Abstract

Aims:

People with serious mental illness are increasingly turning to popular social media, including Facebook, Twitter or YouTube, to share their illness experiences or seek advice from others with similar health conditions. This emerging form of unsolicited communication among self-forming online communities of patients and individuals with diverse health concerns is referred to as peer-to-peer support. We offer a perspective on how online peer-to-peer connections among people with serious mental illness could advance efforts to promote mental and physical wellbeing in this group.

Methods:

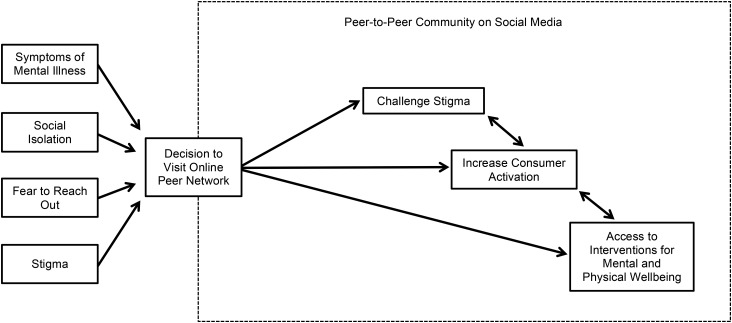

In this commentary, we take the perspective that when an individual with serious mental illness decides to connect with similar others online it represents a critical point in their illness experience. We propose a conceptual model to illustrate how online peer-to-peer connections may afford opportunities for individuals with serious mental illness to challenge stigma, increase consumer activation and access online interventions for mental and physical wellbeing.

Results:

People with serious mental illness report benefits from interacting with peers online from greater social connectedness, feelings of group belonging and by sharing personal stories and strategies for coping with day-to-day challenges of living with a mental illness. Within online communities, individuals with serious mental illness could challenge stigma through personal empowerment and providing hope. By learning from peers online, these individuals may gain insight about important health care decisions, which could promote mental health care seeking behaviours. These individuals could also access interventions for mental and physical wellbeing delivered through social media that could incorporate mutual support between peers, help promote treatment engagement and reach a wider demographic. Unforeseen risks may include exposure to misleading information, facing hostile or derogatory comments from others, or feeling more uncertain about one's health condition. However, given the evidence to date, the benefits of online peer-to-peer support appear to outweigh the potential risks.

Conclusion:

Future research must explore these opportunities to support and empower people with serious mental illness through online peer networks while carefully considering potential risks that may arise from online peer-to-peer interactions. Efforts will also need to address methodological challenges in the form of evaluating interventions delivered through social media and collecting objective mental and physical health outcome measures online. A key challenge will be to determine whether skills learned from peers in online networks translate into tangible and meaningful improvements in recovery, employment, or mental and physical wellbeing in the offline world.

Key words: Internet, mental health, mental illness stigma, peer support, social network

‘I don't know what led me to find your videos, but by some sort of luck I found your videos a month before I was diagnosed with schizophrenia. It's been a very hard and trying few months but you have given me a lot of hope. So thank you, keep up the good work.’

(Individual with schizophrenia commenting on YouTube)

‘I comment on many of these posts because if I give one person hope it is more than worth it to do so. Depression nearly cost me my life a couple of times when I was in my 20s. It was really very rough at times, I know there are many, many out there who want to give up but don't!!! THERE IS HELP OUT THERE! There are people who care!!!’

(Individual with bipolar disorder commenting on Facebook)

Posts like these on popular social media such as Facebook or YouTube convey acceptance, hope, validation and illustrate the give-and-take nature of connecting with peers online. Increasingly, individuals with serious mental illnesses like schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder are turning to social media to talk about their illness experiences, seek advice and learn from and support each other (Gowen et al. 2012; Naslund et al. 2014; Miller et al. 2015). This unsolicited communication occurs naturally and involves self-forming online communities of individuals who share an understanding of living with mental illness. Referred to as online peer-to-peer support, this emerging form of social interaction has been described as one of the most transformational features of the Internet (Ziebland & Wyke, 2012) and may present new opportunities to promote recovery, self-esteem and mental and physical wellbeing among individuals with serious mental illness.

Worldwide, serious mental illness is a leading cause of disability (Murray & Lopez, 1997) and is associated with debilitating symptoms of anxiety, depression and low motivation (Kessler et al. 2003). Being labelled mentally ill, and the ensuing societal stigma and prejudice, can have devastating effects on quality of life, self-efficacy and ability to pursue meaningful life goals (Corrigan, 1998). For people with serious mental illness the effects of stigma, feelings of hopelessness and helplessness, and resulting social marginalisation and withdrawal lead to increased risk of substance use, poverty, homelessness, unemployment, hospitalisation and suicide (Dixon, 1995; Corrigan, 2004; Folsom et al. 2005; Pompili et al. 2008). There are also numerous challenges to addressing these concerns from a clinical perspective. For example, to reach individuals with serious mental illness, it is necessary to overcome barriers such as social isolation, reluctance to use formal health care services and challenging social circumstances such as traumatic life events or disruptive home environments (RachBeisel et al. 1999; Hert et al. 2011). Online peer networks may offer novel approaches for supporting and engaging this high-risk group in treatment efforts.

By early 2015, over 2 billion people globally had active social media accounts (Kemp, 2015). Social media refers to interactive web and mobile platforms through which individuals and communities share, co-create, or exchange information, ideas, photos, or videos within a virtual network. Online social networking represents a prominent form of communication in many people's lives. For individuals with stigmatised illnesses, such as serious mental illness, social media may make it possible to connect with others who share similar health conditions and to seek or disclose health information without having to reveal one's personal identity (Berger et al. 2005). Additionally, many people with serious mental illness experience symptoms that interfere with socialising in face-to-face encounters (Dickerson et al. 2001). Therefore social media may help to facilitate social connections among this group by overcoming obstacles such as stigma and mental health symptoms (Highton-Williamson et al. 2015).

Research suggests that people with serious mental illness are interested and willing to form connections with others through social media. A survey of young adults found that those with mental illness were more likely to express personal views through blogging, build friendships on social media and connect with people online who have shared interests compared with those without mental illness (Gowen et al. 2012). Similarly, another survey found that adults with schizophrenia were as likely as adults without mental illness to form social connections online despite having fewer offline relationships, lower income and less Internet access (Spinzy et al. 2012). In a qualitative study, popular social media appeared useful for allowing people with serious mental illness to feel less alone and to find hope and to support each other, and to share personal stories and strategies for coping with day-to-day challenges of living with a mental illness (Naslund et al. 2014). Other studies have found that online support groups, forums and chat rooms serve as important venues for discussing sensitive mental health conditions (Kummervold et al. 2002), and for disclosing personal experiences of living with schizophrenia or seeking and sharing information related to symptoms and medications (Haker et al. 2005).

Despite this mounting evidence, limited attention has been directed at utilising these online networks to disseminate materials for mental health education or support, or to widen access to evidence-based services among these high-risk individuals. In this paper we present our perspective on how interactions among people with serious mental illness over social media, referred to as online peer-to-peer support, may afford important opportunities to advance treatment efforts aimed at promoting mental and physical wellbeing in this group. First, we consider the importance of forming social connections and the role of social media among people with serious mental illness. Then, we propose three areas where online peer-to-peer connections may have a profound impact for these individuals. These include challenging stigma, increasing consumer activation, and accessing interventions for mental and physical wellbeing. We carefully consider the potential risks associated with interacting with peers online. To conclude, we discuss important challenges ahead and recommend future research directions.

Online peer-to-peer support and mental illness

Prior studies have emphasised the importance of individuals feeling connected to others and sharing a sense of belonging to a group (Brewer, 1991). Identifying with a social group is believed to increase self-esteem and self-efficacy, and reduce uncertainty about oneself (McKenna & Bargh, 1998). Among people with serious mental illness, connecting with similar others may contribute to better recovery, personal wellbeing and social integration (Davidson et al. 1999). Yet, for these individuals, identifying and reaching out to others poses numerous risks in the form of disclosure and potential disapproval, rejection, or negative attitudes (Link et al. 1997). Many people with serious mental illness also experience challenges with face-to-face communication due to impairments in cognitive and social functioning (Dickerson et al. 2001). For someone with serious mental illness, the decision to reach out and connect with others to discuss personal health issues typically occurs at a time of increased instability and when facing significant life challenges (Perry & Pescosolido, 2015). Seeking support and social connection is therefore a critical point in the lives of people with serious mental illness, and the decision of who to reach out to may be detrimental in determining their path to successful recovery and wellbeing.

Through social media, people with serious mental illness can potentially identify similar others and experience benefits of group participation at their own convenience, while remaining anonymous and avoiding challenges associated with interpersonal deficits such as interpreting social cues or non-verbal communication (Mittal et al. 2007; Highton-Williamson et al. 2015). Social media overcomes geographic boundaries and time constraints, and allows users to choose whether or not to actively create content, disclose personal health information, post comments, or passively view content posted by others. Research suggests that within an online network, both individuals who choose to share content or connect with different users, as well as those who choose to seek health information without interacting with others can experience important benefits (van Uden-Kraan et al. 2008; Mo & Coulson, 2010; Chung, 2014). Compared with spontaneous face-to-face encounters, social media users maintain greater control meaning that they can choose their own level of engagement and the extent to which they interact with others. This may be especially important for people with serious mental illness because social media may help them overcome debilitating effects of their illness such as information processing challenges, increased social anxiety, or difficulties with social interaction (Schrank et al. 2010). On social media individuals with serious mental illness can choose whether to post content and how quickly to respond to comments, and can revisit conversations or seek greater clarity at their own pace. For someone experiencing mental health symptoms combined with fear of stigma and rejection, this added control through online communication may be empowering.

Social media also represents a user-driven environment, where individuals with Internet access through their mobile device or computer can have a voice and the opportunity to express themselves and connect to a larger online community. Online peer-to-peer networks represent a significant contrast to traditional biomedical or psychiatric approaches to mental health care. Many people with serious mental illness have had to fight against discrimination and injustice, and advocate for basic human rights and mental health care reform (Tomes, 2006). For this group, social media may serve as a platform through which many of these individuals can continue to challenge prejudiced societal views, question authoritarian medical practices and share positive attitudes and beliefs.

New opportunities through online peer-to-peer support

We take the perspective that when an individual with serious mental illness decides to connect with similar others online, it represents a critical point in their illness experience. These individuals are likely facing significant personal challenges, social isolation, or fears about how others will view them, which may prompt them to seek information or support online. In Fig. 1, we propose a conceptual model to illustrate how online peer-to-peer connections may afford individuals with serious mental illness opportunities to challenge stigma, increase consumer activation and access online interventions. Our conceptual model is informed by existing literature including studies of online communities and online support groups for mental illness as well as other patient groups with diverse health conditions, and suggests how individuals with serious mental illness may benefit from peer-to-peer interactions following the initial decision to visit an online community. As depicted in Fig. 1, the proposed opportunities do not necessarily occur in a sequential order.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model illustrating potential opportunities that may be available to individuals with serious mental illness after visiting an online community of peers.

Challenge stigma

When individuals with serious mental illness visit an online community they may be experiencing shame, uncertainty and feeling alone with their symptoms or illness diagnosis. These individuals may have fears about reaching out to others, driven by concerns about what other people will say or think and the possibility of rejection because of their illness (Link et al. 1997). When individuals with mental illness internalise discriminatory societal views and stereotypes, it often leads to negative consequences including diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy, and greater depressive symptoms (Corrigan, 1998). Stigma impacts an individual's ability to carry out daily activities such as work or school, to pursue life goals and to seek necessary mental health care (Link et al. 1997; Corrigan, 1998).

Online communities may serve as powerful venues where individuals with serious mental illness can challenge stigma through personal empowerment and providing hope (Lawlor & Kirakowski, 2014). Studies have shown that knowing that there are others facing similar concerns, frustrations and illness symptoms can be highly reassuring and can create a sense of belonging to a group (Harvey et al. 2007). Young adults with mental illness report that one of the primary reasons for connecting with others online is to feel less alone (Burns et al. 2009), and popular social media allows people with serious mental illness to feel connected while gaining a sense of relief from knowing that others share similar experiences and challenges (Naslund et al. 2014). Research also suggests that true self can be expressed more easily within online networks because the anonymity of the Internet can shield from disapproval or fear of making mistakes (Bargh et al. 2002). This is also important because self-expression may help protect against harmful effects of stigma (Bargh & McKenna, 2004; Whitley & Campbell, 2014). Therefore, individuals with serious mental illness may benefit from interacting with others through social media because they can be themselves without letting the challenges of their illness get in the way.

Coming out and disclosing one's illness to others is also an important approach for addressing stigma (Corrigan et al. 2010; Corrigan et al. 2013). Through online peer-to-peer communities, individuals with serious mental illness can connect with others with lived experience and openly disclose their own diagnosis while choosing to share positive stories of recovery and facts to challenge stigma and directly address widespread myths and misperceptions about living with a mental illness. Research suggests that marginalised individuals may benefit from feelings of empowerment, greater personal identity and pride by connecting with similar others online (van Uden-Kraan et al. 2009). The increase in confidence and sense of belonging gained through selectively disclosing to others online may even make individuals feel more comfortable disclosing their illness in face-to-face encounters (McKenna & Bargh, 1998). As the number of online forums, blogs, or Facebook groups dedicated to empowering and supporting people living with serious mental illness continues to grow, it is clear that online communities will serve as valuable outlets for these individuals. Future research must establish whether online peer-to-peer support effectively challenges stigma and helps overcome social isolation among individuals with serious mental illness.

Increase consumer activation

Engaging with similar others online may prompt further interest in learning what to expect, how to cope and how to approach important health care decisions. As individuals with serious mental illness increasingly use popular social media to share experiences navigating the health care system, discuss the use of different medications and communicate about the importance of finding the right doctor (Naslund et al. 2014); these online networks may promote consumer activation and mental health care seeking behaviours. A recent study found that many people with mental illness were motivated to seek formal mental health care after first searching or discussing concerns with peers online (Lawlor & Kirakowski, 2014). It is possible that connecting with similar others through online networks may act as a catalyst for prompting individuals to seek formal care (Powell et al. 2003).

Learning about the experiences of others may help individuals feel at ease, know what questions to ask and know what to expect during a medical visit or hospitalisation (Lowe et al. 2009). Prior studies have shown that when someone learns about other people's personal experiences facing illness, they feel more confident and empowered in making their own health care decisions (Entwistle et al. 2011). Research also suggests that many people will seek health information online following a medical visit where they felt dissatisfied or disagreed with the advice they received from their medical provider (Raupach & Hiller, 2002).

Among people with serious mental illness who have access to medical care, research consistently shows that it is substandard (Wang et al. 2002). Peer-facilitated approaches to finding ways to better communicate with medical providers, to navigate unfamiliar health care environments and to take an active role during primary care visits may be important strategies for improving the quality of health care encounters (Bartels et al. 2013). Therefore, learning from peers through online networks may help individuals with serious mental illness realise that they can make their own health care decisions, and may help them become more empowered consumers by being better prepared for medical visits and being more proactive and assertive in their communication with health care providers. Further research is needed to determine whether seeking health information and learning tips and strategies from peers online can help individuals with serious mental illness feel more confident in their interactions with medical and mental health care providers.

Access to interventions for mental and physical wellbeing

As people with serious mental illness feel comfortable visiting online networks, there may be opportunities for these individuals to access interventions aimed at supporting mental and physical wellbeing. Interventions delivered through online communities could leverage mutual support among peers, and help promote treatment engagement and prevent study attrition (Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 2014), and reach a wider demographic including individuals who may be reluctant to seek formal services (Naslund et al. 2015b). There may be opportunities to deliver flexible interventions that allow personalisation by catering to the different needs and preferences of members of the online community (Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 2014). Interventions could be adaptive, by integrating feedback from peers within the network and making improvements to intervention design and delivery in real time. For instance, an intervention could iteratively incorporate new strategies or content suggested by community members based on the number of likes or positive feedback from others.

To date, the majority of studies of online networks among people with serious mental illness have involved survey methods, qualitative interviews, or content analyses of online discussions (Lawlor & Kirakowski, 2014). Few studies have collected objective mental or physical health outcomes over time, and only a handful of interventions have been delivered to individuals with serious mental illness using social media (Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 2014; Naslund et al. 2015c). For example, the HORYZONS social networking intervention for first episode psychosis involves the delivery of evidence-based online psychoeducation enhanced by moderated peer-to-peer support within an online forum (Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 2013, Lederman et al. 2014). Preliminary findings show that young participants were highly engaged in the HORYZONS system, and found it safe to use and empowering, and reported that it helped them feel more socially connected (Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 2013). Recent studies of online psychoeducation interventions for bipolar disorder have also included moderated discussion forums to facilitate peer-to-peer support (Simon et al. 2011; Smith et al. 2011; Todd et al. 2014; Lauder et al. 2015).

While these studies have been highly promising, there have also been mixed results. A randomised controlled trial of online peer support yielded inconclusive results regarding the benefits of online interactions among individuals with serious mental illness (Kaplan et al. 2011). However, these interventions have all been delivered through online environments developed specifically for the research studies. Using artificially created online networks may not be generalisable because these networks may lack the norms, dynamics and atmosphere of naturally occurring online communities (Lawlor & Kirakowski, 2014). Therefore, future studies should attempt to use naturally occurring peer-to-peer networks as observed on popular social media. It will be important to consider how formal interventions may alter peer dynamics within naturally occurring networks, and whether providing evidence-based services in this way might affect how individuals choose to interact with each other online.

Given the high prevalence of co-occurring mental and physical health concerns among people with serious mental illness (Sokal et al. 2004), interventions delivered through social media should be aimed at promoting both mental and physical wellbeing. Efforts could support individual empowerment, social connection, skill building, psychoeducation and mental illness recovery, while simultaneously promoting healthy lifestyle such as quitting smoking, eating healthy, establishing a regular sleep schedule and getting exercise. Efforts in the general population include interventions on Facebook for weight loss (Napolitano et al. 2013) and smoking cessation (Ramo et al. 2015) among young adults, while emerging wearable technologies could afford opportunities for peers with serious mental illness to share exercise or personal wellness goals over social media (Naslund et al. 2015a). Delivering interventions for mental and physical wellbeing through social media appears highly promising, yet the success of future interventions will depend on whether skills learned in online networks can be applied to real world contexts (Alvarez-Jimenez et al. 2014).

Risks of online peer-to-peer support

Online peer-to-peer connections are influencing the way people with serious mental illness experience their symptoms, find ways to cope and seek mental health care; yet, risks and concerns surrounding this emerging form of online communication must be carefully considered. For instance, there are risks inherent in obtaining advice from peers with unknown credentials. It is not always possible to confirm the reliability of what peers say to each other in an online network, and it is not clear how different content is perceived as trustworthy (Entwistle et al. 2011). It is also possible that learning from the experiences of others online may lead to unrealistic expectations and greater anxiety or confusion about one's own condition (Ziebland & Wyke, 2012). However, research shows that many people who visit online networks are aware of the need to evaluate the suggestions and advice provided by others with caution, and also to assess whether the information posted by others is applicable to their own health concerns (Armstrong & Powell, 2009, Schrank et al. 2010).

Social media also provides opportunities to form meaningful relationships with others, which can be beneficial, but also poses risks. Prior studies have shown that individuals can develop a dependency for online relationships (Caplan, 2003; Chung, 2013), resulting in further challenges communicating in offline environments (Crabtree et al. 2010). Online networks may also contribute to greater social withdrawal and avoidance (Lawlor & Kirakowski, 2014). However, many individuals with serious mental illness may already be highly socially isolated before seeking connections with others online, suggesting that online networks may at least provide some form of interaction or group belonging. It is also possible that online peer networks may be the only potential way to reach the most socially isolated individuals.

Online interactions with peers can generally have a positive influence, though it is possible to discover online forums that support or promote self-harm and other unhealthy or destructive behaviours (Ziebland & Wyke, 2012). Additional risks may include exposure to hostile or derogatory comments posted by others, as well as online harassment. A recent review of online social networking among people with mental illness found limited evidence of such risks (Highton-Williamson et al. 2015), though research must explore whether individuals with serious mental illness are able to retain a sense of control over negative social encounters online, or whether negative encounters further exacerbate their mental health symptoms or contribute to reduced self-esteem. These risks are not unique to online environments, and it is important to acknowledge that individuals with serious mental illness remain at elevated risk of being victims of discrimination, abuse and violent crimes in face-to-face encounters in real world settings (Goodman et al. 1997, Lam & Rosenheck, 1998; Hiday et al. 1999; Corrigan et al. 2003). Therefore, the risks of connecting with similar others through social media should always be considered in light of existing susceptibility to risks posed by offline encounters. Overall, benefits of online peer-to-peer support appear to outweigh potential concerns, though sources of risk must be explored further to inform future research efforts.

Challenges ahead and next steps

When people with serious mental illness connect with online communities of similar others to learn, share and give and receive support, it challenges dominant societal views that this alienated group lacks the technical proficiency and ability to engage in meaningful social relationships through contemporary technological platforms (Parr, 2008). Online peer networks challenge pervasive societal stigma and discrimination by giving diverse patient groups their own voice and opportunity for self-expression. As the use of popular social media continues to proliferate rapidly (Duggan, 2015), peer-to-peer interactions will increasingly become an important part of how people with serious mental illness communicate with each other.

Future research must carefully consider the mechanisms involved in online peer-to-peer connections that may be fundamental in supporting and promoting mental and physical wellbeing, as these potential behavioural mechanisms may be applicable across rapidly changing social media platforms. Future efforts must also explore whether potential benefits of online peer-to-peer support are accrued equally across income and ethnic groups. Despite promising trends of increasing social media use (Duggan, 2015) and access to mobile devices (Smith, 2015) across all demographic groups, focused efforts will be necessary to reach the most isolated and low-income individuals with serious mental illness who may have greater symptom severity, lower education and who may remain disconnected or unable to access online networks. Mobile devices have become the primary method for accessing social media (Kemp, 2015), which facilitates access among low-income individuals who rely on their mobile devices for Internet access (McGrane, 2013).

Increasing mobile connectivity and use of social media are occurring even more rapidly throughout the developing world (Pew Research Center, 2014). As popular social media becomes an integral form of communication and social connection across low-income regions, there is similar potential to leverage the bottom-up and user-driven nature of these online peer networks to support mental health recovery, empowerment and to combat stigma. This may be especially important in fragmented health care systems in low and middle income countries where access to mental health services is limited and even non-existent (Patel et al. 2007). It is possible that the greatest gains in peer-to-peer connections among people with serious mental illness will be realised across low-resource settings.

We are at the beginning of what will likely be a significant shift in the way that people with serious mental illness can challenge stigma, seek health information and access interventions aimed at providing support and promoting mental and physical wellbeing. As this research area advances, it is essential to closely involve individuals with serious mental illness who are active members of online communities to inform efforts aimed at harnessing the use of online peer networks. There are also methodological challenges to surmount, such as determining the ideal approaches for evaluating multicomponent interventions delivered through online peer networks, and identifying strategies for collecting objective mental and physical health outcome measures to determine effectiveness and impact. As Parr (2008) points out, people with serious mental illness may experience greater social connectedness, feelings of group belonging and instrumental and emotional support from online peer-to-peer support, however these individuals still live in an offline world. Therefore, the true challenge that lies ahead will be to determine whether benefits of feeling less alone, learning from similar others and gaining confidence from interacting with peers online translate into tangible and meaningful improvements in recovery, employment, or mental and physical wellbeing that will be realised in the offline world.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant number: NIMH R01 MH104555) and by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Promotion Research Center at Dartmouth (Cooperative Agreement Number U48 DP005018). The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript or decision to publish. The authors report no competing interests.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Alvarez-Jimenez M, Bendall S, Lederman R, Wadley G, Chinnery G, Vargas S, Larkin M, Killackey E, McGorry P, Gleeson J (2013). On the HORYZON: moderated online social therapy for long-term recovery in first episode psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 143, 143–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Jimenez M, Alcazar-Corcoles M, Gonzalez-Blanch C, Bendall S, McGorry P, Gleeson J (2014). Online, social media and mobile technologies for psychosis treatment: a systematic review on novel user-led interventions. Schizophrenia Research 156, 96–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong N, Powell J (2009). Patient perspectives on health advice posted on Internet discussion boards: a qualitative study. Health Expectations 12, 313–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, McKenna KY, Fitzsimons GM (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the “true self” on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues 58, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, McKenna KYA (2004). The Internet and social life. Annual Review of Psychology 55, 573–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Aschbrenner KA, Rolin SA, Hendrick DC, Naslund JA, Faber MJ (2013). Activating older adults with serious mental illness for collaborative primary care visits. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 36, 278–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, Wagner TH, Baker LC (2005). Internet use and stigmatized illness. Social Science & Medicine 61, 1821–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB (1991). The social self: on being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar]

- Burns JM, Durkin LA, Nicholas J (2009). Mental health of young people in the United States: what role can the internet play in reducing stigma and promoting help seeking? Journal of Adolescent Health 45, 95–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan SE (2003). Preference for online social interaction a theory of problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being. Communication Research 30, 625–648. [Google Scholar]

- Chung JE (2013). Social interaction in online support groups: preference for online social interaction over offline social interaction. Computers in Human Behavior 29, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar]

- Chung JE (2014). Social networking in online support groups for health: how online social networking benefits patients. Journal of Health Communication 19, 639–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW (1998). The impact of stigma on severe mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 5, 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist 59, 614–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Kosyluk KA, Rüsch N (2013). Reducing self-stigma by coming out proud. American Journal of Public Health 103, 794–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Morris S, Larson J, Rafacz J, Wassel A, Michaels P, Wilkniss S, Batia K, Rüsch N (2010). Self-stigma and coming out about one's mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology 38, 259–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Thompson V, Lambert D, Sangster Y, Noel JG, Campbell J (2003). Perceptions of discrimination among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54, 1105–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree JW, Haslam SA, Postmes T, Haslam C (2010). Mental health support groups, stigma, and self-esteem: positive and negative implications of group identification. Journal of Social Issues 66, 553–569. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Chinman M, Kloos B, Weingarten R, Stayner D, Tebes JK (1999). Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: a review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 6, 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson FB, Sommerville J, Origoni AE, Ringel NB, Parente F (2001). Outpatients with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder: do they differ in their cognitive and social functioning? Psychiatry Research 102, 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L (1995). Effects of homelessness on the quality of life of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46, 922–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M (2015). Mobile Messaging and Social Media 2015. Pew Research Center: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/19/mobile-messaging-and-social-media-2015/

- Entwistle VA, France EF, Wyke S, Jepson R, Hunt K, Ziebland S, Thompson A (2011). How information about other people's personal experiences can help with healthcare decision-making: a qualitative study. Patient Education and Counseling 85, e291–e298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, Gilmer T, Bailey A, Golshan S, Garcia P, Unützer J, Hough R, Jeste DV (2005). Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10 340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. American Journal of Psychiatry 162, 370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT, Drake RE (1997). Physical and sexual assault history in women with serious mental illness: prevalence, correlates, treatment, and future research directions. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23, 685–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen K, Deschaine M, Gruttadara D, Markey D (2012). Young adults with mental health conditions and social networking websites: seeking tools to build community. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 35, 245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haker H, Lauber C, Rössler W (2005). Internet forums: a self-help approach for individuals with schizophrenia? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 112, 474–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey KJ, Brown B, Crawford P, Macfarlane A, McPherson A (2007). ‘Am I normal?’ Teenagers, sexual health and the internet. Social Science & Medicine 65, 771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hert M, Cohen D, Bobes J, Cetkovich-Bakmas M, Leucht S, Ndetei DM, Newcomer JW, Uwakwe R, Asai I, Moller H-J (2011). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry 10, 138–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Borum R, Wagner HR (1999). Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50, 62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highton-Williamson E, Priebe S, Giacco D (2015). Online social networking in people with psychosis: a systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 61, 92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan K, Salzer MS, Solomon P, Brusilovskiy E, Cousounis P (2011). Internet peer support for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: a randomized controlled trial. Social Science & Medicine 72, 54–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp S (2015). Digital, social and mobile worldwide in 2015. We Are Social: http://wearesocial.net/blog/2015/01/digital-social-mobile-worldwide-2015/

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand S-LT, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 60, 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummervold PE, Gammon D, Bergvik S, Johnsen J-AK, Hasvold T, Rosenvinge JH (2002). Social support in a wired world: use of online mental health forums in Norway. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 56, 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam JA, Rosenheck R (1998). The effect of victimization on clinical outcomes of homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49, 678–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder S, Chester A, Castle D, Dodd S, Gliddon E, Berk L, Chamberlain J, Klein B, Gilbert M, Austin DW (2015). A randomized head to head trial of MoodSwings.net.au: an internet based self-help program for bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 171, 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor A, Kirakowski J (2014). Online support groups for mental health: a space for challenging self-stigma or a means of social avoidance? Computers in Human Behavior 32, 152–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman R, Wadley G, Gleeson J, Bendall S, Álvarez-Jiménez M (2014). Moderated online social therapy: designing and evaluating technology for mental health. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI) 21, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, Phelan JC, Nuttbrock L (1997). On stigma and its consequences: evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe P, Powell J, Griffiths F, Thorogood M, Locock L (2009). “Making it all normal”: the role of the internet in problematic pregnancy. Qualitative Health Research 19, 1476–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrane K (2013). The rise of the mobile-only user. Harvard Business Review: https://hbr.org/2013/05/the-rise-of-the-mobile-only-us/

- McKenna KY, Bargh JA (1998). Coming out in the age of the Internet: identity “demarginalization” through virtual group participation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75, 681–694. [Google Scholar]

- Miller BJ, Stewart A, Schrimsher J, Peeples D, Buckley PF (2015). How connected are people with schizophrenia? Cell phone, computer, email, and social media use. Psychiatry Research 225, 458–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Tessner KD, Walker EF (2007). Elevated social Internet use and schizotypal personality disorder in adolescents. Schizophrenia Research 94, 50–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo PK, Coulson NS (2010). Empowering processes in online support groups among people living with HIV/AIDS: a comparative analysis of ‘lurkers’ and ‘posters’. Computers in Human Behavior 26, 1183–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD (1997). Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: global burden of disease study. The Lancet 349, 1498–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano MA, Hayes S, Bennett GG, Ives AK, Foster GD (2013). Using Facebook and text messaging to deliver a weight loss program to college students. Obesity 21, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund JA, Grande SW, Aschbrenner KA, Elwyn G (2014). Naturally occurring peer support through social media: the experiences of individuals with severe mental illness using YouTube. PloS ONE 9, e110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Barre LK, Bartels SJ (2015a). Feasibility of popular m-Health technologies for activity tracking among individuals with serious mental illness. Telemedicine and e-Health 21, 213–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Marsch LA, McHugo GJ, Bartels SJ (2015b). Crowdsourcing for conducting randomized trials of Internet delivered interventions in people with serious mental illness: a systematic review. Contemporary Clinical Trials 44, 77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund JA, Marsch LA, McHugo GJ, Bartels SJ (2015c). Emerging mHealth and eHealth interventions for serious mental illness: a review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health 24, 321–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr H (2008). Mental Health and Social Space: Towards Inclusionary Geographies? Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, Hosman C, McGuire H, Rojas G, van Ommeren M (2007). Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 370, 991–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry BL, Pescosolido BA (2015). Social network activation: the role of health discussion partners in recovery from mental illness. Social Science & Medicine 125, 116–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2014). Emerging Nations Embrace Internet, Mobile Technology. Pew Research Center: http://www.pewglobal.org/2014/02/13/emerging-nations-embrace-internet-mobile-technology/

- Pompili M, Lester D, Innamorati M, Tatarelli R, Girardi P (2008). Assessment and treatment of suicide risk in schizophrenia. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 8, 51–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell J, McCarthy N, Eysenbach G (2003). Cross-sectional survey of users of Internet depression communities. BMC Psychiatry 3, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RachBeisel J, Scott J, Dixon L (1999). Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: a review of recent research. Psychiatric Services 50, 1427–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Thrul J, Delucchi KL, Ling PM, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ (2015). The Tobacco Status Project (TSP): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of a Facebook smoking cessation intervention for young adults. BMC Public Health 15, 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raupach JC, Hiller JE (2002). Information and support for women following the primary treatment of breast cancer. Health Expectations 5, 289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrank B, Sibitz I, Unger A, Amering M (2010). How patients with schizophrenia use the Internet: qualitative study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 12, e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Goodale LC, Dykstra DM, Stone E, Cutsogeorge D, Operskalski B, Savarino J, Pabiniak C (2011). An online recovery plan program: can peer coaching increase participation? Psychiatric Services 62, 666–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A (2015). U.S. smartphone use in 2015. Pew Research Center: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015/

- Smith DJ, Griffiths E, Poole R, Di Florio A, Barnes E, Kelly MJ, Craddock N, Hood K, Simpson S (2011). Beating bipolar: exploratory trial of a novel internet-based psychoeducational treatment for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 13, 571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal J, Messias E, Dickerson FB, Kreyenbuhl J, Brown CH, Goldberg RW, Dixon LB (2004). Comorbidity of medical illnesses among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192, 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinzy Y, Nitzan U, Becker G, Bloch Y, Fennig S (2012). Does the Internet offer social opportunities for individuals with schizophrenia? A cross-sectional pilot study. Psychiatry Research 198, 319–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd NJ, Jones SH, Hart A, Lobban FA (2014). A web-based self-management intervention for bipolar disorder ‘Living with Bipolar’: a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders 169, 21–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomes N (2006). The patient as a policy factor: a historical case study of the consumer/survivor movement in mental health. Health Affairs 25, 720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CH, Taal E, Seydel ER, van de Laar MA (2008). Self-reported differences in empowerment between lurkers and posters in online patient support groups. Journal of Medical Internet Research 10, e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Uden-Kraan CF, Drossaert CH, Taal E, Seydel ER, van de Laar MA (2009). Participation in online patient support groups endorses patients’ empowerment. Patient Education and Counseling 74, 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Demler O, Kessler RC (2002). Adequacy of treatment for serious mental illness in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 92, 92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R, Campbell RD (2014). Stigma, agency and recovery amongst people with severe mental illness. Social Science & Medicine 107, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebland S, Wyke S (2012). Health and illness in a connected world: how might sharing experiences on the internet affect people's health? Milbank Quarterly 90, 219–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]