Abstract

Older adults in the U.S. and many countries around the world die by suicide at elevated rates compared to younger adults. However, relatively little is known about psychotherapeutic approaches to managing and treating suicide risk among older adults. The patient in this case presented with elevated suicide risk and was treated with Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) informed by the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. This theoretical model proposes that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are causes of suicide ideation. IPT guides therapists to look for one of four interpersonal stressors that may be present in a client’s life – grief, role transitions, interpersonal disputes, and interpersonal sensitivity (i.e., skills deficits). The Interpersonal Theory provides a rationale for choosing one problem focus over another. Specifically, the problem area that allows the therapist and patient to target and ameliorate thwarted belongingness and/or perceived burdensomeness is selected. The positive outcome of reduced suicide risk in this case illustrates how targeting the constructs of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness with Interpersonal Psychotherapy may help older adults resolve suicide ideation and prevent recurrences of suicidal crises.

Keywords: suicide, suicidal ideation, Interpersonal Theory of Suicide, Interpersonal Psychotherapy, older adults

Theoretical and Research Basis for Treatment

Older adults in the U.S. and many countries around the world die by suicide at elevated rates compared to younger adults (Heron et al., 2009; World Health Organization, 2002). In the U.S., this is particularly true for older white men (Heron, et al., 2009). Further, older adults tend to use particularly lethal means when engaging in suicidal behavior (i.e., guns) and are more likely to die on their first attempt compared to younger adults (Conwell, Rotenberg, & Caine, 1990; McIntosh & Santos, 1985). As lifespan continues to increase, an increasing proportion of the world’s population will be made up of older adults (i.e., age 60 or older; United Nations, 2009). In turn, the problem of late-life suicide will increase, as will the number of older adults at risk for suicide that psychologists will see in their practices. However, compared to the magnitude of the problem, relatively little is known about psychotherapeutic approaches to managing and treating suicide risk among older adults. Given differences in clinical presentations and risk factors, we cannot assume that treatments shown to help suicidal younger adults will help older adults. For example, an adaptation of DBT for depressed older adults did demonstrate reductions in depression severity, but suicide ideation and behavior was not reduced (Lynch et al., 2007).

Collaborative care models in primary care have been examined with regards to their effectiveness in the treatment of late-life depression and reduction of suicide ideation. Collaborative care models (CCM’s) include augmenting depression treatment in primary care (or other settings, such as social service agencies) with psychiatric consultation and medication recommendations, psychoeducation for patients, symptom monitoring, and the option of brief psychotherapy that can be delivered by non-mental health specialists (Gilbody, Bower, Fletcher, Richards, & Sutton, 2006). CCM’s that offered Interpersonal Psychotherapy (the PROSPECT trial) and problem-solving therapy (the IMPACT trial) have demonstrated positive benefits for older adults regarding amelioration of suicide ideation (Alexopoulos et al., 2009; Unutzer et al., 2006). However, not all of the patients in these trials received psychotherapy, and disentangling the effect of psychotherapy from the effects due to medications and other components of the treatment package, such as symptom monitoring, is impossible.

Interventions that are associated with reduced suicide rates among older adults are also informative, although none involved psychotherapy. These multi-component interventions involve: 1) telephone-based outreach, evaluation and support services (DeLeo and colleagues’ Telehelp/Telecheck intervention; De Leo, Dello Buono, & Dwyer, 2002; De Leo, Carollo, & Dello Buono, 1995); 2) screening and referral for care, and engagement in health education, volunteer, and peer support activities (Oyama et al., 2008) and, 3) case management, supportive phone calls, psychoeducation, and psychiatric care (Chan et al., 2011). Although it is not possible to identify the key mechanisms of action in these interventions, an element common to all of these interventions—from collaborative care, to Telehelp/Telecheck to supportive phone check-ins—is the promotion of connectedness through relationships with providers or peers. Thus, it is possible that psychotherapies that target the interpersonal domain may be particularly suited to addressing suicide risk among older adults.

In line with this hypothesis, Marnin Heisel and his colleagues proposed that Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) is ideally suited to treat older adults with suicide ideation because these older adults often present with social problem solving deficits and difficulties with interpersonal functioning, both of which are associated with suicide ideation among older adults and are key treatment targets in IPT (Heisel, Duberstein, Talbot, King, & Tu, 2009). Thus, available empirical data indicate a good match between risk factors for late life suicide ideation and the proposed targets and mechanisms in IPT. Preliminary, uncontrolled data from Heisel and colleagues suggest that IPT is a promising approach to the treatment of death ideation (i.e., wishing for one’s death) and suicide ideation (i.e., thinking of killing oneself) in later life: the treatment resulted in significant pre-post reductions in death and suicide ideation, as well as reductions in depression symptom severity (Heisel et al., 2009). Further, other studies indicate that IPT is useful in preventing relapse and maintaining gains in social functioning among older adults with depression (Lenze et al., 2002; Reynolds et al., 1999).

Treatment manuals specifically describing the implementation of IPT with older adults (Hinrichsen & Clougherty, 2006) are available, including a modification for older adults with cognitive impairment (Miller, 2009). However, neither manual specifically addresses case formulation or treatment targets when the presenting problem is suicide risk and/or the clinician wishes to address suicide risk directly rather than indirectly through reduction in depressive symptoms. In the case we describe here, the patient had been hospitalized due to severe suicide ideation, following which he presented for outpatient treatment with mild depressive symptoms, anxiety, and elevated suicide risk. The patient in this case was treated with Interpersonal Psychotherapy informed by the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. This theoretical model (an area of expertise for the clinician, KVO) was used to guide the selection of treatment targets within the IPT model, with consultation from both a psychologist with expertise in IPT (NT) and a geropsychologist (DK).

In brief, the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide proposes that suicide ideation is caused by the feeling that one does not belong to valued relationships or groups combined with the perception that one is a burden on others. The theory proposes that not all who think about suicide are capable of engaging in suicidal behavior; rather, individuals must acquire the capability for suicide by habituating to the fear and pain involved in self-harm, through the experience of physically painful or frightening experiences, such as military combat, gun use, previous suicide attempts, or non-suicidal self-injury, to name just a few examples.

A clinical manual that applies the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide to clinical work with suicidal patients (Joiner, Van Orden, Witte, & Rudd, 2009) was used to guide treatment. This clinical framework assumes that suicide risk will be reduced in therapy by eliminating (or reducing) thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, and addressing the presence of acquired capability. In short, changes in thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are presumed to be the mechanisms of action (or mediators) between the work done in therapy and the outcome of interest, such as reduced suicide risk, reduced suicide/death ideation, or elimination of suicidal behaviors. Acquired capability is presumed to be a stable trait once acquired; thus, in the framework, acquired capability can be blocked from expression, but will always elevate suicide risk. Because acquired capability elevates suicide risk in the presence of any other suicide risk factors (e.g., depressive symptoms, social isolation, family conflict), it can be conceptualized as a moderator of treatment outcome.

This clinical framework emphasizes assessment of the theory’s key constructs—thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability for suicide—and using that information to guide the selection of clinical focus in IPT, as well as degree of improvement and readiness for termination. A key aspect of IPT is the collaborative selection of one (or potentially two) “problem areas” – role transitions, interpersonal disputes, grief, or interpersonal sensitivity (or deficits) – as the treatment focus. These problem areas map quite well onto the types of stressors that older adults may be experiencing that lead to suicidal crises. First, the grief problem area could be useful for an older adult whose presenting problem is a suicidal crisis in the context of spousal bereavement. In this case, the therapist might hypothesize that feelings of thwarted belongingness contributed to the suicidal crisis and would proceed to investigate that hypothesis in order to help the client decide on the problem area. Another scenario we have seen clinically is an older adult presenting with the role transition as their relationships with adult children change from parent/caregiver to care receiver in the context of increasing functional impairment. In this instance, some older adults develop beliefs that they are a burden on their family and develop death and suicide ideation. Another common scenario is an older adult who presents with a suicidal crisis in the context of increasing social isolation. In this instance, the therapist would assess for presence of and causes of thwarted belongingness. If social anxiety or social skills deficits appear to be primary contributors to social isolation, the interpersonal sensitivity problem area could be recommended to the client. Finally, the interpersonal disputes area can be useful for older adults presenting with feelings that they are a burden on significant others in the context of family conflict. This final scenario is the clinical context for the current case, to which we now turn.

Case Introduction

“Thomas” is a 68-year old divorced, white male, who at the start of therapy lived with an opposite sex roommate in his home in a suburb of a mid-sized city. He was referred to a geriatric mental health outpatient clinic for psychotherapy after an inpatient hospitalization for suicide ideation with a plan to shoot himself with a pistol. The psychiatrist on the inpatient unit noted that the patient’s depressed mood and acute anxiety appeared to be caused by both recent and chronic psychosocial stressors, including conflicts with his adult sons and grief over the loss of his parents. For these reasons, and the fact that Thomas’ mood improved rapidly while on the unit, the psychiatrist did not initiate psychotropic medications during the inpatient stay and provided a diagnosis of Depressive Disorder Not-Otherwise-Specified (and indicated that Thomas did not meet criteria for a current Major Depressive Episode). The psychiatrist also indicated a rule out for Personality Disorder Not-Otherwise-Specified. At his first appointment at the outpatient clinic, the social worker completing the intake referred him for IPT, which was conducted with the first author. Thomas agreed to an evaluation for the suitability of IPT and agreed to the time-limited nature of the treatment.

The DSM-IV diagnoses most appropriate to Thomas’ presentation at the start of outpatient therapy were Depressive Disorder Not-Otherwise-Specified (with criteria met for Minor Depression) and Anxiety Disorder Not-Otherwise-Specified (with some criteria met for Generalized Anxiety Disorder). Regarding standardized assessment measures, at the first evaluation session, the IPT therapist administered the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) and GAD-7 (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lowe, 2006); Thomas’ score on the PHQ-9 was a two, and he endorsed depressed mood and feeling bad about himself over the previous two weeks. The therapist also had Thomas retrospectively rate his depressive symptoms at their worst point immediately preceding the psychiatric hospitalization; Thomas scored a 7, and endorsed sad mood and feeling bad about himself more than half the days and the belief that he would be better off dead, low energy, and trouble sleeping for several days. The therapist hypothesized that these scores underestimated Thomas’ degree of depression severity but decided not to spend session time addressing this issue given that Thomas’ suicide risk, rather than depressive symptoms per se, was to be the focus of treatment. Further, the therapist hypothesized that the emphasis in IPT on eliciting affect and fostering an understanding of one’s emotions would likely target this issue. Similar to his score on the PHQ-9, Thomas’ score on the GAD-7 at intake was a 5; the therapist again hypothesized that this score underestimated Thomas’ degree of anxiety symptomatology. The therapist did not spend session time completing a more thorough diagnostic assessment regarding the patient’s mood symptoms, as it was clear to the therapist that the patient had a history of a prior Major Depressive Episode and an additional episode (either major or minor) precipitating the patient’s psychiatric hospitalization. Further, the therapist did not believe that clarifying major/minor would significantly improve case conceptualization or treatment outcomes. At the beginning of treatment, Thomas was quite anxious and lonely and thus quite talkative and often difficult to redirect. Thus, the therapist stopped diagnostic assessment when she had ascertained that Thomas had a history significant for severe depression and that the most recent episode was largely resolved, as this was the information needed to inform suicide risk assessment – and suicide risk was the focus of treatment. Further, the therapist did not complete an in-depth assessment of personality disorder features given the time-limited nature of treatment and her assessment in the evaluation sessions that indicated Thomas was capable of effectively engaging during therapy sessions.

Presenting complaints

The IPT therapist gathered information about Thomas’ presenting complaints, psychiatric symptoms, and psychosocial history in two evaluation sessions. Thomas described his reason for seeking therapy as the presence of overwhelming stress in his life. He described conflicts between himself and his adult sons in the month prior to the psychiatric inpatient stay; he found the disputes devastating because of his intense desire for a close-knit family. He also stated that both of his parents died in the previous year, and that the stress with his sons had kept him from grieving the loss of his parents. He indicated the presence of depressed mood beginning after the death of his mother, as well as difficulty falling asleep, mild decrease in energy, and decreased appetite, all of which improved during inpatient hospitalization. Thomas noted that two weeks prior to the ED visit, his sons stopped speaking to each other – a stressor that Thomas described as the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Thomas’ discussion of his mental health symptoms in an interpersonal context indicated that he would likely accept an IPT approach to address his on-going suicide risk and distress. At the end of the IPT evaluation, the therapist shared with Thomas that the Grief and Interpersonal Disputes modules of IPT would likely be good matches to target the stressors Thomas believed contributed to his depression – namely, the loss of his parents and the disputes with his sons. Thomas agreed with this initial formulation as well as the goal of preventing a future suicidal crisis and contracted with the therapist for a 16-session course of IPT.

History

Thomas was an only child who grew up on his parents’ small farm. He recalled living far away from other children and that he spent most of his childhood with his parents and their friends or playing by himself. He reported great pride in his career as a state trooper and ongoing involvement in a state trooper association after his retirement 15 years prior. He divorced after 20 years of marriage shortly after he retired. Thomas stated that the reason for the divorce was the couple’s decision to move to a southern state after his retirement – a decision that his wife was happy about and he was not. Thomas reported that he was treated for depression with fluoxetine after the move south. Thomas stated that the move drove them apart, and eventually, he moved back north and the couple divorced. He described their ongoing relationship as amicable and respectful, noting that they spoke regularly about their concerns regarding one of their sons who had a chronic medical illness.

Assessment

In the second evaluation session, Thomas completed the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire, a self-report instrument designed to measure the key constructs of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010)—thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Thomas endorsed feeling “disconnected from others” and “lonely” as “somewhat true for me” on the scale. When the therapist asked Thomas to think back to how he was thinking and feeling the day he went to the hospital, Thomas endorsed two items assessing perceived burdensomeness as “very true for me” — “the people in my life would be better off if I were gone” and “I make things worse for the people in my life.” Thomas stated that his duty as a father was to keep a tight knit family and that when his sons stopped speaking he felt like they would be better off without him.

Another key assessment area within the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide is the degree to which an individual may possess the acquired capability for suicide. Given Thomas’ familiarity with and fondness for guns, as well as the presence of several guns with ammunition in his home, the therapist hypothesized that Thomas had an elevated level of acquired capability, which therefore would need to be addressed clinically. The therapist did so by providing psychoeducation about suicide risk and working with Thomas to remove the guns from the home. Regarding psychoeducation, the therapist first taught Thomas about the constructs of the theory and provided feedback on her conceptualization of his level of suicide risk.

Even though Thomas did not present with indications of cognitive impairment on a screening instrument (i.e., score greater than 26 on the SLUMS Examination; Tariq, Tumosa, Chibnall, Perry, & Morley, 2004), the therapist was mindful of the utility of presenting information in digestible pieces for all clients and the fact that these pieces may need to be smaller for older adults. The therapist, therefore, frequently checked-in with Thomas about his understanding of the material. The therapist first shared with Thomas her understanding of what precipitated the referral for therapy and elicited Thomas’ feedback about that information: “Thomas, you were referred to the clinic because you were having thoughts about killing yourself. Specifically, you were thinking about shooting yourself with a gun. Is that right?” [Thomas nods]. “I think that addressing the stress in your life that lead to these suicidal thoughts is an important treatment goal. What do you think about that?” Thomas responded that his stress was ongoing, though less severe, and that he wasn’t sure how to manage it. He then began describing a recent conflict with his son. The therapist gently re-directed Thomas, stating, “The conflict with your son is a source of huge stress right now. It will be important for us to talk more about that. Right now, I want to keep us on the topic of your suicidal thoughts. Is it okay, if we get off track, if I remind you of this?” Thomas agreed that he had difficulty focusing and that redirection would be fine.

Next, the therapist shared information about how she assessed Thomas’ suicide risk and how his risk changed from when he presented at the ED to his current presentation: “Thomas, I want to share with you how I am thinking about your risk for suicide. Also, we can discuss things we can do to lower your risk. When you were admitted to the hospital, your risk was severe. This is because you had a plan for how to kill yourself, but you didn’t have a solid plan for keeping yourself safe. Does that sound right? Did I miss anything?” Thomas responds, “that sounds right, I just wanted to end it all.” The therapist nods and continues. “Right now, I think your risk is moderate. Why do you think your risk is lower now?” Thomas responds, “My stress is a lot lower. The hospital and the doctors helped a lot. I feel better.” The therapist affirmed Thomas’ rationale and added that in their earlier assessment, he reported an absence of suicidal thoughts for over one week. The therapist also noted Thomas’ commitment to give his guns to his roommate, his commitment to therapy, and his commitment to using the safety plan developed in the hospital.

Next, the therapist reviewed the risk factors Thomas presented with, taking special care to highlight the interpersonal nature of the stressors. “Thomas you told me about some of the things that led to you feeling stressed and overwhelmed. It has a lot to do with how things were going with the people in your life. You were feeling lonely and isolated. You thought a lot about the deaths of your parents. You also thought a lot about the arguments with your girlfriend. Is that right?” Thomas nodded and provided an example. The therapist also discussed with Thomas the concept of acquired capability, framing “knowing how to use guns” as something that might make Thomas “less scared” of using a gun for suicide. She reinforced the need for means restriction.

Finally, the therapist discussed with Thomas actions to take to manage his level of risk, including a phone check-in later in the week, reviewing his safety plan, discussing emergency numbers, and obtaining consent for the therapist to speak with Thomas’ primary care physician. Thomas agreed with the therapist’s risk formulation and suggestions for safety planning, except for the need to address gun ownership. This complicating factor is discussed below.

An essential assessment strategy in IPT is completion of the Interpersonal Inventory at the beginning of treatment. Engaging in this exercise involves briefly describing the key people in the patient’s life in the here and now, with a focus on what the relationships mean to the patient and any problems or strengths the patient believes characterize the relationships. Brief mention can also be made of key people in patient’s past. In describing how to complete the inventory with older adults who have a lifetime of relationships and may be talkative and eager to share stories about the people in their lives, Hinrichsen and Clougherty (2006) recommend introducing the inventory in the following way, with an explicit time limit: “I’d like to get a general sense of the important people in your life. At this point, we won’t go into detail about those relationships, but talk for about 5 or 10 minutes about each person you feel is important to you” (p. 79).

The Interpersonal Inventory was completed with Thomas in the first two sessions. Thomas had no problem identifying six key people in his life, which might suggest a high level of belongingness. However, as the therapist and Thomas discussed these people, it became apparent that Thomas felt very lonely. Of note, even though Thomas was given instructions to describe the key people in his life right now, he listed his mother and father. The extent to which these losses were affecting Thomas became increasingly clear to the therapist. Thomas also listed his three adult sons, yet also reported experiencing on-going conflict with all of them. The final person Thomas listed was his ex-fiancée, with whom he reported satisfying sexual relations, but on-going conflict. Friends were noticeably absent in the inventory. When the therapist shared this observation with Thomas, he reported never having any close friendships that were not also romantic in nature. At this point, Thomas did not perceive this to be a problem and did not desire friendships.

The IPT therapist slightly modified the process of completing the Interpersonal Inventory in order to gain information about the interpersonal context of Thomas’ suicide ideation. In other words, were there key people in his life who functioned as social supports or buffers against suicide risk and were there key people with whom he experienced conflict that functioned to increase his suicide risk? She referred back to the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire and asked Thomas to think back to how he was feeling in the days leading up to the hospitalization—specifically feelings of loneliness and the belief that others would be better off if he were gone. The therapist then reviewed the names on his inventory and asked Thomas to indicate if conflict with his sons or others not on this list, including his ex-fiancée and his former roommate, were on his mind at that time; she also asked who in his life he felt disconnected from during that time, including his ex-fiancée and former roommate. Thomas indicated that in the days leading up to his hospitalization, he could not stop thinking about his sons and how he failed them and they would be better off without him. Thus, in the case conceptualization below, the therapist emphasized Thomas’ relationship with his sons as these relationships appeared most functionally related to Thomas’ suicide risk. Although the therapist perceived Thomas’ relationships with both his ex-fiancée and former roommate (a woman he had romantic feelings for) to be problematic, they did not appear to be functionally connected to Thomas’ suicide risk, and thus, in the context of a time-limited course of IPT, the therapist chose not to focus on these relationships.

Case Conceptualization

Through the completion of the Interpersonal Inventory and assessment of the patient’s psychiatric and psychosocial history, the therapist hypothesized that the loss of Thomas’ parents, in close proximity to the stress with his sons, prevented the natural grieving process, resulting in Complicated Grief. This syndrome, although not included in the DSM-IV, has been shown to be a reliable presentation of symptoms that occurs in 10–20% of bereaved individuals (Prigerson et al., 1999). Complicated Grief has also been linked to elevated risk for suicide, including high rates of a wish to die and suicide attempts (Szanto et al., 2006). The therapist presented a case conceptualization to Thomas that included working through two IPT problem areas—Grief and Interpersonal Disputes (the combination of losses and family conflict were hypothesized by the therapist to have led to complicated grief)—in order to target and prevent a future suicidal crisis.

Specifically, in the third session, the therapist shared her conceptualization with Thomas. She began by stating she would like to give Thomas some feedback: “You had a lot of stress in your life in the months before you went to the hospital, including the death of both of your parents and disputes with your sons. I can tell that one of your most deeply held values is family and that your family is your most important source of social support.” Thomas nodded and affirmed that his family is “everything.” The therapist continued “After your parents died, you lost a huge source of support, but you had to focus on coping with the disputes with your sons that left you without the emotional resources to grieve the deaths of your parents. [Therapist asked Thomas to share his understanding so far]. Then, the arguments between your sons escalated and they stopped talking. This was the straw that broke the camel’s back, as you said. It felt like your whole family was falling apart and you were to blame. Did I get that right?” [Thomas affirmed and provided an example]. “Right, you were thinking, ‘I’m a terrible father, I’m a burden on my sons. You began thinking about killing yourself with your pistol, including having images in your head of getting the gun out, loading it, and pulling the trigger.” The therapist again asked for feedback and then provided psychoeducation on suicide risk grounded in the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide: “You’re not alone in having these types of thoughts. In fact, we know that when people feel lonely and like a burden on others, they are more likely to have thoughts of killing themselves. Therapy should help you understand the problems that caused you to feel lonely and like a burden that in turn lead to suicidal thoughts. I said a lot just now, what did you hear from me?” [Thomas responds]. The therapist continues, “Yes, and therapy should help you get more connected with people and feel less lonely. It should help you resolve disputes with others, and potentially change your expectations about yourself and others that led you to feel like a burden. Do these seem like good areas for us to focus on?”

Thomas agreed that the disputes with his sons were key causes of his thoughts about suicide. The therapist gently inquired about the other aspect of the formulation (i.e., the grief component), asking whom he had talked to when his parents died. He stated that he had never talked to anyone about his parents’ death. Suddenly, he began sobbing, with his face in his hands, stating, “I just miss them so much.” The therapist responded by normalizing and validating Thomas’ grief response, keeping in mind that he might feel that his emotional response was shameful or embarrassing. Thomas responded by stating, “I shouldn’t be crying. I try not to cry.” The therapist handed him a tissue and said, “It takes courage to feel these difficult emotions, Thomas. I’m honored that you could share this with me.” At this point, Thomas continued to cry, but made eye contact with the therapist and appeared to reconnect. This interaction was a sign to the therapist that grief would likely be a useful problem area for Thomas, given the presence of a “stuck point” and significant associated affect. However, at this point the therapist decided to finish the task of the session, which was to review the formulation and agree on treatment goals.

Course of Treatment and Assessment of Progress

In the fourth and fifth sessions, the therapist spent time assessing Thomas’ suicide risk in more detail and discussing problems that arose during the week through the lens of the case conceptualization in order to refine the conceptualization and better understand how to reduce Thomas’ suicide risk. In these initial sessions, IPT problem-solving techniques were used to help Thomas cope with interpersonal stressors in his life without using suicide as an escape. Specifically, Mother’s Day was coming up in the week following the fifth session and Thomas was worried about how he would feel on Mother’s Day. Thomas and his therapist formulated the problem as “I may feel lonely on Mother’s Day.” Thomas stated his goal was to “leave the house and do something nice on Mother’s Day.” Thomas generated several solutions and described their pros and cons. He eventually chose to go for a walk by the river and visit a favorite store. The next session, he reported doing both activities and feeling okay on Mother’s Day with no thoughts of suicide. The remainder of this session was spent exploring Thomas’ grief reactions to the loss of his parents. The therapist and Thomas reviewed his experiences of losing his parents in some detail, including what it was like to be in the hospital room with his mother when she died. Thomas brought in the eulogies he wrote for his parents and shared these with his therapist. The therapist helped Thomas identify ‘stuck points’ in his grief response, such as Thomas’ lack of memory for when he had to tell his mother that his father had died. During these sessions, Thomas cried openly and the therapist facilitated the expression and labeling of Thomas’ emotions.

During the seventh session, the discussion was turned to how and why Thomas had been unable to grieve the loss of his parents on his own, which came up when Thomas changed the subject from the loss of his parents to on-going problems with conflict between his sons. Changing the subject was a behavior that had occurred in nearly every session; at this point, the therapist believed she had sufficient rapport and alliance, and pointed out the behavior to Thomas. Doing so allowed Thomas and his therapist to complete an Interpersonal Incident Analysis to better understand the function of his behaviors. In IPT, the incident analysis involves a functional analysis of an interpersonal situation, and is grounded in the assumption of attachment theory that behavior is problematic (and leads to symptoms) when it thwarts interpersonal needs, and adaptive when it facilitates meeting interpersonal needs. Through this process, Thomas was able to identify that he would bring up problems with his sons in sessions after discussing feelings of loneliness: “If I’m worrying about Josh, I’m not thinking about being lonely.” The therapist asked Thomas if he used this strategy of distracting himself from his feelings outside of the sessions and a discussion ensued in which Thomas and his therapist identified that Thomas fixated on the stressors among his sons after the loss of his parents, and thereby thwarted the grieving process. Thomas was also able to identify that this strategy of avoiding his feelings did not work: “It’s a Band-Aid and the loneliness ends up getting bigger.” With his therapist’s help, Thomas was able to state that keeping his feelings of loneliness inside or ignoring them, was not a viable long-term solution to the problem of loneliness. The discussion focused on the concept of a need to belong and how loneliness is a cue that our belongingness needs are not being met.

The next two sessions were spent completing Interpersonal Incident Analyses about the events that directly led up to Thomas’ hospitalization. By going through the events in detail and eliciting affect, the therapist was able to help Thomas identify that his feelings of being a burden substantially increased his feelings of agitation and anxiety, which precipitated thoughts of using his pistol to shoot himself. Specifically, the therapist elicited the following insight from Thomas when she reflected that he seemed to hold high expectations of himself as a father and that it was scary to lose his parents as role models: “I couldn’t control my mother and father’s deaths, but I should be able to keep a tight-knit family.” Thomas was able to realize that his expectations about controlling his sons’ behaviors made it harder for him to act calmly and effectively with them. He engaged with the therapist in problem solving to more effectively communicate with his sons, and also to challenge his thoughts that being unable to solve his sons’ problems made him a burden or less of a father.

The final sessions were spent helping Thomas explore whom in his life he could talk to when he felt lonely or stressed about his family. Thomas resisted the idea of talking to friends because he shared that he had never really had friends and was unsure how to be in relationships that weren’t romantic or familial. The goal in exploring these ideas with Thomas was to help him accept that increasing social support in his life could be an on-going treatment goal, given that he would be continuing in treatment with another therapist. Through expressing sadness that he never had brothers or sisters, Thomas was able to begin to accept that friendships might be helpful for him. He agreed to join a Behavioral Activation psychotherapy group at the clinic and to use the group to increase social activities in his life.

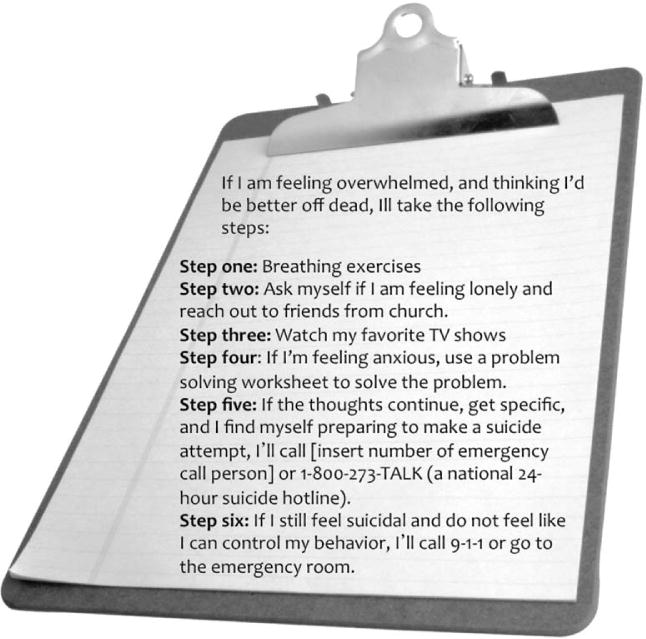

An additional therapeutic task near the end of treatment involved updating Thomas’ safety plan. The therapist asked Thomas what he would like to put on his safety plan given what he learned in therapy. Thomas generated four things he could do if he started to feel overwhelmed and began thinking he would be better off dead. First, he wanted to list “breathing exercises” that he had learned while in the hospital. Second, Thomas stated, “If I’m lonely, I should reach out,” thus demonstrating a high degree of insight into the role low belongingness played in his suicidal crisis. After praising Thomas for generating this item, the therapist helped Thomas expand the coping strategy by listing specific people. Third, Thomas stated he could watch his favorite TV shows. Finally, Thomas stated, “if I’m worrying, I can use one of those problem solving worksheets you gave me.” Again, the therapist praised Thomas for how much he had learned in therapy. Finally, the therapist helped Thomas add emergency numbers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Coping Card

Complicating Factors

Throughout the course of treatment, Thomas would bring up stressors in his life unrelated to the current, agreed upon problem area. For example, during a session for which it was planned to discuss Thomas’ mother’s death, Thomas began the session telling his therapist about his youngest son and concerns about his son’s health. In this case, and every other, the therapist validated Thomas’ feelings and then re-directed him to the problem area agreed upon in IPT (i.e., Grief or Interpersonal Disputes).

Thomas’ pride in his identity as a state trooper led him to resist relinquishing his guns. Thus, he had access to lethal means in his home when his roommate moved out several sessions into the course of IPT. With the development of therapeutic rapport and alliance, and the shared conceptualization of Thomas’ problems, Thomas was able to agree that he would give the key to where he stored his guns to a friend if he were to develop suicidal thoughts, and that he would share this information with his treatment providers. This solution made sense to Thomas in the context of his therapist’s description of acquired capability for suicide and how this capability increases risk in the context of desire for suicide. Although the therapist would have preferred that Thomas sell or give away his guns, Thomas was not willing to do this. The therapist consulted with the director and medical director of the clinic; together, they considered options such as mandating that Thomas remove the guns in order to receive treatment at the clinic. After discussion and weighing pros and cons, the group agreed that if the therapist was comfortable treating Thomas in this arrangement and believed he would follow through on his commitment, then this arrangement was acceptable, although not ideal.

Presentation at the end of IPT

The IPT therapist completed the PHQ-9 at the final session and Thomas scored a zero, indicating the absence of death and suicide ideation for the prior two weeks, as well as euthymic mood. Thomas reported hopefulness about the future and was able to verbalize what he learned in therapy, including that seeking social support and talking about feelings is important and that when his sons experience difficulties, this does not mean that he is a bad father and that they would be better off if he were gone. Thus, Thomas demonstrated insight into his need for “belongingness” as well as insight regarding his cognitive distortion that his family would be better off without him (i.e., burdensomeness). Thomas was also able to state from memory the steps on his coping card and reported willingness to continue in supportive individual therapy and group therapy to maintain his gains. From the framework of the Interpersonal Theory, these factors are supportive of the patient’s readiness for termination. Given his history of gun use and relative fearlessness about using guns, the therapist rated his suicide risk at the end of treatment as low-to-moderate (rather than low) and encouraged the transfer providers to regularly assess his suicide risk. His presentation at the end of IPT suggested that he would be less likely to experience a suicidal crisis in the future, given increased insight into how his interpersonal relationships contribute to suicide risk, but, of course, this cannot be known definitively.

Follow-up

In the period between the end of IPT and the start of the Behavioral Activation group, Thomas experienced significant stress—concerns about his youngest son and mental health problems. Thomas successfully completed the Behavioral Activation group and was an active participant throughout. He worked on the goals of increasing his social interactions and continued in supportive psychotherapy with a social worker in his clinic. He remained without suicidal thoughts two months after treatment and also reported a stable, euthymic mood.

Treatment Implications

This case illustrates how targeting the constructs of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness with Interpersonal Psychotherapy may help older adults resolve suicide ideation and prevent recurrences of suicidal crises. Thomas’ loneliness was conceptualized as an indicator that his need to belong was not being met. The therapist hypothesized that Thomas’ unresolved grief was contributing to his feelings of loneliness, thus the IPT grief problem focus was used to help Thomas process his emotions and share his emotions with others, including individuals from his trooper association and his church. By the end of treatment Thomas was able to verbalize that he could see value in sharing his feelings with others because talking with his therapist was helpful, but had not yet taken the first step in doing so. His therapist encouraged him to use the Behavioral Activation group to help him become more engaged with individuals in his church and trooper association.

Thomas’ statements that he was “no good” to his family, and that he believed his sons would be better off if he were dead, indicated that perceiving himself to be a burden on his family was a trigger for suicidal thoughts. The therapist addressed these perceptions through the Interpersonal Disputes problem focus of IPT. Thomas’ unrealistic expectations of himself as a father, as well as his unrealistic expectations of his sons (i.e., they “should” be more grateful for having siblings when Thomas had no siblings), were addressed through analyses of his interactions with his sons, followed by problem-solving regarding improving future interactions.

Recommendations to Clinicians and Students

The positive outcome in this case suggests that using the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide to inform the selection of relevant modules in IPT may be useful for clinicians working with older adults at risk for suicide. More rigorous empirical data, in the form of empirical case studies or clinical trials, are needed to confirm these hypotheses. However, given the lack of data to drive treatment decisions with suicidal older adults at present, this case study provides a theoretically and empirically informed approach to psychotherapy with older adults at elevated suicide risk. IPT guides therapists to look for one of four interpersonal stressors that may be present in a client’s life – grief, role transitions, interpersonal disputes, and interpersonal sensitivity (i.e., skills deficits). The Interpersonal Theory provides a rationale for choosing one problem focus over another, and illuminates the mediating psychological processes that may account for why these stressors are related to suicide risk. For example, in the absence of theory, it is not clear why Thomas’ disputes with his sons would be functionally related to suicide risk. However, the knowledge that Thomas felt like a burden on his sons when these disputes escalated, combined with empirical data demonstrating an association between perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation, attempts, and deaths (Van Orden et al., 2010), guided the therapist to target these disputes. Doing so is beneficial therapeutically to the extent that it reduces (or prevents the recurrence of) Thomas’ belief that he is a burden on others.

Thus, the Interpersonal Theory can provide guidance on which problem focus to select, as well as what conditions must be satisfied for an individual to have successfully completed treatment with regards to reducing suicide risk. In short, we recommend the following as treatment goals for clinicians wishing to utilize this approach. First, a client should be guided therapeutically to identify and confront his or her feelings of being a burden, should understand why he/she felt that way, and be able to reconsider to perceptions of burdensomeness should they arise in the future. Second, a client should have sufficient sources of social support so that his/her need to belong is met outside the therapeutic relationship. Any significant obstacles to belongingness should be explored and problem solving conducted to remove them. The client should understand what led to his/her suicidal crisis and how to use skills learned in therapy to combat thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness should they arise in the future. Further, clients should understand the concept of acquired capability and that a safety plan should be in place to restrict access to lethal means in times of stress.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Van Orden received grant support from a National Institute of Mental Health T32 National Research Service Award training grant (2T32MH020061-11; PI: Conwell).

Footnotes

Details about the patient have been changed for privacy reasons. The patient provided consent for the publication of this manuscript.

References

- Alexopoulos GS, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Bruce ML, Katz IR, Raue PJ, Mulsant BH, Ten Have T. Reducing suicidal ideation and depression in older primary care patients: 24-month outcomes of the PROSPECT study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):882–890. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121779. doi: appi.ajp.2009.08121779 [pii]10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08121779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SS, Leung VP, Tsoh J, Li SW, Yu CS, Yu GK, Chiu HF. Outcomes of a two-tiered multifaceted elderly suicide prevention program in a Hong Kong chinese community. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(2):185–196. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181e56d0f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comtois KA, Linehan MM. Psychosocial treatments of suicidal behaviors: A practice friendly review. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;62(2):161–170. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Rotenberg M, Caine ED. Completed suicide at age 50 and over. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 1990;38(6):640–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb01422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D, Carollo G, Dello Buono M. Lower suicide rates associated with a Tele-Help/Tele-Check service for the elderly at home. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152(4):632–634. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D, Dello Buono M, Dwyer J. Suicide among the elderly: the long-term impact of a telephone support and assessment intervention in northern Italy. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;181:226–229. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(21):2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heisel MJ, Duberstein P, Talbot NL, King DK, Tu X. Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for older adults at risk for suicide: Preliminary findings. Professional Psychology – Research & Practice. 2009;40(2):156–164. doi: 10.1037/a0014731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron MP, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Jiaquan X, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final Data for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2009;57(14):1–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichsen GA, Clougherty KF. Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed older adults. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Rudd MD. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide: Guidance for Working with Suicidal Clients. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. doi: jgi01114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Dew MA, Mazumdar S, Begley AE, Cornes C, Miller MD, Reynolds CF., 3rd Combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy as maintenance treatment for late-life depression: effects on social adjustment. The American journal of psychiatry. 2002;159(3):466–468. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TR, Cheavens JS, Cukrowicz KC, Thorp SR, Bronner L, Beyer J. Treatment of older adults with co-morbid personality disorder and depression: A dialectical behavior therapy approach. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22(2):131–143. doi: 10.1002/gps.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JL, Santos JF. Methods of suicide by age: Sex and race differences among the young and old. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 1985;22(2):123–139. doi: 10.2190/tx1p-5pxc-k4g5-1vug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD. Clinician’s guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy in late life. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oyama H, Sakashita T, Ono Y, Goto M, Fujita M, Koida J. Effect of community-based intervention using depression screening on elderly suicide risk: a meta-analysis of the evidence from Japan. Community Mental Health Journal. 2008;44(5):311–320. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Shear MK, Jacobs SC, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Maciejewski PK, Davidson JR, Zisook S. Consensus criteria for traumatic grief. A preliminary empirical test. The British journal of Psychiatry. 1999;174:67–73. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CF, 3rd, Miller MD, Pasternak RE, Frank E, Perel JM, Cornes C, Kupfer DJ. Treatment of bereavement-related major depressive episodes in later life: a controlled study of acute and continuation treatment with nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy. The American journal of psychiatry. 1999;156(2):202–208. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. doi: 166/10/1092 [pii] 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry HM, Morley JE. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination is more sensitive than mini-mental state examination (MMSE) for detecting mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900–910. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision. New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Tang L, Oishi S, Katon W, Williams JW, Jr, Hunkeler E, Langston C. Reducing suicidal ideation in depressed older primary care patients. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2006;54(10):1550–1556. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00882.x. doi: JGS882 [pii] 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117(2):575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Distribution of suicides rates (per 100,000), by gender and age, 2000. 2002 Retrieved April 19, 2010, from http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicide_rates_chart/en/index.html.