Abstract

Global profiling of metabolites in biological samples by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry results in datasets too large to evaluate manually. Fortunately, a variety of software programs are now available to automate the data analysis. Selection of the appropriate processing solution is dependent upon experimental design. Most metabolomic studies a decade ago had a relatively simple experimental design in which the intensities of compounds were compared between only two sample groups. More recently, however, increasingly sophisticated applications have been pursued. Examples include comparing compound intensities between multiple sample groups and unbiasedly tracking the fate of specific isotopic labels. The latter types of applications have necessitated the development of new software programs, which have introduced additional functionalities that facilitate data analysis. The objective of this review is to provide an overview of the freely available bioinformatic solutions that are either based upon or are compatible with the algorithms in XCMS, which we broadly refer to here as the “XCMS family” of software. These include CAMERA, credentialing, Warpgroup, metaXCMS, X13CMS, and XCMS Online. Together, these informatic technologies can accommodate most cutting-edge metabolomic applications and offer some advantages when compared to the original XCMS program.

Introduction

Data from liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS)-based untargeted metabolomic experiments are highly complex. Therefore, bioinformatic software is typically required for processing of the results. At this time, there are many reliable software solutions available.[1-9] It is not the purpose of this review to comprehensively detail each, nor is it our intent to provide any type of comparative evaluation. Rather, we will exclusively focus on a selection of freely available software solutions which are interoperable with the XCMS program. Some of these software solutions bear variants of the XCMS name, while others do not. We broadly refer to the class as a whole as the “XCMS family”.

Defining the Needs: A General Bioinformatic Workflow

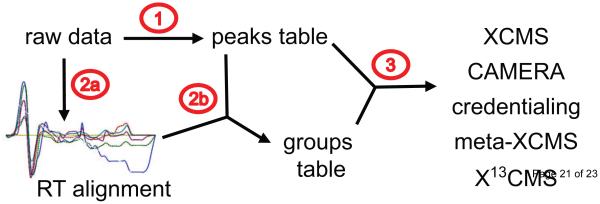

Historically, the bioinformatic workflow for processing untargeted metabolomic data has involved three general steps: feature detection, correspondence determination, and context-dependent analysis of the resulting measured values (Figure 1 and Figure 2).[10,11] Each is briefly outlined below.

Figure 1.

The bioinformatic workflow for processing untargeted metabolomic data with XCMS. The workflow has three general steps: 1. Feature detection, 2. Correspondence determination, and 3. Additional context-dependent analysis. These steps are numbered in red on the schematic. After acquisition of LC/MS profiling data, feature detection is performed on the raw data to generate a peaks table (step 1). Next, retention time drift is corrected (step 2a). The OBI-warp algorithm implemented within XCMS operates on the raw data to determine retention time drift. This produces a retention time correction map which, together with the peaks table, is used to establish correspondence and generate a groups table (step 2b). The peaks table and the groups table are the input for a variety of further analyses. The third step is dependent upon experimental objectives. In the standard XCMS analysis, step 3 is statistical analysis. The other programs listed use the peaks table and groups table to achieve different aims such as adduct and artifact annotation, multiple-factor analysis, and isotopic label tracking.

Figure 2.

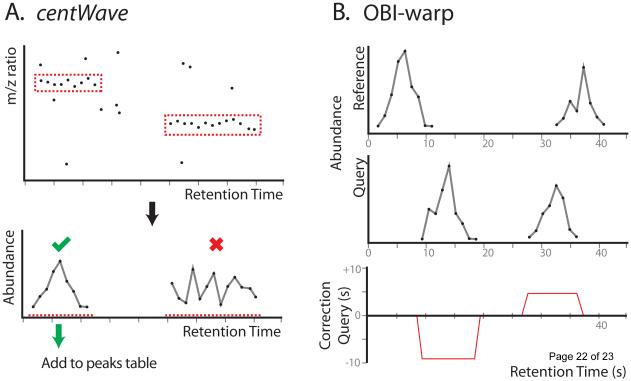

Schematic of the centWave and OBI-warp algorithms as implemented within XCMS. A. The first step in centWave is to find consecutive scans in which peaks are detected within a specific mass error (top). These are referred to as regions of interest (ROIs). Two such ROIs are displayed here and boxed in red. Next, extracted ion chromatograms are created for each ROI (bottom). Extracted ion chromatograms that display a peak shape are then added to the peaks table, as illustrated by the green checkmark and arrow. B. OBI-warp aligns a query sample to a reference sample. Here we illustrate a representative example in which two features are shifted in the query sample compared to the reference sample. Application of the correction curve to the query (bottom) brings the samples into alignment.

1. The first and perhaps most important step is feature detection (also known as peak detection or peak picking). The purpose of this step is to extract signals in the dataset that arise from real compounds, while attempting to exclude signals resulting from various noise sources.[12] Extracted signals with a unique mass-to-charge ratio and retention time are recorded as features. (Figure 2A)

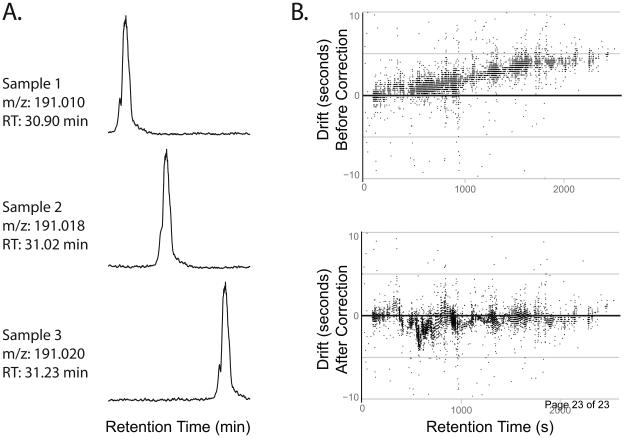

2. The second step in the workflow is establishing correspondence between the features detected from different sample runs. Correspondence refers to establishing which features from different analytical runs “correspond” to the same analyte. Establishing correspondence is arguably the most challenging step in the processing of untargeted metabolomic data.[11] Although the same analyte may be detected in multiple experimental runs, the measured mass-to-charge ratio and retention time of the analyte can vary in each run due to factors such as temperature fluctuation and column degradation (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Illustrating the correspondence problem. A. Extracted ion chromatograms of citrate from three samples show that its retention time and its measured mass-to-charge values vary between three samples run back to back. B. Uncorrected retention time drift of all features detected in sample 2 as compared to sample 1 (top). Uncorrected drift remaining after OBI-warp correction. (bottom). Note that though correction reduced the overall drift, there is no global correction which will perfectly align all peaks due to multiple, compound-specific drifts occurring at a single retention time.

In practice, the majority of investigators performing LC/MS-based metabolomics currently assert correspondence by aligning the time domains of each run with time-warping techniques. (Figure 2B) The objective is to correct for drift factors so that features can be grouped between samples by direct matching of retention time. Although the alignment approach for establishing correspondence has enabled many laboratories to successfully analyze untargeted metabolomic data, many drift factors are compound specific and therefore global-alignment techniques only reduce the total drift but do not eliminate it (Figure 3B). Accordingly, there remains a great need for robust correspondence determination algorithms and this is an active area of research interest.[11]

3. The last step of the workflow is context dependent. Analyses diverge, depending on experimental goals. In the simple cases when the objective is to compare sample classes, this step amounts to performing statistical analysis on the intensities of detected features. For more advanced objectives such as isotope tracing or tandem mass spectral analysis, additional algorithms are required.

Introducing XCMS

In 2006, the XCMS software was published as one of the first programs to provide a complete solution to the bioinformatic workflow outlined above for processing untargeted metabolomic data.[13] The “X” in the XCMS acronym is used to denote that the software can be applied to any form of chromatography. To date, however, XCMS has been mostly used to process LC/MS-based metabolomic data. The original XCMS software used the matchedFilter algorithm to accomplish feature detection, the retcor.peakgroups algorithm to perform alignment (an application of LOESS regression to well-behaved peak groups), and the group.density algorithm to group aligned features across samples on the basis of m/z bins. In recent years, a new algorithm for feature detection called centWave and a new algorithm for alignment called OBI-warp have been implemented within XCMS (Figure 2).[14,15] It is worth noting that while these algorithms have led to better overall XCMS performance, there is still great opportunity for improvement. It is exciting to consider, for example, that there are hundreds of published algorithms for peak detection and correspondence determination which have not yet been implemented within XCMS for comparative evaluation.[11,16]

Applying the centWave, OBI-warp, and group.density algorithms within XCMS results in what are known as the peaks table and the groups table (Figure 1). In the standard application of XCMS, the peaks table and the groups table are then used to create a diffreport. The diffreport provides statistics on feature groups that have altered intensities between sample groups.[17] When the original XCMS software was published in 2006, generating such a diffreport in the programming language R was considered cutting edge. From the diffreport, investigators can count the number of features detected from a sample to crudely compare metabolomic workflows.[18,19] More importantly, researchers can use the determined p-values and fold changes to find features with statistically significant changes in intensity between two sample groups. However, the XCMS diffreport also has some serious limitations. It does not provide metabolite identifications, which generally require matching tandem mass spectra from the research sample to the tandem mass spectra of authentic standards.[20] Additionally, the diffreport does not provide a reliable approximation of metabolites detected due to adducts, isotopes, fragments, and artifacts.[21,22] Indeed, depending on experimental conditions, more than 50% of the features on a diffreport can be a result of fragments and artifacts.[23] As the field of metabolomics has evolved over the last decade, there has been a major push to better annotate the XCMS diffreport. Multiple bioinformatic strategies which are interoperable with the XCMS program have now emerged that enable identification of adducts, isotopes, artifacts, and in some cases even structures.[24] A selection of these resources is detailed in the sections that follow.

Also note that the XCMS diffreport was designed for evaluating features with altered intensities between only two sample classes. Yet, there are a growing number of applications with more sophisticated experimental designs involving multifactorial analysis and stable isotope labeling. These types of applications require that step 3 of the bioinformatic workflow shown in Figure 1 diverge from that of the standard XCMS program. Thus, new software solutions have been developed that operate on the peaks table and the groups table with unique algorithms. Examples will be highlighted below.

A Clarification on Terminology

As multiple programs have emerged with variants of the XCMS name, it may be confusing for new investigators to distinguish which software is appropriate to use for specific applications. As an example, XCMS2 was the first program to be related in name to the original XCMS software.[25] Sometimes the program’s name is written as XCMS2, which may suggest that it implements a new generation of algorithms for the core functionalities of XCMS. However, XCMS2 only differs from XCMS in its ability to process tandem mass spectral data. We will not discuss XCMS2 further in this review. Processing of tandem mass spectral data will be covered in our discussion of XCMS Online.

Below, we highlight software programs which are interoperable with XCMS and provide key solutions to some common challenges in untargeted metabolomics. Most of these programs use the XCMS peaks table and/or groups table as their inputs. Therefore, collectively, we refer to them as the XCMS family of software.

CAMERA: Annotating Isotopologues, Adducts, Clusters, and Fragments

When a metabolite is analyzed by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), it is usually detected as more than a single ion species in the same mass spectrum due to the presence of isotopologues, adducts, clusters, and in-source fragments.[26] Because these ion species have different mass-to-charge values, XCMS reports each as a unique feature.[27] This increases the complexity of the XCMS diffreport and complicates statistical analysis as well as compound identification.

Given that adducts, clusters, and fragments are generally formed at the source in ESI-MS, they share the same retention time as the parent compound. Similarly, isotopes usually do not influence retention.[28] Thus, a strategy widely employed to group these types of related features is evaluation of chromatographic peak shape similarity.[29] The approach has been used by several software programs, but here we describe CAMERA because it was designed for postprocessing of the XCMS output.[28] Like XCMS, CAMERA is freely available from the Bioconductor repository.

In addition to grouping related features, CAMERA also attempts to annotate ion species by applying a rule table. The rule table works for identifying isotopes, frequent adducts such as sodium and chloride, and common neutral losses or cluster-ions. Users also have the option to combine LC/MS data from positive and negative modes to improve the reliability of ion annotations.

Credentialing: Annotating Artifacts

In a conventional LC/MS-based metabolomic experiment, the XCMS diffreport includes a large number of “artifactual” features. These features significantly complicate interpretation of the data because they are not directly associated with the sample but rather arise from contaminants introduced during analysis or from chemical noise, bioinformatic noise, etc.[21] Unfortunately, information in the XCMS diffreport is insufficient to discriminate artifactual features from biological features. Artifacts are particularly problematic when attempting to interpret metabolomic data at the comprehensive level. When evaluating different analytical methods to compare metabolome coverage, for example, it has been demonstrated that higher feature numbers do not necessarily correlate with more detected metabolites.[21] In part, this is because artifacts are highly variable and change as a function of extraction procedure, separation technology, mobile phase, instrumentation, and mass spectrometer settings.

Currently, approaches to identify artifacts in metabolomic data rely upon stable isotopes.[21,22] While these strategies have proven effective, we should point out that their application is limited to samples which can be cultured with labels (clinical specimens remain a challenge). One approach for removing artifacts, known as credentialing, was designed to be interoperable with the XCMS software.[21] In the credentialing scheme, artifactual features are distinguished by growing cells on heavy isotopic carbon and mixing them with natural-abundance samples at defined ratios. Notably, only features of cellular origin will have appropriate isotopic partners at the appropriate ratios. Thus, without structurally identifying every feature, artifacts can be filtered from the dataset computationally by using the credentialing software algorithms. With this platform, the number of “credentialed features” can be used (instead of total features) as a more reliable metric to benchmark analytical performance.

Warpgroup: Improving Quantitation with Consensus Integration Bounds

The standard XCMS workflow employs the centWave and group.density algorithms to detect peaks in each sample independently. In this scheme, the information used to group peaks is only the average m/z and retention time from all samples analyzed. Further, as each sample’s raw data are treated in isolation, differences in integration regions between samples contribute to increased variance in the processed dataset. Warpgroup is an XCMS compatible package that addresses these limitations with consensus integration bound analysis.[30] Warpgroup applies dynamic time warping and graph analysis to improve the precision of metabolomic data processing. Warpgroup improvements include: correspondence determination that leverages the local extracted ion chromatogram topography; detection and grouping of peak subregions; selection of similar integration bounds for each group; intelligent missing value filling; and reporting of several parameters which allow the filtering of bioinformatic noise.

The benefits of Warpgroup are due to the retrospective combination of several independent rounds of peak detection. For an E. coli dataset, as an example, application of Warpgroup resulted in an increase in the number of unique detected analytes by 26% and halved the mean coefficient of variation of all analytes (compared to the XCMS algorithms alone).[30] Warpgroup is implemented in a general manner and is applicable to all time series data, including metabolomic data from other software packages.

metaXCMS: Finding Shared Alterations Among Multiple Sample Classes

The original XCMS algorithms were designed to compare the intensities of features from only two sample groups. The challenge of applying simple pairwise comparisons is that knocking out a single protein can lead to hundreds or thousands of changes in feature intensities due to the interconnectivity of related pathways.[31] For instance, knocking out a protein may decrease the product of that protein. However, decreased levels of the protein’s product may then itself lead to a cascade of other context-dependent metabolic alterations. Determining which metabolites are altered directly as a result of knocking out a protein from those that are altered indirectly is challenging. Thus, it has become increasingly common in metabolomics to look for dysregulation shared among multiple sample groups as a strategy for data reduction. metaXCMS enables such multiple-factor comparisons by operating on XCMS diffreports.[32,33]

The power of assessing shared metabolic differences among multiple sample groups is perhaps best demonstrated by example. When control C. elegans worms were compared to long-lived C. elegans worms in which the germ line had been removed by glp-1 mutation, ~44% of the total detected features (13639) were altered with a p-value <0.05 and a fold change >2.[34] From these data alone, features directly associated with increased life span could not be distinguished from those features that were altered from glp-1 mutation but that did not affect life span. Because germ line induced extensions in life span are dependent upon the FOXO transcription factor DAF-16, double mutant daf-16;glp-1 worms are short lived. Thus, a comparison of long-lived glp-1 worms to both wildtype worms and short-lived daf-16;glp-1 worms with metaXCMS revealed shared features that were uniquely altered in glp-1 induced longevity. By performing similar analyses of other long-lived worms with metaXCMS, the number of detected features directly associated with longevity was ultimately reduced to six.[34]

X13CMS: Unbiased Mapping of Isotopic Fates

Although the intensities of thousands of features are measured by LC/MS-based untargeted metabolomics, these data provide only a static snapshot of cellular metabolism and do not generally capture the complex dynamics of biochemical pathways.[35] To quantitate metabolic fluxes and to determine the contribution of specific nutrients to metabolite/macromolecular synthesis, investigators typically use isotope-labeled tracers.[36] A number of robust approaches, such as metabolic flux analysis, are well established for these types of studies.[1] Most of the approaches use mass spectrometry or NMR to measure isotopic labeling in a targeted set of compounds.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest to integrate untargeted metabolomic technologies with stable isotopic tracers. One potential advantage of such an experimental design is the unbiased and comprehensive tracking of metabolite fates.[37,38] By following the metabolism of a labeled compound fed to a biological system comprehensively as a function of time by using LC/MS-based metabolomic approaches, new metabolite transformations may be discovered. Additionally, by comparing labeling patterns between different phenotypes using global metabolomic technologies, it is possible to identify relative changes in flux distributions.[39]

The original XCMS software was not designed to support experiments involving isotopic labels. Although analysis of isotopic labels can be accomplished by using XCMS together with CAMERA, the X13CMS software was recently developed specifically to support experimental designs based on stable isotopes.[28,40] To use X13CMS, LC/MS data acquired from samples with and without isotopic label are first processed by XCMS. The XCMS results are then forwarded to X13CMS, which identifies isotopologue groups corresponding to isotopically labeled compounds. Grouping of isotopologues is performed without any a priori knowledge except input of isotopic label(s) used, instrument mass accuracy, and chromatographic drift tolerance. The labeling pattern of each compound determined to be isotopically enriched can be quantitatively compared from multiple sample groups by using the getIsoDiffReport algorithm implemented within X13CMS.

XCMS Online: Metabolomics on the Cloud

The bioinformatic resources discussed up to this point are distributed as R packages and operated through a command-line interface or customized scripts. One major advantage of this format is flexibility. Researchers can modify the XCMS algorithms to suit their own specific needs. The modular nature of the original XCMS software has made it interoperable with new generations of programs for untargeted metabolomics and enabled multiple research laboratories to improve upon the original XCMS algorithms.[14,15,41,42]

A limitation of distributing XCMS as an R package is that many users do not have the programming expertise to use a command-line interface. This can be particularly problematic for clinical and biological laboratories. In response to this issue, an intuitive graphical interface was developed to process untargeted metabolomic data which implements many of the algorithms described in this review including those in XCMS, CAMERA, metaXCMS, as well as others. The platform, called XCMS Online, is cloud based.[43] Investigators upload untargeted metabolomic data by simply dragging and dropping their files into the program. Parameters are then selected and processing occurs on the cloud. Researches receive an e-mail notifying them when processing is complete. Results can then be viewed online, or downloaded for later use. An advantage unique to XCMS Online is that data are directly searched against the METLIN metabolite database.[44] When users upload both MS and MS/MS data, the matching can be performed on the basis of accurate mass and fragmentation patterns.[24] Thus, within XCMS Online, features on the diffreport can be annotated as possible isotopes, adducts, or structures.

Concluding Remarks

There are many reliable bioinformatic solutions for processing untargeted metabolomic data. The XCMS software is one platform-agnostic solution which is widely used. The success of XCMS is related to it being open source and highly modular. This has enabled multiple laboratories to contribute to its development with algorithms such as centWave and OBI-warp. There are a multitude of additional algorithms available that are relevant to the processing of untargeted metabolomic data, and it is recommended that their potential to improve XCMS performance be evaluated in the future. Given that XCMS is open source and modular, it is also interoperable with new generations of metabolomic software implemented within R and aimed at achieving advanced functionalities (e.g., better annotation of features, multifactorial analysis, unbiased tracking of isotopic labels, etc.). Consequently, the core algorithms within XCMS have become an important piece of many bioinformatic pipelines. Hopefully the roadmap for these pipelines that we have provided here will be useful in helping researchers chose a software platform most compatible with their experimental objectives.

Highlights.

1.) XCMS implements four algorithms for processing metabolomic data.

2.) There are many published algorithms yet to be implemented or tested within XCMS.

3.) The major roles of XCMS are feature detection and correspondence determination.

4.) The XCMS peaks and groups tables are used by other programs with advanced functions.

Acknowledgements

GJP received financial support for this work from the National Institutes of Health Grants R01 ES022181 and L30 AG0 038036, as well as the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation, and the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Antoniewicz MR. Methods and advances in metabolic flux analysis: a mini-review. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;42:317–325. doi: 10.1007/s10295-015-1585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clasquin MF, Melamud E, Rabinowitz JD. LC-MS data processing with MAVEN: a metabolomic analysis and visualization engine. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2012 doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1411s37. Chapter 14:Unit14 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kastenmuller G, Romisch-Margl W, Wagele B, Altmaier E, Suhre K. metaP-server: a web-based metabolomics data analysis tool. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/839862. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katajamaa M, Oresic M. Processing methods for differential analysis of LC/MS profile data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lommen A, Kools HJ. MetAlign 3.0: performance enhancement by efficient use of advances in computer hardware. Metabolomics. 2012;8:719–726. doi: 10.1007/s11306-011-0369-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melamud E, Vastag L, Rabinowitz JD. Metabolomic analysis and visualization engine for LC-MS data. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9818–9826. doi: 10.1021/ac1021166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsugawa H, Cajka T, Kind T, Ma Y, Higgins B, Ikeda K, Kanazawa M, VanderGheynst J, Fiehn O, Arita M. MS-DIAL: data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat Methods. 2015;12:523–526. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uppal K, Soltow QA, Strobel FH, Pittard WS, Gernert KM, Yu T, Jones DP. xMSanalyzer: automated pipeline for improved feature detection and downstream analysis of large-scale, non-targeted metabolomics data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xia J, Sinelnikov IV, Han B, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst 3.0-making metabolomics more meaningful. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:W251–257. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yore MM, Syed I, Moraes-Vieira PM, Zhang T, Herman MA, Homan EA, Patel RT, Lee J, Chen S, Peroni OD, et al. Discovery of a class of endogenous mammalian lipids with anti-diabetic and anti-inflammatory effects. Cell. 2014;159:318–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith R, Ventura D, Prince JT. LC-MS alignment in theory and practice: a comprehensive algorithmic review. Brief Bioinform. 2015;16:104–117. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbt080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rafiei A, Sleno L. Comparison of peak-picking workflows for untargeted liquid chromatography/high-resolution mass spectrometry metabolomics data analysis. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2015;29:119–127. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith CA, Want EJ, O'Maille G, Abagyan R, Siuzdak G. XCMS: processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Anal Chem. 2006;78:779–787. doi: 10.1021/ac051437y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tautenhahn R, Bottcher C, Neumann S. Highly sensitive feature detection for high resolution LC/MS. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:504. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prince JT, Marcotte EM. Chromatographic alignment of ESI-LC-MS proteomics data sets by ordered bijective interpolated warping. Anal Chem. 2006;78:6140–6152. doi: 10.1021/ac0605344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trevino V, Yanez-Garza IL, Rodriguez-Lopez CE, Urrea-Lopez R, Garza-Rodriguez ML, Barrera-Saldana HA, Tamez-Pena JG, Winkler R, Diaz de-la-Garza RI. GridMass: a fast two-dimensional feature detection method for LC/MS. J Mass Spectrom. 2015;50:165–174. doi: 10.1002/jms.3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gowda H, Ivanisevic J, Johnson CH, Kurczy ME, Benton HP, Rinehart D, Nguyen T, Ray J, Kuehl J, Arevalo B, et al. Interactive XCMS Online: simplifying advanced metabolomic data processing and subsequent statistical analyses. Anal Chem. 2014;86:6931–6939. doi: 10.1021/ac500734c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masson P, Alves AC, Ebbels TM, Nicholson JK, Want EJ. Optimization and evaluation of metabolite extraction protocols for untargeted metabolic profiling of liver samples by UPLC-MS. Anal Chem. 2010;82:7779–7786. doi: 10.1021/ac101722e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanes O, Tautenhahn R, Patti GJ, Siuzdak G. Expanding coverage of the metabolome for global metabolite profiling. Anal Chem. 2011;83:2152–2161. doi: 10.1021/ac102981k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu ZJ, Schultz AW, Wang J, Johnson CH, Yannone SM, Patti GJ, Siuzdak G. Liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry characterization of metabolites guided by the METLIN database. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:451–460. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahieu NG, Huang X, Chen YJ, Patti GJ. Credentialing features: a platform to benchmark and optimize untargeted metabolomic methods. Anal Chem. 2014;86:9583–9589. doi: 10.1021/ac503092d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stupp GS, Clendinen CS, Ajredini R, Szewc MA, Garrett T, Menger RF, Yost RA, Beecher C, Edison AS. Isotopic ratio outlier analysis global metabolomics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Anal Chem. 2013;85:11858–11865. doi: 10.1021/ac4025413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zamboni N, Saghatelian A, Patti GJ. Defining the metabolome: size, flux, and regulation. Mol Cell. 2015;58:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benton HP, Ivanisevic J, Mahieu NG, Kurczy ME, Johnson CH, Franco L, Rinehart D, Valentine E, Gowda H, Ubhi BK, et al. Autonomous metabolomics for rapid metabolite identification in global profiling. Anal Chem. 2015;87:884–891. doi: 10.1021/ac5025649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benton HP, Wong DM, Trauger SA, Siuzdak G. XCMS2: processing tandem mass spectrometry data for metabolite identification and structural characterization. Anal Chem. 2008;80:6382–6389. doi: 10.1021/ac800795f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keller BO, Sui J, Young AB, Whittal RM. Interferences and contaminants encountered in modern mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;627:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. Innovation: Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhl C, Tautenhahn R, Bottcher C, Larson TR, Neumann S. CAMERA: an integrated strategy for compound spectra extraction and annotation of liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry data sets. Anal Chem. 2012;84:283–289. doi: 10.1021/ac202450g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ipsen A, Want EJ, Lindon JC, Ebbels TM. A statistically rigorous test for the identification of parent-fragment pairs in LC-MS datasets. Anal Chem. 2010;82:1766–1778. doi: 10.1021/ac902361f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahieu NG, Spalding J, Patti GJ. Warpgroup: Increased Precision of Metabolomic Data Processing by Consensus Integration Bound Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patti GJ, Tautenhahn R, Johannsen D, Kalisiak E, Ravussin E, Bruning JC, Dillin A, Siuzdak G. Meta-analysis of global metabolomic data identifies metabolites associated with life-span extension. Metabolomics. 2014;10:737–743. doi: 10.1007/s11306-013-0608-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tautenhahn R, Patti GJ, Kalisiak E, Miyamoto T, Schmidt M, Lo FY, McBee J, Baliga NS, Siuzdak G. metaXCMS: second-order analysis of untargeted metabolomics data. Anal Chem. 2011;83:696–700. doi: 10.1021/ac102980g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patti GJ, Tautenhahn R, Siuzdak G. Meta-analysis of untargeted metabolomic data from multiple profiling experiments. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:508–516. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patti GJ, Tautenhahn R, Johannsen D, Kalisiak E, Ravussin E, Bruning JC, Dillin A, Siuzdak G. Meta-Analysis of Global Metabolomic Data Identifies Metabolites Associated with Life-Span Extension. Metabolomics. 2014;10:7. doi: 10.1007/s11306-013-0608-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeBerardinis RJ, Thompson CB. Cellular metabolism and disease: what do metabolic outliers teach us? Cell. 2012;148:1132–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buescher JM, Antoniewicz MR, Boros LG, Burgess SC, Brunengraber H, Clish CB, DeBerardinis RJ, Feron O, Frezza C, Ghesquiere B, et al. A roadmap for interpreting C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;34:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Creek DJ, Chokkathukalam A, Jankevics A, Burgess KE, Breitling R, Barrett MP. Stable isotope-assisted metabolomics for network-wide metabolic pathway elucidation. Anal Chem. 2012;84:8442–8447. doi: 10.1021/ac3018795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen YJ, Huang X, Mahieu NG, Cho K, Schaefer J, Patti GJ. Differential incorporation of glucose into biomass during Warburg metabolism. Biochemistry. 2014;53:4755–4757. doi: 10.1021/bi500763u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang L, Kim D, Liu X, Myers CR, Locasale JW. Estimating relative changes of metabolic fluxes. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10:e1003958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang X, Chen YJ, Cho K, Nikolskiy I, Crawford PA, Patti GJ. X13CMS: global tracking of isotopic labels in untargeted metabolomics. Anal Chem. 2014;86:1632–1639. doi: 10.1021/ac403384n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Creek DJ, Jankevics A, Burgess KE, Breitling R, Barrett MP. IDEOM: an Excel interface for analysis of LC-MS-based metabolomics data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1048–1049. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Libiseller G, Dvorzak M, Kleb U, Gander E, Eisenberg T, Madeo F, Neumann S, Trausinger G, Sinner F, Pieber T, et al. IPO: a tool for automated optimization of XCMS parameters. BMC Bioinformatics. 2015;16:118. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0562-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tautenhahn R, Patti GJ, Rinehart D, Siuzdak G. XCMS Online: a web-based platform to process untargeted metabolomic data. Anal Chem. 2012;84:5035–5039. doi: 10.1021/ac300698c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tautenhahn R, Cho K, Uritboonthai W, Zhu Z, Patti GJ, Siuzdak G. An accelerated workflow for untargeted metabolomics using the METLIN database. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:826–828. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]