Abstract

Relatively little is known about young people’s interpretations of sexual behaviour in Latin America. In this study, we examine the most commonly perceived consequences of first sexual intercourse among Mexican middle and high school students, how perceived consequences differ by gender, and factors that may predict experiencing more positive or negative consequences. Sexually active Mexican students aged 12–19 years (N = 268) reported whether they had experienced each of 19 consequences following first intercourse. Both positive consequences, such as physical satisfaction and closeness to partner, and negative consequences, such as worry about STDs and pregnancy, were common. Sex with a non-relationship partner was associated with fewer positive and more negative consequences, with the effect for positive consequences being stronger for young women. Pressure to have sex was associated with fewer positive consequences of first intercourse, and pressure to remain a virgin was associated with more positive and negative consequences. These findings suggest that young people often report mixed feelings about their first sexual intercourse, and that relationship context and sexual socialisation influence their perceptions of the event.

Keywords: Sexual behaviour, First intercourse, Consequences of sex, Young people, Mexico

A growing literature on adolescent sexual behaviour has moved beyond studying health risks to understanding the psychological experience of sexual behaviour (Tolman and McClelland 2011). For example, understanding perceptions of sexual behaviour is important, as these perceptions may influence individuals’ mental health, as well as their future sexual decision-making (Vasilenko, Lefkowitz, and Welsh 2014). Much of the literature on perceived consequences of sexual behaviour has focused on the USA; however, socio-ecological frameworks point to the importance of considering the cultural context in which individuals are embedded (Bronfenbrenner 2005). For example, in Mexico, the influence of the Catholic Church and specific cultural values such as machismo and marianismo may provide gender-specific guidelines about the appropriateness of sexual behaviour that could influence how individuals feel about their first sexual experiences (Arciniega, Anderson, Tovar-Blank, and Tracey 2008; Gil and Vasquez 1996). Thus, we examine the most commonly perceived consequences of first sexual intercourse among Mexican middle and high school students, how perceived consequences of sexual behaviour may differ by gender, and factors that may predict experiencing more positive or negative consequences.

In the USA, much of the research on the experience of first intercourse has focused on gender differences. A body of literature, much of it from the 1990s, found that girls and young women generally report more negative feelings, such as guilt, pain and lack of orgasm or satisfaction, compared to boys and young men (Darling, Davidson, and Passarello 1992; Guggino and Ponzetti 1997; Sprecher, Barbee and Schwartz 1995; Tsui and Nicoladis 2004). Some of these differences may be due to sexual double standards, which suggest that sex, particularly outside of marriage or committed relationships, is more acceptable for men than women (Crawford and Popp 2003), whereas others, such as pain, may be accounted for by physical differences. More recent research, however, has presented a more nuanced picture. Although rates of some specific consequences (e.g., lack of satisfaction) may be higher among young women than young men, young women still report primarily positive consequences, and their overall evaluations of first intercourse may not be significantly different than those of young men (O’Sullivan and Hearn 2008; Smiler et al. 2005; Tsui and Nicoladis 2004).

In contrast, less is known about the experience of first intercourse in Mexico, particularly positive aspects, as research on Mexican adolescents’ sexual behaviour has focused primarily on prevention of risk behaviours (Campero et al. 2011; Pick, Givaudan, and Poortinga 2003). As ecological theories suggest, cultural factors may influence individuals’ feelings about their sexual behaviour (Bronfenbrenner 2005). The majority of Mexican young people aged 12 to 29 are, at least nominally, Roman Catholic (Gobierno Federal 2010), and the prevalence of a religion that prohibits pre-marital sex could lead individuals to feel more guilt about sexual behaviour (Pick et al. 2003). In particular, virginity at marriage is emphasised for women, whereas men feel less religious pressure to abstain from sex (Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). In Mexico, cultural values of marianismo and machismo may shape perceptions of sexual experiences in a highly gendered way. Machismo emphasises sexual dominance by men, whereas marianismo emphasises women’s sexual passivity and purity, with sex reserved for marriage (Arciniega et al. 2008; Gil and Vasquez 1996). Thus, Mexican men may be encouraged or praised for engaging in premarital sexual behaviour or even having children out of wedlock, whereas expressing sexual desire may be discouraged for Mexican women (Pick et al. 2003). Because of these strong differences in sexual expectations for men and women in Mexico, women may experience more negative consequences, such as guilt and regret. Men may also experience negative consequences as a result of sex in situations where they were pressured into sex by other male peers in order to prove their masculinity.

Retrospective qualitative studies have examined feelings about sexuality, virginity and virginity loss among Mexican adults, and findings reflect the influence of Catholicism, machismo, and marianismo. For example, studies have found that although not always practised, virginity until marriage was perceived as an ideal for women that was better for the community and highly promoted by family members (Amuchástegui 1998; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005; Stern 2007). Part of this pressure to remain a virgin may have been tied to gendered economics, in that in the past women who were not virgins were seen as less likely to find a marriage partner who could support them (Amuchástegui 1998; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). Findings from qualitative studies suggest some remnants of this reasoning; for example, many women interviewed in a study revealed a belief that virginity until marriage would lead to a more stable and agreeable relationship than a marriage in which the woman had engaged in premarital sex (Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). Thus, it is possible that women’s sexuality in Mexico, even for girls, may be linked more to ideas of motherhood and reproduction than sexual desire or pleasure (Tuñon Pablos and Eroza Solana 2001). In low income urban areas, girls not only may need to remain a virgin, but may also feel the pressure to act ‘pure’ and be considered ‘good girls’ in order to gain the respect of men, their family members, and society in general (Stern 2007). Thus, women may often feel guilt and shame about their first (premarital) sexual experiences within cultural contexts that endorse high levels of marianismo.

Men, on the other hand, felt little pressure to abstain from premarital sex; instead, they often felt pressure from peers or family to prove their masculinity by engaging in sexual behaviour at an early age (Aguilera et al. 2004; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005; Stern 2007; Tuñon Pablos and Eroza Solana 2001). Consequently, many Mexican men’s experience of first sex was part of an initiation by older male friends or family members that often occurred with a sex worker, rather than an event they fully wanted to engage in (Amuchástegui and Aggleton 2007; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). These initiation experiences were primarily described as negative, whereas sexual experiences with a girlfriend were more often described as intimate and loving (Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). However, the emphasis on female virginity may also lead to negative feelings about first sexual experiences for boys or men who engage in sexual behaviour with a romantic partner, as they may feel guilty about their partner no longer being a virgin (Amuchástegui and Aggleton 2007). Adolescent boys reporting on first sexual experience with their girlfriend were more likely to experience feeling guilty or that they were hurting their partner compared to boys who had first sex with a non-romantic partner (Aguilera, et al. 2004).

Despite these largely negative portrayals of first sexual experiences for both men and women in Mexico, there is some evidence that the negative, highly gendered views of sexual behaviour may be changing or may not be uniform across all of the country. Age of marriage has been rising in Mexico, with an average age of first marriage 27 for women and 29 for men in 2012 (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia 2015). Women’s increasing employment outside the home has given rise to changing surrounding marriage and family relationships (Amuchástegui and Aggleton 2007). Cultural values like marianismo and machismo may be increasingly seen as outdated among youth today, as attitudes are increasingly being shaped by global forces (Carrillo 2010; Gutman 1996). Sexual activity and promiscuity are seen as less central to masculinity, and romantic love is becoming seen as more central to sexual behaviour (Gutman 2006). In addition, there may be less emphasis on virginity due to increased contraceptive use and thus the ability to avoid pregnancy (Gutman 1996). In addition, Mexico is a heterogeneous nation with considerable differences between urban and rural areas. Regional differences in sexual attitudes and behaviours have been documented, with individuals in urban areas viewing sexual behaviour in a less gendered way and sex within a close, non-marital relationship as more acceptable. One qualitative study of men in Mexico City found no examples of men who experienced first intercourse through initiation with a sex worker (Gutman 1996). First sexual experiences with a girlfriend or acquaintance may be more common among men living in cities, in part because the greater economic opportunities for women in more urban areas make them more able to support themselves, and thus have less need to preserve their virginity in order to be a suitable marriage partner (Gonzalez-Lopez 2005; Gutman 1996). Women in urban areas, as opposed to rural areas, are more likely to consider having sex if it occurs in the context of a romantic relationship (Rojas and Castrejón 2011). Thus, regional differences and changing cultural norms suggest that some individuals in Mexico may have more positive first sexual experiences than previously suggested.

Although much of the research on this topic has focused on retrospective adult reports, there are a few qualitative studies focusing on adolescents’ sexual experiences (Aguilera et al. 2004; Stern, 2007; Tuñon Pablos and Eroza Solana 2001). One qualitative study in Mexico City provides some evidence for more nuanced feelings about sex and virginity (Aguilera et al. 2004). Some girls and boys felt that it was particularly important for women to maintain their virginity, while others claimed that both men and women should remain a virgin until marriage. In contrast, there were both girls and boys in the study who felt that it did not matter whether a woman was a virgin, as long as partners loved each other. Although girls in the study frequently mentioned feelings of guilt, shame, regret, and fear of pregnancy in regards to their first sexual experience, they also discussed positive aspects such as curiosity and a desire to have sex (Aguilera et al. 2004). These findings suggest that experiences of first intercourse in Mexico may vary, and future research is necessary to understand these differences and what factors may be associated with more positive or negative perceptions and consequences.

Thus, several gaps in the literature exist in regards to understanding the first sexual intercourse perceptions and experiences of young people in Mexico. Prior retrospective qualitative research on Mexican sexuality suggests that negative first sexual experiences may be common due to gendered cultural expectations, but that attitudes toward virginity may be changing in a way that may lead to more positive first sexual experiences (Aguilera et al. 2004; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). However, much of this research is focused on young adults’ retrospective reports of first experiences. Less research has been conducted with adolescents, or within the last decade. Thus, little is known about how today’s young people experience their sexual behaviour. In addition, to our knowledge there have been no quantitative studies of the perceived consequences of first intercourse in Mexico, and thus it is unclear how common certain consequences are and what factors predict these consequences.

In this study, we examined the prevalence of positive and negative consequences of first sexual intercourse among middle and high school students in Puebla, the fifth largest city in Mexico (Censo de Poblacion y ivienda 2010). Guided by a socio-ecological framework (Bronfenbrenner 2005), we examined whether socio-cultural (religion, pressure to have sex, pressure to remain a virgin) and event-related factors (age at first sex, condom use, relationship with sexual partner) were associated with the positive and negative consequences experienced, and whether gender moderated these associations. Based on past qualitative research conducted in Mexico, several hypotheses were developed. We predicted that, due to the cultural pressure to remain a virgin until married (marianismo) in Mexico, female students would report fewer positive and more negative consequences than male students. We also predicted that the association between contextual factors such as early sex, sex without a condom, being Catholic, and feeling more pressure to remain a virgin would be more strongly associated with negative consequences for female compared to male students. Due to the influence of machismo which emphasises sexual virility for men, we predicted that feeling pressure to have sex would assert a stronger effect on consequences of first sex for male students, and that male students may feel particularly negative about non-relationship sex because the activity was motivated by societal and peer pressure than a romantic desire or individual choice.

Method

Participants

Data derive from a study conducted in public middle and high schools in Puebla, Mexico (Espinosa-Hernandez, Vasilenko, and Bamaca-Colbert 2015). We used data from the second cohort, who were asked questions about consequences of first sexual intercourse. (N = 1,123). We focus on the 24% of students who reported having sex (N = 268). The students in this sub-sample were 56% male, with an average age of 16.0 (SD = 1.5, range 12–19), 60% reported living with both of their parents, and 47% reported being a currently practising Catholic.

Procedures

We contacted principals of two public middle schools and one public high school in Puebla. These schools were co-educational and not religious, which is the norm for public schools in Mexico. The principal investigator of the larger study explained the study protocol to each principal, who approved the study. Students were invited to participate in their classrooms a few days before questionnaires were distributed. Principals chose the classrooms that we invited to participate based on convenience (e.g., exam or class schedules). The procedures approved by the institutional review board at the University of North Carolina, Wilmington, were followed in all schools, and a waiver of active parental consent was obtained from the IRB. School staff distributed forms to students to take home to parents, and separated students whose parents did not allow them to participate. The principal investigator administered the surveys, and classroom teachers helped to proctor the survey. Students completed the survey in the classroom during class time in about an hour and a half and received candy for completing the survey. Students were assured of confidentiality, and all contact information was kept separately from the survey responses.

Measures

The questionnaire was originally written in English, drawing from a number of established measures as described below. Items were then translated from English to Spanish by a committee of researchers and undergraduate research assistants who were either native Spanish speakers or bilingual. Items were then reviewed by two Mexican middle school students and a Mexican school psychologist to ensure grade level was adequate and items were easy to understand by a native Spanish speaker. All participants answered the questionnaire in Spanish. Descriptive statistics of study variables by gender are presented in Table 1, and correlations between predictors are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables by Gender

| Total | Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.95 (1.47) | 15.79 (1.45) | 16.13 (1.47) |

| Catholic | 47.4 | 44.9 | 50.9 |

| Pressure to Have Sex | 1.56 (0.93) | 1.70 (1.02) | 1.38 (0.77) |

| Pressure to Remain a Virgin | 1.64 (1.04) | 1.45 (0.90) | 1.90 (1.19) |

| Age at First Sex | 14.64 (1.60) | 14.32 (1.61) | 15.01 (1.49) |

| Non-use of condom | 23.1 | 28.8 | 25.2 |

| Non-relationship Partner | 21.5 | 30.6 | 10.4 |

| Stranger | 5.5 | 6.6 | 4.2 |

| Friend | 16.0 | 24.0 | 6.3 |

| Relationship Partner | 78.5 | 69.4 | 89.6 |

| Casual Dating Partner | 16.4 | 15.7 | 16.7 |

| Regular Dating Partner | 55.7 | 49.6 | 63.5 |

| Engaged/Living With Partner | 6.4 | 4.2 | 9.3 |

Note. Percentages are presented for categorical variables and means and standards deviations (in parentheses) are presented for continuous variables.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Positive and Negative Consequences and Predictors, by Gender

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive Consequences | −.04 | .12 | −.18 | .09 | .06 | −.37** | −.14 | |

| 2. Negative Consequences | .23* | .08 | .10 | .31** | −.19 | .15 | .14 | |

| 3. Catholic | .05 | .04 | −.05 | −.05 | −.04 | .03 | .19 | |

| 4. Pressure to Have Sex | −.09 | .13 | −.04 | .24* | −.34** | .10 | .18 | |

| 5. Pressure to Remain a Virgin | .03 | .29** | −.07 | .40** | −.00 | −.20 | −.06 | |

| 6. Age at First Sex | .08 | −.10 | .11 | −.26** | −.14 | −.17 | −.10 | |

| 7. Non-relationship Partner | −.23* | .13 | −.05 | .21* | .10 | −.10 | .32** | |

| 8. Non-use of condom | −.09 | −.09 | .09 | .01 | −.05 | −.02 | .40** |

Note: Below diagonal = male, above diagonal = female.

Outcomes

All participants answered the item ‘Have you ever had sex?’ with sex defined as ‘Sex in which the penis penetrates the vagina’. Students who reported having vaginal sex were asked whether they experienced seven positive and twelve intrapersonal and interpersonal consequences (Vasilenko, Lefkowitz and Maggs 2012; see Tables 3 and 4 following for items). These items were assessed separately in the first stage of analyses, and positive and negative sum scores were calculated for the second stage.

Table 3.

Percentage of Students Reporting Positive Consequences of their First Sexual Intercourse, by Gender

| Positive Intrapersonal Consequences | Total Sample | Male | Female | X2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any positive intrapersonal consequence | 81.8 | 86.3 | 75.5 | * |

| Feel physically satisfied | 64.0 | 67.0 | 60.0 | NS |

| Feel better or cheered up | 61.7 | 64.8 | 57.2 | NS |

| Feel a thrill or rush | 54.1 | 56.0 | 51.4 | NS |

| Feel attractive or better about yourself | 43.1 | 44.2 | 58.6 | NS |

| Positive Interpersonal Consequences | ||||

| Any positive interpersonal consequence | 77.8 | 77.8 | 77.2 | NS |

| Feel intimate or closer to partner | 63.2 | 58.1 | 69.7 | * |

| Feel you avoided annoying or angering your partner | 37.2 | 46.9 | 24.3 | * |

| Feel you enhanced your reputation | 24.2 | 32.1 | 13.3 | *** |

Note: X2 indicates whether there are significant gender differences in reporting given consequence.

NS = not significant.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Table 4.

Percentage of Students Reporting Negative Consequences of their First Sexual Intercourse, by Gender

| Negative Intrapersonal Consequences | Total Sample | Male | Female | X2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any negative intrapersonal consequence | 83.1 | 81.5 | 84.8 | NS |

| Worry about pregnancy | 58.9 | 56.3 | 63.7 | NS |

| Worry you were exposed to another STD | 52.4 | 51.4 | 52.4 | NS |

| Worry you were exposed to HIV/AIDS | 50.8 | 50.7 | 51.0 | NS |

| Not enjoy it | 47.2 | 45.7 | 49.3 | NS |

| Worry your parents may find out | 46.1 | 34.0 | 63.6 | *** |

| Experience any discomfort or pain | 36.2 | 22.6 | 56.8 | *** |

| Feel you went against your morals or ethics | 28.0 | 24.8 | 31.3 | NS |

| Wish you had not had sex | 22.8 | 22.0 | 22.5 | NS |

| Negative Interpersonal Consequences | ||||

| Any negative interpersonal consequence | 71.7 | 72.2 | 70.1 | NS |

| Feel like things moved too fast | 44.7 | 40.4 | 50.0 | *** |

| Worry your partner wants more commitment | 38.3 | 45.7 | 29.1 | * |

| Worry another partner could find out | 36.4 | 38.5 | 34.7 | NS |

| Feel you harmed your reputation | 24.8 | 23.6 | 25.9 | NS |

Note: X2 indicates whether there are significant gender differences in reporting given consequence.

NS = not significant.

p < .05,

p< .01,

p < .001.

Predictors

Four predictors assessed more general characteristics or values. Gender was assessed by self-report (0 = female, 44%; 1 = male, 56%). Whether an individual currently identified as Catholic was measured by a series of questions, the first asking if the participant currently practised a religion, with a follow-up open-ended question asking what religion (47.4% reported being a practising Catholic). This measure had been used in prior research on religion and sexual behaviour in Mexico (Espinosa-Hernandez, Bissel-Havran, and Nunn 2015). Pressure to have sex was assessed by a single item ‘How much pressure have you received from others to have sex?’ rated on a 4 point scale from ‘A lot’ to ‘None’ (M = 1.56, SD = .93). Pressure to remain a virgin was assessed with the item ‘How much pressure have you received from others to remain a virgin?’ rated on a 4 point scale from ‘A lot’ to ‘None’ (M = 1.64, SD = 1.04). These two measures were adapted from those used in prior research (Sprecher and Regan 1996). They were reverse coded so higher scores indicated more pressure, and were centred at the sample’s mean score for analyses.

Three predictors assessed situational factors of the sexual experience, and were only asked to participants who had reported engaging in sexual behaviour. Age at first intercourse was a single item, ‘At what age did you first have sex?’ Scores ranged from ages 8 to 18 (M = 14.64, SD = 1.60). Non-relationship sex was assessed by a single item with 7 response options asking ‘How would you describe the person you had sex with this first time?’, similar to categories used in prior research (Vasilenko, Lefkowitz and Maggs 2012). We recoded this item to a dichotomous measure of relationship versus non-relationship sex (0 = living with or engaged, regular dating partner or casual dating partner 78.5%; 1 = friend or stranger, 21.5%). Non-use of contraception was assessed with a single item asking ‘Did you use any method of contraception/birth control when you had sex this first time?’ and was recoded so that 0 = contraception used (73%) and 1 = no contraception used (27%).

Analytic Plan

First, we examined frequencies of reporting each of the 19 consequences, for the whole sample and separately by gender. Second, we tested for gender differences in reporting each consequence using X2 tests. Finally, we examined predictors of the number of positive and negative consequences reported using ordinary least squares regression. We ran models in three steps. First, we examined the main effects of our 7 predictors, and then added interactions of gender and the predictors to test for moderation. Finally, in cases where gender interactions were not significant, we removed the non-significant interactions to arrive at a final model.

Results

Both positive and negative consequences were frequently reported (see Table 3 for positive, Table 4 for negative), and positive and negative consequences were positively correlated (see Table 2). On average, participants reported 4.0 positive consequences (SD = 1.79) and 5.24 negative consequences (SD = 3.01). The most commonly reported positive consequences were feeling physically satisfied (64.0%), feeling intimate or closer to partner (63.2%), and feeling better or cheered up (61.7%). The most commonly reported negative consequences were worry about pregnancy (58.9%), sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (52.4%), and HIV (50.8%).

We then ran χ2 tests on each item to examine how rates of reporting consequences differed by gender. Significant gender differences were found for 7 of 19 items, and most were in the direction predicted by sexual double standards. For example, female students were less likely than male students to feel that sex had enhanced their reputation or worry that their partner wanted more commitment. In addition, female students were more likely than male students to feel that things moved too fast, experience pain, worry that their parents would find out, and feel close to their partner. However, male and female students were equally likely to report the majority of consequences, including physical satisfaction, regret, going against morals or ethics, and worry about pregnancy and STDs.

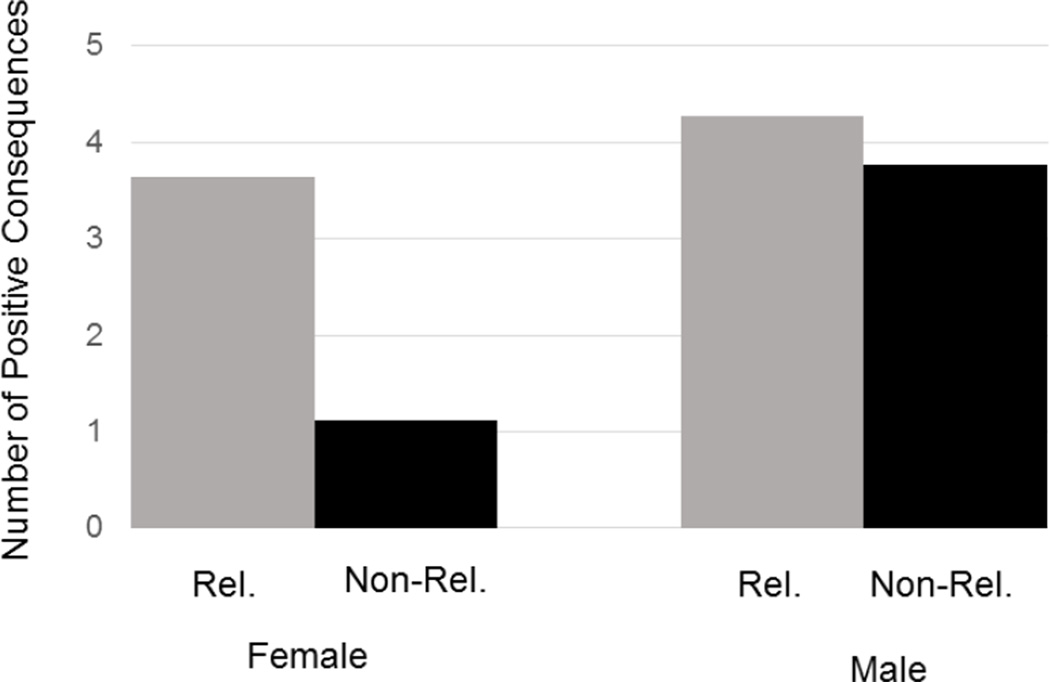

We then examined predictors of positive consequences (Table 5). In the final model, being male was associated with any average of 1 additional positive consequence. Feeling pressure to have sex was associated with fewer positive consequences of first intercourse, and feeling pressure to remain a virgin was associated with more positive consequences. Non-relationship sex was associated with fewer positive consequences, and this association was stronger for female compared to male students (see also Figure 1).

Table 5.

Predictors of Number of Positive Consequences of First Sex Among Mexican Middle and High School Students

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Final | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercepta | 3.51*** | .25 | 3.59*** | .32 | 3.64*** | .25 |

| Individual Factors | ||||||

| Male | 0.93** | .27 | 0.72 | .41 | 0.63 | .29 |

| Catholic | 0.26 | .25 | 0.37 | .39 | 0.29 | .25 |

| Pressure to Have Sex | −0.38* | .15 | −.39 | .27 | −.38* | .15 |

| Pressure to Remain a Virgin | 0.33** | .13 | 0.28 | .16 | 0.28* | .12 |

| Event Contextual Factors | ||||||

| Age First Sex | 0.67 | .41 | 0.04 | .14 | 0.05 | |

| Non-relationship | −0.93** | .33 | −2.59*** | .71 | −2.53*** | |

| Non-use of condom | −0.08 | .29 | 0.5 | .47 | ||

| Gender Interactions | ||||||

| Catholic × Male | −0.15 | .51 | ||||

| Pressure to Have Sex × Male | 0.02 | .33 | ||||

| Pressure Virgin × Male | 0.01 | .26 | ||||

| Age First Sex × Male | 0.02 | .17 | ||||

| Non-relationship × Male | 2.09* | .80 | 2.02** | .75 | ||

| Non-use of condom × Male | −.13 | .60 | ||||

Note: Model 1 R2 = .15, Model 2 R2 = .19, Final Model R2 = .19.

Intercept refers to female students in model 1, and female students who used a condom, had first sex with a relationship partner, were not Catholic, and had mean scores on all other items.

Figure 1.

Results of significant interaction estimating number of positive consequences of first intercourse reported by female and male students, by relationship with first sexual partner. Rel. = relationship, Non-Rel.,= non-relationship.

Finally, we examined predictors of negative consequences (Table 6). Because there were no significant gender interactions in this model, our final model is the same as our model with main effects only (Model 1). Being male was associated with reporting 1.5 fewer negative consequences. Feeling pressure to remain a virgin and having non-relationship sex were associated with more negative consequences.

Table 6.

Predictors of Number of Negative Consequences of First Sex Among Mexican Middle and High School Students

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Intercepta | 5.58*** | .41 | 5.58 | .41 |

| Individual Factors | ||||

| Male | −1.50** | .44 | −1.51*** | .44 |

| Catholic | 0.69 | .42 | 0.21 | .64 |

| Pressure to Have Sex | −0.03 | .27 | −.03 | .45 |

| Pressure to Remain a Virgin | 0.99*** | .22 | 0.99*** | .28 |

| Event Contextual Factors | ||||

| Age First Sex | −0.09 | .14 | −.09 | .23 |

| Non-relationship | 1.14* | .57 | 1.37 | 1.14 |

| Non-use of condom | −0.34 | .50 | 0.57 | .81 |

| Gender Interactions | ||||

| Catholic × Male | 0.84 | .84 | ||

| Pressure to Have Sex × Male | −0.34 | .58 | ||

| Pressure Virgin × Male | −0.12 | .45 | ||

| Age First Sex × Male | 0.02 | .29 | ||

| Non-relationship × Male | −0.12 | 1.32 | ||

| Non-use of condom × Male | −1.63 | 1.04 | ||

Note: Model 1 R2 = .22, Model 2 R2 = .21. Because Model 2 had no statistically significant interactions, we interpret model 1 as our final model.

Intercept refers to female students who used a condom, had first sex with a relationship partner, were not Catholic, and had mean scores on all other items.

Discussion

These findings suggest that Mexican students perceive both positive and negative consequences following their first sexual intercourse experience. The majority of students reported consequences such as feeling satisfied, cheered up, and close to their partner, suggesting that sex is viewed positively for both male and female students. However, it is also important to note that the majority of participants also reported some negative consequences; specifically, worries about pregnancy, HIV and other STDs were commonly reported. This may be due to the fact that knowledge about condoms and rates of condom use are relatively low among Mexican adolescents (Gayet et al. 2003; Olaíz et al. 2006), which may lead to worry about pregnancy and STDs. Thus, these findings emphasise the importance of delivering prevention programmes that are aimed at increasing condom use and preventing pregnancy.

In addition, our findings point to the importance of considering the socio-ecological context in which individuals are embedded in research on consequences of sexual behaviour (Bronfenbrenner 2005). For example, we observed some gender differences in perceived consequences of sex that suggest the influence of sexual double standards related to machismo and marianismo (Arciniega, et al. 2008; Gil and Vasquez 1996). Consistent with prior research in the USA and Canada (Darling et al. 1992; Guggino and Ponzetti 1997; Sprecher et al. 1995; Tsui and Nicoladis 2004) and qualitative research in Mexico (Amuchástegui 1998; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005; Stern 2007), male participants, on average, reported more positive and fewer negative consequences. Specifically, male students may see sex as more likely to improve their reputation, whereas female students are more likely to see sex as physically painful and relationship-centred. Notably, more than half of female participants were worried that their parents would find out they had sex, whereas less than a third felt that they had gone against their morals or ethics or wished that they had not had sex. Thus, it appears that female students’ negative feelings may be influenced more by external sources than internalised negative messages about sex. While young Mexicans may increasingly consider values such as marianismo as outdated (Carrillo 2010), it is possible that young people who still live at home may continue to be strongly influenced by parents and other authority figures who are less accepting of sexual behaviours, particularly for girls or young women.

Despite these gender differences male and female participants were equally likely to endorse many consequences. For example, there were no gender differences in the odds of feeling physically satisfied, feeling better about one’s self, feeling sex went against morals or ethics, or wishing sex had not occurred. Thus, although there are some gender differences in experiences of first sexual intercourse in Mexican students that may reflect gendered cultural norms, both male and female students report many positive consequences.

Although non-relationship sex was associated with more negative consequences for both male and female participants, it was more strongly associated with a smaller number of positive consequences for female students. This finding is somewhat surprising given prior work on men’s first experiences of non-relationship sex in Mexico, which has suggested that men who engage in first sex with a non-relationship partner often do so with a sex partner as part of an initiation ritual (Amuchástegui and Aggleton 2007; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). This prior research would suggest that women, who are expected to be virgins until marriage, may be distressed by any non-marital sexual behaviour, whereas men may not feel particularly positive about non-relationship sex which may occur in a more coercive and non-romantic context. Only 5% of male participants in this sample engaged in sex with a stranger, and thus they may have engage in non-relationship behaviour in more positive contexts. These findings are more consistent with US research, which has found that women experience many positive consequences of their first sexual experience, but that non-relationship sex is associated with fewer positive consequences (Higgins et al. 2010; Sprecher et al. 1995). It is possible that Mexican young people’s sexuality is increasingly shaped by values from the USA and other western nations, in which sex is more acceptable in general, although non-relationship sex is seen as particularly problematic for women (Crawford and Popp 2008). A more recent qualitative study of Latina girls in the USA found that unlike women from their mother’s generation, girls felt that the loss of virginity was acceptable in contexts in which there were feelings of love or caring with a partner (García 2009). Similarly, Mexican young people may be adopting attitudes about sexual behaviour that are increasingly influenced by romantic rather than traditional values (Gutman 1996).

Several other factors predicted the number of consequences of first intercourse students experienced. Students who felt pressure to have sex reported fewer positive consequences, suggesting that young people who engage in sexual behaviours due to external factors may experience it in a less positive manner. In addition, feeling pressure to remain a virgin was associated with a larger number of both positive and negative consequences of first sex. The greater number of negative consequences for those feeling more pressure to remain abstinent is consistent with the idea that individuals who are in a context in which sex is discouraged may feel more guilt, shame or other negative feelings when they become sexually active (Vasilenko et al. 2014).

The finding that that participants who felt greater pressure to remain a virgin experienced more positive consequences may seem counterintuitive. It is possible that individuals who feel pressure to abstain yet still engage in sexual behaviour are highly oriented toward or interested in sex, and thus enjoy sex more and experience more positive consequences. In addition, pressure to remain a virgin may be associated with more supportive or involved parents or peers, which may also be associated with higher relationship satisfaction with partners and more enjoyable sexual experiences. It is also noteworthy that there were no gender differences in these associations. Thus, although cultural pressures generally dictate that men should be highly sexual and women remain a virgin (Arciniega et al. 2008; Gil and Vasquez 1996; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005), it appears that, if they experience these pressures, both male and female students react to them in similar ways.

Some socio-cultural and event-related factors that we examined were not significantly associated with positive or negative consequences. Although being Catholic is associated with a later timing of first intercourse among Mexican middle and high school students (Espinosa-Hernandez, Bissel-Havran, and Nunn 2015), this factor was not associated with positive or negative consequences when students engaged in first intercourse in either bivariate correlations or multivariate models. It is possible that Mexican culture is so strongly influenced by the Catholic Church that individuals internalise similar values about sex regardless of whether or not they are actually Catholic. Research has suggested the influence of Catholicism on attitudes about sexual intercourse has been found across Mexican individuals from different backgrounds (Amuchástegui 1999). Although Mexican women may talk about the need to remain a virgin in ways that echo Catholic teachings, they rarely discuss those attitudes as influence by religion, citing instead the importance of family or community (Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). Alternatively the role of Catholic religion in young people’s sexuality might be not as important as we expected, or it is possible that our measure did not adequately capture this construct (Espinosa-Hernandez, Bissel-Havran, and Nunn 2015). In addition, we found no effect of age, despite research showing that sex at an earlier age is associated with more negative or less positive outcomes in the USA and other industrialised nations (Dickson et al. 1998; Higgins et al. 2010; Sprecher et al. 1995; Walsh et al. 2011). US culture and sexuality education emphasises waiting to have sex until an individual is ‘ready,’ which suggests that sex is normative at certain ages or situations, but more problematic in others (Ashcraft 2006; Haffner 1995). In contrast, Mexican values may have less age-graded expectations, instead emphasising how sex is almost always appropriate for men and only appropriate for women as part of marriage, regardless of age (Amuchástegui 1998; Gonzalez-Lopez 2005). In addition, sexual behaviour at an early age is less common in Mexico compared to the US (Espinosa-Hernandez, Vasilenko, and Bamaca-Colbert 2015), limiting our sample size and the variability in age of first intercourse, which may have led to this null finding. Future research with a larger sample or that followed individuals at older ages could give a fuller picture of the consequences of Mexican individuals’ transition to sexual intercourse at different ages.

There are several other limitations to this study that provide areas for future research. This sample included students from public schools in only one Mexican city, and thus may not be representative of all Mexican students. Research suggests regional variations in contexts of and views about sexual behaviour, and individuals from more rural areas may differ in their timing of first sex, partners, and attitudes about sex in a way that may impact the consequences of their sexual behaviour (Gonzalez-Lopez 2005; Stern 2001). In addition, because our sample is school-based, and young people who engage in early sexual behaviour or become pregnant are more likely to drop out of school (Kattam and Székely 2014), our sample may not be fully representative of all first sexual experiences. The sample of sexually active students was relatively small, limiting our ability to detect interactions. In addition, because of our small sample we were not able to further investigate more nuanced differences by partner type (e.g., stranger, friend, casual partner, regular partner), making this an important are for future research. Our sample was cross-sectional, and thus we cannot be certain about the directionality of associations. In addition, we focused on retrospective reports of an event that could have occurred some time earlier, and thus feelings about first intercourse may have changed over time. As our focus was on perceptions of first intercourse, we do not know how Mexican young people experience later occurrences of sexual behaviour or how these experiences influence their later marriages or relationships.

Despite these limitations, this research extends current knowledge of Mexican young people’s sexual behaviour beyond the current focus on risky sexual behaviour, STDs and unwanted pregnancy, and shows that female and male Mexican middle and high school students perceive both positive and negative consequences of their first sexual experiences. These findings help to better understand normative sexual development among young people in Mexico. In addition, they provide information that may be important for framing sexuality education programmes. Programmes are more likely to be effective if they contain accurate information about a population and their experiences (Rotheram-Borus et al. 2009). Thus, programmes for Mexican students should incorporate information about the potential positive and negative aspects of sexual behaviour. In addition, the findings suggest that Mexican students have a high level of concern about pregnancy and STDs as a result of sexual intercourse, and thus programmes should provide accurate information about contraception and strategies to ensure proper use in order to decrease potential negative consequences of sex.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2013 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Child Development in Seattle, WA. We would like to acknowledge the University of North Carolina, Wilmington Cahill Award to Graciela Espinosa-Hernandez for funding this study and the Social Science Research Institute at Penn State for their research support. We thank Julia Daugherty, Frankie Machado, Rosie Swinehart and Roderick Yow II for help with data collection, as well as Zuilma Hernandez Montes De Oca, the Espinosa-Hernandez family, and the teachers and principals who made data collection possible. Sara Vasilenko was funded by NIDA grants P50-DA010075 and 2T32DA017629-06A1.

References

- Aguilera Rosa María, Romero Martha, Domínguez Mario, Lara Ma Asunción. Primeras Experiencias Sexuales En Adolescents Inhaladores de Solvents: ¿De La Genitalidad Al Erotismo? Salud Mental. 2004;27(1):60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Amuchástegui Ana. Virginity in Mexico: The role of competing discourses of sexuality in personal experience. Reproductive Health Matters. 1998;6(12):105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Amuchástegui Ana. Dialogue and the Negotiation of Meaning: Constructions of Virginity in Mexico. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 1999;1(1):79–93. doi: 10.1080/136910599301175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amuchástegui Ana, Aggleton Peter. ‘I Had a Guilty Conscience Because I Wasn’t Going to Marry Her’: Ethical Dilemmas for Mexican Men in Their Sexual Relationships with Women. Sexualities. 2007;10(1):61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega G Miguel, Thomas C Anderson, Tovar-Blank Zolia G, Tracey Terence J G. Toward a fuller conception of machismo: Development of a traditional machismo and caballerismo scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(1):19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Achcraft Catherine. Ready or Not … ? Teen Sexuality and the Troubling Discourse of Readiness. Anthropology & Education Quarterly. 2006;37(4):328–346. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner Urie. Making human beings human: Bioecological perspective on human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Campero Lourdes, Walker Dilys, Atienzo Erika E, Gutierrez Juan Pablo. Journal of Adolescence. 2. Vol. 34. Elsevier Ltd; 2011. A Quasi-Experimental Evaluation of Parents as Sexual Health Educators Resulting in Delayed Sexual Initiation and Increased Access to Condoms; pp. 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo Héctor. Review of against machismo: Young adult voices in Mexico City, by Josué Ramirez. American Ethnologist. 2010;37(2):410–411. [Google Scholar]

- Censo de Poblacion y Vivienda. Panorama sociodemográfico de Puebla. Mexico INEGI: Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia; 2010. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford Mary, Popp Danielle. Sexual Double Standards: A Review and Methodological Critique of Two Decades of Research. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40(1):13–26. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling Carol Anderson, Davidson J. Kenneth, Passarello Laruen C. The Mystique of First Intercourse Among College Youth: The Role of Partners, Contraceptive Practices and Psychological Reactions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1992;21(1):97–117. doi: 10.1007/BF01536984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson Nigel, Paul Charlotte, Herbison Peter, Silva Phil. First Sexual Intercourse: Age, Coercion, and Later Regrets Reported by a Birth Cohort. BMJ. 1998;316(7124):29–33. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7124.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Hernandez Graciela, Vasilenko Sara A, Bamaca-Colbert Mayra Y. Sexual behaviors in Mexico: The role of values and gender across adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jora.12209. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Hernández Graciela, Bissell-Havran Joanna M, Nunn Anna M. The role of religiousness and gender in sexuality among Mexican adolescents. Journal of Sex Research. 2015 doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.990951. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Lorena. Love At First Sex: Latina Girls’ Meanings of Virginity Loss and Relationships. Identities. 2009;16(5):601–621. [Google Scholar]

- Gayet Cecilia, Juárez Fátima, Pedroza Laura A, Magis Carlos. Uso del condon entre adolescentes mexicanos para la prevencion de las infecciones de transmision sexual. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2003;45(sup 5):5632–5640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil Rosa M, Vazquez Carmen I. The Maria paradox: How Latinas can merge old world traditions with new world self-esteem. New York, New York: Berkley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Federal de Mexico Gobierno. Encuesta Nacional de Juventud 2010: Resultados Generales. 2010 Retrieved from: http://www.imjuventud.gob.mx/imgs/uploads/Encuesta_Nacional_de_Juventud_2010_Resultados_Generales_18nov11.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- González-López Gloria. Erotic journeys: Mexican immigrants and their sex lives. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guggino Julie M, Ponzetti James J. Gender Differences in Affective Reactions to First Coitus. Journal of Adolescence. 1997;20(2):189–200. doi: 10.1006/jado.1996.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann Matthew C. The meanings of macho. Being a man in Mexico City. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Haffner Debra W. Facing Facts: Sexual health for America’s adolescents. New York: Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins Jenny A, Trussell James, Moore Nelwyn B, Davidson J. Kenneth. Virginity Lost, Satisfaction Gained? Physiological and Psychological Sexual Satisfaction at Heterosexual Debut. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47(4):384–94. doi: 10.1080/00224491003774792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografia. Estadisticas de Nupcialidad. 2015 Retrieved from: http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/sisept/Default.aspx?t=mdemo79&s=est&c=23568. [Google Scholar]

- Kattan Raja B, Székely Miguel. Dropout in Upper Secondary Education in Mexico: Patterns, Consequences and Possible Causes. Washington, D.C.: World Bank; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olaíz Gustavo, Rivera Juan, Shamah Teresa, Rojas Rosalba, Villalpando Salvado, Hernández Mauricio, Sepúlveda Jaime. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2006. Cuernavaca: Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan Lucia F, Hearn Kimberly. Predicting First Intercourse among Urban Early Adolescent Girls: The Role of Emotions. Cognition & Emotion. 2008;22(1):168–179. [Google Scholar]

- Pick Susan, Givaudan Martha, Poortinga Ype H. Sexuality and Life Skills Education: A Multistrategy Intervention in Mexico. American Psychologist. 2003;58(3):230–234. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Olga, José Luis Castrejón. Género e iniciación sexual en México. Detección de diversos patrones por grupos sociales. EstudiosDemográficos y Urbanos. 2011;26(76):75–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus Mary Jane, Swendeman Dallas, Flannery Diane, Rice Eric, Adamson David M, Ingram Barbara. Common Factors in Effective HIV Prevention Programs. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(3):399–408. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9464-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiler Andrew P, Ward L Monique, Caruthers A, Merriweather A. Pleasure, Empowerment and Love: Factors Associated with a Positive First Coitus. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2005;2:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher Susan, Barbee A, Schwartz P. ‘Was It Good for You, Too?’: Gender Differences in First Sexual Intercourse Experiences. Journal of Sex Research. 1995;32(1):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher Susan, Regan Pamela C. College Virgins: How Men and Women Perceive Their Sexual Status. The Journal of Sex Research. 1996;33(1):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stern Claudio. Estereotipos de Género, Relaciones Sexuales Y Embarazo Adolescente En Las Vidas de Jóvenes de Diferentes Contextos Socioculturales En México. Estudios Sociológicos. 2007;25(73):105–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui Lily, Nicoladis Elena. Losing It Similarities and Differences in First Intercourse Experiences of Men and Women. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality. 2004;13(2):95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñon Pablos Esparanza, Enrique Eroza Solana. Género y sexualidad adolescente. La búsqueda de un conocimiento huidizo. Estudios Sociológicos. 2001;19(55):209–226. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman Deborah L, McClelland Sara I. Normative Sexuality Development in Adolescence: A Decade in Review, 2000–2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(1):242–255. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko Sara A, Lefkowitz Eva S, Maggs Jennifer L. Short-Term Positive and Negative Consequences of Sex Based on Daily Reports among College Students. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49(6):558–569. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.589101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilenko Sara A, Lefkowitz Eva S, Welsh Deborah P. Is Sexual Behavior Healthy for Adolescents? A Conceptual Framework for Research on Adolescent Sexual Behavior and Physical, Mental, and Social Health. In: Lefkowitz Eva S, Vasilenko Sara A., editors. Positive and Negative Outcomes of Sexual Behaviors. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2014. pp. 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh Jennifer L, Ward L Monique, Caruthers Allison, Merriwether Ann. Awkward or Amazing: Gender and Age Trends in First Intercourse Experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2011;35(1):59–71. [Google Scholar]