Abstract

We demonstrated previously that TRPV1-dependent coupling of coronary blood flow (CBF) to metabolism is disrupted in diabetes. A critical amount of H2O2 contributes to CBF regulation; however, excessive H2O2 impairs responses. We sought to determine the extent to which differential regulation of TRPV1 by H2O2 modulates CBF and vascular reactivity in diabetes. We used contrast echocardiography to study TRPV1 knockout (V1KO), db/db diabetic, and wild type C57BKS/J (WT) mice. H2O2 dose-dependently increased CBF in WT mice, a response blocked by the TRPV1 antagonist SB366791. H2O2-induced vasodilation was significantly inhibited in db/db and V1KO mice. H2O2 caused robust SB366791-sensitive dilation in WT coronary microvessels; however, this response was attenuated in vessels from db/db and V1KO mice, suggesting H2O2-induced vasodilation occurs, in part, via TRPV1. Acute H2O2 exposure potentiated capsaicin-induced CBF responses and capsaicin-mediated vasodilation in WT mice, whereas prolonged luminal H2O2 exposure blunted capsaicin-induced vasodilation. Electrophysiology studies re-confirms acute H2O2 exposure activated TRPV1 in HEK293A and bovine aortic endothelial cells while establishing that H2O2 potentiate capsaicin-activated TRPV1 currents, whereas prolonged H2O2 exposure attenuated TRPV1 currents. Verification of H2O2-mediated activation of intrinsic TRPV1 specific currents were found in isolated mouse coronary endothelial cells from WT mice and decreased in endothelial cells from V1KO mice. These data suggest prolonged H2O2 exposure impairs TRPV1-dependent coronary vascular signaling. This may contribute to microvascular dysfunction and tissue perfusion deficits characteristic of diabetes.

Keywords: TRPV1, Reactive oxygen species, Capsaicin, Hydrogen peroxide, Coronary blood flow

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), classically defined as partially reduced metabolites of oxygen possessing strong oxidizing capabilities, cause damage to protein, DNA, and other cellular constituents. While often deleterious at high concentrations, low concentrations can serve as complex signaling components. At “physiological concentrations”, ROS function as signaling molecules that regulate cell growth, differentiation, senescence, and apoptosis [15] Dysfunctional vascular signaling as a result of enhanced ROS production is characteristic of diabetes and contributes toward the progression of associated cardiovascular pathologies. Diabetes chronically increases ROS, including hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), by numerous mechanisms including increases in pro-inflammatory enzymes and mitochondrial disturbances [46, 56]. This shifts the redox balance and induces oxidative stress. Oxidative stress has been proposed to contribute to the pathogenesis of systemic, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases [16, 19] including the development and progression of diabetic vascular complications and endothelial dysfunction [20, 26, 29].

The transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channel, a polymodal cation channel selectively stimulated by capsaicin [40, 53] is important in the pathogenesis of various diseases states including obesity and diabetes [34, 58, 65]. In particular, we have demonstrated previously that TRPV1-dependent coupling of coronary blood flow (CBF) to metabolism is disrupted in diabetic mice [21]. Chemical reactions between transduction channels and reactive chemicals have recently been proposed as effective means to alter channel sensitivities to various stimuli [50, 52, 63]. Despite the importance of oxidative stress in diabetes, knowledge of its role in modulating TRPV1 activity is not well understood. Redox modulation of ion channels, TRPV1 specifically, to oxidative stress and/or oxidative chemicals may be a key biochemical mechanism leading to altered channel functional expression of TRPV1 in response to oxidative stress environments. A critical amount of ROS and redox state within a certain level is necessary for coronary flow regulation; however, oxidative stress impairs CBF regulation in diabetes via dysfunctional TRPV1 activation.

Recently, Murthy and co-workers [38] demonstrated diabetic patients with impaired coronary flow reserve (i.e. microvascular dysfunction) and no evidence of coronary artery disease (CAD) had essentially the same annualized cardiac mortality as diabetic patients with known CAD. Understanding mechanisms associated with microvascular dysfunction could help to treat/delay the onset of more severe cardiovascular complications (cardiomyopathy) in diabetic patients. Considering tissue damage and inflammation occurs during diabetes to enhance ROS production, decreased TRPV1 functional activation following oxidative stress is likely to occur and may describe the uncoupling of CBF to metabolism observed in diabetic animals. Since coronary arteriolar dilation to H2O2 is a redox sensitive process, a fundamental goal toward understanding the mechanisms coupling CBF to metabolism is to identify molecules that transduce changes in metabolic demand to modulation of CBF. Thus, we hypothesize that H2O2 transduction of metabolic signals in coronary dilation is TRPV1 dependent and that H2O2 differentially regulates TRPV1 to alter vascular responses in coronary tissue. Specifically, H2O2 will stimulate TRPV1 to elicit dilation at lower doses or times of exposure, compared to damaging vascular dilator machinery to inhibit dilation at larger doses or durations of exposure. We believe the difference in whether ROS exerts a beneficial or detrimental effect relates to the amount and duration of ROS exposure. Therefore different levels of oxidative stress may cause TRPV1 to respond in a graded fashion, and modify TRPV1 responses including CBF regulation leading to microvascular dysfunction in diabetes. In the present study, we used an integrated approach to address the ability of H2O2 to differentially regulate TRPV1 activity to alter vascular responses. We demonstrate prolonged H2O2 exposure disrupts TRPV1-dependent coronary vascular signaling, which may result in tissue perfusion impairments characteristic of diabetes.

Methods and materials

Mice

All procedures were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Northeast Ohio Medical University (NEOMED) and in accordance with National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication 2011). Mice breeding pairs were originally purchased from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME) after which mice were bred in the NEOMED animal facility. Experiments were performed in 10-12 week-old male TRPV1 Knockout (V1KO—C57BK/6 background), db/db or aged-matched, C57BKS/J (WT) mice as controls. Mice were housed in a temperature-controlled room with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and maintained with access to food and water ad libitum.

Jugular and femoral artery catheterization

Mice received a surgical plane of inhaled anesthesia with 1.5–2.5 % sevoflurane gas with supplemental oxygen, using a veterinary anesthesia and monitoring device. Animals were placed on controlled heating table, maintained at 37 °C with core temperature measured via a rectal probe. Mice were secured in the supine position and placed under a dissecting microscope. The right jugular vein was cannulated for intravenous drug infusions and contrast infusion. See methods and materials section from Guarini et al., [21] for complete description.

Contrast echocardiography CBF measurements

For myocardial contrast echocardiography (MCE), animals were prepared as above. Mice were infused with capsaicin (1–100 μg/kg) or H2O2 (0.2, 0.4, 2 and 4 μmol/kg/min) alone and non-targeted contrast. Importantly, only during the in vivo potentiation experiments were Capsaicin and H2O2 infused simultaneously. For complete description of methods, see methods and materials section from Guarini et al. [21].

Experimental protocol

Following each surgery, mice were given a bolus injection of the ganglionic blocker hexamethonium (HEX, 5 mg/kg, Sigma) to eliminate reflex adjustments and focus on the primary vascular actions of capsaicin. Initial studies were performed to determine the effects of continuous infusion of H2O2 and/or capsaicin administered in an escalating fashion at the rate of 20 μl/min for 4 min Hemodynamic response curves were performed in WT, db/db and V1KO mice, before and after inhibition of TRPV1 channels (SB366791—100 μg/kg iv, Sigma). 10 min elapsed following each inhibitor before H2O2 and/or capsaicin infusion began to allow for MAP to stabilize. Pressures and/or heart rate were continuously recorded throughout the experiment. A subset of db/db mice were injected (via tail vein administration) with PEG-Catalase (three times per week 7000 Units/injection) for 1 week and subjected to capsaicin to examine blood flow responses.

Isolated coronary microvessel reactivity studies

Mice were anesthetized and hearts were excised and placed in ice-cold physiological saline solution. Coronary arterioles were dissected free from ventricular wall tissue in buffer containing (mM) 145 NaCl, 5.0 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.17 MgSO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 10 glucose; pH 7.4. Isolated vessels were then cannulated with glass pipettes and secured with silk suture in a temperature-controlled chamber (Danish Myotech, DMT, Atlanta, Georgia) mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope outfitted with a video camera and edge detection analyzer. Arterioles were pressurized to 60 mmHg and warmed to 37 °C. Vessel viability was determined using 60 mM KCl. Vessels were pre-contracted with the thromboxane mimetic, U46619 (1 μM) and subsequent H2O2, sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and capsaicin-mediated relaxation was assessed in the presence and absence of various reducing agents as well as pharmacological inhibitors of TRPV1 and voltage-gated potassium channels. Similarly, the effects of DTT on KCl-mediated contraction were examined. Drugs were administered in 4 min increments with steady state diameter measurements taken over the course of the final 30 s of concentration exposure. For statistical purposes, each vessel represents one experiment performed thus n = number of vessels.

Endothelium disruption

The endothelium was disabled in a subset of coronary arteriole experiments by passing ∼ 1 ml of air through the lumen. Disruption of the endothelium was assessed by exposing U46619-constricted arterioles to Acetylcholine (ACh, 1 μM). Only arterioles where ACh-mediated vasodilation was absent (<10 %) were used.

Isolation of mouse coronary endothelial cells (MCECs)

Endothelial cells were isolated using the aortic explant method. Briefly, aortic rings and coronary microvessels were placed in Matrigel for 7 days. The vascular tissue was carefully removed, and endothelial cells were isolated, washed, and plated on gelatin (0.1 %)-coated dishes. Mouse aortic endothelial cells (MAEC) and coronary endothelial (MCECs) were cultured on fibronectin-coated tissue culture dishes and grown in a defined medium composed of low-glucose DMEM, 10 % FBS, 10 % Nu Serum IV, basic fibroblast growth factor (6 ng/ml), heparin salt (0.1 mg/ml), 1 % insulin-transferrin-selenium, and antibiotic/mycotic mix. Cells were cultured in a 37 °C, 5 % CO2 incubator, split at ∼90–95 % confluence, and used between passages 11 and 22. HEK-293 cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM, 10 % FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5 % CO2 environment. Mouse Coronary Endothelial Cells (MCEC) from C57BL6 mice were acquired from Cell Biologics (Chicago, IL) and grown in provided EC media containing VEGF, ECGS, Heparin, EGF, Hydrocortisone, l-Glutamine, Antibiotic–Antimycotic solution and FBS.

Cell culture and transient transfection

Human Embryonic Kidney-293A (HEK293) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Media (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 % Fetal Bovine Serum, 2 mM l-Glutamine, 100 U/ml Penicillin and 100 μg/ml Streptomycin. Bovine aortic endothelial (BAECs) cells were maintained (from passages 3 to 9) in Bovine endothelia cell growth media from Cell Applications (San Diego, CA). Both BAEC and HEK293A cells were plated in a 12-well plate for 24 h. after which, cells were transfected with Mirus TransIT®-2020 according to the manufactures protocol. pCDNA3-Rat TRPV1 (Gift from Dr. David Julius) was co-transfected with EGFP-N1 (Clontech) (4:1 ratio). Cells were trypsinized and used within 36–48 h following transfection.

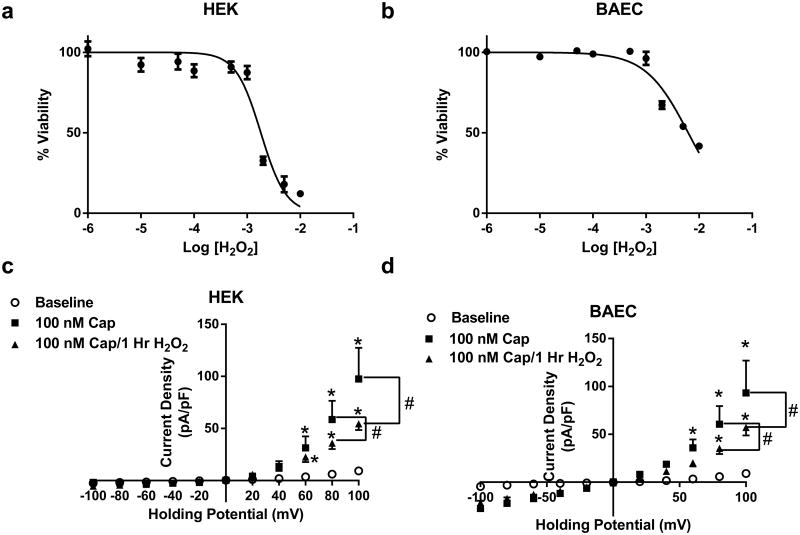

Cell survival assay

To examine the effects of prolonged H2O2 exposure on cell survival, a Presto blue assay (measure of cell survival) was performed on HEK and BAECs following prolonged H2O2 treatment (1 h) at concentrations ranging from 10 μM to 10 mM. Briefly, HEK and BAEC cells were seeded into a 96-well plate and allowed to grow to confluence. Cells were treated with H2O2 in complete media (1 uM to 10 mM) for 1 h. Following the 1 h treatment, H2O2 media was removed and cells were washed with PBS. Presto blue reagent (Invitrogen) was added to complete media and 100uL of Presto blue and complete DMEM media were added to each well. Following a 2 h incubation, plates were read for Fluorescence (535 nm excitation/615 nm emission). Each treatment was done in triplicate and data represents 3 separate experiments.

Patch-clamp electrophysiology

The whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed at room temperature in transfected HEK and BAEC cells. Data were acquired and analyzed using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pCLAMP10 software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Currents were filtered with a low pass Bessel filter at 1 kHz and sampled at 5 kHz. Borosilicate pipettes (Sutter, Novato, CA, USA) were polished to resistances of 0.5–3 MΩ. I–V relations were obtained as previously described [6]. After whole-cell access was established, series resistance and membrane capacitance were compensated as completely as possible. Current–voltage relationships were assessed by 400-ms step pulses from −100 to +100 mV in 20-mV increments from −40 mV holding potential. Steady state currents (average of 350–400 ms intervals) were used to generate I/V plots. Similarly, MCECs were held and recorded at −60 mV holding potential in response to H2O2. In whole-cell patch the extracellular bath solution contained (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Glucose, 10 HEPES 5 Tris-base, and pH 7.4 with NaOH. Intracellular solutions contained 140 KCl 1 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 5 MgATP, 1 Na-GTP, 10 HEPES, 5 Tris-base, and pH 7.1 with KOH.

Drugs

All drugs were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise stated. Capsaicin and Penitrem A were dissolved in stock solutions of ethanol. SB366791 was dissolved in DMSO. Hexamethonium (5 mg/ml) stock solution was made up in saline. Vehicles had no effects on vascular or electrophysiology responses.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made with paired t tests or two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA; with Bonferroni multiple comparison) as appropriate. For statistical analyses, GraphPad Prism 6.0 software for Windows 7 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif) was utilized. In all tests, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

H2O2 mediated vascular signaling in vivo and in vitro is, in part, TRPV1 dependent

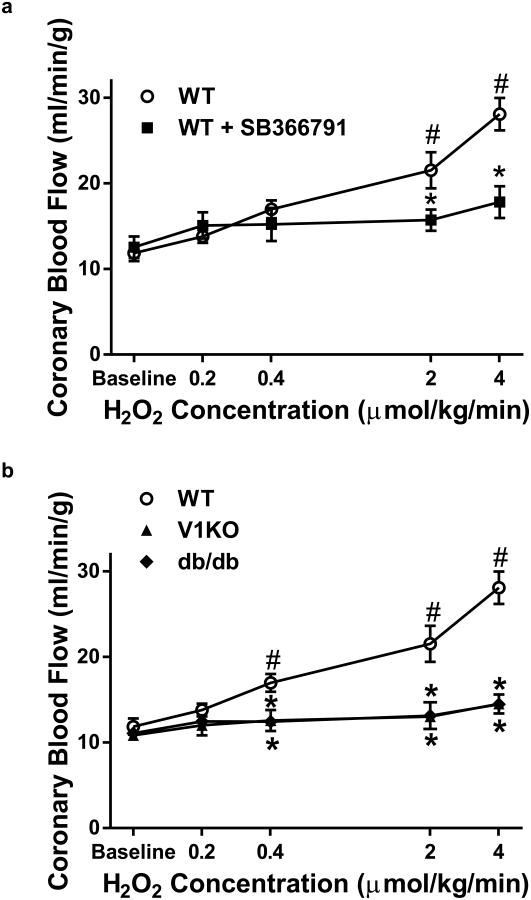

The ability of H2O2 to regulate CBF was examined in vivo. Heart rate and mean arterial blood pressure were monitored throughout the experiments and did not change significantly (See Supplemental Table 1), suggesting that with intravenous infusion, the cardiovascular effects of H2O2 were limited to the coronary circulation. Importantly, since H2O2 did not influence heart rate (HR) or perfusion pressure, increases in blood flow represent reductions in coronary vascular resistance, i.e., vascular relaxation. H2O2 infusion (0.2–4 μmol/kg/min) increased CBF in a dose-dependent manner in WT mice (Fig. 1a), while SB366791 (100 μg/kg), a TRPV1 channel antagonist, significantly attenuated H2O2-induced increases in CBF (Fig. 1a), indicating H2O2-mediated increases in CBF is, in part, mediated through TRPV1 channels. Compared to WT mice, H2O2-mediated increases in CBF were significantly reduced in V1KO and db/db mice (Fig. 1b). This suggests two things: (1) H2O2-induced increases in CBF are mediated in part by TRPV1 channels (based on the lack of response in V1KO mice) and (2) that the coupling of this H2O2-TRPV1 channel mechanism to increases in CBF is disrupted by metabolic diseases (based on blunted responses in the db/db mice).

Fig. 1.

Acute H2O2 infusion increases CBF via TRPV1 activation. a Contrast echocardiography flow measurements of CBF in WT (n = 8) mice during baseline and in response to H2O2 in the presence of SB366791 (100 μg/kg; n = 6). b V1KO (n = 6) and db/db (n = 6) mice displayed attenuated responses in flow at any dose of H2O2 compared to WT. *P < 0.05 vs. WT analyzed by two-way ANOVA. #P < 0.05 vs. baseline analyzed by two-way ANOVA

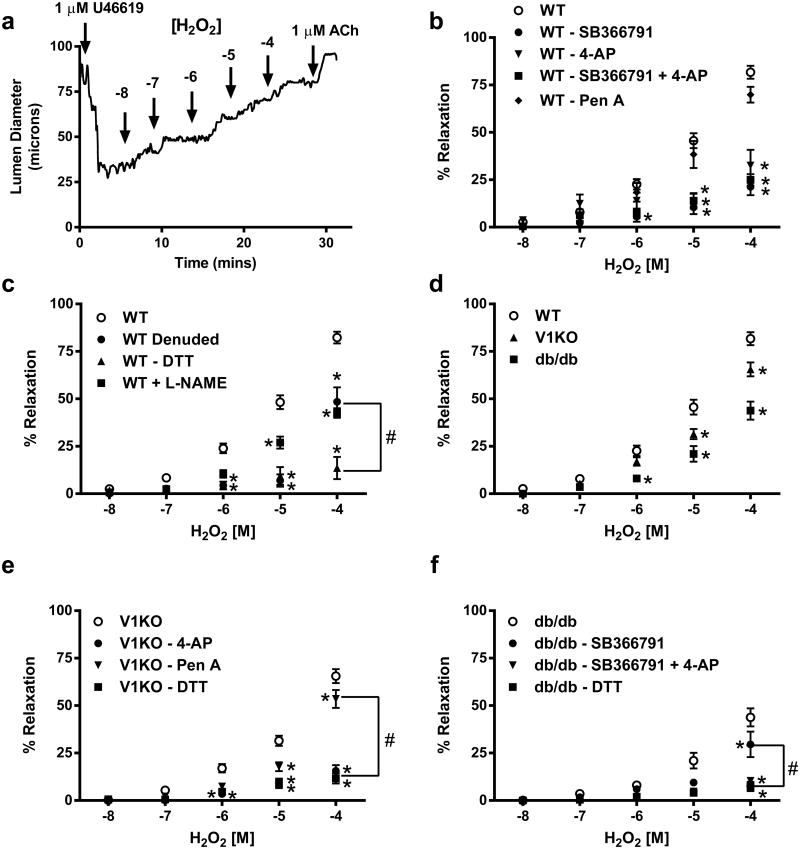

H2O2-mediated vascular signaling in vitro was investigated in coronary microvessels dissected from murine hearts. Isolated coronary microvessels were cannulated, pressurized and subsequently pre-contracted with the thromboxane mimetic U46619 (1 μM). Following contraction, vessels were exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2 (10 nM–100 μM). Isolated coronary microvessels from WT mice dilated significantly when exposed to increasing concentrations of H2O2 (Fig. 2b). This relaxation was markedly attenuated by pre-incubation with the TRPV1 inhibitor, SB366791 (10 μM). To further examine the contribution of other H2O2-sensitive channels in mediating coronary vascular relaxation, vessels were exposed to specific antagonists for the voltage-gated potassium (KV) channel (4-aminopyridine, 4-AP, 3 mM) and the large conductance, calcium-sensitive potassium (BK) channel (Penitrem A, Pen A, 10 μM). Incubation with 4-AP blunted the H2O2 mediated relaxation (Fig. 2b) and was completely abolished with the combination of 4-AP and SB366791 (Fig. 2b) indicating roles for both KV and TRPV1 channels in H2O2-mediated vasorelaxation. Pen A slightly attenuated H2O2-mediated relaxation in WT and V1KO mice yet had a minimal effect on the dilatory response to H2O2 in diabetic mice indicating little, if any role of BK channels in this response.

Fig. 2.

Acute H2O2 signaling is in part mediated through TRPV1 activation. a Representative trace of diameter changes in coronary arteriole from control animal. b Summary data of H2O2 mediated relaxation from WT mice under baseline conditions (n = 37) and following inhibition of TRPV1 with SB366791 (10 μM; n = 6) and two potassium channel inhibitors; Pen A (BK channel, 10 μM; n = 6) and 4-AP (KV channel, 10 μM; n = 6). c Summary data of H2O2 mediated relaxation from WT mice under baseline conditions (n = 37) and following endothelial denuding and in the presence of the reducing agent DTT and L-NAME (n = 6 each). d Data comparing H2O2-mediated relaxation in isolated vessels from WT (n = 37), V1KO (n = 24) and db/db (n = 12) mice under baseline conditions. e Data of H2O2-mediated relaxation from V1KO mice under baseline conditions (n = 24) and in the presence and absence of the antagonists 4-AP (n = 6), Pen A (n = 6) and DTT (n = 6), respectively. f Summary data of H2O2-mediated relaxation from db/db mice under baseline conditions (n = 12) and with SB366791 (10 μM), the potassium channel inhibitor 4-AP, the combination of both or the reducing agent DTT (n = 6 for each group). *P < 0.05 vs. control analyzed by two-way ANOVA. #P < 0.05 vs. groups at 100 μM H2O2 analyzed by two-way ANOVA

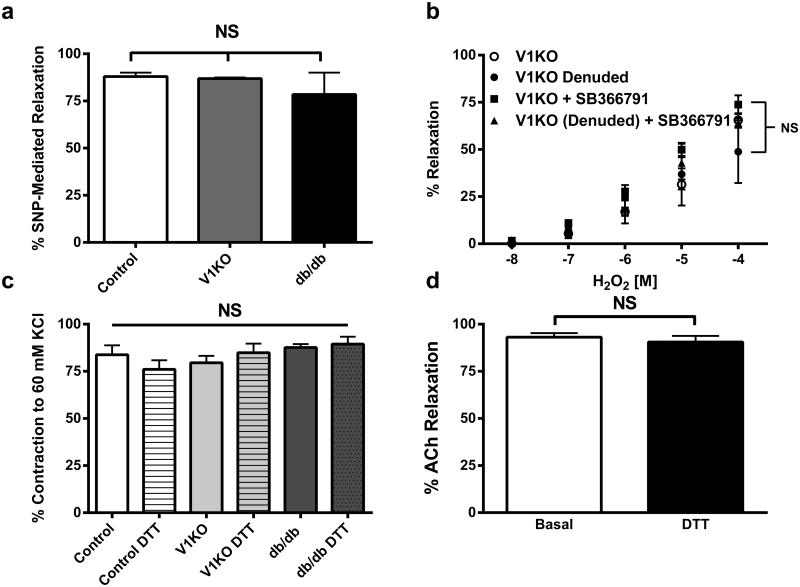

Having confirmed coronary dilation to TRPV1 agonist stimulation in previous studies is endothelium-dependent [21], we sought to determine the contribution of endothelial TRPV1 channels to the observed H2O2-induced coronary dilation. This was achieved by removal of the coronary endothelium prior to the H2O2 dose–response treatment. Importantly, endothelial denuding and L-NAME pretreatment significantly decreased the H2O2-mediated relaxation in WT mice (Fig. 2c). No effect of endothelial denuding was observed on this response in vessels isolated from V1KO mice (Fig. 3b). Similarly, SB3667791 had no effect on H2O2 relaxation in endothelial- intact or -denuded vessels in V1KO mice (Fig. 3b). Since reactive thiol groups (particularly cysteine residues) of proteins are major H2O2 signaling targets, the thiol-specific reducing agent Dithiothreitol (DTT) was used to reverse H2O2-induced relaxation. Importantly, addition of DTT did not alter vessel viability as 60 mM K+-induced contractions were identical before and after addition of DTT (Fig. 3c). Exposure of coronary microvessels to 10 μM DTT abolished the H2O2-mediated vasodilation in all vessels suggesting H2O2 may mediate these effects via its action on thiol groups of proteins (Fig. 2c, e, f). DTT had no effect on ACh-induced relaxation (Fig. 3d), suggesting the effect of DTT is specific for H2O2-induced relaxation.

Fig. 3.

Effects of SNP and DTT on vascular reactivity. a SNP-mediated relaxations were not different between groups (n = 6). b Summary data of SB366791, endothelial denuding and the combination of both in vessels isolated from V1KO mice (n = 6). c Addition of DTT did not alter vessel viability as 60 mM K+-induced contractions were identical before and after addition of DTT (n = 6). d DTT had no effect on ACh-induced relaxation (n = 6)

Next we found the H2O2-dependent dilation in V1KO mice is attenuated when compared to WT, further indicating a role for TRPV1 in mediating this observed response (Fig. 2d). Incubation of vessels from V1KO animals with 4-AP, DTT and endothelial denuding significantly attenuated the residual H2O2 mediated relaxation (Fig. 2e). Furthermore, addition of SB366791 had no effect on relaxation. Similarly, H2O2 dose-dependently relaxed vessels contracted to U46619 (1 μM) from db/db mice, yet H2O2-mediated relaxation was blunted compared to WT (Fig. 2f). SB366791 had no effect on H2O2-mediated relaxation, whereas 4-AP and DTT blocked the remaining residual H2O2 relaxation in db/db mice (Fig. 2f).

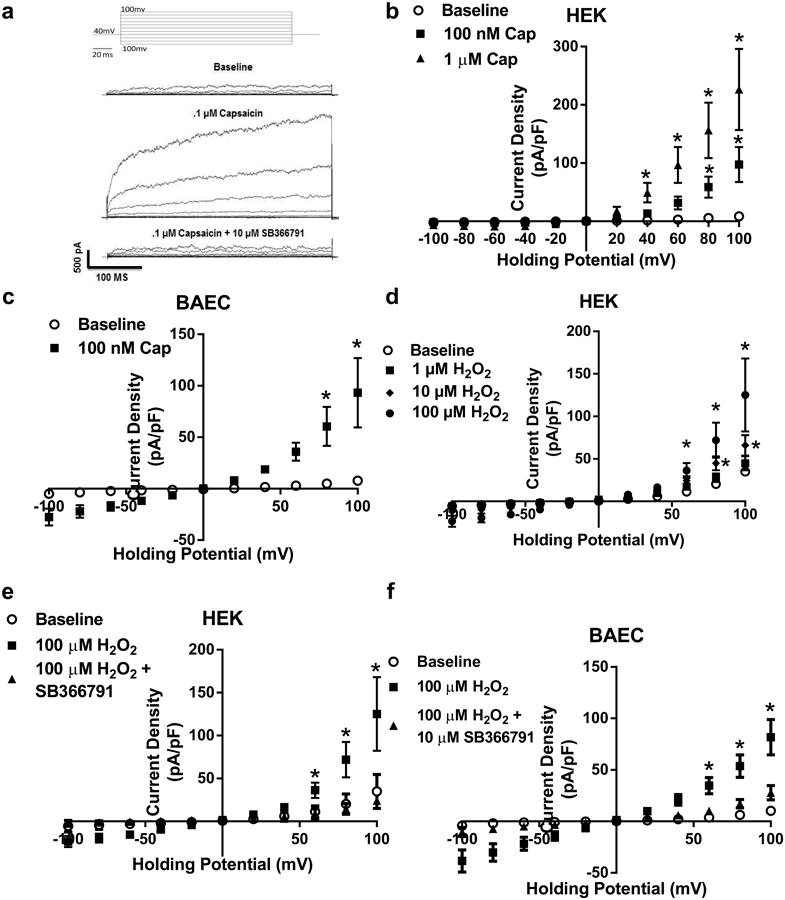

Using electrophysiology, pCDNA3-TRPV1 transfected HEK-293 and bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) demonstrated dose-dependent increases in current by capsaicin (0.1–1 μM) (Fig. 4a–c). Next TRPV1-mediated currents were recorded in response to increasing concentrations of H2O2 (1–100 μM) in the presence and absence of SB366791 (Fig. 4d). Similar to capsaicin, H2O2 dose dependently increased TRPV1 current (confirming previous findings [9]), which was blocked by SB366791 (Fig. 4d; Supplemental Fig. 1c). Verification of H2O2-mediated activation of intrinsicTRPV1 was examined in MCECs from WT and V1KO mice. Quantification of H2O2-mediated currents were significantly decreased in MCECs from V1KO mice (Fig. 4e–g).

Fig. 4.

Acute H2O2 activates TRPV1. a Representative whole-cell traces to capsaicin in the presence and absence of the TRPV1 antagonist SB366791 during a 400 ms voltage step protocol from −100 to 100 mV. The voltage protocol is placed at the top. b Summary voltage-current (I–V) curve of capsaicin-mediated activation of TRPV1 in our cell line of HEK293A cells co-transfected with TRPV1 and eGFP (n = 6 cells). c Summary voltage-current (I– V) curve of capsaicin-mediated activation of TRPV1 in BAEC cells transfect with TRPV1 and eGFP (n = 5 cells). d Patch clamp data of H2O2-mediated activation of TRPV1 specific currents in BAECs in the presence and absence of TRPV1 inhibition (100 μM H2O2, n = 6; 10 μM SB366791, n = 4 cells). e mouse coronary endothelial cells (MCECs) and f V1KO aortic endothelial cells. Cells were held at −60 mV and exposed to H2O2. g Summarized H2O2-mediated currents in MCECs from WT and V1KO mice. *P < 0.05 vs. WT MCEC by student t test (g); *P < 0.05 vs. baseline analyzed by two-way ANOVA (b–d)

Acute exposure leads to TRPV1 potentiation/sensitization by H2O2

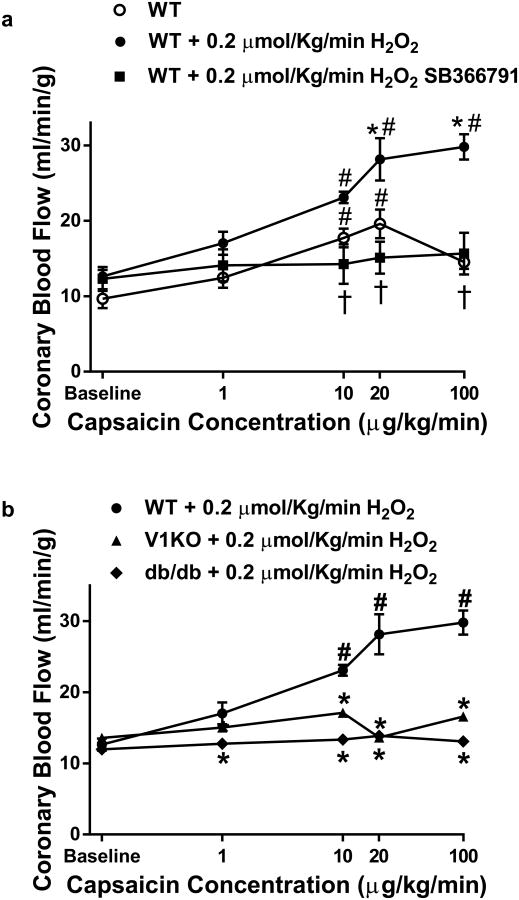

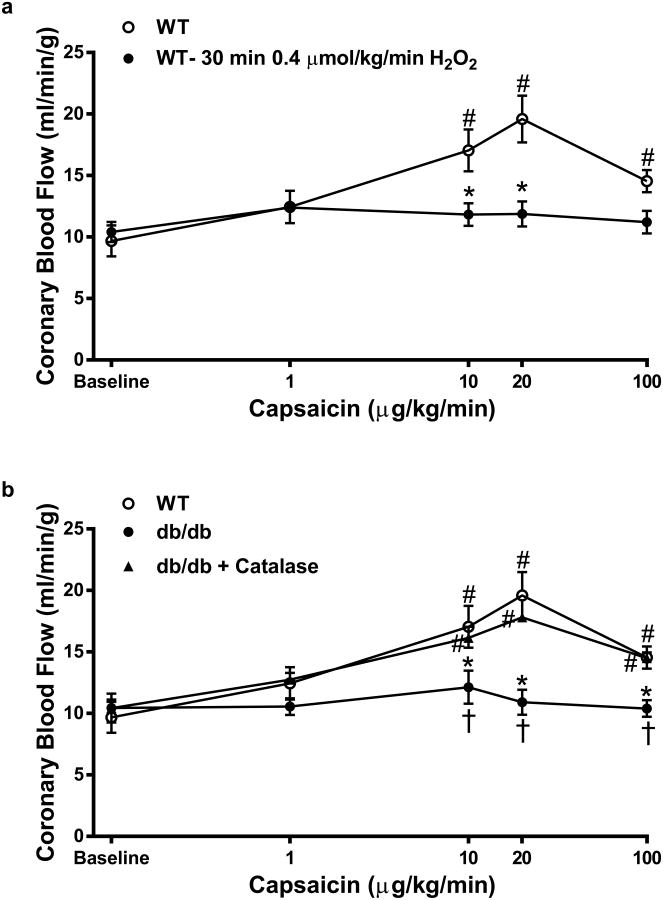

We next examined if (1) acute H2O2 exposure potentiated capsaicin-mediated responses and (2) if prolonged H2O2 exposure disrupted TRPV1 activity and signaling. Initial experiments were again performed in vivo examining changes in CBF. Capsaicin-mediated increases in CBF were determined immediately following brief (less than 5 min) exposure to a single dose of H2O2 (0.2 μmol/kg). We found capsaicin-mediated increases in CBF were potentiated following a brief exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 5a) in WT mice, whereas these potentiated responses were blunted in the presence of SB366791 (Fig. 5a) in WT mice and not observed in V1KO and db/db mice (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

H2O2 potentiates capsaicin induced increases in CBF. a Contrast echocardiography measurements of CBF demonstrating the ability of H2O2 to potentiate capsaicin-mediated increases in CBF compared to capsaicin alone and in presence of the SB366791 (100 μg/kg; n = 7) i.v. infusion over 10 min b V1KO and db/db mice (n = 6, each group) displayed little to no changes in CBF in response to H2O2 infusion. *P < 0.05 vs. WT analyzed by two-way ANOVA. #P < 0.05 vs. baseline analyzed by two-way ANOVA. $P < 0.05 vs. WT+0.2 μM/kg/min H2O2 analyzed by two-way ANOVA

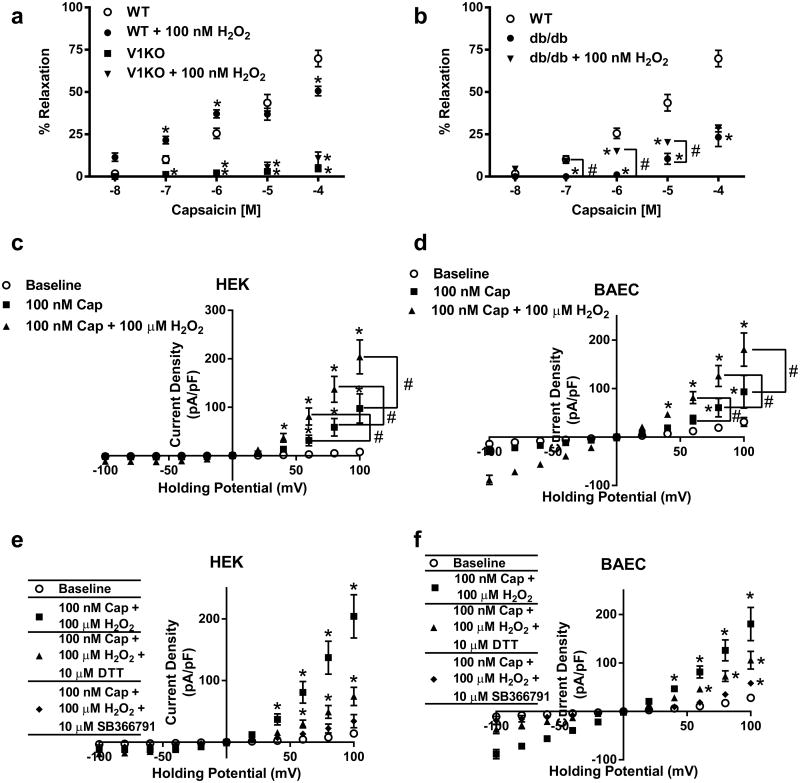

Similar to in vivo responses, H2O2 effects on capsaicin-mediated relaxations were examined following acute exposure to H2O2 in coronary microvessels. 100 nM H2O2 was chosen in order to expose TRPV1 to a concentration that would contribute to TRPV1 signal without confounding the responses with the potential effects of KV and/or BK channel activation. We found microvessels from WT mice exposed to acute administration of H2O2 (100 nM) exhibited enhanced capsaicin–dependent dilation at low capsaicin concentrations (Fig. 6a) suggesting brief exposure to H2O2 sensitized TRPV1 channels to agonist (capsaicin) stimulation indicating H2O2 indeed possesses a unique ability to sensitize, or potentiate, TRPV1 activity in the murine coronary vasculature. Responses were next examined in V1KO and db/db mice. The potentiation response observed in vessels isolated from WT mice was absent in vessels isolated from V1KO mice at all concentrations of capsaicin following acute H2O2 exposure (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, vessels isolated from db/db mice exhibited increased relaxation only at lower concentrations of capsaicin following H2O2 exposure when compared to baseline, but this response was still attenuated when compared to controls (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

H2O2 mediated potentiation of TRPV1 activity. Summary data depicting capsaicin-mediated relaxation in vessels from, a V1KO and b db/db mice compared to WT following exposure to increasing concentrations of capsaicin in the presence and absence of acute H2O2 (100 nM; n = 6 in each group). c Patch clamp data of H2O2-mediated potentiation of TRPV1 specific currents in BAEC cells (n = 6 cells). d Patch clamp data of H2O2-mediated potentiation of TRPV1 specific currents in BAEC in the presence and absence of TRPV1 inhibition and DTT (n = 6 DTT, n = 5 SB366791). *P < 0.05 vs. control analyzed by two-way ANOVA. #P < 0.05 vs. group analyzed by two-way ANOVA

The ability of H2O2 to potentiate TRPV1-dependent currents were next examined and revealed similar findings to those found in vivo and in vitro. Co-treatment with H2O2 (100 μM) significantly potentiated capsaicin-mediated TRPV1-specific currents (Fig. 6c; Supplemental Fig. 1d) in both cell types, which was absent in cells pretreated with SB366791 and/or DTT (Fig. 6d and Supplemental Fig. 1e). Cells pretreated with DTT demonstrate reduced H2O2 specific TRPV1-mediated activation.

Prolonged exposure to H2O2 leads to TRPV1 desensitization

The effects of prolonged H2O2 exposure (30 min; 0.4 μM/kg) to TRPV1-dependent signaling were next examined both in vivo and in vitro as well as at the cellular levels. Prolonged exposure markedly attenuated capsaicin-mediated increases in CBF in WT animals (Fig. 7a), similar to responses in db/db mice (Fig. 7b). SB366791 had little effect on CBF following prolonged H2O2 exposure. Furthermore, db/db mice treated with PEG-Catalase for 1 week, demonstrated significant improvement in CBF (Fig. 7b). We used X-band EPR to analyze the redox status of the myocardium during the oxidation of CM-H (a spin probe of cyclic hydroxylamine) to a stable nitroxide in myocardium tissue homogenate. Under non-energized conditions (without external substrate NADH or succinate stimulation), the redox activity of db/db myocardium was significantly oxidized, based on a higher activity of conversion of CM-H to stable nitroxide (Supplemental Fig. 3a) compared to WT. Lastly, PEG-Catalase treatment significantly reduced the redox state of the myocardium in db/db mice (Supplemental Fig. 3a) which corresponded to decreased H2O2-dependent CM-H oxidation rate (Supplemental Fig. 3b).

Fig. 7.

Prolonged H2O2 infusion blunts capsaicin-mediated increases in CBF. a Contrast echocardiography flow measurements of CBF in mice during baseline and in response to prolonged H2O2 infusion (0.4 μM/kg/min for 30 min; n = 6 in each group). b Contrast echocardiography flow measurements of CBF in mice during baseline and in response to Capsaicin infusion (n = 5–6 in each group) in WT, db/db and PEG-Catalase treated db/db mice *P < 0.05 vs. WT analyzed by two-way ANOVA. #P < 0.05 vs. baseline analyzed by two-way ANOVA. $P < 0.05 vs db/db + PEG-Catalase analyzed by two-way ANOVA

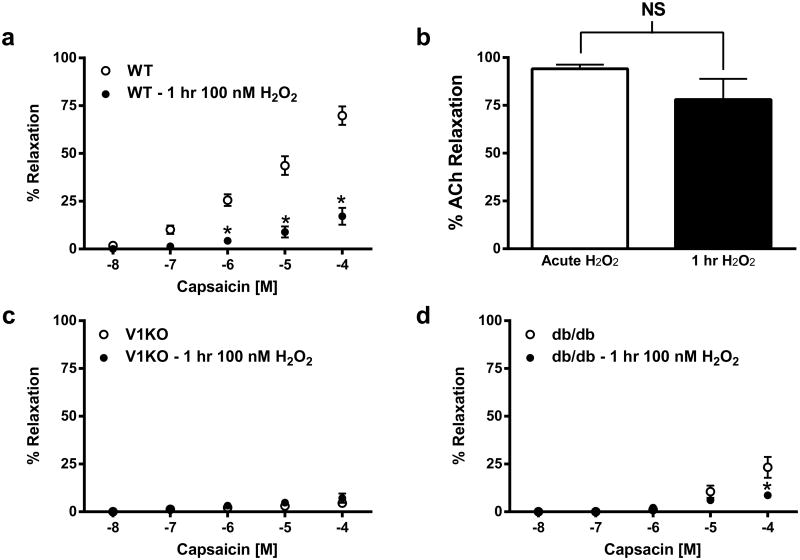

Isolated coronary microvessels from WT, V1KO, and db/db mice were next exposed to increasing concentrations of capsaicin (10 nM–100 μM), prior to and following luminal exposure to H2O2 (100 nM) for 1 h. Prolonged intraluminal exposure to H2O2 in vessels isolated from WT mice exhibited significantly blunted capsaicin-mediated relaxation (Fig. 8a), while vessels isolated from V1KO mice exhibited no response to capsaicin-mediated relaxation following long term H2O2 exposure (Fig. 8c). Similarly, vessels isolated from db/db mice exhibited minimal capsaicin-mediated relaxation under the same conditions (Fig. 8d). Acetylcholine (ACh)-dependent relaxation (1 μM) was used to confirm H2O2 (100 nM) exposure was not affecting vessel and endothelial integrity. ACh relaxation did not differ in vessels following chronic exposure to H2O2 (Fig. 8b).

Fig. 8.

Prolonged H2O2 exposure leads to TRPV1 desensitization and attenuated TRPV1 signaling. Summary data of vessel relaxation to capsaicin in vessels isolated from WT (a), V1KO (c) and db/db (d) mice following prolonged intraluminal exposure to H2O2 (100 nM; 1 h, n = 6 in each group). b Increased H2O2 exposure does not affect endothelial-dependent relaxation

The effects of prolonged H2O2 exposure on TRPV1-dependent currents were also studied in TRPV1 expressing HEK and BAEC cells. Similar to our in vivo and in vitro results, capsaicin-mediated TRPV1 currents were markedly attenuated compared to baseline non-treated conditions following 1 h treatment with 100 μM H2O2 (Fig. 9c, d), which was not due to decreased TRPV1 expression (Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 9.

HEK (a) and BAEC (b) cells were analyzed for cell survivability following 1 h treatment with H2O2. HEK cells demonstrate an EC50 of 1.81 mM (R2 = 0.79). BAEC cells demonstrated an EC50 of 6.24 mM (R2 = 0.85) Experiments were performed in replicates of four in three separate experiments. c Patch clamp data of prolonged (1 h) 100 μM H2O2-mediated desensitization of TRPV1 currents in HEK293 cells (n = 6 cells). d Patch clamp data of prolonged (1 h) 100 μM H2O2-mediated desensitization of TRPV1 currents in BAEC cells (n = 6 cells). *P < 0.05 vs. control analyzed by two-way ANOVA. #P < 0.05 vs. 100 nM Cap analyzed by two-way ANOVA

Discussion

There is an ideal redox window in which normal production of H2O2 regulates CBF [49], but excessive H2O2 production impairs coronary vascular responses. Previously, we demonstrated diabetes disrupts the TRPV1-dependent coupling of CBF to myocardial metabolism [21], but the underlying mechanism(s) remain unclear. The present study was designed to determine the extent to which differential regulation of TRPV1 by H2O2 modulates CBF and vascular reactivity in diabetes. Data from the current study confirm the ability of H2O2 to directly activate as originally reported by Chuang and Lin (2009), sensitize and/or demonstrate its ability to desensitize coronary TRPV1 function. Our study produced the corresponding 5 major findings: (1) Reconfirmation of H2O2 activation of TRPV1 channels [9, 52] and potentiated capsaicin-activated TRPV1 currents. (2) Prolonged and excessive exposure to H2O2 attenuated capsaicin-induced TRPV1 currents in HEK293A and endothelial cells. (3) H2O2 increased CBF in WT mice, a response blocked by the TRPV1 antagonist SB366791. Importantly, however, H2O2-induced vasodilation was significantly inhibited in both db/db and V1KO mice. (4) In WT mice, acute H2O2 exposure potentiated capsaicin-induced CBF responses and capsaicin-mediated dilation of coronary microvessels. In db/db and V1KO mice, however, H2O2 had very little potentiating effect on capsaicin-induced CBF responses or capsaicin-mediated coronary vasodilation. (5) In WT mice, prolonged exposure to elevated H2O2 impaired capsaicin-induced CBF responses and capsaicin-induced vasodilation. In fact, after excessive H2O2 exposure, the CBF and microvessel responses of WT mice resembled the impaired responses of V1KO and db/db mice. Importantly, PEG-Catalase treatment improved CBF responses in db/db mice, concomitant with reduced myocardial redox state corresponding to decreased H2O2-dependent CM-H oxidation rate. Together, these findings lead us to conclude that acute H2O2 exposure activates or potentiates TRPV1-mediated responses, whereas prolonged exposure to H2O2 impairs TRPV1-dependent coronary vascular signaling.

This study provides compelling evidence that H2O2 differentially regulates TRPV1 channels to alter TRPV1-dependent coronary vascular reactivity in mice. The ability of H2O2 to directly activate and contribute to TRPV1 mediated signaling was initially demonstrated using electrophysiology. These results translated to the vascular and whole animal levels as H2O2 induced a near complete dilation in isolated coronary microvessels from WT mice, which was reduced significantly in the presence of the TRPV1 antagonist SB366791 and in V1KO mice. Although, these findings highlight the fact that H2O2-mediates its responses through TRPV1, these effects are not completely abolished suggesting the participation of other channels. In fact, pharmacological TRPV1 inhibition may overestimate the role of TRPV1 in H2O2-mediated relaxation; however, knock out data demonstrates a significant contribution of TRPV1 to H2O2 relaxation. The remaining TRPV1-independent H2O2-mediated relaxation may be due to the compensatory mechanisms in V1KO mice such as KV channels (as indicated by 4-AP-mediated suppression of H2O2-mediated relaxation in V1KO mice). Indeed, we found that blocking KV channels with 4-AP together with SB366791 completely abolished H2O2-induced vasodilation, consistent with previous studies on KV channels, [2, 42, 47, 48]—reinforcing a role for TRPV1. BKCa channels have been shown to contribute to arterial tone[33], however, unlike BKCa-dependent H2O2-induced dilation in previous studies [3, 64], the BKCa channel did not contribute significantly to the dilatory effect in our study, suggesting that the H2O2-dependent sensitivity of K+ channels differs among vascular beds and perhaps species. Furthermore, other ion channels cannot be discounted as additional channels, that are described in endothelial and smooth muscle cells (e.g. TRPV4, voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, ORAIs, TRPM6/M7, TRPC6) [5, 44], could also mediate this effect. Endothelial Derived Hyperpolarizing Factors (EDHFs) contribute to regulation of vascular tone [37, 62]. H2O2 has been linked to EDHFs [4]: as endothelial H2O2 production, which can reach 500 μM H2O2 [11, 18], leads to vessel relaxation [31, 36]. The contribution of EDHFs to vascular tone is still debatable, but EDHF is thought to be prevalent in resistance vessels; while nitric oxide regulates larger vessels [10]. While H2O2 is often thought of as an endothelial-independent vasodilator, the blunted H2O2 relaxation in denuded vessels from WT animals, reinforce a role for endothelial TRPV1 (blunted response) and vascular K channels (residual response) [47, 48]. A role for vascular TRPV1 expression and contribution to the responses can not be discounted as recent studies have demonstrated a role for vascular TRPV1 in various beds. In particular, a recent study by Hiett and co-workers [24] demonstrated a role for vascular TRPV1 in coronary vasospasm in canines. Similarly, a role for neuronal TRPV1 activation and resultant CGRP-mediated dilation cannot be discounted. However, hexamethonium administration would likely diminish a role for CGRP-induced vasodilation as pre-synaptic transmission would be blocked, however the possibility of post-synaptic TRPV1 activation resulting in CGRP release cannot be discounted.

ROS are important modulators of TRPV1 activity to agonist stimulation, whereas oxidative stress diminishes cardiovascular function (e.g., endothelial dysfunction) [7, 32, 55, 59]. Various TRP subtypes act as cell sensors for changes in redox status, [1, 23, 63] including TRPM2 [23, 43], TRPV1 [63], TRPC5 [61] and TRPA1 [25, 35, 54], thus highlighting TRP channels as frequent targets of oxidative modification. Oxidative modulation of TRPV1 involves modification of numerous residues, including cysteine(s), participating in various intra- and inter-subunit bonds which could contribute to overall TRPV1 activity via changes in reaction kinetics and stability. These intrinsic differences in gating mechanisms in response to oxidants suggest TRPV1 may act as a broad sensor of oxidant concentrations over a sustained period [9]. TRPV1 residues susceptible to oxidation may have specific ranges of regulation, thus it is conceivable that these modified residues control TRPV1 channel activity under cellular redox conditions in order to gate the channel appropriately. Recently, cytoplasmic C-terminus cysteine residues that sensitize TRPV1 activation upon oxidative challenge have been identified [9]. Furthermore, Jin and co-workers [28] demonstrated the ability of the oxidizing agent thimerosal to decrease TRPV1 activity via oxidation of extracellular sulfhydryl residues (Cys621). TRPV1 contains numerous cysteine residues [13] that could potentially be involved in redox modulation As the thiol moieties are sensitive to oxidation yielding various reversible products [60]. Reactive thiols are known to alter protein function whenever sulfhydryls are involved in catalysis or modulation of activity, thus representing a unique mechanism by which disease states interfere with protein function. Oxidation of individual thiol proteins have been observed in hearts or myocytes subjected to oxidative stress [8, 30, 51]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that exogenous H2O2 causes oxidation of cysteine residues and potentiates heat-evoked membrane currents in HEK293T cells [52], an effect mediated by the TRPV1 channel. However, we do not know if H2O2 exerts its effects on TRPV1 by modifying these residues. But our results with DTT suggest that H2O2 mediates its effect on TRPV1 via modifying cysteine residues. We believe the actions of DTT to be a combination of action on both TRPV1 and KV channels as others [47, 52] have demonstrated a role for modulatory effects of DTT on both channels. However, a significant difference relating in particular to the Susankova et al., (2006) findings relate to the amount of DTT used to establish its effects on TRPV1 versus the current manuscript (10 mM DTT Susankova study vs. 10 μM current study). Furthermore, both reducing and oxidizing agents facilitate membrane currents induced by noxious heat and capsaicin through the oxidation of extracellular [52, 57] and intra-cellular cysteine residues of the TRPV1 receptor [52]. Similarly, oxidation of cysteine residues modulates the activity of ATP-sensitive K+ channels [41] and BK channels [14], among others. Future studies will examine the oxidative modification of TRPV1 by H2O2.

The ability and extent to which coronary TRPV1 channels may translate oxidant stimuli into vasoactive signaling cascades is of particular interest and could provide insight into the effects of prolonged exposure of TRPV1 to oxidative stress. Our data highlight the rationale that as diabetic dysfunction progresses, oxidative stress increases and subsequent exposure to higher concentrations of ROS for prolonged durations enhances the potential for abnormal vascular TRPV1 signaling. This ROS imbalance can be detrimental to the cellular environment leading to oxidative posttranslational modification (PTM) of proteins. Alterations in cellular redox status can lead to aberrant PTM and corresponding pathological changes in protein function [12, 39]. Importantly, the plasma concentration of H2O2 in humans were reported to be between 1 and 35 μM [22]. Interestingly, H2O2 plasma concentration was demonstrated to be 50 nmol MDA/ml in control mice and 100 nmol MDA/ml in diabetic mice [17] suggesting that diabetes increases H2O2 levels in plasma.

Oxidative environments also reduce capsaicin-evoked TRPV1 currents due to decreased effective agonist concentration caused by chemical reactions between capsaicin and oxidants [27, 52]. The current study details H2O2-dependent changes in coronary vascular reactivity seen in WT mice are significantly altered in coronary microvessels isolated from db/db mice. This is evident when prolonged luminal exposure to 100 nM H2O2 in isolated coronary microvessels from WT mice markedly attenuated capsaicin-mediated dilation responses when compared to baseline. Similarly, prolonged H2O2 exposure markedly attenuated CBF increases to capsaicin and led to decreased TRPV1-mediated currents. In db/db mice, prolonged H2O2 exposure led to minimal changes in capsaicin-mediated effects (changes in CBF or relaxation), suggesting TRPV1 was already desensitized in this diabetic state. Thus further exposure of these already desensitized channels to even further oxidative stress conditions had little, if any, effect. Oxidative stress-induced TRPV1 diminished functional expression may underlie, at least in part, the diabetic coronary microvascular complications often seen in patients and in animal models of diabetic microvascular dysfunction.

Oxidation may represent a pathway independent of phosphorylation, desensitization, and acidic pH, acting to regulate TRPV1 channel activity. Changes in oxidative stress, leading to TRPV1 channel aberrant function, may promote the onset and development of diseases, as modifications in the function of these modulated TRPV1 channels have been associated with cell dysfunction and human pathologies [45, 65]. Although we did not measure the cell-specific contribution of TRPV1 (endothelial vs smooth muscle), our ex vivo isolated vessel studies and in vivo blood flow measurements in WT and global V1KO mice clearly demonstrate a critical role of TRPV1 in the regulation of coronary blood flow. Although coronary blood flow changes evoked by H2O2 are almost completely blunted in V1KO mice, the interpretation of these results are certainly confounded by the potential effects H2O2 has in vivo on the cardiovascular system. One must take into account the effect TRPV1 deletion may have on systemic parameters which in turn affect CBF. Based on our previous studies, we believe that endothelial TRPV1 accounts for the observed changes in the present study, however, a cell-specific V1KO mouse may unequivocally answer the contribution of endothelial or VSMC TRPV1 in coronary blood flow regulation which is the focus of our future studies.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the physiological importance of H2O2 regulation of TRPV1 dependent modulation of CBF. Our results provide evidence that the actions of redox-active substances such as H2O2 are likely mediated by reduction and oxidation of specific sites on TRPV1. The subsequent modification(s) may have consequences for TRPV1 activity and thus represent a mechanism for the regulation of TRPV1 under both physiological and pathophysiological states. The modulation of TRPV1 by oxidizing agents will continue to reveal the numerous mechanisms that regulate TRPV1 activity during oxidant-induced microvascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by Dr. Bratz's Start-up funds provided by NEOMED and NIH grant HL83237 (Yeong-Renn Chen).

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards: Conflict of interest On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material: The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00395-016-0539-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Aarts M, Iihara K, Wei WL, Xiong ZG, Arundine M, Cerwinski W, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M. A key role for TRPM7 channels in anoxic neuronal death. Cell. 2003;115:863–877. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barlow RS, El-Mowafy AM, White RE. H(2)O(2) opens BK(Ca) channels via the PLA(2)-arachidonic acid signaling cascade in coronary artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H475–H483. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow RS, White RE. Hydrogen peroxide relaxes porcine coronary arteries by stimulating BKCa channel activity. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1283–H1289. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beny JL, von der Weid PY. Hydrogen peroxide: an endogenous smooth muscle cell hyperpolarizing factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176:378–384. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(91)90935-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogeski I, Kappl R, Kummerow C, Gulaboski R, Hoth M, Niemeyer BA. Redox regulation of calcium ion channels: chemical and physiological aspects. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:407–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bratz IN, Dick GM, Tune JD, Edwards JM, Neeb ZP, Dincer UD, Sturek M. Impaired capsaicin-induced relaxation of coronary arteries in a porcine model of the metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2489–H2496. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01191.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busik JV, Mohr S, Grant MB. Hyperglycemia-induced reactive oxygen species toxicity to endothelial cells is dependent on paracrine mediators. Diabetes. 2008;57:1952–1965. doi: 10.2337/db07-1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CL, Zhang L, Yeh A, Chen CA, Green-Church KB, Zweier JL, Chen YR. Site-specific S-glutathiolation of mitochondrial NADH ubiquinone reductase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5754–5765. doi: 10.1021/bi602580c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuang HH, Lin S. Oxidative challenges sensitize the capsaicin receptor by covalent cysteine modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20097–20102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902675106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark SG, Fuchs LC. Role of nitric oxide and Ca ++-dependent K + channels in mediating heterogeneous microvascular responses to acetylcholine in different vascular beds. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:1473–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman HA, Tare M, Parkington HC. Endothelial potassium channels, endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization and the regulation of vascular tone in health and disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31:641–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutler MJ, Plummer BN, Wan X, Sun QA, Hess D, Liu H, Deschenes I, Rosenbaum DS, Stamler JS, Laurita KR. Aberrant S-nitrosylation mediates calcium-triggered ventricular arrhythmia in the intact heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:18186–18191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210565109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhaka A, Uzzell V, Dubin AE, Mathur J, Petrus M, Bandell M, Patapoutian A. TRPV1 is activated by both acidic and basic pH. J Neurosci. 2009;29:153–158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4901-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiChiara TJ, Reinhart PH. Redox modulation of hslo Ca2+-activated K+ channels. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4942–4955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-04942.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M, Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao YJ, Lee RM. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium-dependent contracting factor in rat renal artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;146:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giordano FJ. Oxygen, oxidative stress, hypoxia, and heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:500–508. doi: 10.1172/JCI24408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griendling KK. NADPH oxidases: new regulators of old functions. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1443–1445. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guarini G, Ohanyan VA, Kmetz JG, DelloStritto DJ, Thoppil RJ, Thodeti CK, Meszaros JG, Damron DS, Bratz IN. Disruption of TRPV1-mediated coupling of coronary blood flow to cardiac metabolism in diabetic mice: role of nitric oxide and BK channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H216–H223. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00011.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halliwell B, Clement MV, Long LH. Hydrogen peroxide in the human body. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:10–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02197-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara Y, Wakamori M, Ishii M, Maeno E, Nishida M, Yoshida T, Yamada H, Shimizu S, Mori E, Kudoh J, Shimizu N, Kurose H, Okada Y, Imoto K, Mori Y. LTRPC2 Ca2 + -permeable channel activated by changes in redox status confers susceptibility to cell death. Mol Cell. 2002;9:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiett SC, Owen MK, Li W, Chen X, Riley A, Noblet J, Flores S, Sturek M, Tune JD, Obukhov AG. Mechanisms underlying capsaicin effects in canine coronary artery: implications for coronary spasm. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:607–618. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinman A, Chuang HH, Bautista DM, Julius D. TRP channel activation by reversible covalent modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19564–19568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609598103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jay D, Hitomi H, Griendling KK. Oxidative stress and diabetic cardiovascular complications. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin X, Morsy N, Winston J, Pasricha PJ, Garrett K, Akbarali HI. Modulation of TRPV1 by nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, c-Src kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C558–C563. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00113.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin Y, Kim DK, Khil LY, Oh U, Kim J, Kwak J. Thimerosal decreases TRPV1 activity by oxidation of extracellular sulfhydryl residues. Neurosci Lett. 2004;369:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaneto H, Katakami N, Matsuhisa M, Matsuoka TA. Role of reactive oxygen species in the progression of type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:453892. doi: 10.1155/2010/453892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar V, Kitaeff N, Hampton MB, Cannell MB, Winterbourn CC. Reversible oxidation of mitochondrial peroxiredoxin 3 in mouse heart subjected to ischemia and reperfusion. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lacza Z, Puskar M, Kis B, Perciaccante JV, Miller AW, Busija DW. Hydrogen peroxide acts as an EDHF in the piglet pial vasculature in response to bradykinin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H406–H411. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00007.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li JM, Shah AM. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1014–R1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00124.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Gutterman DD. The coronary circulation in diabetes: influence of reactive oxygen species on K + channel-mediated vasodilation. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;38:43–49. doi: 10.1016/S1537-1891(02)00125-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma L, Zhong J, Zhao Z, Luo Z, Ma S, Sun J, He H, Zhu T, Liu D, Zhu Z, Tepel M. Activation of TRPV1 reduces vascular lipid accumulation and attenuates atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;92:504–513. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macpherson LJ, Dubin AE, Evans MJ, Marr F, Schultz PG, Cravatt BF, Patapoutian A. Noxious compounds activate TRPA1 ion channels through covalent modification of cysteines. Nature. 2007;445:541–545. doi: 10.1038/nature05544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matoba T, Shimokawa H, Kubota H, Morikawa K, Fujiki T, Kunihiro I, Mukai Y, Hirakawa Y, Takeshita A. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in human mesenteric arteries. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:909–913. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matoba T, Shimokawa H, Nakashima M, Hirakawa Y, Mukai Y, Hirano K, Kanaide H, Takeshita A. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1521–1530. doi: 10.1172/JCI10506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Gaber M, Hainer J, Klein J, Dorbala S, Blankstein R, Di Carli MF. Association between coronary vascular dysfunction and cardiac mortality in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2012;126:1858–1868. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.120402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura T, Tu S, Akhtar MW, Sunico CR, Okamoto S, Lipton SA. Aberrant protein s-nitrosylation in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron. 2013;78:596–614. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilius B, Talavera K, Owsianik G, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Voets T. Gating of TRP channels: a voltage connection? J Physiol. 2005;567:35–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park MK, Bae YM, Lee SH, Ho WK, Earm YE. Modulation of voltage-dependent K+ channel by redox potential in pulmonary and ear arterial smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. Pflugers Arch. 1997;434:764–771. doi: 10.1007/s004240050463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park SW, Noh HJ, Sung DJ, Kim JG, Kim JM, Ryu SY, Kang K, Kim B, Bae YM, Cho H. Hydrogen peroxide induces vasorelaxation by enhancing 4-aminopyridine-sensitive Kv currents through S-glutathionylation. Pflugers Arch. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1513-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perraud AL, Takanishi CL, Shen B, Kang S, Smith MK, Schmitz C, Knowles HM, Ferraris D, Li W, Zhang J, Stoddard BL, Scharenberg AM. Accumulation of free ADP-ribose from mitochondria mediates oxidative stress-induced gating of TRPM2 cation channels. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6138–6148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Randhawa PK, Jaggi AS. TRPV4 channels: physiological and pathological role in cardiovascular system. Basic Res Cardiol. 2015;110:5. doi: 10.1007/s00395-015-0512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Robbins N, Koch SE, Rubinstein J. Targeting TRPV1 and TRPV2 for potential therapeutic interventions in cardiovascular disease. Transl Res. 2013;161:469–476. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roe ND, Thomas DP, Ren J. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase alleviates experimental diabetes-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:465–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rogers PA, Chilian WM, Bratz IN, Bryan RM, Jr, Dick GM. H2O2 activates redox- and 4-aminopyridine-sensitive Kv channels in coronary vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1404–H1411. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00696.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rogers PA, Dick GM, Knudson JD, Focardi M, Bratz IN, Swafford AN, Jr, Saitoh S, Tune JD, Chilian WM. H2O2-induced redox-sensitive coronary vasodilation is mediated by 4-aminopyridine-sensitive K+ channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2473–H2482. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00172.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saitoh S, Zhang C, Tune JD, Potter B, Kiyooka T, Rogers PA, Knudson JD, Dick GM, Swafford A, Chilian WM. Hydrogen peroxide: a feed-forward dilator that couples myocardial metabolism to coronary blood flow. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2614–2621. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000249408.55796.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sawada Y, Hosokawa H, Matsumura K, Kobayashi S. Activation of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 by hydrogen peroxide. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:1131–1142. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schroder E, Brennan JP, Eaton P. Cardiac peroxiredoxins undergo complex modifications during cardiac oxidant stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H425–H433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00017.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Susankova K, Tousova K, Vyklicky L, Teisinger J, Vlachova V. Reducing and oxidizing agents sensitize heat-activated vanilloid receptor (TRPV1) current. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:383–394. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szallasi A, Cortright DN, Blum CA, Eid SR. The vanilloid receptor TRPV1: 10 years from channel cloning to antagonist proof-of-concept. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:357–372. doi: 10.1038/nrd2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takahashi N, Mizuno Y, Kozai D, Yamamoto S, Kiyonaka S, Shibata T, Uchida K, Mori Y. Molecular characterization of TRPA1 channel activation by cysteine-reactive inflammatory mediators. Channels (Austin) 2008;2:287–298. doi: 10.4161/chan.2.4.6745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ushio-Fukai M, Tang Y, Fukai T, Dikalov SI, Ma Y, Fujimoto M, Quinn MT, Pagano PJ, Johnson C, Alexander RW. Novel role of gp91(phox)-containing NAD(P)H oxidase in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced signaling and angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2002;91:1160–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000046227.65158.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Victor VM, Rocha M, Herance R, Hernandez-Mijares A. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:3947–3958. doi: 10.2174/138161211798764915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vyklicky L, Lyfenko A, Kuffler DP, Vlachova V. Vanilloid receptor TRPV1 is not activated by vanilloids applied intracellularly. NeuroReport. 2003;14:1061–1065. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000073429.02536.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang P, Yan Z, Zhong J, Chen J, Ni Y, Li L, Ma L, Zhao Z, Liu D, Zhu Z. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 activation enhances gut glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion and improves glucose homeostasis. Diabetes. 2012;61:2155–2165. doi: 10.2337/db11-1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wassmann S, Wassmann K, Nickenig G. Regulation of antioxidant and oxidant enzymes in vascular cells and implications for vascular disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2006;8:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s11906-006-0043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Winterbourn CC, Hampton MB. Thiol chemistry and specificity in redox signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45:549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu SZ, Sukumar P, Zeng F, Li J, Jairaman A, English A, Naylor J, Ciurtin C, Majeed Y, Milligan CJ, Bahnasi YM, Al-Shawaf E, Porter KE, Jiang LH, Emery P, Sivaprasadarao A, Beech DJ. TRPC channel activation by extracellular thioredoxin. Nature. 2008;451:69–72. doi: 10.1038/nature06414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yada T, Shimokawa H, Hiramatsu O, Kajita T, Shigeto F, Goto M, Ogasawara Y, Kajiya F. Hydrogen peroxide, an endogenous endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor, plays an important role in coronary autoregulation in vivo. Circulation. 2003;107:1040–1045. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000050145.25589.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yoshida T, Inoue R, Morii T, Takahashi N, Yamamoto S, Hara Y, Tominaga M, Shimizu S, Sato Y, Mori Y. Nitric oxide activates TRP channels by cysteine S-nitrosylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:596–607. doi: 10.1038/nchembio821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang DX, Borbouse L, Gebremedhin D, Mendoza SA, Zinkevich NS, Li R, Gutterman DD. H2O2-induced dilation in human coronary arterioles: role of protein kinase G dimerization and large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel activation. Circ Res. 2012;110:471–480. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang LL, Yan LD, Ma LQ, Luo ZD, Cao TB, Zhong J, Yan ZC, Wang LJ, Zhao ZG, Zhu SJ, Schrader M, Thilo F, Zhu ZM, Tepel M. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid type-1 channel prevents adipogenesis and obesity. Circ Res. 2007;100:1063–1070. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000262653.84850.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.