Abstract

The current study examined the potential for mental health to mediate associations between earlier attachment to parents and peers and later relationship adjustment during adolescence and young adulthood in a sample of sexual minority youth. Secondarily, the study examined associations between peer and parental attachment and relationship/dating milestones. Participants included 219 lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth who participated in six waves of data collection over 3.5 years. Parental attachment was associated with an older age of dating initiation, while peer attachment was associated with longer relationship length. Both peer and parental attachment were significantly associated with mental health in later adolescence and young adulthood. Mental health mediated the association between peer attachment and main partner relationship quality. While the total indirect effect of parental attachment on main partner relationship quality was statistically significant, specific indirect effects were not. Implications for the application of attachment theory and integration of interpersonal factors into mental health intervention with sexual minority youth are discussed.

Keywords: gay/lesbian/bisexual, parental attachment, peer attachment, relationship quality, sexual development

INTRODUCTION

Being in a primary relationship is a common experience shared by many adults in the U.S. Data from the United States Census Bureau indicated that only 44% of US residents age 18 or older were unmarried in 2013 (US Census Bureau, 2014). Additionally, estimates from 2012 census data suggest that as many as seven million US households were comprised unmarried partners (US Census Bureau, 2014). The salience of partnering is evident in the fact that it has been addressed directly in many developmental theories (e.g., Bowlby, 1977; Erikson, 1980; Maag, 2006). Such theories often situate the initiation of primary partnerships in late adolescence or early adulthood. For example, Erikson’s (1980) theory of psychosocial development posited that the establishment of intimacy — “the capacity to commit oneself to concrete affiliations which may call for significant sacrifices and compromises” (p. 70) — becomes the salient developmental task as individuals emerge from adolescence into young adulthood.

In establishing primary relationships as adolescents and young adults, individuals bring with them a learning history that shapes their behavioral repertoire and expectancies. Attachment theory (Ainsworth, 1985; Bowlby, 1977) posits that individuals form internal working models of the self (as acceptable/lovable or not) and others (as safe/available/reliable or not). These working models are initially constructed based upon early interactions between infants and caregivers. The security of attachment has been commonly construed as the degree to which an individual perceives him/herself as lovable/acceptable and others as safe and available. In this framework, secure attachment is characterized by positive working models of the self and others. Insecure forms of attachment are characterized by internal working models in which others are viewed to some degree as unreliable and/or the self is viewed as unacceptable or undesirable to others (Ainsworth, 1985; Bowlby, 1977).

Erikson (1980) suggested that the maladaptive resolution of earlier developmental crises could complicate the healthy resolution of challenges in later stages. Similarly, attachment theory posits that across the life-span, secure attachments to parents and caregivers are associated with the security of later attachments to peers and romantic partners (Ainsworth, 1985; Bowlby, 1977). Research examining the developmental continuity of relationship quality across different kinds of relationships (e.g., attachment to parents, peers, and romantic partners) supports this proposition. Secure attachment to parents has been associated with more secure attachment to peers and greater intimate partner relationship quality later in life (Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Collins & Read, 1990; Mehta, Cowan, & Cowan, 2009).

To date, research on the developmental continuity of attachment has focused primarily on heterosexual samples. Sexual minority individuals (including lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, questioning, and same-sex loving individuals) face unique barriers to the establishment of interpersonal expectancies consistent with secure attachment. Because of their sexual orientation, they are more likely to both anticipate rejection (Pachankis, Goldfried, & Ramrattan, 2008) and to experience rejection from parents (Baiocco et al., 2015), particularly during early stages of the coming out process (D’Augelli, 2006). Data suggest that experiences of rejection from peers are also common for sexual minority youth. Kosciw, Greytak, Palmer, and Boesen (2013) surveyed 7,898 sexual minority and transgender students in the US between the ages of 13 and 21. They found that 74.1% reported verbal harassment, 36.2% reported physical harassment, 16.5% reported physical assault, and 55.5% felt unsafe at school because of their sexual orientation in the past year. This lack of support may increase social isolation and reinforce existing negative self-image (Rosario, Schrimshaw, & Hunter, 2009) in a manner that enhances the likelihood of developing expectancies consistent with insecure attachment and decreases the likelihood of encountering social interactions that would challenge these expectancies.

Understanding associations among parental attachment, peer attachment, and primary partner relationship quality for sexual minority youth has public health significance. All three constructs have been linked to mental and sexual health problems which disproportionately impact sexual minority individuals. We briefly review this literature before moving on to outline hypothesized developmental pathways linking attachment and relationship quality. Note, when discussing correlates of attachment to parents and/or peers in sexual minority youth specifically, it is potentially useful to differentiate between the security of attachment (the degree of closeness or emotional connection in a relationship) and acceptance or support for a sexual minority identity. While some data indicate that perceptions of closeness and perceptions of acceptance are related (Floyd, Stein, Harter, Allison, & Nye, 1999), these two constructs are meaningfully different. Acceptance of an adolescent’s sexual minority identity does not guarantee that a relationship is emotionally close. Similarly, adolescents may have powerful emotional connections to people who (would) have difficulty accepting their sexual minority identity.

Sexual minority individuals face high rates of mental health problems, including increased rates of anxiety disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress symptoms, self-injurious behavior, and suicidal ideation and behaviors (Liu & Mustanski, 2012; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Hatzenbuehler (2009) highlighted the link between the quality of interpersonal relationships and mental health. He concluded that disruptions in important social/interpersonal relationships are one of three mechanisms by which experiences of stigma result in mental health disparities for sexual minority populations. Evidence supports the conclusion that the quality of attachment relationships is meaningfully related to psychological well-being beginning in adolescence (Darby-Mullins & Murdock, 2007; Holtzen, Kenny, & Mahalik, 1995; Savin-Williams, 1989). Darby-Mullins and Murdock (2007) found that general family functioning (a construct consistent with formulations of parental attachment) was a significant predictor of emotional adjustment among sexual minority youth, even when positive parental attitudes toward homosexuality were included in the model.

In addition to mental health correlates, the quality of attachment relationships has been associated with indicators of sexual health in adolescence. In studies of adolescents not restricted by sexual orientation, those who reported stronger attachment to parents also reported an older age at first sexual intercourse, fewer sexual partners (Ackard, Fedio, Neumark-Sztainer, & Britt, 2008; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012), and lower risk of STIs (Ford et al., 2005). Less is known about sexual minority youth specifically. While Ackard et al. (2008) and Ford et al. (2005) included sexual minority youth as part of their samples, no studies have examined the role of parent-child connectedness and sexual or dating history among sexual minority youth specifically (Bouris et al., 2010). Similarly, research related to peer attachment has found that close connection to a peer group in which norms promote engagement in sex is associated with earlier sexual debut (Sieving, Eisenberg, Pettingell, & Skay, 2006).

Similar to attachment, primary partner relationship quality has been linked to both mental and sexual health outcomes for individuals in relationships. Frost and Meyer (2009) found that depression was positively associated with relationship problems in a sample of gay, lesbian and bisexual individuals. Data from lesbian women indicate that their mental health was significantly associated with their partner’s report of relationship satisfaction (Otis, Riggle, & Rostosky, 2006). Davidovich, De Wit, and Stroebe (2006) found that low relationship satisfaction and low relationship commitment predicted more sexual risk-taking and diminished use of negotiated safety as a harm reduction strategy in their sample of gay men in steady relationships. Similarly, Mitchell, Harvey, Champeau, and Seal (2012) surveyed partnered gay and bisexual men and found that greater commitment to a sexual agreement was associated with less sexual risk-taking.

To date, no studies have examined developmental pathways connecting attachment expectancies with relationship outcomes among sexual minority individuals. At least two potential pathways may be hypothesized. The first of these is derived from assumptions within attachment theory. The second is derived from data linking attachment style with mental health and mental health to main partner relationship quality. We briefly provide a rationale for each of these pathways below.

Based upon assumptions of attachment theory, one would hypothesize that secure attachment to parents increases the likelihood of secure attachments to peers. Interactions with peers then further inform the content of established working models and shape behavior in subsequent romantic relationships such that youth with more secure peer attachments establish higher quality romantic relationships. Evidence from research on heterosexual youth supports the plausibility of such a pathway. Furman, Simon, Shaffer, and Bouchey (2002) found that peer attachment was consistently associated with parental attachment and to romantic relationship quality; however, the direct connection between parental attachment and romantic relationship quality was inconsistent.

Available evidence suggests that a second pathway between early attachment to parents and later relationship quality may exist through associations with mental health. As discussed above, disruptions in interpersonal relationships have been implicated in the emergence of mental health problems (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). Consistent with this, studies of adult attachment have demonstrated that attachment security is negatively associated with depression as well as anxiety (Shidlo, 1994; Simonelli, Ray, & Pincus, 2004; Steffens, 2005). In turn, these same aspects of mental health predicted by attachment style have been linked to diminished main partner relationship quality (Frost & Meyer, 2009; Keelan, Dion, & Dion, 1998; Otis et al., 2006; Seifer, Schiller, Sameroff, Resnick, & Riordan, 1996). Taken together, these findings suggest that the association between attachment and relationship quality may be explained in part by associations with mental health.

The existing literature is characterized by a lack of knowledge about developmental associations among attachment to parents, attachment to peers, and primary partner relationship quality among sexual minority individuals. Secondarily, the existing literature examining mental and sexual health correlates of peer and parental attachment has not examined such associations in sexual minority youth specifically. A related limitation is that the available research related to sexual correlates of attachment has examined the influence of peer and parental relationships on sexual debut and aspects of sexual risk-taking among adolescents. While useful, these studies have generally focused on sexual behavior variables. Less attention has been paid to other aspects of relationship history (onset of dating behavior, relationship length, etc.). These kinds of relationship milestones may be important in understanding how attachment becomes linked with primary partner relationship quality.

The current study had three goals, all of which were longitudinal in nature. The first was to explore associations between attachment to peers and parents in earlier adolescence with relationship milestones in later adolescence among sexual minority youth. The second was to test whether earlier adolescent parental attachment and peer attachment are associated with general mental health during later adolescence. Finally, the study tested the significance of hypothesized indirect pathways linking attachment to parents and peers in early adolescence with main partner relationship quality in later adolescence and early adulthood. To achieve these goals, the study utilized longitudinal data from six waves of data collection spanning a 3.5-year period. The primary predictors of interest, attachment to peers and parents, were assessed during the first three waves of data collection (baseline, 6-, and 12-month follow-up). Relationship outcome data were gathered in later waves. Data related to the primary outcome of interest, romantic relationship quality, come from the final three waves of data collection. Meanwhile, data on relationship milestones were gathered only at the final follow-up. Finally, data related to global mental health in later adolescence, a hypothesized mediator, came from the final four waves of data collection.

METHOD

Participants

A total of 248 lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth from the Chicago area (identified as ages 16–20 years at baseline) were recruited into the study. Of these, 12 youth identified as transgender female and eight identified as transgender male. An additional seven participants reported a gender identity that was different from their sex assigned at birth and two participants did not respond to the gender identity question. Developmental research indicates the transgender identified youth may experience unique stressors in interpersonal relationships generally and their sexual identity development specifically (Bockting, Benner, & Coleman, 2009; Devor, 2004; Garofalo, Deleon, Osmer, Doll, & Harper, 2006; Morgan & Stevens, 2008). Because the available sample size did not permit an examination of transgender youth as a distinct category, the analytic sample therefore included 219 sexual minority youth who identified their gender as male or female and were assigned a corresponding sex at birth.

Approximately half of the sample reported a female gender identity (46.6%). The largest percentage of sexual minority youth identified as Black/African-American (56.6%), followed by White (13.7%), Latino/Hispanic (13.2%), and Other/Multiracial (16.4%). In terms of self-reported sexual orientation at baseline interview, 62.1% identified as gay or lesbian, 31.1% identified as bisexual, and 6.8% identified as heterosexual or in some other way (i.e., questioning, queer, unsure). Mean age of the analytic sample at baseline was 18.8 (SD = 1.49) and 34.2% were under age 18. Of note, participants self-reported age at baseline, but identification checks conducted at later waves of data collection resulted in an adjusted mean age compared with previous reports. Table 1 displays demographic characteristics of the analytic sample.

Table 1.

Analytic sample demographic characteristics

| Demographics | Total N = 219 |

|---|---|

|

| |

|

n (%)

|

|

| Gender | |

| Male | 117 (53.4) |

| Female | 102 (46.6) |

| Sexual Identity | |

| Lesbian/Gay | 136 (62.1) |

| Bisexual | 68 (31.1) |

| Heterosexual/Questioning/Unsure | 15 (6.8) |

| Race and Ethnicity | |

| Black/African American | 124 (56.6) |

| White/European | 30 (13.7) |

| Latino/a | 29 (13.2) |

| Other/Multiracial | 36 (16.4) |

Procedure and Design

We employed an accelerated longitudinal design involving six follow-ups over 3.5 years (Tonry, Ohlin, & Farrington, 1991). A modified respondent-driven sampling approach (Heckathorn, 1997) was used for recruitment that involved an initial convenience sample (i.e., flyers in LGBT neighborhoods and college listservs; 38%) and subsequent waves of incentivized peer recruitment (62%). Participants were paid $25 - $40 for participation at each time point. At each visit, participants completed self-report measures of health behaviors, mental health, and psychosocial variables. Data for analyses were from six waves (2007–2012; baseline and 6-, 12-, 18-, 24-, and 42-month follow-up), and retention at each wave was 85, 90, 79, 77, and 82%, respectively. Retention rates may differ from previous reports based on differences between analytic samples. The Institutional Review Boards approved this protocol.

Measures

Demographics

The demographics questionnaire assessed participant age, birth sex, gender identity, race/ethnicity, self-reported sexual orientation, living situation, and education. All models accounted for gender identity (male coded = 0 and female coded = 1), race (Black, White, Latino, and Other/Multiracial), and participant age at time point.

Psychosexual Developmental Milestones

Based on the work of Kuttler and La Greca (2004), we administered several questions at the 42-month follow-up wave assessing dating history and current level of dating involvement. Four of these questions were included in these analyses: (1) “How old were you when you first started dating?”; (2) “How long do your serious relationships tend to last? (in months)”; (3) “How many dating partners have you had in your life?”; and (4) “Thinking of all the people you have dated in your life, how many were serious partners?” Participants provided numeric responses to each of these questions.

Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment

Adolescents’ perceptions of the psychological security of the relationships with their parents and close friends was assessed using a shortened version of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Raja, McGee, & Stanton, 1992). The scale is comprised of 24 items, which are divided across subscales assessing parent and peer attachment. The IPPA was administered at baseline, 6- and 12-month follow-up. Cronbach’s alpha in this sample ranged from .84 to .88 for the peer attachment subscale and from .88 to .99 for the parent attachment subscale.

Disclosure Issues Scale

Based on the work of D’Augelli, Hershberger, and Pilkington (1998), we administered two items assessing disclosure of same-sex orientation and acceptance of sexual orientation by important individuals in participants’ lives at the 18 month assessment point. These analyses utilized the acceptance item, which asked participants to indicate whether each individual listed (e.g., parents, other family, friends) is (or would be) accepting of the participant’s sexual orientation: “How has each of the following persons reacted (or how do you think they would react) to the fact that you are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender?” Response options include: “accepting (it would not matter)”; “tolerant (but not accepting)”; “intolerant (but not rejecting)”; and “rejecting”. To capture parental acceptance, we created a dichotomous variable in which “1” indicated that either the participant’s mother or father was (or was anticipated to be) accepting, and “0” indicated that neither was (nor was anticipated to be) accepting. Similarly, we created a dichotomous variable for friend acceptance in which “1” indicated that either the participant’s closest female friend or closest male friend was (or was anticipated to be) accepting, and “0” indicated that neither was (nor was anticipated to be) accepting.

Brief Symptom Inventory

The Global Severity Index (GSI) of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI 18) (Derogatis, 2000) is a self-report measure of psychological distress during the previous week. The BSI 18 is a widely used psychiatric screening tool in epidemiological studies and clinical settings. It has adequate reliability and convergent validity with the longer version and related measures (Zabora et al., 2001). For these analyses, we used GSI scores from the 12-, 18-, 24-, and 42-month follow-ups, which demonstrated strong internal consistency across these waves (Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .93 to .94).

Relationship Assessment Scale

The Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS) is a 7-item measure of relationship satisfaction (Hendrick, 1988). Satisfaction is measured for each item as rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “low satisfaction” to “high satisfaction”. Example items include: “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?” and “How much do you love your partner?” The RAS has strong reliability and validity, and it correlates highly with the widely used Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976). Participants completed this measure based on positive endorsement of the following item: “Are you currently in a romantic relationship with anyone, or have you been in a romantic relationship with anyone within the last 6 months?” If participants responded “yes” to this item, they were asked whether the relationship was a current or previous relationship (i.e., most recent relationship in past six months). The RAS demonstrated strong internal consistency at these waves (Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .85 to .89).

For these analyses, we used RAS scores for all individuals who indicated a current or past 6-month relationship at the 12-, 24-, and 42-month follow-ups. A total of 150 participants included in the analytic sample reported on a current relationship during at least one of the assessment periods. For these participants, their RAS ratings for the current relationship were used. If they reported currently being in a relationship at more than one time point, these responses were averaged. An additional 27 youth reported on past-6-month relationship during at least one assessment period, but no current relationships were reported. In these instances, RAS scores for past-6-month relationships were used. Where participants reported being in a terminated relationship during the past 6 months at multiple follow-up time points, responses were averaged. The remaining 42 participants did not complete the RAS at the 12-, 24-, and 42-month follow-ups. Of these, 15 participants never completed a 12-, 24-, or 42-month follow-up. The other 27 participants completed at least one of these follow-up appointment but were not in a relationship currently or in the 6 months prior to follow-up.

Analytic Plan

The bivariate association between sexual developmental milestones (assessed at the 42-month follow-up) and parental and peer attachment (reported at baseline) was evaluated using independent samples t-tests. Sexual development milestone variables were all dichotomized and utilized as the independent variable.

The association between attachment (peer and parental) and global mental health trajectories was assessed in a latent growth curve model estimated in Mplus v7.1. Intercept and slope factors were specified for parental attachment, peer attachment, and global mental health. In an initial step, slope factors were evaluated to determine the utility of their inclusion in subsequent models. In instances where the average slope and the variance of the slope were both non-significant (i.e., they did not differ significantly from zero), the slope factor was dropped from the model and only an intercept, representing the average score across assessment points, was modeled. The presence of a slope factor with a mean and variance equivalent to zero implies that, on average, participants did not change significantly over time and that individual variability in change over time was negligible. Following this initial step, retained growth factors for global mental health scores were then regressed on retained growth factors for parental and peer attachment. Parental acceptance, friend acceptance, age, gender, and race were included as covariates in the model predicting the slope and intercept of mental health scores.

Finally, a latent growth model was utilized to test the hypothesis that global mental health would mediate a pathway between attachment (peer and parental) and relationship adjustment. Bootstrapping tests of mediation were utilized to evaluate the significance of the indirect pathway. These analyses were restricted to participants who reported being in a current relationship or having a relationship in the past 6 months during at least one of the 12-, 24-, and 42-month follow-ups. The purpose in this decision was to focus the analyses on factors associated with relationship quality among adolescents who were known to be engaging in relationships. The imputation of RAS scores for participants who reported no partners at any follow-up runs the risk of blurring potentially meaningful qualitative distinctions between youth who do not engage in relationships at all and those who have at least some relationship engagement.

RESULTS

Relationship history and attachment to parents and peers

Table 2 contains the results of independent samples t-tests examining relationship milestone differences in reported parental and peer attachment scores reported at baseline. Participants who reported dating initiation at age 15 or older reported significantly higher parental attachment scores than those who reported the initiation of dating at age 14 or younger. Participants who reported an average relationship length of 13 months or longer reported higher peer attachment on average than those who reported an average relationship length of a year or less. Number of dating partners and number of serious dating partners were not associated with parental or peer attachment. Note, the effect of missingness on results was evaluated by re-analyzing data using FIML estimation. The results were essentially unchanged from those presented.

Table 2.

Relationship history and attachment to peers and parents

|

|

Parental Attachment

|

Peer Attachment

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | M (SD) | Test statistic | M (SD) | Test statistic | |

|

|

|

|

|||

| Dating initiation age | t (166) = −2.27* | t (166) = −0.61 | |||

| 14 or less | 60 (35.7) | 35.1 (10.0) | 47.3 (7.7) | ||

| 15 or more | 108 (64.3) | 38.9 (10.8) | 48.0 (8.1) | ||

| Average relationship length | t (166) = −0.62 | t (166) = −3.02** | |||

| 12 months or less | 102 (60.7) | 37.2 (9.9) | 46.3 (8.2) | ||

| 13 months or more | 66 (39.3) | 38.2 (11.7) | 50.0 (7.1) | ||

| Total dating partners | t (166) = 0.82 | t (166) = −0.96 | |||

| 5 or less | 86 (51.2) | 38.2 (10.6) | 47.2 (8.5) | ||

| 6 or more | 82 (48.8) | 36.8 (10.7) | 48.4 (7.4) | ||

| Total serious partners | t (166) = −0.37 | t (166) = −1.36 | |||

| 1 or less | 77 (45.8) | 37.9 (10.2) | 46.8 (8.5) | ||

| 2 or more | 91 (54.2) | 37.3 (11.1) | 48.5 (7.4) | ||

p < .05

p < .01

The association of early parental and peer attachment to global mental health in later adolescence and young adulthood

Initial latent growth models testing the utility of including both intercept and slope factors for constructs of primary interest suggested that the slope factors associated with peer attachment and global mental health had means and variances that did not differ significantly from zero. Therefore, the slope factors associated with these variables were removed from the model and a single latent factor representing the average score over the assessment period was calculated for each.

Table 3 contains the results of the final regression model. This model provided adequate fit to the data (χ2 (111) = 174.5; p < .01; CFI = 0.90; RMSEA = .05; 95%CIupper = .07; SRMR = .07). Higher levels of parental and peer attachment in early adolescence were associated with lower average GSI scores in later adolescence and young adulthood above and beyond parental and friend acceptance. Parental and friend acceptance were not significantly associated with GSI scores. Similarly, race, age, and gender were not significantly associated with GSI scores.

Table 3.

Early peer and parental attachment as predictors of global mental health in later adolescence.

| Predictor of GSI intercept | B | 95% CI | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental Attachment | |||

| Intercept | −0.01 | (−0.02, −0.003) | −.24** |

| Slope | −0.02 | (−0.07, 0.03) | −.11 |

| Peer Attachment | |||

| Intercept | −0.04 | (−0.06, −0.02) | −.44** |

| Parental Acceptance | 0.16 | (−0.09, 0.37) | .16 |

| Friend Acceptance | −0.11 | (−0.47, 0.34) | −.05 |

| Age | 0.003 | (−0.05, 0.05) | .01 |

| Gender (ref = Male) | 0.14 | (−0.02, 0.30) | .14 |

| Race (ref = White) | |||

| Black | −0.19 | (−0.40, 0.02) | −.19 |

| Latino/a | −0.04 | (−0.30, 0.22) | −.03 |

| Other | 0.004 | (−0.25, 0.26) | .003 |

p ≤ .05

p ≤ .01

Mediational pathways between early adolescent attachment and later adolescent and young adult relationship quality

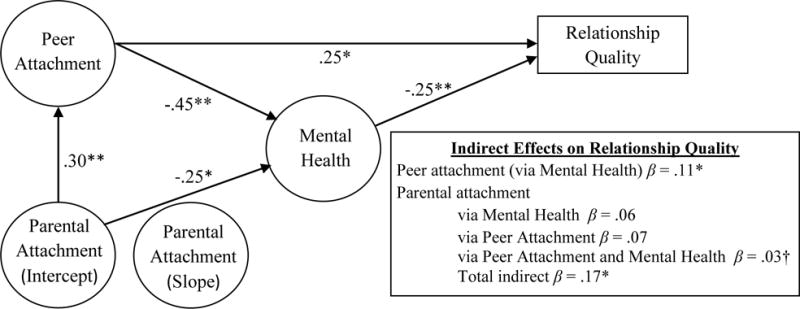

Two mediational pathways were hypothesized: (1) attachment to parents would be connected with relationship quality indirectly through peer attachment and (2) attachment to parents and peers would be indirectly related to relationship quality through mental health. In order to evaluate the significance of these mediational pathways, we calculated a structural equation model. Building on previous analyses, we initially included intercept and slope factors for parental attachment. Subsequently, regression parameters for the slope factor associated with parental attachment were constrained to be zero to facilitate model convergence. Also, consistent with previous analyses in which global mental health and peer attachment were found to be stable across time, both constructs were modeled using a single latent factor which represented the average score across assessment points. RAS scores were the final outcome in the model. Figure 1 illustrates relationships among primary variables of interest. Age, gender, race, friend acceptance, and parental acceptance were included in the model as correlates of mental health and relationship adjustment.

Figure 1. Indirect pathways from early attachment to later relationship quality in LGB adolescents.

NOTE: All coefficients represent standardized relationships among variables (β). Regression coefficients not pictured were constrained to be zero or not statistically significant. Overall model fit χ2 (132) = 230.8; p < .01; CFI = 0.87; RMSEA = .07; 95%CIupper = .08; SRMR = .08. R2relationship quality = .30 and R2mental health = .37.

* p ≤ .05; ** p ≤ .01.

Figure 1 depicts the standardized regression coefficients among the primary constructs of interest. The overall model provided an adequate fit to the data (χ2 (132) = 230.8; p < .01; CFI = 0.87; RMSEA = .07; 95%CIupper = .08; SRMR = .08) and accounted for a moderate amount of variance in mental health (R2 = .37) and relationship quality (R2 = .30). Consistent with the results of previous analyses, peer and parental attachment were significantly associated with global mental health. Also consistent with previous results, age, race, gender, family acceptance, and friend acceptance were not significantly associated with GSI scores.

In turn, higher GSI scores were associated with lower relationship adjustment scores. Neither peer nor parental attachment had a significant direct effect on RAS scores. With regard to covariates, RAS scores were not significantly associated with age, race, gender, or friend acceptance scores. There was a non-significant trend suggesting RAS scores were positively associated with parental acceptance (B = 0.37; 95%CI = −0.02, 0.75; β = .19; p =.065). Participants reported significantly lower RAS scores when they were reporting on a previous (rather than a current) relationship partner (B = −0.74; 95%CI = −1.16, −0.32; β = −.32; p < .01).

The indirect pathway from peer attachment to relationship quality through global mental health was significant and small in size (β = .11; 95%CI = .01, .21; p =.03). While the cumulative indirect pathway from parental attachment to relationship quality was statistically significant and small in size (β = .17; 95%CI = .05, .26; p < .01), none of the three possible individual indirect pathways were statistically significant at p < .05. The indirect pathway from parental attachment to relationship quality through peer attachment and global mental health was small (β = .03; 95%CI = −0.01, .07; p = .10), as were the individual indirect pathways through peer attachment (β = .07; 95%CI = −0.01, .15; p = .11) and global mental health (β = .06; 95%CI = −.02, .14; p = .15).

DISCUSSION

These results underscored the utility of attachment theory as a framework for thinking about data related to mental health and primary partner relationship quality in sexual minority adolescents and young adults. Both peer and parental attachment were associated with global mental health functioning. Previous research that has examined the connection between attachment and mental health has commonly looked at a general “style” of attachment which is assumed to operate across close relationship types (Shidlo, 1994; Simonelli et al., 2004; Steffens, 2005), but these data suggest that the security of attachments to peers and parents in earlier adolescence contributed uniquely to the prediction of global mental health in later adolescence and young adulthood among sexual minority youth. These findings are consistent with developmental conceptualizations of adolescence such as Erikson’s (1980), which emphasize expanding networks of relationships. The idea that attachment is shaped by parental interactions and these expectancies in turn influence behavior in a manner that shapes the quality of future relationships is also consistent with research conducted within transactional-ecological frameworks. This work posits that youth behavior is shaped by social context and that youths simultaneously exert an influence on social context through their interactions with it (Cicchetti, Toth, & Maughan, 2000; Henrich, Brookmeyer, Shrier, & Shahar, 2006; Sameroff, 1995). This kind of work reinforces the idea that peer relationships emerge as a significant factor in the psychological lives of adolescents; however, they also suggest that the importance of parental relationships is not completely eclipsed during this time period.

Results of mediational analyses supported the hypothesis that global mental health constituted a mechanism by which peer and parental attachment in early adolescence become linked with relationship quality in later adolescence. Patterns of significance indicated that peer attachments may be a more important factor in this association. The indirect pathway from peer attachment to relationship quality through mental health was significant, while the indirect pathway from parental attachment to relationship quality through mental health was not. This finding is consistent with the pattern of associations among peer attachment, parental attachment, and romantic relationship quality observed by Furman et al. (2002). Given that primary partner relationships likely bear more similarity to peer relationships than parental relationships for most youth, it makes some sense that patterns of peer attachment would be more closely linked to main partner relationship quality.

That said, these results indicate that parental relationships in early adolescence remain potentially relevant to relationship quality in later adolescence and emerging adulthood in two ways. First, trends indicated that parental acceptance may be directly associated with relationship quality scores even though parental attachment was not. Few previous studies have examined parental approval and aspects of parental attachment concurrently and those which have suggest several possible relationships among these constructs. Darby-Mullins and Murdock (2007) found that general family functioning and positive parental attitudes towards homosexuality both contributed to the prediction of emotional adjustment among LGB youth. In contrast, Elizur and Ziv (2001) reported that family acceptance mediated the relationship between family support and mental health outcomes in a sample of gay male adults. Divergence in findings may be due in part to differences in measurement. These studies employed various measures to assess constructs consistent with parent-adolescent attachment.

Second, these data indicate the possibility that parental attachment may retain a small indirect association with relationship adjustment through associations with peer attachment and mental health. While specific indirect pathways were all non-significant, the composite or total indirect effect of parental attachment on romantic relationship adjustment was statistically significant, suggesting a diffuse association in which stronger relationships with parents in early adolescence predict better romantic relationship adjustment in later adolescence and emerging adulthood. Broadly, this finding provides modest support for continued research focused on developmental trajectories of attachment across relationship types. This result, which implicates indirect pathways through both peer attachment and global mental health, represents a blending of the two hypothesized mediational pathways and suggests the possibility that both generalized relationship expectations and mental health functioning play a role in linking parental attachment in early adolescence with later relationship quality.

It is important to note that associations between attachment and mental health, as well as indirect effects on relationship quality, were tested controlling for parental and friend acceptance. In contrast to the findings of Darby-Mullins and Murdock (2007), acceptance did not contribute significantly to the prediction of global mental health. While these contrasts may be the result of sampling variability or measurement differences, another possible explanation for differences in findings is that the current study utilized a longitudinal design in which acceptance was measured at the 18 month follow-up and mental health was measured at 12-, 18-, 24-, and 42-month follow-ups, . It may be that acceptance has a stronger association with current mental health functioning.

Parental attachment security was associated with a later onset of dating. This finding is significant in light of recent evidence linking earlier age of dating debut to increasing sexual risk-taking during late adolescence and early adulthood (Moilanen, 2015). The finding is also consistent with previous research that has linked close connections with parents to later sexual debut among heterosexual samples or adolescent samples of diverse sexual orientation (Ackard et al., 2008; Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2012). One possible explanation for this finding is that high-quality relationships with parents delay engagement in the LGB community and thereby delay the onset of relationship engagement. This hypothesis is consistent with research conducted by Waldner and Magrader (1999), which found that adolescents who reported stronger connections to parents tended to wait longer to come out. The authors hypothesized that adolescents who perceive better relationships with parents may also perceive the cost of a potential breach in parental relationships associated with coming out as greater.

There are several reasons why peer attachment may be associated with relationship length. Research on social support and marginalization has indicated that individuals who experience acceptance and support for the intimate relationships in which they engage invest more and report stronger commitment to those relationships (Lehmiller & Agnew, 2006). Adolescents with secure attachments to peers may experience more social support and acceptance for their relationships from these peers. This in turn may enhance commitment and investment in a way that increases relationship duration for these youth. It is also possible that adolescents who are able to form secure attachments to peers are able to access social skills which serve them well in the selection of potential relationship partners and throughout the relationship process.

The results of this prospective study suggest that interventions which serve to enhance the security of parental and peer connections for sexual minority youth early in adolescence may be an important primary prevention strategy. These kinds of interventions may take a variety of forms. For example, LaSala (2000) suggested that family psychotherapy interventions around planned engagement and communication may help to improve outcomes for sexual minority clients during the coming out process. Alternatively, social skills training interventions, which have demonstrated effects of small to moderate in reducing emotional and behavioral disorders in youth (Cook et al., 2008; Maag, 2006) may be useful in the context of individual interventions delivered to sexual minority youth. They provide an approach to intervention which potentially cultivates relationship-enhancing skills. Another potential intervention option may include programs intended to enhance positive youth development by improving the safety and support experienced by sexual minority in schools (Macgillivray, 2014) and athletic activities (Griffin, Perrotti, Priest, & Muska, 2002).

These data underscore the inter-relatedness of individual and relationship health and suggest the utility of developing integrated interventions targeting mental health and sexual relationship health. While main partnerships have been associated with increased HIV sexual transmission risk (Goodreau et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2009) and more condomless sex, especially among younger MSM engaging in relationships (Newcomb, Ryan, Garofalo, & Mustanski, 2014), they have also been connected with improvements in psychological outcomes for sexual minority youth (Bauermeister et al., 2010; Russell & Consolacion, 2003). There are examples of existing interventions, developed within the framework of Motivational Interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2013), which have successfully achieved improvements in depression and self-esteem while reducing sexual risk-taking (Chen, Murphy, Naar-King, & Parsons, 2011; Naar-King, Parsons, Murphy, Kolmodin, & Harris, 2010). Interventions which facilitate the healthy negotiation of main partner relationships address a biopsychosocial factor which may have life-span implications.

Several limitations should be noted. First, we used a convenience sample that is not nationally representative, which may have introduced bias into the study. However, nationally representative surveys may not assess constructs that are nuanced to the experiences of sexual minority youth (e.g., acceptance of sexual orientation). Second, we did not make comparisons with heterosexual youth because our sample included only individuals who endorsed same-gender attractions. Future research should address whether findings are consistent with general adolescent samples by including a heterosexual comparison group or routinely assessing sexual orientation in large population-based health surveys. Relatedly, these analyses combined bisexual-identified participants with those who identified as gay or lesbian. The experience of being bisexual is unique from both the gay/lesbian experience (Bradford, 2004; Brown, 2002). While the limitations of model complexity prevented comparisons between sexual orientation groups, future studies should consider designs which would permit such comparisons. Third, analyses involved the global scores of the BSI. While sensitivity analyses found that results of subscales were generally consistent with findings based on the global scales, future studies should examine whether specific aspects of mental health are more strongly linked with attachment and/or relationship quality. Such studies may benefit from taking a multi-group approach, which would permit comparison of associations among constructs across sexual orientation groups. Finally, this study restricted analyses of relationship quality to youth who reported being in a relationship currently or in the 6 months preceding one of three follow-up periods. This was done to ensure that analyses reflected associations between attachment and relationship quality among youth who engaged in relationships. While the issue of main partner relationship quality per se is only relevant for youth who engage in these types of relationships, future research should examine associations between attachment to peers and parents and abstinence from main partner relationships. Such work may reveal potentially important connections with mental health as well as behaviors with casual sex partners.

CONCLUSIONS

These results provide evidence linking peer and parental attachment in adolescence with relationship milestones as well as mental health outcomes in later adolescence and young adulthood for LGB youth. Parental attachment security was associated with a delay in dating, while peer attachment security was associated with relationship length. Both peer and parental attachment were significantly associated with mental health outcomes. Furthermore, results indicated that global mental health may play a role in indirect pathways which link peer and parental attachment security with main partner relationship quality in a manner consistent with attachment theory.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a Grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R21MH095413; PI: Mustanski), an American Foundation for Suicide Prevention grant (PI: Mustanski), the William T. Grant Foundation Scholars Award (PI: Mustanski), and the David Bohnett Foundation (PI: Mustanski). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

References

- Ackard DM, Fedio G, Neumark-Sztainer D, Britt HR. Factors associated with disordered eating among sexually active adolescent males: Gender and number of sexual partners. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2008;70(2):232–238. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318164230c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MD. Attachments across the life span. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1985;61(9):792–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiocco R, Fontanesi L, Santamaria F, Ioverno S, Marasco B, Baumgartner E, Laghi F. Negative parental responses to coming out and family functioning in a sample of lesbian and gay young adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9954-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Johns MM, Sandfort TGM, Eisenberg A, Grossman AH, D’Augelli AR. Relationship trajectories and psychological well-being among sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(10):1148–1163. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9557-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Benner A, Coleman E. Gay and bisexual identity development among female-to-male transsexuals in North America: Emergence of a transgender sexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:688–701. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9489-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouris A, Guilamo-Ramos V, Pickard A, Shiu C, Loosier PS, Dittus P, Waldmiller JM. A systematic review of parental influences on the health and well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Time for a new public health research and practice agenda. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31:273–309. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. The making and breaking of affectional bonds. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1977;130(3):201–210. doi: 10.1192/bjp.130.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford The bisexual experience: Living in a dichotomous culture. Journal of Bisexuality. 2004;4:7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brown T. A proposed model of bisexual identitiy development that elaborates on experiential differences of women and men. Journal of Bisexuality. 2002;2:67–91. [Google Scholar]

- Butzer B, Campbell L. Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships. 2008;15(1):141–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00189.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Murphy DA, Naar-King S, Parsons JT. A clinic-based motivational intervention improves condom use among subgroups of youth living with HIV. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;49(2):193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.11.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Maughan A. An ecological-transactional model of child maltreatment. In: Lewis M, Miller SM, editors. Handbook of developmental psychopathology. New York: Plenum Publishers; 2000. pp. 689–722. [Google Scholar]

- Collins NL, Read SJ. Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58(4):644–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook CR, Gresham FM, Kern L, Barreras RB, Thorton S, Crews SD. Social skills training for secondary students with emotional and/or behavioral disorders: A review and analysis of the meta-analytic literature. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2008;16(3):131–144. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Developmental and contextual factors and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. In: Omoto AM, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual orientation and mental health: Examining identity and development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth and their families: Disclosure of sexual orientation and its consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(3):361–371. doi: 10.1037/h0080345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby-Mullins P, Murdock TB. The influence of family environmental factors on self-acceptance and emotional adjustment among gay, lesbian and bisexual adolescents. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2007;3(1):75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich U, De Wit J, Stroebe W. Relationship characteristics and risk of HIV infection: Rusbult’s investment model and sexual risk behavior of gay men in steady relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2006;36(1):22–40. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00002.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. BSI 18: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Devor AH. Witnessing and mirroring: A fourteen stage model of transsexual identity formation. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy. 2004;8(1/2):41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Elizur Y, Ziv M. Family support and acceptance, gay identity formation, and psychological adjustment: A path model. Family Process. 2001;40:125–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Stein TS, Harter KSM, Allison A, Nye CL. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: Separation-individual, parental attitudes, identity consolidation, and well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1999;28(6):719–739. [Google Scholar]

- Ford CA, Pence BW, Miller WC, Resnick MD, Bearinger LH, Pettineell S, Cohen M. Predicting adolescents’ longitudinal risk for sexually transmitted infection: Results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159(7):657–664. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH. Internalized Homophobia and Relationship Quality among Lesbians, Gay Men, and Bisexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56(1):97–109. doi: 10.1037/a0012844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA, Shaffer L, Bouchey HA. Adolescents’ working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development. 2002;73(1):241–255. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, Harper GW. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Explorign the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006a;38:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodreau SM, Carnegie NB, Vittinghoff E, Lama JR, Sanchez J, Grinsztejn B, Buchbinder SP. What drives the U.S. and Peruvian HIV epidemics in men who have sex with men (MSM)? PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e50522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P, Perrotti J, Priest L, Muska M. It takes a team! Making sports safe for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender athletes and coaches. An educational kit for athletes, coaches, and athletic directors. New York: Womens’ Sports Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Lee JE, McCarthy K, Michael SL, Pitt-Barnes S, Dittus P. Paternal influences on adolescent sexual risk behaviors: A structured literature review. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1313–e1325. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(5):707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44:174–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick SS. A generic measure of relationship satisfaction. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1988;50:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich CC, Brookmeyer KA, Shrier LA, Shahar G. Supportive relationships and sexual risk behavior in adolescence: An ecological-transactional approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(3):286–297. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzen DW, Kenny ME, Mahalik JR. Contributions of parental attachment to gay or lesbian disclosure to parents and dysfunctional congitive processes. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1995;42(3):350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Keelan JPR, Dion KK, Dion KL. Attachment style and relationship satisfaction: Test of a self-disclosure explanation. Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science. 1998;30(1):24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Palmer NA, Boesen MJ. The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network (GLSEN); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kuttler AF, La Greca AM. Linkages among adolescent girls’ romantic relationships, best friendships, and peer networks. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27(4):395–414. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaSala MC. Lesbians, gay men, and their parents: Family therapy for the coming-out crisis. Family Process. 2000;39(1):67–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmiller JJ, Agnew CR. Marginalized relationships: The impact of social disapproval on romantic relationship commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2006;32(1):40–51. doi: 10.1177/0146167205278710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, Mustanski B. Suicidal ideation and self-harm in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42(3):221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maag JW. Social skills training for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: A review of reviews. Behavioral Disorders. 2006;32(1):5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Macgillivray IK. Gay-straight alliances: A handbook for students, educators, and parents. New York: Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta N, Cowan PA, Cowan CP. Working models of attachment to parents and partners: Implications for emotional behavior between partners. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(6):895–899. doi: 10.1037/a0016479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 3rd. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JW, Harvey SM, Champeau D, Seal DW. Relationship factors associated with HIV risk among a sample of gay male couples. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(2):404–411. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9976-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen KL. Predictors of latent growth in sexual risk taking in late adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Sex Research. 2013 doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.826167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SW, Stevens PE. Transgender identity development as represented by a group of female-to-male transgendered adults. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2008;29(6):585–599. doi: 10.1080/01612840802048782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Parsons JT, Murphy DA, Kolmodin K, Harris DR. A multisite randomized trial of a motivational intervention targeting multiple risks in youth living with HIV: Initial effects on motivation, self-efficacy, and depression. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(5):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. The effects of sexual partnership and relationship characteristics on three sexual risk variables in young men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43:61–72. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0207-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis MD, Riggle ED, Rostosky SS. Impact of mental health on perceptions of relationship satisfaction and quality among female same-sex couples. Journal of Lesbian Studies. 2006;10(1–2):267–283. doi: 10.1300/J155v10n01_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Goldfried MR, Ramrattan ME. Extension of the rejection sensitivity construct to the interpersonal functioning of gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(2):306–317. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja SN, McGee R, Stanton WR. Perceived attachments to parents and peers and psychological well-being in adolescenc. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1992;21:471–485. doi: 10.1007/BF01537898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Critical role of disclosure reactions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(1):175–184. doi: 10.1037/a0014284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Consolacion TB. Adolescent romance and emotional health in the United States: Beyond binaries. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(4):499–508. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner DM, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ. General systems theories and developmental psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Manual of developmental psychopathology: Theory and methods. Vol. 1. New York: Wiley; 1995. pp. 659–695. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Coming out to parents and self-esteem among gay and lesbian youths. Journal of Homosexuality. 1989;18(1–2):1–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v18n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifer R, Schiller M, Sameroff A, Resnick S, Riordan K. Attachment, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament during the first year of life. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(1):12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shidlo A. Internalized homophobia: Conceptual and empirical issues in measurement. In: Green B, Herek GM, editors. Lesbian and Gay Psychology: Theory Research and Clinical Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. pp. 176–205. [Google Scholar]

- Sieving RE, Eisenberg ME, Pettingell S, Skay C. Friends’ influence on adolescents’ first sexual intercourse. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(1):13–19. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.013.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonelli L, Ray W, Pincus AL. Attachment models and their relationships with anxiety, worry and depression. Counseling and Clinical Psychology Journal. 2004;1:107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens MC. Implicit and explicit attitudes towards lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality. 2005;49(2):39–66. doi: 10.1300/J082v49n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Hamouda O, Delpech V, Geduld JE, Prejean J, Semaille C, Annecy MSM Epidemiology Study Group Reemergence of the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men in North America, Western Europe, and Australia, 1996–2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(6):423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonry M, Ohlin LE, Farrington DP. Human development and criminal behavior: New ways of advancing knowledge. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau. Facts for Features: Unmarried and Single Americans Week Sept. 2014 Dec 8;:21–27. 2014. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2014/cb14-ff21.html.

- Waldner LK, Magrader B. Coming out to parents: Perceptions of family relations, perceived resources and identity expression as predictors of identity disclosure for gay and lesbian adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;37(2):83–99. doi: 10.1300/J082v37n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Jacobsen P, Curbow B, Piantadosi S, Hooker C, Derogatis L. A new psychosocial screening instrument for use with cancer patients. Psychosomatics. 2001;42(3):241–246. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.42.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]