ABSTRACT

The purpose of this matched case-control study was to investigate the social correlates of primary infertility among females aged 35 years or less. The study was conducted in the Clinics of Samarkand Medical Institute, Uzbekistan, among 120 infertile and 120 healthy women matched by age, residential area, and occupation from January to June 2009. Data were collected by face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire. Median duration of infertility was 10.0 months (interquartile range = 6.0–13.0). The rate of remarriage was 3.5 times higher among infertile women compared with healthy subjects. Insufficient family income, poor quality of life, life stress, and discontentment with daily routines as well as ‘bad’ relationships with family members (husband, mother- and father-in-law) were significant correlates of female infertility. Infertile women were more likely to underestimate the importance of sexual intimacy, and a negative attitude to sex. Female infertility is associated with various social correlates leading to higher remarriage rates and to further complicating the problem of infertility. Thus, a correction of women’s basic attitudes and their relationships to their surrounding social habitat should be an essential component of any program of infertility management.

Key Words: Female infertility, social correlates, relationship with family members, sexual intimacy

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined infertility as a failure to conceive over 12 months of exposure (which is a good practical guide to management), and leaves a longer term residual incidence of infertility of 10–15%.1) However, the chance to conceive is reduced almost twofold after the age of 35 years.1) Epidemiological data suggest that approximately 80 million people worldwide are infertile.2) WHO indicates the highest incidence in some regions of Central Africa where the infertility rate may reach 50%, compared to 20% in the Eastern Mediterranean region, and 11% in the developed world.3) Although infertility is a problem among both men and women, about one-third of infertility cases are caused exclusively by women’s problems, whereas one third are due to men, and the rest are attributed to a mixture of both or by problems unknown.4)

Infertility can have a serious impact on both the psychological well-being and the social status of women in the developing world.5) As a result of their infertile status, they suffer physical and mental abuse, neglect, abandonment, economic deprivation and social ostracism as well as exclusion from certain social activities and traditional ceremonies.6, 7) This becomes particularly traumatic with previous pregnancies that end in abortions, stillbirths and neonatal/infant deaths or in live births of daughters only.8) A survey conducted in Southern Ghana revealed that the majority (64%) of women felt stigmatized, and that higher levels of perceived stigma were associated with increased infertility-related stress as well as lower levels of education.9) Some findings from the qualitative analysis concerned a major difference between primary and secondary infertility in terms of its implications for the affected women.10)

It is convenient to divide the literature into articles which explore the possibility that infertility may have psychological causes (Psychogenic Hypothesis) and those which examine the psychological consequences of infertility (Psychological Consequences Hypothesis).11) Though the psychogenic hypothesis is now rejected by most researchers,11) several sources provided reliable evidence that certain social factors might further complicate infertility among women. Available evidence suggests that social factors, such as stress, anxiety or sudden weight loss after a crash diet inhibit normal gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion, leading to ovulation failure.12) The literature has clearly indentified a series of modifiable lifestyle factors, such as psychological stress, smoking, alcohol and caffeine consumption, poor diet, obesity, and insufficient exercise that could potentially impact fertility in the general population.13-17)

Infertility has much stronger negative consequences in developing countries compared with those in Western societies.18) In Uzbekistan where, traditionally, having children is mandatory in terms of family happiness, this problem acquires crucial social actuality. However, we could find no comprehensive study in Uzbekistan on the various social correlates of female infertility. Assessments of social consequences, including attitude to family income, family and social relations, lifestyle, quality of life, nutrition, and intimacy, play important roles in understanding the problem of female infertility on a wider scale. Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine the social correlates of female infertility in Uzbekistan.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A case-control study with 120 infertile (cases) and 120 healthy women (controls) was conducted in the Clinic of the Samarkand Medical Institute, Uzbekistan. Infertile patients were selected consecutively from infertile women admitted to the Gynecology Department during the six months from January to June 2009. The inclusion criteria for infertile patients were: 1) Women from 19 to 35 years of age, and 2) with a confirmed diagnosis of primary infertility. The diagnosis of infertility was based on the WHO definition of infertility as a failure to conceive over 12 consecutive months of regular, active, and unprotected sex. All cases were diagnosed by a gynecologist involved in infertility management in the hospital. Age 19 was determined as the lowest cut-off point since the age of legal permission to marry in Uzbekistan was set at 18. Since chance to conceive diminishes significantly after the age of 35,12, 19) that was accepted as the highest cut-off in our study.

The group of healthy women was randomly selected from those who gave birth in the Maternity Complex of the Samarkand Medical Institute’s clinic from January to June 2009. Known confounders of social correlates, such as the area of residence, age and occupation were taken as matching criteria for selecting the control group. Any evidence of infertility in the past was an exclusion criterion, as were women with a known infertile husband.

Data collection was done by face-to-face interviews using a researcher-developed structured questionnaire, and by medical examinations using a checklist. The questionnaire included closed-ended questions (except age and duration of infertility) on basic information about patients and clinical data, a woman’s self-rating of social status, and intimacy during their married life. Our checklist included physical and gynecological examination results recorded by the research team. There were 13 specific questions including a self-estimation of family income, life quality, nutrition quality, daily routine, life stress, relationships with a husband, parents-in-law and Mahalla members (a unit of the local community in Uzbekistan) as well as attitudes to intimacy after a diagnosis of infertility. A checklist and a questionnaire were developed, revised, and finalized after piloting among patients with and without infertility in the same department.

Each interview took place in a private setting either before or after consultation with a physician. Before answering specific questions, patients were informed about the meaning of each question to avoid information bias. For example, before asking ‘how do you estimate your nutrition quality?’, the interviewer briefly explained what ‘nutrition quality’ meant, i.e., the optimal balance of essential nutrients as well as timing between meals, etc.

The study aimed to focus on women’s self-rating of social variables rather than the actual state of such matters. For example, a self-rating of family income solely reflected a subject’s personal feelings towards their income with no relation to their actual income.

It was necessary to determine the definition of some variables such as quality of life, daily routine, life stress, and intimacy. Quality of life is a broad term used to evaluate the general well-being of individuals and societies over a wide range of contexts, including healthcare. In our study, “quality of life” was defined as women’s perceptions about widely-valued aspects of life, such as social well-being and happiness.20) Satisfaction with daily routine included women’s contentment with the sequence and volume of daily social activities (work, household chores, relaxing, etc.). “Life stress” was defined as a condition that resulted when person-environment transactions lead the person to perceive a difficulty to cope with the demands of a life.21) “Intimacy” in this study was used as a substitute for a woman’s sexual life. Under Uzbek norms, it was embarrassing for a woman to answer a direct question about her sexual life. To avoid such an awkward situation, we used the term ‘intimacy.’

The anonymity of a respondent’s identity was strictly preserved. Written informed consent was obtained from all the women before collecting data. They were ensured of full freedom to participate in the study or to decline to do so at any time without prejudice. Moreover, this study was ethically approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samarkand Medical Institute.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using the software Statistical Package for Social Science® (SPSS) for Windows, version 18 (SPSS Inc., Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistical tests were applied to all data. Continuous data were presented as the mean (±standard deviation [SD]) for normally distributed data, and as the median (interquartile range [IQR]) for non-normal data. Categorical data were expressed as numbers and percentages, while chi-square analyses were used to compare those categorical variables. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to identify various social correlates of infertility, such as socioeconomic factors (including family income, quality of life, satisfaction about daily routine, life stress, and quality of nutrition), relationship with family members and neighbors, and various aspects of attitudes towards intimacy using conditional logistic regression. All tests were two-tailed, with statistical significance fixed at the level of P < .05.

RESULTS

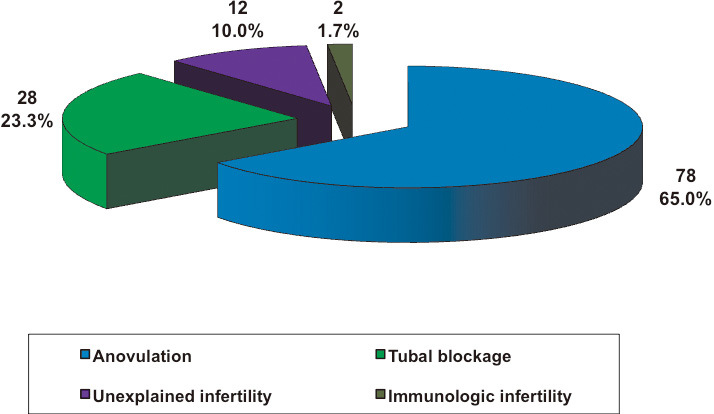

The main known cause of infertility was the anovulation diagnosed in 65.0% (78) of patients. Anovulation was associated with menstrual cycle disorders, algodysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia, general and genital infantilism and other conditions. Tubal blockage was diagnosed in 23.3%, immunologic factors in 1.7%, with the remaining 10.0% of women suffering unexplained infertility (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Clinical factors in female infertility

Women with infertility ranged between 19 and 35 (mean age 25.8 years), around ¾ of whom were aged 21 to 30. Residents of rural areas comprised 51.7%, while 48.3% were urban residents. Nearly half of the infertile women (47.5%) were service holders, 28.4% were industrial workers, and 15.8% were housewives. Median duration of infertility was 10.0 (IQR=6.0–13.0) months from the first diagnosis of infertility. There was no difference in the demographic data between women with infertility and those in the healthy group except for the order of marriage of women and their husbands (Table 1). Significantly more women (21.0%) were in their second marriage, which is more than three times higher than those in the comparison group (6.0%). This discrepancy was also found among men: 30.3% and 23.1% for the husbands of women in the infertile and comparison group, respectively (Table 1); however, the difference was not significant.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents

| Variables | Infertile group (n=120) |

Healthy group (n=120) |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Residential area | 0.897 | ||||

| Rural | 62 (51.7) | 63 (52.5) | |||

| Urban | 58 (48.3) | 57 (47.5) | |||

| Age groups (year) | 0.922 | ||||

| 19–20 | 9 (7.5) | 10 (8.3) | |||

| 21–30 | 91 (75.8) | 92 (76.7) | |||

| 31–35 | 20 (16.7) | 18 (15.0) | |||

| Mean (±standard deviation) | 25.8 (±3.9) | 25.4 (±3.6) | |||

| Duration of infertility (months)a | |||||

| Median (interquartile range) | 10.0 (6.0–13.0) | – | |||

| Occupation | 0.928 | ||||

| Housewife | 19 (15.8) | 17 (14.2) | |||

| Service holder | 57 (47.5) | 62 (51.7) | |||

| Industrial worker | 34 (28.4) | 31 (25.8) | |||

| Student | 10 (8.3) | 10 (8.3) | |||

| Order of marriage for women | .001 | ||||

| First marriage | 94 (79.0) | 110 (94.0) | |||

| Second marriage | 25 (21.0) | 7 (6.0) | |||

| Order of marriage for men (husband) | 0.214 | ||||

| First marriage | 83 (69.7) | 90 (76.9) | |||

| Second marriage | 36 (30.3) | 27 (23.1) |

aDuration of infertility was calculated from the first diagnosis of infertility after 12 months of unprotected sex.

Studying social correlates was based on a significant variety of factors including attitude to family income, self-rated quality of life and nutrition, self-estimation of daily routine, attitude to social environment and the evaluation of a woman’s attitude to sexual intimacy. Insufficient family income and the fear of poverty among women were significantly associated with infertility. Out of a total of 118 infertile women who responded, 59.3% estimated their income as ‘less than needed’ and ‘barely sufficient’, while in the comparison group only one third (32.2%) chose that answer (Table 2). ORs compared with the first category (‘excellent’) were 2.8 (95% CI = 1.2–6.8) and 3.1(95% CI = 1.1–8.5) for the ‘barely sufficient’ and ‘less than needed’ categories (P < .05). The same pattern was detected with self-estimations of life quality. When asked about their quality of life, 46.2% infertile women responded ‘not bad’ (in Uzbek informal speech ‘not bad’ actually means ‘not so good’) or ‘poor’ and which was 29.4% for the control group, with ORs 3.3 (95% CI = 1.6–6.4) and 3.8 (95% CI =1.2–11.5), respectively (P < .05).

Table 2.

Subjective self-rating of some socioeconomic factors by the respondents

| Social factors | Infertile group (n=120) |

Healthy group (n=120) |

ORa (95% CIb) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||||

| Family income | ||||||

| Excellent | 9 (7.6) | 19 (16.1) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Good | 39 (33.1) | 61 (51.7) | 1.6 (0.7–3.6) | 0.275 | ||

| Barely sufficient | 49 (41.5) | 27 (22.9) | 2.8 (1.2–6.8) | .019 | ||

| Less than needed | 21 (17.8) | 11 (9.3) | 3.1 (1.1–8.5) | .032 | ||

| Quality of life | ||||||

| Excellent | 15 (12.6) | 43 (36.1) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Good | 49 (41.2) | 41 (34.5) | 2.6 (1.4–4.8) | .003 | ||

| Not bad | 44 (37.0) | 29 (24.4) | 3.3 (1.6–6.4) | .001 | ||

| Poor | 11 (9.2) | 6 (5.0) | 3.8 (1.2–11.5) | .019 | ||

| Satisfaction with daily routines | ||||||

| Well contented | 32 (27.1) | 65 (55.1) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Moderate | 66 (56.0) | 44 (37.3) | 1.9 (1.2-2.9) | .004 | ||

| Not contented | 20 (16.9) | 9 (7.6) | 3.1 (1.4-7.1) | .008 | ||

| Self-assessment of life stress | ||||||

| No, never | 15 (12.6) | 45 (37.8) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Sometimes | 51 (42.9) | 43 (36.1) | 2.7 (1.5-4.9) | .002 | ||

| Yes, very often | 53 (44.5) | 31 (26.1) | 3.6 (1.9-7.0) | <.001 | ||

| Quality of nutrition | ||||||

| Good and rational | 6 (5.1) | 7 (5.9) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Moderate | 58 (49.6) | 68 (57.1) | 1.0 (0.3-3.0) | 0.976 | ||

| Poor and irrational | 53 (45.3) | 44 (37.0) | 1.4 (0.4-4.2) | 0.597 | ||

aOR, Odds ratio; bCI, Confidence interval.

A lack of contentment with their daily routine was another social correlate of infertility, with OR being 1.9 (95% CI = 1.2–2.9) between the ‘well contented’ and ‘moderate’, and 3.1 (95% CI = 1.4–7.1) between ‘well contented’ and ‘not contented’ categories (P < .05). Self assessments of life stress were especially important to demonstrate the relationship between social factors and female infertility. The number of subjects who ‘never’ experienced stress was three times higher in the healthy group compared with the infertile group, while the number of patients who felt stress ‘very often’ was almost twice as high among the infertile women. OR equalled to 2.7 (95% CI = 1.5–4.9) between the ‘no, never’ and ‘sometimes’, and 3.6 (95% CI = 1.9–7.0) between the ‘no, never’ and ‘yes, very often’ categories (P < .05). We could not find an association of female infertility with self-rated nutrition quality (Table 2).

The social environment within the family, and a poor relationship with family members were also found to be associated with women’s infertility. An assessment of participants’ relationships with their husbands, mothers-in-law, fathers-in-law, and members of the local community is illustrated in Table 3. As seen from the Table, the former three showed a significant association with women’s infertility. Inadequate relationships (combination of ‘bad’ and ‘not bad’) with husbands was mentioned by 63.2%, with mother-in-laws by 65.0%, and with father-in-laws by 66.7% of infertile women. The comparable numbers were 46.2%, 45.3% and 37.6%, respectively, in the healthy group. The ‘Not bad’ and ‘Bad’ categories were significant correlates of women’s infertility, compared with an ‘excellent’ relationship as a reference category, with ORs of 2.9 (95% CI = 1.2–6.9) and 3.6 (95% CI = 1.4–9.1), respectively, with P < .05. However, we did not find a significant association between infertility and women’s relationships with Mahalla (local community) members (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respondents’ self-rating of their relations with family members and neighbors

| Relationships | Infertile group (n=120) |

Healthy group (n=120) |

ORa (95% CIb) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||||

| With husband | ||||||

| Excellent | 8 (6.8) | 22 (18.8) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Good | 35 (29.9) | 41 (35.0) | 2.2 (1.0–5.3) | .067 | ||

| Not bad | 46 (39.3) | 36 (30.8) | 2.9 (1.2–6.9) | .014 | ||

| Bad | 28 (23.9) | 18 (15.4) | 3.6 (1.4–9.1) | .008 | ||

| With mother-in-law | ||||||

| Excellent | 6 (5.1) | 18 (15.4) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Good | 35 (29.9) | 46 (39.3) | 2.3 (0.8–6.4) | 0.107 | ||

| Not bad | 57 (48.8) | 40 (34.2) | 3.3 (1.2–8.9) | .018 | ||

| Bad | 19 (16.2) | 13 (11.1) | 3.3 (1.2–9.3) | .024 | ||

| With father-in-law | ||||||

| Excellent | 9 (7.7) | 19 (16.2) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Good | 30 (25.6) | 54 (46.2) | 1.3 (0.5–3.0) | 0.608 | ||

| Not bad | 62 (53.0) | 35 (29.9) | 2.5 (1.1–5.8) | .039 | ||

| Bad | 16 (13.7) | 9 (7.7) | 3.0 (1.1–8.5) | .036 | ||

| With Mahallac members | ||||||

| Excellent | 7 (5.9) | 8 (6.8) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Good | 53 (44.9) | 55 (47.0) | 1.2 (0.36–4.03) | 0.756 | ||

| Not bad | 45 (38.1) | 39 (33.4) | 1.5 (0.4–5.4) | 0.544 | ||

| Bad | 13 (11.1) | 15 (12.8) | 1.0 (0.3–4.2) | 0.952 |

aOR, Odds ratio; bCI, Confidence interval; cMahalla – a neighborhood unit in Uzbekistan.

One of the main points of interest was the assessment of infertile women’s attitude to sexual intimacy on the basis of three questions related to that topic. To determine their attitude to the issue in general, the first question was ‘Is sexual intimacy important?’ ORs between the reference category (‘very important’) and the other two categories were 1.8 (95% CI = 1.1–3.0) and 1.7 (95% CI = 1.1–2.9), indicating a statistically significant association between women’s underestimation of sexual intimacy and their infertility (Table 4).

Table 4.

Assessment of women’s attitude to sexual intimacy

| Question and answer options | Infertile group (n=120) |

Healthy group (n=120) |

ORa (95% CIb) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |||||

| Is sexual intimacy important? | ||||||

| Very important | 35 (30.4) | 61 (52.6) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Important | 38 (33.1) | 26 (22.4) | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) | .036 | ||

| Not important | 42 (36.5) | 29 (25.0) | 1.7 (1.1–2.9) | .040 | ||

| Are you contented with your sexual intimacy? | ||||||

| Yes, very often | 12 (10.3) | 26 (22.4) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Sometimes | 55 (47.4) | 62 (53.5) | 2.2 (1.1–4.3) | .027 | ||

| No, never | 49 (42.2) | 28 (24.1) | 3.8 (1.7–8.7) | .002 | ||

| Has your attitude to sexual intimacy changed in previous year? | ||||||

| Positively | 11 (9.5) | 29 (25.0) | 1 | Reference | ||

| Did not change | 60 (51.7) | 62 (53.4) | 2.6 (1.3–5.3) | .006 | ||

| Negatively | 45 (38.8) | 25 (21.6) | 4.8 (2.0–11.1) | <.001 | ||

aOR, Odds ratio; bCI, Confidence interval.

The second question was aimed to evaluate the role of satisfaction of sexual intimacy on infertility and was stated as ‘Are you contented with your sexual intimacy?’ Positive responses such as ‘yes, very often’ was a reference category, and ORs between that and two negative responses were 2.2 (95% CI = 1.1–4.3) and 3.8 (95% CI = 1.7–8.7), indicating their significant association with infertility (P < .05).

A significant association was found between infertility and their current feelings about sexual intimacy. Positive feelings were revealed in 9.5% of cases and 25.0% of controls. ORs of 2.6 (95% CI = 1.3–5.3) and 4.8 (95% CI = 2.0–11.1) (P < .05) fell between the reference category and two other categories with negative responses (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Although various studies have demonstrated the importance of the mind–body connection in infertility management, the psychosocial aspects of infertility in Uzbek women who are strongly bonded to their community have yet to be adequately addressed.22) In this study we tried to find as many social correlates as possible that were associated with female infertility. The social correlates of women’s infertility, such as a higher remarriage rate, inadequate family income, discontentment with daily routines, stress, poor life-quality as well as inadequate relationships with family members have not been previously reported. Hence, the association among such explanatory variables and infertility is a relatively new finding in the prospect of investigating female infertility in Uzbekistan.

In the past decade, countries in Eastern Europe and Eurasia have undergone economic and social transformations to a degree that women’s reproductive health has markedly improved along with overall health.23) Although the total fertility rate in Uzbekistan (2.8 per women) is the highest, and the rate of abortion is the lowest (0.6 per women) in central Asian countries, the infertility rate still remains high. About 15–29% of married women were reported to be abused by a spouse or partner. Such information is crucial to reaching an accurate estimate of their psychological injuries resulting from various social factors.24)

Though it is more likely that social correlates are consequences of infertility, we cannot confirm for sure that such was the case with all women, since some might have preceded infertility or even contributed to its development. Since the objective of the study was to determine the association between these factors and infertility regardless of their causal or consequential relationship with infertility, we did not concentrate on that aspect. Nevertheless, it became clear that those social correlates had a strong association with female infertility and that, according to previous studies, they seriously complicate the problem.12-17)

Bearing children is very important in Uzbek society, and most of the time it is the determining factor in the sustainability of conjugal life. It is not uncommon to find that many happy couples end up getting divorced only because of an infertility issue. However, it is also true that many couples will survive separation only because of their children. That same scenario was reflected in our study showing that the rate of remarriage was 3.5 times higher among infertile women compared with healthy women. Although uncommon, opinions contrary to our findings do exist as mentioned in the works of Schmidt (2010) who found that some infertile couples experience marital benefits, i.e., infertility brings them closer together and actually strengthens their marriages.25) Whereas that occasionally may be the case in developed countries, we still believe that in the developing world childless couples often suffer a frail conjugal bond.

A previous case-control study reported that infertile women were found to be at greater risk for sexual dysfunction, and that lower sex-life satisfaction scores often resulted in infertility-related stress.26) To determine whether sexual dysfunction was associated with infertility we focused our attention on women’s perception of the importance of sexual intimacy and how it soon changed in only one year following a diagnosis of infertility. Since in Uzbek culture women never talk openly about their attitude to sexual life, we can only clarify their attitude by asking ‘How is your attitude toward men’, since in their view ‘attitude to sexual intimacy’ is equivalent to ‘attitude to sexual life’. As study results showed, the number of women with a negative attitude towards intimacy was twice as high in the mean study group compared with healthy women, which clearly indicates its association with infertility. The same result was seen in a negative change to intimacy during that same period.

To some extent, our study can offer a contribution to knowledge about the close connection of psychosocial factors with female infertility.11, 20, 25, 26) It is well known that mental stress may cause an ovulatory dysfunction due to the inhibition of normal gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulsative secretion in the hypothalamus.19) Continuous mental suppression may cause not only anovulation but reduced fecundability i.e., the likelihood of conception depending on the pattern of sexual and pregnancy preventive behaviours.21) Thus, the treatment of infertility gets more and more difficult as infertility duration increases. Recent epidemiological studies in Uzbekistan reported that the infertility incidence in the Fergana Valley was 16.8%, with polycystic ovaries’ disease (PCOD) appearing to be the most frequent cause.27) In addition, the authors claimed that PCOD was the typical model of a metabolic syndrome which is thought to be closely related with social factors.28, 29)

The delivery of good infertility care in a community requires awareness of the implications of infertility and an insight into the context in which they occur.5) Social workers and health care professionals should be sensitive to the emotional experiences of couples during infertility treatment.21) There is a strong need for psychological and ethical counseling in the treatment of infertile couples.30, 31) An inference can be made that a positive reset of a woman’s basic relationships and attitude to her surrounding social habitat has to be an important component of the management of infertile couples. It could relieve inhibitions in the central regulation of the reproductive system and restore normal ovulation. Furthermore, a well-designed prospective study with stress-relieving intervention (travelling, physio- and psychotherapy, etc.) would contribute more in the long run to our understanding of the psychogenic aspect of infertility and its management.

Although we identified several correlates of female infertility, this study recognizes several limitations. First, it was conducted with only two small groups of cases and controls. Second, we elicited the respondents’ subjective feelings about different socioeconomic factors, which can vary depending on the personality and other factors of the respondents. Third, we conducted this study in only one hospital and only on hospitalized patients, which might have included a specific group of subjects with specific social and economic attributes. In such a case, the generalizability of the study findings may not hold up. Finally, some respondents may have developed a bias toward answering sensitive questions about their sexual intimacy and their relationships with others. A cohort study addressing all of the above limitations might better represent the actual status of the infertile women. Despite all those limitations, we consider that our findings provide helpful baseline information for future researchers as well as policy makers.

In conclusion, female infertility is strongly associated with various social correlates such as insufficient family income, poor quality of life, stress, poor relationships with family members and a lack of contentment about sexual intimacy, leading to a higher remarriage rate and further complicating the problem of infertility. Thus, correcting women’s basic attitudes and relationships to their surrounding social habitat should be an essential component of any program for infertility management.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to the staff of the Maternity Complex and Gynecology Department of the Clinics of Samarkand Medical Institute for their generous collaboration and support in the data collection. This study was supported in part by the non-profit organization ‘Epidemiological and Clinical Research Information Network (ECRIN).’

REFERENCES

- 1).Jones WR. Infertility. In: Dewhurst’s Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for Postgraduates, edited by Edmonds DK. pp. 551–561, 1999, Blackwell Publishing Professional, Oxford.

- 2).Nachtigall RD. International disparities in access to infertility services. Fertil Steril, 2006; 85: 871–875. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3).Mokhtar S, Hassan HA, Mahdy N, Elkhwsky F, Shehata G. Risk factors for primary and secondary female infertility in Alexandria: a hospital-based case-control study. JMRI, 2006; 27: 255–261.

- 4).Is infertility just a woman’s problem? New York MedicineNet, Inc.; 2012 [02 January 2012]; Available from: http://www.medicinenet.com/infertility/article.htm.

- 5).Dyer SJ, Abrahams N, Hoffman M, van der Spuy ZM. ‘Men leave me as I cannot have children’: women’s experiences with involuntary childlessness. Hum Reprod, 2002; 17: 1663–1668. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6).Gerrits T. Social and cultural aspects of infertility in Mozambique. Patient Educ Couns, 1997; 31: 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7).Okonofuaa FE, Harrisb D, Odebiyic A, Kaned T, Snowb RC. The social meaning of infertility in Southwest Nigeria. Health Transition Review, 1997; 7: 205–220.

- 8).Sami N, Ali TS. Psycho-social consequences of secondary infertility in Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc, 2006; 56: 19–22. [PubMed]

- 9).Donkor ES, Sandall J. The impact of perceived stigma and mediating social factors on infertility-related stress among women seeking infertility treatment in Southern Ghana. Soc Sci Med, 2007; 65: 1683–1694. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10).Hollos M, Larsen U. Motherhood in sub-Saharan Africa: the social consequences of infertility in an urban population in northern Tanzania. Cult Health Sex, 2008; 10: 159–173. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11).Greil AL. Infertility and psychological distress: a critical review of the literature. Soc Sci Med, 1997; 45: 1679–1704. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12).Speroff L, Fritz MA. Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility 2010, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- 13).Homan GF, Davies M, Norman R. The impact of lifestyle factors on reproductive performance in the general population and those undergoing infertility treatment: a review. Hum Reprod Update, 2007; 13: 209–223. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14).Olsen J. Cigarette smoking, tea and coffee drinking, and subfecundity. Am J Epidemiol, 1991; 133: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15).Sulovic V, Ljubic A. Medical and social factors affecting reproduction in Serbia. Srp Arh Celok Lek, 2002; 130: 247–250. [PubMed]

- 16).Terava AN, Gissler M, Hemminki E, Luoto R. Infertility and the use of infertility treatments in Finland: prevalence and socio-demographic determinants 1992–2004. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol, 2008; 136: 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17).Tolstrup JS, Kjaer SK, Holst C, Sharif H, Munk C, Osler M, Schmidt L, Andersen AM, Gronbaek M. Alcohol use as predictor for infertility in a representative population of Danish women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2003; 82: 744–749. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18).Ombelet W, Campo R. Affordable IVF for developing countries. Reprod Biomed Online, 2007; 15: 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19).Buck GM, Sever LE, Batt RE, Mendola P. Life-style factors and female infertility. Epidemiology, 1997; 8: 435–441. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20).Chachamovich JR, Chachamovich E, Ezer H, Fleck MP, Knauth D, Passos EP. Investigating quality of life and health-related quality of life in infertility: a systematic review. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol, 2010; 31: 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21).Schneider MG, Forthofer MS. Associations of psychosocial factors with the stress of infertility treatment. Health Soc Work, 2005; 30: 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22).Kamaev IA, Petrushenkova ON. Risk factors of the primary and secondary female sterility. Probl Sotsialnoi Gig Zdravookhranenniiai Istor Med, 2003: 19–21. [PubMed]

- 23).Ashford L. Reproductive health trends in Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Washington, DC 20009 USA: Population Reference Bureau 2003 [cited 2012 15 April 2012]; Available from: http://www.prb.org/pdf/ReproductiveHealthTrendsEE.pdf.

- 24).Haub C. World Population Data Sheet - World Development Indicators 2000; and official government estimates for fertility: World Bank 2002.

- 25).Schmidt L. Psychosocial Consequences of Infertility and Treatment In: Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Integrating Modern Clinical and Laboratory Practice, edited by DT Carrell, CM Peterson. pp. 93–100, 2010, Springer Science and Business Media.

- 26).Millheiser LS, Helmer AE, Quintero RB, Westphal LM, Milki AA, Lathi RB. Is infertility a risk factor for female sexual dysfunction? A case-control study. Fertil Steril, 2010; 94: 2022–2025. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27).Khaidarova FA. Medico-biologic aspects of infertile marriage in the region of Fergana valley. Problemi biologii i medicini, 2007; 1: 119–122.

- 28).Ismailov SI, Khaidarova FA. The clinical and epidemiological aspects of endocrine infertility. Nazariy va klinik tibbiyot jurnali (Uzb), 2009; 5: 86–88.

- 29).Khaidarova FA. Waist circumference as a marker of metabolic disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and normal body mass. Mejdunarod Endocrinol J, 2009; 6: 90–97.

- 30).Sina M, Ter Meulen R, Carrasco de Paula I. Human infertility: is medical treatment enough? a cross-sectional study of a sample of Italian couples. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol, 2010; 31: 158–167. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31).Wiersema NJ, Drukker AJ, Mai BT, Giang HN, Nguyen TN, Lambalk CB. Consequences of infertility in developing countries: results of a questionnaire and interview survey in the South of Vietnam. J Transl Med, 2006; 4: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]