 in neurons, IP3R2 in liver and heart, and IP3R3 in cultured cells. However, most types of cells express two or all of the three isoforms [92].

The Sig-1R agonist was reported to enhance bradykinin-induced elevation of (Ca2+)i most likely via IP3/IP3R3, which is in turn inhibited by the Sig-1R antagonist in neuroblastoma/glioma hybrid NG108 cells [93, 94]. Later, it was demonstrated that the Sig-1R and IP3R3 are both enriched at the MAM where the Sig-1R stabilizes IP3R3 when cells were either under ER stress due to the ER Ca2+ depletion or being stimulated by Sig-1R agonists; leading thus to the potentiation of Ca2+ transmission from ER to mitochondria [13].

While the IP3R3 has been proved as a client of the Sig-1R chaperone, it remains less clear if IP3R1 and IP3R2 are also chaperoned by the Sig-1R. Nevertheless, there are reports supporting the possibility that IP3R1 and IP3R2 are also clients of the Sig-1R chaperone. IP3R1 is enriched at the MAM in other cell types including HeLa cells and the rat liver tissue lysate [95]. As well, the Sig-1R is co-immunoprecipitated with IP3R1 in hepatocytes [96]. In the heart, IP3R2 contributes to the Ca2+ influx into mitochondria and the Sig1R is physically associated with IP3R2. Interestingly, the Sig-1R stimulation by the agonists ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction through the enhancement of the Sig-1R-IP3R2 interaction and by restoring the IP3R2-mediated Ca2+ mobilization from the ER into the mitochondria and the resultant mitochondrial ATP production [97, 98]. Recently, it was suggested that the RyR is involved in the cardiac protective effects of Sig-1R agonists [98, 99]. Therefore, the Sig-1R may regulate a variety of intracellular Ca2+ channels operated through both IP3Rs and RyRs, depending on the types of cells as well as the expression patterns of IP3R and RyR isoforms.

In agreement with previous studies [93, 94], Barr et al. recently indicated that cocaine potentiates (Ca2+)i elevation through IP3Rs that are activated by inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in dopamine D1 receptor (D1R) positive neurons in the NAc. The report showed that this effect of cocaine is not related to the extracellular Ca2+ [100]. This effect of cocaine is IP3R specific and not related to RyRs, which is abolished by pretreatment with Sig-1R antagonists. Further, cocaine alone did not cause the elevation of (Ca2+)i. Interestingly, indirect activation of D1R by cocaine and amphetamine have been shown to augment IP3 levels in the striatum via phospholipase C [101]. Also, overexpression of Sig-1R promotes mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and ATP production [85]. In the study [100], cocaine was microinjected into cytoplasm, suggesting that cocaine directly activates the intracellular Sig-1R that stabilizes the IP3R function likely by chaperoning and causes thus the augmentation of ATP production. It was also showed that the increase of (Ca2+)i triggers activation of transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels that allow for the activation of D1R positive neurons. Cocaine enhances the IP3Rs/TRPC-dependent depolarization through the Sig-1R and this pathway likely is involved in the cocaine-induced hyperactivity and sensitization since the cocaine effects are attenuated by pretreatment with the TRPC or Sig-1R inhibitor.

Recent studies suggest the involvement of IP3Rs in the development of drug dependence. IP3Rs antagonists dose-dependently inhibit the CPP induced by cocaine and METH. The IP3R1 expression level is elevated in the NAc of mice conditioned with those drugs. Further the elevated IP3R1 is abolished by the selective antagonist for D1R or dopamine D2 receptors (D2R) [102, 103]. One underlying mechanism for the upregulation of the IP3R1 expression is that stimulation of D1R and D2R, respectively, activates AP-1/NFATc4-dependent IP3R1 gene transcription [104, 105]. This DA-dependent elevation of IP3R1 expression apparently is a key step to develop CPP induced by cocaine and METH.

Taken together, the above results suggest that during a CPP test cocaine or METH causes an indirect stimulation of D1R and D2R and the resultant upregulation of IP3R1 expression which may thus lead to the elevation of (Ca2+)i. Interestingly, the Sig-1R mRNA and Sig-1R ligand binding activity in the NAc of cocaine-conditioned mice are concomitantly increased [106, 107]. Thus, cocaine may stimulate the Sig-1R chaperone activity at the ER, leading to the enhancement of the Ca2+ release via IP3Rs and the ultimate increase of ATP in the mitochondria. Sig-1R specific agonists alone are not sufficient to develop CPP. Yet, the DAT inhibitor-induced CPP is attenuated by Sig-1R antagonists [106], suggesting that the DA-dependent upregulation of IP3R1 might be critical for the Sig-1R’s role in the acquisition of drug-induced CPP. Involvement of Sig-1R, IP3Rs and D1R in the acquisition of CPP induced by cocaine is physiologically relevant since the antagonists for those receptors block the CPP [102, 103, 106, 108–110]. The effect of Sig-1R antagonist on METH-induced CPP has not been reported so far.

Regulation of Potassium Channels

It has been documented that repeated cocaine treatment persistently decreases the intrinsic excitability of the NAc medium spiny neurons (MSNs) by increasing the outward K+ current, leading to a long-lasting behavioral sensitization to cocaine. This process is believed to contribute to rewarding effects of cocaine and possibly to the development of the addictive processes to cocaine.

Cocaine-induced increase of K+ current is postulated to be dependent on slowly-inactivating D-type (D-type) and SK type Ca2+-activated (SK) K+ currents. Although modulation of SK channels by Sig-1R agonists has been reported [111], the recent study has clarified that the Sig-1R is involved specifically in the increase of D-type K+ current mediated by chronic cocaine treatment [88]. The Sig-1R modulates D-type K+ current through physical association with Kv1.2, one of K+ channels through physical interaction. Cocaine increases the interaction between Sig-1R and Kv1.2 likely in the plasma membrane due to an increased Kv1.2 in the plasma membrane as a consequence of the activation and translocation of Sig-1R from the ER to the plasma membrane. This possibility is supported by the fact that protein expression levels of Sig-1R and Kv1.2 are not changed. Consistently, the Sig-1R antagonist and knockdown of Sig-1R prevent the cocaine-elicited increase of the D-type K+ current and associated behavioral sensitization [88].

Regulation of Gene Transcription

It has been recognized that cocaine influences gene regulations that affect the neuronal plasticity and behavior. The nuclear envelope comprises two membranes called the inner and outer nuclear membranes and the Sig-1R has been detected in both membranes in retinal neurons [90]. In recent years, it has been revealed that nuclear envelopes play a role in chromatin organization and gene regulation [112]. Results of a recent study [113] demonstrated that the Sig-1R in the nuclear envelope is related to the cocaine-induced gene regulation. Upon cocaine stimulation, the Sig-1R translocates to the nuclear envelope and, as a result, increases the interaction with nuclear envelope integral proteins lamin A/C and emerin. Cocaine intensifies the interactions between emerin, histone deacetylase (HDAC) and barrier-to-auto autointegration factor (BAF) in a Sig-1R-dependent manner. Emerin has been reported to affect epigenetic gene regulation through its binding to HDAC. BAF apparently assists emerin in the tethering of chromatin to the nuclear envelope. Cocaine thus utilizes the Sig-1R to promote the formation of a chromatin remodeling complex consisting of emerin/HDAC/BAF, and enhance its binding to the monoamine oxidase B (MAOB) promoter perhaps near the nuclear envelope. The nuclear periphery, where Sig-1R apparently forms the chromatin-remodeling complex, is somehow regarded as transcriptionally silent [112]. However, the Sig-1R knockdown increases the mRNA expression of MAOB [114] and this effect of the Sig-1R relates to its location and ability at the nuclear envelope [100]. Therefore, the Sig-1R at the nuclear envelope serves as the functional connection between the nuclear envelope and DNA. Thus, the stimulation of the Sig-1R by acute cocaine treatment causes the decreases of the MAOB protein expression via the suppression of the MAOB gene transcription in the prefrontal cortex and NAc in mice [100]. Together, those data indicate that the Sig-1R at the nuclear envelopes plays a role in the cocaine-mediated transcriptional down-regulation of MAOB [113]. The MAOB is a DA degrading enzyme and is possibly involved in behavioral effects of cocaine. In fact, chronic pre-treatment with a MAOB inhibitor prevents the establishment of cocaine self-administration [115]. Further, the MAOB inhibitor suppresses the prolonged behavioral sensitization induced by cocaine during cocaine-withdrawal [113]. However, the temporal pattern of the Sig-1R-related recruitment of chromatin-remodeling factors during the chronic cocaine treatment and after cocaine withdrawal remains to be fully clarified.

Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling

Emerging evidence supports the possibility that the Sig-1R is involved in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). It has been documented that the production of the NADPH-induced ROS is increased in the Sig-1R knockdown neurons [116]. Further, an elevated level of ROS is seen in the retinal Müller cells of Sig-1R knockout (KO) mice when compared to controls [117]. Additionally, the Sig-1R inversely regulates the ROS/ nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB)-dependent pathway. Thus, it was shown that the Sig-1R upregulates the Bcl-2 gene transcription inasmuch as the Bcl-2 transcription is downregulated by the ROS/NFκB pathway [118]. Bcl-2 is a well-characterized anti-apoptotic regulator and is also known to suppress autophagy by inhibiting Beclin1, an autophagy inducing protein [119].

The ROS in cells is generated both in the mitochondria and ER, and the generation of ROS is affected by Ca2+ signaling and the converse is true. As mentioned before, the Sig-1R regulates the Ca2+ release from the ER and its influx to the mitochondria via IP3R3 [13]. As a consequence the Sig-1R may thus affect the mitochondrial ROS production. On the other hand, in Müller cells of Sig-1R KO mice, the expression of Nrf-2 gene, a transcriptional activator for antioxidant proteins, is downregulated, causing thus a decrease in antioxidant proteins such as SOD1, and catalase, as well as xCT that is important for generating the antioxidant glutathione [117]. Another potential mechanism might be related to the Sig-1R-induced downregulation of MAOB. Tyramine, an MAO substrate, induces the production of H2O2, a ROS, which in turn could be inhibited by MAOA or MAOB inhibitor depending on the MAO isoforms expressed in the types of cells [120]. Collectively, the Sig-1R may control the ROS generation by regulating Ca2+ signaling from the ER into the mitochondria, and by regulating genes of ROS modulating factors such as SOD1, catalase, xCT and MAOB. Further studies will be needed to fully elucidate the detailed mechanisms however.

Downstream of the ROS generated from mitochondria, there exists the IRE1 which is one of the ER stress sensors residing specifically at the MAM. Once activated, IRE1 causes the transcriptional upregulation of several ER chaperons in order to counteract the ROS-induced stress. In this mitochondrion-ER-nucleus signaling pathway, it is known that the Sig-1R chaperones IRE1 to maintain its proper folding, thus promoting the cellular survival [80]. Although evidence in terms of the Sig-1R’s direct role in the generation or inhibition of ROS is lacking, indirect evidences mentioned above, including data from the Sig-1R knockdown and KO mice as well as the Sig-1R’s cellular protecting function on the IRE1 downstream of the mitochondrial ROS, suggest that the Sig-1R apparently plays a protective role against the ROS insults under normal physiological conditions.

Previous reports have shown conflicting results regarding the effect of Sig1R agonists and antagonists on the ROS generation. Sig-1R agonists increase the production of ROS and Sig-1R antagonists inhibit the agonist effect in the spinal cord and brain mitochondria [121, 122]. On the other hand, a Sig-1R agonist, (+)-pentazocine, decreases ROS production induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in retinal microglia [123]. Those results suggest that the Sig-1R agonist alone seems to enhance the ROS generation. However, this effect of the Sig-1R agonist may change depending on conditions for example when in the presence of other ROS inducers like LPS.

Yao et al. have indicated that the Sig-1R is directly involved in the cocaine effect on the ROS generation in microglia [124]. They postulated that cocaine induces the ROS generation by hijacking Sig-1Rs to the lipid raft at the plasma membrane and sequentially activating the MAPKs, PI3K/Akt and NFκB pathways. Further, Sig-1R antagonist and knockdown of the Sig-1R attenuate the ROS production and the activation of those pathways. Additionally, this Sig-1R-mediated ROS induction is critical for cocaine to increase the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP1) expression. MCP1 is the key CC chemokine to mediate monocyte-macrophage transmigration across the blood brain barrier (BBB). Consistently, cocaine enhances the monocyte migration into the brain in cocaine treated mice, an effect which is ameliorated by the Sig-1R antagonist. Thus, the Sig-1R-mediated ROS generation may explain at least in part on how cocaine abusers with HIV-1 infection show a BBB disruption and a higher risk of neuroinflammation..

Acute and repeated cocaine have been described to induce the ROS production in the PFC and striatum in rats, an effect which is usually accompanied by increases of antioxidant enzymatic activities [125]. No significant apoptosis is observed probably because the activated antioxidant enzymes counteract the cocaine-induced oxidative stress. A very recent study has indicated that cocaine-induced ROS is involved in cocaine self-administration [126]. Pre and post-treatment of ROS scavengers in the NAc reverses the cocaine self-administration without affecting food intake in rats. The report also found that the oxidative stress is activated mainly in neurons in cocaine self-administering rats, and that ROS scavengers suppress the cocaine-induced increase of DA in the NAc apparently without the involvement of dopamine transporter (DAT). Together, it is suggested that cocaine stimulates the ROS production in the NAc neurons that leads partly to the increase of DA and the subsequent expression of cocaine-self administration.

It has been demonstrated that Sig-1R antagonists alone do not affect the cocaine self-administration. Typical DAT inhibitors are known to shift the cocaine dose-effect curve to the left. However, combination of Sig-1R antagonists and DAT inhibitors decreases cocaine self-administration [127]. Underlying molecular mechanisms in this regard are largely unknown. Whether the Sig-1R-related ROS-dependent pathway may be involved in the self-administration of cocaine is also not known at present. Similar to cocaine self-administration, it has been reported that METH self-administration is attenuated by dual inhibition of DAT and sigma receptors [128].

Previous studies have provided evidence that the ROS signaling plays important roles in the effects of METH in vivo and in vitro. It was shown that METH increases the ROS production via various pathways [129, 130] including the inhibition of mitochondrial functions [131] and the stimulation of the NADPH oxidase (NOX) activity [132]. METH-induced ROS production is implicated in METH effects on neuronal degeneration [133, 134], toxicity in various cell types [135, 136], behavioral hyperactivity [137, 138], and hyperthermia [139, 140]. Notably, ROS-reducing agents including ROS scavengers and NOX inhibitors attenuate those effects of METH.

Specific involvement of the Sig-1R in the action of METH has been demonstrated in the METH-induced locomotor activity as well as in behavioral sensitization. Selective Sig-1R antagonists or Sig-1R antisense decrease the behavioral response caused by METH [55, 141]. On the other hand, METH-induced ROS generation, apoptosis (at μM concentration), necrotic cell deaths (at mM concentration), or DA release is inhibited by subtype non-selective sigma antagonists in differentiated NG108–15 cells [142, 143]. Interestingly, 1,3-di(2-tolyl)-guanidine (DTG), a sigma agonist, shifts the METH dose-response curve to the left in the METH-induced cell death. In mice, sigma antagonists block the METH-induced hyperthermia and damage in dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons as seen in the depletion of dopamine and serotonin, and the reduction of the transporters in the striatum in addition to blocking the locomotor activity and memory impairment caused by METH [144–147]. It should be mentioned that METH-induced hyperthermia apparently exacerbates the neuronal toxicity of METH [143, 148]. The Sig-1R’s specific role in the molecular mechanism underlying the METH-induced effects is unknown at present. However, it is conceivable that the Sig-1R may play a role in the neuronal and behavioral effects of METH by regulating the ROS signaling.

Regulation of Autophagy

Autophagy is a lysosomal degradation pathway responsible for the turnover of cellular organelles and larger protein aggregates whose sizes are beyond that the proteasome can handle. The autophagy process includes the sequestration of cytoplasmic components within a double-membrane compartment (autophagosome) and the subsequent fusion of autophagosome with lysosomes, followed by degradation. Autophagy can be pro-survival and pro-death depending on the cellular types and conditions.

Recently a couple of studies have demonstrated the involvement of the Sig-1R in the process of autophagy. Knockdown of the Sig-1R impairs the fusion between autophagosome and lysosomes, thus leading to the accumulation of autophagosome. The accumulation of autophagosome is implicated in ALS, one of Sig-1R-related neurodegenerative disease [86]. Cao et al. recently demonstrated the cocaine-induced autophagy and suggested that the Sig-1R plays a role in the cocaine-induced autophagy in a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and Beculin-1-dependent manner in astrocytes which are the most abundant cell type in the brain that supports neuronal survival. The report showed that the knockdown of Sig-1R or a Sig-1R antagonist attenuates the cocaine-induced autophagy [149]. Cocaine-induced autophagy causes the apoptosis-independent cell death and may thus be implicated in the neuronal toxicity of cocaine.

It has been reported that cocaine is capable of stimulating inflammatory responses in the CNS by activating microglia. In response to prolonged exposure to cocaine, activated microglia produces cytokine, chemokine and neurotoxic factors that can cause neuronal damage and dysfunction. A recent study showed that autophagy is involved in the cocaine-induced activation of microglia. Cocaine mediates the ROS production and ER stress whereby inducing autophagy that stimulates the production and secretion of proinflammatory factors in microglial cells. Indeed, induction of autophagy by cocaine is indicated by increased levels of autophagy markers, BECN1, ATG5 and MAP1LC3B-II, in the brain of mice repeatedly treated with cocaine [150]. Thus, the cocaine-induced ROS generation leads to autophagy that activates microglia. Whether the cocaine-induced microglial activation may involve the Sig-1R is unknown at present.

METH-induced autophagy is often tested in dopaminergic neurons because the disruption of dopaminergic system is a key effect of METH. Micromolar concentrations of METH, which do not kill cells, induce autophagy to protect cells from apoptosis [151, 152]. This autophagy as such is speculated as an early cellular response to METH intoxication. High concentrations (mM) of METH, however, induce autophagy in a ROS dependent manner, leading to the activation of apoptosis and cell death [153–155]. Thus, the moderate induction of autophagy by non-toxic concentration of METH is pro-survival whereas excess METH activates the autophagy that kills cells. Sigma antagonists have been shown to be protective against the METH-induced neuronal damage in vivo and in vitro [144–147]. Thus, the Sig-1R may participate in the METH-induced neuronal damages by the Sig-1R’s ability to regulate autophagy via mechanisms as mentioned above.

Conclusions

The exact molecular mechanisms of actions of psychostimulants remain largely unknown even though behavioral and pharmacological studies have rapidly advanced in this field. As such, there is no effective medication against psychostimulant-related disorders at present. It is apparent that targeting monoamine systems alone may not be enough to develop effective treatments. The Sig-1R has been implicated in the actions of psychostimulants including cocaine and METH and is expected to be a potential target for treatment development.

The Sig-1R has a wide variety of functions in the cell. Those functions regulated by the Sig-1R include the protein stability, intracellular Ca2+ signaling, gene transcription, ER and oxidative stress signaling, protein degradation by the ER-associated protein degradation and autophagy. In turn, those cellular functions could be affected by cocaine and METH via the involvement of the Sig-1R, eventually leading to functional alterations or damage in the cell.

It has been suggested that the Sig-1R may relate to the abuse of ethanol and nicotine. Although the Sig-1R itself does not bind ethanol or nicotine, the Sig-1R ligands modulate behavioral responses to ethanol and nicotine. Perhaps the Sig-1R may indirectly participate in the addictive processes of ethanol or nicotine in a manner which has yet to be unveiled.

In summary, the exact roles of the Sig-1R in the actions of psychostimulants or other abused substances await to be fully understood. Understanding the mechanism of actions for the Sig-1R in its full spectrum will certainly advance our understanding of this unique receptor and its exact roles in the actions of cocaine and METH in particular, but perhaps also other substances of abuse as well.

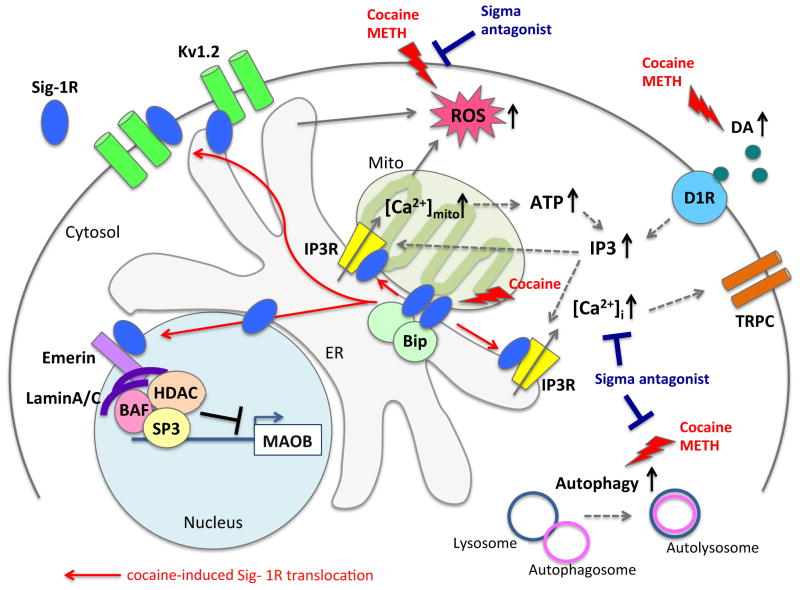

Figure 3. Potential Sig-1R-involved molecular mechanisms in the actions of cocaine and methamphetamine (METH).

Cocaine dissociates Sig-1R from Bip/GRP78 and activates the chaperone activity of Sig-1R. Sig-1R stabilizes IP3R leading to the increase of intracellular calcium concentration. Cocaine induces the translocation of Sig-1R from ER to the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope, thus intensifying Sig-1R interaction with target proteins. At the plasma membrane, Sig-1R modulates the function of potassium channels by interacting with Kv1.2 subunit. At the nuclear envelope, cocaine through Sig-1R can promote the formation of the chromatin remodeling complex composed of emerin/HDAC/BAF that binds to suppress the gene transcription of MAOB. Cocaine or METH induces the ROS production and autophagy which can be inhibited by sigma receptor antagonists. Abbreviations: ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Mito, mitochondria; DA, dopamine; D1R, dopamine D1 receptor; TRPC, transient receptor potential canonical; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate;IP3R, IP3 receptor; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; BAF, barrier-to-auto autointegration factor; HDAC, histone deacetylase; MAOB, monoamine oxidase B; [Ca2+]i, intracellular Ca2+ concentration; [Ca2+]mito, mitochondrion Ca2+ concentration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, DHHS, U.S.A. Yuko Yasui was supported in part by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Sciences.

References

- 1.Martin WR, et al. The effects of morphine- and nalorphine- like drugs in the nondependent and morphine-dependent chronic spinal dog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976;197(3):517–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su TP. Evidence for sigma opioid receptor: binding of [3H]SKF-10047 to etorphine-inaccessible sites in guinea-pig brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982;223(2):284–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mickelson MM, Lahti RA. Demonstration of non-opioid sigma binding with (d)3H-SKF 10047 in guinea pig brain. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1985;47(2):255–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaupel DB. Naltrexone fails to antagonize the sigma effects of PCP and SKF 10,047 in the dog. Eur J Pharmacol. 1983;92(3–4):269–74. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen WD, Hellewell SB, McGarry KA. Evidence for a multi-site model of the rat brain sigma receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;163(2–3):309–18. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coccini T, et al. Two subtypes of enteric non-opioid sigma receptors in guinea-pig cholinergic motor neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 1991;198(1):105–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(91)90570-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Georg A, Friedl A. Identification and characterization of two sigma-like binding sites in the mouse neuroblastoma x rat glioma hybrid cell line NG108-15. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259(2):479–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hellewell SB, Bowen WD. A sigma-like binding site in rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells: decreased affinity for (+)-benzomorphans and lower molecular weight suggest a different sigma receptor form from that of guinea pig brain. Brain Res. 1990;527(2):244–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hellewell SB, et al. Rat liver and kidney contain high densities of sigma 1 and sigma 2 receptors: characterization by ligand binding and photoaffinity labeling. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;268(1):9–18. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kavanaugh MP, et al. Identification of the binding subunit of the sigma-type opiate receptor by photoaffinity labeling with 1-(4-azido-2-methyl[6-3H]phenyl)-3-(2-methyl[4,6-3H]phenyl)guanidine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(8):2844–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanner M, et al. Purification, molecular cloning, and expression of the mammalian sigma1-binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(15):8072–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong W, Werling LL. Evidence that the sigma(1) receptor is not directly coupled to G proteins. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;408(2):117–25. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00774-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell. 2007;131(3):596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jbilo O, et al. Purification and characterization of the human SR 31747A-binding protein. A nuclear membrane protein related to yeast sterol isomerase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(43):27107–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, et al. Identification of the PGRMC1 protein complex as the putative sigma-2 receptor binding site. Nat Commun. 2011;2:380. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Waarde A, et al. Potential applications for sigma receptor ligands in cancer diagnosis and therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1848(10 Pt B):2703–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abate C, et al. Elements in support of the ‘non-identity’ of the PGRMC1 protein with the sigma2 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;758:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu Uyen B, TAM, Chu Ming-Liang, Yang Huan, Schulman Amanda, Mesangeau Christophe, McCurdy Christopher R, Guo Lian-Wang, Ruoho Arnold E. The Sigma-2 Receptor and Progesterone Receptor Membrane Component 1 are Different Binding Sites Derived From Independent Genes. EBioMedicine. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seth P, et al. Cloning and functional characterization of a sigma receptor from rat brain. J Neurochem. 1998;70(3):922–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70030922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan YX, et al. Cloning and characterization of a mouse sigma1 receptor. J Neurochem. 1998;70(6):2279–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70062279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kekuda R, et al. Cloning and functional expression of the human type 1 sigma receptor (hSigmaR1) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229(2):553–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamura K, et al. In vivo evaluation of [(11)C]SA4503 as a PET ligand for mapping CNS sigma(1) receptors. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27(3):255–61. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen VH, et al. Comparison of binding parameters of sigma 1 and sigma 2 binding sites in rat and guinea pig brain membranes: novel subtype-selective trishomocubanes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;311(2–3):233–40. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seth P, et al. Expression pattern of the type 1 sigma receptor in the brain and identity of critical anionic amino acid residues in the ligand-binding domain of the receptor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1540(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi T, et al. Targeting ligand-operated chaperone sigma-1 receptors in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15(5):557–77. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.560837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi T. Conversion of psychological stress into cellular stress response: roles of the sigma-1 receptor in the process. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;69(4):179–91. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skuza G, Rogoz Z. Antidepressant-like effect of PRE-084, a selective sigma1 receptor agonist, in Albino Swiss and C57BL/6J mice. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61(6):1179–83. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(09)70181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohi K, et al. The SIGMAR1 gene is associated with a risk of schizophrenia and activation of the prefrontal cortex. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(5):1309–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuno K, et al. Reduction of 4-cyclohexyl-1-[(1R)-1,2-diphenylethyl]-piperazine-induced memory impairment of passive avoidance performance by sigma 1 receptor agonists in mice. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 1998;20(7):575–80. doi: 10.1358/mf.1998.20.7.485721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maurice T, et al. The attenuation of learning impairments induced after exposure to CO or trimethyltin in mice by sigma (sigma) receptor ligands involves both sigma1 and sigma2 sites. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127(2):335–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elbrond-Bek H, et al. 2-(Cyclohexylamino)-1-(4-cyclopentylpiperazin-1-yl)-2-methylpropan-1-one, a novel compound with neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects in vitro. Neurochem Int. 2011;59(6):821–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin JL, et al. Roles of sigma-1 receptors in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(4):4808–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsai SY, et al. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18(12):1461–76. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.972939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen L, et al. Role of sigma-1 receptors in neurodegenerative diseases. J Pharmacol Sci. 2015;127(1):17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kotagale NR, et al. Agmatine attenuates neuropathic pain in sciatic nerve ligated rats: modulation by hippocampal sigma receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;714(1–3):424–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhuiyan MS, Tagashira H, Fukunaga K. Crucial interactions between selective serotonin uptake inhibitors and sigma-1 receptor in heart failure. J Pharmacol Sci. 2013;121(3):177–84. doi: 10.1254/jphs.12r13cp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spitzer D, et al. Use of multifunctional sigma-2 receptor ligand conjugates to trigger cancer-selective cell death signaling. Cancer Res. 2012;72(1):201–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeng C, et al. Sigma-2 ligands induce tumour cell death by multiple signalling pathways. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(4):693–701. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crawford KW, Bowen WD. Sigma-2 receptor agonists activate a novel apoptotic pathway and potentiate antineoplastic drugs in breast tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 2002;62(1):313–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wheeler KT, et al. Sigma-2 receptors as a biomarker of proliferation in solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(6):1223–32. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hou C, et al. Characterization of a novel iodinated sigma-2 receptor ligand as a cell proliferation marker. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33(2):203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchez C, Papp M. The selective sigma2 ligand Lu 28–179 has an antidepressant-like profile in the rat chronic mild stress model of depression. Behav Pharmacol. 2000;11(2):117–24. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettit HO, et al. Extracellular concentrations of cocaine and dopamine are enhanced during chronic cocaine administration. J Neurochem. 1990;55(3):798–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nayak PK, Misra AL, Mule SJ. Physiological disposition and biotransformation of (3H) cocaine in acutely and chronically treated rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1976;196(3):556–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Misra AL, et al. Identification of norcocaine as a metabolite of (3H)-cocaine in rat brain. Experientia. 1974;30(11):1312–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01945203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benuck M, Lajtha A, Reith ME. Pharmacokinetics of systemically administered cocaine and locomotor stimulation in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;243(1):144–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamanaka Y, Yamamoto T, Egashira T. Methamphetamine-induced behavioral effects and releases of brain catecholamines and brain concentrations of methamphetamine in mice. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1983;33(1):33–40. doi: 10.1254/jjp.33.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeffcoat AR, et al. Cocaine disposition in humans after intravenous injection, nasal insufflation (snorting), or smoking. Drug Metab Dispos. 1989;17(2):153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cook CE, et al. Pharmacokinetics of methamphetamine self-administered to human subjects by smoking S-(+)-methamphetamine hydrochloride. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21(4):717–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mendelson J, et al. Methamphetamine and ethanol interactions in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;57(5):559–68. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rambousek L, et al. Sex differences in methamphetamine pharmacokinetics in adult rats and its transfer to pups through the placental membrane and breast milk. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:138–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Human methamphetamine pharmacokinetics simulated in the rat: single daily intravenous administration reveals elements of sensitization and tolerance. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(5):941–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Banks ML, et al. Relationship between discriminative stimulus effects and plasma methamphetamine and amphetamine levels of intramuscular methamphetamine in male rhesus monkeys. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakai T, et al. Distribution and excretion of methamphetamine and its metabolites in rats. III. Time-course of concentrations in blood and bile, and distribution after intravenous administration. Xenobiotica. 1985;15(1):31–40. doi: 10.3109/00498258509045332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen EC, et al. Involvement of sigma (sigma) receptors in the acute actions of methamphetamine: receptor binding and behavioral studies. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49(5):638–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matsumoto RR, et al. Involvement of sigma receptors in the behavioral effects of cocaine: evidence from novel ligands and antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42(8):1043–55. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garces-Ramirez L, et al. Sigma receptor agonists: receptor binding and effects on mesolimbic dopamine neurotransmission assessed by microdialysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(3):208–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hiranita T, et al. Stimulants as specific inducers of dopamine-independent sigma agonist self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;347(1):20–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.207522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharkey J, et al. Cocaine binding at sigma receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;149(1–2):171–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matsumoto RR, et al. Sigma (sigma) receptors as potential therapeutic targets to mitigate psychostimulant effects. Adv Pharmacol. 2014;69:323–86. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robson MJ, et al. Sigma-1 receptors: potential targets for the treatment of substance abuse. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(7):902–19. doi: 10.2174/138161212799436601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsumoto RR, et al. Novel analogs of the sigma receptor ligand BD1008 attenuate cocaine-induced toxicity in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;492(1):21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lever JR, et al. A selective sigma-2 receptor ligand antagonizes cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion in mice. Synapse. 2014;68(2):73–84. doi: 10.1002/syn.21717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pal A, et al. Identification of regions of the sigma-1 receptor ligand binding site using a novel photoprobe. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72(4):921–33. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ortega-Roldan JL, Ossa F, Schnell JR. Characterization of the human sigma-1 receptor chaperone domain structure and binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP) interactions. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(29):21448–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.450379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ortega-Roldan JL, et al. Solution NMR studies reveal the location of the second transmembrane domain of the human sigma-1 receptor. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(5):659–65. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aydar E, et al. The sigma receptor as a ligand-regulated auxiliary potassium channel subunit. Neuron. 2002;34(3):399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Su TP, London ED, Jaffe JH. Steroid binding at sigma receptors suggests a link between endocrine, nervous, and immune systems. Science. 1988;240(4849):219–21. doi: 10.1126/science.2832949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Palmer CP, et al. Sigma-1 receptors bind cholesterol and remodel lipid rafts in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 2007;67(23):11166–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Monnet FP, Maurice T. The sigma1 protein as a target for the non-genomic effects of neuro(active)steroids: molecular, physiological, and behavioral aspects. J Pharmacol Sci. 2006;100(2):93–118. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cr0050032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bergeron R, de Montigny C, Debonnel G. Potentiation of neuronal NMDA response induced by dehydroepiandrosterone and its suppression by progesterone: effects mediated via sigma receptors. J Neurosci. 1996;16(3):1193–202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01193.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ramachandran S, et al. The sigma1 receptor interacts with N-alkyl amines and endogenous sphingolipids. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;609(1–3):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hayashi T, Fujimoto M. Detergent-resistant microdomains determine the localization of sigma-1 receptors to the endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria junction. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77(4):517–28. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hayashi T, et al. The lifetime of UDP-galactose:ceramide galactosyltransferase is controlled by a distinct endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) regulated by sigma-1 receptor chaperones. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(51):43156–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.380444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsai SY, et al. Sigma-1 receptor regulates Tau phosphorylation and axon extension by shaping p35 turnover via myristic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(21):6742–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1422001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamamoto H, et al. Amino acid residues in the transmembrane domain of the type 1 sigma receptor critical for ligand binding. FEBS Lett. 1999;445(1):19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pal A, et al. Juxtaposition of the steroid binding domain-like I and II regions constitutes a ligand binding site in the sigma-1 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(28):19646–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802192200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ganapathy ME, et al. Molecular and ligand-binding characterization of the sigma-receptor in the Jurkat human T lymphocyte cell line. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289(1):251–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fontanilla D, et al. The hallucinogen N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) is an endogenous sigma-1 receptor regulator. Science. 2009;323(5916):934–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1166127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mori T, et al. Sigma-1 receptor chaperone at the ER-mitochondrion interface mediates the mitochondrion-ER-nucleus signaling for cellular survival. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Area-Gomez E, et al. Upregulated function of mitochondria-associated ER membranes in Alzheimer disease. Embo j. 2012;31(21):4106–23. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schrader M, et al. The different facets of organelle interplay-an overview of organelle interactions. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2015;3:56. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2015.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hayashi T, et al. MAM: more than just a housekeeper. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(2):81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van Vliet AR, Verfaillie T, Agostinis P. New functions of mitochondria associated membranes in cellular signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843(10):2253–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shioda N, et al. Expression of a truncated form of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein, sigma1 receptor, promotes mitochondrial energy depletion and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(28):23318–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.349142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vollrath JT, et al. Loss of function of the ALS protein SigR1 leads to ER pathology associated with defective autophagy and lipid raft disturbances. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1290. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Balasuriya D, et al. A direct interaction between the sigma-1 receptor and the hERG voltage-gated K+ channel revealed by atomic force microscopy and homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF(R)) J Biol Chem. 2014;289(46):32353–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.603506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kourrich S, et al. Dynamic interaction between sigma-1 receptor and Kv1.2 shapes neuronal and behavioral responses to cocaine. Cell. 2013;152(1–2):236–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mavlyutov TA, et al. The sigma-1 receptor is enriched in postsynaptic sites of C-terminals in mouse motoneurons. An anatomical and behavioral study. Neuroscience. 2010;167(2):247–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mavlyutov TA, Epstein M, Guo LW. Subcellular localization of the sigma-1 receptor in retinal neurons - an electron microscopy study. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10689. doi: 10.1038/srep10689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koulen P, et al. Polycystin-2 is an intracellular calcium release channel. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(3):191–7. doi: 10.1038/ncb754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ivanova H, et al. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-isoform diversity in cell death and survival. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843(10):2164–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hayashi T, Maurice T, Su TP. Ca(2+) signaling via sigma(1)-receptors: novel regulatory mechanism affecting intracellular Ca(2+) concentration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293(3):788–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hayashi T, Su TP. Regulating ankyrin dynamics: Roles of sigma-1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(2):491–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Szabadkai G, et al. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J Cell Biol. 2006;175(6):901–11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Abou-Lovergne A, et al. Investigation of the role of sigma1-receptors in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate dependent calcium signaling in hepatocytes. Cell Calcium. 2011;50(1):62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tagashira H, et al. Stimulation of sigma1-receptor restores abnormal mitochondrial Ca(2)(+) mobilization and ATP production following cardiac hypertrophy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(4):3082–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tagashira H, Bhuiyan MS, Fukunaga K. Diverse regulation of IP3 and ryanodine receptors by pentazocine through sigma1-receptor in cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305(8):H1201–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00300.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tagashira H, et al. Fluvoxamine rescues mitochondrial Ca2+ transport and ATP production through sigma(1)-receptor in hypertrophic cardiomyocytes. Life Sci. 2014;95(2):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Barr JL, et al. Mechanisms of activation of nucleus accumbens neurons by cocaine via sigma-1 receptor-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-transient receptor potential canonical channel pathways. Cell Calcium. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Medvedev IO, et al. D1 dopamine receptor coupling to PLCbeta regulates forward locomotion in mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33(46):18125–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2382-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kurokawa K, et al. Regulation of type 1 inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor by dopamine receptors in cocaine-induced place conditioning. Synapse. 2012;66(2):180–6. doi: 10.1002/syn.20997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kurokawa K, Mizuno K, Ohkuma S. Possible involvement of type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors up-regulated by dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in mouse nucleus accumbens neurons in the development of methamphetamine-induced place preference. Neuroscience. 2012;227:22–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mizuno K, Kurokawa K, Ohkuma S. Dopamine D1 receptors regulate type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor expression via both AP-1- and NFATc4-mediated transcriptional processes. J Neurochem. 2012;122(4):702–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mizuno K, Kurokawa K, Ohkuma S. Regulation of type 1 IP(3) receptor expression by dopamine D2-like receptors via AP-1 and NFATc4 activation. Neuropharmacology. 2013;71:264–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Romieu P, et al. Involvement of the sigma(1) receptor in cocaine-induced conditioned place preference: possible dependence on dopamine uptake blockade. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26(4):444–55. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Romieu P, et al. The sigma1 (sigma1) receptor activation is a key step for the reactivation of cocaine conditioned place preference by drug priming. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;175(2):154–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1814-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Romieu P, Martin-Fardon R, Maurice T. Involvement of the sigma1 receptor in the cocaine-induced conditioned place preference. Neuroreport. 2000;11(13):2885–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009110-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hiroi N, White NM. The amphetamine conditioned place preference: differential involvement of dopamine receptor subtypes and two dopaminergic terminal areas. Brain Res. 1991;552(1):141–52. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90672-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cervo L, Samanin R. Effects of dopaminergic and glutamatergic receptor antagonists on the acquisition and expression of cocaine conditioning place preference. Brain Res. 1995;673(2):242–50. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01420-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Martina M, et al. The sigma-1 receptor modulates NMDA receptor synaptic transmission and plasticity via SK channels in rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2007;578(Pt 1):143–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Van de Vosse DW, et al. Role of the nuclear envelope in genome organization and gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2011;3(2):147–66. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tsai SA, et al. Sigma-1 receptor mediates cocaine-induced transcriptional regulation by recruiting chromatin-remodeling factors at the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518894112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Tsai SY, Rothman RK, Su TP. Insights into the Sigma-1 receptor chaperone’s cellular functions: a microarray report. Synapse. 2012;66(1):42–51. doi: 10.1002/syn.20984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ho MC, et al. Chronic treatment with monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors decreases cocaine reward in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;205(1):141–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tsai SY, et al. Sigma-1 receptors regulate hippocampal dendritic spine formation via a free radical-sensitive mechanism involving Rac1xGTP pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(52):22468–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909089106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang J, et al. Sigma 1 receptor regulates the oxidative stress response in primary retinal Muller glial cells via NRF2 signaling and system xc(-), the Na(+)-independent glutamate-cystine exchanger. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;86:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Meunier J, Hayashi T. Sigma-1 receptors regulate Bcl-2 expression by reactive oxygen species-dependent transcriptional regulation of nuclear factor kappaB. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332(2):388–97. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.160960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Levine B, Sinha S, Kroemer G. Bcl-2 family members: dual regulators of apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4(5):600–6. doi: 10.4161/auto.6260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Pizzinat N, et al. Reactive oxygen species production by monoamine oxidases in intact cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1999;359(5):428–31. doi: 10.1007/pl00005371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Choi SR, et al. Spinal sigma-1 receptors activate NADPH oxidase 2 leading to the induction of pain hypersensitivity in mice and mechanical allodynia in neuropathic rats. Pharmacol Res. 2013;74:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Natsvlishvili N, et al. Sigma-1 receptor directly interacts with Rac1-GTPase in the brain mitochondria. BMC Biochem. 2015;16:11. doi: 10.1186/s12858-015-0040-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zhao J, et al. Sigma receptor ligand, (+)-pentazocine, suppresses inflammatory responses of retinal microglia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(6):3375–84. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Yao H, et al. Molecular mechanisms involving sigma receptor-mediated induction of MCP-1: implication for increased monocyte transmigration. Blood. 2010;115(23):4951–62. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Dietrich JB, et al. Acute or repeated cocaine administration generates reactive oxygen species and induces antioxidant enzyme activity in dopaminergic rat brain structures. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48(7):965–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jang EY, et al. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in cocaine-taking behaviors in rats. Addict Biol. 2015;20(4):663–75. doi: 10.1111/adb.12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hiranita T, et al. Decreases in cocaine self-administration with dual inhibition of the dopamine transporter and sigma receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;339(2):662–77. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.185025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hiranita T, et al. Preclinical efficacy of N-substituted benztropine analogs as antagonists of methamphetamine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;348(1):174–91. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.208264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Brown JM, Yamamoto BK. Effects of amphetamines on mitochondrial function: role of free radicals and oxidative stress. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;99(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Riddle EL, Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR. Mechanisms of methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Aaps j. 2006;8(2):E413–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02854914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Mashayekhi V, et al. Induction of mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) pore opening and ROS formation as a mechanism for methamphetamine-induced mitochondrial toxicity. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2014;387(1):47–58. doi: 10.1007/s00210-013-0919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Park M, Hennig B, Toborek M. Methamphetamine alters occludin expression via NADPH oxidase-induced oxidative insult and intact caveolae. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(2):362–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]