INTRODUCTION

Over a hundred delegates from 24 countries met in Melbourne, Australia at the 15th Biennial Meeting of the International Gynecologic Cancer Society meeting in November 2014, with representation from 28 member groups Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) and 13 non-GCIG-affiliated sites from low- to middle-income countries. The core purpose of the meeting was to develop consensus around several concepts, which could be taken forward by GCIG for international collaborative trials in cervical cancer. Most of the world’s diseases occur in underdeveloped countries, which do not have adequate resources to conduct research nor provide state-of-the-art treatment. It is becoming increasingly important to involve international centers from resource-poor countries with high caseloads, who are also capable of providing an international standard of care and have appropriate infrastructure in collaborative clinical trials. National and international barriers should be identified for trials dedicated to cervical cancers. Delegates initially reviewed summaries and prioritized key issues for research towards agreement of a new set of trial concepts for the future treatment of cervical cancer. Despite the obvious disparities between the developing world and GCIG member groups/countries, the focus of this document is clinical trials in adequately resourced environments. Screening, prevention, and development of clinical trial opportunities in underdeveloped countries were identified as high unmet medical needs but adequately addressing the economic and operational challenges surrounding these opportunities were beyond the scope of this brainstorming meeting.

Clinical Trial Design Issues

What is the appropriate endpoint? Should we do phase II or phase III studies?

Ten GCIG member groups responded to a survey with nine questions sent to all twenty-six GCIG member groups. Proposed primary endpoints included overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS), and response rates (ORR). Secondary endpoints included PFS, quality of life (QOL), patient reported outcomes (PRO), and safety. In performing phase II or phase III trials, patient population, resources, and results should be considered. The gold standard for phase III studies remains OS but PFS may be beneficial when associated with PRO improvements. PFS and ORR as good surrogates (see below) for clinical activity in smaller phase II studies. Randomization is preferred. Blinding should be considered when randomization is employed. The role of central radiologic review committees is untested in cervical cancer. Finally, it was recommended that the GCIG increase its participation in phase II trials instead of insisting on phase III studies, to avoid the risk of becoming irrelevant to the new world of targeted therapies. Another reason for participation in phase II trials is the probability of some targeted therapies to achieve higher than estimated significance between the study arms despite the usually small patients numbers due to impressive Hazard Ratio which in turn may lead to a positive vote from the worldwide Medical Officer of Health Agencies. However, it still makes sense to ask for phase 3 studies since good results in selected phase 2 populations might not necessarily lead to positive phase 3 studies.

Surrogate Markers (as endpoints)

Surrogate endpoints are often used when a clinical endpoint of interest is rare, distant in time, or unduly invasive, uncomfortable or expensive to measure. Common examples from cancer trials are PFS or ORR (based on change in tumor size using imaging or other biomarkers) as surrogates for OS. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) uses the following definition: A surrogate endpoint of a clinical trial is a laboratory measurement or a physical sign used as a substitute for a clinically meaningful endpoint that measures directly how a patient feels, functions or survives [1]. Whenever possible, clinically meaningful endpoints that directly measure how a patient feels, functions, or survives should be used. Caution is warranted when using surrogate endpoints not validated for the intervention of interest.

What is the control arm and endpoint?

Control groups have one major purpose: to allow discrimination of patient outcomes caused by the test treatment from outcomes caused by other factors, such as the natural progression of the disease, observer or patient expectations, or other treatment. The control group experience reports what would have happened to patients if they had not received the test treatment or if they had received a different treatment known to be effective. When selecting the appropriate controls, the key issue to consider is what are the main objectives of the study. Depending on the objectives of the trials, definition, and selection of control groups change.

Unanswered questions and priority areas for further study

Early cervical cancer

Fertility sparing/preserving, node studies

Optimal management of bulky IB (2–5 cm) cervical cancer in young women wishing to preserve fertility

The surgical technique of radical trachelectomy has evolved over the last 20 years, but collectively, the data indicate that the procedure is a safe option for young women with small volume disease (< 2 cm). In such lesions, radical trachelectomy is now considered standard of care (NCCN guidelines version 2.2015). However, the optimal management of women with larger size lesions (2–5 cm) is unclear. There are actually 2 options: first, is upfront radical trachelectomy (mostly performed abdominally) which allows good radicality in terms of length of parametrial resection, but is associated with a significant risk of positive nodes and with a significant risk of requiring adjuvant chemoradiation therapy according to the presence of intermediate risk factors on final pathology. Second, is neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) followed by fertility preserving surgery (FPS) preceeded by a laparoscopic lymph node assessment to triage and exclude node-positive patients [2]. Complete or optimal responses (<3 mm residual disease) are seen in 80–85% of cases [3]. However, patients with more significant persistent disease post chemotherapy are at higher risk of local recurrent disease. We thus propose a trial to study the role of surgical evaluation of the lymph nodes prior to NACT [2], the ideal chemotherapy regimen and optimal FPS post NACT.

Sentinel node (SLN) mapping in early-stage cervical cancer

The SLN mapping has been introduced in the management of gynecologic malignancies for nearly two decades. Yet, in gynecologic oncology, it is considered standard of care only in vulvar cancer at this point [4]. Although there are numerous publications of SLN mapping in cervical and endometrial cancer, only a few sites perform SLN mapping alone, with most groups still doing complete lymph node dissection in addition to the SLN mapping. The diagnostic accuracy of the technique has been demonstrated in a prospective multi-center clinical trial in early cervix cancer [5]. Quality of life (QOL) and safety issues have also been tested in a randomized trial in SLN negative patients (SLN biopsy vs SLN biopsy + lymph node dissection) (SENTICOL2, NCT01639820). However, some important questions remain: first, these results have been mostly published by “expert” teams and reproducibility of the technique has to be validated in more large-scale practices. Second, ultrastaging of SLN detects “low volume metastasis” such as isolated tumor cells or micrometastases. Lastly, there is a paucity of data with regards to the clinical significance and management of low volume metastasis [6]. Therefore, we propose a prospective multi-center international trial, with a clear algorithm and detailed requirements in terms of: surgeons’ qualifications, sites’ qualifications in terms of infrastructure, pathology qualification to perform careful ultrastaging, standardization of the procedure, and safety/stopping rules.

Locally advanced disease

Prognostic Groupings

FIGO stage 1 and 2 with tumor volume <14 cc. showing no corpus invasion on MRI and node negative on PET scan. The failure rate in this category was 6% for non corpus invasive tumour and 7% for patients with negative nodes on PET. These could be treated effectively with simple hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy. However, not all patients in each FIGO stage are suitably treated with a single modality due to prognostic heterogeneity contained within each FIGO stage, requiring the use of a second or sometimes third treatment modality sequentially, resulting in increased treatment related morbidities and even reduced survival. Following the application of modern radiological imaging, it has become possible to select cervical cancer patients that can be optimally treated using individual treatment modalities thus improving survival and reducing long term morbidity.

In Australia, 610 patients were treated with curative intent between 1996 and 2010 with either surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) or RT. All were staged using FIGO criteria and had pre-treatment MRI and PET/CT. All node negative 1b1 patients were treated with radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection (RHPLND) and adjuvant RT if needed. All other patients were treated with CCRT. In all stages, tumor volume, corpus invasion, and the presence of lymph node metastases were important prognostic factors.

Three distinct prognostic categories emerged: first, FIGO stage 1 and 2 with tumor volume <14 cc. Failure rates in corpus negative or node negative patients were 6% and 7% respectively. These could be treated effectively with simple hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy. Those with corpus invasion or positive nodes had recurrence rate of 15% and 19% respectively. These would require RHPLND if treated by primary surgery and often require adjuvant therapy with radiation, chemotherapy, or both. Second, FIGO stage 1 and 2 with tumor volume >14 cc. Failure rates in corpus negative or node negative patients were 21% and 22% respectively. These could be treated effectively with NACT and RHPLND, if surgery was the preferred option available. Those with corpus invasion or positive nodes had recurrence rate of 39% and 50% respectively. These would require CCRT and perhaps systemic chemotherapy, as this group had 26–38% incidence of distant metastases. Third, FIGO stage 3 and 4a. Corpus and node positivity in this group of patients was 88% and 64% and failure rate of 40% and 60% respectively. All those patients with negative para-aortic nodes may be suitable for pelvic radiation sometimes with an aortic boost. This group can also be used to study effective systemic chemotherapy protocols as 40% of these patients developed systemic metastases. Those with positive para-aortic nodes are the group at highest risk of systemic relapse and hence are a population in which clinical trials testing additional novel maintenance systemic therapies could be tested. Incorporating modern imaging will enable better patient selection for future GCIG studies.

Is there a role for intensity modulation therapy (IMRT) in clinical trials for local advanced cervical cancer?

Radiation therapy is the primary treatment for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. Traditional radiation therapy has side effects including cystitis, proctitis, enteritis, small bowel obstruction, and fistulas. IMRT treats areas of interest while limiting dose to normal tissues and may be a way to reduce toxicity from radiation therapy as well possibly increase dose and therefore improving outcome. There are very few retrospective and small studies evaluating the role of IMRT in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer, but most studies show a reduction in small bowel toxicity and possibility in the reduction of bladder toxicity. IMRT has a role in clinical trials for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer, however it should be used only in sites that treat a large number of patients and have established radiation quality assurance protocols embedded within the trials. Up-to-date contouring atlas and guidelines for imaging during treatment are needed as well as continuous and possibly upfront monitoring for both contouring and planning of patients [7].

International Obstacles and Approaches

Barriers to International Clinical Trials Accrual

Between 1995 and 2005, the number of countries serving as clinical trial sites more than doubled, whereas the proportion of trials conducted in the United States (US) and Western Europe decreased [8]. The US National Clinical Trials Network has recently expanded beyond North America to include Canadian research bases and international collaboration is anticipated for several US based research bases (NRG, SWOG, Alliance, and ECOG-ACRIN). Specific to gynecologic malignancies, GCIG was formalized in 1997 as a collaborative network consisting of representatives from international research groups performing clinical trials in gynecologic cancers. A recent global survey of oncologists regarding the obstacles to international clinical trials cited lack of funds as the most important factor in low- and middle-income countries. Regulatory procedures were ranked as the next most important impediment to clinical research in this setting [9].

The Cervix Cancer Research Network (CCRN)

The CCRN was established by the GCIG following its previous Cervical Cancer State of the Science Meeting held in Manchester in 2009[10]. The vision was to accredit individual sites which could be seen to have sufficiently high quality of treatment and follow-up, as well as adequately trained staff and resourced infrastructure to contribute to international trials according to good clinical practice standards. Protocols were developed for the process of site approval, which included a pre-qualifying questionnaire, a Beam Measurement Program run from Houston, Texas, and a site visit involving volunteer experts from the GCIG generally comprising a radiation oncologist and a trials manager. GCIG volunteers have been very generous with their time and effort in this process. The challenge facing CCRN is one of funding. The International Gynecologic Cancer Society (IGCS), recognizing the potential of the CCRN has generously donated an unrestricted grant to CCRN, which has been matched by the GCIG. The CCRN now sees the need to generate funds to resource new sites through grants from various professional and funding bodies, and possibly industry partnerships.

International Needs and Partnerships

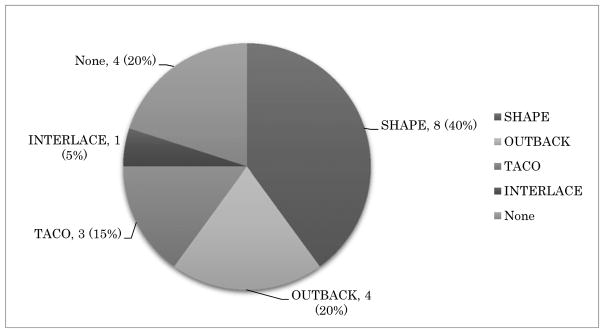

CCRN was designed to provide clinical trials to women in low- and middle-resource settings. Currently, four major clinical trials including three chemo-radiation trial OUTBACK (NCT01414608), INTERLACE (NCT01566240), TACO (NCT01561586) and one surgical trial SHAPE (NCT01658930) are ongoing in GCIG. A survey was performed in order to determine obstacles to GCIG cervical cancer trial accrual and enrollment.

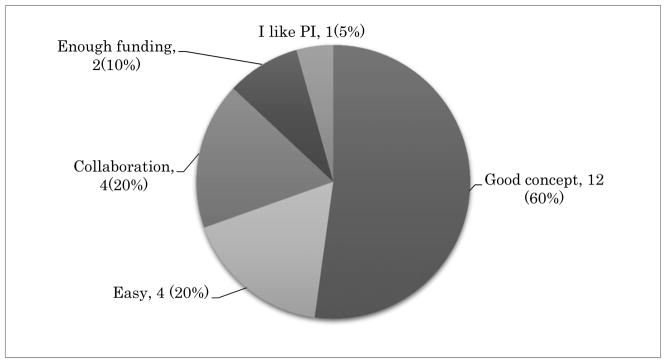

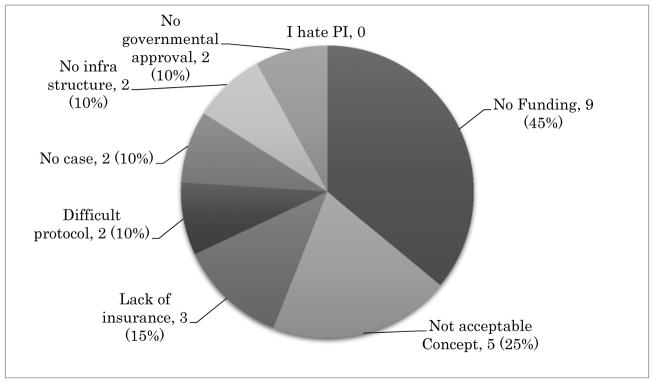

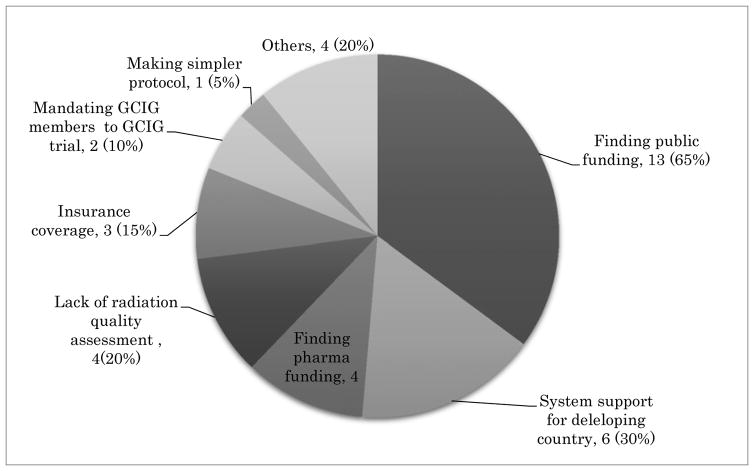

The survey comprised of five multiple-choice questionnaires and was distributed among GCIG member groups and is summarized below. Most GCIG members (13/20, 65%) are actively participating in at least one of four major GCIG protocols as shown in Figure 1. Three groups are participating in non-GCIG cervical cancer protocols (3/20, 15%) and four groups participate in no trials (4/20, 20%). The reasons chosen for participation in GCIG protocols are that the trial has a strong study concept (12/20, 60%), is easy to perform (4/20, 20%), and enhances collaboration between the groups (4/20, 40%) (Figure 2). When asked the reasons for not participating in GCIG trials, funding is revealed to be the main obstacle (Figure 3). The results of this survey suggest that most of the GCIG members consider the concept of the clinical trial is very important, but funding plays a critical role. Our survey shows that an important means for the GCIG to improve participation in international clinical trials is to obtain funding from both public and private sources (17/20, 85%) (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Participating GCIG cervix cancer protocols. A multiple-choice response in 20 GCIG member groups.

Figure 2.

The reason for participating GCIG protocol. A multiple-choice response from 20 GCIG member groups.

Figure 3.

Reasons of difficulty to participating in GCIG clinical trials. Lack of funding (9/20, 45%) is the most important obstacle against international trial participation. A multiple-choice response from 20 GCIG member groups.

Figure 4.

The expected role of GCIG to improve international trial participation. A survey result of multiple-choice (mandated at least one response) from 20 GCIG member groups.

In summary, many obstacles limit GCIG international trial participation, but attracting additional funding sources for implementation of cervical cancer trials appears to be required by countries with low- and middle-income centers. Funding would allow per-case reimbursement for enrollment and support for infrastructure development within lower- and middle-income countries where cervical cancer predominates. There is also a need for future trials to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of shorter fractionation schedules for both palliative and curative treatment of cervical cancer that may be more practical to deliver to women in parts of the developing world with limited access to radiotherapy machines.

Targeted therapy and cervical cancer: a view from the US National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Amongst women diagnosed with advanced and recurrent disease, prognosis is poor. In this setting, systemic chemotherapy is a palliative treatment aimed at prolonging survival and improving QOL. The further development of targeted treatment is a high priority for the NCI and the global cancer care community. The NCI recently opened a prospective precision medicine trial “NCI MATCH” to investigate whether treating molecularly characterized tumors instead of the traditional histologic classification will improve outcomes for patients with cancer [11]. As cervical cancer is a rare disease in high resource settings, the development of anti-cancer agents for cervical cancer becomes challenging. Drug pricing for targeted agents may be prohibitive although solutions such as tiered pricing systems are being developed. These challenges include health care delivery infrastructure, inadequate clinical laboratory services, and fragmented supply chains for drugs. The international drug approval process is subject to local and regional variations and has not yet been harmonized across countries. Results of a recent phase III trial adding bevacizumab to chemotherapy showed that anti-VEGF agents may provide benefit to some patients with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer [12]. Potential targeted agents for future investigation include other antiangiogenic agents, immune-modulators, PARP inhibitors, and inhibitors of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) pathway. Furthermore, possible treatment strategies targeting human papillomavirus (HPV) include therapeutic vaccines (that elicit E6/E7 specific cytotoxic T cell responses), proteosome inhibitors, siRNA targeting E6/E7, and HDAC inhibitors.

Metastatic Cervical Cancer

What is the control arm? Should it include bevacizumab?

In order to detect the best cisplatin-based combination in advanced/recurrent cervical cancer, the GOG 204 trial compared 4 regimens combining cisplatin with paclitaxel, vinorelbine, topotecan, or gemcitabine [13]. There was no significant difference in ORR, PFS, or OS between the various regimens, but the combination of cisplatin/paclitaxel tended to fare better than the other cisplatin-based combinations. However, cisplatin (50mg/m2)/paclitaxel (135mg/m2, 24hr infusion) is an inconvenient regimen as inpatient hospitalization is often required to administer the 24 hour paclitaxel infusion and the hydration to prevent cisplatin renal toxicity. In the randomized JCOG 0505 trial [14], the carboplatin-paclitaxel regimen did not show significant difference in PFS and OS compared to the GOG cisplatin+paclitaxel combination. As the carboplatin-paclitaxel regimen is more convenient and better tolerated, this combination has become a common standard in routine practice.

Small molecules targeting VEFG-R and other angiogenic growth factor receptors have been evaluated in randomized phase II trials in advanced cervical cancer. A significant prolongation of median PFS but not of OS has been observed when pazopanib was compared to lapatinib [15] or when cediranib was compared to placebo in maintenance after up to 6 cycles of carboplatin-paclitaxel, but the benefit of these anti-TKI was limited by toxicity [16]. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy was evaluated in a 4 arm trial (GOG240) [12] in metastatic or recurrent cervical cancer patients treated with paclitaxel combined either with cisplatin or topotecan. No significant difference in efficacy was observed between these two chemotherapy regimens. In contrast, patients treated with bevacizumab+chemotherapy experienced a significant prolongation of median PFS and OS (17.0 vs 13.3 months, hazard ratio 0.71) and this benefit was observed in all the subpopulations. These spectacular results have to be balanced with the increase of severe toxicity for patients in the bevacizumab arm.

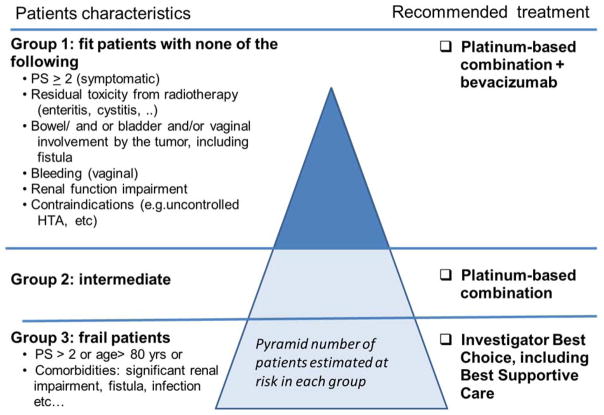

Each improvement in therapeutic efficacy for advanced cervical cancer patients (combination versus single cytotoxic drug, combination chemotherapy + bevacizumab versus combination chemotherapy) results in increased toxicity and the need of a strict selection among this population of fragile patients (Figure 5). In conclusion, the platinum-paclitaxel-bevacizumab regimen could be considered as a standard control arm in trials addressed to selected patients without contraindication to combination chemotherapy and bevacizumab. However, new initiatives should also be proposed for the group of fragile patients who is not able to receive the triple combination.

Figure 5.

Proposed guidelines for treatment of advanced cervix cancer according to patients characteristics

Is a biomarker directed trial in cervix cancer feasible?

Various types of biomarker-directed clinical trial designs can be used. With phase I trials, newer adaptive designs allows for planned expansion in specific molecular subsets. For example, the first human study of Crizotinib, a small molecule inhibitor of ALK and c-MET, began in 2006 and completed initial dose escalation in an unselected cohort of solid tumor patients into a series of molecularly defined expansion cohorts of patients with evidence of ALK or MET activation in specific tumor types [17]. This approach led to successful targeted randomized control trials proving a benefit for Crizotinib compared to 2nd second and 1st first line chemotherapy [18,19]. Alternatively, in an ‘Umbrella’ protocol, different types of treatments are tested in different molecularly selected subsets of a single cancer type, as was done in the often-quoted ‘Battle’ trial in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [20]. These types of designs make efficient use of clinical trial resources within a single clinical trial protocol and may be particularly useful for studying

There have been only a few published reports of profiling of cervical tumors to look for actionable driver mutations. The most common finding has been of abnormalities in the PI3K pathway, as reported by Wright et al. [21] who used the Oncomap platform to interrogate 80 cervical tumors for 1250 mutations in 139 genes. They identified PIK3CA mutations in 31% of cases, with shorter survival times seen in those with a mutation. Ojesina et al. [22] have recently published the findings of deep sequencing of 115 cervix cancers to look for somatic mutations. They identified several novel somatic mutations in the squamous cell carcinomas profiled including E322K substitutions in the MAPK1 gene (8%); inactivating mutations in the HLA-B gene (9%); and mutations in EP300 (16%), FBXW7 (15%), TP53 (5%), and ERBB2 (6%). Discussion concluded that conducting a large randomized GCIG international trial of any one targeted therapy in cervical cancer at present would be challenging. However, smaller biomarker (see below) driven phase II trials should be feasible.

Translational Research

Liquid Biopsies and possible Biomarkers

Cell-free tumor DNA (cfDNA) in the blood (originating from primary as well as metastatic sites) could serve as liquid biopsy reflecting the genetic heterogeneity within a patient. The recent study on the “Landscape of genomic alterations in cervical carcinomas” [22] as well as combined studies in COSMIC database nicely show the genetic heterogeneity that exists between patients with cervical carcinomas. Potential mechanisms for the release of cfDNA into the blood circulation are apoptosis and necrosis of cancer cells as well as secretion [23]. Since cfDNA can originate from both primary as well as metastatic tumor cells, it could serve as “a liquid biopsy” that reflects the genetic heterogeneity within a patient identifying putative targets for therapy. Moreover, plasma or serum circulating cfDNA also represents a way to monitor genetic heterogeneity during treatment and progression of the disease in a non-invasive manner, which may lead to personalized cancer care. Genomic characterization of cfDNA next to circulating tumor cells will provide a unique and non-invasive way to decide how to treat a patient at time of diagnosis as well as when patient becomes resistant to treatment and when the disease recurs. For these studies, it was proposed that the bio-banking is key.

Overview on Solid Biopsies (genomics), Biomarkers, and DNA Vaccines

In the field of translational research and precision medicine in cervical cancers, three possible options are presented for future developments: first, data from a randomized phase II trial conducted by Institut Curie [24] suggested that no tumor with a PI3K pathway mutation achieved a complete response to radio chemotherapy. Patients whose tumors had a PI3K pathway mutation in the Cetuximab treatment arm had a trend towards a poorer outcome, as compared to those with mutations having received standard treatment alone. The recent focus is now on an European Union (EU) funded program (RAIDs: rational assessment and innovative drug selection, http://www.raids-fp7.eu/) which focuses on discovery of specific mutational and pathway activation status in a large patient cohort. Second, HPV is associated with >90% of cervical cancers. In order to achieve a successful and controlled immunotherapy against E6 and E7 proteins of HPV, there is a need for endogenous or exogenous tumor antigens, for an immune system, which remains actionable towards T cell (effector) activity by checkpoint blockade inhibitors in a favorable tumor microenvironment [25]. Lastly, several lines of evidence suggest that inflammatory macrophages in the tumor microenvironment are phenotypically and functionally different from tissue resident macrophages and that inflammatory macrophages may need targeting for successful vaccination strategies [24].

PI3K Pathway/PIK3CA Mutational Status in cervical cancer

PI3K is a hetero-dimeric protein, including a 110-kDa catalytic subunit encoded by PIK3CA, which is often mutated in human cancer. PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway status and its inhibition may have important prognostic and therapeutic relevance in the management of patients with cervical cancer, given potential impact on chemotherapy and radiation resistance. PIK3CA mutation status has been evaluated in patients with metastatic or recurrent cancer who participated in PI3K/AKT/mTOR trials [26]. Overall, PIK3CA mutation rate was highest in squamous cell cervical cancers (36%), and patients with PIK3CA mutant tumors treated with PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors had overall higher ORR (40%). The impact of PIK3CA and clinical outcome has also been investigated in patients treated with radical chemoradiation with curative intent [29]. PIK3CA mutation was identified in 23% of patient tumors with 84% seen in squamous cell cancers. Importantly, PIK3CA status was independently associated with risk of death in patients with FIGO stage I/II disease and PIK3CA mutation increased risk of death 6-fold versus wild-type tumors [28]. A follow-up analysis using next-generation sequencing (NGS) validation showed that PIK3CA mutational frequency (26%) and estimate of effect on OS increased [29]. Overall, there is biologic rationale for targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in patients with cervical cancer, supporting further investigation in a GCIG cooperative clinical trial setting.

CONSENSUS CONCLUSIONS

The meeting concluded by drawing together the conclusions of breakout sessions, which considered concepts for the most needed new trials.

-

Hypo-fractionation

-

Palliative;

10 Gy versus 5 Gy X 4 with the endpoint of one month patient reported outcome

-

Curative intent;

3 weeks versus 5 weeks EBRT or possible 2 versus 4 brachytherapy fractions

-

-

Fertility sparing surgery after NACT for bulky lesions

lymph node evaluation prior to NACT, the ideal chemotherapy regimen and optimal fertility-preserving surgery post NACT deserve study.

-

SLN mapping

qualifications of surgeons, infrastructure, and pathology to perform careful ultrastaging, standardization of the procedure, and safety/stopping rules are key.

-

Adding the advancements of bevacizumab in advanced disease

Targeted therapies (especially PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway)

Combinations (VEGF-R and other angiogeneic GF-R )

-

Maintenance among high risk patients treated with CCRT (multiple positive pelvic nodes, corpus extension, and positive aortic nodes)

Emphasizing immunotherapy (vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors)

CONCLUSIONS

This was a highly successful initiative, which brought together leading trials groups and some leading sites from low- and middle-income countries. There was enthusiasm for working together and developing a cervical cancer network of high-incidence centers under the GCIG banner. There was consensus reached about a number of trial concepts to take forward in early disease and advanced disease as well as address issues of particular importance to the low- and middle-income country sites. The ultimate success of this initiative will be the establishment of two or three international collaborative trials in cervical cancer within the next 2 to 3 years.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Daniele A. Sumner, BA for her assistance and Monica Bacon (GCIG) in editing the manuscript and excellent organizational support. The authors would also like to thank the Scientific Committee of the GCIG Cervical Cancer Brainstorming meeting in November 2014(as listed above).

The authors are solely responsible for the content and preparation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Previous presentation: Presented at the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) cervix cancer braistorming day, November 6, 2014, Melbourne, Australia.

Conflict of Interest

To be completed once all journal COIs are returned.

SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE:

S. Sagae (JGOG), B. Monk (GOG), D. Gaffney (RTOG), K. Narayan (ANZGOG), S. Ryu (KGOG), M. McCormack (MRC-NCRI), A. Casado (EORTC-GCG), M. PLante (NCIC CTG), A. Reuss (AGO), A. Chavez (GICOM), E. Pujade-Lauraine (GINECO), W. Small (RTOG), M. Bacon (GCIG)

SPEAKERS:

BH. Nam (KGOG), A. Jhingran (RTOG), S. Temkin (NCI US), L. Mileshkin (ANZGOG), S. Scholl (EORTC-GCG), C. Doll (NCIC CTG), N. AbuRustum (G-GOC), F. Lecuru (GINECO), E. Berns (EORTC-GCG), H. Kitchener (MRC-NCRI)

PARTICIPANTS ( in alphabetical order of trial group):

M. Bookman (ACRIN), K. Tsuneda (ACRIN), G. Bognar (AGO Au), C. Boubenizek (AGO Au), J. Pfisterer (AGO De), A. Reuss (AGO De), S. Mahner (AGO De), V. Arora (ANZGOG), A. Hamilton (ANZGOG), J. Berek (COGi), A. Powell (COGi), R. Bekkers (DGOG), C. Creutzberg (DGOG), A. Fagotti (EORTC-GCG), J. Kim (EORTC-GCG), A. Poveda (GEICO), S. Nagao (GEICO), D. Gallardo (GICOM), A. Duenas (GICOM), A. Hardy (GINECO), I. Ray-Coquard (GINECO), P. Ramirez (G-GOC), K. Schmeler (G-GOC), W. Koh (GOG), K. Tewari (GOG), K. Fujiwara (GOTIC), Y. Takei (GOTIC), M. Mandai (ICORG), R. Coleman (ICORG), M. Mikami (JGOG), T. Toita (JGOG), JW. Kim (KGOG), BG. Kim (KGOG), N. Colombo (MaNGO), D. Katsaros (MaNGO), S. Greggi (MITO), G. Scambia (MITO), A. Taylor (MRC-NCRI), C. Fotopoulou (MRC-NCRI), H. Hirte (NCIC CTG), D. Provencher (NCIC CTG), J. Sehouli (NOGGO), M. Keller (NOGGO), J. Maenpaa (NSGO), M. Mirza (NSGO), A. Oza (PMHC), H. MacKay (PMHC), P. Eifel (RTOG), A. Russel (RTOG), D. Millan (SGCTG), A. Sadozye (SGCTG), E. Kohn (NCI-US), S. Temkin (NCI-US), M. Seckl (ISSTD), G. Elser (ENGOT)

HARMONIZATION: J. Martyn (ANZGOG), E. Aotani (JGOG), T. Hamano (GOTIC).

GCIG EXEC: M. Quinn (ANZGOG), G. Stuart (NCIC CTG)

INTERNATIONAL: S. Wilailak (THAILAND), P. Reis (BRAZIL), T. Linh (VIET NAM), S. Khatun (BANGLADESH), G. Giornelli (ARGENTINA), J. Kreynina (RUSSIA), H. van der Merwe (S. AFRICA), C. Huang (SINGAPORE), N. Bhatla (INDIA), A. Rodrigues (LACOG-INCA), R. Correa (CHILE), O. Rosengarten (ISRAEL)

GCIG INDUSTRY PARTNER representatives: M. Prahladan (AstraZeneca), S. Springer (Electa-Nucletron), N. Badri (Pharmamar), D. Bollag (Roche), H. Kato (Zeria)

Contributor Information

Satoru Sagae, Gynecologic Oncology, Sapporo West Kojinkai Clinic, Sapporo, Japan and JGOG and Chair, GCIG Cervix Cancer Committee.

Bradley J. Monk, University of Arizona Cancer Center-Phoenix, Creighton University School of Medicine at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ, USA and NRG Oncology-GOG and co-Chair GCIG Cervix Cancer Committee.

Eric Pujade-Lauraine, Hôtel-Dieu, AP-HP, Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France and GINECO and past-Chair GCIG.

David K Gaffney, Radiation Oncology, Huntsman Cancer Hospital, University of Utah, USA and RTOG and Chair, GCIG CCRN.

Kailash Narayan, Radiation Oncology, Peter Maccallum Cancer Centre and University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and ANZGOG.

Sang Young Ryu, Department of Surgery, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea and TACO Chair and KGOG.

Mary McCormack, Department of Oncology, University College Hospital London, London, UK and INTERLACE Chair and MRC NCRI.

Marie Plante, Gynecologic Oncology, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec, Quebec, Canada, and SHAPE Chair and NCIC CTG.

Antonio Casado, Department of Medical Oncology, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain and past-Chair EORTC GCG.

Alexander Reuss, Coordinating Center for Clinical Trials of the Phipps-University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany and co-Chair GCIG Stats and AGO-Ovar

Adriana Chávez-Blanco, GICOM Grupo Mexicano de Investigación en Cáncer de Ovario y Tumores Ginecológicos, A.C. México City, México and GCIG Harmonization (Ops).

Henry Kitchener, Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Manchester, St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester, UK and MRC NCRI and past-Chair GCIG and CCRN.

Byung-Ho Nam, Biotechnology Research Division, National Fisheries Research and Development Institute, Busan, Republic of Korea and KGOG and Chair GCIG Harmonization (Stats).

Anuja Jhingran, Radiation Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA and RTOG.

Sarah Temkin, Community Oncology and Prevention Trials Research Group (COPTRG), Division of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, USA and NCI US.

Linda Mileshkin, Radiation Oncology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Melbourne, Australia and OUTBACK Chair and chair ANZGOG.

Els Berns, Department of Medical Oncology, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, the Netherlands and EORTC CGC and DGOG.

Suzy Scholl, Médecin - Spécialiste en Oncologie, Institut Curie, Paris, France and EORTC GCG and Coordinator of RAIDs.

Corinne Doll, Department Oncology, Division of Radiation Oncology, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada and NCIC CTG.

Nadeem Abu-Rustum, Gynecology Service, Department of Surgery, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA and G-GOC.

Fabrice Lecuru, Chirurgie Cancérologique Gynécologique et du Sein, Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France and GINECO.

William Small, Jr, Department of Radiation Oncology, Stritch School of Medicine Loyola University, Chicago, IL, USA and RTOG and Chair GCIG.

References

- 1.Temple R. A regulatory authority’s opinion about surrogate endpoints. In: Nimmo W, Tucker G, editors. Clinical measurement in drug evaluation. West Sussex, England: Wiley; 1995. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vercellino GF, Piek JM, Schneider A, et al. Laparoscopic lymph node dissection should be performed before fertility preserving treatment of patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plante M. Bulky Early-Stage Cervical Cancer (2–4 cm Lesions): Upfront Radical Trachelectomy or Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Followed by Fertility-Preserving Surgery: Which Is the Best Option? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25:722–728. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levenback C, Ali S, Coleman R, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in women with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3786–3791. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lecuru F, Mathevet P, Querleu D, et al. Bilateral Negative Sentinel Nodes Accurately Predict Absence of Lymph Node Metastasis in Early Cervical Cancer: Results of The SENTICOL Study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1686–1691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cormier B, Diaz J, Shih K, et al. Establishing a sentinel lymph node mapping algorithm for the treatment of early cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohri N, Shen X, Dicker AP, et al. Radiotherapy Protocol Deviations and Clinical Outcomes: A Meta-analysis of Cooperative Group Clinical Trial. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2013;105:387–393. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glickman SW, McHutchison JG, Peterson ED, et al. Ethical and Scientific Implications of the Globalization of Clinical Research. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:816–823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb0803929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Søreide K, Alderson D, Bergenfelz A, et al. Strategies to improve clinical research in surgery through international collaboration. Lancet. 2013;382:1140–1151. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitchener HC, Hoskins W, Small W, Jr, et al. The development of priority cervical cancer trials a gynecologic cancer intergroup report. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:1092–1100. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181e730aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conley BA, Doroshow JH. Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice: NCI MATCH. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:297–299. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tewari KS, Sill MW, Long HJ, 3rd, et al. Improved Survival with Bevacizumab in Advanced Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:734–743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monk BJ, Sill MW, McMeekin DS, et al. Phase III trial of four cisplatin-containing doublet combinations in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4649–4655. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.8909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitagawa R, Katsumata N, Shibata T, et al. Paclitaxel Plus Carboplatin Versus Paclitaxel Plus Cisplatin in Metastatic or Recurrent Cervical Cancer: The Open-Label Randomized Phase III Trial JCOG0505. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2129–2135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monk BJ, Mas Lopez L, Zarba JJ, et al. Phase II, open-label study of pazopanib or lapatinib monotherapy compared with pazopanib plus lapatinib combination therapy in patients with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3562–3569. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Symonds P, Gourley C, Davidson S, et al. CIRCCa: A randomised double blind phase II trial of carboplatin-paclitaxel plus cediranib versus carboplatin-paclitaxel plus placebo in metastatic/recurrent cervical cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(suppl 4):abstr LBA25 PR. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00220-X. CRUK Grant Ref: C1256/A11416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camidge DR, Bang YJ, Kwak EL, et al. Activity and safety of crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: updated results from a phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1011–1019. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70344-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385–2394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167–2177. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim ES, Herbst RS, Wistuba II, et al. The BATTLE trial: personalizing therapy for lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:44–53. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-10-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright AA, Howitt BE, Myers AP, et al. Oncogenic mutations in cervical cancer: genomic differences between adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the cervix. Cancer. 2013;119:3776–3783. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ojesina AI, Lichtenstein L, Freeman SS, et al. Landscape of genomic alterations in cervical carcinomas. Nature. 2014;506:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature12881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarzenbach H, Hoon DS, Pantel K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:426–437. doi: 10.1038/nrc3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de la Rochefordiere A, Kamal M, Floquet A, et al. PIK3CA pathway mutations predictive of poor response following Standard radio chemotherapy +/− Cetuximab in cervical cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2530–2537. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellstedt H, Gaudernack G, Gerritsen WR, et al. Awareness and understanding of cancer immunotherapy in Europe. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:1828–1835. doi: 10.4161/hv.28943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franklin RA, Liao W, Sarkar A, et al. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science. 2014;344:921–925. doi: 10.1126/science.1252510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janku F, Wheler JJ, Naing A, et al. PIK3CA mutations in advanced cancers: characteristics and outcomes. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1568–1575. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntyre JB, Wu JS, Craighead PS, et al. PIK3CA mutational status and overall survival in patients with cervical cancer treated with radical chemoradiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McIntyre J, Kornaga E, Chan A, et al. Next generation sequencing validation of PIK3CA mutational status in cervical cancer patients treated with radical chemoradiotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(suppl 4):abstr 0710. [Google Scholar]