Preface

Synaptic plasticity is a mechanism proposed to underlie learning and memory. The complexity of the interactions between ion channels, enzymes, and genes involved in synaptic plasticity impedes a deep understanding of this phenomenon. Computer modeling is an approach to investigate the information processing that is performed by signaling pathways underlying synaptic plasticity. In the past few years, new software developments that blend computational neuroscience techniques with systems biology techniques have allowed large-scale, quantitative modeling of synaptic plasticity in neurons. We highlight significant advancements produced by these modeling efforts and introduce promising approaches that utilize advancements in live cell imaging.

Introduction

Neurons have an ability to respond differentially to specific temporal and spatial patterns of inputs. This response specificity is not programmed into neurons; rather it develops as the animal interacts with the environment and thus is called information storage or memory storage. Because a neuron’s response properties are changed through plasticity of both synapses and ion channels, this plasticity is proposed to underlie learning and memory. Consequently, to understand how neurons store information we need to understand how spatio-temporal patterns of synaptic input, combined with post-synaptic neuronal activity, produce neuronal plasticity and how such plasticity in turn changes neuronal activity patterns. Current research has revealed that a large number of molecules and complex interactions between them underlie plasticity1, 2. Therefore, simple conceptual models are no longer sufficient to adequately explain the molecular processes underlying neuronal plasticity. Instead, the role of dynamics and complicated, non-linear molecule interactions require quantitative computational models for in-depth understanding.

Two aspects of neuronal plasticity are important for information processing: plasticity of intrinsic excitability3, which is the change in ion channel properties; and synaptic plasticity, which is the change in the strength of synapses between two neurons. Though more is known about the signaling pathways underlying synaptic plasticity, many of the same pathways are also responsible for plasticity of intrinsic excitability, and the modeling approaches presented in this Review could be applied to intrinsic excitability also.

Two crucial technological advancements recently have accelerated the development of signaling pathway models. One is live cell imaging, which provides essential constraints on kinetics (rate constants) and molecular spatial organization - information on both of which is required for addressing aspects of information processing such as synaptic specificity and spatio-temporal pattern discrimination. The second advancement is the accelerating improvements of computer hardware and architecture, which is crucial owing to the temporal and spatial scale of synaptic plasticity models. Simulating large spatial structures for long durations with high resolution requires trillions of calculations

In this Review, we first summarize our current understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying synaptic plasticity of glutamatergic synapses — not only to demonstrate their complexity and the consequent need for integrative and dynamical techniques to better understand these mechanisms, but also to provide a framework for computational models of signaling pathways. In the second section, we explain some computational approaches used in systems biology that are of particular relevance to modeling synaptic plasticity, and illustrate how these computational approaches have made significant discoveries and contributions in this field. In the third section, we review some key computational models of molecular mechanisms underlying synaptic plasticity, representing the diversity of simulation approaches, brain regions, molecular pathways and emergent properties. Importantly, the models we describe were selected to highlight discoveries from simulations that were not known from experiments; some of these model discoveries were subsequently confirmed experimentally.

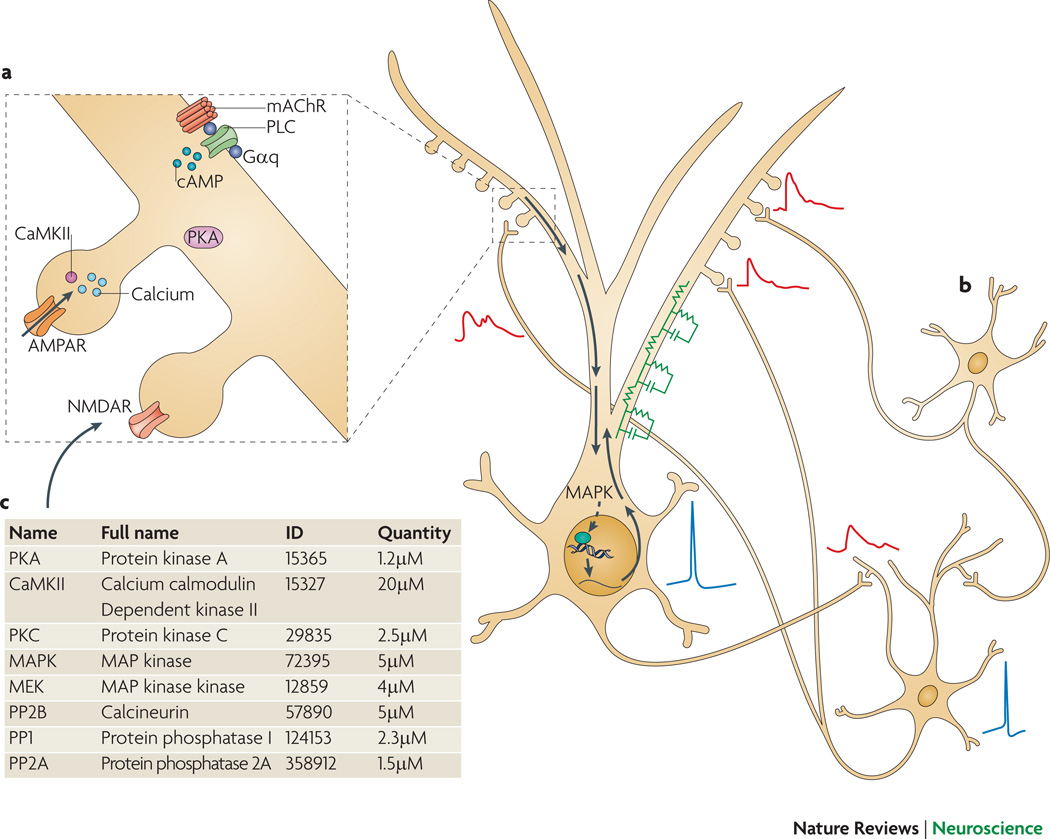

Molecular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity

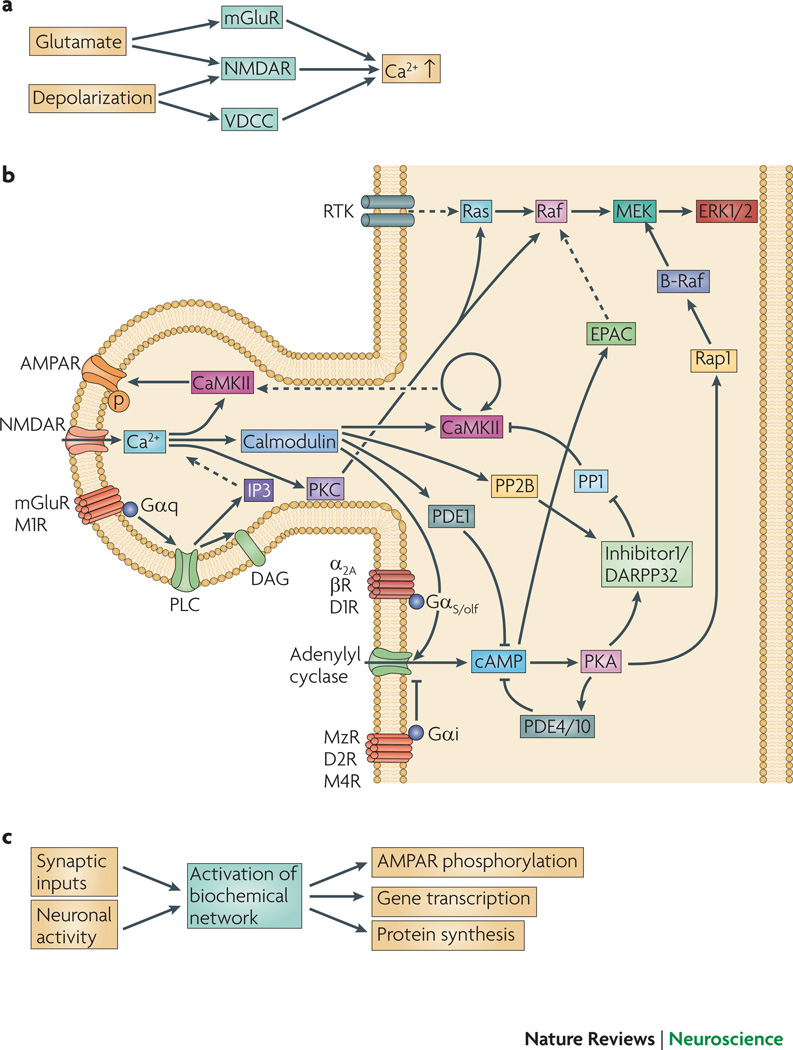

The specific types of neuronal and synaptic activity that are required for induction of long-term potentiation (LTP) or long-term depression (LTD) are diverse, and depend on the brain region and cell type. Excellent reviews of these different forms of synaptic plasticity are found elsewhere4, 5. In general, the two crucial features of most induction protocols at excitatory synapses are pre-synaptic release of glutamate and post-synaptic depolarization4 which lead to an elevation of intracellular calcium concentration in the postsynaptic cell through several mechanisms (Figure 1A).

Display 1: Figure 1. Signaling pathways underlying synaptic plasticity.

A. Presynaptic glutamate release and depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron lead to calcium elevation in the postsynaptic cell. Glutamate is required for activation of NMDA receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors, and depolarization is required for activation of NMDA receptors98 and voltage-dependent calcium channels99. The particular mechanism employed depends on the cell type.

B. Signaling pathways leading to kinase activation and AMPAR phosphorylation. Only a subset of the known pathways is illustrated, and not all pathways are involved in all neurons. Calcium activates CaMKII, which phosphoryolates the AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit, leading to increased numbers of AMPA receptors. CaMKII can be persistently activated by autophosphorylation100, 101, which occurs when two adjacent subunits are bound to calcium-calmodulin. This persistently active form of CaMKII is most strongly implicated in hippocampal LTP. Dopamine (D1) and β-adrenergic receptors102, 103, coupled to GS or Golf, contribute to LTP by activating adenylyl cyclase, while other dopamine (D2) receptors and muscarinic acetylcholine (M2, M4) receptors inhibit adenylyl cyclase. The cAMP produced by adenylyl cyclase activates PKA which subsequently phosphorylates AMPA receptor GluR1 subunits and either DARPP32 (dopamine and cAMP regulated phosphoprotein of 32 kDa) or inhibitor-1104, 105, which decrease phosphatase activity to allow persistence or enhancement of phosphorylation of AMPA receptors. Some types of muscarinic acetylcholine (M1) receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors are coupled to phospholipase C (PLC), which produces diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol triphosphate. Typical forms of PKC are activated by binding to both calcium and DAG. ERK is activated by a pathway involving tyrosine kinase receptors via the Ras-Raf-MEK pathway, and is necessary for the gene transcription and protein translation that underlies persistent forms of synaptic plasticity. In addition, ERK can be indirectly activated by PKC, EPAC, calcium and PKA.

C. For late-phase LTP and memory storage, a combination of synaptic inputs and neuronal activity leads to AMPA receptor phosphorylation, gene transcription, and protein translation.

The elevation in postsynaptic calcium concentration, crucial for induction of both LTP and LTD6, 7, leads to activation of many molecule species implicated in synaptic plasticity (Figure 1B). In some systems the magnitude of the calcium elevation predicts whether an induction paradigm will produce potentiation or depression: a large calcium elevation produces potentiation, whereas a small calcium elevation produces depression8, 9. Nonetheless, calcium concentration by itself is not always sufficient to predict the direction of plasticity10, 11. In some cell types the source of calcium influx influences whether LTD or LTP develops; for example, LTD requires activation of either mGluR or L-type calcium channels while LTP is NMDA dependent5, 12. The non-linear interactions between different sources of calcium and its multiple target molecules impede predicting the consequences of neural activity without using quantitative dynamical models.

Several protein kinases and phosphatases, activated through transmembrane receptors, are implicated in either the induction or maintenance of synaptic plasticity (Figure 1B). Induction includes events during the stimulation protocol leading to plasticity, whereas maintenance refers to events after plasticity has been induced and is blocked by application of drugs tens of minutes after induction. CaMKII, activated by calcium-bound calmodulin, is required for hippocampal and neocortical LTP. Protein kinase A (PKA) is required for LTP induction in the striatum, and for induction of a long-lasting form of NMDA-dependent LTP in the hippocampus, known as late-phase LTP13. Protein kinase C (PKC) is required for induction of LTD in the cerebellum and for induction of mGluR-dependent LTP in the hippocampus5. In addition, atypical forms of PKC, such as PKMζ, while not required for induction, have a role in the maintenance of LTP, at least in the hippocampus14, 15. Another kinase that is implicated in forms of synaptic plasticity that require transcription and translation is extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK), a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family16, 17. Inhibition of ERK impairs some forms of LTP18; conversely, ERK is elevated following some types of LTP.

Myriad experiments have elucidated the signaling pathways leading to, and neuromodulators that influence, kinase activation, but the interactions of these multiple pathways at multiple points are non-linear and therefore difficult to comprehend. For example, calcium-calmodulin activates CaMKII, but in the hippocampus it also activates adenylyl cyclase types 1 and 8, leading to production of cAMP and it activates phosphodiesterase type 1B, which degrades cAMP. Computational modeling of signaling pathways investigates these complex interactions and predicts important molecular mechanisms, which can guide experimentalists to the most valuable experiments.

Computational neuroscience

Computational neuroscience has made tremendous contributions to understanding the function of neurons (Box 1), with an emphasis on electrical activity. Well-established methods for modeling ion channels and neuron morphology permit simulation of the activity of identified ion channels, neuron morphology and, more recently, signaling pathways. Such models make explicit the assumptions about ion channel and reaction kinetics that are implicit in conceptual models. In general, these models address questions such as whether the known kinetics support the input-output relations that are predicted by conceptual models, and whether ion channels or signaling pathways that are not included in conceptual models (but that are present in the tissue) are crucial.

Display 6: Box 1. Brief history of computational neuroscience.

One of the earliest and best known discoveries in computational neuroscience was the Hodgkin-Huxley model of the squid action potential106. Hodgkin and Huxley developed equations to describe the voltage clamp currents underlying the action potential. When these equations were simulated in current clamp mode, they indeed reproduced the action potential. The computational aspect of this study made two important contributions. First, it revealed that the sodium and potassium currents were sufficient to generate the action potential - the simulation showed that no additional current was needed to explain characteristics of action potentials, such as threshold, refractory period, or action potential following release from hyperpolarization (known as anode-break). Second, the gating mechanisms predicted by the equation were subsequently confirmed experimentally. Although single channel recordings demonstrate that Markov kinetic models better describe channel mechanisms, nonetheless, Hodgkin-Huxley’s formulation provides an efficient and parsimonious explanation for many aspects of ionic channels and their contributions to neuronal activity.

The second major advance in computational neuroscience was application and extension of the cable equation to dendrites107. Rall was the first to introduce a spatial dimension to neuronal signal processing, and demonstrated that the neuronal membrane exhibits properties of a low pass filter due to parallel resistive and capacitive characteristics. Parsimoniously, these same membrane properties cause attenuation and temporal delay of synaptic potentials that are passively propagated along a dendrite. When synapses are represented as changes in membrane conductance, the cable equation can explain spatial and temporal summation of synaptic inputs. Although many dendrites have voltage-dependent ion channels, multi-compartmental resistive-capacitive models of neuronal morphology is the foundation upon which more complicated neuronal models are built. These models are used to test the role of particular ion channels or morphology in neuronal activity.

Synaptic plasticity has been more difficult to capture in computational models. Unlike models for ion channels and morphology, models of synaptic function do not simultaneously describe molecular mechanisms and accurately capture the experimental results. There are two types of synaptic plasticity models. First, phenomenological models19–21 accurately describe the relation between in vitro neural activity and resulting synaptic plasticity. While these models are valuable for investigating neural network level functions as a result of synaptic plasticity, they do not address mechanisms underlying plasticity. Second, more mechanistic models typically describe the role of calcium in synaptic plasticity by blending traditional compartmental models describing electrical activity22–25 with equations describing calcium dynamics. These models have shown that the amplitude of calcium elevation depends on the frequency of synaptic stimulation, owing to the voltage-dependence of the NMDA receptor, but they seldom include the kinases directly implicated in plasticity. The scarcity of complete models of synaptic plasticity reflects the complexity of underlying mechanisms. Thus, a challenging and important future goal is to apply a new, systems-level approach to achieve a deep understanding of information processing and memory storage in neurons. Though this is exceedingly difficult due to lack of information on quantity and subcellular localization of critical enzymes, modeling facilitates a deep understanding of the multiple, interacting, non-linear processes in cells because of its synthetic and integrative approach.

Approaches in systems biology

Understanding a biological system in terms of function, regulation, adaptation and robustness requires characterization of both the individual components and the dynamic interactions between them over multiple temporal and spatial scales. Systems biology achieves this level of understanding by combining computational modeling and theoretical analysis with large-scale experimental investigation. Using this combined approach, fundamental questions, such as how complex cellular signaling networks are functionally organized, have been successfully addressed26. As the signaling cascades underlying synaptic plasticity are a subset of those studied by systems biologists, the following approaches are applicable to computational studies of synaptic plasticity.

Graph theory and network topology

One approach in systems biology employs network or graph theory27–29 to discover and predict the dependencies between genes, proteins, etc. Experimental techniques in combination with powerful computational and statistical methods allow the identification of DNA sequences, proteins, and lipids, and whether such components can physically interact (or are associated in time or space)30–33. Graph theory takes advantage of, and indeed is required to make sense of, the data from the recently developed high through-put methods forming a basis for fields such as genomics, proteomics and connectomics. When graph theory is applied to biochemical networks, the nodes in the network represent molecular species and the edges represent the interactions between them. The foundational rationale is that information about the topology that is inherent in those data can lead to the discovery of principles of network function and malfunction, and that predictions can be made without knowledge of the systems dynamics. One fundamental discovery is that metabolic networks have properties of scale-free or small world networks34. Unlike either randomly connected or highly connected networks, the path length between any two nodes is small, and the number of edges exhibits a power law. These properties imply that very few proteins are highly connected, but many proteins have only a few interactions. The significance of these highly connected proteins has been demonstrated experimentally, in that they are conserved, and more likely to be essential than proteins with only a small number of connections27. Graph theory has identified common mechanisms involved in neurodegenerative diseases35 and has predicted novel pathways, critical molecules, and the overall network design logic in signaling networks controlling e.g. differentiation of the nervous system36. Alterations in protein interaction networks can even be used to predict and follow the clinical outcome in cancer treatments37. In systems biology of the brain, the phosphoprotein network of the synapse, consisting of more than 1500 proteins, has been suggested as a starting point for linking molecules to behaviour2, 38. The synaptic interaction networks form the general basis for the evolutionary origin of behaviour and cognition39.

Network motifs and network function

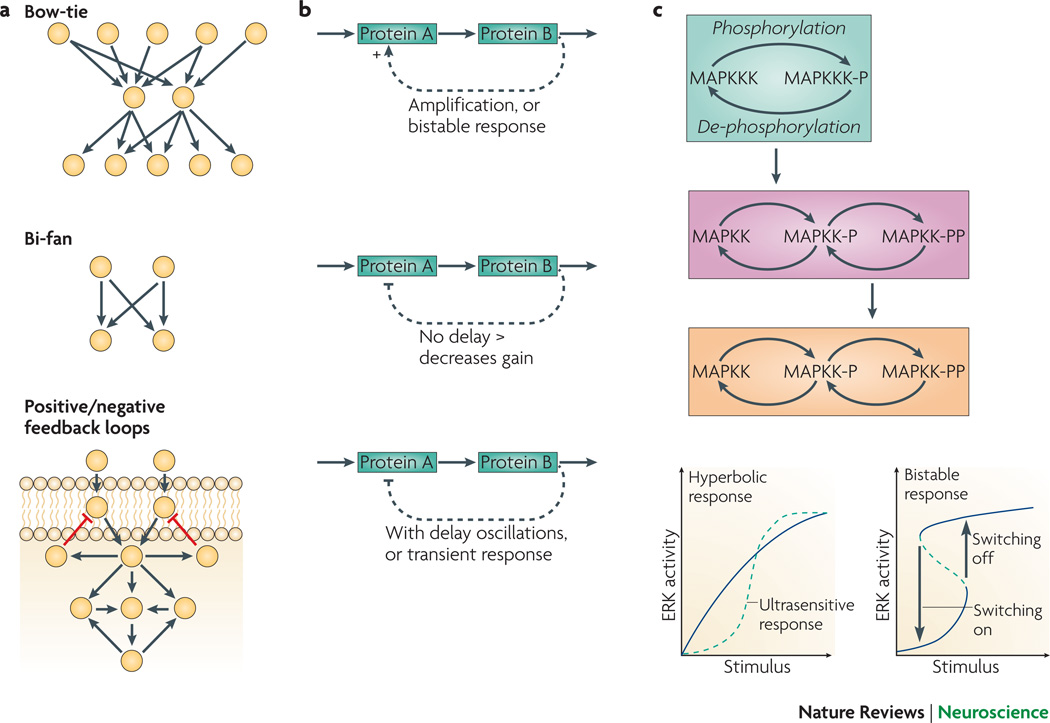

Several attempts have been made to identify functional network modules from network connectivity. If larger networks are composed of smaller modules, then the computational function of the larger network may be understood from the computational function of the smaller modules40. Indeed, small recurring structural modules, denoted “network motifs”, are commonly found41. Feedforward and feedback loops are examples of such motifs29(Fig 2A).

Display 2: Figure 2.

A. Examples of common structures found in cell signaling networks that have been identified using graph theory29. A1. A “Bow-tie” structure: signals from many receptors converge onto a few cytosolic targets which in turn regulate many transcription factors; A2. The “bifan” motif : two input nodes directly cross-regulate target nodes; A3. Negative feedback loops that include receptors are more often observed close to the membrane, and positive feedback loops (often highly nested) are more commonly found a few steps downstream from receptors. B. Dynamics in minimal pathway components in cell signaling networks. B1. Positive feedback loop. The feedback results in a larger response than if no feedback were present. The interaction between voltage and L type or non-inactivating inward calcium channels show this type of positive feedback. In some cases positive feedback might result in bistability; B2. Negative feedback loop with no (or in practical cases very little) delay. The feedback results in a smaller response than if no feedback were present. Non-inactivating outward K channels exhibit negative feedback; B3. Negative feedback loop with delay. The delayed feedback reduces the response after an initial transient response. Oscillations can occur in response to sustained input. C. A generic MAPK pathway. C1. A single phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle is circled in green. The MAPK cascade consists of three layers of such cycles, and the two lower layers have dual phosphorylation sites. C2. Phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycles can in certain conditions show “ultrasensitivity” and behave as threshold devices. The layered cascade, with dual phosphorylation sites, can sustain bistability as well. Bistability requires hysterisis: the response to an increasing input differs from the response to a decreasing input. In contrast, ultrasensitivity exhibits a similar steep increase in output with small changes in input, but the threshold is identical for increasing and decreasing inputs.

One limitation in studying motifs identified from network connectivity is the inability to capture dynamics, e.g. the time dependent variation in membrane potential or phosphorylation state, that are produced by synaptic inputs and action potentials, which depend on kinetics: e.g. the rate of reactions. Knowing this kinetic information is essential for determining the input-output relationship of motifs in various systems42. For example, consider a positive feedback loop, whereby protein A activates protein B, which further activates protein A. If the loop behaves as a bistable switch (Fig 2B,C), then a sufficiently high input can change the output from the low activation state to the high activation state. Thus, activation is maintained even after the original input is reduced. However, if the kinetics are too slow, the loop will not transition from one state to another, and only a transient increase in output is achieved before the system decays to the previous state. Dynamical behavior of negative feedback pathways (Fig 2B) ― whereby protein A activates protein B, which inhibits protein A in one or several intermediate steps ― also depends on kinetics. If the feedback loop is fast, i.e. with minimal delay, the feedback loop will produce a general decrease in overall response. If a significant delay is incorporated into the feedback loop, or if the loop consists of several intermediate steps, a transient response is seen or oscillations may occur43, 44. These examples illustrate the need for models of dynamical activity, which requires quantitative data to constrain the kinetics of the interactions to be modeled. Here, imaging (Box 2) reveals the dynamics of critical network components, even at the level of the single cell45.

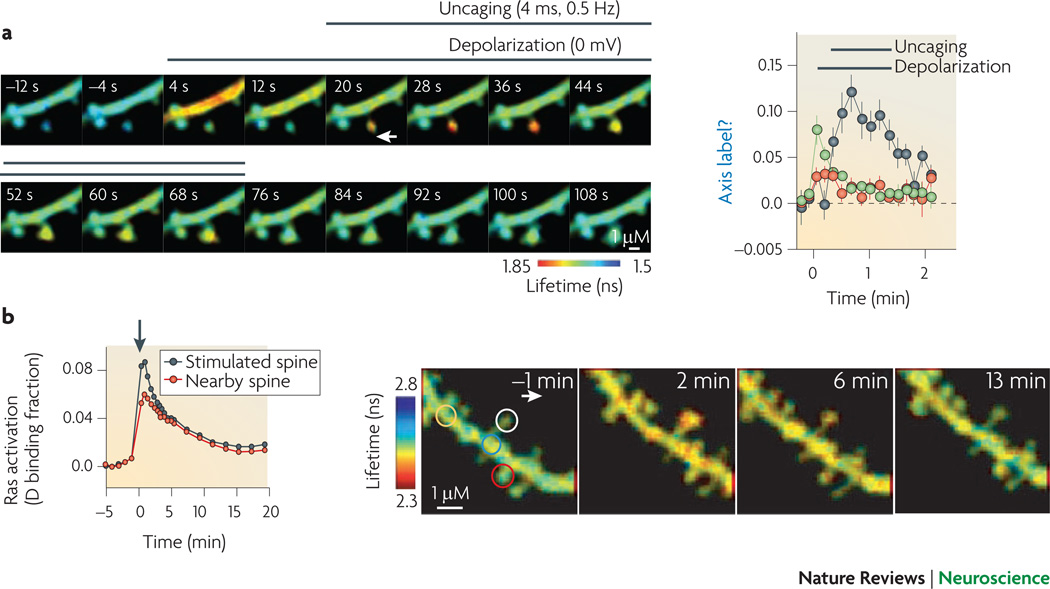

Display 7: Box 2.

New techniques in imaging provides high resolution data both in the spatial and temporal domains to improve the reliability of model development. Several techniques have been developed using the green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequorea Victoria108. The GFP molecule has been modified to a variety of colors which are excited by and emit at different wavelengths. FRET109 (fluorescence resonance energy transfer) is a technique in which the light emitted by cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) excites a yellow fluorescent protein that functions as an acceptor (YFP) when the two are in close proximity. CFP and YFP are attached either to two parts of a molecule (unimolecular FRET sensor) which changes conformation on ligand binding, or to two different molecules that interact (bimolecular FRET sensor). The ratio of cyan to yellow emission measures the extent of ligand binding or interaction as a function of space and time). In fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) interactions are measured by comparing the time (i.e. lifetime) until one isolated fluorophore has emitted and returned to the ground states, and the shorter time of the fluorescent event in the presence of an acceptor molecule in the environment. Fluorescence recovery after bleaching (FRAP) provides information on the rate of diffusion, and the fraction of immobile versus mobile molecules. The GFP molecules in a small region are bleached, and the recovery results from unbleached molecules diffusing back into the region. Newer techniques are able to measure multiple molecules simultaneously110.

These imaging techniques allow for visualization of relatively fast events, such as calcium, cAMP or kinase activity transients. The figure illustrates FLIM imaging of hippocampal neurons following LTP induction protocols using glutamate uncaging. It shows that active CaMKII remains in an individually activated spine111, while in contrast, calcium dependent Ras activity diffuses a short distance to neighboring spines112. These imaging data from living cells constrain biochemical rate constants, and reveal the spatial extent of molecule activation, which can be correlated with measures of synaptic plasticity112. Reprinted with permission.

Dynamical modeling approaches

Dynamic modeling builds on the information about networks provided by graph theory, but evaluates time dependent changes in activities of proteins and other molecules. This approach is used to test hypotheses or explore ideas “in computo” that are currently difficult or impossible to investigate experimentally. The simplest type of dynamical model, which does not require specific kinetic rate constants, is perhaps the boolean logic network in which quantities can have only two discrete values: present and absent. Logical operations (e.g. if protein A and protein B are present) coupled with explicit time delays (e.g. protein C is present later) can explain phenomena such as gene activation patterns46. A more mechanistic approach to understanding dynamics in both gene-, metabolic- and signaling networks is to represent biochemical reactions using algebraic and ordinary differential equations43, 47. Many of the parameters in such equations represent biochemically measurable values, such as enzyme turnover rates, affinities, or on- and off- rates. Other parameters are slightly more abstract, representing an observed modulatory effect on a reaction. In both cases, many of the parameters are constrained by experimental measurements of kinetic rate constants48.

The family of MAPK pathways provides examples of discoveries gained using dynamic modeling approaches. The MAPK cascade consists of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation cycles (Fig 2C). Multiple layers of phospho- and dephospho cycles, with multi-site phosphorylations, amplify input signals significantly, and can produce “ultrasensitivity”, such that a small change in input near a threshold value49 is translated into a sharp change in the output. Depending on the rate constants of the reactions and the relative abundance of enzyme and substrate, the MAPK cascade can produce bistability50. Alternatively, the MAPK cascade can show oscillations49 or respond in a graded manner. Dynamical modeling has revealed that the amplitude or temporal properties of an input to the MAPK pathway control which of a multitude of MAPK target molecules is activated51, 52.

Dynamical Stochastic Approaches

A common, but incorrect assumption in modeling is that the number of molecules is large enough to be represented as concentration. Many subcellular compartments are small, so that they can contain only limited numbers of molecules, and in larger compartments the concentration of a molecule can simply be low. For example, few calcium molecules reside in a spine during resting conditions owing to the small volume, a variable number of calcium molecules enter a spine during stimulation due to stochastic release of transmitter and gating of membrane channels, and transcription factors in the nucleus are few in number. In all these cases, stochastic fluctuation in molecule numbers adds variability or can change the outcome of signaling pathways. The consequence is that stochastic effects need to be taken into account when modeling a system.

Stochastic variability, or noise, can produce erroneous activity and obliterates strong notions of stability (and bistability). Many methods for stochastic modeling of systems of biochemical reactions are based on the exact stochastic simulation algorithm53. All of these methods, including variations which improve its computational efficiency, ignore the dependence of reactions on molecule collisions because molecules are represented as points. Other methods for stochastic reactions consider molecule geometry and charge, but these molecular dynamics simulations typically investigate single bimolecular reactions, and are rarely applied to large systems of reactions54. Stochastic simulations have revealed that signaling pathways such as positive feedback loops, which produce bistable switches when modeled deterministically, are no longer bistable. If the dynamics of the switch are fast, noise activates the switch too easily. Alternatively, dynamics of the switch may be adjusted to be robust against noise, with the consequence that the switch is not sufficiently sensitive to the signal. Modeling suggests that one solution used by biology to reduce the effect of noise is the commonly observed motif of coupled fast and slow feedback loops, which simultaneously allows for high sensitivity to signal and reduces sensitivity to noise ― both internal noise due to low numbers of molecules and external noise that is present in the input55, 56.

Dynamical Spatial Approaches

Another simplifying, but false, assumption in modeling is that the system is well mixed, i.e., the molecules are equally distributed throughout the system so that there are no subcompartments. In reality, a signaling cascade might be activated at the cell membrane where the receptors are located, and then cause activation of targets in the cell nucleus (e.g. the MAPK pathway, where MAPKKK is phosphorylated in the membrane region and MAPK can have a nuclear target). Moreover, the kinases and phosphatases that control the activity of a particular enzyme might be located in different subcellular compartments, such as the membrane versus the cytosol or in a spine versus the dendrite (Fig 3). Diffusion is important in controlling dynamics of molecular interactions between such subcompartments, for example when the rate of diffusion is significantly slower than the rate of the reactions within subcompartments. Slow diffusion coupled with localization or anchoring of proteins can result in microdomains of second messengers (Fig 3). Such reaction-diffusion problems can be modeled either deterministically or stochastically57. In deterministic methods molecule concentrations are calculated as a function of space and time using partial differential equations. In stochastic methods molecule numbers are calculated as a function of space and time using Monte Carlo methods. These latter methods can be subdivided into methods representing individual particles, each of which can reside at an arbitrary location58, and those discretizing space into individual voxels59. Individual particle methods have the advantage that they take into account the size of the particles, which allows simulation of effects such as molecular crowding60. The disadvantage of individual particle methods is that simulation of large numbers of molecules is still too expensive computationally. Some of the voxel-based methods allow multiple molecules to reside in each voxel (this is also known as the mesoscopic approach61, 62) and keep track of numbers of each molecule species (or number of molecules in each phosphorylation state). The advantage of these mesoscopic approaches is the ability to simulate larger volumes and numbers of molecules; the disadvantage of these methods is that they cannot simulate particle crowding or the role of molecule location within the PSD. For all these methods, a major challenge is to model reactions involving multi-subunit molecules with numerous phosphorylation states.

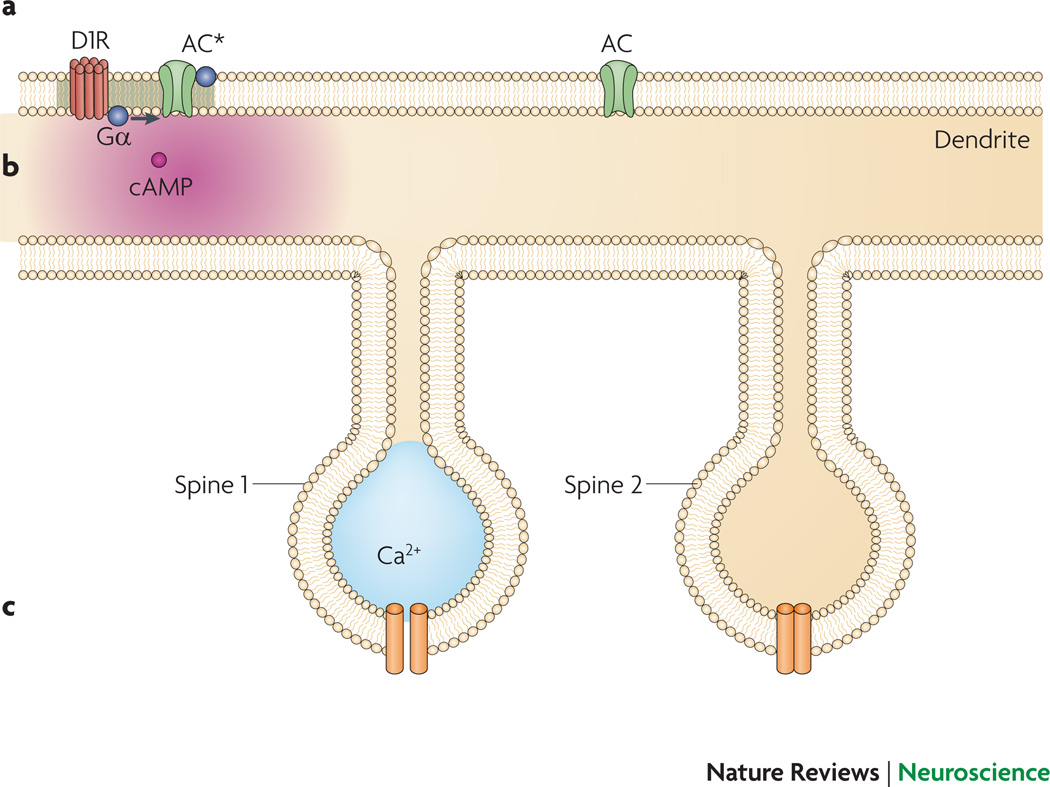

Display 3: Figure 3.

Spatial representation of a dendrite plus multiple dendritic spines are required to address input specificity and microdomains.

A. G proteins diffuse laterally within the membrane to activate adenylyl cyclase. Limited mobility, coupled with RGS activity keeps cyclase activation (AC*) confined to a region near the receptor, whereas AC further away remains inactive.

B. cAMP diffuses rapidly within the cytosol; thus, a gradient of cAMP is less steep than that of active cyclase, unless mechanisms to maintain the gradient are present, such as localized PDEs.

C. Synaptic activation of spine 1, but not spine 2, results in calcium elevation in spine 1, which remains limited to this spine by buffers and pumps. Otherwise, diffusion would carry the calcium message to spine 2, resulting in reduced synaptic specificity.

A voxel based spatial stochastic model was used to demonstrate an unexpected role of Regulators of G Protein Signaling (RGS) for G protein receptor response properties63. RGS are important for turning off G protein coupled receptors in many cell types, including neurons. The model helped to explain the mechanism that underlies a paradoxical experimental result: that the acceleration of GTP hydrolysis by RGS can enhance G protein activation. Model simulations demonstrated that RGS reduce the depletion of GαGDP near the receptor, permitting rapid re-coupling of receptor to G protein for subsequent receptor activation. RGS also helps spatial focusing of receptor activation: accelerated GTP hydrolysis reduces the diffusion of active G protein, limiting the spatial extent of G protein coupled receptor activity. Similarly, PDE4 focuses cAMP signaling by causing fast hydrolysis of cAMP, which results in a higher cAMP concentration at the membrane, near the adenylyl cyclase source64, 65.

Models of molecular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity

The past 10 years has seen a burgeoning of the systems biology approach to synaptic plasticity. Not surprisingly, the models of synaptic plasticity span similar techniques, approaches and scales as those used in systems biology. The computational approaches most commonly apply deterministic equations66, 67, although more recently, stochastic simulations have been used as well68, 69. Similar to systems biology, many of the synaptic plasticity models involve one or a few spatial compartments; however, an increasing number of models involve extended spatial scale and diffusion that better fit the unique morphology of neurons70–72. All of the models below focus on a subset of events involved in induction of synaptic plasticity, regardless of the persistence of molecule activation following induction.

Role of calcium-activated pathways in LTP

Several computational models have explored mechanisms by which CaMKII can be persistently activated on a time scale that is comparable to the duration of long-term synaptic plasticity. One set of models used the dynamical modeling approach of representing biochemical reactions using ordinary differential equations and algebraic equations. Differential equations described calcium binding to calmodulin, which then binds calcineurin, and CaMKII. Algebraic equations were used to model calcium activation of PKA, and autophosphorylation of CaMKII, which depends on the probability that two adjacent (versus non-adjacent) CaMKII subunits are bound to calcium-calmodulin73–75. One of the main results of these models was that CaMKII remains phosphorylated (and thus active) by anchoring to proteins in the postsynaptic density, and thus was protected from phosphatases74. Another prediction, based on evaluation of equilibrium points, was that CaMKII activity exhibits bistability75.

Another set of models of CaMKII phosphorylation employ non-spatial stochastic methods required by the small size of the spine and the postsynaptic density. Small numbers of each molecule species are present in the spine; thus, molecular reactions and movements occur with some random variation. Stochastic models of CaMKII activation can address questions such as whether in vitro experimental observations76 and results from deterministic models are valid in the presence of random fluctuations68, 77, 78. One stochastic model included calcium influx through the NMDA receptor and showed that the sensitivity of calcium dynamics to input stimulation frequency faithfully propagates downstream to CaMKII77. One of the most exciting results, demonstrated with a model that included protein turnover by replacing phosphorylated with unphosphorylated CaMKII subunits, has been that synaptic stimulation can produce reliable and persistent phosphorylation of CaMKII68. Nonetheless, this model does not explain the molecule mechanisms underlying late-phase LTP induction, which require transcription and translation.

Signaling pathways implicated in synaptic plasticity

The importance of interactions between signaling pathways has been demonstrated in computational models of cerebellar LTD, in which paired stimulation of climbing fibers (CF) and parallel fibers (PF) is required to produce long-term depression79, 80. Several differential equation models include PF activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors, whose activation leads to diacylglycerol production and PKC activation, and CF stimulation activating voltage-dependent calcium channels67, 81. One model also included a feedback loop between MAPK and PKC81 as a mechanism for bistability. Simulations confirmed that conjunctive stimulation of CF and PF stimulation is required for persistent LTD82. A subsequent model67 which did not include MAPK activation but did include the release of calcium through IP3 receptor channels, investigated the compelling question of whether the activation of PKC is sensitive to the temporal interval between PF and CF stimulation. An emergent feature of this model was that such temporal sensitivity indeed exists and that it matches that observed in experiments of classical conditioning, a cerebellum-dependent type of learning83. The model further predicted that the temporal sensitivity was conveyed by several molecules, including IP3R and PKC67. A limitation of all these models is whether the results hold when processes in the spine are modeled stochastically, and spatially separated from the dendrites.

Another region of the brain where pairing of inputs is essential for learning is the striatum, which receives inputs from both the cortex and the substantia nigra. A differential equation model of calcium- and dopamine-activated signaling pathways66 reproduced many experimental measurements of DARPP32 phosphorylation84–86 on Thr34 and Thr75. The novel finding from this model was that the response to transient stimulation (which represents the cortical and nigral activity during reward learning in behavioural experiments), differs from the response to continuous stimulation: a prolonged calcium elevation reduces, whereas transient calcium elevation enhances Thr34 phosphorylation of DARPP32.

Both this and another differential equation model87, which in addition included phosphorylation of DARPP32 on Ser102 and Ser137, further predicted that a large calcium-dependent enhancement of PP2A was crucial for explaining the observed calcium-dependent decrease in Thr75 phosphorylated DARPP3288. This calcium dependent activation of PP2A was subsequently tested experimentally89: the results indicated that although PP2A activity was enhanced by calcium increases, the enhancement was significantly less than what was predicted to account for the significant dephosphorylation of Thr75. Thus, perhaps more valuable than confirming prior experiments, these models combined with experimental investigation discovered that additional signaling pathways are required to explain the experimental results, and that further investigation is needed.

A systems biology approach to synaptic plasticity

An alternative to including a subset of signaling pathways (as done above) is to include all pathways known to be implicated in synaptic plasticity, including MAPK, PKA, CaMKII and PKC, with the aim of identifying functional motifs such as feedback loops, gates and switches that operate in neurons48. Deterministic simulations48, 90, 91 have revealed several emergent properties of the global network of interacting pathways that are not present in individual pathways. These emergent properties include ultrasensitivity, and sensitivity to patterns with specific temporal characteristics. An integration of simulation and experiment investigated the mechanisms underlying sensitivity of LTP to temporal interval of synaptic stimulation. In this comprehensive study91, the simulations demonstrated that phosphorylation of MAPK was sensitive to the temporal interval between stimulus trains; subsequent experiments confirmed the prediction that phosphoMAPK had the same temporal sensitivity as LTP; further simulations demonstrated that temporal sensitivity of PKMζ was an important contributing factor. This modeling approach illuminates the computational possibilities of intracellular signaling cascades, but it doesn’t necessarily demonstrate which of the possible computations are being performed.

The ideal computational model for synaptic plasticity requires stochastic simulation of AMPA receptor phosphorylation at the postsynaptic density. Stochastic simulations69, 92 using a model that includes the same signaling pathways as the deterministic models, revealed spontaneous transitions between states which had been stable in the deterministic model. Thus, the model is not truly bistable, but exhibits a bi-modal distribution. These spontaneous transitions transform switch thresholds into threshold ranges69, 92: switches become either less sensitive to signals or more sensitive to noise. Similarly, the models showed that noise usually degrades sensitivity to temporal pattern, although stochastic resonance can enhance the response to particular temporal intervals. An important question addressed in this context is whether a synapse can exhibit either potentiation, depression, de-potentiation or no change, depending on stimulation pattern. Simulations reveal that PKA phosphorylation of AMPAR together with receptor cycling exhibits bistability (if deterministic), or extremely long time to spontaneously switch states (if stochastic)69 – similar to the bistability mechanism shown for MAPK. This mechanism is independent of the CaMKII bistability suggesting that synapses could exhibit multiple stable states. Nonetheless, under conditions exhibiting extremely low spontaneous state transitions, transient stimulation was unable to produce a state change.

The spatial design of neurons permits significant signal processing capabilities, as is known from compartmental modeling of electrical properties. Imaging (Box 2) has revealed that these spatial aspects, together with anchoring of proteins, produce microdomains of signaling molecules in neurons. Modeling this spatial aspect of neurons and evaluating the role of space is a relatively new approach to investigating neuronal plasticity70, 72 and has led to several fascinating discoveries. A deterministic spatial model of cAMP pathways (including PKA, phosphodiesterase, and MAPK) demonstrated that morphology, in particular the surface-to-volume ratio, is important, but not sufficient for producing spatial microdomains72. Rather, both biochemical network topology and kinetics are essential for the propagation of cAMP microdomains to downstream targets72. The most comprehensive, deterministic spatial model of signaling pathways (including MAPK, PKA, CaMKII and PKC) incorporated a multi-compartmental, multi-channel electrical model of a dendrite. Simulations of this model revealed that unlike calcium waves and action potentials, which propagate rapidly, activation of MAPK throughout the dendrite, which has been observed experimentally, cannot be produced by diffusion or wave-like propagation of feedback loops, but requires stimulation at multiple points along the dendrite70.

In summary, computational models of synaptic plasticity have addressed whether molecules that have been identified so far to be involved in synaptic plasticity can account for experimental observations, and which particular molecular mechanisms are responsible for observations. Simulation and modeling, integrated with imaging experiments, tests whether our understanding of mechanisms is complete, or whether some molecule plays a hitherto unknown function, by making explicit the assumptions that are implicit in conceptual models.

Future directions

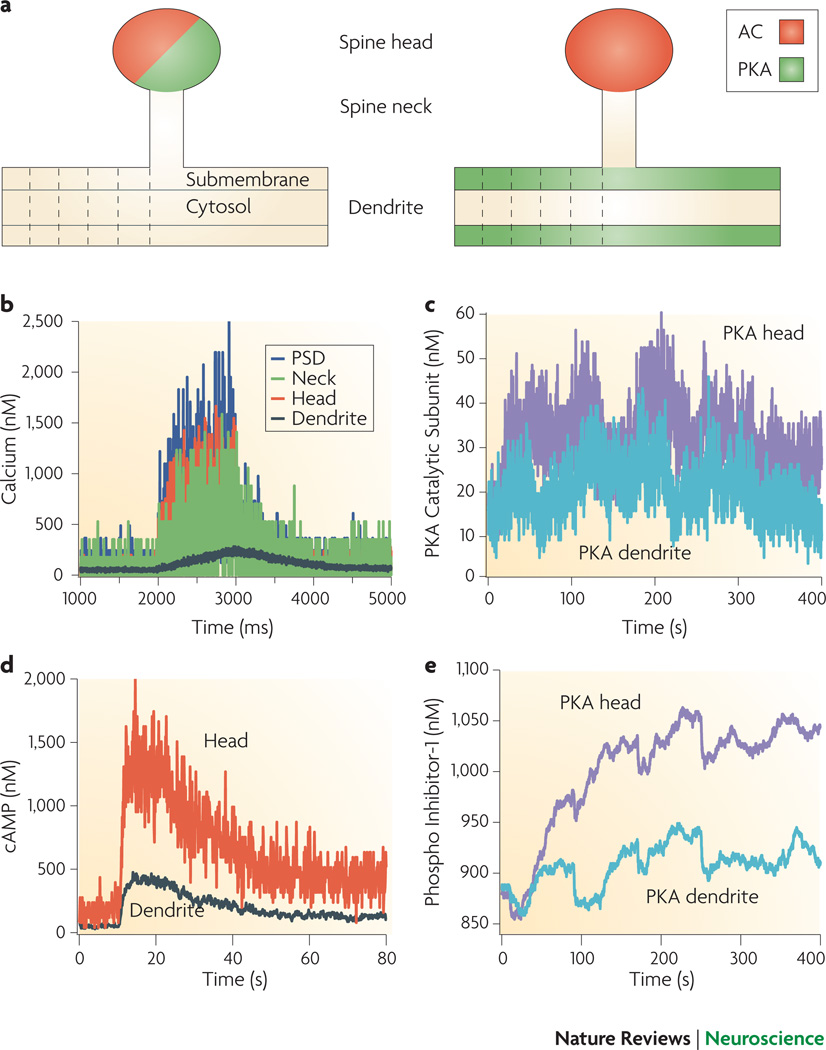

Expanding computational models of synaptic plasticity beyond a subset of relevant pathways and limited spatial domains requires a close interaction with imaging and cell biology. The explosion of imaging techniques has provided high-resolution data, both in the spatial and in the temporal domain, e.g. protein mobility and the dynamics of interactions with other proteins, to improve the reliability and veracity of computational models. Recent developments in spatial stochastic simulation techniques61, 93, 94 (Figure 4A) allow the assessment of the role of microdomains resulting from neuron morphology (spines) and anchoring proteins (such as A kinase anchoring proteins) within a model of the larger volume of a dendrite with multiple spines (Figure 4B). A spatial stochastic model of intracellular spine calcium dynamics demonstrated that calcium activation of calmodulin is sensitive to temporal interval between pre-synaptic glutamate release and the post-synaptic action potential95. Despite these advancements in simulation techniques, development of large scale simulations is exceedingly difficult due to the lack of information about concentrations of enzymes and subcellular spatial localization. Nonetheless such large scale simulations are useful for assessing whether a proposed biological mechanism is plausible, and for evaluating alternative hypotheses.

Display 4: Figure 4.

Spatial stochastic simulations using NeuroRD evaluate the role of anchoring proteins and microdomains in synaptic plasticity of hippocampal area CA1 (Kim, Chay, Blackwell; personal communication). A. NeuroRD is software for simulating stochastic reaction-diffusion systems in complex 3-D morphologies on a mesoscopic scale65. The software merges a mesoscopic diffusion algorithm62 with elements of the tau-leap reaction algorithm53. The dendrite is subdivided into submembrane region and cytosolic region, and each region is further subdivided into voxels. Similarly, the spine is subdivided into head and neck voxels. Probability of reaction and diffusion are calculated from the voxel geometry, and either diffusion constant or reaction constant. Given the reaction and diffusion probabilities, each timestep involves generating the numbers of particles diffusing across each possible boundary, the number of reactions occurring, and updating the numbers of particles of each type in each voxel accordingly. The molecules and reactions in the system include the DaR1 and calcium activated pathways illustrated in Figure 1B, but do not include MAPK pathways, Gαi or Gαq coupled pathways. In both cases Da1R, G protein, AC1/8 are localized in the spine. In one condition, PKA is co-localized with AC in the spine (left), in the other condition, PKA is anchored to the dendrite submembrane. B. In both conditions, there is a calcium gradient from spine to dendrite. C. AC produces cAMP in the spine head, which diffuses into the dendrite, creating a gradient of cAMP. D. The gradient of cAMP leads to higher PKA activation when PKA is co-localized in the spine head. E. The difference in PKA activation propagates downstream to yield greater phosphorylation of Inhibitor1 or PP1 when PKA is in the spine.

Modeling the signaling pathways by themselves is not sufficient for understanding synaptic plasticity. A blending of techniques96 that permit integration with multi-compartmental, electrical models is essential because of the complexity of interactions among membrane potential, ion channels and calcium dynamics. Mutual interactions between membrane potential and ion channels constitute a feedback loop, as do the interactions between ion channels and calcium dynamics. Future models should include modulation of voltage-dependent channels, crucial for plasticity of intrinsic excitability, which in turn controls synaptic plasticity through altering the membrane potential (Figure 5).

Display 5: Figure 5.

Computational neuroscience in the future will A. integrate systems biology approaches to modeling the signaling pathways underlying synaptic plasticity with computational neuroscience approaches to modeling electrical activity in the neuron. Both ionotropic and metabotropic receptors are activated by simulated synaptic inputs resulting from ongoing network activity. Membrane depolarization produces calcium influx through voltage dependent calcium channels, and in turn, calcium dependent potassium channels modify membrane potentiation. Both calcium and receptor activated signaling pathways activate kinases and phosphotases which may modify channel properties. B. Networks of such model neurons are required to understand the development of plasticity in response to realistic neuronal firing patterns, and to understand how the plasticity in turn modifies network activity. Thus, multiple copies of the neuron model of electrical and chemical events will be connected to each other with synapses. C. Neuroinformatics databases and tools will play a key role in facilitating development of large scale data-driven models, ranging from molecules to network connections. The information in the databases range from neuron morphology, to kinetics of signaling pathways and ionic channels, and will be used to create more realistic neuron models.

Approaches for bridging temporal and spatial scales are also important for investigating gene expression and structural changes, which are required for memory storage and late-phase LTP and LTD. Recent models have begun to address the role of local protein synthesis in LTP97. Ever more powerful, efficient and multi-scale computational algorithms are required to simulate the movement of molecules, such as transcription initiation factors, mRNA, and proteins, over long distances. Thus, modeling gene expression and memory storage requires integration of millisecond processes with long time scales (hours) and submicron compartments with large spatial scales (mm).

All of these computational and scientific advancements will require matching advancements in neuroinformatics and bioinformatics techniques for extracting and integrating quantitative and dynamic information, so that this information can be used in computational investigations. Of particular relevance are databases of signaling pathways, rate constants, protein quantities in different brain regions and cell types.

Furthermore, plasticity of synaptic and ion channels interacts non-linearly with neuronal network activity, which in turn influences plasticity mechanisms (yet additional feedback loops). Thus, the development of synaptic plasticity and its consequences for network activity and behavior requires simulating large-scale networks of such neurons. Computational models of this scope will have broad applications, for example, they might be useful for investigation of mechanisms underlying disorders that are characterized by memory impairments.

Acknowledgments

J H Kotaleski was supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Parkinson's Foundation, and K T Blackwell was supported by an HFSP program grant, the joint NSF-NIH CRCNS program through NIH grant R01 AA16022 and RO1 AA18060. Also we have received comments on this draft by Ted Abel and Rebekah Evans.

The following glossaries are to be defined

- Network and graph theory

The study of the interconnectedness of related items. The nodes or vertices of a graph are individual items, and two nodes are linked with an edge if they influence each other.

- Boolean logic network

A network with nodes that take one of two values, e.g. on or off (here corresponding to activated or non-activated genes). Dynamics of the network are simulated using logical operations coupled with explicit time delays.

- Deterministic model

In the present context a model that calculates molecule concentrations using differential equations and algebraic equations.

- Partial differential equation

An equation that describes how one variable depends on several other variables such as time and space. Here an equation specifying rate of change in a molecule quantity as a function of the spatial gradient.

- Stochastic methods

Computational approaches employing random number generators, i.e., Monte Carlo methods that are governed by rules of chance.

- Current clamp mode

used for measuring membrane potential in response to current injection.

- Markov kinetic model

A description of ion channel gating in which the change in channel conformation from one state to another state depends only on the current state and not on past history.

- Cable equation

Describes the flow of electrical current along a wire, dendrite or axon.

- Low pass filter

Reduces the amplitude of high frequency signals, while leaving low frequency signals unaltered.

- Resistive-capacitive models

Modeling a small neuronal compartment as a resistive element in parallel with a capacitor, and modeling dendrites as a connected set of these elements.

- Bistability

The existence of two stable or equilibrium states for the same input, which requires hysteresis.

- Hysteresis

Different input-output curves are obtained depending upon whether inputs are increasing from a low value or whether inputs are decreasing from a high value.

- Ultrasensitive

A graded response in which a small change in the input produces a large change in the output.

- Dynamics

Time dependent changes in activity or quantity or some other variable.

- Kinetics

Rates at which particular reactions or diffusion occur.

- Molecular crowding

The volume occupied by molecules is so large that molecules cannot diffuse freely in the cytoplasm. Reactions are either impeded or enhanced depending on proximity of reacting molecules.

Reference List

- 1.Coba MP, et al. Neurotransmitters drive combinatorial multistate postsynaptic density networks. Sci. Signal. 2009;2:ra19. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins MO, et al. Proteomic analysis of in vivo phosphorylated synaptic proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5972–5982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411220200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daoudal G, Debanne D. Long-term plasticity of intrinsic excitability: learning rules and mechanisms. Learn. Mem. 2003;10:456–465. doi: 10.1101/lm.64103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debanne D. Associative synaptic plasticity in hippocampus and visual cortex: cellular mechanisms and functional implications. Rev. Neurosci. 1996;7:29–46. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1996.7.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Citri A, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:18–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynch G, Larson J, Kelso S, Barrionuevo G, Schottler F. Intracellular injections of EGTA block induction of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Nature. 1983;305:719–721. doi: 10.1038/305719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malenka RC, Kauer JA, Zucker RS, Nicoll RA. Postsynaptic calcium is sufficient for potentiation of hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science. 1988;242:81–84. doi: 10.1126/science.2845577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bear MF, Cooper LN, Ebner FF. A physiological basis for a theory of synapse modification. Science. 1987;237:42–48. doi: 10.1126/science.3037696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lisman J. A mechanism for the Hebb and the anti-Hebb processes underlying learning and memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:9574–9578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nevian T, Sakmann B. Spine Ca2+ signaling in spike-timing-dependent plasticity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11001–11013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1749-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adermark L, Lovinger DM. Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling at striatal synapses requires a regulated postsynaptic release step. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:20564–20569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706873104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman DE. Synaptic mechanisms for plasticity in neocortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;32:33–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abel T, et al. Genetic demonstration of a role for PKA in the late phase of LTP and in hippocampus-based long-term memory. Cell. 1997;88:615–626. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81904-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shema R, Sacktor TC, Dudai Y. Rapid erasure of long-term memory associations in the cortex by an inhibitor of PKM ζ. Science. 2007;317:951–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1144334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao Y, et al. PKM ζ maintains late long-term potentiation by N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor/GluR2-dependent trafficking of postsynaptic AMPA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7820–7827. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0223-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelleher RJ, III, Govindarajan A, Jung HY, Kang H, Tonegawa S. Translational control by MAPK signaling in long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 2004;116:467–479. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sweatt JD. The neuronal MAP kinase cascade: a biochemical signal integration system subserving synaptic plasticity and memory. J Neurochem. 2001;76:1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.pergis-Schoute AM, Debiec J, Doyere V, LeDoux JE, Schafe GE. Auditory fear conditioning and long-term potentiation in the lateral amygdala require ERK/MAP kinase signaling in the auditory thalamus: a role for presynaptic plasticity in the fear system. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5730–5739. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0096-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shouval HZ, Bear MF, Cooper LN. A unified model of NMDA receptor-dependent bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:10831–10836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152343099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song S, Miller KD, Abbott LF. Competitive Hebbian learning through spike-timing-dependent synaptic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:919–926. doi: 10.1038/78829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Rossum MC, Bi GQ, Turrigiano GG. Stable Hebbian learning from spike timing-dependent plasticity. J. Neuroscience. 2000;20:8812–8821. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08812.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes WR, Levy WB. Insights into associative long-term potentiation from computational models of NMDA receptor-mediated calcium influx and intracellular calcium changes. J. Neurophysiology. 1990;63:1148–1168. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.5.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiegg A, Gerstner W, Ritz R, Leo van Hemmen J. Intracellular Ca2+ stores can account for the time course of LTP Induction: A model of CA2+ Dynamics in dendritic spines. American Physiological Society. 1985;74:1046–1055. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.3.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gamble E, Koch C. The dynamics of free calcium in dendritic spines in response to repetitive synaptic input. Science. 1987;236:1311–1315. doi: 10.1126/science.3495885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zador A, Koch C, Brown TH. Biophysical model of a Hebbian synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:6718–6722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitano H. Systems biology: a brief overview. Science. 2002;295:1662–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.1069492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong H, Tombor B, Albert R, Oltvai ZN, Barabasi AL. The large-scale organization of metabolic networks. Nature. 2000;407:651–654. doi: 10.1038/35036627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bullmore E, Sporns O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009;10:186–198. doi: 10.1038/nrn2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma'ayan A. Insights into the organization of biochemical regulatory networks using graph theory analyses. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:5451–5455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800056200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lockhart DJ, Winzeler EA. Genomics, gene expression and DNA arrays. Nature. 2000;405:827–836. doi: 10.1038/35015701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tyers M, Mann M. From genomics to proteomics. Nature. 2003;422:193–197. doi: 10.1038/nature01510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rual JF, et al. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–1178. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wenk MR. The emerging field of lipidomics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005;4:594–610. doi: 10.1038/nrd1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watts DJ, Strogatz SH. Collective dynamics of 'small-world' networks. Nature. 1998;393:440–442. doi: 10.1038/30918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noorbakhsh F, Overall CM, Power C. Deciphering complex mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases: the advent of systems biology. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bromberg KD, Ma'ayan A, Neves SR, Iyengar R. Design logic of a cannabinoid receptor signaling network that triggers neurite outgrowth. Science. 2008;320:903–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1152662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor IW, et al. Dynamic modularity in protein interaction networks predicts breast cancer outcome. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:199–204. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Husi H, Ward MA, Choudhary JS, Blackstock WP, Grant SG. Proteomic analysis of NMDA receptor-adhesion protein signaling complexes. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:661–669. doi: 10.1038/76615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan TJ, Grant SG. The origin and evolution of synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferrell JE., Jr Self-perpetuating states in signal transduction: positive feedback, double-negative feedback and bistability. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:140–148. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00314-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolf DM, Arkin AP. Motifs, modules and games in bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003;6:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ingram PJ, Stumpf MP, Stark J. Network motifs: structure does not determine function. BMC. Genomics. 2006;7:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Novak B, Tyson JJ. Design principles of biochemical oscillators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:981–991. doi: 10.1038/nrm2530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauro HM, Kholodenko BN. Quantitative analysis of signaling networks. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2004;86:5–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Megason SG, Fraser SE. Imaging in systems biology. Cell. 2007;130:784–795. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smolen P, Baxter DA, Byrne JH. Modeling transcriptional control in gene networks--methods, recent results, and future directions. Bull. Math. Biol. 2000;62:247–292. doi: 10.1006/bulm.1999.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heinrich R, Neel BG, Rapoport TA. Mathematical models of protein kinase signal transduction. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:957–970. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00528-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhalla US, Iyengar R. Emergent properties of networks of biological signaling pathways. Science. 1999;283:381–387. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kholodenko BN. Negative feedback and ultrasensitivity can bring about oscillations in the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:1583–1588. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Markevich NI, Hoek JB, Kholodenko BN. Signaling switches and bistability arising from multisite phosphorylation in protein kinase cascades. J. Cell Biol. 2004;164:353–359. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kolch W, Calder M, Gilbert D. When kinases meet mathematics: the systems biology of MAPK signalling. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1891–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hornberg JJ, et al. Principles behind the multifarious control of signal transduction. ERK phosphorylation and kinase/phosphatase control. FEBS J. 2005;272:244–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gillespie DT. Stochastic simulation of chemical kinetics. Annu. Rev Phys. Chem. 2007;58:35–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stein M, Gabdoulline RR, Wade RC. Bridging from molecular simulation to biochemical networks. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smolen P, Baxter DA, Byrne JH. Interlinked dual-time feedback loops can enhance robustness to stochasticity and persistence of memory. Phys. Rev. E. Stat. Nonlin. Soft. Matter Phys. 2009;79:031902. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.79.031902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brandman O, Ferrell JE, Jr, Li R, Meyer T. Interlinked fast and slow positive feedback loops drive reliable cell decisions. Science. 2005;310:496–498. doi: 10.1126/science.1113834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takahashi K, Arjunan SN, Tomita M. Space in systems biology of signaling pathways--towards intracellular molecular crowding in silico. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1783–1788. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coggan JS, et al. Evidence for ectopic neurotransmission at a neuronal synapse. Science. 2005;309:446–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1108239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shimizu TS, et al. Molecular model of a lattice of signalling proteins involved in bacterial chemotaxis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000;2:792–796. doi: 10.1038/35041030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lipkow K, Andrews SS, Bray D. Simulated diffusion of phosphorylated CheY through the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:45–53. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.1.45-53.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hattne J, Fange D, Elf J. Stochastic reaction-diffusion simulation with MesoRD. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2923–2924. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blackwell KT. An efficient stochastic diffusion algorithm for modeling second messengers in dendrites and spines. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2006;157:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhong H, et al. A spatial focusing model for G protein signals. Regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) protien-mediated kinetic scaffolding. J Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7278–7284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Terrin A, et al. PGE(1) stimulation of HEK293 cells generates multiple contiguous domains with different [cAMP]: role of compartmentalized phosphodiesterases. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:441–451. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oliveira RF, et al. The role of type 4 phosphodiesterases in generating microdomains of cAMP: large scale stochastic simulations. Neuroinformatics. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011725. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lindskog M, Kim M, Wikstrom MA, Blackwell KT, Kotaleski JH. Transient calcium and dopamine increase PKA activity and DARPP-32 phosphorylation. PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2006;2:e119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hellgren Kotaleski J, Lester DS, Blackwell KT. Subcellular interactions between parallel fibre and climbing fibre signals in Purkinje cells predict sensitivity of classical conditioning to interstimulus interval. Integrative Physiological and Behavioral Science. 2002;37:265–292. doi: 10.1007/BF02734249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miller P, Zhabotinsky AM, Lisman JE, Wang XJ. The stability of a stochastic CaMKII switch: dependence on the number of enzyme molecules and protein turnover. PLoS. Biol. 2005;3:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hayer A, Bhalla US. Molecular switches at the synapse emerge from receptor and kinase traffic. PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2005;1:137–154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ajay SM, Bhalla US. A propagating ERKII switch forms zones of elevated dendritic activation correlated with plasticity. HFSP. J. 2007;1:49–66. doi: 10.2976/1.2721383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Blackwell KT. Paired turbulence and light do not produce a supralinear calcium increase in Hermissenda. J. Comput. Neurosci. 2004;17:81–99. doi: 10.1023/B:JCNS.0000023866.88225.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Neves SR, et al. Cell shape and negative links in regulatory motifs together control spatial information flow in signaling networks. Cell. 2008;133:666–680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kubota Y, Bower JM. Transient versus asymptotic dynamics of CaM kinase II: possible roles of phosphatase. J. Comput. Neurosci. 2001;11:263–279. doi: 10.1023/a:1013727331979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lisman JE, Zhabotinsky AM. A model of synaptic memory: a CaMKII/PP1 switch that potentiates transmission by organizing an AMPA receptor anchoring assembly. Neuron. 2001;31:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Graupner M, Brunel N. STDP in a bistable synapse model based on CaMKII and associated signaling pathways. PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Koninck P, Schulman H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science. 1998;279:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Holmes WR. Models of calmodulin trapping and CaM kinase II activation in a dendritic spine. J. Comput. Neurosci. 2000;8:65–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1008969032563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dosemeci A, Albers RW. A mechanism for synaptic frequency detection through autophosphorylation of CaM kinase II. Biophys. J. 1996;70:2493–2501. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79821-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ito M. The molecular organization of cerebellar long-term depression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:896–902. doi: 10.1038/nrn962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schreurs BG, Oh MM, Alkon DL. Pairing-specific long-term depression of Purkinje cell excitatory postsynaptic potentials results from a classical conditioning procedure in rabbit. J. Neurophysiology. 1996;75:1051–1060. 1051–1060. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.3.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kuroda S, Schweighofer N, Kawato M. Exploration of signal transduction pathways in cerebellar long-term depression by kinetic simulation. J. Neuroscience. 2001;21:5693–5702. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05693.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Daniel H, Hemart N, Jaillard D, Crepel F. Coactivation of metabotropic glutamate receptors and of voltage-gated calcium channels induces long-term depression in cerebellar Purkinje cells in vitro. Exp. Brain Res. 1992;90:327–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00227245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gormezano I, Kehoe EJ, Marshall BJ. Twenty years of classical conditioning research with the rabbit. Prog Psychobiol and Physiol Psych. 1983;10:192–275. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nishi A, Snyder GL, Greengard P. Bidirectional regulation of DARPP-32 phosphorylation by dopamine. J. Neuroscience. 1997;17:8147–8155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08147.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nishi A, et al. Amplification of dopaminergic signaling by a positive feedback loop. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:12840–12845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220410397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Snyder GL, et al. Regulation of AMPA receptor dephosphorylation by glutamate receptor agonists. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:703–713. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fernandez E, Schiappa R, Girault JA, Le NN. DARPP-32 is a robust integrator of dopamine and glutamate signals. PLoS. Comput. Biol. 2006;2:e176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nishi A, et al. Regulation of DARPP-32 dephosphorylation at PKA- and Cdk5-sites by NMDA and AMPA receptors: distinct roles of calcineurin and protein phosphatase-2A. J. Neurochem. 2002;81:832–841. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ahn JH, et al. The B''/PR72 subunit mediates Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation of DARPP-32 by protein phosphatase 2A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:9876–9881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703589104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bhalla US. Mechanisms for temporal tuning and filtering by postsynaptic signaling pathways. Biophys. J. 2002;83:740–752. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75205-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ajay SM, Bhalla US. A role for ERKII in synaptic pattern selectivity on the time-scale of minutes. Eur. J Neurosci. 2004;20:2671–2680. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bhalla US. Signaling in small subcellular volumes. II. Stochastic and diffusion effects on synaptic network properties. Biophys. J. 2004;87:745–753. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.040501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Andrews SS, Bray D. Stochastic simulation of chemical reactions with spatial resolution and single molecule detail. Phys. Biol. 2004;1:137–151. doi: 10.1088/1478-3967/1/3/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Takahashi K, Kaizu K, Hu B, Tomita M. A multi-algorithm, multi-timescale method for cell simulation. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:538–546. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Keller DX, Franks KM, Bartol TM, Jr, Sejnowski TJ. Calmodulin activation by calcium transients in the postsynaptic density of dendritic spines. PLoS. ONE. 2008;3:e2045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ray S, Bhalla US. PyMOOSE: Interoperable Scripting in Python for MOOSE. Front Neuroinformatics. 2008;2:6. doi: 10.3389/neuro.11.006.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Aslam N, Kubota Y, Wells D, Shouval HZ. Translational switch for long-term maintenance of synaptic plasticity. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:284. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Perkel DJ, Petrozzino JJ, Nicoll RA, Connor JA. The role of Ca2+ entry via synaptically activated NMDA receptors in the induction of long-term potentiation. Neuron. 1993;11:817–823. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bear MF, Kirkwood A. Neocortical long-term potentiation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1993;3:197–202. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90210-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Otmakhov N, Griffith LC, Lisman JE. Postsynaptic inhibitors of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II block induction but not maintenance of pairing-induced long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5357–5365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05357.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lisman J, Schulman H, Cline H. The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioural memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:175–190. doi: 10.1038/nrn753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wong ST, et al. Calcium-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity is critical for hippocampus-dependent long-term memory and late phase LTP. Neuron. 1999;23:787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mons N, Cooper DM. Selective expression of one Ca(2+)-inhibitable adenylyl cyclase in dopaminergically innervated rat brain regions. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1994;22:236–244. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Svenningsson P, et al. DARPP-32: an integrator of neurotransmission. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004;44:269–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mulkey RM, Endo S, Shenolikar S, Malenka RC. Involvement of a calcineurin/inhibitor-1 phosphatase cascade in hippocampal long-term depression. Nature. 1994;369:486–488. doi: 10.1038/369486a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rall W. Branching dendritic trees and motoneuron membrane resistivity. Exp. Neurol. 1959;1:491–527. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(59)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Ellisman MH, Tsien RY. The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science. 2006;312:217–224. doi: 10.1126/science.1124618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Patterson GH. Development and use of fluorescent protein markers in living cells. Science. 2003;300:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1082520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Carlson HJ, Campbell RE. Genetically encoded FRET-based biosensors for multiparameter fluorescence imaging. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2009;20:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee SJ, Escobedo-Lozoya Y, Szatmari EM, Yasuda R. Activation of CaMKII in single dendritic spines during long-term potentiation. Nature. 2009;458:299–304. doi: 10.1038/nature07842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Harvey CD, Yasuda R, Zhong H, Svoboda K. The spread of ras activity triggered by activation of a single dendritic spine. Science. 2008;321:136–140. doi: 10.1126/science.1159675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]