Abstract

Patients with hypoparathyroidism have low circulating parathyroid (PTH) levels and higher cancellous bone volume and trabecular thickness. Treatment with PTH(1-84) was shown to increase abnormally low bone remodeling dynamics. In this work, we studied the effect of 1yr or 2yr PTH(1-84) treatment on cancellous and cortical bone mineralization density distribution (Cn. and Ct.BMDD) based on quantitative backscattered electron imaging (qBEI) in paired transiliac bone biopsy samples. The study cohort comprised 30 adult hypoparathyroid patients (14 treated for 1yr/16 treated for 2yr).

At baseline, Cn.BMDD was shifted to higher mineralization densities in both treatment groups (average degree of mineralization Cn.CaMean +3.9% and +2.7%, p<0.001) compared to reference BMDD. After 1yr PTH(1-84), Cn.CaMean was significantly lower than that at baseline (-6.3%, p<0.001), while in the 2yr PTH(1-84) group Cn.CaMean did not differ from baseline. Significant changes of Ct.BMDD were observed in the 1yr treatment group only. The change in histomorphometric bone formation (mineralizing surface) was predictive for Cn.BMDD outcomes in the 1yr PTH(1-84) group, but not in the 2yr PTH(1-84) group.

Our findings suggest higher baseline bone matrix mineralization consistent with the decreased bone turnover in hypoparathyroidism. PTH(1-84) treatment caused differential effects dependent on treatment duration which were consistent with the histomorphometric bone formation outcomes. The greater increase in bone formation during the first yr of treatment was associated with a decrease in bone matrix mineralization, suggesting that PTH(1-84) exposure to the hypoparathyroid skeleton has the greatest effects on BMDD early in treatment.

Keywords: hypoparathyroidism, bone mineralization density distribution (BMDD), quantitative backscattered electron imaging (qBEI), transiliac bone biopsy

Introduction

Hypoparathyroidism is characterized by the absence or deficiency of parathyroid hormone which is accompanied by low serum calcium levels and other biochemical abnormalities (1, 2). It is well-established that bone turnover levels are low (3, 4), in association with structural skeletal alterations including higher cancellous bone volume and trabecular thickness, but lower bone surface per volume (3). Increased bone mineral density (BMD) has been reported as compared to age- and sex-matched controls (5, 6) and postmenopausal bone loss may also be attenuated (7). Noteworthy, Seeman and colleagues suggested that PTH deficiency might protect against age-related bone loss, however their study did not allow conclusions on the related mechanism (decelerated loss or higher peak bone mass) (5). Irrespective of skeletal alterations no increase in fragility fractures has been observed with hypoparathyroidism.

Administration of PTH (1-84) has led to improvements in calcium metabolism (2, 8, 9, 10, 11) and increased biochemical and histomorphometric indices of skeletal dynamics (12, 13, 14). Yet how PTH deficiency and replacement effects bone mineralization, an important characteristic of the bone material and a critical determinant of bone strength, is unknown. We hypothesized that PTH(1-84) treatment in patients with hypoparathyroidism would alter the bone mineralization density distribution (BMDD) in the cancellous and cortical compartments. To address this question, paired transiliac bone biopsy samples from hypoparathyroid patients before (baseline) and after treatment with PTH(1-84) were examined by quantitative backscattered electron imaging (qBEI).

Materials & Methods

Patients & Biopsy samples

The cohort consisted of hypoparathyroid patients who were treated with PTH(1-84) for one year (n=14, PTH(1-84)-1yr) or for two years (n=16, PTH(1-84)-2yrs) (12). Changes in histomorphometric structure and bone turnover were previously described (12). The baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. Paired biopsy samples were obtained from each group at baseline and after either 1yr PTH(1-84) treatment or 2yrs PTH(1-84) treatment. The two treatment groups comprised different individuals (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of the two Hypoparathyroid Cohorts at Baseline.

| Hypoparathyroid cohorts at Baseline | Normal range1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1yr treatment group, baseline n=14 | 2yrs treatment group, baseline n=16 | baseline diff (p-value) | ||

| Age (yrs) | 55 (41; 61) | 47 (40; 60) | 0.575 (n.s.) | |

| Sex | Male: 4 Female: 10 (premeno 5, postmeno 5) |

Male: 4 Female: 12 (premeno 7, postmeno 5) |

1.000 (n.s.) | |

| Etiology of hypoparathyroidism | 9 postsurgical 5 autoimmune |

10 postsurgical 6 autoimmune |

0.781 (n.s.) | |

| Duration (yrs) of hypoparathyroidism | 16.0 (5.0; 40.0) | 17.0 (5.5; 28.5) | 0.739 (n.s.) | |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 8.2 (7.38.8) | 8.5 (8.0;9.1) | 0.343 (n.s.) | 8.5-10.2 |

| PTH (ng/L) | 3 (2;2) | 4 (2;6.4) | 0.548 (n.s) | 10-65 |

| TRACP-5b (U/L) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.6 (1.2) | 0.731 (n.s.) | 2.6-4.0 |

| OC (ng/mL) | 10.3 (5.6) | 9.9 (6.8) | 0.939 (n.s.) | 8.8-55 |

| s-CTX (ng/mL) | 0.3 (0.2; 0.3) | 0.2 (0.1; 0.4) | 0.827 (n.s.) | 0.1-1.4 |

| BAP (U/L) | 26.6 (7.4) | 30.0 (17.8) | 0.512 (n.s.) | 11-43 |

| P1NP (ng/mL) | 32.9 (25.0; 44.0) | 25.3 (20.5; 41.8) | 0.234 (n.s.) | 16-96 |

Data are mean (SD) or median (25th; 75th percentiles). p-values are based on t-test or Mann-Whitney comparison or Fisher Exact tests (latter for category variables) of groups at baseline. TRACP-5b = osteoclast-derived 5b isoform of TRACP; OC = ostecalcin; s-CTX = Carboxy-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of bone collagen; BAP = bone specific alkaline phosphatase; P1NP = Procollagen type 1 amino-terminal propeptide

Biochemical measurements and normal range from previous work (12).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of biopsy procedure in the two treatment groups.

Quantitative backscattered electron imaging (qBEI)

Backscattered electron images display an atomic Z number contrast of the target material. The higher the average Z number, the higher are the backscatter electron intensities and the brighter the pixel grey levels (GL) in the image (details in Figure 1). Assuming that no heavy elements are present in the bone tissue, the GLs can be transferred to weight% mineral and/or weight% Ca values as described in detail in our previous work (15, 16). The GL-histograms derived from the calibrated backscattered electron images of bone tissue provide information about the frequency distribution of pixel sized bone areas with a certain average atomic Z number/Ca content.

The qBEI images were acquired at a digital scanning electron microscope (DSM 962, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) based on following microscope settings: an accelerating voltage of 20 kV, a probe current of 110 ± 0.4 pA (measured with a Faraday cup connected to a pico ampere-meter), a working distance of 15mm, and a scan speed of 100 seconds per frame. Backscattered electrons were collected by a four-quadrant semiconductor backscattered electron detector. The entire bone tissue area (trabecular and cortical compartments) was recorded in a series of images with a 50× nominal magnification corresponding to a scanned bone area of about 2 mm × 2.5 mm. Employing carbon (Z=6) and aluminum (Z=13) as reference materials the contrast and brightness control of the DSM was adjusted in such way that the histogram peak of the carbon target was located at 25±1 GL-index and that of aluminum at 225±1 GL-index. GL-histograms obtained form cancellous and cortical bone separately with a bin width of one GL-step were further transformed to weight % Ca values resulting in weight % Ca histograms (so called bone mineralization density distribution, BMDD) with a bin width of 0.17 weight% Ca (Figure 1). We used five BMDD parameters to characterize the BMDD curves: CaMean= the weighted mean Ca-concentration of the bone area; CaPeak= the peak position of the histogram, indicating the most frequently measured calcium concentration; CaWidth= the full width at half maximum of the distribution, describing the heterogeneity in matrix mineralization; CaLow= the percentage of lowly mineralized bone (<17.68 weight % Ca - the calcium concentration at the 5th percentile of our reference BMDD (17)); CaHigh= the percentage of highly mineralized bone areas (>25.30 wt% Ca - the calcium concentration at the 95th percentile of the reference BMDD (17)). For characterization of cortical BMDD, the two cortical plates were analyzed separately and subsequently the arithmetic mean (Ct.) of the two plates was calculated for each sample, as recently described (18). For the interpretation of qBEI outcomes, we correlated the changes in BMDD variables with changes in mineralizing surface per bone surface (MS/BS), a primary index for bone formation that was measured in the identical bone biopsy samples in a previous work (12).

Statistical Analyses

The data are presented by median (25th; 75th percentiles) (obtained from SigmaPlot 2004 for Windows Version9.0). Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat for Windows Version 2.03 (SPSS Inc.). The effects of treatment were analyzed by non-parametric paired (Wilcoxon signed rank) tests. Comparison to reference BMDD data or comparison among the two groups after treatment with PTH(1-84) is based on non-parametric Mann Whitney rank sum tests. Correlation analyses were performed using either Pearson Product Moment correlation or (in case of non-normally distributed data) Spearman rank order correlation.

Results

Baseline BMDD

qBEI images and corresponding BMDD curves from a typical hypoparathyroid patient at baseline and after treatment with PTH(1-84) can be seen in Figure 1. At baseline, no significant difference between the two cohorts in any of the Cn. or Ct.BMDD variables (rank sum tests all p>0.05) could be observed.

The baseline BMDD variables showed relatively high inter-individual variation within the patients group. In particular, correlation analyses showed that none of the biochemical variables P1NP, ALP, OC, s-CTX, or TRACP-5b were predictive for the level of CaMean within the hypoparathyroid patients group (all correlations p>0.05).

In average, both baseline groups revealed a significant shift of the Cn.BMDD to higher calcium concentrations compared to reference BMDD. Cn.CaMean (+3.9% and +2.7%, p<0.001), Cn.CaPeak (+2.7% and +2.3%, p<0.001), and Cn.CaHigh (2.8-fold and 2.6-fold, p<0.001) were significantly higher, while Cn.CaLow was lower than normal (-13%, p<0.01 and -21%, p<0.05 for 1yr PTH(1-84) and 2yrs PTH(1-84), respecetively) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

qBEI images of overview and detail of cancellous bone from representative paired bone biopsy samples from two hypoparathyroid patients (left before and right after 1 year or 2 years PTH(1-84) treatment) with corresponding BMDD curves. The brighter the grey level of the pixel in the image, the higher is the local calcium concentration. The baseline samples from both patients reflect the decreased bone turnover by relatively low variation in bone matrix mineralization. The biopsy after 1 yr PTH(1-84) reveals a high variation in matrix mineralization (mirrored by the occurrence of different grey levels, in particular a high percentage of relatively dark grey levels), and shows features similar to trabecular tunneling and high cortical porosity, as quantified in the previous work (12). In the sample after 2yrs PTH(1-84), bone matrix mineralization reveals lower variation than the 1yr treated sample, as specifically seen by the paucity of areas of low matrix mineralization.

Cortical BMDD outcomes of both treatment groups at baseline were not significantly different to reference Ct.BMDD variables.

PTH effects on BMDD group medians

Group median outcomes and comparisons are summarized in Figure 2. 1yr-PTH(1-84) treatment caused significant decreases in Cn.CaMean (-6.3%, P<0.001) as well as significant increases in Cn.CaWidth (+30%, p<0.01) and Cn.CaLow (+79%, p<0.001) in cancellous bone versus baseline. Similarly in cortical bone, Ct.CaMean was significantly decreased (-2.7%, p<0.05), while Ct.CaWidth (+9.9%, p<0.05) and Ct.CaLow (+55%, p<0.001) were both increased versus baseline.

2yrs-PTH(1-84) treatment caused a significant effect only in Cn.CaWidth (+19%, p<0.05) while all other Cn. and Ct. BMDD outcomes were not significantly different from baseline.

Comparison of the treated patient groups to reference cancellous BMDD showed that after 1yr PTH(1-84), Cn.CaMean and Cn.CaPeak were within normal range, while Cn.CaWidth (+26%, p<0.001), Cn.CaLow (+55%, p<0.01), and Cn.CaHigh (+90%, p<0.05) were increased compared to reference values. The group treated for 2yrs with PTH(1-84) revealed no difference from the reference BMDD for Cn.CaMean, while Cn.CaPeak (+1.9%, p<0.01), Cn.CaWidth (+19%, p<0.01), and Cn.CaHigh (2.3-fold, p<0.001) were increased compared to reference values.

Comparison of the treated patient groups to reference cortical BMDD showed that after 1yr PTH(1-84) Ct.CaMean was decreased (-2.5%, p<0.05), while Ct.CaWidth (+16%, p<0.01) and Ct.CaLow (+55%, p=0.001) were increased. After 2yrs with PTH(1-84), Ct.CaWidth (+9.2%, p<0.05) and Ct.CaHigh were increased (+62%, p<0.05).

Comparison among the treated groups showed significantly different Cn. and Ct.CaLow which were 43% and 39% (both p<0.05) higher, while Ct.CaMean was lower (-2.7%, p=0.05) in the 1yr PTH(1-84) compared to the 2yrs PTH(1-84) group (Figure 2).

Intra-individual changes in BMDD and relation to changes in histomorphometric bone formation and volume due to PTH(1-84) treatment

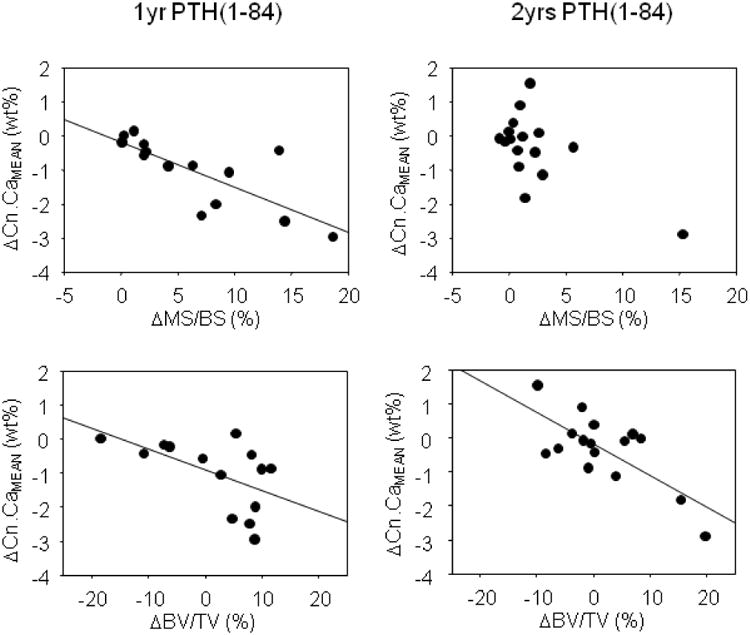

Intra-individual changes due to PTH(1-84) treatment and their correlation with changes in previously measured histomorphometric indices are shown in Table 2 and Figures 3 and 4.

Table 2. Relationship between changes in cancellous BMDD variables and histomorphometric cancellous bone formation (MS/BS) and bone volume (BV/TV).

| change in BMDD variable | predicted by change in histomorphometric variable | regression coefficient | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1yr PTH(1-84) treatment | Cn.CaMean | MS/BS BV/TV |

-0.77 -0.55 |

0.001 0.04 |

| Cn.CaPeak | MS/BS BV/TV |

-0.67 -0.57 |

0.009 0.04 |

|

| Cn.CaWidth | MS/BS BV/TV |

0.56 0.52 |

0.04 0.06 (n.s.) |

|

| Cn.CaLow | MS/BS BV/TV |

0.68 0.26 |

0.007 0.37 (n.s) |

|

| Cn.CaHigh | MS/BS BV/TV |

-0.53 a -0.44 |

0.047 0.11 (n.s.) |

|

| 2yrs PTH(1-84) treatment | Cn.CaMean | MS/BS BV/TV |

-0.14 b -0.73 |

0.617 (ns.) 0.001 |

| Cn.CaPeak | MS/BS BV/TV |

-0.06 b -0.67 |

0.840 (n.s.) 0.004 |

|

| Cn.CaWidth | MS/BS BV/TV |

0.20 b 0.42 |

0.470 (n.s.) 0.11 (n.s) |

|

| Cn.CaLow | MS/BS BV/TV |

0.27 b 0.60 |

0.326 (n.s.) 0.01 |

|

| Cn.CaHigh | MS/BS BV/TV |

-0.104 b -0.74 |

0.712 (n.s.) 0.001 |

Pearson Product Moment correlation except for those variables indicated by a.

Variables did not reveal a normal distribution about the regression line with constant variance, therefore tested by Spearman rank order correlation.

The patient with relatively high MS/BS after 2yrs treatment was not representative for this treatment group and this outlier was therefore omitted for correlation analysis.

Figure 3.

BMDD outcomes for hypoparathyroid patients at baseline (white) treated for 1 year or 2 years with PTH(1-84) (dark-grey). Bars and error bars show median and IQR, respectively. Statistical comparisons to baseline (*** p<0.001, **p<0.01, * p<0.05) or to corresponding reference BMDD values (°°°p≤0.001, °°p<0.01, °p<0.05) or comparisons of 2 years versus 1 year PTH(1-84) treatment (# p≤0.05) are shown. Light-grey bars in the background indicate interquartile range of corresponding reference BMDD established previously (reference Cn.BMDD from (17), reference Ct.BMDD from (18)).

Figure 4.

Intra-individual changes of Cn.CaMean and Cn.CaWidth due to (a) 1yr-PTH(1-84) (left) or (b) 2yrs-PTH(1-84) treatment (values from the individual patients are indicated by colours and lines). These parameters are highly sensitive to treatment effects. Please note the different scales for Cn.CaWidth and Cn.CaLow.

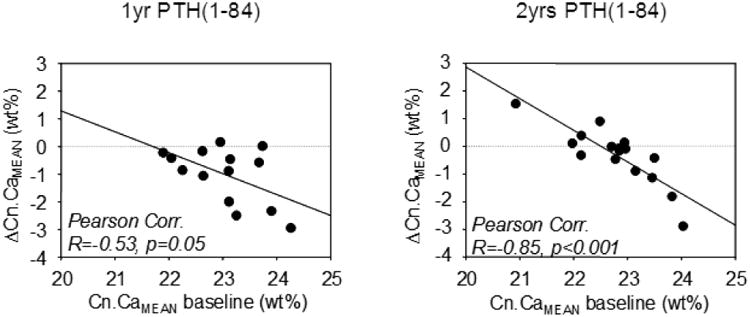

Analyses of the relationship between the intra-individual changes (differences from baseline) of the average degree of mineralization in cancellous (ΔCn.CaMean= Cn.CaMean after treatment minus Cn.CaMean at baseline) and the corresponding baseline values (Cn.CaMean) in both treatment group, revealed that the higher the baseline value of Cn.CaMean, the larger was the drop in the degree of mineralization during PTH(1-84) treatment (Fig. 4). This was observed in both treatment groups separately, however, the correlation for the 2 years treatment group was much stronger than that for the 1 year group. Moreover, the regression line indicated that those patients having a baseline CaMean value around 22.2 weight % Ca (which is the Cn.CaMean of the normative Reference cohort) did not experience any changes in Cn.CaMean by PTH(1-84).

Correlation analyses (parametric Pearson Product Moment correlation or non-parametric Spearman Rank Order correlations) between the changes (differences from baseline) of the paired Cn.BMDD outcomes versus the changes of paired cancellous histomorphometric outcomes such as MS/BS and BV/TV (obtained from a previous study (12)) revealed significant relationships with the changes in many of the Cn. BMDD parameters (Table 2 and Fig. 5) in both treatment groups. However, the correlations displayed specific differences between 1 year and 2 years PTH(1-84) treatment. Specifically, the dependency on the MS/BS for ΔCn.CaMean was remarkably strong in the 1 year group and was not statistically significant in the 2 years group (the outlier with relatively high MS/BS was not considered for this correlation), while the dependency on BV/TV was less in the 1 year and stronger in the 2 years group (see Figure 5, Table 2).

Figure 5.

Correlation of the absolute change in Cn.CaMean from baseline (ΔCn.CaMean = Cn.CaMean after treatment minus Cn.CaMean at baseline) with baseline Cn.CaMean for the 1yr-PTH(1-84) (left) and 2yrs-PTH(1-84) treatment groups (ΔCn.CaMean equals zero indicates that CaMean after treatment was similar to that at baseline).

Discussion

BMDD assessment in paired transiliac biopsy samples from hypoparathyroid patients of two treatment groups with different duration of PTH(1-84) administration revealed that patients at baseline had higher bone matrix mineralization on average than normal, which was associated with a low bone turnover status. Treatment for one year with PTH(1-84) caused a decrease in bone matrix mineralization accompanied by increasing levels of bone turnover. However, when the patients were treated for two years with PTH(1-84), the degree of mineralization was at similar levels to those at baseline.

In hypoparathyoid patients, absent PTH levels are associated with low bone turnover along with higher bone volume than normal and other microstructural skeletal abnormalities (3, 12). Our findings reveal that hypoparathyroid patients at baseline have a relatively high variation in the degree of cancellous bone matrix mineralization but group comparison to reference revealed in average higher cancellous bone matrix mineralization densities than normal, consistent with the decreased bone turnover in our study cohort. When bone turnover is low, less bone volume/area is formed with lower mineral content; bone matrix has a prolonged time for secondary mineralization, thus leading to higher levels of mineral content (19, 20). In terms of BMDD parameters, without PTH, only a lower portion of newly formed areas undergoing primary mineralization (CaLow) is detectable, while an increased percentage of highly mineralized bone areas (CaHigh) is present. Both the average degree of mineralization (CaMean) together with the peak position (CaPeak) are shifted to higher mineral concentrations. Noteworthy in particular in the context of the high variation in bone matrix mineralization in the present cohort is that children with hypoparathyroidism due to an activating mutation of the calcium sensing receptor had the opposite findings, with abnormally low mineralization densities, possibly because the calcium sensing receptor plays a role in bone mineralization kinetics (21).

Another interesting observation is that in contrast to the cancellous compartment, cortical bone did not reveal the increased degree of bone matrix mineralization in our study cohort at baseline. However, previous histomorphometric outcomes gave evidence for a larger decrease in cancellous bone turnover compared to cortical bone turnover (12), which suggests some preservation of bone turnover in the cortical compartment. Furthermore, bone structure might also play a role for matrix mineralization. In our hypoparathyroid patients, cortical structure (width and porosity) were not different to normal while cancellous bone volume was increased by increased trabecular thickness. As bone turnover is a surface-based phenomenon, larger areas in trabecular centers might become older and higher mineralized as they are shielded from bone turnover.

The administration of PTH(1-84) to the hypoparathyroid patients caused a rapid increase in bone turnover. Serum bone turnover markers (CTX, P1NP, TRAP-5b, BAP, and osteocalcin) increased significantly as early as one month after initiation of PTH(1-84) treatment (12). These markers showed that the increase peaked in months 6-12, followed by a decrease to levels still higher than baseline until month 24. In previous studies of osteoporotic patients it was shown that treatment with PTH (1-34) significantly affects bone matrix mineralization (22, 23, 24, 25, 26). Strong responses to parathyroid hormone therapy both in terms of bone turnover (27, 28) and bone matrix mineralization (29) were also observed in transiliac bone biopsy samples in osteoporotic patients with highly reduced bone turnover at baseline due to prior bisphosphonate therapy. A rapid change in bone turnover causes characteristic effects on the BMDD (30, 20). When the bone formation rate is increased, the percentage of newly formed and less mineralized bone volume/areas rises, which is accompanied by an increase in the heterogeneity of mineralization (CaWidth, the width of the BMDD) and consequently a drop of the average degree of mineralization (CaMean). In contrast, when the bone turnover rate is decreased, the opposite effects are observed, namely a decrease in CaLow, CaWidth and an increase in CaMean.

In line with the aforementioned observations, our hypoparathyroid patients revealed distinct increases in CaWidth, CaLow and a decrease in CaMean in cancellous and cortical bone after 1yr PTH(1-84). However, after 2yrs of PTH(1-84), only CaWidth was somewhat above baseline level, while none of the other aforementioned characteristic changes could be observed. There are two scenarios to explain these differential effects of PTH on BMDD with treatment duration. First, the patients in the 2yrs treatment group might have experienced generally lower or no increase in MS/BS, because this study group might have comprised numerous non-responders to PTH (1-84). However, this seems unlikely as bone formation marker increased strongly during the first year of PTH(1-84) for all the patients independent of the patients group (12). The second, more likely, scenario is that the BMDD changes after two years reflect the overall composite of changes during the two years of treatment. In the initial period, bone turnover rate was accelerated for approximately 9 months, but then decelerated during the subsequent second period. The serum bone formation marker P1NP, for example, increased approximately 4-fold during the first period which was followed by a drop to about the half of the peak value (12). Therefore, the bone turnover did not reach a steady state condition during these two years of PTH(1-84) treatment and the effects on the BMDD are expected to be an overlay of the characteristic changes, reflecting both the increased plus subsequently normalized bone turnover. This might explain why the 2yr PTH(1-84) treatment group contained a few patients who did not have a decrease in Cn.CaMean but in fact an increase in this parameter. Additionally, CaWidth, a parameter very sensitive to changes in bone turnover (30, 20), was found to be significantly reduced in two patients of the 2yr treatment group, in contrast to the increase in the remaining group. The decrease is consistent with a period of decreasing bone turnover rate.

We also observed correlations of the changes of most Cn.BMDD parameters with changes of cancellous histomorphometric parameters of bone formation (MS/BS) during treatment. This is consistent with numerous previous observations, where we also found a strong negative correlation between CaMean and MS/BS, a gold standard for bone turnover (31). However, correlation analysis revealed remarkable differences between the 1 year and 2 year treatment group. For ΔMS/BS the correlation coefficient was high for 1 year (Fig. 5) which is explained by the much greater variation in changes in MS/BS in the 1 year group compared to the 2 years treatment group (interquartile range of MS/BS changes is about 9.6-fold after 1yr PTH(1-84) compared to 2yrs PTH(1-84) treatment), while in the latter treatment group the MS/BS changes from baseline were grouped around a relatively low level. Moreover, the higher the deviation from baseline normal Cn.CaMean, the greater was the change of this parameter during treatment. This suggests that baseline bone turnover and mineralization are predictive for the treatment effect on mineralization. A relationship between baseline levels and treatment effects, although in the opposite direction, was also observed for osteoporotic patients treated with bisphosphonates (32, 33). In the latter case, the lower the baseline bone matrix mineralization was, the greater was the gain in matrix mineralization during bisphosphonate treatment. Therefore, one might hypothesize that the greater the deviation from normal bone turnover or mineralization, the greater may be the treatment effect on mineralization.

The observation of a strong negative dependency of changes in histomorpometric bone volume (ΔBV/TV) with changes in Cn. BMDD after PTH(1-84) treatment is a novel finding. These correlations might be caused by large amounts of new bone formed with PTH(1-84) treatment having only a relative short secondary mineralization period. The relatively large percentage of low mineralized bone areas (CaLow) led to the decrease in CaMean (which is the calculated mean mineralization density of the entire studied bone area). Additionally, PTH(1-84) administration did not only cause an increase in bone volume, but also an increase in bone surface as was described by the occurrence of trabecular tunneling and increased cortical porosity (12). This contrasts with the situation at baseline where the large bone volume is associated with higher bone matrix mineralization densities in cancellous bone.

The clinical consequences of our findings may relate to fracture risk in hypoparathyroidism. Fracture risk has not been found to be increased in a recent study of hypoparathyroidism (34). With PTH treatment, we observed an initially dramatic change in mineralization, perhaps reflecting a heightened state of PTH responsiveness, which became tempered during the second year. Whether fracture risk changes with PTH(1-84) treatment is still unknown, however, the change of most BMDD parameters toward normal or toward baseline levels after the end of the second year with PTH(1-84) does not suggest an additional risk due to matrix mineralization changes. Additionally, it remains unknown if the replacement therapy with the missing hormone might decrease or diminish the previoulsy reported protective effect of hypoparathyroidism against age-related bone loss (5). A further clinical consequence of our findings could relate to calcium metabolism. Requirements for supplemental calcium and vitamin D were lower at 1 year than at 2 years (11), perhaps suggesting that in the early phase of treatment the mobilization of calcium from the skeleton is greater.

Conclusion

In the PTH-deficient skeleton, cancellous bone matrix mineralization is markedly increased as compared to normal. With PTH(1-84) treatment over 1 year, increased levels of bone turnover are associated with a decrease in the degree of mineralization and an increase in the heterogeneity of mineralization. After 2 years of PTH(1-84), the degree of mineralization is similar to baseline, although the greater heterogeneity in matrix mineralization persists. These data suggest that PTH exposure to the hypoparathyroid skeleton has the greatest effects on BMDD early in treatment. Further studies are necessary to explore to what extent these BMDD changes affect skeletal strength and whether other bone material characteristics are also affected by treatment in hypoparathyroidism.

Figure 6.

Correlation of the absolute changes (differences to baseline) in Cn.CaMean, and Cn.CaWidth with the changes in histomorphometric cancellous mineralizing surface (MS/BS). The regression lines are shown for both treatment groups (1yr-PTH(1-84) triangular symbols, 2yrs-PTH(1-84) circular symbols) separately. Correlation coefficients and corresponding p-value are shown in Table 2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank D. Gabriel, P. Keplinger, S. Lueger and P. Messmer for technical assistance (sample preparation and qBEI measurements) at the Bone Material Laboratory of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute of Osteology, Vienna, Austria. This work was supported by the AUVA (Austrian Social Insurance for Occupational Risk) and the WGKK (Social Health Insurance Vienna) (BMM, PR, KK), and the NIH grant DK069350 (MRR). The authors acknowledge NPS Pharmaceuticals for supplying the PTH (1-84).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: BMM, PR, KK, HZ and MRR state that they have no conflicts of interest. DWD and JPB state that they have served as consultants to NPS Pharmaceuticals.

Authors' roles: All authors made substantial contributions to either the conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data, participated in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

References

- 1.Sikjaer T, Rolighed L, Hess A, Fuglsang-Frederiksen A, Mosekilde L, Rejnmark L. Effects of PTH(1-84) therapy on muscle function and quality of life in hypoparathyroidism: results from a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2014 Jun;25(6):1717–26. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2677-6. Epub 2014 Apr 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cusano NE, Rubin MR, McMahon DJ, Irani D, Anderson L, Levy E, Bilezikian JP. PTH(1-84) Is Associated with Improved Quality of Life in Hypoparathyroidism Through 5 Years of Therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun 30; doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2267. jc20142267. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin MR, Dempster DW, Kohler T, Stauber M, Zhou H, Shane E, Nickolas T, Stein E, Sliney J, Jr, Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP, Müller R. Three dimensional cancellous bone structure in hypoparathyroidism. Bone. 2010 Jan;46(1):190–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.09.020. Epub 2009 Sep 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langdahl BL, Mortensen L, Vesterby A, Eriksen EF, Charles P. Bone histomorphometry in hypoparathyroid patients treated with vitamin D. Bone. 1996;18(2):103–8. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00443-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeman E, Wahner HW, Offord KP, Kumar R, Johnson WJ, Riggs BL. Differential effects of endocrine dysfunction on the axial and the appendicular skeleton. J Clin Invest. 1982 Jun;69(6):1302–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI110570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke BL. Bone disease in hypoparathyroidism. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2014 Jul;58(5):545–52. doi: 10.1590/0004-2730000003399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujiyama K, Kiriyama T, Ito M, Nakata K, Yamashita S, Yokoyama N, Nagataki S. Attenuation of postmenopausal high turnover bone loss in patients with hypoparathyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995 Jul;80(7):2135–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.7.7608266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winer KK, Ko CW, Reynolds JC, Dowdy K, Keil M, Peterson D, Gerber LH, McGarvey C, Cutler GB., Jr Long-term treatment of hypoparathyroidism: a randomized controlled study comparing parathyroid hormone-(1-34) versus calcitriol and calcium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003 Sep;88(9):4214–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winer KK, Fulton KA, Albert PS, Cutler GB., Jr Effects of pump versus twice-daily injection delivery of synthetic parathyroid hormone 1-34 in children with severe congenital hypoparathyroidism. J Pediatr. 2014 Sep;165(3):556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.04.060. Epub 2014 Jun 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rejnmark L, Underbjerg L, Sikjaer T. Therapy of hypoparathyroidism by replacement with parathyroid hormone. Scientifica (Cairo) 2014;2014:765629. doi: 10.1155/2014/765629. Epub 2014 Jul 1 Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubin MR, Sliney J, Jr, McMahon DJ, Silverberg SJ, Bilezikian JP. Therapy of hypoparathyroidism with intact parathyroid hormone. Osteoporos Int. 2010 Nov;21(11):1927–34. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1149-x. Epub 2010 Jan 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubin MR, Dempster DW, Sliney J, Jr, Zhou H, Nickolas TL, Stein EM, Dworakowski E, Dellabadia M, Ives R, McMahon DJ, Zhang C, Silverberg SJ, Shane E, Cremers S, Bilezikian JP. PTH(1-84) administration reverses abnormal bone-remodeling dynamics and structure in hypoparathyroidism. J Bone Miner Res. 2011 Nov;26(11):2727–36. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sikjaer T, Rejnmark L, Thomsen JS, Tietze A, Brüel A, Andersen G, Mosekilde L. Changes in 3-dimensional bone structure indices in hypoparathyroid patients treated with PTH(1-84): a randomized controlled study. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 Apr;27(4):781–8. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gafni RI, Brahim JS, Andreopoulou P, Bhattacharyya N, Kelly MH, Brillante BA, Reynolds JC, Zhou H, Dempster DW, Collins MT. Daily parathyroid hormone 1-34 replacement therapy for hypoparathyroidism induces marked changes in bone turnover and structure. J Bone Miner Res. 2012 Aug;27(8):1811–20. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roschger P, Fratzl P, Eschberger J, Klaushofer K. Validation of quantitative backscattered electron imaging for the measurement of mineral density distribution in human bone biopsies. Bone. 1998;23:319–326. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roschger P, Paschalis EP, Fratzl P, Klaushofer K. Bone mineralization density distribution in health and disease. Bone. 2008;42:456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roschger P, Gupta HS, Berzlanovich A, Ittner G, Dempster DW, Fratzl P, Cosman F, Parisien M, Lindsay R, Nieves JW, Klaushofer K. Constant mineralization density distribution in cancellous human bone. Bone. 2003;32:316–323. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00973-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misof BM, Dempster DW, Zhou H, Roschger P, Fratzl-Zelman N, Fratzl P, Silverberg SJ, Shane E, Cohen A, Stein E, Nickolas TL, Recker RR, Lappe J, Bilezikian JP, Klaushofer K. Relationship of Bone Mineralization Density Distribution (BMDD) in Cortical and Cancellous Bone Within the Iliac Crest of Healthy Premenopausal Women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;95(4):332–9. doi: 10.1007/s00223-014-9901-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boivin G, Meunier PJ. The degree of mineralization of bone tissue measured by computerized quantitative contact microradiography. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;70:503–511. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-2048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roschger P, Misof B, Paschalis E, Fratzl P, Klaushofer K. Changes in the degree of mineralization with osteoporosis and its treatment. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2014 Sep;12(3):338–50. doi: 10.1007/s11914-014-0218-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theman TA, Collins MT, Dempster DW, Zhou H, Reynolds JC, Brahim JS, Roschger P, Klaushofer K, Winer KK. PTH(1-34) replacement therapy in a child with hypoparathyroidism caused by a sporadic calcium receptor mutation. J Bone Miner Res. 2009 May;24(5):964–73. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Misof BM, Roschger P, Cosman R, Kurland ES, Tesch W, Messmer P, Dempster DW, Nieves J, Shane E, Fratzl P, Klaushofer K, Bilezikian J, Lindsay R. Effects of intermittent parathyroid hormone administration on bone mineralization density distribution in iliac crest biopsies from patients with osteoporosis: a paired study before and after treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1150–1156. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Misof BM, Paschalis EP, Blouin S, Fratzl-Zelman N, Klaushofer K, Roschger P. Effects of 1 year of daily teriparatide treatment on iliacal bone mineralization density distribution (BMDD) in postmenopausal osteoporotic women previously treated with alendronate or risedronate. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Nov;25(11):2297–303. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arlot M, Meunier PJ, Boivin G, Haddock L, Tamayo J, Correa-Rotter R, Jasqui S, Donley DW, Dalsky GP, Martin JS, Eriksen EF. Differential effects of teriparatide and alendronate on bone remodeling in postmenopausal women assessed by histomorphometric parameters. J Bone Miner Res. 2005 Jul;20(7):1244–53. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paschalis EP, Glass EV, Donley DW, Eriksen EF. Bone mineral and collagen quality in iliac crest biopsies of patients given teriparatide: new results from the fracture prevention trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Aug;90(8):4644–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2489. Epub 2005 May 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jobke B, Muche B, Burghardt AJ, Semler J, Link TM, Majumdar S. Teriparatide in bisphosphonate-resistant osteoporosis: microarchitectural changes and clinical results after 6 and 18 months. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011 Aug;89(2):130–9. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9500-6. Epub 2011 May 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stepan JJ, Burr DB, Li J, Ma YL, Petto H, Sipos A, Dobnig H, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Michalská D, Pavo I. Histomorphometric changes by teriparatide in alendronate-pretreated women with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2010 Dec;21(12):2027–36. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma YL, Zeng QQ, Chiang AY, Burr D, Li J, Dobnig H, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Michalská D, Marin F, Pavo I, Stepan JJ. Effects of teriparatide on cortical histomorphometric variables in postmenopausal women with or without prior alendronate treatment. Bone. 2014 Feb;59:139–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misof BM, Paschalis EP, Blouin S, Fratzl-Zelman N, Klaushofer K, Roschger P. Effects of 1 year of daily teriparatide treatment on iliacal bone mineralization density distribution (BMDD) in postmenopausal osteoporotic women previously treated with alendronate or risedronate. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Nov;25(11):2297–303. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruffoni D, Fratzl P, Roschger P, Phipps R, Klaushofer K, Weinkamer R. Effect of temporal changes in bone turnover on the bone mineralization density distribution: a computer simulation study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 Dec;23(12):1905–14. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roschger P, Dempster DW, Zhou H, Paschalis EP, Silverberg SJ, Shane E, Bilezikian JP, Klaushofer K. New observations on bone quality in mild primary hyperparathyroidism as determined by quantitative backscattered electron imaging. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:717–723. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fratzl P, Roschger P, Fratzl-Zelman N, Paschalis EP, Phipps R, Klaushofer K. Evidence that treatment with risedronate in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis affects bone mineralization and bone volume. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007;81:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misof BM, Patsch JM, Roschger P, Muschitz C, Gamsjaeger S, Paschalis EP, Prokop E, Klaushofer K, Pietschmann P, Resch H. Intravenous treatment with ibandronate normalizes bone matrix mineralization and reduces cortical porosity after two years in male osteoporosis: a paired biopsy study. J Bone Miner Res. 2014 Feb;29(2):440–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Underbjerg L, Sikjaer T, Mosekilde L, Rejnmark L. Postsurgical hypoparathyroidism--risk of fractures, psychiatric diseases, cancer, cataract, and infections. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:2504–10. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]