Abstract

Objective

To determine the location of Canadian abortion services relative to where reproductive-age women reside, and the characteristics of abortion facilities and providers.

Design

An international survey was adapted for Canadian relevance. Public sources and professional networks were used to identify facilities. The bilingual survey was distributed by mail and e-mail from July to November 2013.

Setting

Canada.

Participants

A total of 94 abortion facilities were identified.

Main outcome measures

The number and location of services were compared with the distribution of reproductive-age women by location of residence.

Results

We identified 94 Canadian facilities providing abortion in 2012, with 48.9% in Quebec. The response rate was 83.0% (78 of 94). Facilities in every jurisdiction with services responded. In Quebec and British Columbia abortion services are nearly equally present in large urban centres and rural locations throughout the provinces; in other Canadian provinces services are chiefly located in large urban areas. No abortion services were identified in Prince Edward Island. Respondents reported provision of 75 650 abortions in 2012 (including 4.0% by medical abortion). Canadian facilities reported minimal or no harassment, in stark contrast to American facilities that responded to the same survey.

Conclusion

Access to abortion services varies by region across Canada. Services are not equitably distributed in relation to the regions where reproductive-age women reside. British Columbia and Quebec have demonstrated effective strategies to address disparities. Health policy and service improvements have the potential to address current abortion access inequity in Canada. These measures include improved access to mifepristone for medical abortion; provincial policies to support abortion services; routine abortion training within family medicine residency programs; and increasing the scope of practice for nurses and midwives to include abortion provision.

Résumé

Objectif

Vérifier où sont situés les services canadiens d’avortement par rapport aux endroits où habitent les femmes en âge d’enfanter et déterminer les caractéristiques des établissements et des médecins qui offrent des avortements.

Type d’étude

On a adapté une enquête internationale pour tenir compte du contexte canadien. On s’est servi de données publiques et de réseaux professionnels pour identifier les établissements. Le questionnaire a été distribué dans les deux langues par voie postale et par courriel, de juillet à novembre 2013.

Contexte

Le Canada.

Participants

Un total de 94 cliniques d’avortement.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Le nombre et les lieux des services d’avortement ont été comparés à la répartition des femmes en âge de procréer, selon le lieu de résidence.

Résultats

On a répertorié 94 établissements canadiens qui offraient des avortements en 2012, dont 48,9 % au Québec. Le taux de réponse était de 83,0 % (78 sur 94). On a reçu des réponses de chacune des régions administratives où ces services existaient. Au Québec et en Colombie-Britannique, les services d’avortement sont répartis à peu près également entre les grands centres urbains et les régions rurales; dans les autres provinces canadiennes, les services sont principalement dans les grands centres urbains. Aucun service de cette nature n’a été trouvé à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard. Les répondants on dit avoir fait 75 650 avortements en 2012, dont 4,0 % d’avortements médicaux. Les établissements consultés sont rarement victimes de menaces ou de violence, ce qui contraste fortement avec les établissements américains qui avaient répondu à la même enquête.

Conclusion

Au Canada, l’accès aux services d’avortement varie beaucoup selon les régions. La distribution régionale de ces services ne tient pas compte des endroits où résident des femmes en âge de procréer. Le Québec et la Colombie-Britannique ont adopté des stratégies efficaces pour tenir compte de ces disparités. Avec des politiques appropriées et de meilleurs services, on pourrait éventuellement corriger ces inégalités au Canada. Les mesures pourraient comprendre un meilleur accès au mifépristone pour l’avortement médical; des politiques provinciales pour appuyer les services d’avortement; l’inclusion obligatoire de programmes de formation sur l’avortement durant la résidence en médecine familiale; et un élargissement du champ de pratique des infirmières et des sages-femmes pour leur permettre de faire des avortements.

Abortion is a common reproductive care procedure, experienced by 31% of Canadian women during their lifespan.1 Rural compared with urban distribution of abortion services, and the relationship to both the distribution of women and to federal and provincial health policies, has not been documented in Canada.

Federal legislation includes a requirement for each provincial and territorial health system to provide abortion services.2 Each of the 13 provinces and territories determines both health policy and health services for their own jurisdiction.3 Despite the legislation, abortion service availability is thought to vary within and among Canadian health systems.4,5 It has been clearly documented that at least 2 provinces have failed to meet these requirements.6,7 In Ontario, disparities exist between rural and urban access, which might be mirrored in other jurisdictions.8–10 National evaluation of abortion health services and their distribution has been limited by incomplete data collection from nonhospital facilities, where most abortions are provided.11–13

An instrument assessing abortion health services has been used in the United States (US) since 1997 for iterative evaluation14–17 and to provide best-practice evidence supporting 2 textbooks.18,19 Norman et al used this instrument to survey abortion provider practices in British Columbia (BC) in 2010.20,21

In 2013 this instrument was used to survey facilities and providers about 2012 abortion services, techniques, and experiences in the US and Canada. In this article we present Canadian findings from this study related to abortion health services distribution, delivery, and providers, as well as facility characteristics and experiences of harassment. Techniques of first-trimester medical abortion across Canada are detailed in the companion paper in this issue (page e201).22

METHODS

We distributed a national cross-sectional self-administered survey to facilities providing abortion services in all regions of Canada. We used public sources, including Internet-based abortion facility listings, advertisements, online directories, and professional networks, to identify abortion facilities in all Canadian jurisdictions. We defined a facility as any service or group of services offering abortions, including hospitals, community health centres, clinics, and physician offices. All identified facilities were contacted 1 month before distribution of the survey by mail, e-mail, or telephone to confirm current service provision and to notify them of the pending invitation to participate in the survey.

We adapted the previously published US instrument to be relevant to the Canadian context.14–16 To modify the survey for Canadian use, lists of medications approved for use were updated; health professional credentials approved for provision of abortion services were added; and US-specific questions related to payment for services were removed. All Canadian context changes were reviewed by 5 abortion care experts for face validity and relevance. Three types of question booklets were distributed to each facility. Each facility was provided booklets for completion by the administrator (29 questions on the overall facility services and experiences); up to 5 surgical abortion providers (97 questions on surgical abortion techniques); and up to 5 medical abortion providers (33 questions on medical abortion techniques).

The final version of the survey was professionally translated into French, with review by 3 Francophone abortion experts. Surveys were available in both English and French, in print and in Internet-accessible format, and were distributed by mail and by e-mail. We mailed a small honorarium in the form of a coffee card to each facility administrator in recognition of the time taken to distribute, collate, and return responses from their facilities. Dillman technique23 reminders were sent at 1 and 2 weeks and again for nonresponders at 4 and 6 weeks. Surveys were distributed between July and November 2013. Double data entry was used for all written submissions. Ethics approval was provided by the University of British Columbia and Children’s and Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia Research Ethics Board; ethics approval for the overall international project was provided by the Human Research Protections Program Integrated Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York.

Outcome measures

We were able to identify 94 facilities providing abortion services in Canada. We reported the number and location of services, and compared this information with the distribution of reproductive-age women by location of residence. To illustrate the relationship of abortion service location with the location of women, we used the following definitions. We defined urban facilities as those located within a census metropolitan area (CMA).24,25 All other facilities were defined as rural. We defined reproductive-age women residing in a CMA with abortion services as the number of females aged 15 to 44 years residing in a CMA in 2012, according to Statistics Canada,26 for every CMA where we were able to identify an abortion facility. All other 15- to 44-year-old women in the region in 2012 were defined as not residing in a CMA with abortion services. We reported all results by regions (Atlantic provinces, Quebec, Ontario, the Prairies, BC, and the territories) designated to include a minimum of 4 facilities per region to ensure no individual facility or provider could be identified.

We recorded the data provided by each responding facility administrator on the number of abortions provided in 2012 and by medical or surgical method, as well as facility characteristics and experiences. Provider characteristics are derived from the abortion provider survey responses.

RESULTS

Distribution of identified facilities

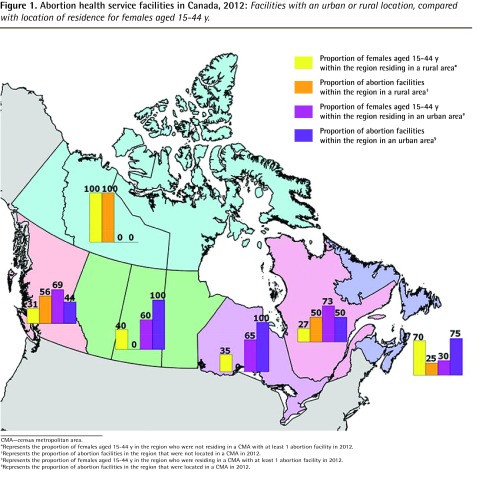

Of the 94 facilities in Canada, 78 (83.0%) responded to our survey, including at least 1 facility in every jurisdiction providing services, and 89.1% (41 of 46) of facilities in Quebec. Nearly half (n = 46, 48.9%) of all identified Canadian facilities are located within Quebec (Table 1)24–26. Figure 1 compares the urban and rural distribution of facilities identified within each region with the reproductive-age females for each region.

Table 1.

Abortion facilities by region and rural area within Canada, 2012

| REGION | TOTAL FACILITIES, N (%) | CANADIAN FEMALES AGED 15–44 Y BY REGION,24–26 % | RURAL FACILITIES (NON-CMA), N (%) | FEMALES AGED 15–44 Y IN THE REGION NOT RESIDING IN A CMA WITH A FACILITY, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 94 (100.0) | 100.0 | 33 (35.1) | 48.0 |

| Atlantic provinces | 4 (4.3) | 6.3 | 1 (25.0) | 70.0 |

| Quebec | 46 (48.9) | 22.3 | 17 (37.0) | 26.9 |

| Ontario | 16 (17.0) | 39.2 | 0 (0.0) | 35.2 |

| Prairies | 8 (8.5) | 18.7 | 0 (0.0) | 40.4 |

| British Columbia | 16 (17.0) | 13.0 | 9 (56.3) | 30.7 |

| Territories* | 4 (4.3) | 0.4 | 4 (100.0) | 100.0 |

CMA—census metropolitan area.

There are no CMAs in any of the 3 territories.

Figure 1.

Abortion health service facilities in Canada, 2012: Facilities with an urban or rural location, compared with location of residence for females aged 15–44 y.

CMA—census metropolitan area.

*Represents the proportion of females aged 15–44 y in the region who were not residing in a CMA with at least 1 abortion facility in 2012.

†Represents the proportion of abortion facilities in the region that were not located in a CMA in 2012.

‡Represents the proportion of females aged 15–44 y in the region who were residing in a CMA with at least 1 abortion facility in 2012.

§Represents the proportion of abortion facilities in the region that were located in a CMA in 2012.

In Quebec and BC, abortion services were nearly equally present in large urban centres (CMAs) and rural locations spread throughout the province. Services in the territories were also located in the largest cities, although no city in the territories is large enough to qualify as a CMA. In Canadian provinces other than Quebec and BC, most identifiable services are located in large urban areas. In Prince Edward Island (PEI), we were unable to identify any facility providing abortion services.

Responding facilities

Among the 78 facilities with either an administrator or a provider respondent, 52 (66.7%) were located in community settings and 37 (47.4%) provided abortion within a hospital, including 11 (14.1%) facilities providing services in both settings (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hospital-affiliated facilities and community settings among abortion facilities with any response, Canada and by region, 2012: N = 78.

| FACILITY | REGION | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| CANADA, N (%) | ATLANTIC PROVINCES, N (%) | QUEBEC, N (%) | ONTARIO, N (%) | PRAIRIES, N (%) | BRITISH COLUMBIA, N (%) | TERRITORIES, N (%) | |

| All responding facilities | 78 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 41 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) |

| Community setting* | 52 (66.7) | 2 (50.0) | 33 (80.5) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (66.7) | 8 (53.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hospital-affiliated facility† | 37 (47.4) | 2 (50.0) | 15 (36.6) | 4 (44.4) | 2 (33.3) | 11 (73.3) | 3 (100.0) |

| Both community setting and hospital-affiliated facility | 11 (14.1) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (17.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) |

Community settings include traditional community health centres, free-standing abortion clinics, and private doctor’s offices offering abortion services.

Hospital-affiliated facilities include both services conducted in operating rooms and services conducted within ambulatory clinic facilities located within the hospital complex.

Among the 78 responding facilities, we received administrator responses from 74, with 4 additional facilities returning medical or surgical abortion provider surveys. Administrator respondents reported providing a total of 75 650 abortions in 2012 (Table 3). Among these, 4.0% were medical abortions (first or second trimester), most of which were provided at a single facility in BC.

Table 3.

Providers and services among responding Canadian abortion facilities, 2012: N = 74.

| PROVIDERS AND SERVICES | REGION | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| CANADA | ATLANTIC PROVINCES | QUEBEC | ONTARIO | PRAIRIES | BRITISH COLUMBIA | TERRITORIES | |

| Procedures, n (%) | |||||||

| • Total abortions provided in 2012 | 75 650 (100.0) | 3493 (100.0) | 24 106 (100.0) | 15 976 (100.0) | 16 639 (100.0) | 14 872 (100.0) | 564 (100.0) |

| • 1st-trimester surgical abortion | 68 154 (90.1) | 3318 (95.0) | 22 319 (92.6) | 14 994 (93.9) | 15 389 (92.5) | 11 608 (78.1) | 526 (93.3) |

| • 2nd-trimester surgical abortion | 4468 (5.9) | 164 (4.7) | 1541 (6.4) | 881 (5.5) | 936 (5.6) | 935 (6.3) | 11 (2.0) |

| • 1st-trimester medical abortion | 2706 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 62 (0.3) | 101 (0.6) | 274 (1.6) | 2242 (15.1) | 27 (4.8) |

| • 2nd-trimester medical abortion | 322 (0.4) | 11 (0.3) | 184 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 40 (0.2) | 87 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Volume of procedures in facility, n (%) | |||||||

| • Low (< 500 per y) | 39 (52.7) | 1 (25.0) | 27 (67.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 7 (50.0) | 3 (100.0) |

| • Medium (500–1999 per y) | 20 (27.0) | 3 (75.0) | 10 (25.0) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| • High (≥ 2000 per y) | 15 (20.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.5) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (50.0) | 5 (35.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Providers*† | |||||||

| • No. of SAPs‡ | 206 | 6 | 122 | 18 | 21 | 32 | 7 |

| • No. of MAPs | 71 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 5 | 17 | 9 |

| • No. of SAPs asked to complete survey | 138 | 6 | 86 | 7 | 15 | 18 | 6 |

| • No. of MAPs asked to complete survey | 52 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 9 |

MAP—medical abortion provider, SAP—surgical abortion provider.

In Canada, only physicians are licensed to provide abortion services. In some instances the same responding physician provided both medical and surgical abortion.

These numbers represent responses by facility administrators and do not include provider numbers for 4 additional facilities where providers returned surveys but administrators did not, or for 6 facilities where the administrator reported no medical abortion physicians, yet 11 medical abortion physicians from those facilities returned responses.

Surgical abortion providers in Quebec and British Columbia occasionally indicated provision at more than 1 reporting facility; thus, the overall totals for these regions might be overestimates.

A low volume of procedures, fewer than 500 per year, was provided by about half of all of reporting administrators (n = 39, 52.7%), including two-thirds (67.5%) of those in Quebec, with only one-fifth (20.3%) of facilities (7.5% in Quebec) providing 2000 or more abortions per year. These higher-volume facilities were largely ambulatory clinics, with only 20.0% (n = 3) in this category providing services in a hospital setting.

Consistent with current health professional regulations in Canada, all abortions were provided by physicians. Responses were received from 178 unique providers, one-tenth (n = 18) of whom provided services at more than 1 responding facility. Two-thirds (69.1%) of abortion providers were female and more than half (59.6%) were family physicians or general practitioners. Providers reported a mean (SD) age of 48.7 (12.0) years (n = 74).

Facilities reported very little harassment (Table 4). No Canadian facility reported a resignation of an abortion provider–physician or any staff member owing to harassment. Only a single facility reported any resignation of an allied health professional staff member, and in this case the facility specified that the one resignation was not owing to violence, fear, or threats. Similarly, two-thirds of reporting facilities (49 of 74, 66.2%) indicated no episodes of harassment or violence in 2012, with a further 28.4% (21 of 74) reporting solely picketing without interference. Among 7 facilities reporting “other” episodes of harassment, half specified only receipt of harassing e-mail.

Table 4.

Violence or harassment during 2012 at Canadian abortion facilities, by region: N = 74.

| TYPE | REGION | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| CANADA (N = 74), N (%) | ATLANTIC PROVINCES (N = 4), N (%) | QUEBEC (N = 40), N (%) | ONTARIO (N = 7), N (%) | PRAIRIES (N = 6), N (%) | BRITISH COLUMBIA (N = 14), N (%) | TERRITORIES (N = 3), N (%) | |

| No violence or harassment | 49 (66.2) | 1 (25.0) | 34 (85.0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (33.3) | 8 (57.1) | 3 (100.0) |

| Picketing without interference | 21 (28.4) | 3 (75.0) | 4 (10.0) | 6 (85.7) | 3 (50.0) | 5 (35.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Picketing with interference | 2 (2.7) | 2 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vandalism | 2 (2.7) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other* | 7 (9.5) | 1 (25.0) | 4 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

Other forms of violence or harassment included threatening e-mails or telephone calls.

DISCUSSION

We report the first detailed data on abortion facilities and providers in Canada, including data on facilities providing 90.4% of the total number of Canadian abortions (83 708) reported to the Canadian Institute for Health Information for 2012.13 Identified abortion facilities were located only in the largest urban centres for most jurisdictions, except in BC and Quebec, with no facility in PEI.

Notably, nearly half of all facilities identified were in Quebec, a province where 22.3% of reproductive-age Canadian women reside. More equitable distribution of services in Quebec is related to provincial development and planning over more than 4 decades.27,28 The government of Quebec issued a series of family planning policies between 1972 and 1977, funding family planning counseling in community health facilities and developing a network of 21 hospital-based public abortion facilities across the province.27,28 In 1996 ministerial guidelines required each region to create plans for access to first- and second-trimester abortion services.29,30 The provincial government provided additional funding in 2001 to ensure access to first-trimester abortions in each of the 18 regions, and distributed access to second-trimester abortion in 3 regions.31 Training, meetings, research, surveys, and an oversight committee on abortion delivery continue to be provided by governmental and para-governmental organizations in Quebec.31

From 1992 to 2004, the government of BC similarly planned to support distributed services through a task force that made specific recommendations in 1994 to ensure access to abortion care.32 Legislation mandating service in designated hospitals in each jurisdiction was enacted in 1996,33 with laws added in 2001 guaranteeing access to services.34 Since 1993, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre in Vancouver has provided provincial leadership in training providers, supporting rural hospital-based abortion services, and integrating a network of care through a provincial toll-free line to connect women with the closest appropriate abortion service.35 Further, they have supported provincial health services improvement conferences (2009, 2011, and 2014), engaging a range of stakeholders.32,36,37 Featuring collaborative workshops, these events highlight best practices, examine gaps and opportunities, support networking of service providers and health system leaders, and have facilitated health system and services improvement.32,36,37

In contrast, 1989 legislation in New Brunswick specifically impaired access to abortion services by limiting abortion provision to hospitals alone, and by requiring that abortion be performed by a non–family physician specialist and only after approval by 2 physicians.38,39 A January 2015 amendment removed the requirements for a specialist and for approval by 2 doctors, but it maintained the restriction to hospitals.40 In contrast, both Canadian Institute for Health Research data13 and this study (Table 2) indicate that most Canadian abortions are performed in clinic settings.

We were unable to locate any abortion service in the province of PEI. The government of PEI passed Resolution 17 in early 1988 resolving “that the Legislative Assembly of P.E.I. oppose the performing of abortions.”41 Prince Edward Island has since guided service delivery with a policy that no induced abortions would be performed in the province. For example, Health PEI, the provincial organization responsible for the operation and delivery of publicly funded health services, has specified that women must travel to another province to receive abortion services.42

Our findings indicate more than half of all abortion providers in Canada are family physicians or general practitioners. Routine training in abortion care is not offered by Canadian family medicine residency programs, except in BC.43,44 Provision of this training has the potential to improve service distribution.45,46 Access to high-quality training, and support for provision of medical abortion in particular, will have even more relevance since the July 2015 approval for mifepristone use in Canada.47

In Canada, all abortion providers are physicians. Our concurrent survey using the same instrument in the US found that approximately half of all medical abortions are provided by nonphysicians.48 The distribution of allied health professions among all providers was 29% nurse practitioners, 14% physician assistants, 6% certified nurse midwives, and 1% other health care professionals. In many jurisdictions the provision of medical and surgical abortion by allied health professionals has been associated with high-quality care and high patient satisfaction.49–53 Task sharing to better use the full scope of practice of allied health professionals has the potential to improve equitable distribution of abortion services within Canada.

Canadian abortion facilities reported rare harassment. In contrast, among American abortion facilities sampled concurrently 83% reported substantial episodes of harassment, and 10% reported staff resignations owing to harassment.54

Limitations

Our sample was limited to abortion facilities that we were able to detect through publicly available sources and professional networks. We might have been unable to detect providers in rural (non-CMA) hospitals and physicians’ offices in some regions, particularly Ontario, that provide abortion services and might be known among the local community without the need for public advertising. Further, our conclusions with respect to service in Ontario are limited by a low response rate of 56.3%. Two Ontario studies have demonstrated urban-rural disparity in abortion rates8–10 despite the intended presence of at least 1 hospital providing abortion in each Local Health Integration Network.10 The strengths of this study include the use of a proven survey instrument and our high overall response rate, allowing us to present the first detailed study of abortion facility services and experiences in Canada.

Conclusion

Equitable access to abortion service varies by region across Canada. Medical abortion is rare, as is harassment of facilities. Provincial government leadership in BC and Quebec has demonstrated effective strategies to address inequity. Regulatory advances that could improve abortion service access include improved access to mifepristone for medical abortion; provincial leadership supporting abortion services through policy and legislation; implementation of routine training in surgical and especially medical abortion within family medicine residency programs; and regulations to broaden the scope of practice for nurses, midwives, and other allied health professionals to include abortion provision. Health policy and service improvements have the potential to address current abortion access inequity in Canada.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Society of Family Planning Research Fund. Supplemental funding from the Clinical and Translational Science Center of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences was used for French translations of the questionnaires. Infrastructure support for Dr Norman and her team throughout this project was provided by the Women’s Health Research Institute at the BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre. Dr Norman is supported as a Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Public Health Agency of Canada Chair in Applied Public Health Research, and as a Scholar of the Michael Smith Foundation of Health Research. Dr Okpaleke was supported through a master’s scholarship from the Contraception Access Research Team— Groupe de recherche sur l’accessibilité à la contraception. The authors thank Kyle Howe for the development of Figure 1 and Dr Weihong Chen for administrative support services throughout this study.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Disparities in provision of abortion services exist across Canada. Successful strategies to improve equity have been implemented in both British Columbia and Quebec.

Identified abortion facilities were located only in the largest urban centres for most jurisdictions, except in British Columbia and Quebec, where they were spread more equitably. No facilities were identified in Prince Edward Island. Nearly half of all facilities identified were in Quebec.

More than half of all abortion providers in Canada are family physicians or general practitioners. Medical abortion is rare, as is harassment of facilities.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Il existe des disparités régionales dans l’accès aux services d’avortement au Canada. En Colombie-Britannique et au Québec, des stratégies efficaces ont été adoptées pour corriger ces inégalités.

Dans la plupart des régions administratives, les services d’avortement répertoriés étaient localisés uniquement dans les grands centres urbains, sauf au Québec et en Colombie-Britannique où ils étaient distribués plus équitablement. On n’a identifié aucun de ces établissements à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard. Près de la moitié étaient au Québec.

Plus de la moitié de ceux qui font des avortements au Canada sont des médecins de famille. Il y a très peu d’avortements médicaux et les cliniques sont rarement l’objet de menaces.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

The survey was developed by Drs Jones, O’Connell White, Paul, and Lichtenberg, and was revised for Canadian relevance by Drs Norman and Guilbert. Canadian data were collected by Drs Norman, Guilbert, and Okpaleke. Analyses were conducted by Drs Norman, Guilbert, Jones, and Hayden. The first draft was prepared by Drs Norman, Guilbert, and Hayden. All authors contributed to revisions and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

Dr O’Connell White received consultant fees from Teva Women’s Health outside of the submitted work. Dr Norman is the lead investigator on an investigator-initiated Canadian Institutes of Health Research–funded randomized controlled trial to which Bayer Canada donated contraceptive devices. Bayer Canada had no influence on the study design, the collection or analysis of data, or on the decision to publish. Neither Dr Norman nor any member of her team has received support from Bayer Canada during the study or preparation of this manuscript. Dr Guilbert has received honoraria from Bayer Canada and Actavis Canada for conferences and participation in advisory boards and from Paladin Labs for personal consultation.

References

- 1.Norman WV. Induced abortion in Canada 1974–2005: trends over the first generation with legal access. Contraception. 2012;85(2):185–91. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.06.009. Epub 2011 Aug 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canada Health Act. R.S.C. 1985 c C-6. Available from: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-6/fulltext.html. Accessed 2015 Feb 28.

- 3.Leeson H. Constitutional jurisdiction over health and health care services in Canada. In: McIntosh T, Forest PG, Marchildon GP, editors. The governance of health care in Canada. The Romanow papers. Vol. 3. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 2004. pp. 50–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sethna C, Doull M. Spatial disparities and travel to freestanding abortion clinics in Canada. Womens Stud Int Forum. 2013;38:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaposy C. Improving abortion access in Canada. Health Care Anal. 2010;18(1):17–34. doi: 10.1007/s10728-008-0101-0. Epub 2008 Sep 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggertson L. Abortion services in Canada: a patchwork quilt with many holes. CMAJ. 2001;164(6):847–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abortion access in New Brunswick. Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada; 2015. Available from: www.abortionaccessnb.ca/#!abortion-access/cihk. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferris LE, McMain-Klein M. Small-area variations in utilization of abortion services in Ontario from 1985 to 1992. CMAJ. 1995;152(11):1801–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn S, Wise MR, Johnson L, Anderson G, Ferris LE, Yeritsyan N, et al. Reproductive and gynaecological health. In: Bierman AS, editor. Project for an Ontario women’s health evidence-based report. Vol. 2. Toronto, ON: Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St Michael’s Hospital; 2011. Available from: http://powerstudy.ca/power-report/volume2/reproductive-gynaecological-health. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sethna C, Doull M. Far from home? A pilot study tracking women’s journeys to a Canadian abortion clinic. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(8):640–7. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Canada . Data quality in the Therapeutic Abortion Survey. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; Available from: www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/document/3209_D4_T2_V7-eng.pdf. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics Canada . Table 106-9034. Induced abortions in hospitals and clinics, by age group and area of residence of patient, Canada, provinces and territories, annual. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2009. Available from: www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1069034. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canadian Institute for Health Information . Data tables. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; Available from: www.cihi.ca/CIHI-ext-portal/pdf/internet/TA_11_ALLDATATABLES20140221_EN. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lichtenberg ES, Paul M, Jones H. First trimester surgical abortion practices: a survey of National Abortion Federation members. Contraception. 2001;64(6):345–52. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connell K, Jones HE, Lichtenberg ES, Paul M. Second-trimester surgical abortion practices: a survey of National Abortion Federation members. Contraception. 2008;78(6):492–9. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.011. Epub 2008 Sep 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiegerinck MM, Jones HE, O’Connell K, Lichtenberg ES, Paul M, Westhoff CL. Medical abortion practices: a survey of National Abortion Federation members in the United States. Contraception. 2008;78(6):486–91. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.07.015. Epub 2008 Sep 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connell K, Jones HE, Simon M, Saporta V, Paul M, Lichtenberg ES. First-trimester surgical abortion practices: a survey of National Abortion Federation members. Contraception. 2009;79(5):385–92. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.11.005. Epub 2008 Dec 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG. A clinician’s guide to medical and surgical abortion. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD. Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy. Comprehensive abortion care. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman WV, Soon JA, Maughn N, Dressler J. Barriers to rural induced abortion services in Canada: findings of the British Columbia Abortion Providers Survey (BCAPS) PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dressler J, Maughn N, Soon JA, Norman WV. The perspective of rural physicians providing abortion in Canada: qualitative findings of the BC Abortion Providers Survey (BCAPS) PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guilbert ER, Hayden A, Jones HE, O’Connell White K, Lichtenberg ES, Paul M, et al. First-trimester medical abortion practices in Canada. National survey. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62:e201–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet surveys. The tailored design method. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Canada . Population and dwelling counts, for census metropolitan areas, 2011 and 2006 censuses. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table-Tableau.cfm?LANG=Eng&T=205&S=3&RPP=50. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Statistics Canada . Census metropolitan area (CMA) and census agglomeration (CA). Census dictionary. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/ref/dict/geo009-eng.cfm. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statistics Canada . Table 051-0056. Estimates of population by census metropolitan area, sex and age group for July 1, based on the Standard Geographical Classification (SGC) 2011. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=0510056&tabMode=dataTable&srchLan=-1&p1=-1&p2=9. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desmarais L. Mémoire d’une bataille inachevée. La lute pour l’avortement au Québec 1970–1992. Montreal, QC: Éditions trait d’union; 1999. p. 441. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parent N, St-Cerny A. Le planning des naissances au Québec. Portrait des services et paroles de femmes. Montreal, QC: Fédération du Québec pour le planning des naissances; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orientations ministérielles en matière de planification des naissances. Quebec city, QC: Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux; 1995. Direction générale des programmes, Service à la condition féminine, Direction générale de la planification et de l’évaluation. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guilbert E, Labrecque E, Dubé C, Dumas S, Gaudreault A, Lamontagne R. Plan d’action en matière de planification des naissances. Région de Québec. Quebec city, QC: Régie régionale de la santé et des services sociaux de Québec; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn M, Quirion ME, Parent N, LaRue P, Grabowiecka S, Charbonneau J. Le point sur les services d’avortement au Québec. Montreal, QC: Association canadienne pour la liberté de choix, Fédération du Québec pour le planning des naissances; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Realizing choices. Report of the British Columbia Task Force on Access to Contraception and Abortion Services. Victoria, BC: Minister of Health; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Access to Abortion Services Act. R.S.B.C. 1996. Victoria BC: Government of British Columbia; 1996. Available from: www.bclaws.ca/Recon/document/ID/freeside/00_96001_01. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bill 21—2001: Abortion Services Statutes Amendment Act, 2001. Victoria, BC: Government of British Columbia; 2001. Available from: https://www.leg.bc.ca/36th5th/1st_read/gov21-1.htm. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norman WV, Hestrin B, Dueck R. Access to complex abortion care service and planning improved through a toll-free telephone resource line. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2014;2014:913241. doi: 10.1155/2014/913241. Epub 2014 Feb 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Contraception and Abortion Research Team . Contraception and abortion in BC. Experience guiding research guiding care. Report of proceedings, April 28, 2011. Vancouver, BC: Women’s Health Research Institute; 2011. Available from: www.whri.org/our-research/documents/CARTProceedingsFinal.pdf. Accessed 2016 Mar 10. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Contraception and Abortion Research Team . Contraception and abortion in BC. Experience, guiding research, guiding care. Report of proceedings, May 5, 2014. Vancouver, BC: Women’s Health Research Institute; 2014. Available from: http://cart-grac.ubc.ca/files/2015/01/CART-Proceedings-final-web.pdf. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medical Services Payment Act. S.N.B. 1973 c M-7 as am, s 3(b)(iv).

- 39.General regulation—Medical Services Payment Act. 1989. N.B. Reg 84-20 as am, s 12.

- 40.New Brunswick abortion restriction lifted by Premier Brian Gallant. CBC News. 2014 Nov 27; Available from: www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/new-brunswick-abortion-restriction-lifted-by-premier-brian-gallant-1.2850474. Accessed 2015 Feb 28. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saurette P, Gordon K. The changing voice of the anti-abortion movement. The rise of “pro-woman” rhetoric in Canada and the United States. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press; 2016. p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Health PEI [website] Abortion services. Charlottetown, PE: Health PEI; 2015. Available from: www.healthpei.ca/abortionservices. Accessed 2015 Oct 24. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis R. Abortion training in Canadian family medicine residency programs, 2013; Presented at: National Abortion Federation Annual Meeting, Canadian Providers Day; April 2013; New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roy G, Parvataneni R, Friedman B, Eastwood K, Darney PD, Steinauer J. Abortion training in Canadian obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(2):309–14. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000225915.16083.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steinauer J, Silveira M, Lewis R, Preskill F, Landy U. Impact of formal family planning residency training on clinical competence in uterine evacuation techniques. Contraception. 2007;76(5):372–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paul M, Nobel K, Goodman S, Lossy P, Moschella JE, Hammer H. Abortion training in three family medicine programs: resident and patient outcomes. Fam Med. 2007;39(3):184–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Health Canada . Regulatory decision summary: Mifegymiso. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2015. Available from: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/rds-sdr/drug-med/rds_sdr_mifegymiso_160063-eng.php. Accessed 2015 Sep 8. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones HE, O’Connell White K, Lichtenberg ES, Paul M. Medical abortion provision in the United States [abstract] Contraception. 2014;90(3):301. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kopp Kallner H, Gomperts R, Salomonsson E, Johansson M, Marions L, Gemzell-Danielsson K. The efficacy, safety and acceptability of medical termination of pregnancy provided by standard care by doctors or by nurse-midwives: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. BJOG. 2015;122(4):510–7. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12982. Epub 2014 Jul 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foster AM, Polis C, Allee MK, Simmonds K, Zurek M, Brown A. Abortion education in nurse practitioner, physician assistant and certified nurse-midwifery programs: a national survey. Contraception. 2006;73(4):408–14. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2005.10.011. Epub 2006 Jan 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.KC NP, Basnett I, Sharma SK, Bhusal CL, Parajuli RR, Andersen KL. Increasing access to safe abortion services through auxiliary nurse midwives trained as skilled birth attendants. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2011;9(36):260–6. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v9i4.6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mizuno M. Abortion-care education in Japanese nurse practitioner and midwifery programs: a national survey. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(1):11–4. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.04.016. Epub 2013 May 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webster-Bain D. The successful implementation of nurse practitioner model of care for threatened or inevitable miscarriage. Aust Nurs J. 2011;18(8):30–3. Erratum in: Aust Nurs J 2011;18(9):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones HE, O’Connell White K, Norman WV, Okpaleke C, Guilbert E, Lichtenberg ES, et al. Abortion providers’ resilience to antichoice tactics in the United States and Canada. Contraception. 2014;90(3):300–1. [Google Scholar]