Abstract

Polygodial, a terpenenoid dialdehyde isolated from Polygonum hydropiper L., is a known TRPV1 agonist. In this investigation a series of polygodial analogues were prepared and investigated for TRPV1 agonistic and anticancer activities. These experiments led to the identification of 9-epipolygodial, possessing antiproliferative potency significantly exceeding that of polygodial. Epipolygodial maintained potency against apoptosis-resistant cancer cells as well as those displaying the MDR phenotype. In addition, a chemical feasibility for the previously proposed mechanism of action of polygodial, involving the Paal-Knorr pyrrole formation with a lysine residue on the target protein, was demonstrated through the synthesis of a stable polygodial pyrrole derivative. These studies reveal rich chemical and biological properties associated with polygodial and its direct derivatives. They should inspire further work in this area aimed at the development of new pharmacological agents or exploration of novel mechanisms of covalent modification of biological molecules with natural products.

Keywords: Ion channel, capsaicin, vanilloid, resiniferatoxin, capsazepine

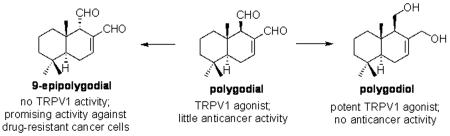

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

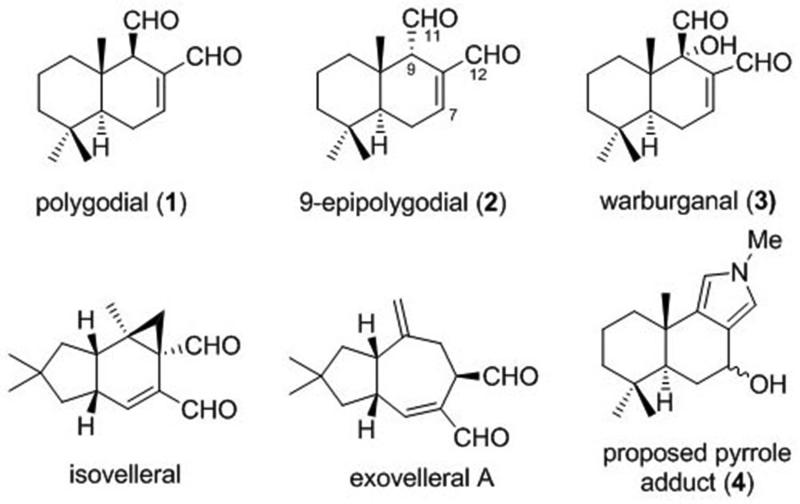

Polygodial (1, Figure 1) is a bicyclic sesquiterpene, first isolated as a pungent component of the sprout of Polygonum hydropiper L. (Polygonaceae), a plant once used as a pepper substitute in Europe and still a popular condiment for sashimi in Japan.1 It is a member of a family of over 80 terpenoids containing an α,β-unsaturated 1,4-dialdehyde functionality that have been isolated from a variety of natural sources including terrestrial plants, fungi, algae, liverworts, arthropods, sponges and molluscs.2 Some additional members of this family are shown in Figure 1 and they are believed to protect the producing organisms from predators.2,3 Indeed, a significant amount of early biological investigations involving these dialdehydes focused on their hot taste to the human tongue and antifeedant activities, both of which appeared to depend on the configuration of the aldehyde group at C9. Specifically, these studies found that polygodial (1) possesses potent antifeedant activity against African armyworms4 and fish5 and tastes hot to the human tongue.6 In contrast, 9-epipolygodial (2) is tasteless to humans and devoid of antifeedant activity toward insects4 or fish.5

Figure 1.

Structures of selected α,β-unsaturated 1,4-dialdehyde terpenoids and a proposed pyrrole adduct of 1 with methylamine (4)

The antifeedant effects of polygodial and related bicyclic sesquiterpenes with C9-β-configuration have been theorized to arise from their covalent interaction with receptors involved in taste perception. Electrophysiological studies revealed that when the maxillary palp (equivalent to taste buds) of the Spodoptera exempta larva is repeatedly brought in contact with filter paper infused with warburganal (3), a related dialdehyde shown in Figure 1, the taste sense is irreversibly blocked. As a consequence of this irreversible blockage, an armyworm, placed on a warburganal-treated maize leaf and subsequently transferred to an untreated leaf, starves to death.7

The formation of covalent adducts of polygodial with biological molecules involved in taste perception has been proposed to occur through either a reaction with –SH6 or NH28 groups. Furthermore, based on the NMR spectroscopic monitoring of the reaction of 1 with methyl amine in a phosphate buffer at pH 9 formation of pyrrole adduct 4 (Figure 1) was proposed.8-10 However, to our knowledge, no pyrrole adduct from the reaction of polygodial with primary amines has ever been isolated and characterized and, thus, the feasibility of such processes in chemical model systems remained to be demonstrated.

Later studies revealed anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory activities11 associated with polygodial and, in addition, the discovery of its antifungal properties has led to its therapeutic use to control localized candidiasis (Kolorex Capsules).12 Notably, except for mild stomach discomfort and dizziness, polygodial is well-tolerated by the majority of patients.13 However, it was the discovery of polygodial’s vanilloid activity and its potential use as an anti-nociceptive that has generated recent enthusiasm in the scientific literature.13-18 In a manner similar to capsaicin, a pungent component of hot chili pepper used as a spice in the culinary traditions of many countries, polygodial was found to inhibit the pain response invoked by formalin injection and block acetic acid-induced writhing in mice.19 To produce their nociceptive activities, polygodial, capsaicin and the other vanilloids are believed to target a transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptor (TRPV1), a temperature sensitive ion channel with preference for Ca2+ ions.20-24 Further research has shown that in addition to the expression in sensory neurons and involvement in different modalities of pain, TRPV1 is also upregulated in various human cancer cells25-27 and its activation in human glioma cells leads to ER stress followed by cell death.28 TRPV1 thus appears to be a promising target for cancer drug development and many reports investigating TRPV1 ligands, such as TRPV1 agonists capsaicin29-31 and resiniferatoxin27,32 as well as TRPV1 antagonists capsazepine29,30 and SB366791,29 as potential anticancer agents have appeared in the literature. However, mechanistic studies muddy the waters by questioning whether vanilloids’ anticancer effects are TRPV1-mediated and have revealed that TRPV1 antagonists generally do not prevent vanilloid agonist-induced cell death.27,29-32 Despite several reports of cytotoxic activity associated with polygodial,33-39 to our knowledge this TRPV1 agonist, or related bicyclic sesquiterpene dialdehydes, have not been investigated as potential anticancer agents. The current report details our synthetic study of polygodial (1), the generation of a series of its analogues and the evaluation of the synthesized compounds for TRPV1 and anticancer activities. This work has led to the discovery of 9-epipolygodial (2) as a promising agent against drug-resistant cancer and polygo-11,12-diol as a non-cytotoxic TRPV1 agonist. In addition, our study concludes that the anticancer effects in this series of compounds are also non-TRPV1-mediated paralleling the previous findings with other TRPV1 agonists.

Chemistry

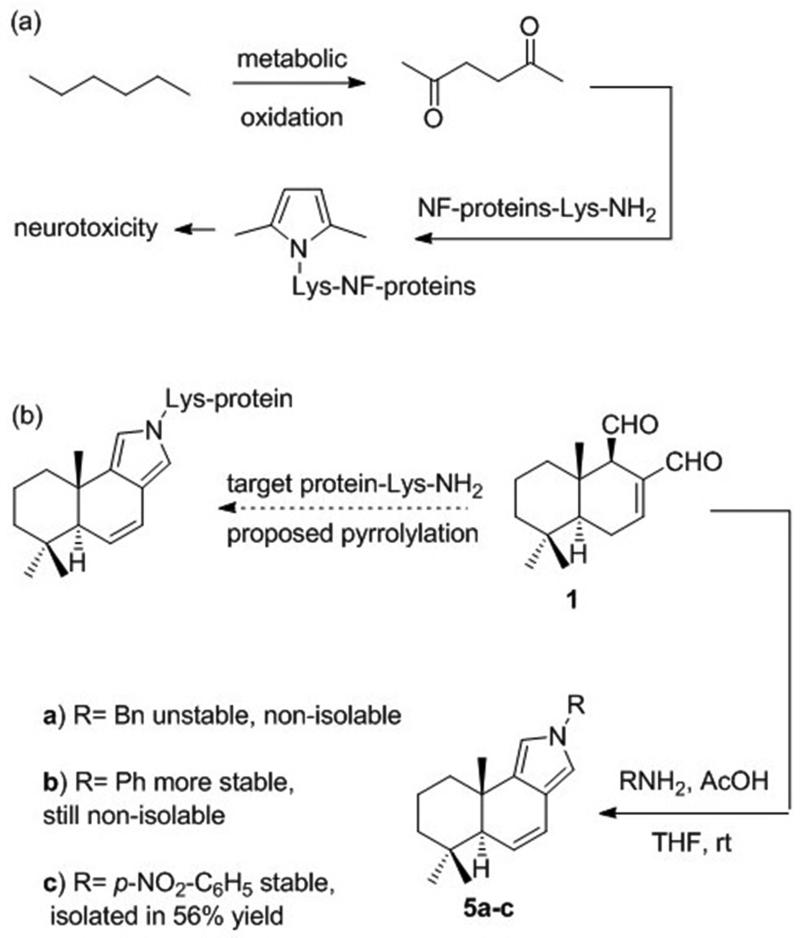

The Paal-Knorr condensation of primary amines with 1,4-dicarbonyl compounds is a well-studied classical pyrrole synthesis.40 The biological significance of this reaction, however, appears to be severely under-appreciated despite the wide occurrence of the 1,4-dicarbonyl functionality in natural products that could potentially react with lysine residues on proteins. The most well studied example of the biological relevance of the Paal-Knorr reaction is its involvement in n-hexane-induced axonal atrophy in the central nervous system. It has been demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo that 2,5-hexanedione, a neurotoxic n-hexane metabolite, undergoes a selective Paal-Knorr condensation with lysine residues of axonal cytoskeleton proteins, forming 2,5-dimethylpyrrole adducts within specific regions of neurofilaments (Scheme 1a).41 To our knowledge, the only other demonstrated example of lysine pyrrolylation with a 1,4-dicarbonyl compound involves the lysozyme modification with spongian diterpenes, which is responsible for Golgi-modifying properties of these marine natural products.42

Scheme 1.

(a) Paal-Knorr pyrrole formation implicated in the neurotoxicity of hexane and (b) proposed lysine pyrrolylation by 1 and chemical demonstration of its feasibility

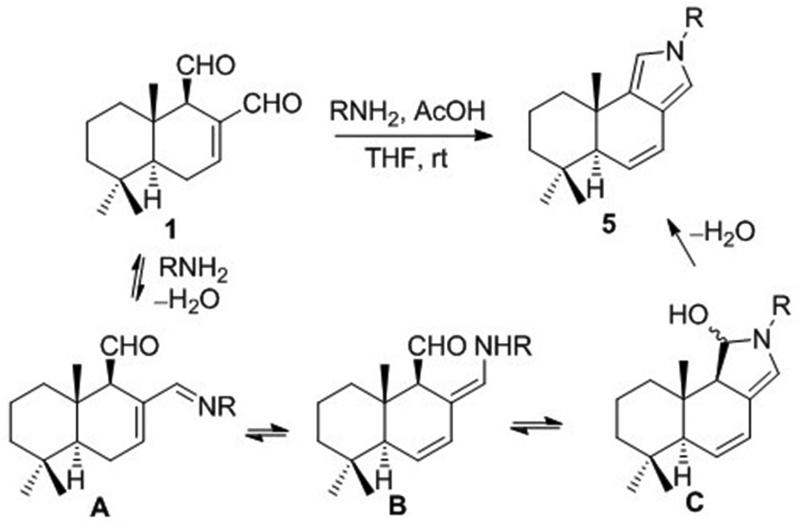

To support the intriguing proposal that a modified Paal-Knorr condensation with a target lysine residue is responsible for the covalent interaction of polygodial with biological macromolecules as described in the Introduction, 1 was reacted with benzyl amine under mild acid catalysis (Scheme 1b). Although TLC and MS monitoring of the reaction mixture indicated the possible formation of pyrrole 5a (R = Bn), attempts to isolate it were unsuccessful, likely due to susceptibility of the vinyl pyrrole functionality to oxidation. This problem was solved by using aniline and p-nitroaniline to make the resulting pyrrole ring system electron-deficient and in the latter case pyrrole 5c (R = p-NO2-C6H5) was successfully isolated as a stable polygodial derivative. Scheme 2 delineates a possible mechanism for this modified Paal-Knorr condensation, which likely involves attack by the primary amine at the more reactive C12-aldehyde to give imine A, which tautomerizes to dienamine B eventually leading to the irreversible formation of pyrrole 5.

Scheme 2.

Chemical mechanism of the modified Paal-Knorr pyrrole condensation of 1 with primary amines

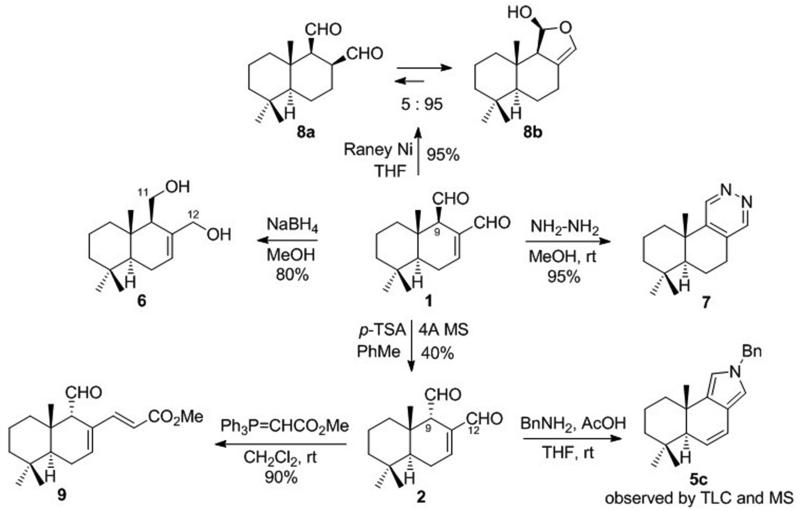

Chemical derivatization of 1 included two previously described orthogonal reduction processes,43,44 one with NaBH4 to give polygo-C11,C12-diol 6, the other with RaNi to yield dihydro analogue 8, which existed as an equilibrating mixture of dialdehyde 8a and lactol 8b (Scheme 3). Next, it was found that the reaction with hydrazine produced pyridazine 7, while acid-catalyzed enolization/epimerization gave the C9-epimeric mixture of 1 and 2, from which 9-epipolygodial (2) was isolated in 40% yield. The C12-aldehyde group in 2 proved to be more reactive and was selectively converted to unsaturated ester in 9 upon a reaction with methyl triphenylphosphoranilydeneacetate. Finally, compound 2 was found to undergo the Paal-Knorr pyrrole formation in a manner similar to epimeric 1 (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

General derivatization of polygodial

Previous literature45 also suggested that the reactive aldehyde groups in polygodial (1) could be masked by the formation of cyclic bis-acetals (Scheme 4). Indeed, when 1 was treated with various alcohols in the presence of p-TSA, acetals 10-16 were produced as mixtures of two diastereomers with the configurations of the C11 and C12 positions as shown for a and b (Scheme 4). The idea behind the synthesis of a series of such analogues was to facilitate the selective pyrrole formation at polygodial’s target site. Although aldehyde-containing compounds do not present any particular metabolic concerns and are often present in clinical drugs (e.g. orally bioavailable male contraceptive gossypol, a dialdehyde also currently studied in cancer clinical trials46), moderating the reactivity of the dialdehyde functionality could be an attractive tool to improve the pharmacokinetic properties of such compounds. Indeed, with the right reactivity-stability balance of such cyclic bis-acetals, the pyrrole formation at the target protein’s active site would still be possible, but the wasteful non-specific reactions with endogenous free amines and accessible lysine residues on abundant proteins could be minimized.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of cyclic bis-acetals 10a,b-16a,b

Antiproliferative Activities

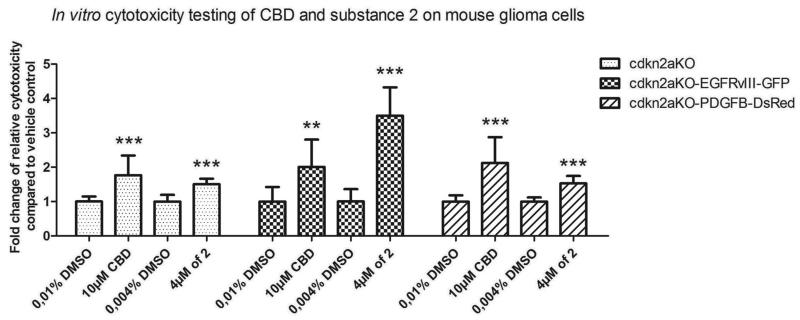

The synthesized compounds were evaluated for in vitro growth inhibition using the MTT colorimetric assay against a panel of five cancer cell lines including apoptosis-resistant human glioblastoma (GBM) U373,47 human A549 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)48 and human SKMEL-28 melanoma,49 as well as apoptosis-sensitive human Hs683 anaplastic oligodendroglioma47 and human MCF-7 breast cancer.50 Analysis of these data reveals that polygodial (1) and most of the synthesized derivatives displayed little activity in this cancer cell line panel, with the exception of 9-epipolygodial (2). Compound 2 was at least 20 times as potent as polygodial (1) and did not appear to discriminate between apoptosis resistant and apoptosis-sensitive cells by displaying comparable single digit micromolar potencies in both cell types (Table 1). It should be noted that the potent activity of compound 2 was initially surprising given its recent evaluation by Montenegro against a panel of cancer cell lines, who reported no activity associated with this compound up to 200 μM.39 However, we retested this compound for using multiple repeats with different assays on a large number of different cells lines as can be seen below and thus are confident in our conclusions.

Table 1.

In vitro growth inhibitory effects of polygodial derivatives

| compound | GI50 in vitro values (μM)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| A549 | SKMEL-28 | MCF-7 | U373 | Hs683 | Mean + SEM | |

| 1 | 84 ± 9 | 65 ± 3 | 75 ± 2 | 99 ± 6 | 95 ± 1 | 84 ± 6 |

| 2 | 6 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 0.1 | 5± 0.2 | 6 ± 0.2 | 4 ± 1 |

| 5 | 98 ± 2 | > 100 | 66 ± 3 | > 100 | 82 ± 2 | > 89 ± 7 |

| 6 | > 100 | > 100 | 93 ± 3 | > 100 | > 100 | > 99 ± 1 |

| 7 | > 100 | > 100 | 72 ± 3 | > 100 | 93 ± 2 | > 93 ± 5 |

| 8 | 35 ± 1 | 72 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 86 ± 3 | 33 ± 1 | 50 ± 12 |

| 9 | 29 ± 1 | 70 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 | 33 ± 0.5 | 40 ± 8 |

| 10a | 96 ± 3 | 77 ± 2 | 77 ± 2 | 84 ± 2 | 88 ± 3 | 84 ± 4 |

| 10b | 64 ± 2 | 30 ± 1 | 38 ± 3 | 29 ± 1 | 56 ± 2 | 43 ± 7 |

| 11a & b | 28 ± 1 | 56 ± 2 | 39 ± 2 | 42 ± 1 | 30 ± 0.3 | 39 ± 5 |

| 12a | > 100 | > 100 | 81 ± 3 | > 100 | 83 ± 2 | > 93 ± 4 |

| 13a | > 100 | > 100 | 83 ± 3 | > 100 | 78 ± 4 | > 92 ± 5 |

| 13b | > 100 | > 100 | 66 ± 3 | > 100 | 97 ± 4 | > 93 ± 7 |

| 14b | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 15a & b | 69 ± 4 | 11 ± 1 | 33 ± 1 | 22 ± 3 | 35 ± 2 | 34 ± 10 |

| 16a & b | 41 ± 1 | 49 ± 3 | 34 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 28 ± 1 | 38 ± 3 |

Average ± SEM concentration required to reduce the viability of cells by 50% after a 72 h treatment relative to a control, each experiment performed once in sextuplicates, as determined by MTT assay.

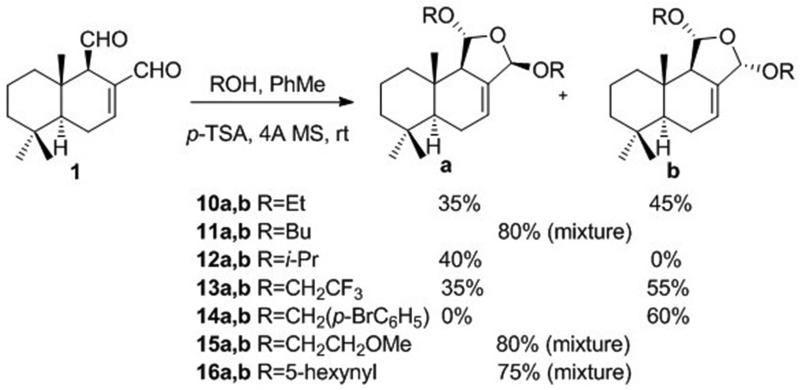

Our previous experience of working with cells intrinsically resistant to various proapoptotic stimuli shows that common chemotherapeutic agents that work through the induction of apoptosis rapidly eliminate a certain population of sensitive cells generating low GI50 values. However, these high potencies can be misleading as the remaining cells can resist the effects of chemotherapeutic agents even at concentrations 100- or 1000-fold of their GI50s.47,51 It was thus instructive to learn that compound 2 eliminates all cells in the cultures and generates no resistant populations (close to 0% cell viability) at concentrations just slightly exceeding its GI50 values (Figure 2A). The contrasting effects on cell viability between 2 and chemotherapeutic agents paclitaxel and podophyllotoxin are shown in Figures 2B and 2C. As can be seen, paclitaxel and podophyllotoxin have no effect on proliferation of ca. 50% of cells in U87 GBM and A549 NSCLC cell cultures at concentrations up to 50 μM, whereas 2 exhibited potent growth inhibitory properties against most of the cells in these cultures and, with increasing concentration, rapidly reached the antiproliferative levels of a non-discriminate cytotoxic agent phenyl arsine oxide (PAO). Compound 2 demonstrated a similar behaviour in docetaxel-resistant SCC4 and cisplatin-resistant SCC25 human oral cancer cell lines, as well as the docetaxel-resistant PC-3 human prostate cells (data not shown).

Figure 2.

(A) Elimination of all cells in all 5 cultures tested with analogue 2 and contrasting effects on viability of all cells between 2 and standard chemotherapeutic agents paclitaxel and podophyllotoxin in (B) U87 GBM and (C) A549 NSCLC cell cultures

In contrast to the intrinsic resistance described above, tumors often initially respond to chemotherapy, but eventually become refractory to the continuing treatment. In such an instance of acquired resistance cancer cells usually develop a multi-drug resistant phenotype (MDR) affecting a broad spectrum of structurally and mechanistically diverse antitumor agents.52,53 The phenomenon of MDR has plagued, for example, conventional therapy with vinca alkaloids53 or taxanes54 and, thus, it was of interest to evaluate 2 against MDR cells. The MDR uterine sarcoma cell line MES-SA/Dx5 is resistant to multiple functionally and structurally unrelated molecules55 and it was established by growing the parent uterine sarcoma MES-SA in the presence of increasing concentrations of doxorubicin. Paclitaxel (Table 2) and vinblastine lost their potency by a thousand fold when tested for antiproliferative activity against the MDR cell line as compared with the parent line. In contrast, there was little variation in the sensitivities of the two cell lines towards 2 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antiproliferative effects of 2 against MDR cells

| GI50 in vitro values (μM)a | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| MES-SA | MES-SA/D×5 | |

|

|

||

| Paclitaxel | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 9.8 ± 0.3 |

| Vinblastine | 0.006 ± 1 | 5.0 ± 1.4 |

| 2 | 10.7 ± 0.7 | 6.8 ± 0.4 |

Concentration required to reduce the viability of cells by 50% after a 48 h treatment with the indicated compounds relative to a DMSO control ± SD from two independent experiments, each performed in 4 replicates, as determined by the MTT assay.

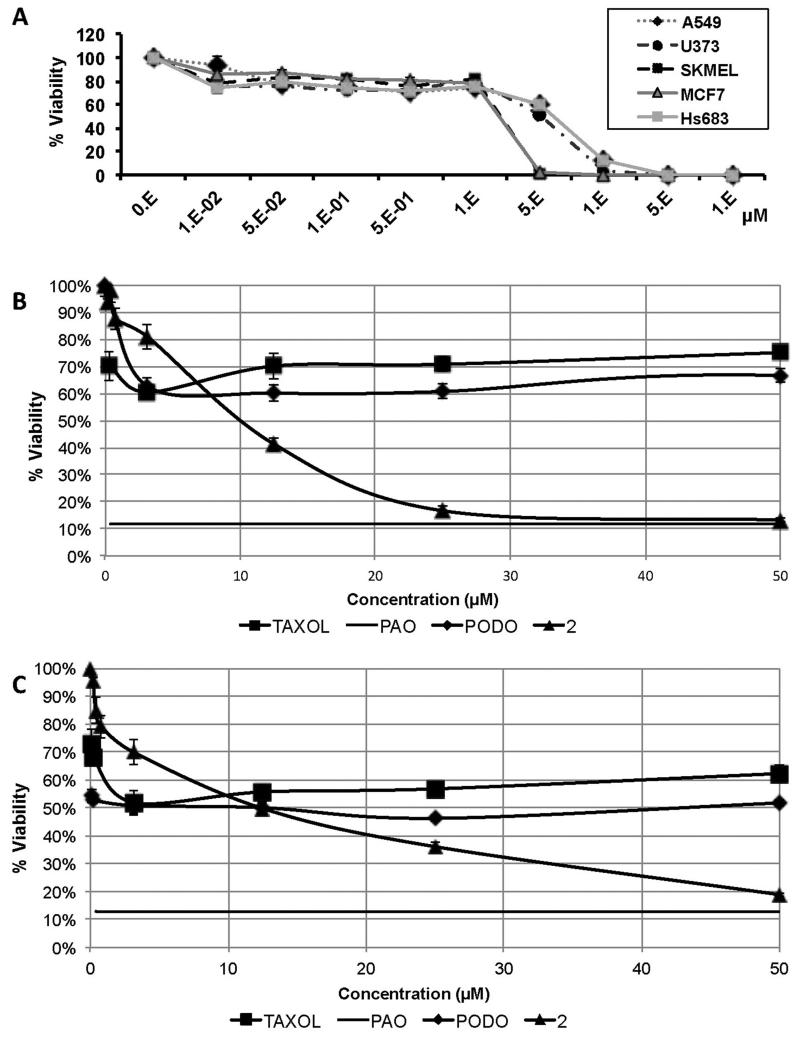

The ability of 2 to overcome drug resistance was further evaluated using glioma cell cultures maintained under neurosphere conditions known to promote the growth of stem-like cells from human glioma tissue. Neurospheres have been shown to recapitulate human gliomas on both histological and genetic levels more faithfully than serum cultured glioma cell lines when injected into the brains of mice56-59 and they are generally resistant to radiation and chemotherapy.60-63 The small neurosphere cell culture panel chosen for this study included cells carrying a tumor suppressor cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (cdkn2a) deletion64 as well as epidermal growth factor receptor variant III (EGFRvIII)65 and platelet-derived growth factor subunit (PDGFB)66 amplifications, representing frequent mutations in high-grade astrocytic tumors. The data shown in Figure 3 indicate that compound 2 used at 4 μM (average GI50 in Table 1) is as toxic to these cells as cannabidiol (CBD) at 10 μM, an orphan drug advanced to phase II clinical trials for the treatment of GBM.

Figure 3.

Activity of 2 against neurosphere glioma cell cultures with clinically relevant mutations. Transgenic mouse gliomas of defined molecular subtypes were generated by forced expression of EGFRvIII (classical GBM subtype) or PDGFB (proneural GBM subtype) in cdkn2a-deficient subventricular neural precursors (NPC). These 2 different mouse gliomas and cdkn2a-deficient NPC were treated for 24 hours either with 10 μM CBD versus a corresponding vehicle-control (containing 0.01% DMSO) or 4 μM of 2 versus vehicle control (0,004% DMSO). Cytotoxicity was measured 24 h after incubation and base-line cytotoxicity levels in the controls were arbitrarily defined as 1. Read-outs from treated cells were normalized to their respective vehicle controls and the fold change of relative cytotoxicity was calculated. Each bar represents the mean ± SD; satistical significance, as determined by unpaired t-tests, is indicated: *** represents p < 0,001; ** p < 0,005).

Vanilloid Activities

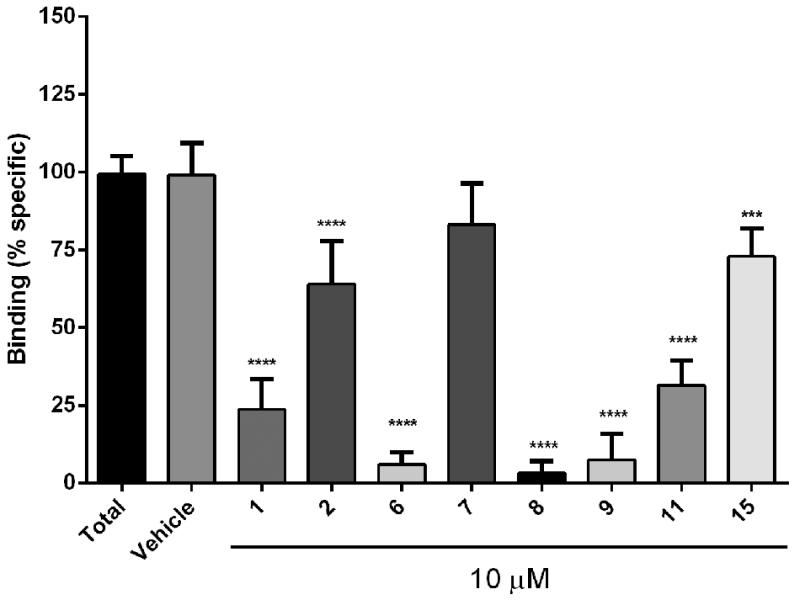

To evaluate the affinities of the synthesized polygodial derivatives to the vanilloid site of TRPV1, the compounds were assessed for their inhibition of specific binding of [3H]-resiniferatoxin (RTX) in rat spinal cord membranes.16 The results (Figure 4) demonstrate that at the concentration of 10 μM, polygodial (1) displayed 76% inhibition, whereas polygo-11,12-diol (6), 7,8-dihydropolygodial (8) and unsaturated ester 9 turned out more potent in this assay and showed 94%, 97% and 93% inhibition respectively. The lack of activity of 9-epipolygodial (2), the most promising analogue active against drug-resistant cancer, was somewhat surprising. However, this result is consistent with earlier findings that this natural product is tasteless to humans and devoid of antifeedant activity,3,4 strongly suggesting that the biological effects of 2 are not TRPV1-mediated.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of selected polygodial analogues in a [3H]-RTX TRPV1 displacement assay. Effect of a single concentration (10 μM) of the selected analogues in the specific binding of [3H]-RTX to the vanilloid site of TRPV1 receptor from rats spinal cord membranes. Results are expressed as mean ± S.E.M from 3 independent experiments, analyzed by one way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test (***p<0.05 and ****p<0.001).

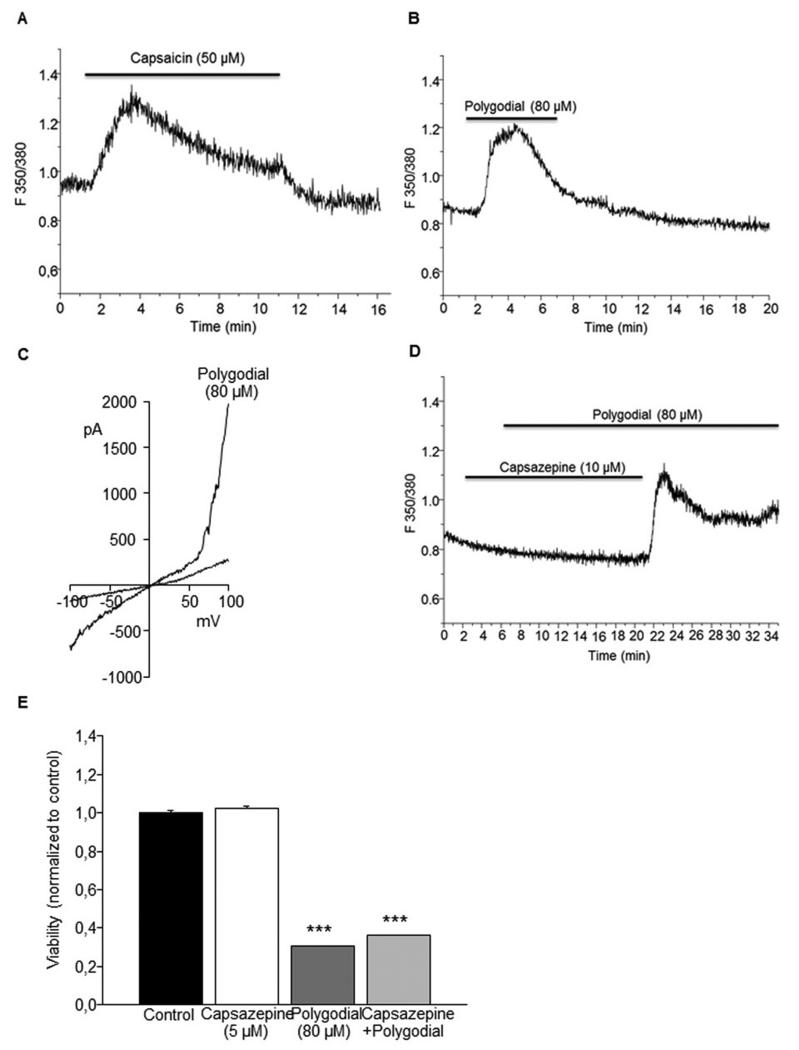

In a complementary assessment of TRPV1 activities, measurements of Ca2+ entry into MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells abundantly expressing TRPV1 receptors67 were performed (Figure 5). In a manner similar to capsaicin (Figure 5A), polygodial (1) at its average GI50 concentration of 80 μM (from Table 1) caused [Ca2+]i increase in these assays (Figure 5B). This activity was completely inhibited with the selective TRPV1 antagonist capsazepine (Figure 5D). Furthermore, TRPV1-like currents were recorded using whole-cell patch-clamp in MDA-MB-231 following external perfusion with polygodial at 80 μM (Figure 5C). Taken together, these results showed that polygodial activated TRPV1 in plasma membrane of MDA-MB-231. Moreover, an MTT assay using a 24 h non-toxic treatment with capsazepine (5 μM) was performed to inhibit the activity of TRPV1 in the presence of polygodial (80 μM). The results indicated that capsazepine alone did not affect the viability in MDA-MB-231, whereas polygodial strongly inhibited MDA-MB-231 viability. Interestingly, capsazepine did not counterbalance the effect of polygodial suggesting that the anticancer effects of polygodial are also independent of TRPV1 activity (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

Effect of polygodial on TRPV1 activity in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. (A) Effect of capsaicin on MDA-MB-231 [Ca2+]i. (B) Effect of polygodial on MDA-MB-231 [Ca2+]i. (C) TRPV1-like current activation. (D) Effect of capsazepine on polygodial-mediated [Ca2+]i response. (E) Effect of co-treatment with polygodial and capsazepine on the 24 h cell viability (*** p<0.001; Two-way ANOVA following by Holm-Sidak tests).

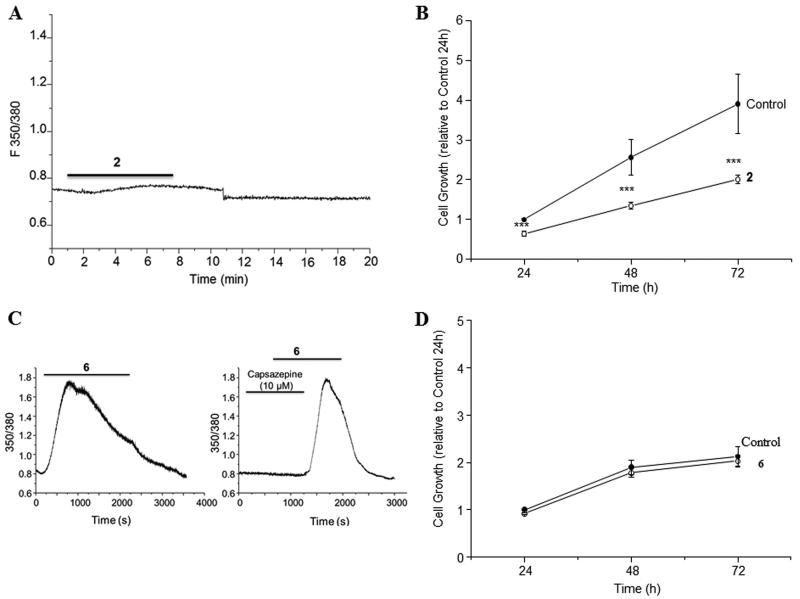

The results of the measurements of [Ca2+]i into MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells induced by 9-epipolygodial (2) and polygo-11,12-diol (6) were also consistent with the findings in the above-described [3H]-RTX displacement assay. Compound 2 had no effect on [Ca2+]i (Figure 6A), while killing approximately half the cells at the same concentration of 4 μM (Figure 6B), clearly through a TRPV1-independent mechanism. In contrast, compound 6, while lacking any toxicity (Figure 6D), led to a rapid increase of [Ca2+]i (Figure 6C) in a TRPV1-dependent manner as confirmed by the inhibition of this process with a TRPV1-specific antagonist capsazepine (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

(A) Lack of an effect of 9-epipolygodial (2) on [Ca2+]i despite (B) a pronounced effect of cell viability of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells at 4 μM. (C) Effect of polygodiol 6 on [Ca2+]i into TRPV1-expressing MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, which is blocked with capsazepine. (E) Lack of an effect of polygodiol 6 on cell viability at these concentrations.

Previous studies of anticancer effects associated with TRPV1-targeting agents question whether these are genuinely TRPV1-mediated. Indeed, it is puzzling why both TRPV1 agonists29-32 and antagonists29,30 administered independently would exert antiproliferatve effects against cancer cells through similar cell death mechanisms.29,68 It remains to be established whether there exist additional functionally different intracellular targets possessing structural requirements for binding similar to those at the vanilloid site on TRPV1. For example, vanilloids have indeed been shown to serve as ligands for cannabinoid receptors60 and both TRPV1 agonists and antagonists were found to inhibit mitochondrial function via concentration-dependent decreases in oxygen consumption and mitochondrial membrane potential.29 Thus, structural modifications of polygodial may have dissimilar effects on TRPV1 versus this alternative hypothetical target genuinely responsible for cancer cell death. This is supported by the results of the present work with the identification of compound 2, which compared with polygodial has significantly improved antiproliferative properties and yet lacks any effects on TRPV1, and compound 6, which appears to have TRPV1 agonistic properties superior to those of polygodial while lacking any antiproliferative effects.

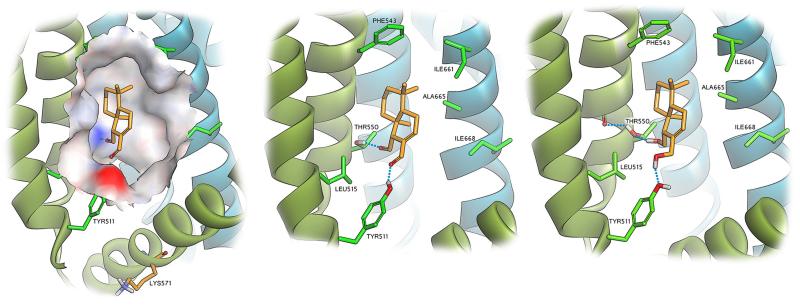

Computer modeling

In a search for a theoretical explanation of the experimental results obtained in the present investigation, the likely binding modes of polygodial (1) and polygodiol (6) were examined employing the cryo-EM derived structure of TRPV1 (protein data bank (PDB) ID 3J5R).70 These cryo-EM studies clearly identified the binding pocket of capsaicin and RTX, thereby allowing for molecular modeling studies to probe this region for the likely binding conformations of 1 and 6. Visual inspection of the binding pocket revealed a polar “southern region” providing possible hydrogen bonding interactions with the side chains of Tyr511 and Thr550, while the “northern region” of the pocket is predominantly apolar (Figure 7 left). Initial docking studies of 1 and 6 suggested that the preferred orientation of the ligands was indeed to facilitate hydrogen bonding to the side chains of Tyr511 and Thr550, via the carbonyls and hydroxyls of 1 and 6 respectively. Moreover, the hydrophobic regions of 1 and 6 were orientated towards the northern hydrophobic region of the pocket. However, visual critique of the binding mode suggested that for both 1 and 6, the binding poses were sub-optimal, with large parts of the molecules’ hydrophobic portions not well accommodated within the capsaicin binding pocket. Given the poor resolution of the TRPV1 structure, optimization of the binding pocket was warranted and to this end 1 was manually manipulated to a better fit within the pocket (by visual inspection) and the TRPV1-polygodial structure was subjected to a minimization employing fixed atom constraints of the protein backbone (not including residues within 7Å of 1) and a GB implicit solvation model. The resulting TRPV1 structure exhibited a 0.66Å root-mean-square deviation (RMSD, residues within the binding pocket) from the original structure. Docking of 1 and 6 into the refined TRPV1 structure now resulted in more sensible poses given the nature of the binding pocket, and provides an explanation for the measured binding affinities for the two structures. In the case of 1 (Figure 7 middle), the compound is well accommodated in the capsaicin pocket with the aldehyde functionalities orientated towards the southern more polar region of the pocket. Hydrogen bonding is observed for the aldehyde functionalities to the side chains of Tyr511 and Thr550, with the latter serving as hydrogen bond donors. In addition, the hydrophobic portion of 1 is accommodated in the northern apolar region of the pocket. Of interest is the fact that located at the southernmost point of the binding pocket is a lysine residue Lys571 (Figure 7 left). Although the side chain of this residue is not orientated toward the binding pocket, its close proximity to the aldehyde functionalities of 1 (≈10 Å) may account for the observed irreversible binding. The predicted binding pose for diol 6 differs from that of 1 in that the two alcohol functionalities can behave as either hydrogen bond donors or acceptors (Figure 7 right). For the hydrogen bonding interaction with the side chain of Tyr511 this is of no consequence, but regarding the hydrogen bonding to Thr550, it is here where the significantly stronger measured binding of 6 (in comparison to 1) to TRPV1 might be explained. In the case of 1, in order to facilitate double hydrogen bonding interactions, the side chains of both Tyr511 and Thr550 must act as donors. However, in the case of Thr550 in the apo form of the protein, this alcohol side chain forms a hydrogen bond to the amide carbonyl of Ala546. In order to form a hydrogen bond to the carbonyl of 1, the hydrogen bond to Ala546 must be sacrificed. However, in the case of the diol 6, the hydrogen bond between Thr550 and Ala546 need not be undone as 6 may form a hydrogen bond to the alcohol of Thr550, as a hydrogen bond donor. Docking of 9-epipolygodial (2) interestingly revealed that inversion of stereochemistry at C9 results in a pose incapable of facilitating both hydrogen bonding interactions. Hydrogen bonding only to the less preferred Thr550 (as donor) was observed and this may explain the substantially reduced TRPV1 activity.

Figure 7.

Molecular modeling showing the capsaicin binding region of TRPV1 with a solvent interpolated charge surface containing docked polygodial (1) and the close proximity of Lys571 (Left). Hydrogen bonding interactions to Tyr511 and Thr550 are observed for docked 1 (middle). Polygodiol 6 (right) docked within the pocket assumes a similar pose; however, the ability to act as a hydrogen bond donor to Thr550 means that this residue can maintain its structural hydrogen bonding interaction to Ala546.

Conclusion

Despite a safety concern involving potential tissue damage or haptenization of proteins eliciting an immune response, covalent drugs have been approved as treatments for diverse clinical applications and made a major impact on human health.71-73 For example, an estimated 80 billion tablets of aspirin are consumed annually in the United States and a number of blockbuster drugs, such as clopidogrel, lansoprazole and esomeprazole, are covalent inhibitors.73 Furthermore, covalent inhibitors are of key importance in the treatment of cancer and may be more effective in eradicating drug-resistant tumor cells.74 Thus, mutations in the binding site of a drug target represent an important cancer cell resistance mechanism and it has been noted that irreversible inhibitors maintain activity against such mutations caused by the treatment with reversible inhibitors.74 In one experimental confirmation of this proposal, treatment of NSCLC patients with reversible epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors produced a good initial response but then led to a relapse in ca. 50% of patients due to the development of resistance involving the expression of EGFR with mutations at T790M and/or L858R in the ATP binding site.74,75 The NSCLC cell line harboring the T790M–L858R double-mutant form of EGFR, was not affected by a panel of reversible inhibitors, but was by contrast significantly affected by irreversible inhibitors.74,76 The effectiveness of irreversible inhibitors against resistant mutants may lie in the fact that mutations generally only affect the rate of the covalent complex formation, and given sufficient exposure time, even mutated protein targets that react considerably more slowly will become irreversibly inactivated.73

The present work has led to the identification of 9-epipolygodial, an analogue of widely studied polygodial, which is more potent than polygodial by a factor of 20 against all cancer cells in the panel used in this work. Encouragingly, this compound retained activity against a significant number of drug-resistant cell lines that it was challenged with. Furthermore, the experimental results in our chemical system point to the fact that this compound likely works through a covalent inhibition of its anticancer target by forming a pyrrole adduct with a lysine residue. Such mode of reactivity in covalent target inhibition is greatly under-studied in the literature. It is likely however that this type of reactivity toward a lysine residue over the common imine formation, may lead to a higher selectivity for the target site, and thus reduced off-target effects. Indeed, a more complex chemical mechanism of the Paal-Knorr pyrrole condensation over the simple imine formation may be possible only at select protein binding sites capable of catalyzing this multistep transformation. In support of this reasoning, polygodial’s therapeutic application to control Candida albicans infections is well tolerated by most patients.13

Finally, this work also resulted in the discovery of non-toxic TRPV1 agonists, such as polygo-11,12-diol. Given the considerable interest in the medicinal chemistry community toward the exploitation of TRPV1-targeting agents as anti-nociceptives14-18,21-24 and the cytotoxicity associated with some of the studied compounds,27-32 these findings could be significant.

Experimental Section

General Experimental

All reagents, solvents and catalysts were purchased from commercial sources (Acros Organics and Sigma-Aldrich) and used without purification. All reactions were performed in oven-dried flasks open to the atmosphere or under nitrogen or argon and monitored by thin layer chromatography (TLC) on TLC precoated (250 μm) silica gel 60 F254 glass-backed plates (EMD Chemicals Inc.). Visualization was accomplished with UV light, iodine and p-anisaldehyde stains. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker 400 spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are reported in ppm relative to the TMS internal standard. Abbreviations are as follows: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet). The synthesized compounds are at least 95% pure according to an HPLC/MS analysis. Polygodial (1) was purchased from VWR.

Compound 2

To a solution of 1 (3 mg, 0.0128 mmol) in dry toluene (1.5 mL) were added 4A molecular sieves and PTSA (cat.). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 40 h. Solid NaHCO3 was added to the reaction mixture and stirred for 10 minutes, filtered and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by preparative TLC (8/92 EtOAc/Hexane) to obtain 1.2 mg of 2 (40% yield); 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 9.69 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 9.19 (s, 1H), 6.20 (dd, J = 4.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 1.96 – 1.88 (m, 1H), 1.62 – 1.51 (m, 1H), 1.45 – 1.39 (m, 2H), 1.34 – 1.25 (m, 2H), 1.20 – 1.12 (m, 2H), 0.96 – 0.87 (m, 2H), 0.65 (s, 3H), 0.63 (s, 3H), 0.57 (d, J = 0.7 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 202.2, 192.8, 153.4, 137.4, 58.5, 44.2, 42.0, 37.7, 37.1, 32.9, 32.7, 25.5, 21.9, 21.5, 18.4; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H22NaO2 (M+Na) 257.1517, found 257.1519.

Compound 5c

To a solution of 1 (3 mg, 0.0128 mmol) and 4-nitroaniline (1.9 mg, 0.014 mmol) in THF (2 mL) was added AcOH (4.3 μL, 0.077 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20h. After completion of the reaction, as monitored by TLC, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure and co-distilled with toluene. The crude product was purified by preparative TLC (15/85 EtOAc/Hexane) to obtain 2.4 mg of 5c (56% yield); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.27 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (dd, J = 2.1, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 6.55 (dd, J = 9.4, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 5.89 (dd, J = 9.4, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 2.12 (t, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), 2.08 – 2.01 (m, 1H), 1.81 – 1.72 (m, 1H), 1.69 – 1.59 (m, 4H), 1.09 (s, 3H), 1.05 (s, 3H), 0.99 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.4, 139.2, 128.7 (2C), 125.6 (2C), 123.5, 120.4, 118.2, 113.3, 110.5, 100.0, 53.1, 41.3, 36.4, 33.0, 29.7, 22.3, 21.6, 18.8, 14.1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H25N2O2 (M+H) 337.1916, found 337.1916.

Compound 6

To a solution of 1 (3 mg, 0.0128 mmol) in MeOH (2 mL) was added sodium borohydride (1.0 mg, 0.027 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. After completion of the reaction, as monitored by TLC, water was added to the reaction mixture and MeOH was evaporated. The reaction mixture was diluted with ethyl acetate and organic phase was washed with 1N HCl and water, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by preparative TLC (10/90 EtOAc/Hexane) to obtain 2.4 mg of 6 (80% yield); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.83 – 5.78 (m, 1H), 4.38 – 4.32 (m, 1H), 3.99 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (dd, J = 10.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (dd, J = 10.9, 8.2 Hz, 1H), 2.86 (brs, 1H), 2.14 (brs, 1H), 2.13 – 2.04 (m, 1H), 2.01 – 1.83 (m, 2H), 1.59 – 1.39 (m, 3H), 1.28 – 1.11 (m, 4H), 0.88 (s, 3H), 0.87 (s, 3H), 0.76 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 136.9, 127.6, 67.5, 61.5, 54.5, 49.4, 42.0, 39.3, 35.6, 33.2, 33.0, 23.6, 21.9, 18.8, 14.5; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H26NaO2 (M+Na) 261.1830, found 261.1829.

Compound 7

To a solution of 1 (3 mg, 0.0128 mmol) and hydrazine hydrate (0.7 μL, 0.014 mmol) in MeOH (1 mL) were added 4A molecular sieves. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 h. After completion of the reaction, as monitored by TLC, the reaction mixture was filtered and filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by preparative TLC (4/96 MeOH/CHCl3) to obtain 2.8 mg of 7 (95% yield); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 8.84 (s, 1H), 2.99 – 2.90 (m, 1H), 2.82 (ddd, J = 18.7, 11.1, 7.7 Hz, 1H), 2.37 – 2.31 (m, 1H), 2.06 – 1.98 (m, 1H), 1.86 – 1.65 (m, 3H), 1.58 – 1.51 (m, 1H), 1.42 (td, J = 12.7, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 1.31 – 1.23 (m, 2H), 1.23 (d, J = 0.7 Hz, 3H), 0.98 (s, 3H), 0.95 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 152.2, 148.3, 145.8, 135.8, 49.5, 41.2, 36.95, 36.4, 33.4, 33.0, 26.9, 24.2, 21.5, 18.6, 17.7; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H23N2 (M+H) 231.1861, found 231.1861.

Compound 8

To a suspension of raney nickel (21.0 mg) in water was added 1 (3 mg, 0.0128 mmol) in THF (2 mL). The resultant mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 h under hydrogen atmosphere using balloon. After completion of the reaction, as monitored by TLC, the reaction mixture was filtered through silica pad. The bed was washed several times with Et2O and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to obtain 2.9 mg of 8 (95% yield); 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.97 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 5.38 – 5.31 (m, 1H), 2.41 – 2.35 (m, 1H), 2.25 – 2.18 (m, 1H), 2.06 (s, 1H), 1.86 – 1.74 (m, 1H), 1.52 – 1.40 (m, 3H), 1.35 – 1.31 (m, 1H), 1.31 – 1.27 (m, 1H), 1.12 – 1.00 (m, 4H), 0.78 (s, 3H), 0.74 (s, 3H), 0.72 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C15H24NaO2 (M+Na) 259.1674, found 259.1674.

Compound 9

To a solution of 2 (1 mg, 0.0043 mmol) in dichloromethane (2 mL) was added methyl (triphenylphosphoranylidene)`acetate (7.1 mg, 0.0021 mmol). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 h. After completion of the reaction, as monitored by TLC, the reaction mixture was filtered and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by preparative TLC (9/91 EtOAc/Hexane) to obtain 1.1 mg of 9 (90% yield); 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 9.33 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 6.16 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 5.84 – 5.79 (m, 1H), 3.44 (s, 3H), 2.63 – 2.59 (m, 1H), 1.91 – 1.82 (m, 1H), 1.66 – 1.58 (m, 1H), 1.44 – 1.39 (m, 2H), 1.25 – 1.13 (m, 5H), 0.65 (s, 6H), 0.59 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, C6D6) δ 200.3, 168.0, 146.4, 141.4, 132.6, 117.1, 62.5, 51.1, 44.4, 42.2, 37.6, 36.4, 32.9, 32.7, 25.4, 21.8, 18.7, 14.2; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C18H26NaO3 (M+Na) 313.1780, found 313.1779.

General procedure for acetals 10-16

To a solution of 1 (3 mg, 0.0128 mmol) in dry toluene (2 mL) were added a selected alcohol (0.5 mL), 4A molecular sieves and PTSA (cat.). The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 h. Solid NaHCO3 was added and the reaction mixture was stirred for 10 minutes, filtered and the filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by preparative TLC (8/92 EtOAc/Hexane) to obtain acetal products (10-16).

Compound 10a

35%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.90 – 5.86 (m, 1H), 5.68 – 5.65 (m, 1H), 5.18 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.99 – 3.86 (m, 2H), 3.55 – 3.45 (m, 2H), 2.48 – 2.42 (m, 1H), 2.03 – 1.93 (m, 1H), 1.84 – 1.71 (m, 2H), 1.52 – 1.42 (m, 1H), 1.35 – 1.25 (m, 5H), 1.19 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.17 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 0.87 (s, 3H), 0.80 (s, 3H), 0.74 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H32NaO3 (M+Na) 331.2249, found 331.2248.

Compound 10b

45%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.59 – 5.56 (m, 1H), 5.36 (s, 1H), 5.14 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1H), 3.98 – 3.83 (m, 2H), 3.57 – 3.44 (m, 2H), 2.76 – 2.70 (m, 1H), 1.95 – 1.86 (m, 1H), 1.74 – 1.62 (m, 2H), 1.50 – 1.43 (m, 1H), 1.35 – 1.27 (m, 4H), 1.26 – 1.17 (m, 7H), 0.79 (s, 3H), 0.76 (s, 3H), 0.70 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H32NaO3 (M+Na) 331.2249, found 331.2248.

Compounds 11a+b (1:1.5 mixture)

80%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.92 – 5.87 (m, 1H), 5.71 – 5.67 (m, 1H), 5.59 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.1 Hz, 1.5H), 5.39 – 5.37 (m, 1.5H), 5.20 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 5.15 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 1.5H), 4.03 – 3.86 (m, 5H), 3.56 – 3.43 (m, 5H), 2.78 – 2.71 (m, 1.5H), 2.50 – 2.43 (m, 1H), 2.05 – 1.79 (m, 5H), 1.71 – 1.58 (m, 12.5H), 1.54 – 1.39 (m, 12H), 1.39 – 1.22 (m, 11H), 1.19 – 1.13 (m, 2H), 0.95 – 0.85 (m, 18H), 0.81 (s, 3H), 0.80 (s, 4.5H), 0.78 (s, 4.5H), 0.75 (s, 3H), 0.71 (s, 4.5H). [Total number of protons = 100H [40H (40H × 1.0) of 11a + 60H (40H × 1.5) of 11b]; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C23H40NaO3 (M+Na) 387.2875, found 387.2879.

Compound 12a

40%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.88 – 5.84 (m, 1H), 5.73 – 5.70 (m, 1H), 5.27 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H), 4.03 – 3.89 (m, 2H), 2.47 – 2.41 (m, 1H), 2.05 – 1.96 (m, 1H), 1.89 – 1.73 (m, 2H), 1.51 (dt, J = 13.3, 2.9 Hz, 1H), 1.40 – 1.29 (m, 11H), 1.15 – 1.09 (m, 6H), 0.90 (s, 3H), 0.81 (s, 3H), 0.75 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H36NaO3 (M+Na) 359.2562, found 359.2560.

Compound 13a

35%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.74 – 5.70 (m, 1H), 5.34 (s, 1H), 4.90 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.86 – 3.71 (m, 2H), 3.57 – 3.42 (m, 2H), 2.25 – 2.19 (m, 1H), 1.89 – 1.80 (m, 1H), 1.68 – 1.60 (m, 2H), 1.32 – 1.28 (m, 2H), 1.27 – 1.23 (m, 2H), 1.14 – 1.02 (m, 2H), 0.73 (s, 3H), 0.70 (s, 3H), 0.67 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H26F6KO3 (M+K) 455.1423, found 455.1423.

Compound 13b

55%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.43 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 5.09 (s, 1H), 4.90 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.80 – 3.65 (m, 2H), 3.63 – 3.44 (m, 2H), 2.52 – 2.46 (m, 1H), 1.83 – 1.74 (m, 1H), 1.60 – 1.46 (m, 2H), 1.30 – 1.21 (m, 2H), 1.09 – 0.89 (m, 4H), 0.72 (s, 3H), 0.68 (s, 3H), 0.57 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, C6D6) δ 136.0, 127.4, 125.7, 122.8, 106.5, 104.0, 65.3 (d), 63.9 (d), 57.7, 49.2, 42.2, 39.3, 32.9, 32.4, 29.8, 23.6, 21.4, 18.6, 14.1; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C19H26F6KO3 (M+K) 455.1423, found 455.1423.

Compound 14b

60%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.29 – 7.24 (m, 4H), 7.06 – 6.97 (m, 4H), 5.57 – 5.52 (m, 1H), 5.34 (s, 1H), 5.15 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (dd, J = 24.7, 12.3 Hz, 2H), 4.35 (d, J = 12.2 Hz, 2H), 2.78 – 2.72 (m, 1H), 1.98 – 1.86 (m, 1H), 1.72 – 1.61 (m, 1H), 1.46 – 1.38 (m, 2H), 1.22 – 1.10 (m, 3H), 1.10 – 0.96 (m, 2H), 0.78 (s, 3H), 0.73 (s, 3H), 0.69 (s, 3H); HRMS (ESI) calcd for C29H34Br2NaO3 (M+Na) 611.0772, found 611.0791.

Compounds 15a + b (1.0:1.7 mixture)

80%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.93 – 5.87 (m, 1H), 5.74 – 5.70 (m, 1H), 5.58 – 5.53 (m, 1.7H), 5.40 (s, 1.7H), 5.24 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 5.19 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1.7H), 4.04 – 3.94 (m, 5H), 3.79 – 3.67 (m, 5H), 3.61 – 3.33 (m, 11H), 3.20 (s, 5H), 3.18 (s, 5H), 3.15 (s, 3H), 3.14 (s, 3H), 2.76 – 2.70 (m, 1.7H), 2.47 – 2.41 (m, 1H), 1.95 – 1.83 (m, 4H), 1.75 – 1.62 (m, 2H), 1.53 – 1.42 (m, 2H), 1.42 – 1.25 (m, 8H), 1.27 – 1.19 (m, 4H), 1.15 – 1.01 (m, 6H), 0.87 (s, 3H), 0.79 (s, 3H), 0.77 (s, 5H), 0.73 (s, 5H), 0.73 (s, 3H), 0.70 (s, 5H). Total number of protons = 97H [36H (36H × 1.0) of 15a + 61H (36H × 1.7) of 15b]. HRMS (ESI) calcd for C21H36NaO5 (M+Na) 391.2460, found 391.2460.

Compounds 16a + b (1:1 mixture)

75%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.90 – 5.82 (m, 1H), 5.63 – 5.53 (m, 2H), 5.30 (s, 1H), 5.14 – 5.05 (m, 2H), 3.97 – 3.75 (m, 4H), 3.54 – 3.32 (m, 4H), 2.72 – 2.62 (m, 1H), 2.45 – 2.36 (m, 1H), 2.10 – 1.86 (m, 8H), 1.82 – 1.74 (m, 4H), 1.73 – 1.50 (m, 16H), 1.49 – 1.26 (m, 8H), 1.26 – 0.92 (m, 10H), 0.88 – 0.68 (m, 18H). Total number of protons = 80H (40H of 16a + 40H of 16b)]; HRMS (ESI) calcd for C27H40NaO3 (M+Na) 435.2875, found 435.2878.

Cell culture

Human cancer cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), the European Collection of Cell Culture (ECACC, Salisbury, UK) and the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). Human mammary carcinoma MCF-7 cells were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. The U87 cells (ATCC HTB-14) were cultured in DMEM culture medium, while the A549 cells (DSMZ ACC107) were cultured in RPMI culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. The GBM Hs683 (ATCC HTB-138) cells were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. The human uterine sarcoma MES-SA and MES-SA/Dx5 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS with MES SA/Dx5 maintained in the presence of 500 nM Doxorubicin (Sigma). SKMEL-28 cells (ATCC HTB72) and U373 GBM cells (ECACC 08061901) were cultured in RPMI culture medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. Cell culture media were supplemented with 4 mM glutamine (Lonza code BE17-605E), 100 μg/mL gentamicin (Lonza code 17-5182), and penicillin-streptomycin (200 units/ml and 200 μg/ml) (Lonza code 17-602E). The MDA-MB-231 (ATCC HTB-26) epithelial mammary adenocarcinoma cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM; Invitrogen) containing 5% fetal calf serum (FCS, Cambrex), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 0.06% HEPES (Invitrogen) and penicillin (50 IU/ml)/ streptomycin (50 lg/ml; Invitrogen) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Transformed mouse NPCs were cultured in suspension under neurosphere conditions at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 in DMEM F12 (Invitrogen 11320-074) supplemented with 1× B27 supplement (Invitrogen 17504-044), 5% penicillin-streptomycin (Biochrom 10378-017), 10 ng/ml EGF (R&D systems 236-EG), 10 ng/ml FGF (PeproTech 100-18B).

Antiproliferative Properties

Antiproliferative properties of the synthesized compounds were evaluated by the MTT assay.77-79 All compounds were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of either 100 mM or 50 mM prior to cell treatment. The cells were trypsinized and seeded at various cell concentrations depending on the cell type. The cells were grown for 24 h to 72 h, treated with compounds at concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 100 μM and incubated for 24, 48 or 72 h in 100 or 200 μL media depending on the cell line used. The number of experiments and replicates varied depending on the cell line. Cells treated with 0.1% DMSO were used as a negative control; 1 μM PAO was used as a positive control.

Selection of Doxorubicin Resistant Cells

Selection of the MES-SA/Dx5 cell line was done according to Harker et al.55 The cells were split and allowed to adhere overnight. The next day cells were initially exposed to doxorubicin (DOX) at the concentration of 100 nM, which represented the GI50 concentration. The cells were maintained at this DOX concentration until their growth rate reached that of the untreated cells. The DOX concentration was then increased in two-fold increments following the same growth criteria at each concentration to a final DOX concentration of 500 nM. Each new DOX concentration required approximately 2 passages to reach the growth rate of the untreated cells.

CytoTox-Fluor™ Cytotoxicity Assay

The CytoTox-Fluor cytotoxicity assay from Promega has been used according to manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 0,015 ×106 cells/well were plated in 24 well-plates in 450 μl (5 replicates per condition) then they received 50 μl of culture medium (DMEM-F12 without phenol red) supplemented with the drugs or respective vehicle control. After 24 hours of incubation at 37 °C, 20 μl of cell suspension was transferred to a black 384 well-plate and mixed with 20 μl of bis-AAF-R110 substrate dilution. After 2 hours of incubation at 37 °C, the fluorescence intensity was measured using the Tecan InfiniteF200 fluorescence plate reader (485 nm Ex/520 nm Em). Blank was subtracted from all wells and the fluorescence read-out for untreated cells (vehicle control) was normalized to 1. Read-outs from cells receiving different treatment conditions were normalized to those of untreated cells and fold change of relative cytotoxicity compared to untreated cells was calculated for each well. Outliers were detected and omitted, if any, using the Grubbs test. Graphs were generated using the GraphPad Prism software.

[3H]-Resiniferatoxin Binding Assay

To evaluate the possible affinity of different analogues to the vanilloid site of TRPV1, a [3H]-resiniferatoxin ([3H]-RTX) binding assay was performed as previously described.80,81 Briefly, rats spinal cord were homogenized in buffer A (pH 7.4, 5 mM KCl, 5.8 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.75 mM CaCl2, 137 mM sucrose, and 10 mM HEPES) and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 1000g at 4 °C and the supernatant was further centrifuged for 30 min at 35,000g at 4 °C. The resulting pellets were than resuspended in buffer A and frozen until assayed. The binding reaction was performed in a final volume of 500 μL, containing buffer A (plus 0.25 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, BSA), membranes (0.5 mg/mL), and 2 nM [3H]-RTX in the presence or absence of polygodial analogues (10 μM). For the measurement of the nonspecific binding, 100 μM nonradioactive RTX were included used. The reaction was started by incubating tubes at 37 °C during 60 minutes, and stopped by transferring the tubes to ice bath and adding 100 μg of bovine α1-acid glycoprotein (to reduce nonspecific binding). Finally, the bound and free membranes [3H]-RTX were separated by centrifuging for 30 min at 35,000g at 4 °C. The pellet was used to quantify the scintillation counting. The specific binding was calculated as the difference of the total and nonspecific binding and the results were measured as % of specific binding.

Intracellular Ca2+ measurements

Cells were grown on glass coverslips for fluorescence imaging. The cytosolic calcium was measured using Fura-2-loaded cells. Cells were loaded for 45 min at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air with 3.3 μM Fura-2/AM prepared in saline solution. Fluorescence was excited at 350 and 380 nm alternately using a monochromator (Polychrome IV; TILL Photonics, Planegg, Germany), and captured by a Cool SNAP HQ camera (Princeton Instruments, France) after filtration through a long-pass filter (510 nm). Metafluor software 7.0 (Molecular Devices) was used for acquisition and analysis. All recordings were carried out at room temperature. The cells were perfused with the saline solutions comprising of (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, HEPES 10 and Glucose 5 (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH).

Electrophysiological recordings

TRP currents were recorded using the conventional technique of patch-clamp in the whole-cell configuration. Briefly, holding membrane potential was held to −40 mV, and currents were elicited by a ramp depolarization from −100 to +100 mV for 350 msec. Interval between each ramp depolarization was 10 sec. The patch pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were made from hematocrit glass using a vertical puller (P30 vertical micropipette puller; Sutter Instrument). The following extracellular solution was used (in mM): Na-gluconate, 140; K-gluconate, 5; Mg-gluconate, 2; Ca-gluconate, 2; HEPES, 10; glucose, 5 and TEA-Cl, 5 (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). The following intrapipette solution was used (in mM): Cs-gluconate, 145; Na-gluconate, 8; EGTA, 10; Mg-gluconate 3 and HEPES, 10 (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). Signals were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) combined with a 1322A digidata (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Electrophysiological protocols and analyses were made using pClamp 10, Clampfit (both by Molecular Devices) and Origin 6.0 (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA). All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Computer modeling

Molecular modelling was performed using Discovery Studio 4.5 (DS). The receptor template was obtained from the PDB (ID 3J5R) and chains B and D were retained for the simulations. Protein preparation was carried out using the Prepare Protein protocol launched from within DS. All docking simulations were carried out using a modified CDocker protocol with pregeneration of ligand conformations to adequately sample conformational space. Minimizations were carried out within DS employing the CHARMm forcefield (version 39.1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103451), National Cancer Institute (CA186046-01A1), Welch Foundation (AI-0045), and National Science Foundation (NSF award 0946998). SR and LF acknowledge their NMT Presidential Research Support. LF acknowledges Samantha Saville and National Science Foundation (NSF award IIA-1301346). RK is a director of research with the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS; Belgium). SCP and WvO gratefully acknowledge support from the National Research Foundation (NRF)-South Africa, as well as Stellenbosch University. The authors are grateful to Anntherese Kornienko for her help with creating Figure 2.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at:

References

- 1.Ohsuka A. Nippon Kagaku Zasshi. 1963;84:748–752. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonassohn M, Sterner O. Trends Org. Chem. 1997;6:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caprioli V, Cimino G, Colle R, Gavagnin M, Sodano G, Spinella A. J. Nat. Prod. 1987;50:146–151. doi: 10.1021/np50050a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakanishi K, Kubo I. Israel J. Chem. 1977;16:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cimino G, De Rosa S, De Stefano S, Sodano G. Comp. Eiorhem. Pbysiol. 1982;73B:471–474. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubo I, Ganjian I. Experientia. 1981;37:1063–1064. doi: 10.1007/BF02085009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubo I, Nakanishi K. In: Geissbuhler H, editor. Pergamon Press; New York: 1979. p. 284. Part 2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cimino G, Spinella A, Sodano G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4151–4152. [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Ischia M, Prota G, Sodano G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:3295–3298. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cimino G, Sodano G, Spinella A. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:5401–5410. [Google Scholar]

- 11.da Cunha FM, Frode TS, Mendes GL, Malheiros A, Filho VC, Yunes RA, Calixto JB. Life Sci. 2001;70:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SH, Lee JR, Lunde CS, Kubo I. Planta Medica. 1999;65:204–208. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-13981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterner O, Szallasi A. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:459–465. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andre E, Ferreira J, Malheiros A, Yunes RA, Calixto JB. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:590–597. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monica CD, De Petrocellis L, Di Marzo V, Landi R, Izzo I, Spinella A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007;17:6444–6447. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andre E, Campi B, Trevisani M, Ferreira J, Malheiros A, Yunes RA, Calixto JB, Geppetti P. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;71:1248–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Acunto M, Monica CD, Izzo I, De Petrocellis L, di Marzo V, Spinella A. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:9785–9789. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwasaki Y, Tanabe M, Kayama Y, Abe M, Kashio M, Koizumi K, Okumura Y, Morimitsu Y, Tominaga M, Ozawa Y, Watanabe T. Life Sci. 2009;85:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendes GL, Santos AR, Campos MM, Tratsk KS, Yunes RA, Cechinel Filho V, Calixto JB. Life Sci. 1998;63:369–381. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. Nature. 1997;389:816–824. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Julius D, Basbaum AI. Nature. 2001;413:203–210. doi: 10.1038/35093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trevisani M, Smart D, Gunthorpe MJ, Tognetto M, Barbieri M, Campi B, Amadesi S, Gray J, Jerman JC, Brough SJ, Owen Smith DGD, Randall AD, Harrison S, Bianchi A, Davis JB, Geppetti P. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:546–551. doi: 10.1038/nn0602-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis JB, Gray J, Gunthorpe MJ, Hatcher JP, Davey PT, Overend P, Harries MH, Latcham J, Clapham C, Atkinson K, Hughes SA, Rance K, Grau E, Harper AJ, Pugh PL, Rogers DC, Bingham S, Randall A, Sheardown SA. Nature. 2000;405:183–187. doi: 10.1038/35012076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caterina MJ, Julius D. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;24:487–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Premkumar LS, Bishnoi M. Curr. Topics Med. Chem. 2011;11:2192–2209. doi: 10.2174/156802611796904834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gkika D, Prevarskaya N. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1793:953–958. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartel M, di Mola FF, Selvaggi F, Mascetta G, Wente MN, Felix K, Giese NA, Hinz U, Di Sebastiano P, Buchler MW, Friess H. Gut. 2006;55:519–528. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.073205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stock K, Kumar J, Synowitz M, Petrosino S, Imperatore R, Smith ES, Wend P, Purfürst B, Nuber UA, Gurok U, Matyash V, Wälzlein JH, Chirasani SR, Dittmar G, Cravatt BF, Momma S, Lewin GR, Ligresti A, De Petrocellis L, Cristino L, Di Marzo V, Kettenmann H, Glass R. Nat Med. 2012;18:1232–1238. doi: 10.1038/nm.2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Athanasiou A, Smith PA, Vakilpour S, Kumaran NM, Turner AE, Bagiokou D, Layfield R, Ray DE, Westwell AD, Alexander SPH, Kendall DE, Lobo DN, Watson SA, Lophatanon A, Muir KA, Guo DA, Bates TE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;354:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzales CB, Kirma NB, De La Chapa JJ, Chen R, Henry MA, Luo S, Hargreaves KM. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skrzypski M, Sassek M, Abdelmessih S, Mergler S, Grotzinger C, Metzke D, Wojciechowicz T, Nowak KW, Strowski MZ. Cellular Signal. 2014;26:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farfariello V, Liberati S, Morelli MB, Tomassoni D, Santoni M, Nabissi M, Giannantoni A, Santoni G, Amantini C. Chem. Biol. Inter. 2014;224:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allouche N, Apel C, Martin MT, Dumontet V, Guéritte F, Litaudon M. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:546–553. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tozyo T, Yasuda F, Nakai H, Tada H. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1992:1859–1866. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrero AF, Corte’s M, Manzaneda EA, Cabrera E, Chahboun R, Lara M, Rivas AR. J. Nat. Prod. 1999;62:1488–1491. doi: 10.1021/np990140q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anke H, Sterner O. Planta Med. 1991;57:344–346. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forsby A, Andersson M, Lewan L, Sterner O. Toxicol. In Vitro. 1991;5:9–14. doi: 10.1016/0887-2333(91)90043-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andersson M, Bocchio F, Sterner O, Forsby A, Lewan L. Toxicol. In Vitro. 1993;7:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0887-2333(93)90106-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montenegro I, Tomasoni G, Bosio C, Quinones N, Madrid A, Carrasco H, Olea A, Martinez R, Cuellar M, Villena J. Molecules. 2014;19:18993–19006. doi: 10.3390/molecules191118993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amarnath V, Anthony DC, Amarnath K, Valentine WM, Wetterau LA, Graham DG. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:6924–6931. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Gavin T, DeCaprio AP, LoPachin RM. Toxicol. Sci. 2010;117:180–189. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneimann MJ, Beaudry CM, Genung NE, Canham SM, Untiedt NL, Karanikolas BDW, Sutterlin C, Overman LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17494–17503. doi: 10.1021/ja207727h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barrrero AF, Cortes M, Manzaneda EA, Cabrera E, Chanboun R, Lara M, Rivas AR. J. Nat. Prod. 1999;62:1488–1491. doi: 10.1021/np990140q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuellar MA, Moreno LE, Preite M. ARKIVOC. 2003;10:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tozyo T, Yasuda F, Nakai H, Tada H. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1992:1859–1866. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keshmiri-Neghab H, Goliaei B. Pharm. Biol. 2014;52:124–128. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2013.832776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lefranc F, Nuzzo G, Hamdy NA, Fakhr I, Moreno L, Banuls Y, Van Goietsenoven G, Villani G, Mathieu V, van Soest R, Kiss R, Ciavatta ML. J. Nat. Prod. 2013;76:1541–1547. doi: 10.1021/np400107t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathieum A, Remmelink M, D’Haene N, Penant S, Gaussin JF, Van Ginckel R, Darro F, Kiss R, Salmon I. Cancer. 2004;101:1908–1918. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathieu V, Pirker C, Martin de Lasalle E, Vernier M, Mijatovic T, De Neve N, Gaussin JF, Dehoux M, Lefranc F, Berger W, Kiss R. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:3960–3972. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frolova LV, Magedov IV, Romero AE, Karki M, Otero I, Hayden K, Evdokimov NM, Banuls LMY, Rastogi SK, Smith WR, Lu SL, Kiss R, Shuster CB, Hamel E, Betancourt T, Rogelj S, Kornienko A. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:6886–6900. doi: 10.1021/jm400711t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aksenov AV, Smirnov AN, Magedov IV, Reisenaur MR, Aksenov NA, Aksenova IV, Nguyen G, Johnston RK, Rubin M, Kiss R, Mathieu V, Lefranc F, Correa J, Cavazos DA, Brenner AJ, Rogelj S, Kornienko A, Frolova LV. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:2206–2220. doi: 10.1021/jm501518y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saraswathy M, Gong SQ. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013;31:1397–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen GK, Duran GE, Mangili A. Br. J. Cancer. 2000;83:892–898. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geney R, Ungureanu M, Li D, Ojima I. Clinical Chem. Lab. Med. 2002;40:918–925. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harker WG, Sikic BI. Cancer Res. 1985;45:4091–4096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Singh SK, Hawkins C, Clarke ID, Squire JA, Bayani J, Hide T, Henkelman RM, Cusimano MD, Dirks BP. Nature. 2004;432:396–401. doi: 10.1038/nature03128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yuan X, Curtin J, Xiong Y, Liu G, Waschsmann-Hogiu S, Black KL, Yu JS. Oncogene. 2004;23:9392–9400. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galli R, Binda E, Orfanelli U, Cipelletti B, Gritti A, De Vitis S, Fiocco R, Foroni C, Dimeco F, Vescovi A. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7011–7021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee J, Kotliarova S, Kotliarov Y, Li A, Su Q, Donin NM, Pastorino S, Purow BW, Christopher N, Zhang W, Park JK, A H. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, Dewhirst MW, Bigner DD, Rich JM. Nature. 2006;444:756–760. doi: 10.1038/nature05236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, Tunici P, Ng H, Abdulkadir IR, Lu L, Irvin D, Black KL, Yu JS. Mol. Cancer. 2006;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Johannessen TC, Bjerkvig R, Tysnes BB. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:558–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma S, Lee TK, Zheng BJ, Chan KW, Guan XY. Oncogene. 2008;27:1749–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Purkait S, Jha P, Sharma MC, Suri V, Sharma M, Kale SS, Sarkar C. Neuropathol. 2013;33:405–412. doi: 10.1111/neup.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gan HK, Kaye AH, Luwor RB. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2009;16:748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guo P, Hu B, Gu W, Xu L, Wang D, Huang HJS, Cavenee WK, Cheng SC. Amer. J. Pathol. 2003;162:1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63905-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ligresti A, Moriello AS, Starowicz K, Matias I, Pisanti S, De Petrocellis L, Laezza C, Portella G, Bifulco M, Di Marzo V. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;318:1375–1387. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.105247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reilly CA, Taylor JL, Lanza DL, Carr BA, Crouch DJ, Yost GS. Toxicol. Sci. 2003;73:170–181. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sancho R, de la Vega L, Appendino G, Di Marzo V, Macho A, Munoz E. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;140:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cao E, Liao M, Cheng D, Julius D. Nature. 2013;504:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Potashman MH, Duggan ME. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:1231–1246. doi: 10.1021/jm8008597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robertson JG. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5561–5571. doi: 10.1021/bi050247e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Singh J, Petter RC, Baillie TA, Whitty A. Nature Rev. Drug. Disc. 2011;10:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nrd3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kwak EL, Sordella R, Bell DW, Godin-Heymann N, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Driscoll DR, Fidias P, Lynch TJ, Rabindran SK, McGinnis JP, Wissner A, Sharma SV, Isselbacher KJ, Settleman J, Haber DA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7665–7670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502860102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pao W, Miller VA, Politi KA, Riely GJ, Somwar R, Zakowski MF, Kris MJ, Varmus H. PLoS Med. 2005;2:225–235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carter TA, Wodicka LM, Shah NP, Velasco AM, Fabian MA, Treiber DK, Milanov ZV, Atteridge CE, Biggs WH, Edeen PT, Floyd M, Ford JM, Grotzfeld RM, Herrgard S, Insko DE, Mehta SA, Patel HK, Pao W, Sawyers CL, Varmus H, Zarrinkar PP, Lockhart DJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:11011–11016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504952102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dasari R, Banuls LMY, Masi M, Pelly SC, Mathieu V, Green IR, van Otterlo WAL, Evidente A, Kiss R, Kornienko A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:923–927. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dasari R, Kornienko A. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2014:160–165. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Scott R, Karki M, Reisenauer MR, Rodrigues R, Dasari R, Smith WR, Pelly SC, van Otterlo WAL, Shuster CB, Rogelj S, Magedov IV, Frolova LV, Kornienko A. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:1428–1435. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201300532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Szallasi A, Biro T, Modarres S, Garlaschelli L, Petersen M, Klusch A, Vidari G, Jonassohn M, De Rosa S, Sterner O, Blumberg PM, Krause JE. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;356:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rossato MF, Trevisan G, Walker CI, Klafke JZ, de Oliveira AP, Villarinho JG, Zanon RB, Royes LF, Athayde ML, Gomez MV, Ferreira J. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;81:544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.