Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Rhinoplasty continues to rank among the most popular cosmetic surgical treatments. Measuring what the nose looks like has typically involved the use of observer-reported or physician-reported outcome measures (eg, photographs). While objective outcomes are important, facial appearance is subjective, and asking patients what they think about the appearance of their nose is of paramount importance. The patient perspective can be measured using patient-reported outcome instruments.

OBJECTIVE

To describe the development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q scales and adverse effects checklist designed to measure rhinoplasty outcomes.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

A questionnaire was completed by patients recruited between July 13, 2010, and March 1, 2015. Psychometric methods were used to select the most clinically sensitive items for inclusion in item-reduced scales as well as to examine reliability, validity, and ability to detect clinical change. The setting was plastic surgery clinics in the United States, England, and Canada. Participants were preoperative and postoperative patients 18 years or older undergoing rhinoplasty.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES

Responses and validation measures of the FACE-Q scales and adverse effects checklist.

RESULTS

In total, 158 of 169 patients invited to participate in the study were enrolled (response rate, 93.5%). The most common adverse effect was the skin of the nose looking thick or swollen. Rasch measurement theory analysis led to the refinement of a 10-item Satisfaction With Nose Scale and a 5-item Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale. The person separation index and Cronbach α were 0.91 and 0.96, respectively, for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and 0.89 and 0.96, respectively, for the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale. All items had ordered thresholds and good item fit. Satisfaction with the nose and nostrils was incrementally lower in participants bothered by specific adverse effects (eg, the skin of the nose looking thick or swollen). Patient satisfaction on the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale and on 3 additional FACE-Q scales (ie, Satisfaction With Facial Appearance Scale, Psychological Function Scale, and Social Function Scale) was higher after surgery than before surgery (P < .001 for all, independent samples t test). Twenty-three participants who provided preoperative and postoperative data reported improvement on all 5 scales (P ≤ .003 for all). The effect sizes ranged from 0.6 to 2.3. Significant individual-level change was reported by most participants for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale, Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale, Satisfaction With Facial Appearance Scale, and Social Function Scale.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

A FACE-Q scales rhinoplasty module can be used in clinical practice, research, and quality improvement to incorporate the patient perspective in outcome assessments.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

NA.

Rhinoplasty continues to rank among the most popular surgical cosmetic treatments. In 2014, nose reshaping was the second most common surgical procedure performed in the United States (217 124 total operations), second only to breast augmentation.1 Rhinoplasty can change a person’s appearance dramatically. Measuring what the nose looks like—a fundamental and proximal measure of outcome—has typically involved the use of clinical outcome assessment tools such as observer-reported or physician-reported outcome measures (eg, ratings of preoperative and postoperative photographs). While objective outcomes are important, facial appearance is subjective, and asking patients what they think about the appearance of their nose is of paramount importance.

Typically, rhinoplasty studies examining patient-reported outcomes (PROs) have measured psychiatric or psychological issues,2–4 health-related quality of life,2,4–12 or nasal symptoms3,8,9,13–19 using a range of PRO instruments. However, a United Kingdom Department of Health systematic review of PRO measures for cosmetic surgery identified only 9 specific instruments that demonstrated adequate psychometric properties and were developed with patient input.20 The widely used Rhinoplasty Outcomes Evaluation questionnaire5 was excluded from the United Kingdom review because it was developed without patient input.20 The frequently used Derriford Appearance Scale,8 which is one of the 9 measures in the United Kingdom Department of Health review, does not measure specific rhinoplasty concerns. Therefore, to our knowledge, there is no patient-derived, scientifically sound PRO instrument available that can be used to measure how patients perceive the appearance of their nose. The FACE-Q 21–24 is a multimodular PRO instrument that includes more than 40 independently functioning scales and checklists. The FACE-Q scales measure outcomes that matter to patients, including facial appearance, quality of life, and adverse effects. In addition, the FACE-Q includes scales that measure the patient experience of care (eg, satisfaction with provided information). The FACE-Q was developed for use with surgical and nonsurgical facial aesthetic patients. The objective of this article is to describe the development and validation of the FACE-Q scales crafted specifically for measuring the appearance of the nose and adverse effects after rhinoplasty.

Methods

Study Design

Ethics review board approval was obtained before study initiation. The principal investigator (A.L.P.) obtained institutional review board approval through The New School in New York City. In the United Kingdom, local research and development approval (National Health Service permission) was obtained from University College London Hospitals National Health Service Foundation Trust. The FACE-Q was developed by following internationally recommended guidelines for the development of a new PRO instrument.25–28 The mixed-methods approach to develop and validate the FACE-Q scales is described in detail elsewhere.22–24 Briefly, a systematic review,29 interviews with 50 surgical or nonsurgical facial aesthetic patients (9 undergoing rhinoplasty), and input from 26 experts in the field were used to develop a conceptual framework and specific FACE-Q scales and checklists, which were further refined through cognitive interviews with 35 facial aesthetic patients (2 undergoing rhinoplasty).

For patients undergoing rhinoplasty, a set of 25 items that measure satisfaction with the appearance of the nose and nostrils was designed. Our aim in developing a large number of items was to make it possible to test alternative ways of asking about parts of the nose (eg, how the tip looks and how the tip looks when smiling or laughing), in addition to its characteristics (eg, size and shape and size and shape in profile). The goal was to identify and retain the best subset of items based on psychometric tests and clinical importance. Instructions for completing the 25 items asked respondents to answer with their facial appearance in mind and in relation to the past week. Four response options were provided for each item (ie, “very dissatisfied,” “somewhat dissatisfied,” “somewhat satisfied,” and “very satisfied”) in keeping with the best-practice guidelines for the optimal response option format.30

In addition to the appearance scale, a short checklist was designed to measure adverse effects (eg, “The skin of your nose looking thick or swollen?”). Instructions asked respondents to indicate how much in the past 2 days they have been bothered by each adverse effect. Four response options were provided (ie, “not at all,” “a little,” “moderately,” or “extremely”). In this article, for validation purposes, we also describe findings for 3 other FACE-Q scales that participants were asked to complete, including the 10-item Satisfaction With Facial Appearance Scale, 10-item Psychological Function Scale, and 8-item Social Function Scale. Previous publications23,24 supported these 3 FACE-Q scales as reliable, valid, and responsive measurement tools. Participants were also asked to answer questions that would allow us to characterize the sample, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and whether they had previously undergone a rhinoplasty. These questions were used to identify any items with differential item function (ie, the degree to which item performance remains stable across subgroups). The FACE-Q scales and adverse effects checklist were included in a questionnaire booklet that was completed by preoperative and postoperative patients 18 years or older undergoing rhinoplasty. Potential participants were provided with a letter explaining the study. Because this investigation was a questionnaire survey study, completion of the FACE-Q booklet implied informed consent.

In the United States, England, and Canada, patients undergoing rhinoplasty were recruited from 9 plastic surgery clinics. In 7 clinics in the United States, Canada, and England, patients were recruited when they checked in for an appointment. In the remaining 2 clinics in the United States and Canada, patients were invited to participate via a postal survey. The survey included a personalized letter from the relevant physician along with the FACE-Q booklet, with up to 3 reminders mailed as necessary. In England, all participants were preoperative patients. These participants were invited to provide an email if they were willing to complete the FACE-Q scales again 4 months after surgery. Those who agreed were sent a URL link to access and complete the FACE-Q scales directly into REDCap, a secure web-based application for electronic data capture.31 Recruitment took place between July 13, 2010, and March 1, 2015. The dates of our analysis were March 1, 2015, to August 12, 2015.

Analysis

The proportion of responses for each response option of the adverse effects checklist was computed. For appearance items, Rasch measurement theory (RMT)32,33 (a modern psychometric approach) was used for item reduction. Data were analyzed using available software (RUMM2030; RUMM Laboratory).34 Rasch measurement theory examines the difference between observed and predicted item responses to determine whether the data collected from a sample fits a mathematical model.35 To determine whether the data for a set of items fit the model, a range of statistical and graphical tests was examined. The evidence from these tests was considered together to make decisions about the overall quality of a scale.35–37 The following 6 tests and criteria were examined.

First were thresholds for item response options

We examined the 4 response options (“very dissatisfied,” “somewhat dissatisfied,” “somewhat satisfied,” and “very satisfied”) to determine if they worked as hypothesized (ie, that the response categories scored with successive integer scores imply a continuum that increases for the construct measured). Specifically, we examined the ordering of thresholds, which are points of crossover between adjacent response categories (eg, between “somewhat satisfied” and “very satisfied”).

Second were item fit statistics

A scale should map out a clinically important construct. We examined the following 3 indicators of fit to determine if the items of our scale work together as a set: (1) log residuals (item and person interaction), (2) χ2 values (item and trait interaction), and (3) item characteristic curves. Fit statistics should be interpreted together and in relation to clinical usefulness. The criteria for fit residuals should fall between −2.5 and 2.5. The χ2 value for each item should be nonsignificant after Bonferroni adjustment.

Third was dependency

Residual correlations between items in a scale can artificially inflate reliability. Residual correlations between items should be below 0.30 as a benchmark.33

Fourth was stability

We examined differential item function by age (18–20, 21–25, 26–30, 31–39, or ≥40 years), gender, race/ethnicity (recoded as white vs other), and country (United States, England, or Canada). χ2 Values that are significant after Bonferroni adjustment can indicate that an item has potential differential item function.

Fifth was targeting

The items of a scale need to be targeted to the patient population for which the scale was developed. Targeting can be examined by inspecting the spread of person (range of the construct as reported by the sample) and item (range of the construct as measured by the items in a scale) locations. Items in a scale should be evenly spread over a reasonable range and should match the range of the construct experienced by the sample.

Sixth was the person separation index (PSI)

We examined reliability using the PSI, which is comparable to Cronbach α33 in traditional test theory methods. The PSI measures error associated with the measurement of individuals in a sample. Higher values indicate greater reliability.

In addition to the RMT analysis, we examined scale reliability in terms of Cronbach α.38 Rasch logit scores for each participant were transformed to reflect scores that ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better outcomes. Using these scores, we examined construct validity by testing the following 4 hypotheses.

First, scores for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale would be incrementally lower for participants who report being bothered on the 4 adverse effects checklist items (“not at all,” “a little,” “moderately,” and “extremely”). For these analyses, we collapsed the categories into the following 3 because of the small sample size in the extreme,“ How much have you been bothered by” category: “not at all,” “a little,” and “moderately or extremely.”

Second, higher scores on the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale would correlate with higher scores on the Satisfaction With Facial Appearance Scale, Psychological Function Scale, and Social Function Scale. However, they would not correlate with patient characteristics (ie, age, gender, and race/ethnicity).

Third, the sample of preoperative patients would report lower scores on all 5 FACE-Q scales. The sample of postoperative patients would report higher scores.

Fourth, patient satisfaction with the nose and nostrils would be incrementally higher for those who report being more satisfied in response to the “How attractive your nose looks?” summary question. Response options were “very dissatisfied,” “somewhat dissatisfied,” “somewhat satisfied,” and “very satisfied.”

To examine responsiveness, we computed group-level and individual-level change for the 5 FACE-Q scales completed by the subgroup of participants who provided data before and after surgery. For group-level change, we compared preoperative and postoperative Rasch transformed scores using paired t test and then calculated an effect size38 (ie, the mean time 1 minus the mean time 2 divided by the standard deviation at time 1). Cohen criteria were used to interpret the results (0.2 is small, 0.5 is moderate, and 0.8 is large).39–42 For individual level change, we computed for each person the significance of his or her own change in measurement as follows: (1) the size of his or her change score (ie, the time 1 minus the time 2), (2) the standard error of the difference (ie, square root of the sum of the squared time 1 and time 2 standard error values), and (3) the significance of the change (ie, the change score divided by the standard error of the difference).43 The significance of the change values was used to categorize the sample into the following 5 groups to reflect the significance of each person’s change score: (1) significant improvement (significance of the change, at least 1.96), (2) nonsignificant improvement (significance of the change, >0 to 1.95), (3) no change (significance of the change, 0), (4) nonsignificant worsening (significance of the change −1.95 to <0), and (5) significant worsening (significance of the change, −1.96 or less).

Results

In total, 158 of 169 patients invited to participate in the study were enrolled (response rate, 93.5%). Twenty-three patients provided data before and after their rhinoplasty. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | Value (N = 158) |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Mean (SD) [range] | 32.6 (11.4) [18–70] |

| Missing, No. (%) | 5 (3.2) |

| Sex, No. (%) | |

| Female | 113 (71.5) |

| Male | 40 (25.3) |

| Missing | 5 (3.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, No. (%) | |

| White | 106 (67.1) |

| Other | 38 (24.1) |

| Missing | 14 (8.9) |

| Country, No. (%) | |

| United States | 91 (57.6) |

| England | 54 (34.2) |

| Canada | 13 (8.2) |

| Assessments, No. (%)a | |

| 1 Preoperative | 81 (51.3) |

| 1 Postoperative | 48 (30.4) |

| 2 Postoperative | 5 (3.2) |

| 4 Postoperative | 1 (0.6) |

| 1 Preoperative and 1 postoperative | 19 (12.0) |

| 1 Preoperative and 2 postoperative | 4 (2.5) |

Includes a total of 193 assessments (ie, completed scales) because some participants completed more than 1 questionnaire booklet.

The adverse effects checklist was completed by 77 postoperative participants, who provided a total of 84 assessments. Postoperative participants completed the FACE-Q a mean (SD) of 8.4(7.9) months (range, 0.5–36 months) after their rhinoplasty. Table 2 summarizes the number of postoperative participants who reported being bothered by the 4 postoperative adverse effects for each response option. The most common adverse effect, experienced by more than half of the sample, was “The skin of your nose looking thick or swollen?” For one adverse effect (“Tenderness [eg, when wearing sunglasses]?”), being bothered by the adverse effect was associated with the time since surgery. For example, the time in the “not at all” group was a mean (SD) of 10.6 (7.7) months after surgery, while the time in those bothered by the symptom was a mean (SD) of 5.6 (6.6) months after surgery (P = .004, independent samples t test). The RMT analysis of the 25 items was used to identify a subset of items that were included in 2 FACE-Q scales, the 10-item Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the 5-item Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale. The 10 items dropped during the item reduction process and the reasons why they were dropped are listed in the eTable in the Supplement. The 2 FACE-Q scales (Satisfaction With Nose Scale and Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale) are easy to comprehend (ie, the Flesch reading ease scores are 100%, and the Flesch-Kincaid grade levels are 0).44 Furthermore, 12 of the 15 items are below grade 1 (range, 0–3.0). The Flesch reading ease and the Flesch-Kincaid grade for the 4 items that form the adverse effects checklist are higher (62.1% and 6.2, respectively), which reflects the nature of the items that ask about postoperative surgical issues.

Table 2.

Adverse Effects Checklista

| “How Much Have You Been Bothered By” | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Not at All” | “A Little” | “Moderately” | “Extremely” | |

| “The skin of your nose looking thick or swollen?” (n = 83) | 38 (45.8) | 23 (27.7) | 17 (20.5) | 5 (6.0) |

| “Tenderness (eg, when wearing sunglasses)?” (n = 82) | 43 (52.4) | 26 (31.7) | 10 (12.2) | 3 (3.7) |

| “Difficulty breathing through your nose?” (n = 84) | 53 (63.1) | 19 (22.6) | 11 (13.1) | 1 (1.2) |

| “Unnatural-appearing bumps or hollows on your nose?” (n = 82) | 56 (68.3) | 12 (14.6) | 8 (9.8) | 6 (7.3) |

The adverse effects checklist was not completed in 5 postoperative assessments.

The RMT findings for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale supported their reliability and validity. All items for both scales had ordered thresholds, supporting the hypothesis that the successive integer scores worked as a continuum. Table 3 summarizes the item fit for the 15 items. Two items in the Satisfaction With Nose Scale (ie, “How straight your nose looks?” and “How your nose looks from every angle?”) had item fits marginally outside the −2.5 to 2.5 recommended range but were not significant in terms of the χ2 P values and thus were retained in the scale because of their clinical importance. Item residual correlations were below 0.30 for all items. There was no differential item function detected on any item for age, gender, race/ethnicity, or country. Further information about item performance (ie, item information curves) are shown in eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Table 3.

Rasch Measurement Theory Statistical Indicators of Fita

| Item | Location | SE | Fit Residual | χ2 Statistic | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction With Nose Scale | |||||

| “Width at the bottom?” | −0.74 | 0.12 | 1.26 | 7.27 | .03 |

| “Length?” | −0.71 | 0.12 | −0.28 | 0.21 | .90 |

| “Bridge?” | −0.34 | 0.13 | 1.26 | 1.25 | .54 |

| “Suits your face?” | −0.22 | 0.12 | −1.78 | 9.01 | .01 |

| “Straight?” | −0.11 | 0.11 | 3.22 | 9.92 | .007 |

| “Overall size?” | 0.01 | 0.13 | −0.80 | 6.48 | .04 |

| “Shape in profile?” | 0.34 | 0.12 | −0.44 | 2.80 | .25 |

| “Looks in photographs?” | 0.47 | 0.13 | −0.05 | 2.75 | .25 |

| “Tip?” | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 1.48 | .48 |

| “From every angle?” | 0.83 | 0.14 | −2.96 | 13.68 | .001 |

| Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale | |||||

| “Size?” | −0.45 | 0.18 | −2.15 | 2.25 | .32 |

| “Shape?” | −0.19 | 0.18 | −1.39 | 0.72 | .70 |

| “Nostril show?” | −0.16 | 0.18 | −0.26 | 0.32 | .85 |

| “Well matched?” | 0.10 | 0.17 | 1.95 | 3.75 | .15 |

| “Look overall?” | 0.70 | 0.18 | −1.10 | 1.23 | .54 |

Items are in serial order for each scale.

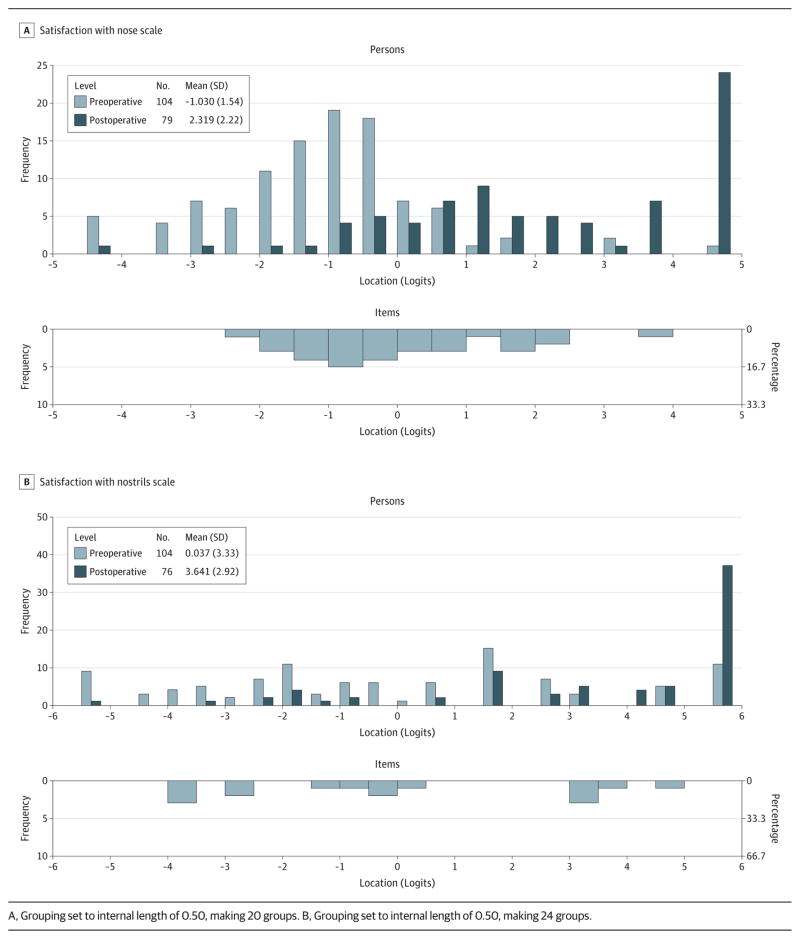

The scale-to-sample targeting is shown in the Figure, with the items (bottom histogram) mapping out the continuum for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale. Preoperative and postoperative patients (top histogram) are shown separately. The pattern of scores of preoperative patients (lower on the scale) is distinct from that of postoperative patients (higher on the scale). The results provide evidence that the 2 scales define a continuum for satisfaction with their appearance for preoperative and postoperative patients undergoing rhinoplasty. Of the 193 assessments, some (3.1%[6 of 192] on the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and 5.3%[10 of 189] on the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale) scored at the floor (ie, “very dissatisfied” on all items), and some (14.6% [28 of 192] on the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and 27.0%[51 of 189] on the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale) scored at the ceiling (ie, “very satisfied” on all items). Those scoring at the floor were primarily preoperative patients, while those scoring at the ceiling were primarily postoperative patients. eFigure 2 in the Supplement shows the scale-to-sample targeting for the sample for both scales and includes the test information curves. These curves show that the best point of measurement is at the center of the scale.

Figure.

Person-Item Threshold Distribution

In terms of reliability, the PSIs for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale were 0.91 and 0.89, respectively. Cronbach α levels for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale were higher at 0.96 and 0.96, respectively.

The difference in the mean score for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale was significant for 2 items from the adverse effects checklist specific to the appearance (ie, “The skin of your nose looking thick or swollen?” and “Unnatural-appearing bumps or hollows on your nose?”) (P ≤ .003, analysis of variance). In addition, for the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale, the mean scores by response category differed for the “Tenderness (eg, when wearing sunglasses)?” item (P = .03, analysis of variance).

Higher scores on the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale correlated with higher scores on the Satisfaction With Facial Appearance Scale (r = 0.81, P < .001 for the nose scale and r = 0.63, P < .001 for the nostrils scale), the Psychological Function Scale (r = 0.62, P < .001 for the nose scale and r = 0.54, P < .001 for the nostrils scale), and the Social Function Scale (r = 0.43, P < .001 for the nose scale and r = 0.34, P < .001 for the nostrils scale). Associations between the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale and age, gender, and race/ethnicity were not significant.

The mean score on each of the FACE-Q scales for the sample of postoperative patients was significantly lower than that for the sample of preoperative patients (P < .001, independent samples t test). The respective preoperative and postoperative mean (SD) scores were as follows:39.2 (16.6) and 74.0(23.3) for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale,50.1 (28.9) and 80.0(24.9) for the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale, 44.9 (15.2) and 70.4 (21.1) for the Satisfaction With Facial Appearance Scale, 64.3 (22.3) vs 80.4 (20.5) for the Psychological Function Scale, and 64.0 (26.1) and 77.8 (21.6) for the Social Function Scale.

The mean scores for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale according to participants’ answers to the “How attractive your nose looks?” summary question varied significantly for both scales (P < .001, analysis of variance). The range in the mean (SD) scores for the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale, respectively, were 25.0 (13.7) and 39.0 (30.3) for “very dissatisfied” and 91.0 (11.8) and 95.0 (12.8) for “very satisfied.”

Twenty-three participants (10 in the United States and 13 in England) completed the FACE-Q scales before and after surgery. Completion of the postoperative survey occurred on average 4 months (range, 1–6.5 months) after surgery. Table 4 summarizes the group-level and individual-level change results. Significant group-level improvement on all 5 FACE-Q scales was associated with moderate to large effect sizes. The effect sizes ranged from 0.6 to 2.3. For individual-level change, the number to report significant change among the 23 participants ranged from 9 for the Psychological Function Scale to 17 for both the Satisfaction With Nose Scale and the Satisfaction With Facial Appearance Scale.

Table 4.

Preoperative, Postoperative, Change, and Responsiveness Statistics for the FACE-Q Scales Among 23 Participants Who Provided Preoperative and Postoperative Data

| Variable | Satisfaction With Nose Scale | Satisfaction With Nostrils Scale | Satisfaction With Facial Appearance Scale | Psychological Function Scale | Social Function Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1, mean (SD) | 36.9 (16.6) | 45.7 (29.2) | 42.6 (15.7) | 60.7 (23.6) | 62.1 (26.6) |

| Time 2, mean (SD) | 74.6 (24.8) | 78.6 (24.8) | 73.1 (19.4) | 74.4 (20.5) | 78.0 (18.1) |

| Change (SD) | 37.7 (26.7) | 32.9 (33.6) | 30.5 (15.8) | 13.7 (18.6) | 15.9 (23.2) |

| Paired t test | |||||

| t Statistic | 6.78 | 4.71 | 9.28 | 3.54 | 3.29 |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | .002 | .003 |

| Effect size | 2.3 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Individual responsiveness, No. | |||||

| Significant improvement | 17 | 14 | 17 | 9 | 12 |

| Nonsignificant improvement | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| No change | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Nonsignificant worsening | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Significant worsening | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

Discussion

Most patients undergoing rhinoplasty seek to improve the appearance of their nose. To date, measuring change in appearance after rhinoplasty from the patient perspective has been hampered by a lack of available PRO instruments. Our team sought to address this deficit through the creation of a FACE-Q rhinoplasty module that can be used to measure the appearance and postoperative adverse effects. A strength of our study is that we were able to test 25 items and use RMT analysis to identify the best subset of items that together map out clinical hierarchies for the constructs of satisfaction with the nose and nostrils. The psychometric analyses provided evidence of reliability, validity, and ability to detect clinical change. Most important, our analysis showed that the FACE-Q scales worked the same in patients who vary by age, gender, race/ethnicity, and country.

The construct validation analyses identified differences in satisfaction with the appearance and the health-related quality of life in a sample of preoperative and postoperative patients, and our responsiveness analysis detected clinical change. More specifically, rhinoplasty surgery was associated with large effect sizes for the appearance of the nose, face, and nostrils. To put these findings into context, it is useful to consider the effect size in other cosmetic procedures. The BREAST-Q was used in a longitudinal study45 of 41 patients undergoing cosmetic breast augmentation. The effect sizes for improvement in “satisfaction with breasts,” “psychosocial well-being,” and “sexual well-being” after augmentation were 2.4, 1.7, and 1.9, respectively, and these improvements were seen in 83%, 88%, and 81%of individuals, respectively. The effect sizes for our sample of patients undergoing rhinoplasty are comparable to those for breast augmentation, higher than those for treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome (eg, 0.2 for grip strength),46 and lower than those for hip arthroplasty (eg, 3.1 for symptoms).47

Our study has several limitations. Our sample was homogeneous in that most participants were female and from the United States. As in many plastic surgery studies, the disproportionate number of women compared with men reflects the nature of cosmetic surgery patients in the general population. Given the characteristics of our sample, we are not able to answer in a definitive way how patient outcomes relate to the time since surgery. However, heterogeneity is good in PRO instrument development studies because the variability makes it possible to develop scales targeted to a wide and diverse sample. There could have been bias introduced at the individual clinic level by office staff who recruited their patients for us. We have no way of knowing for sure if dissatisfied clients were overlooked in recruitment. We believe that any recruitment bias is unlikely because the sample included participants who were “very dissatisfied” with the appearance of their nose and nostrils. Further research using the FACE-Q scales is needed. Such research could examine test-retest reliability, which we did not investigate. In addition, our sample of patients who completed the FACE-Q scales before and after their rhinoplasty was small. Future studies using these scales to examine clinical change are needed.

Conclusions

Patient satisfaction with their appearance—an important but often overlooked outcome—is able to be measured in facial aesthetics using the FACE-Q scales. Our goal in developing the FACE-Q was to provide the facial cosmetic community with a set of short, easy-to-complete, clinically meaningful, and procedure-specific scales that are scientifically sound for use in research, auditing, and clinical care. As such, the FACE-Q rhinoplasty module described in this article can be used by plastic surgeons to evaluate their individual-level or practice-level surgical outcomes to identify in what areas they are achieving patient satisfaction and, most important, where they are not. As the FACE-Q scales are adopted and used by the clinical and academic community, evidence-based outcome data from the patient perspective for surgical procedures, including rhinoplasty, will become available.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant from The Plastic Surgery Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The FACE-Q is owned by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Drs Klassen, Cano, and Pusic reported being codevelopers of the FACE-Q and, as such, reported receiving a share of any license revenues as royalties based on Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s inventor sharing policy. Dr Cano reported being cofounder of MODUS OUTCOMES, an outcomes research and consulting firm that provides services to pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology companies. No other disclosures were reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funder/sponsor had no role in any of the following: design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Previous Presentations: Preliminary results of this study were presented as posters at the 30th Annual Scientific Meeting of The British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons; September 25–26, 2014; London, England. Results of this study were presented as podium talks at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Northeastern Society of Plastic Surgeons; September 19, 2015; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and at Plastic Surgery The Meeting 2015 of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons; October 19, 2015; Boston, Massachusetts.

Author Contributions: Drs Klassen and Pusic had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Klassen, Cano, Pusic.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Klassen, East, Baker, Badia, Schwitzer, Pusic,

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Administrative, technical, or material support: All authors.

References

- 1.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. [Accessed October 9, 2015];2014 Cosmetic plastic surgery statistics. http://www.plasticsurgery.org/Documents/news-resources/statistics/2014-statistics/cosmetic-procedure-trends-2014.pdf. Published 2015.

- 2.Fatemi MJ, Rajabi F, Moosavi SJ, Soltani M. Quality of life among Iranian adults before and after rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(2):448–452. doi: 10.1007/s00266-011-9820-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pecorari G, Gramaglia C, Garzaro M, et al. Self-esteem and personality in subjects with and without body dysmorphic disorder traits undergoing cosmetic rhinoplasty: preliminary data. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(3):493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zojaji R, Keshavarzmanesh M, Arshadi HR, Mazloum Farsi Baf M, Esmaeelzadeh S. Quality of life in patients who underwent rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 2014;30(5):593–596. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alsarraf R. Outcomes research in facial plastic surgery: a review and new directions. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24(3):192–197. doi: 10.1007/s002660010031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cingi C, Eskiizmir G. Deviated nose attenuates the degree of patient satisfaction and quality of life in rhinoplasty: a prospective controlled study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2013;38(2):136–141. doi: 10.1111/coa.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chauhan N, Warner J, Adamson PA. Adolescent rhinoplasty: challenges and psychosocial and clinical outcomes. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34(4):510–516. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9489-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris DL, Carr AT. The Derriford Appearance Scale (DAS59): a new psychometric scale for the evaluation of patients with disfigurements and aesthetic problems of appearance. Br J Plast Surg. 2001;54(3):216–222. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2001.3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Picavet VA, Prokopakis EP, Gabriëls L, Jorissen M, Hellings PW. High prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder symptoms in patients seeking rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(2):509–517. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821b631f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohammadshahi M, Pourreza A, Orojlo PH, Mahmoodi M, Akbari F. Rhinoplasty as a medicalized phenomenon: a 25-center survey on quality of life before and after cosmetic rhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38(4):615–619. doi: 10.1007/s00266-014-0323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cingi C, Songu M, Bal C. Outcomes research in rhinoplasty: body image and quality of life. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25(4):263–267. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cingi C, Toros SZ, Cakli H, Gürbüz MK. Patient-reported outcomes after endonasal rhinoplasty for the long nose. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(3):1002–1006. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31829024db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simsek G, Demirtas E. Comparison of surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction after 2 different rhinoplasty techniques. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(4):1284–1286. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000000587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavinsky-Wolff M, Dolci JEL, Camargo HL, Jr, et al. Vertical dome division: a quality-of-life outcome study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(5):758–763. doi: 10.1177/0194599813480629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lindsay RW. Disease-specific quality of life outcomes in functional rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(7):1480–1488. doi: 10.1002/lary.23345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saleh AM, Younes A, Friedman O. Cosmetics and function: quality-of-life changes after rhinoplasty surgery. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):254–259. doi: 10.1002/lary.22390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Most SP. Analysis of outcomes after functional rhinoplasty using a disease-specific quality-of-life instrument. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8(5):306–309. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.8.5.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Günel C, Omurlu IK. The effect of rhinoplasty on psychosocial distress level and quality of life. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(8):1931–1935. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3282-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulut C, Wallner F, Plinkert PK, Baumann I. Development and validation of the Functional Rhinoplasty Outcome Inventory 17 (FROI-17) Rhinology. 2014;52(4):315–319. doi: 10.4193/Rhino13.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morley D, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R. [Accessed October 12, 2015];A structured review of patient-reported outcome measures used in cosmetic surgical procedures: report to Department of Health. 2013 http://phi.uhce.ox.ac.uk/pdf/Cosmetic%20Surgery%20PROMs%20Review2013.pdf.

- 21.FACE-Q. [Accessed October 9, 2015];Introducing FACE-Q. https://webcore.mskcc.org/faceq/

- 22.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Scott A, Snell L, Pusic AL. Measuring patient-reported outcomes in facial aesthetic patients: development of the FACE-Q. Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26(4):303–309. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1262313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pusic A, Klassen AF, Scott AM, et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the FACE-Q satisfaction with appearance scale: a new patient-reported outcome instrument for facial aesthetics patients. Clin Plast Surg. 2013;40:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Schwitzer JA, Scott AM, Pusic AL. FACE-Q scales for health-related quality of life, early life impact, satisfaction with outcomes, and decision to have treatment: development and validation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):375–386. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. [Accessed June 10, 2015];Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. http://www.ispor.org/workpaper/FDA%20PRO%20Guidance.pdf. Published December 2009.

- 26.Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, et al. Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(3):193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity: establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report, part 1: eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14(8):967–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity: establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report, part 2: assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011;14(8):978–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kosowski TR, McCarthy C, Reavey PL, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures after facial cosmetic surgery and/or nonsurgical facial rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123(6):1819–1827. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a3f361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khadka J, Gothwal VK, McAlinden C, Lamoureux EL, Pesudovs K. The importance of rating scales in measuring patient-reported outcomes. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrich D. Controversy and the Rasch model: a characteristic of incompatible paradigms? Med Care. 2004;42(1 suppl):I7–I16. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000103528.48582.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright BD, Masters G. Rating Scale Analysis: Rasch Measurement. Chicago, IL: MESA; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrich D, Sheridan B. RUMM2030. Perth, Australia: RUMM Laboratory; 1997–2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hobart J, Cano S. Improving the evaluation of therapeutic intervention in MS: the role of new psychometric methods. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1–200. doi: 10.3310/hta13120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrich D. Rasch Models for Measurement. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rasch G. Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for Education Research; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient α and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989;27(3 suppl):S178–S189. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katz JN, Larson MG, Phillips CB, Fossel AH, Liang MH. Comparative measurement sensitivity of short and longer health status instruments. Med Care. 1992;30(10):917–925. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hobart JC, Cano SJ, Thompson AJ. Effect sizes can be misleading: is it time to change the way we measure change? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(9):1044–1048. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.201392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32(3):221–233. doi: 10.1037/h0057532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCarthy CM, Cano SJ, Klassen AF, et al. The magnitude of effect of cosmetic breast augmentation on patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(1):218–223. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318254b3bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cano SJ, O’Connor RJ, Thompson AJ, Hobart JC. Exploring disability rating scale responsiveness II: do more response options help? Neurology. 2006;67(11):2056–2059. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247664.97643.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liang MH, Fossel AH, Larson MG. Comparisons of five health status instruments for orthopedic evaluation. Med Care. 1990;28(7):632–642. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]