Abstract

Purpose

To obtain insight into employment and insurance outcomes of thyroid cancer survivors and to examine the association between not having employment and other factors including quality of life.

Methods

In this cross-sectional population-based study, long-term thyroid cancer survivors from the Netherlands participated. Clinical data were collected from the cancer registry. Information on employment, insurance, socio-demographic characteristics, long-term side effects, and quality of life was collected with questionnaires.

Results

Of the 223 cancer survivors (response rate 87 %), 71 % were employed. Of the cancer survivors who tried to obtain insurance, 6 % reported problems with obtaining health care insurance, 62 % with life insurance, and 16 % with a mortgage. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis, higher age (OR 1.07, CI 1.02–1.11), higher level of fatigue (OR 1.07, CI 1.01–1.14), and lower educational level (OR 3.22, CI 1.46–7.09) were associated with not having employment. Employment was associated with higher quality of life.

Conclusions

Many thyroid cancer survivors face problems when obtaining a life insurance, and older, fatigued, and lower educated thyroid cancer survivors may be at risk for not having employment.

Keywords: Thyroid cancer, Cancer survivorship, Work, Employment, Population-based study

Introduction

Cancer is no longer considered a death sentence as many of the patients diagnosed with cancer survive due to improved screening, diagnosis, and cancer treatment [1]. This particularly applies for differentiated (papillary and follicular) thyroid cancer survivors, as the 5-year survival rate exceeds 90 % [2] and the 10-year survival rate exceeds 70 %. This high survival rate implicates that survivorship care becomes highly relevant and important for this patient group [3].

For all cancer survivors within the working age, one aspect of survivorship includes the ability to remain in or return to work. Unfortunately, it is known from other cancer types that many cancer survivors experience unwanted changes in their employment status such as working part-time due to cancer [4] and financial status [5] or experience problems upon their return to work [6, 7]. These adverse work outcomes arise due to various factors such as long-term fatigue, unsupportive work environment, and physically heavy work [8, 9].

It is unfortunate that cancer survivors experience such adverse work outcomes because return to work is considered a key aspect of survivorship. Most cancer survivors attribute great meaning to work: it contributes to social inclusion [6], higher self-esteem [10], a better financial situation [5], and it contributes to better quality of life [11]. For those reasons, it is important to prevent adverse work outcomes for all cancer survivors.

Besides adverse work outcomes, it is known from other cancer types that cancer survivors experience socio-economic consequences such as problems with obtaining life and health care insurance [12] or an increase in life or health care insurance premiums [13]. These insurance problems may have a negative impact on cancer survivors’ financial situation and quality of life [13]. Therefore, it is important to draw attention not only to the adverse work outcomes of cancer survivors but also to these other socio-economic consequences of a cancer diagnosis.

Studies among thyroid cancer survivorship including employment and insurance issues are scarce [14], since most work-related survivorship studies focused primarily on breast cancer survivors [8]. However, it is very relevant to study the work and insurance outcomes of thyroid cancer survivors because they are relatively young compared to other cancer survivors and are therefore more often of working age and in a stage of life in which they want to obtain a life insurance and mortgage. Furthermore, they have a high chance of survival, but suffer from higher levels of fatigue compared to the general population [15], which might limit employment possibilities and obtaining the necessary insurances.

Therefore, the aims of the present study are: (1) to examine the consequences of a thyroid cancer diagnosis on work and insurance outcomes, (2) to study which factors are associated with these work outcomes, and 3) to study thyroid cancer survivors with and without paid employment on quality of life outcomes.

Methods

Setting and participants

This study was a cross-sectional population-based study from the southern parts of the Netherlands. The methods of this study have been described in detail elsewhere [15, 16]. Cancer survivors diagnosed with papillary, follicular, or medullary thyroid cancer between 1990 and 2008 and registered in the Eindhoven Cancer Registry (ECR) were eligible for participation. Patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer were excluded because of the very poor prognosis of this type of cancer. Cancer survivors were further excluded for this current study if they: (1) were too ill to participate (n = 31), had unverifiable addresses (n = 70), died prior to the study (n = 6), were not allowed to be contacted as decided by their hospital (n = 86), or were not aged 18–65 years (n = 118). This resulted in a final study population of 257 cancer survivors. The certified Medical Ethical Committee of the Maxima Medical Centre in Veldhoven judged that ethical approval was not required for this study.

Data collection

Data collection was performed within PROFILES (Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship) [16] and started in November 2010. Eligible cancer survivors were informed about the study via a letter from their (former) treating physician, including an informational leaflet containing a link to a secured website, a password, and a login. Cancer survivors who were willing to participate could provide informed consent and fill in the questionnaire via the secured website or by a paper version.

Measures

Two types of measures were used. Clinical and socio-demographic characteristics available through the ECR were linked with self-reported questionnaire data. Characteristics collected by means of the ECR included age at diagnosis, gender, type of thyroid cancer (papillary, follicular, or medullary), stage at diagnosis according to the tumour–node–metastasis (TNM) clinical classification [17], and primary cancer treatment. The questionnaire included the following work-related characteristics: employment status, reason for not being employed, number and type of work changes due to cancer, actual number of hours working, financial difficulties due to cancer, and a question to assess whether patients were concerned about not being able to work if they would become ill again. The questionnaire further included questions on problems with obtaining health care insurance, life insurance, and mortgage and questions on comorbidity, marital status, years since diagnosis, age at time of survey, educational level, depression, anxiety, thyroid-specific health-related quality of life, overall quality of life, global health, and fatigue.

Financial difficulties were measured with a single item from the EORTC health-related quality of life questionnaire and dichotomised into ‘not at all’ and ‘a little’ and compared to ‘quite a bit’ and ‘very much’ [18]. Comorbidity was assessed with the self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire, containing a list of 14 comorbidities (present/not present), and patients were asked whether they perceived each comorbidity as a hindrance in their daily activities at the time of the survey (yes/no) [19].

Anxiety and depression were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [20]. The scale contains 14 items consisting of HADS-A (anxiety, 7 questions) and HADS-D (depression, 7 questions) subscales [21]. All items are rated on a four-point scale (0–3) with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression and anxiety. Thyroid-specific health-related quality of life was assessed with the reliable and valid THYCA-QoL [21]. The THYCA-QoL consists of 24 items (1–4) with lower scores indicating less symptoms and higher quality of life and has seven scales: neuromuscular, voice, concentration, sympathetic, throat/mouth, psychological, and sensory problems. Fatigue was assessed with the validated and reliable Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS) for use among cancer survivors [22], which contains 10 items which are scored on a 5-point scale with higher scores indicating more fatigue. Global health perception was measured with a single item of the Short Form-12 [23] ranging from ‘poor health’ to ‘excellent health’. Overall quality of life was measured on a 7-point Likert scale [18], with higher scores indicating a better quality of life.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 20.0. We considered a p value of ≤0.05 statistically significant. Socio-demographic, clinical, employment, and insurance outcomes were reported using descriptive statistics.

Univariate logistic regression analyses with age, gender, educational level (high (reference) versus medium/low), marital status (married or living with partner (reference) versus no partner), cancer diagnosis (papillary (reference) versus follicular), cancer treatment (surgery only (reference) versus surgery and additional treatment), cancer stage [1 and 2 (reference) versus 3 and 4], fatigue, anxiety, depression, and comorbidity (no comorbidity (reference) versus one or more comorbidities) were conducted to identify associations with not having employment. We choose these factors as these were found to be associated with employment among other groups of cancer survivors [8, 9]. Factors that were statistically significant were entered in a multivariate logistic regression analysis unless the correlation coefficient between two variables was ≥0.7 to prevent multicollinearity. The model was built in three blocks: (1) socio-demographic variables, (2) clinical variables, (3) long-term side effects variables, and (4) demographic, clinical, and long-term side effects variables. Odd ratios (ORs) will be reported with 95 % confidence intervals (CI).

Differences between thyroid cancer survivors with and without paid employment on the thyroid-specific health-related quality of life scales, global health, and quality of life were analysed using Student’s t test when variables are normally distributed or the Mann–Whitney U test otherwise. To test whether variables were normally distributed, we used Kolmogorov–Smirnov test of normality (cut-off p value ≤0.05).

Results

Of the 257 cancer survivors, 223 returned the questionnaire (response rate 87 %). Table 1 shows the sample characteristics. The mean age was 49.5 (standard deviation ± 9.8) years, and 22 % were male. Almost three-quarter (71 %) of the patients were diagnosed with stage 1 disease. Surgery followed by 131I therapy (70 %) was the most common treatment. The median time since diagnosis was 9.0 years.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of thyroid cancer survivors

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||

| Age in years at time of study (mean ± SD) | 49.5 ± 9.8 | N = 223 |

| Gender [N (%) male] | 49 (22) | N = 223 |

| Marital status [N (%) married or living with partner] | 187 (84) | N = 223 |

| Educational level [N (%)] | ||

| High | 68 (31) | N = 222 |

| Intermediate | 108 (49) | |

| Low | 46 (21) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Years since initial diagnosis (mean ± SD) | 9.9 ± 5.2 | N = 223 |

| Type of thyroid cancer [N (%)] | ||

| Papillary | 171 (77) | N = 213 |

| Follicular | 41 (19) | |

| Medullary | 9 (4) | |

| Primary treatment [N (%)] | ||

| Surgery | 63 (29) | N = 223 |

| Surgery + 131I ablation | 145 (70) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | |

| Stage at diagnosis [N (%)] | ||

| 1 | 158 (72) | N = 220 |

| 2 | 26 (12) | |

| 3 | 29 (13) | |

| 4 | 7 (3) | |

| Number of comorbidity at time of study [median (range)] | 0 (0–9) | N = 223 |

| Fatigue (FAS) (mean ± SD) | 21.8 ± 7.6 | N = 212 |

| Anxiety (HADS) (mean ± SD) | 4.7 ± 3.9 | N = 215 |

| Depression (HADS) (mean ± SD) | 3.2 ± 3.0 | N = 215 |

SD standard deviation. Education: high (pre-university education, high vocational education, university), intermediate (lower general secondary education or vocational education), low (no or primary school). Stage: tumour–node–metastasis clinical classification. FAS Fatigue Assessment Scale. HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Higher score means higher fatigue, anxiety, and depression. Numbers do not always add up to 223 due to missing values. Percentages do not always add up due to rounding

Employment outcomes and work changes

Seventy-one per cent of the thyroid cancer survivors were employed (Table 2). Reasons for not being employed were disability (33 %), early retirement (e.g. due to reconstitution) (14 %), no job (6 %), or other (e.g. voluntary unemployed) (46 %). One-third (33 %) reported work changes due to cancer, i.e. working less hours (16 %), being disabled (9 %), being fired (5 %), stopped working (4 %), re-educated (3 %), early pension (1 %), or working more hours (1 %) as work change due to cancer.

Table 2.

Employment outcomes among thyroid cancer survivors

| Employment outcomes | ||

| Employment at this moment [N (%) employed] | 154 (71) | N = 217 |

| Reason for no employment [N (%)] | ||

| No job | 4 (6) | N = 63 |

| Work disabled | 21 (33) | |

| (Early) retirement | 9 (14) | |

| Other | 29 (46) | |

| Disability percentage [median (range)] | 100 (30–100) | N = 19 |

| Change in employment status due to cancer [N (%) yes] | 74 (33) | N = 223 |

| Type of work changes due to cancer [N (%)]a | ||

| Fired | 10 (5) | N = 87 |

| Disability | 21 (9) | |

| Early pension | 2 (1) | |

| Stopped working | 9 (4) | |

| Re-educated | 6 (3) | |

| Working more hours | 3 (1) | |

| Working less hours | 36 (16) | |

| If employed, number of hours working (mean ± SD) | 28 ± 12 | N = 156 |

| Financial difficulties due to cancer [N (%) yes] | 21 (10) | N = 219 |

| Concerned about not being able to work if become ill again | ||

| Totally agree and agree | 25 (22) | N = 158 |

| Neutral | 24 (15) | |

| Totally disagree and disagree | 99 (62) |

SD standard deviation. Numbers do not always add up to 223 due to missing values. Percentages do not always add up due to rounding

aThe total number of type of work changes is higher compared to the number of change in employment status due to cancer since some participants reported more than one type of work change due to cancer

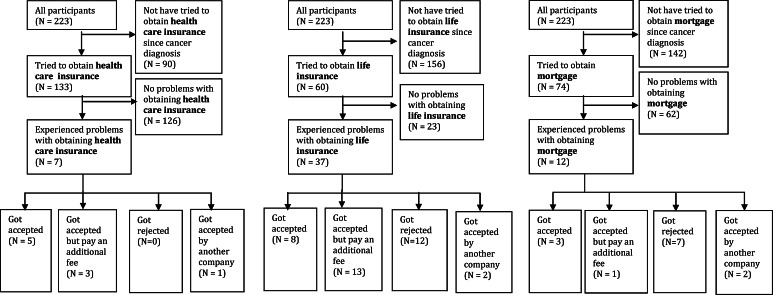

Insurance outcomes

Of those thyroid cancer survivors who tried to obtain an insurance after their cancer diagnosis, 62 % (n = 37) reported obtaining problems with a life insurance, followed by problems with obtaining a mortgage (16 %; n = 12) or health care insurance (6 %; n = 7) (Fig. 1). Of the 62 % of patients who reported problems with obtaining life insurance, 37 % got accepted but had to pay an additional fee, 34 % got rejected, 23 % got accepted eventually, and 6 % got accepted by another company. Of the 16 % of the patients who reported problems with obtaining mortgage, 54 % got rejected, 23 % got accepted eventually, 15 % got accepted by another company, and 8 % got accepted but pay an additional fee. Of the 6 % of the patients who reported problems with obtaining health care insurance, 56 % got accepted eventually, 33 % got accepted but pay an additional fee, and 11 % got accepted by another company.

Fig. 1.

Insurance outcomes among thyroid cancer survivors. Numbers do not always add up because some participants did not fill in the questions correctly (e.g. some participants answered ‘no’ on the question whether he/she experienced problems with obtaining a health care insurance, but did fill in the question what kind of problem he/she experienced)

Factors associated with not having employment

Factors associated with not having employment in the univariate logistic regression analysis were: higher age at time of survey [odds ratio (OR) 1.09, (95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.13), p < 0.01], lower educational level [OR 4.67, (95 % CI 2.35–9.29), p < 0.01], unfavourable cancer stage [OR 2.23, (95 % CI 1.06–4.72), p = 0.04], higher level of fatigue [OR 1.08, (95 % CI 1.03–1.12), p = 0.001], higher level of anxiety [OR 1.08, (95 % CI 1.01–1.17), p = 0.04], higher level of depression [OR 1.13, (95 % CI 1.03–1.240, p = 0.01], and reporting one or more comorbidities [OR 3.99, (95 % CI 2.15–7.42), p < 0.01]. Gender, marital status, type of tumour or the treatment were not related to not having employment.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of model 1, consisting of socio-demographic variables, showed that higher age at time of survey [OR 1.07, (95 % CI 1.03–1.11), p < 0.001] and lower educational level were associated with higher chance of not having employment [OR 3.67 (95 % CI 1.78–7.58), p < 0.01]. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of model 2, including clinical variables showed that reporting one or more comorbidities was associated with a higher chance of not having employment [OR 3.58 (95 % 1.90–6.71), p < 0.01]. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of variables of model 3, including long-term side effect variables, showed that a higher level of fatigue was associated with a higher chance of not having employment [OR 1.07, CI (95 % CI 1.01–1.12), p = 0.02] (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic multivariate models of factors associated with not having employment

| Model 1 OR (95 % CI) | Model 2 OR (95 % CI) | Model 3 OR (95 % CI) | Model 1 + 2 + 3 OR (95 % CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: demographic variables | ||||

| Age at survey | 1.07 (1.03–1.11)** | – | – | 1.07 (1.02–1.11)** |

| Educational level | 3.67 (1.78–7.58)** | – | – | 3.22 (CI 1.46–7.09)** |

| Block 2: clinical variables | ||||

| Cancer stage | – | 2.02 (0.92–4.43) | – | 0.99 (0.39–2.51) |

| Comorbidity | – | 3.58 (1.90–6.71)** | – | 2.05 (0.99–4.24) |

| Block 3: long-term side effects variables | ||||

| Fatigue (FAS) | – | – | 1.07 (1.01–1.12)* | 1.07 (CI 1.01–1.14)* |

| Depression (HADS) | – | – | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) |

| Anxiety (HADS) | – | – | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) | 1.02 (0.91–1.15) |

Bold values indicate p < 0.05

Employed versus not having employment

Educational level: high (reference) versus medium/low. Cancer stage: 1 and 2 (reference) versus 3 and 4. Comorbidity: no comorbidity (references) versus one or more comorbidities

OR odds ratio, 95 % CI 95 % confidence interval, FAS Fatigue Assessment Scale, HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01

In the final multivariate logistic regression model consisting of a combination of model 1, 2 and 3, higher age [OR 1.07, (95 % CI 1.02–1.11), p < 0.01], a higher level of fatigue [OR 1.07, CI (95 % CI 1.01–1.14), p = 0.02], and a lower educational level [OR 3.22, (95 % CI 1.46–7.09), p ≤0.01] remained associated with not having employment (Table 3).

Quality of life and employment

Employed cancer survivors scored overall better on the thyroid cancer-specific HRQoL scales as well as on global health and overall quality of life (Table 4). Employed thyroid cancer survivors scored significantly better compared to thyroid cancer survivors without employment on neuromuscular problems (20.1. ± 19.5 vs 32.1 ± 25.9, p < 0.01), voice problems (7.7 ± 15.2 vs 16.1 ± 24.9, p = 0.02), and on overall quality of life (69.4 ± 16.5 vs 61.7 ± 20.4, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Quality of life outcomes of thyroid cancer survivors with and without paid employment

| Health-related characteristics | Employment | Without employment |

|---|---|---|

| THYCA-QoL | ||

| Neuromuscular problems (mean ± SD) | 20.1 ± 19.5 | 32.0 ± 25.9** |

| Voice problems (mean ± SD) | 7.6 ± 15.2 | 16.1 ± 24.9* |

| Concentration problems (mean ± SD) | 16.4 ± 21.5 | 18.8 ± 24.6 |

| Sympathetic problems (mean ± SD) | 16.8 ± 24.4 | 25.8 ± 3 0.2 |

| Throat problems (mean ± SD) | 10.4 ± 14.6 | 18.2 ± 23.2 |

| Psychological problems (mean ± SD) | 13.6 ± 15.1 | 18.8 ± 20.7 |

| Sensory problems (mean ± SD) | 13.3 ± 18.0 | 19.6 ± 22.4 |

| Overall quality of life (mean ± SD) | 69.4 ± 16.5 | 61.7 ± 20.4** |

THYCA-QoL: thyroid-specific health-related quality of life. Higher score means more problems. QOL: overall quality of life on scale 0–100. Higher score means better QOL. Numbers do not always add up to 223 due to missing values

** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05

Discussion

The purpose of our study was: (1) to obtain insight into employment and insurance outcomes of thyroid cancer survivors, (2) to examine factors associated with not having employment, and (3) to study thyroid cancer survivors with and without paid employment on quality of life outcomes. Our finding that many thyroid cancer survivors face problems when obtaining a life insurance and that older, fatigued, and lower educated thyroid cancer survivors may be at risk for not being employed, which may both negatively impact cancer survivors’ financial situation and quality of life.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our study include the use of a population-based sample with a high response rate, which implies that our findings can be generalised to thyroid cancer survivors at large. Furthermore, most studies on cancer and work considered the return to work of employed cancer survivors at diagnosis only, excluding unemployed cancer patients, who just might be at a greater risk of adverse outcomes. Our study also had some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to draw conclusions on the causal effect of the association. However, it might be possible that the identified factors might lead to a higher risk of not being employed rather than being a consequence of not being employed. This assumption is based on the notion that the relationship between fatigue as a cause of thyroid cancer treatment has been well established [15] and the nature of the other factors included in our model (e.g. age). This should therefore be studied with a longitudinal design in future studies.

Second, we were not able to include work-related factors such as physical work and type of occupation (e.g. Ref. [8]) that have been found to be associated with employment in other cancer types. For that reason, our model might not be optimal in explaining all factors that are associated with employment among thyroid cancer survivors. Work-related factors should therefore be included in future studies. Finally, we did not collect data on the year in which a thyroid cancer survivor experienced problems with obtaining a health care or life insurance, or a mortgage. In recent years, many changes in the rules and regulations of insurance companies have taken place. These regulations largely influence the extent to which problems are experienced. We are therefore not able to draw conclusions of who are at the highest risk of experiencing problems with obtaining these insurances and mortgage and recommend including this aspect in future studies.

Interpretation of findings

In contrast to other cancer types, long-term thyroid cancer survivors have comparable employment rates to the general population [24]. An explanation for this finding might be that most thyroid cancer survivors are relatively young and have better long-term physical and psychological outcomes due to less aggressive forms of cancer treatment (no external radiotherapy or chemotherapy). For instance, long-term thyroid cancer survivors (>10 years) do not have elevated levels of fatigue compared to norm values, in contrast to short-term thyroid cancer survivors (<10 years) [15] and to both short-term and long-term survivors of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [25].

Thirty-three per cent of the cancer survivors reported work changes due to cancer, which is higher compared to a study among colorectal and haematological cancer survivors (28 % experienced work changes) [26] and lower compared to a study among prostate, endometrial, and haematological cancer survivors [12]. This latter finding could be explained by the fact that we excluded all patients aged ≥65 years, excluding the work change of retirement.

Higher age, lower educational level, and a higher level of fatigue were associated with not having employment irrespective of clinical factors. This finding is consistent with the literature of other cancer types (e.g. [9]). For instance, a Danish study among haematological cancer survivors found that higher age and lower educational level was associated with not returning to work [27]. Another Danish study among breast cancer survivors found that lower educational level was associated with unemployment [28]. In contrast to other cancer types, we did not find that cancer treatment was associated with employment (e.g. [27]). This finding could also be explained by the less aggressive forms of cancer treatment of thyroid cancer survivors.

We found that only a small proportion of the cancer survivors had problems with obtaining a health care insurance or mortgage, which is consistent with a study among both colorectal cancer survivors and haematological cancer survivors [12]. This finding can be explained by the Dutch health insurance system, which forbids by law risk selection for the basic health insurance scheme based on someone’s medical history. In contrast to the study among both colorectal and haematological cancer survivors, we found that much more cancer survivors had problems with obtaining a life insurance (62 vs 20 %) [12]. Additionally, especially for employed thyroid cancer survivors the effect of not being able to obtain a life insurance might be more prominent as the security for their income is more depending on this life insurance compared to unemployed cancer survivors.

Our study showed that employed thyroid cancer survivors report better global health and overall quality of life compared to thyroid cancer survivors without a paid job, which is consistent with the literature [11]. Our finding that thyroid cancer survivors without employment experience more problems on neuromuscular and voice level compared to employed thyroid cancer survivors indicates that a certain level of physical functioning is needed to be able to work. Surprisingly, we did not find differences between employed thyroid cancer survivors and thyroid cancer survivors without employment on concentration problems, while concentration problems have often been reported as a problem for returning to work in other cancer types [29].

Recommendations for further research and practice

As the employment rate of thyroid cancer survivors is comparable to the general population, interventions to enhance employment for all thyroid cancer survivors seem not needed. However, as in other cancers it is important to reach thyroid cancer survivors who are older, have a lower educational level, and have a higher level of fatigue with an appropriate intervention that will reduce their risk of not having employment. For instance, such an intervention could consist of cognitive behaviour therapy, as it has been proven effective in reducing fatigue among cancer survivors [30]. However, its effect on employment is unknown. Furthermore, health care professionals should be aware of the socio-economic implications of a thyroid cancer diagnosis: in particularly which patients have a higher risk of not having employment and that survivors may face problems with obtaining a life insurance. When health care professionals are aware of these implications, they will be able to point out problems and refer patients to appropriate interventions and authorities.

A recommendation for further research is to include work-related parameters such as type of work or previous unemployment spells in the study. In this way, a model that explains employment would most likely be more complete and could provide further information on which patients are at the highest risk and which parameters should be addressed in an intervention. In addition, on the traditional work outcome, employment rate, thyroid cancer survivors have comparable outcomes compared to the general population. However, as unemployment often is considered the tip of the iceberg of possible adverse work outcomes, it would be very relevant to study subtle work outcomes such as quality of working life, work functioning, and work-home balance in the future.

In addition, a recommendation for further research is to use a longitudinal design to examine whether the earlier identified factors also have a causal relation with employment and to obtain insight in labour market transitions. The first is important for the development of interventions; the latter for a better understanding of employment, as being employed is not a fixed event, but many transitions may occur in the working life course.

Acknowledgments

The data collection of this study was funded by the Comprehensive Cancer Centre South, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, and a Medium Investment Grant from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO#480-08-009). This work was supported by the Work Disability Prevention Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Strategic Training Program Grant (FRN: 53909). This work was supported by COST Action IS1211 CANWON.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

SJ Tamminga declares that she has no conflict of interest. U Bültmann declares that she has no conflict of interest. O Husson declares that she has no conflict of interest. JLP Kuijpens declares that he has no conflict of interest. MHW Frings-Dresen declares that she has no conflict of interest. AGEM de Boer declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

O. Husson—Formally at Center of Research on Psychology in Somatic Diseases, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands.

Contributor Information

S. J. Tamminga, Phone: +31 20 5663279, Email: S.J.Tamminga@amc.nl

O. Husson, Email: Olga.Husson@radboudumc.nl

References

- 1.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: A follow-up study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94(1):39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Zwan JM, Mallone S, van Dijk B, Bielska-Lasota M, Otter R, Foschi R, Baudin E, Links TP, Rarecare WG. Carcinoma of endocrine organs: Results of the RARECARE project. European Journal of Cancer. 2012;48(13):1923–1931. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mols F, Thong MS, Vreugdenhil G, van de Poll-Franse LV. Long-term cancer survivors experience work changes after diagnosis: Results of a population-based study. Psychooncology. 2009;18(12):1252–1260. doi: 10.1002/pon.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syse A, Tretli S, Kravdal O. Cancer’s impact on employment and earnings—A population-based study from Norway. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2(3):149–158. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamminga SJ, de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, Frings-Dresen MHW. Breast cancer survivors’ views of factors that influence the return-to-work process—A qualitative study. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health. 2011 doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tiedtke C, Dierckx de Casterle B, Donceel P, de Rijk A. Workplace support after breast cancer treatment: Recognition of vulnerability. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2014 doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.982830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Muijen P, Weevers NL, Snels IA, Duijts SF, Bruinvels DJ, Schellart AJ, Van der Beek AJ. Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2013;22(2):144–160. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feuerstein M, Todd BL, Moskowitz MC, Bruns GL, Stoler MR, Nassif T, Yu X. Work in cancer survivors: A model for practice and research. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2010;4(4):415–437. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tiedtke C, de Rijk A, Dierckx de Casterle B, Christiaens MR, Donceel P. Experiences and concerns about ‘returning to work’ for women breast cancer survivors: A literature review. Psychooncology. 2010;19(7):677–683. doi: 10.1002/pon.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer. 2005;41(17):2613–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mols F, Thong MS, Vissers P, Nijsten T, van de Poll-Franse LV. Socio-economic implications of cancer survivorship: Results from the PROFILES registry. European Journal of Cancer. 2012;48(13):2037–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meneses K, Azuero A, Hassey L, McNees P, Pisu M. Does economic burden influence quality of life in breast cancer survivors? Gynecologic Oncology. 2012;124(3):437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husson O. Information provision and patient reported outcomes in cancer survivors: With a special focus on thyroid cancer. Tilburg: Tilburg University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husson O, Nieuwlaat WA, Oranje WA, Haak HR, van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F. Fatigue among short- and long-term thyroid cancer survivors: Results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Thyroid. 2013;23(10):1247–1255. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Poll-Franse LV, Horevoorts N, van Eenbergen M, Denollet J, Roukema JA, Aaronson NK, Vingerhoets A, Coebergh JW, de Vries J, Essink-Bot ML, Mols F, Profiles Registry G The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry: Scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. European Journal of Cancer. 2011;47(14):2188–2194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobin LH, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 6. New Jersey: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: A new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2003;49(2):156–163. doi: 10.1002/art.10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavian. 1983;67(6):361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husson O, Haak HR, Mols F, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Nieuwlaat WA, Reemst PH, Huysmans DA, Toorians AW, van de Poll-Franse LV. Development of a disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaire (THYCA-QoL) for thyroid cancer survivors. Acta Oncologica. 2013;52(2):447–454. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.718445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michielsen HJ, De Vries J, Van Heck GL. Psychometric qualities of a brief self-rated fatigue measure: The Fatigue Assessment Scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2003;54(4):345–352. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Verrips E. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998;51(11):1055–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Netherlands. (2011). In Dutch: Central bureau voor de statistiek CBS. www.cbs.nl

- 25.Oerlemans S, Mols F, Issa DE, Pruijt JH, Peters WG, Lybeert M, Zijlstra W, Coebergh JW, van de Poll-Franse LV. A high level of fatigue among long-term survivors of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: Results from the longitudinal population-based PROFILES registry in the south of the Netherlands. Haematologica. 2013;98(3):479–486. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.064907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mols F, Thong MS, Vreugdenhil G, van de Poll-Franse LV. Long-term cancer survivors experience work changes after diagnosis: Results of a population-based study. Psycho-oncology. 2009;18(12):1252–1260. doi: 10.1002/pon.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horsboel TA, Nielsen CV, Nielsen B, Jensen C, Andersen NT, de Thurah A. Type of hematological malignancy is crucial for the return to work prognosis: A register-based cohort study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2013;7(4):614–623. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlsen K, Ewertz M, Dalton SO, Badsberg JH, Osler M. Unemployment among breast cancer survivors. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1403494813520354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munir F, Burrows J, Yarker J, Kalawsky K, Bains M. Women’s perceptions of chemotherapy-induced cognitive side affects on work ability: A focus group study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19(9–10):1362–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gielissen MF, Verhagen S, Witjes F, Bleijenberg G. Effects of cognitive behavior therapy in severely fatigued disease-free cancer patients compared with patients waiting for cognitive behavior therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(30):4882–4887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]