ABSTRACT

A 47-year-old female had noticed diminished visual acuity in both eyes 2 months previously. The patient had vision loss (no light perception) in her right eye on admission. Her left visual acuity was 1.2 (naked vision) and an upper temporal quadrant hemianopsia was revealed in her left eye. Optic disc atrophy was also found bilaterally during a fundus examination. The tumor was located at the tuberculum sella.

The first operation was performed using a right pterional approach. The right optic nerve was thin and atrophic and was severely encased by the tumor. Considering the deterioration of her visual evoked potential, the operation was terminated in the remaining major part of the tumor. Postoperatively, the patient suffered visual loss in her right eye (no light perception), decreased visual acuity (naked: 0.6 (corrected: 1.0)), and deteriorated visual field defects (upper temporal quadrant hemianopsia) in her left eye.

The tumor remnant was resected again 2 weeks later using the right frontobasal and pterional approaches. The tumor around the bilateral internal carotid arteries and optic nerves was not resected. Light perception in the right eye appeared 2 weeks after the operation. Although an opthalmological examination revealed right optic atrophy, finger counting was possible in the upper nasal visual field of the right eye three months after the second operation. Her visual acuity was 0.7 (1.0), and the upper temporal quadrant hemianopia of the left eye improved in comparison with the preoperative one. Our case demonstrated the possibility of a recovery from blindness.

Key Words: Postoperatine recovery, Blindness, Tuberculum sella, Meningioma, Visual evoked potential

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculum sellae meningiomas present a special challenge because of their close proximity to anterior visual pathways. We experienced a case whose right visual acuity recovered from blindness after surgery of a tuberculum sellae meningioma. Here we report our case with some discussion.

CASE REPORT

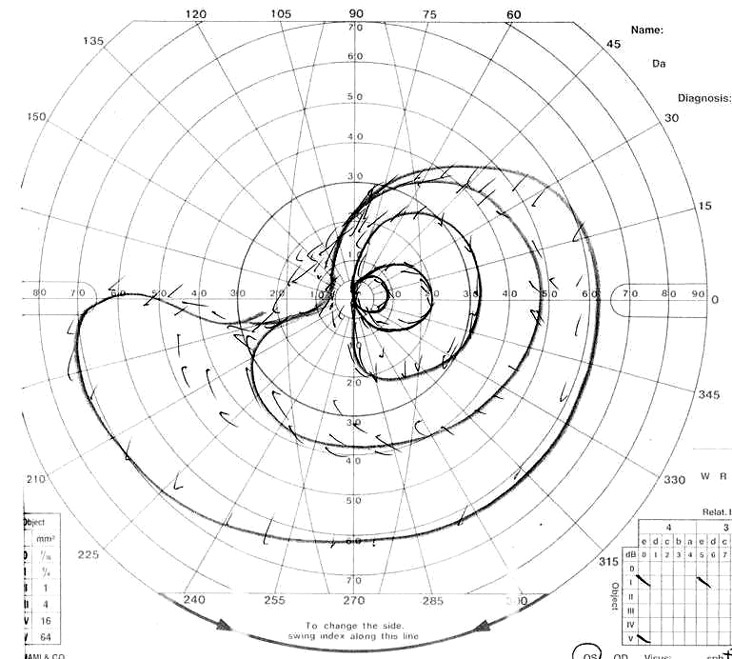

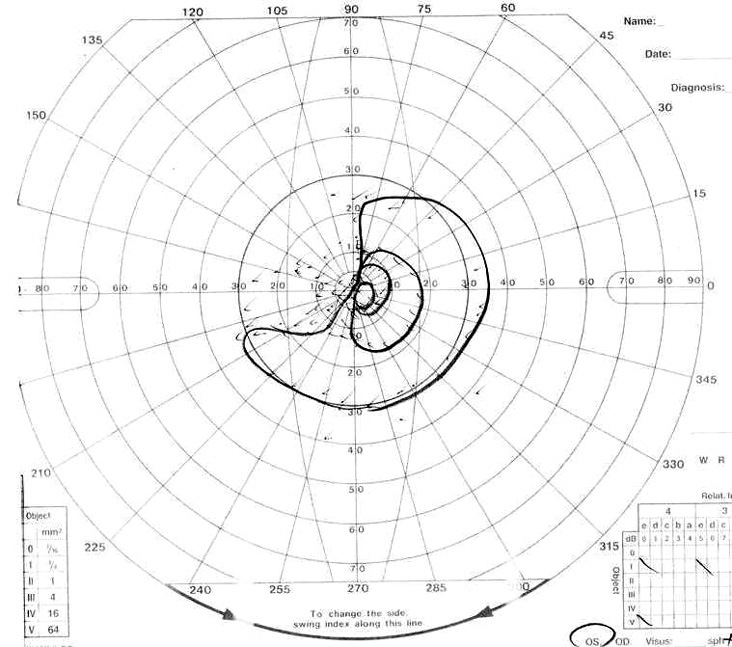

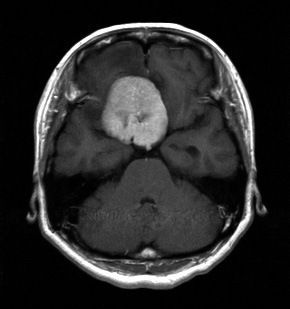

A 47-year-old female had suffered from drop attacks following the paresis of her bilateral lower extremities 18 months previously. The patient had noticed diminished visual acuity in both eyes 2 months before. She presented with vision loss (no light perception) in her right eye on admission. Her left visual acuity was 1.2 (naked vision) and an upper temporal quadrant hemianopsia was revealed in her left (Fig. 1A). Optic disc atrophy was also discovered bilaterally during a fundus examination. Flash visual-evoked potentials could be clearly recorded through a simple flash stimulus of the left eye. However, the visual-evoked potential from the right eye showed no measurable response. The tumor was located at the tuberculum sella and was attached to the right side of the planum sphenoidale and diaphragma sellae dura by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

Visual field

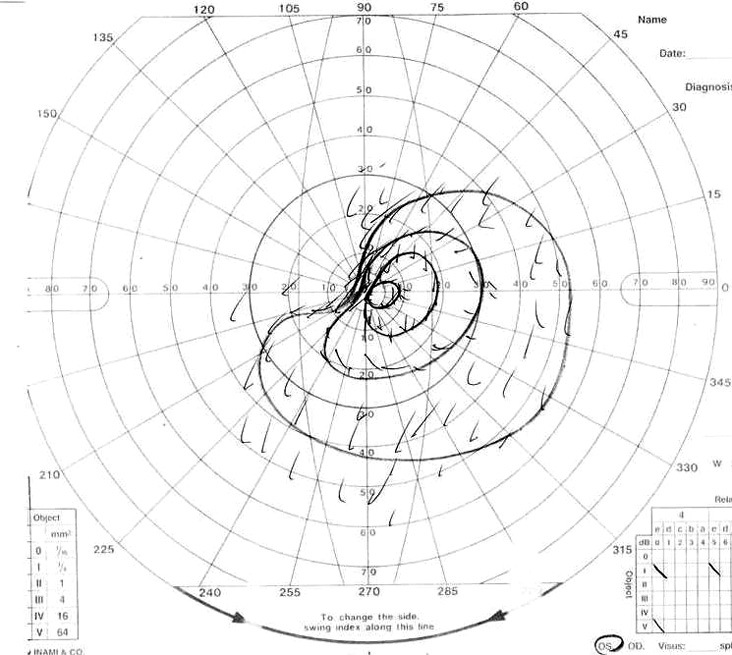

Fig. 1A.

Visual field of left eye on admission. Patient showed upper lateral quadrant hemianopsia.

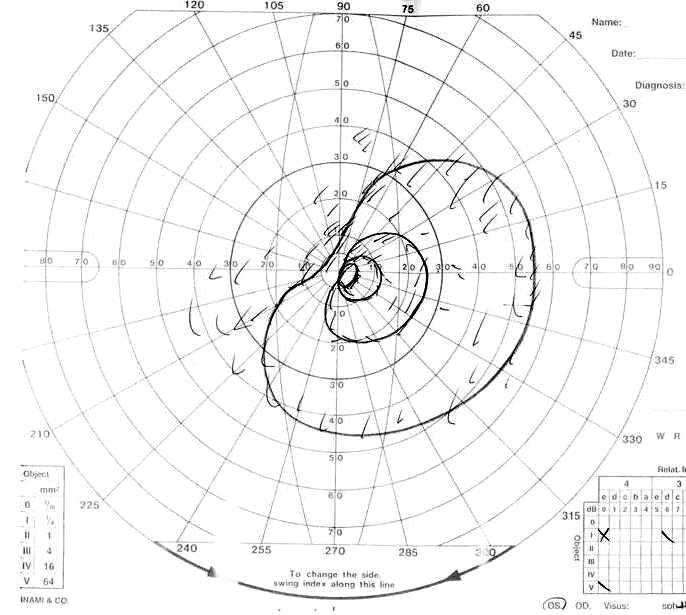

Fig. 1B.

Visual field of left eye 3 days after first operation.

Fig. 1C.

Visual field of left eye 10 days after first operation.

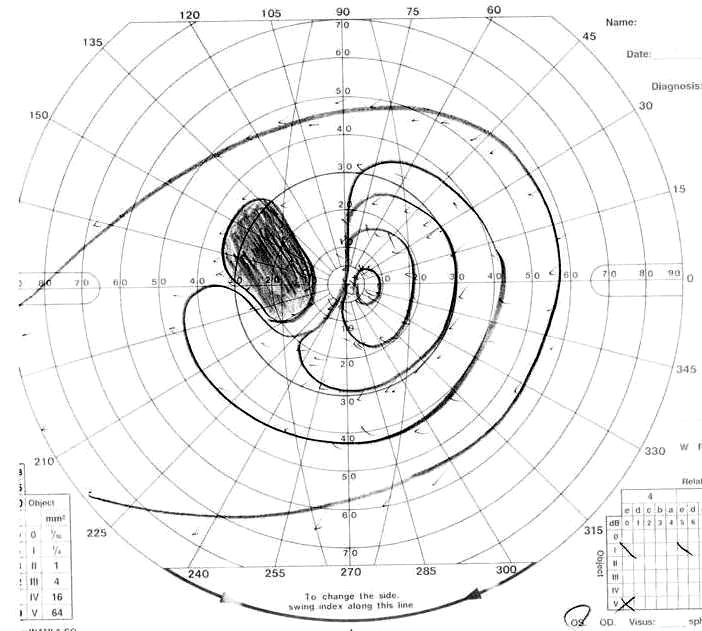

Fig. 1D.

Visual field of left eye 7 days after second operation.

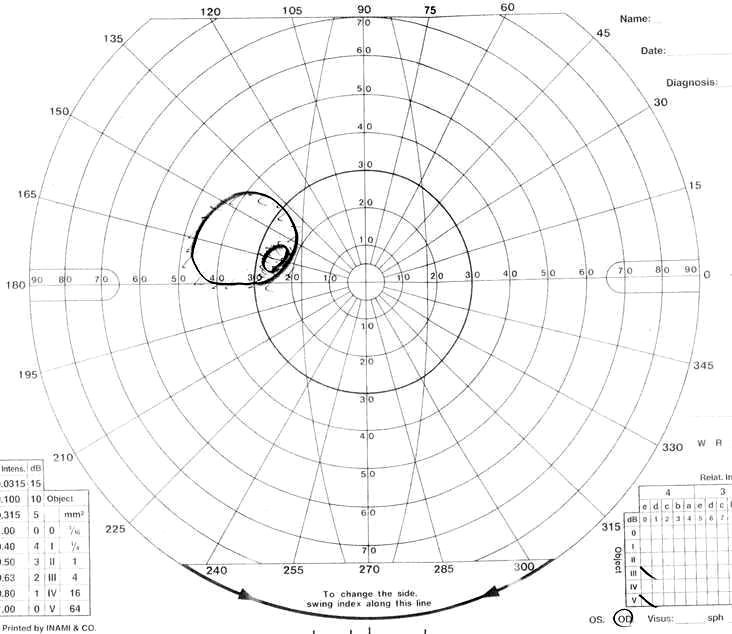

Fig. 1F.

Visual field of right eye 3 months after second operation.

Fig. 1E.

Visual field of left eye 3 months after second operation.

Fig. 2.

Gd-DTPA enhanced MRI, axial view

Fig. 2A.

MRI on admission. Tumor was located at the tuberculum sellae.

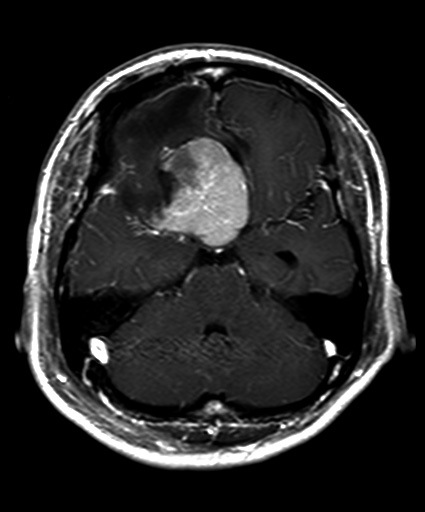

Fig. 2B.

MRI after first operation. Tumor was only partially resected.

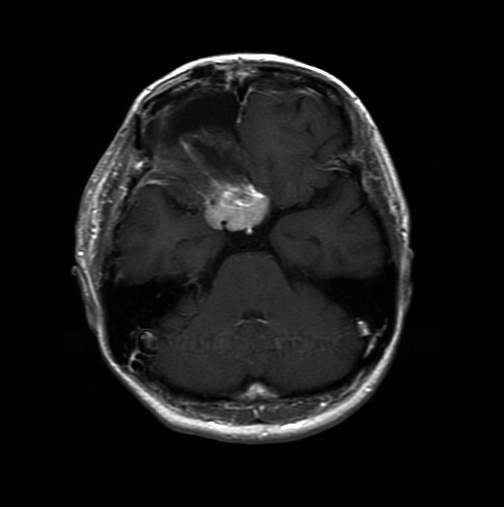

Fig. 2C.

MRI after second operation. Tumor was diminished remarkably compared to preoperative size.

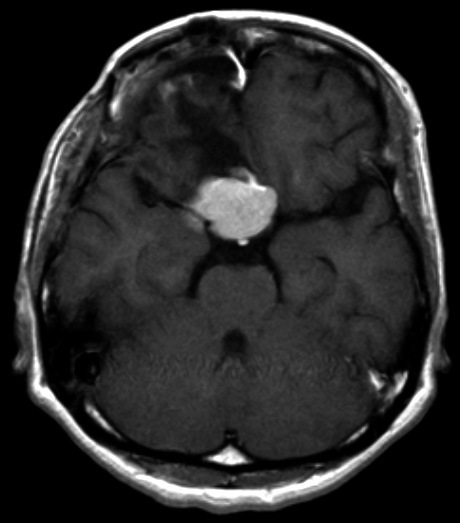

Fig. 2D.

MRI 25 months after second operation. Some enlargement of tumor was seen in comparison with size after second operation.

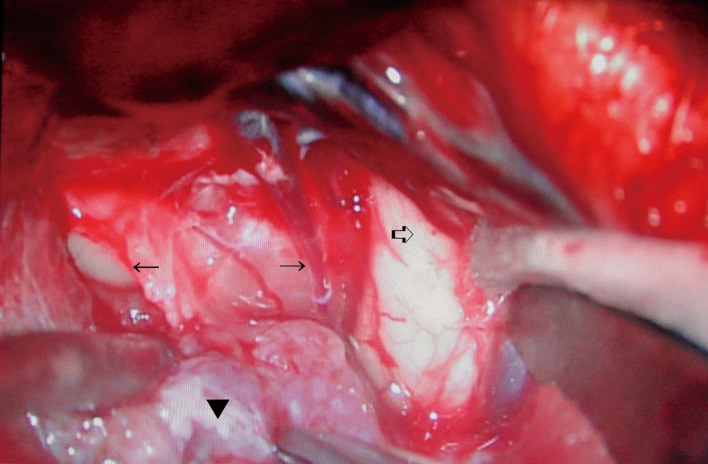

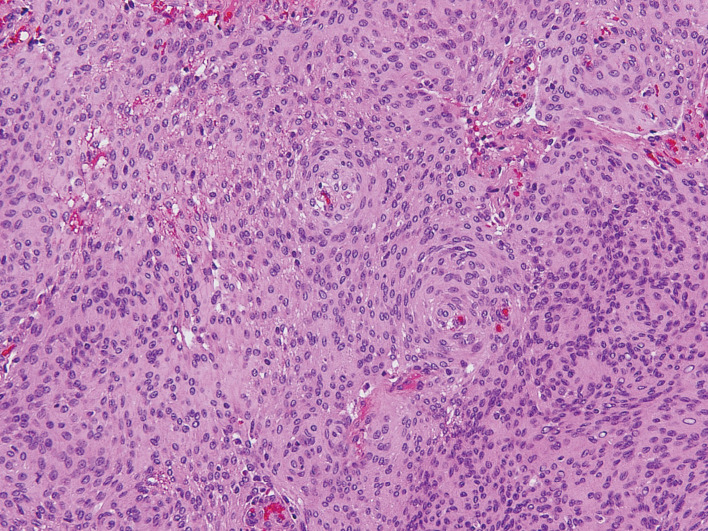

The operation was performed via a right pterional approach to minimize the intraoperative damage to the left optic nerve. General anesthesia was administered using nitrous oxide and 100 mg/hour of propofol. The right optic nerve was thin and atrophic and was severely encased by the tumor which showed a moderate hardness (Fig. 3). Intraoperative flash visual-evoked potentials recorded from the left eye readily disappeared during the internal decompression of the tumor. While the visual-evoked potentials returned to the preoperative pattern soon after the interruption of manipulation, the operation was continued. However, those potentials finally disappeared completely, so that the operation was terminated in the remaining major part of the tumor (Fig. 2B). A histological examination revealed sheet-like and/or whorl formations of elongated and crescent-shaped cells with oval nuclei (Fig. 4). The tumor proved positive for epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin, but negative for S-100 protein. The pathology was a meningothelial meningioma with an MIB-1 index of 2%.

Fig. 3.

Operative microscopic view of first operation. Right pterional approach.

Tumor (▼) encased right optic nerve (← →), which was thin and atrophic. White arrow (⇒) showed right temporal lobe.

Fig. 4.

Histological examination of first operation. Hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×200.

The examination revealed sheet-like and/or whorl formations of elongated and crescent-shaped cells with oval nuclei. Pathology was meningothelial meningioma.

Postoperative ophthalmological examinations showed a worsening of her visual symptoms in her left eye. The patient had suffered visual loss in her right eye (no light perception), decreased visual acuity (naked: 0.6 (corrected: 1.0)), and visual field defects (upper temporal quadrant hemianopsia) in her left eye (Fig. 1B, C). Although the visual field defects of her left eye had markedly deteriorated 3 days after the operation, it was somewhat improved 9 days later.

The tumor remnant was resected again 2 weeks later, using right frontobasal and pterional approaches combined. General anesthesia was administered using nitrous oxide and 80 mg/hour of propofol. The tumor forciblycompressed her bilateral optic nerves from the medial side, while her optic nerves were stretched laterally. Intraoperative monitoring with flash visual-evoked potentials was recorded from the left eye. Although those potentials disappeared during the removal of the meningioma, the operation was continued on this occasion. The bilateral carotid arteries were encased within the tumor; although the tumor around those arteries and optic nerves was not resected, the tumor could be diminished remarkably compared to its preoperative size (Fig. 2C). A histological examination showed no obvious change except for several areas of fibrinoid necrosis due to the first operation.

One week after the second operation, her right vision was blind (no light perception) and she had slightly decreased visual acuity (0.5 (1.0)). A visual field defect of the left eye did not change (Fig. 1D). However, light perception in the right eye returned 2 weeks after the operation. The visual-evoked potentials of her left eye showed the preoperative pattern 2 months after the second operation, although the corresponding potentials of her right eye showed no measurable response. Though an opthalmological examination revealed right optic atrophy, finger counting was possible in the upper nasal visual field of her right eye three months after the second operation (Fig. 1F). Her visual acuity was 0.7 (1.0), and the upper temporal quadrant hemianopia of the left eye improved in comparison with the preoperative level (Fig. 1E).

The tumor tended to increase 7 months after the second operation. The tumor has currently increased to some extent, but her visual acuity is 0.8 (1.0) in the left eye and finger counting in the right eye is possible 25 months after the second operation (Fig. 2D). The visual field shows no obvious change.

DISCUSSION

Recovery from blindness is very rare after the removal of tuberculum sellae meningioma, and only one such case was found in Silva’s report.1) Our case presents a second report of a recovery from blindness. As for the preoperative blind and/or non-blind cases of the tuberculum sellae meningioma, several reports have mentioned that vision had improved in 44.4–79%, remained stable in 17–40% and deteriorated in 4–25%.2-7) Visual outcomes were mainly affected by age, preoperative visual impairment, duration of symptoms, tumor size and consistency, and especially in a situation involving the optic nerve, in which compression of the tumor itself and adherence to the surrounding tissues occurred.3) Visual prognosis was favorably affected by any age under 54.7,8) A mild preoperative loss of visual acuity (> 0.02) also appeared to be a favorable prognostic factor.4,7) The patients with a symptom duration of less than 7–12 months showed a greater likelihood of visual improvement.6-10) In our case, the preoperative right visual acuity was poor, but the patient was young, and the duration of her preoperative visual disturbance was relatively short. These effects might indicate a favorable outcome. The operative findings also showed a relation to the outcome. Patients with a soft tumor had a greater likelihood of visual improvement than those with a hard tumor.6) The intraoperative findings predicting an unfavorable visual outcome were a thin atrophic optic nerve, encasement of the optic nerve, or a tumor adhesion to its undersurface.2) In our case, the right optic nerve was atrophic and was encased within the tumor. The adhesion between the optic nerve and the tumor was prominent, but the tumor consistency was relatively soft. This factor seemed to also have some relationship with a good outcome.

The operative method is the major factor affecting the visual outcome. An improvement in visual acuity was reported to be significantly better in the extended transsphenoidal surgery group than in the transcranial surgery group.11) However, we did not use the extended transsphenoidal approach for fear of postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage. The frontobasal interhemispheric approach can also minimize the intraoperative damage to the optic chiasm.12) In the second operation, we avoided the interhemispheric approach, since the right frontobasal approach with a craniotomy just medial to the midline provided easier access to the medial part of the tumor. Great care should be taken to preserve the feeding arteries of optic nerves during dissection. We avoided removing the tumor around the optic nerves to preserve the microvasculature supplying the optic apparatus.2) That factor also seemed to have some relationship with a good outcome.

In our case, flash visual-evoked potentials were recorded before, during and after the operation. Those potentials showed a clear correlation with the deteriorated visual symptoms. Silva has indicated that 2 cases showed no visual-evoked potentials in spite of the partially-impaired visual acuity, while 3 cases evidenced a delay in the latency of visual-evoked potentials in spite of intact visual acuity and visual field.1) As shown above, visual-evoked potentials are considered a highly sensitive means of identifying the condition of the optic pathway. However, the intraoperative visual-evoked potentials were too sensitive to risk an intraoperative decision. Intraoperative visual-evoked potentials can be influenced not only by the surgical manipulation of the optic nerve and/or chiasm but also by anesthetic agents such as halothane. Those potentials disappear under the inhalation of 2% halothane.1) Although we used propofol for anesthesia, its amplitude was diminished even before the surgical manipulation. In our case, both the visual acuity and visual field recovered postoperatively, although the intraoperative visual-evoked potentials disappeared completely. Silva has also reported that intraoperative visual-evoked potentials became flattened under the manipulation of the optic nerve, but soon recovered after an interruption of the manipulation in the case of two-thirds and within the operation period in another one-third.1) In view of both our case and Silva’s report, the intraoperative visual-evoked potential seemed to play only a supplementary role at this stage.

REFERENCES

- 1).Silva ICE, Wang AD, Symon L. The application of flash visual evoked potentials during operations on the anterior visual pathways. Neurol Res, 1985; 7: 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2).Bassiouni H, Asgari S, Stolke D. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: functional outcome in a consecutive series treated microsurgically. Surg Neurol, 2006; 66: 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3).Galal A, Faisal A, Al-Werdany M, El Shehaby A, Lotfy T, Moharram H. Determinants of postoperative visual recovery in suprasellar meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2010; 152: 69–77. Epub 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4).Ganna A, Dehdashti AR, Karabatsou K, Gentili F. Fronto-basal interhemispheric approach for tuberculum sellae meningiomas; long-term visual outcome. Br J Neurosurg, 2009; 23: 422–430. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5).Jallo GI, Benjamin V. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: microsurgical anatomy and surgical technique. Neurosurgery, 2002; 51: 1432–1440. [PubMed]

- 6).Kim TW, Jung S, Jung TY, Kim IY, Kang SS, Kim SH. Prognostic factors of postoperative visual outcomes in tuberculum sellae meningioma. Br J Neurosurg, 2008; 22: 231–234. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7).Zevgaridis D, Medele RJ, Müller A, Hischa AC, Steiger HJ. Meningiomas of the sellar region presenting with visual impairment: impact of various prognostic factors on surgical outcome in 62 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2001; 143: 471–476. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8).Schick U, Hassler W. Surgical management of tuberculum sellae meningiomas: involvement of the optic canal and visual outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2005; 76: 977–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9).Grisoli F, Diaz-Vasquez P, Riss M, Vincentelli F, Leclercq TA, Hassoun J, Salamon G. Microsurgical management of tuberculum sellae meningiomas. Results in 28 consecutive cases. Surg Neurol, 1986; 26: 37–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10).Nakamura M, Roser F, Struck M, Vorkapic P, Samii M. Tuberculum sellae meningiomas: clinical outcome considering different surgical approaches. Neurosurgery, 2006; 59: 1019–1029. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11). Kitano M, Taneda M, Nakao Y. Postoperative improvement in visual function in patients with tuberculum sellae meningiomas: results of the extended transsphenoidal and transcranial approaches. J Neurosurg, 2007; 107: 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12). Uede T, Ohtaki M, Nonaka T, Tanabe S, Hashi K. Characteristics of visual impairment complicated with planum sphenoidale and tuberculum sellae meningiomas and their surgical results. No Shinkei Geka, 1996 (in Japanese); 24: 1093–1098. [PubMed]