Abstract

Background and Purpose

Presynaptic, release‐regulating metabotropic glutamate 2 and 3 (mGlu2/3) autoreceptors exist in the CNS. They represent suitable targets for therapeutic approaches to central diseases that are typified by hyperglutamatergicity. The availability of specific ligands able to differentiate between mGlu2 and mGlu3 subunits allows us to further characterize these autoreceptors. In this study we investigated the pharmacological profile of mGlu2/3 receptors in selected CNS regions and evaluated their functions in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE).

Experimental Approach

The comparative analysis of presynaptic mGlu2/3 autoreceptors was performed by determining the effect of selective mGlu2/3 receptor agonist(s) and antagonist(s) on the release of [3H]‐d‐aspartate from cortical and spinal cord synaptosomes in superfusion. In EAE mice, mGlu2/3 autoreceptor‐mediated release functions were investigated and effects of in vivo LY379268 administration on impaired glutamate release examined ex vivo.

Key Results

Western blot analysis and confocal microscopy confirmed the presence of presynaptic mGlu2/3 receptor proteins. Cortical synaptosomes possessed LY541850‐sensitive, NAAG‐insensitive autoreceptors having low affinity for LY379268, while LY541850‐insensitive, NAAG‐sensitive autoreceptors with high affinity for LY379268 existed in spinal cord terminals. In EAE mice, mGlu2/3 autoreceptors completely lost their inhibitory activity in cortical, but not in spinal cord synaptosomes. In vivo LY379268 administration restored the glutamate exocytosis capability in spinal cord but not in cortical terminals in EAE mice.

Conclusions and Implications

We propose the existence of mGlu2‐preferring and mGlu3‐preferring autoreceptors in mouse cortex and spinal cord respectively. The mGlu3‐preferring autoreceptors could represent a target for new pharmacological approaches for treating demyelinating diseases.

Abbreviations

- [3H]‐d‐Asp

[3H]‐d‐aspartate

- d.p.i.

days post‐immunization

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- LY341495

(2S)‐2‐amino‐2‐[(1S,2S)‐2‐carboxycycloprop‐1‐yl]‐3‐(xanth‐9‐yl) propanoic acid

- LY379268

(1R,4R,5S,6R)‐4‐amino‐2‐oxabicyclo[3.1.0]‐hexane‐4,6‐dicarboxylic acid

- LY541850

(1S,2S,4R,5R,6S)‐2‐amino‐4‐methylbicyclo[3.1.0]‐hexane2,6‐dicarboxylic acid

- mGlu2/3

metabotropic glutamate 2 and 3

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NAAG

N‐acetyl‐aspartyl‐glutamate

- Stx‐1A

syntaxin‐1A

- VGLUT

vesicular transporter of glutamate

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| GPCRs a | Transporters b |

| mGlu2 receptor | VGLUT1 |

| mGlu3 receptor |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 (a,bAlexander et al., 2015a, 2015b).

Introduction

Metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) 2 and 3 (mGlu2/3) receptor subtypes belong to the second group of mGlu receptors and are coupled to G1/G0 proteins in heterologous expression system. They preferentially inhibit cAMP and cGMP production and voltage‐sensitive Ca2 + channels (Pin and Duvoisin, 1995; Bockaert et al., 2002; Wrobleska et al., 2006; Nicoletti et al., 2011). mGlu2/3 are widely expressed in neurones at the presynaptic level (Luján et al., 1997; Tamaru et al., 2001), where they control neurotransmitter release (Cartmell and Schoepp, 2000; Niswender and Conn, 2010). They exist in glutamatergic nerve endings, in different CNS regions, including the cortex and spinal cord, where they are preferentially located in the preterminal regions of the axon, and can therefore be activated by synaptic glutamate as well as by glutamate released by neighbouring astrocytes via the cysteine/glutamate antiporter (Kalivas, 2009).

mGlu2/3 receptors are characterized by a high sequence homology that restricts the possibility of distinguishing the two receptor subtypes from a pharmacological point of view. However, only recently, it was definitively shown that N‐acetyl‐aspartyl‐glutamate (NAAG) selectively binds to the mGlu3 receptor subtype (Neale, 2011; Olszewski et al., 2012) and that the new compound LY541850 acts as a selective mGlu2 receptor agonist with mGlu3 receptor antagonist activity. The pharmacological profile of the latter drug was first proposed on the basis of results obtained in human mGlu receptors in cultured neurons (Sanger et al., 2013) and then confirmed in electrophysiological studies (Hanna et al., 2013). Thus, NAAG and LY541850 represent unique pharmacological tools so far available to predict the subunit composition of mGlu2/mGlu3 receptors. The ability to discriminate the different mGlu2/3 receptor subtypes is of even more of interest, because mGlu2/3 receptor agonists have been proposed to be suitable candidates for treating diseases typified by central hyperglutamatergicity, including demyelinating disorders. In fact, previous studies have shown that drugs, which favour NAAG bioavailability in the CNS can ameliorate the symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS) (Rahn et al., 2012).

Glutamate exocytosis is largely altered in the cortex and spinal cord of mice suffering from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a demyelinating disorder that shares some histological features with human MS (Di Prisco et al., 2013). In particular, the exocytosis of glutamate was reduced in the cortex but potentiated in the spinal cord of EAE at the acute stage of disease (i.e. 21 days post‐immunization, d.p.i.). We determined whether activation of presynaptic mGlu2/3 autoreceptors could restore glutamate exocytosis to physiological levels. With this aim, we firstly characterized the pharmacological profile of the mGlu2/3 autoreceptors expressed in glutamate terminals of the cortex and spinal cord of control, non‐immunized mice. Then we investigated whether mGlu2/3 autoreceptor‐mediated functions are altered in nerve endings isolated from EAE mouse cortical and spinal cord synaptosomes. Finally, the effect of in vivo administration of LY379268 on glutamate alterations in these CNS regions of EAE mice at 21 d.p.i was studied.

Our results suggest the existence of a presynaptic NAAG‐sensitive mGlu3‐preferring autoreceptor in spinal cord glutamate nerve endings and of a presynaptic LY541850‐sensitive mGlu2‐preferring autoreceptor in cortical terminals. An agonist of spinal cord mGlu3‐preferring receptors was found to have beneficial effects on the synaptic defects that occur in EAE mice at 21 d.p.i.

Methods

Animals and induction of EAE

Animal studies are reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath and Lilley, 2015). Mice (female and male, strain C57BL/6J) were obtained from Charles River (Calco, Italy) and were housed in the animal facility of DIFAR, Section of Pharmacology and Toxicology (authorization n° 484 of 8 June 2004). The experimental procedures were in accordance with the European legislation (European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986, 86/609/EEC), and they were approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (DDL 26/2014 and previous legislation; protocol number n° 50/2011‐B). Experiments were performed following the Guidelines for Animal Care and Use of the National Institutes of Health.

To induce EAE, female mice (C57BL/6J; 18–20 g, 6–8 weeks‐old) were immunized according to a standard protocol (Zappia et al., 2005), with minor modifications. Briefly, animals were s.c. injected with incomplete Freund's adjuvant containing 4 mg·mL−1 Mycobacterium tuberculosis (strain H37Ra) and 400 μg of the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein 35–55 (MOG35–55) peptide, followed by i.p. administration of 250 ng of pertussis toxin on day 0 and after 48 h. Clinical scores (0 = healthy, 1 = limp tail, 2 = ataxia and/or paresis of hindlimbs, 3 = paralysis of hindlimbs and/or paresis of forelimbs, 4 = tetraparesis and 5 = moribund or death) were recorded daily [MOG33–55 (+)]. EAE mice were killed at 21 ± 1 d.p.i. Control, non‐immunized mice received the same treatment in the absence of the MOG35–55 peptide [MOG33–55 (−) mice]. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to use the minimum number of animals necessary to produce reliable results.

Fifty‐two C57BL/6 mice were used to carry out the experiments aimed at investigating the existence and functional role(s) of presynaptic mGlu2/3 autoreceptors in the cortex and the spinal cord. Eight female C57BL/6 mice (4 MOG33–55 (−) mice and MOG33–55 (+) mice at 21 ± 1 d.p.i. were used for the experiments carried out to evaluate the effect of LY379268 in in vitro studies. Thirty‐six female C57BL/6 mice (12 mice for each set of experiments, three different sets, 18 mice [4 MOG33–55 (−) mice and 18 MOG33–55 (+) mice at 21 ± 1 d.p.i.)] were used for the experiments carried out to evaluate the effect of LY379268 in ex vivo, in vitro studies.

Animal drug treatments

Female C57BL/6 mice (12 mice for each set of experiments, three different sets) were randomly assigned to the following groups: control mice, EAE mice, LY379268‐treated control mice and LY379268‐treated EAE mice. Animals were administered LY379268 (0.01 to 1 mg·kg−1) i.p. 3 h before being killed (Di Prisco et al., 2014a).

Preparation of synaptosomes

The animals were killed by decapitation, the cortices and the spinal cord rapidly removed and purified synaptosomes prepared within minutes (Musante et al., 2011). Briefly, control 13 d.p.i., EAE mice were killed by decapitation, the cortices rapidly removed and purified isolated nerve endings (synaptosomes) prepared within minutes. Synaptosomes were resuspended in a physiological solution with the following composition (mM): NaCl, 140; KCl, 3; MgSO4, 1.2; CaCl2, 1.2; NaH2PO4, 1.2; NaHCO3, 5; HEPES, 10; glucose, 10; pH, 7.2–7.4.

Experiments of release

Synaptosomes were incubated for 15 min at 37°C in a rotary water bath in the presence of [3H]‐d‐aspartate ([3H]‐d‐Asp, f.c.: 50 nM). Identical amounts of the synaptosomal suspensions were layered on microporous filters at the bottom of parallel thermostated chambers in a superfusion system (Raiteri et al., 1974; Ugo Basile, Comerio, Varese, Italy; Summa et al., 2013).

Synaptosomes were transiently (90 s) exposed, at t = 39 min, to high‐KCl‐containing medium (12 or 15 mM, as indicated, NaCl was reduced in an equimolar concentration for the increase of KCl) in the absence or presence of agonists. Antagonists were added 8 min before agonists. Fractions were collected as follows: two 3‐min fractions (basal release), one before (t = 36–39 min) and one after (t = 45–48 min) a 6‐min fraction (t = 39–45 min; evoked release). Fractions collected and superfused synaptosomes were measured for radioactivity.

The amount of radioactivity released into each superfusate fraction was expressed as percentage of the total radioactivity. The K+‐induced overflow was estimated by subtracting the neurotransmitter content into the first and third fractions collected (basal release, b1 and b3) from that in the 6‐min fraction collected during and after the depolarization pulse (evoked release, b2). In order to compare the results of the experiments aimed at describing the pharmacological profile of the receptors under study, the effect of agonists/antagonists is expressed as a percentage of the KCl‐evoked overflow of tritium observed in the absence of mGlu2/3 ligands. Each experimental condition was tested in three parallel superfusion chambers within the same experiment in order to evaluate the variability and accuracy of the measurement, that is, the repeatability. For each experiment, data are expressed as media of the three determinations. The [3H]‐d‐Asp release from cortical synaptosomes in the (b1 + b3) fractions amounted to 0.94 ± 0.03% of the total synaptosomal radioactivity; that elicited by 12 mM KCl (b2) corresponded to 2.18 ± 0.07% of the total synaptosomal radioactivity (data are means ± SEM of five representatives run on different days). The [3H]‐d‐Asp release in the (b1 + b3) fractions from spinal cord synaptosomes amounted to 2.89 ± 0.11% of the total synaptosomal radioactivity; that elicited by 15 mM KCl (b2) corresponded to 4.23 ± 0.31% of the total synaptosomal radioactivity (data are means ± SEM of five representatives run on different days).

Immunoblotting

Synaptosomes obtained from the cortex or spinal cord were lysed in ice‐cold lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris, 1% Triton X‐100, protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 8.0) and quantified for protein content. Samples were boiled for 5 min at 95°C in SDS‐PAGE loading buffer and then separated by SDS‐10% PAGE (cortical lysate: 5–10 μg per lane; spinal cord lysate: 10–20 μg per lane) and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature in Tris‐buffered saline‐Tween (0.02 M Tris, 0.150 M NaCl, and 0.05% Tween 20, 5% non‐fat dried milk) and then probed with rabbit anti‐mGlu2/3 (1:4000; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) and mouse anti‐β tubulin III (1:800, Sigma, Milano, Italy), overnight at 4°C. After extensive washes in Tris‐buffered saline‐Tween, membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with appropriate HRP‐linked secondary antibodies (1:20000). Immunoblots were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence plus Western blot detection system.

Immunocytochemical analysis in mouse cortical and spinal nerve terminals

For immunohistochemical analysis, cortical and spinal synaptosomes were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X‐100 PBS for 5 min and incubated with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti‐mGlu2/3 receptor (1:1000; Novus Biologicals); mouse anti‐syntaxin‐1A (Stx‐1A; 1:10,000; GeneTex Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) and guinea pig anti‐vesicular transporter of glutamate type 1 (VGLUT‐1; 1:500; Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). After extensive washing, synaptosomes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with AlexaFluor‐488 or 633 donkey anti‐mouse IgG antibodies, AlexaFluor‐488 or 633 donkey anti‐rabbit IgG antibodies or AlexaFluor‐488 donkey anti‐guinea pig IgG antibodies (1:1000 for all; Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Synaptosomes were then applied onto coverslips (Musante et al., 2008a).

Confocal microscopy and colocalization

Fluorescent images were acquired and examined using a six‐channel Leica (Leica Microsystem SrL, Milano, Italy) TCS SP5 laser‐scanning confocal microscope, equipped with 458, 476, 488, 514, 543 and 633 nm excitation lines and a two‐photon pulsed Ti‐sapphire laser. Images (1024 × 1024 × 12 bit) were taken through a plan‐apochromatic oil immersion objective 63×/NA1.4. Light collection configuration was optimized according to the combination of chosen fluorochromes, and sequential channel acquisition was performed to avoid crosstalk phenomena. Leica LCS software package was used for acquisition, storage and visualization. The quantitative estimation of colocalized proteins was performed as described previously (Musante et al., 2008a; Summa et al., 2013).

Data and statistical analysis

The data and statistical analysis comply with the recommendations on experimental design and analysis in pharmacology (Curtis et al., 2015). ANOVA was performed by anova followed by Dunnett's test or Newman–Keuls multiple comparisons test, as appropriate; direct comparisons were performed by Student's t‐test. Post hoc tests were carried out only if the F value was significant. Data were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Chemicals

[2,3‐3H]‐d‐aspartate (specific activity 11.3 Ci·mmol−1) was from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA, USA). The Freund's incomplete adjuvant was acquired from Sigma‐Aldrich (Milan, Italy) and MOG from Espikem (Florence, Italy). M. tuberculosis (H37Ra) was obtained from DIFCO BACTO Microbiology (Lawrence, KA, USA). LY379268, LY341495 and spaglumic acid (NAAG) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (purity level 96%; Bristol, UK). LY541850 was kindly provided by Dr Moon (Ely Lilly, Indianapolis, USA).

The drug and molecular target nomenclature conforms to British Journal of Pharmacology's Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2011).

Results

Presynaptic mGlu2/3 autoreceptors in mouse cortical glutamatergic nerve endings

Purified nerve endings isolated from mouse cortex were preloaded with [3H]‐d‐Asp (a nonmetabolizable glutamate analogue routinely used in release studies as a marker of the endogenous excitatory amino acid transmitter; Grilli et al., 2004; Luccini et al., 2007) and transiently exposed to a mild (12 mM KCl) depolarizing stimulus in the absence or presence of the mGlu2/3 agonist LY379268. Well in line with previous observations (Cartmell and Schoepp, 2000; Niswender and Conn, 2010), the activation of presynaptic mGlu2/3 autoreceptors inhibited efficiently the 12 mM K+‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow. Maximal inhibition (−44 ± 7.1%, n = 5) was observed when the agonist was added at 10 nM, and it was not modified when higher concentrations of the agonist were applied (Figure 1A). The apparent EC50 of the agonist amounted to 1.50 ± 1.15 nM. The 10 nM LY379268‐mediated inhibitory effect was prevented when the mGlu2/3 antagonist LY341495 (100 nM) was concomitantly added (Figure 1B). At the concentration applied, the mGlu2/3 antagonist failed to modify on its own the 12 mM KCl‐evoked release of tritium (data not shown). To note, the 12 mM K+‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp release occurred in a Ca2 +‐dependent, exocytotic‐like manner as already demonstrated in previous work (Grilli et al., 2004).

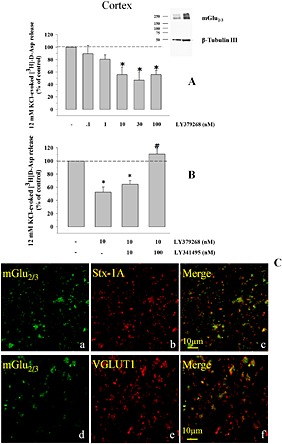

Figure 1.

Presynaptic release‐regulating mGlu2/3 autoreceptors in cortical nerve terminals of adult mice. (A) Concentration‐dependent inhibition of the 12 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp exocytosis by LY379268. Synaptosomes were transiently exposed to the depolarizing stimulus. When indicated, LY379268 was added concomitantly to the depolarizing stimulus. Results are expressed as percentage of the 12 mM KCl‐induced overflow (% of control). The [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow elicited by 12 mM KCl corresponded to 1.13 ± 0.09% of the total synaptosomal radioactivity, and it amounted to 1.5 ± 0.3 nCi. Data are the means ± SEM of four to seven experiments run in triplicate (three superfusion chambers for each experimental condition). *P < 0.05 versus the 12 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow. (A, inset) Western blot analysis unveiled the presence of mGlu2/3 receptor protein dimers in mouse cortical synaptosomes. Percoll‐purified synaptosomes were lysed as described in the Methods section, and lysates (5 μg protein, left lane; 10 μg protein, right lane) were immunoblotted and probed with anti‐mGlu2/3 antibody and with anti β‐tubulin antibodies. The figure shows a representative Western blot of five analyses carried out on different days. (B) Antagonism by LY341495 of the inhibitory effect of LY379268 (10 nM) on the 12 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from mouse cortical synaptosomes. Results are expressed as percentage of the 12 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow (% of control). Data are the means ± SEM of seven experiments run in triplicate. *P < 0.05 versus the 12 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow. # P < 0.05 versus the 12 mM KCl/10 nM LY379268‐evoked tritium overflow. (C) mGlu2/3 receptor proteins are present in Stx‐1A and VGLUT1‐positive nerve terminals isolated from the cortex of adult mice. Percoll‐purified synaptosomes were processed for immunocytochemistry and visualized by fluorescence microscopy as described in the Methods section. The figure shows representative images of four to seven independent experiments carried out in different days.

The Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of mGlu2/3 receptor proteins in synaptosomal lysates. The antibody recognized a component with a mass compatible with the presence of the dimeric assembly of mGlu2/3 receptor proteins (Figure 1A, inset). Furthermore, confocal microscopy revealed that mGlu2/3 immunoreactivity is expressed presynaptically in glutamatergic nerve endings. Cortical glutamatergic nerve endings were identified by using a selective antibody recognizing the VGLUT, while the presynaptic component of the synaptosomal particles was identified by using an antibody raised against Stx‐1A. As already shown in previous work (Musante et al., 2008a), mouse cortical synaptosomes efficiently stained for Stx‐1A (Figure 1C, panel a) and for VGLUT (Figure 1C, panel d). The mouse cortical synaptosomal preparation also efficiently stained for mGlu2/3 immunoreactivity (Figure 1C, panels b and e). A significant percentage of VGLUT positive particles and of Stx‐1A particles were immunopositive for the mGlu2/3 receptor (Figure 1D, panels c and f), confirming the existence of these receptors in cortical glutamatergic presynaptic terminals. Analysis of four different images revealed that about 71 ± 2% of the VGLUT positive particles and about 64 ± 4% of the Stx‐1A positive particles were positive for mGlu2/3 receptors respectively. Conversely, a significant percentage of mGlu2/3 positive particles were immunopositive for Stx‐1A (59 ± 4%; Figure 2C) and for VGLUT1 (64 ± 8%; Figure 2C) staining.

Figure 2.

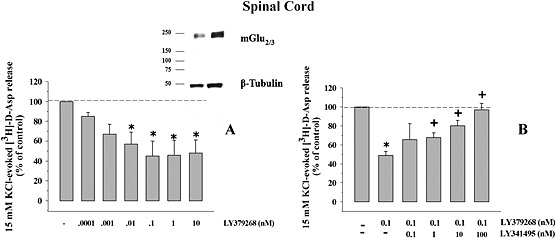

Presynaptic release‐regulating mGlu2/3 autoreceptors in spinal cord nerve terminals of adult mice. (A) Concentration‐dependent inhibition of the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp exocytosis by LY379268. Synaptosomes were stimulated as previously described. Results are expressed as percentage of the 15 mM KCl‐induced overflow (% of control). The [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow elicited by 15 mM KCl corresponded to 2.18 ± 0.21% of the total synaptosomal radioactivity, and it amounted to 2.63 ± 0.5 nCi. Data are the means ± SEM of six to nine experiments run in triplicate (three superfusion chambers for each experimental condition). *P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow. (A, inset) mGlu2/3 receptor protein dimers exist in mouse spinal cord synaptosomes. Synaptosomal lysates were immunoblotted (10 μg protein, left lane; 20 μg protein, right lane) and probed with anti‐mGlu2/3 antibody and with anti β‐tubulin antibodies. The figure shows a representative Western blot of six analyses. (B) Antagonism by LY341495 of the inhibitory effect of LY379268 (10 nM) on the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from mouse spinal cord synaptosomes. Results are expressed as percentage of the 15 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow. Data are the means ± SEM of six experiments run in triplicate. *P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow; + P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl/10 nM LY379268‐evoked tritium overflow.

Presynaptic mGlu2/3 autoreceptors in mouse spinal cord glutamatergic nerve endings

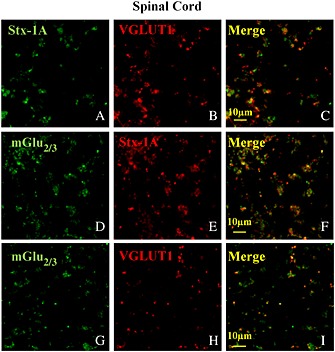

In previous studies, we demonstrated that a higher concentration (15 mM) of K+ ions is required to elicit tritium overflow from spinal cord nerve terminals that is comparable with that caused by 12 mM KCl from cortical synaptosomes (see for discussion Di Prisco et al., 2012). Notably, from previous data in the literature, it has been shown that the 15 mM KCL‐evoked release of [3H]‐d‐Asp was prevented when superfusion was carried out with a medium where Ca2 + ions were omitted (Milanese et al., 2011; Di Prisco et al., 2013), compatible with the exocytotic nature of the release process. The selective mGlu2/3 agonist LY379268 inhibited in a concentration‐dependent fashion the [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow evoked by 15 mM KCl. The agonist efficiently reduced the [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow (EC50 = 0.15 ± 0.37 pM; maximal inhibition: 54.85 ± 7.2%, reached at 0.1 nM, n = 6; Romei et al., 2013). To confirm the involvement of mGlu2/3 autoreceptors, the effect of LY379268 (0.1 nM) was then tested in the presence of increasing concentrations of the mGlu2/3 antagonist LY341495 (0.1–100 nM). As shown in Figure 2B, the antagonist concentration‐dependently prevented the 0.1 nM LY379268‐induced inhibition of [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow, being maximally active when added at 100 nM. At the maximal concentration applied, the antagonist failed to affect, on its own, the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow (data not shown). Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of mGlu2/3 immunoreactivity in spinal cord synaptosomal lysates. In particular, the anti mGlu2/3 antibody recognized a protein of about 230 kDa, corresponding to the expected mass of the receptor dimer assembly (Figure 2A, inset). Furthermore, confocal microscopy analysis showed significant mGlu2/3 immunostaining in spinal cord glutamatergic nerve endings. Mouse spinal cord synaptosomes efficiently stained for Stx‐1A (Figure 3C, panel a) and for VGLUT (Figure 3, panel d). A significant percentage of VGLUT1 positive particles were immunopositive for Stx‐1A immunostaining (74 ± 5%), and conversely, Stx‐1A positive particles were positive for VGLUT1 staining (60 ± 11%). Furthermore, these presynaptic glutamatergic particles were positive for mGlu2/3 immunoreactivity as suggested by the finding that a significant percentage of mGlu2/3 receptor‐positive particles were immunopositive for Stx‐1A and for VGLUT respectively (Figure 3, panels c and f). Analysis of eight different images revealed that about 68 ± 4% of the Stx‐1A positive particles and about 80 ± 3% of the VGLUT positive particles were positive for mGlu2/3 receptor immunostaining. Conversely, a significant percentage of mGlu2/3 positive particles were immunopositive for Stx‐1A (74 ± 5%; Figure 2C) and for VGLUT1 (64 ± 8%; Figure 2C).

Figure 3.

mGlu2/3 receptor proteins are present in Stx‐1A and VGLUT1‐positive nerve terminals isolated from the spinal cord of adult mice. Percoll‐purified synaptosomes were processed for immunocytochemistry and visualized by fluorescence microscopy as described in the Methods section. The figure shows representative images of eight independent experiments carried out on different days.

Pharmacological profile of the mGlu2/3 autoreceptors in mouse cortical and spinal cord terminals

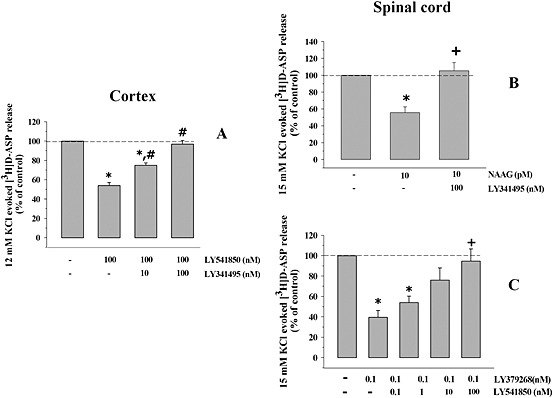

In order to better define the pharmacological profile of the mGlu2/3 autoreceptors involved in the control of glutamate exocytosis from cortical and spinal cord glutamatergic nerve endings, we investigated the effect of LY541850 and NAAG on the K+‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from both synaptosomal preparations.

LY541850 reduced in a concentration‐dependent fashion the 12 mM KCl‐evoked overflow of [3H]‐d‐Asp from cortical nerve endings (EC50 = 1.06 ± 0.56 nM; maximal inhibitory effect, −51.33 ± 4.28%, n = 5, observed when the compound was added at 100 nM; Figure 4A), but it failed to significantly affect the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from spinal cord nerve endings (Figure 4B), even when added at 1000 nM.

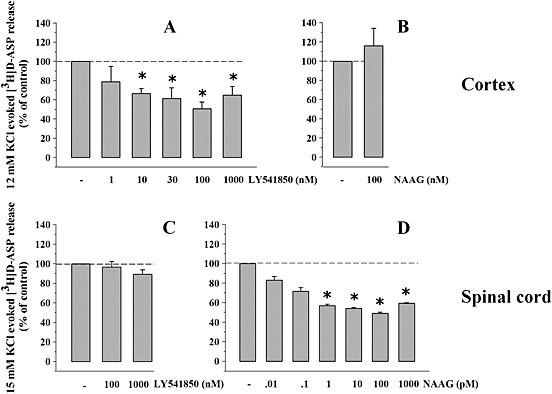

Figure 4.

Effects of NAAG and of LY541850 on the KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from mouse cortical and spinal cord synaptosomes. (A) Concentration‐dependent inhibition of the 12 mm KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp exocytosis by LY541850. Results are expressed as % of control. Data are the means ± SEM of five experiments run in triplicate. *P < 0.05 versus the 12 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow. (B) Effect of NAAG (100 nM) on the [3H]‐d‐Asp exocytosis elicited by 12 mM KCl from mouse cortical synaptosomes. Results are expressed as % of control. Data are the means ± SEM of six experiments run in triplicate. (C) Effect of LY541850 (100–1000 nM) on the [3H]‐d‐Asp exocytosis elicited by 15 mM KCl from mouse spinal cord synaptosomes. Results are expressed as % of control. Data are the means ± SEM of six experiments run in triplicate. (D) Concentration‐dependent inhibition of the [3H]‐d‐Asp exocytosis elicited by 15 mM KCl from spinal cord synaptosomes by NAAG. Results are expressed as % of control. Data are the means ± SEM of eight experiments run in triplicate. *P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow.

Conversely, 100 nM NAAG failed to affect the 12 mM KCl‐evoked release of [3H]‐d‐Asp from cortical synaptosomes (Figure 4C), but it significantly inhibited the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from spinal cord nerve endings (Figure 4D). In spinal cord synaptosomes, NAAG‐induced inhibition occurred in a concentration‐dependent fashion (EC50: 0.054 ± 0.003 pM; maximal inhibition, −49.18 ± 6.8%, n = 8, observed when the agonist was added at 100 pM; Figure 4D). A comparable potency was observed when studying the concentration–effect NAAG exerts on the 15 mM KCl‐evoked release of preloaded [3H]‐glycine from mouse spinal cord terminals (Romei et al., 2013). It has been proposed that unavoidable contamination by glutamate (about the 0.2–0.5%) of the NAAG (Fricker et al., 2009) might account for the NAAG‐induced effect at mGlu3 receptor subtypes. To test this hypothesis, experiments were carried out to investigate whether 1 nM glutamate (i.e. a concentration of glutamate corresponding to the highest concentration of NAAG tested in spinal cord synaptosomes; Figure 4D) could affect the 15 mM KCl‐evoked release of [3H]‐d‐Asp from spinal cord synaptosomes. The amino acid failed to modify the K+‐evoked glutamate exocytosis (15 mM KCl: 2.68 ± 0.09; 15 mM KCl/1 nM glutamate: 3.08 ± 0.15, results expressed as induced overflow; data are mean ± SEM of six experiments, n.s., please compare with Romei et al., 2013). These findings strongly indicate that NAAG, and not contaminating glutamate, accounts for its ability to activate mGlu2/3 receptors (Neale, 2011).

To confirm that the LY541850‐induced inhibition of the 12 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from cortical nerve endings relied on the activation of the presynaptic mGlu2/3 autoreceptors, we investigated the effect of LY541850 (100 nM) in the presence of increasing concentrations of the mGlu2/3 antagonist LY341495. Figure 5A shows that the antagonist significantly counteracted the 100 nM LY541850‐evoked inhibition of the 12 mM KCl‐evoked overflow of [3H]‐d‐Asp in cortical synaptosomes when added at 10 nM, but completely abolished it when added at 100 nM.

Figure 5.

Effects of agonists and antagonists on the KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from mouse cortical and spinal cord synaptosomes. (A) Antagonism by LY341495 of the LY541850‐induced inhibition of the 12 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from mouse cortical synaptosomes. Synaptosomes were exposed to 12 mM KCl in the presence and absence of 100 nM LY379268. When indicated, LY341495 (10–100 nM) was added concomitantly with the mGlu2/3 agonist. Results are expressed as % of control. Data are the means ± SEM of five experiments run in triplicate. *P < 0.05 versus the 12 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow; # P < 0.05 versus the 12 mM KCl/100 nM LY341495‐evoked tritium overflow; ## P < 0.01 versus the 12 mM KCl/100 nM LY341495‐evoked tritium overflow. (B) Antagonism by LY341495 of the NAAG‐induced inhibition of the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from mouse spinal cord synaptosomes. Synaptosomes were exposed to 15 mM KCl in the presence and absence of 10 pM NAAG. When indicated, 100 nM LY341495 was added concomitantly with the mGlu2/3 agonist. Results are expressed as % of control. Data are the means ± SEM of six experiments run in triplicate. *P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow; + P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl/0.1 pM NAAG‐evoked tritium overflow. (C) Antagonism by LY541850 of the LY379268‐induced inhibition of the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from mouse spinal cord synaptosomes. Synaptosomes were exposed to 15 mM KCl in the presence and absence of 100 nM LY379268. When indicated, LY341495 (0.1–100 nM) was added concomitantly with the mGlu2/3 agonist. Results are expressed as % of control. Data are the means ± SEM of seven experiments run in triplicate. *P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow; + P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl/0.1 nM LY379268‐evoked tritium overflow.

In spinal cord synaptosomes, NAAG‐induced inhibition was tested in the presence of 100 nM LY341495, to verify whether this effect relies on mGlu2/3 autoreceptors. Figure 5B shows that 100 nM LY341495 efficiently prevented the 10 pM NAAG‐induced inhibition of [3H]‐d‐Asp exocytosis. Finally, LY541850, inactive on its own on the 15 mM KCl‐induced [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from spinal cord synaptosomes, was tested for its efficacy in antagonizing the LY379268‐induced inhibition of the tritium release. Figure 5C shows that LY541850 concentration‐dependently antagonized the 0.1 nM LY379268‐induced inhibition of the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow, being maximally active when added at 100 nM.

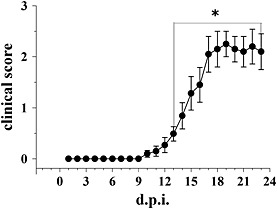

EAE mice and clinical score

Female mice (8 weeks old) were immunized with the MOG35–55, and the clinical symptoms were scored daily. Figure 6 shows that disease onset became evident at day 13 ± 1 after immunization, when the media score value amounted to 0.49 ± 0.05 and it occurred in 51.4% of the MOG‐injected mice (n = 22 mice). The maximum disease score was observed at 21 ± 1 d.p.i., it amounted to 2.12 ± 0.52 (n = 10 mice) and it did not vary significantly until 24 d.p.i. The cumulative score was 19.58 ± 2.12 (n = 10 mice).

Figure 6.

Clinical scores in EAE mice at different stages of disease. Clinical signs were monitored daily in EAE mice and are expressed as average (median ± SEM). *P < 0.05 versus 1 d.p.i.

Effects of LY379268 on the [3H]‐d‐Asp release from cortical and spinal cord nerve endings from EAE mice at different stages of disease

Cortical and spinal cord synaptosomes were isolated from control (non‐immunized) and EAE mice at different stages of disease, and the release of [3H]‐d‐Asp elicited by high K+ was monitored.

The KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow was dramatically reduced from synaptosomes isolated from the cortex of EAE mice at the early stage of disease (13 d.p.i.), but it was significantly increased from nerve terminals isolated from the spinal cord of EAE mice at the acute stage of disease (21 d.p.i., Table 1, but see Di Prisco et al., 2013, 2014a, 2014b).

Table 1.

Effects of LY379268 on the release of preloaded [3H]‐d‐Asp elicited by high KCl from cortical and spinal cord nerve endings from non‐immunized and EAE mice

| Control mice (induced overflow) | % of changes versus control | EAE mice (induced overflow) | % of changes versus control | % of changes versus EAE mice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortex 12 mM KCl | 1.16 ± 0.05 | 0.75 ± 0.02 a | −35.34 ± 5.33 | ||

| 12 mM KCl/10 nM LY379268 | 0.63 ± 0.03 a | −45.68 ± 5.87 a | 0.63 ± 0.09 | −15.6 ± 4.11 | |

| Spinal cord 15 mM KCl | 2.16 ± 0.06 | 3.07 ± 0.09 b | +42.12 ± 4.63 | ||

| 15 mM KCl/10 nM LY379268 | 1.37 ± 0.26 b | −36.57 ± 3.88 | 2.11 ± 0.07 c | −31.27 ± 3.15 |

Synaptosomes from control (non‐immunized) and from EAE mice (at 13 d.p.i. when studying then 12 mM KCl‐evoked release of [3H]‐d‐Asp from cortical nerve endings and at 21 d.p.i. when studying then 15 mM KCl‐evoked release of [3H]‐d‐Asp from spinal cord nerve endings) were exposed in superfusion to the depolarizing stimulus; 10 nM LY379268 was added concomitantly when indicated. Results are expressed as induced overflow as well as percentage of change versus control. Data are the mean ± SEM of at least four experiments run in triplicate (three superfusion chambers for each experimental condition).

P < 0.05 versus 12 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp from cortical nerve endings of non‐immunized mice.

P < 0.05 versus 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp from spinal cord nerve endings of non‐immunized mice.

P < 0.05 versus 15 mM KCl/10 nM LY379268‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp from cortical nerve endings of EAE mice.

LY379268 (10 nM) almost halved glutamate exocytosis from both cortical and spinal cord synaptosomes isolated from control mice (Table 1). Conversely, the drug was ineffective in cortical synaptosomes from EAE mice at 13 d.p.i. In particular, LY379268 (10 nM) slightly, although not significantly, inhibited the tritium exocytosis from EAE mouse cortical terminals (Table 1). In contrast, LY379268 (10 nM) efficiently inhibited glutamate overflow from spinal cord synaptosomes from EAE mice at 21 d.p.i. (Table 1). We did not perform experiments in cortical synaptosomes from EAE mice at 21 d.p.i., because glutamate defects observed early at 13 d.p.i. did not recover at this stage of the disease.

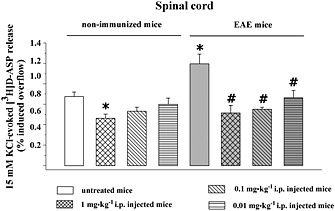

[3H]‐d‐Asp release in spinal cord nerve endings from EAE mouse at the acute stage of disease: effects of in vivo LY379268

The efficacy of LY379268 in controlling glutamate exocytosis from EAE mouse spinal cord synaptosomes prompted us to investigate whether the acute in vivo administration of this drug could modify the release capability at these terminals. With this aim, control and EAE mice at 21 d.p.i. were randomly assigned to the following groups: control untreated mice, control LY379268‐administered mice, EAE untreated mice and EAE LY379268‐administered mice. LY379268 (1–0.01 mg·kg−1) was acutely administered i.p. (Woolley et al., 2008). Animals were then killed within 3 h of the drug injection, and spinal cord synaptosomes were prepared to monitor the 15 mM K+‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow in ex vivo, in vitro experiments. Figure 7 shows that in control mice, the acute in vivo administration of LY379268 (1 mg·kg−1) caused adaptive modifications to glutamate overflow at the spinal cord level. These changes were retained by the presynaptic nerve terminals isolated from this region and could be detected as reduced exocytosis capability in ex vivo, in vitro experiments. Indeed, the 15 mM K+‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from nerve terminals isolated from the spinal cord of LY379268 (1 mg·kg−1)‐administered control mice was significantly lower (−31.36 ± 4.89%, n = 7) than that observed in synaptosomes isolated from the spinal cord of control untreated mice. A lower dose (0.1 mg·kg−1) of LY379268 slightly, although not significantly, reduced glutamate overflow (−19.39 ± 5.12%, n = 7), while the lowest dose applied (0.01 mg·kg−1) was almost ineffective (−9.91 ± 5.01%, n = 4). In contrast, the acute in vivo administration of LY379268 (1.0–0.01 mg·kg−1) in EAE mice at the acute stage of the disease caused a strikingly significant reduction of in vitro 15 mM K+‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp release from spinal cord nerve endings. Notably, this LY379268‐induced effect was observed in spinal cord synaptosomes isolated from EAE mice administered lower doses of the drug, which did not affect significantly glutamate exocytosis in control mouse spinal cord nerve endings. The in vivo LY379268‐induced inhibition of the in vitro glutamate exocytosis amounted to −48.20 ± 6.82% in mice administered 1 mg·kg−1 LY379268, to −44.58 ± 3.65% in mice administered 0.1 mg·kg−1 LY379268 and to −33.33 ± 7.43% in mice administered 0.01 mg·kg−1 LY379268.

Figure 7.

Effect of acute in vivo administration of LY379268 on the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow from synaptosomes isolated from the spinal cord of control (non‐immunized) and EAE mice. Control (untreated) mice and EAE (grey bar) mice at the acute stage of disease (21 d.p.i.) were acutely injected i.p. (doses as indicated) and then killed within 3 h. The spinal cord was rapidly removed, and synaptosomes were prepared to monitor the 15 mM KCl‐evoked [3H]‐d‐Asp overflow in in vitro experiments. Results are expressed as 15 mM KCl‐induced overflow; data are means of nine experiments run in triplicate. *P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow from untreated mice; # P < 0.05 versus the 15 mM KCl‐evoked tritium overflow from untreated EAE mice.

Discussion

The first finding of our study is that mGlu2/3 autoreceptors located in cortical and spinal cord glutamatergic nerve endings have different pharmacological profiles and could represent different receptor subtypes belonging to the group II of mGlu receptors. In particular, LY379268, at nanomolar concentrations, activates the mGlu2/3 receptor subtype located presynaptically on cortical glutamatergic nerve endings. The inhibitory effect exerted by the agonist was efficiently prevented by the broad‐spectrum antagonist LY341495 but could not be mimicked by NAAG, even when the ligand was applied at micromolar concentrations. Similar to what was observed in the cortex, the mGlu2/3 autoreceptors located on glutamatergic spinal cord nerve endings were efficiently activated by LY379268. The apparent affinity of LY379268 in spinal cord nerve endings, however, was at least four orders of magnitude higher than that observed in the cortex (0.15 ± 0.37 pM vs. 1.50 ± 1.15 nM), suggesting the existence of a high‐affinity LY379268‐sensitive binding site on spinal cord terminals and of a low‐affinity LY379268‐sensitive binding site on cortical nerve terminals. In spinal cord terminals, the inhibitory effect exerted by LY379268 was efficiently prevented by LY341495; NAAG inhibited glutamate exocytosis very efficiently, in a LY341495‐sensitive way, with an apparent affinity (0.16 ± 0.28 pM) almost the same as that of LY379268 in these terminals.

These observations led us to propose that the two autoreceptors could represent different receptor subtypes having different pharmacological profiles. This hypothesis was definitively supported by the results obtained with LY541850. Before discussing the data obtained with this compound, it is important to recall the features of our technique that make it an approach of choice to study the pharmacological profile of compounds with a double‐faced (agonist/antagonist) profile such as LY541850,(Dominguez et al., 2005; Hanna et al., 2013). In superfused synaptosomes, receptor‐mediated effects are elicited only by agonist(s) exogenously added in the superfusion medium, because antagonist(s) are expected to be unable to modify on their own neurotransmitter release (Raiteri et al., 1974; Marchi et al., 2015), provided that the receptors they bind to did not adopt a constitutive active conformation (Musante et al., 2008b; Rossi et al., 2013). Well in line with previous observations, LY541850 mimicked LY379268 in cortical synaptosomes in a LY341495‐sensitive manner, compatible with an agonist‐like activity at mGlu2/3 autoreceptors. However, LY541850 failed to affect glutamate exocytosis in spinal cord nerve endings, but it efficiently prevented the effect of LY379268, compatible with an antagonist‐like activity in these terminals. On the basis of these observations, we propose that the two mGlu2/3 receptors could belong to different receptor subtypes, typified by a different mGlu2/3 receptor subunit assembly. The relative contribution of the two receptor subunits in the expression of the two autoreceptors, however, could be hardly predicted on the basis of the present results. The most conservative conclusion could be that homomeric mGlu2 receptors exist in cortical glutamatergic nerve terminals, while mGlu3 receptor homodimers are present in spinal cord synaptosomes. This hypothesis is supported by data in the literature demonstrating the existence of homomeric mGlu receptors belonging to the II group in selected CNS regions (Hanna et al., 2013) and in different cell subtypes (Durand et al., 2014). However, it is also widely recognized that mGlu receptors belonging to the same group (i.e. the mGlu2 and mGlu3 receptors) also could associate to form heterodimers as well as dimeric associations of dimers (Doumazane et al., 2010; Kammermeier, 2012). The existence of mGlu2/mGlu3 receptor heterodimers in both cortical and spinal cord terminal autoreceptors typified by a certain complexity of subunit assembly, therefore, deserves consideration. For instance, there is evidence that primary afferent terminals in the dorsal horn are endowed with mGlu2 receptors (Chiechio et al., 2002), which could presynaptically control glutamate release at these terminals (Gerber et al., 2000), suggesting that also mGlu2 receptor subunits could have a role as autoreceptors in this CNS region. The Western blot analysis with antibody recognizing the mGlu2/mGlu3 receptor subunit confirmed the presence of receptor proteins in synaptosomal lysates. It should, however, be stressed that, although antibodies separating between mGlu2 and mGlu3 receptors are available, synaptosomes isolated from a selected brain region represent an heterogeneous population of synaptosomal subfamilies, each one could be endowed with mGlu2/3 receptors having different subunit compositions. The immunohistochemical approach did not allow us to identify the presence of a receptor subtype on specific nerve endings.

Recent evidence suggests that impaired central neurotransmission is important in determining the progression of MS (Schwartz et al., 2003; Lanz et al., 2007). In particular, altered glutamate levels have been observed in the CSF of MS patients (Sarchielli et al., 2007), as well as in animals suffering from demyelinating disorders. Depending on the animal model used and the brain region under study, opposite modifications of glutamate release capability were observed in selected CNS regions, indicating that glutamate impairment in MS is a complex event. In particular, increased glutamate release was detected in the spinal cord of EAE rats (Sulkowski et al., 2009) and mice (Di Prisco et al., 2013, 2014a, 2014b) as well as in striatal and spinal cord nerve terminals of EAE mice (Centonze et al., 2009; Marte et al., 2010; Di Prisco et al., 2013, 2014a, 2014b), while reduced glutamate release was observed in cortical nerve endings of both mice and rats suffering from EAE (Vilcaes et al., 2009; Di Prisco et al., 2013, 2014a, 2014b). As for glutamate receptors, previous studies have shown that both mGlu1/5 and mGlu4 receptors are suitable targets of drugs for ameliorating MS symptoms (Besong et al., 2002; Fazio et al., 2008, 2014, Fallarino et al., 2010). Whether mGlu2/3 autoreceptors undergo adaptive changes in the CNS of EAE mice and whether they could be suitable targets for MS therapeutics has so far been poorly investigated (Geurts et al., 2003; Taylor et al., 2005; Pinteaux‐Jones et al., 2008).

The second finding of our study was that in mice suffering from EAE, the mGlu2‐preferring autoreceptors in cortical nerve ending selectively lost their ability to control glutamate exocytosis, while mGlu3‐preferring autoreceptors in spinal cord terminals were unmodified or their releasing efficiency even improved in these mice.

The loss of function of cortical mGlu2‐preferring autoreceptors was in a way unexpected, considering that mGlu2 receptors are predicted to be resistant to desensitization (Iacovelli et al., 2009). Other adaptive events, however, could account for the decreased efficacy of the mGlu2‐preferring autoreceptors in the cortex of EAE mice, including for instance the impairment of an intraterminal enzymatic pathway(s) that subserves effects mediated by the mGlu2/3 receptors. As already stated, mGlu2/3 receptor‐mediated functions mainly rely on the inhibition of the AC/cAMP pathway (Nicoletti et al., 2011). Interestingly, in EAE mice, this enzymatic pathway was significantly hampered in cortical nerve endings, but not in spinal cord terminals, where, on the contrary, it was even potentiated (Di Prisco et al., 2013, 2014a, 2014b). These enzymatic impairments might be responsible for the loss of efficacy of LY379268 in the cortex and could also explain the gain in efficacy of LY379268 in controlling glutamate exocytosis from spinal cord terminals of EAE mice.

Well in line with these observations, the third finding of our study was that in vivo LY379268 in EAE mice at the acute stage of the disease triggers in vivo adaptive changes at glutamatergic spinal cord terminals that could be observed in in vitro studies as inhibition of glutamate exocytosis. In particular, the amount of [3H]‐d‐Asp released upon a depolarizing stimulus that was applied was quantitatively comparable with that detected from the spinal cord terminals of control untreated animals. Interestingly, the restoration of glutamate exocytosis to physiological levels in spinal cord glutamatergic nerve endings of EAE mice was observed following the acute administration of very low doses (1 to 0.01 mg·kg−1) of LY379268, which are devoid of activity in non‐immunized mice. Again, the increased activity of the AC/cAMP pathway observed in EAE mouse spinal cord at the acute stage of disease might account for the higher potency of in vivo LY379268 in reducing glutamate exocytosis in this CNS region. Notably, NAAG regulates the endogenous production of cAMP in astrocytes more efficiently than glutamate (Wrobleska et al., 1998).

Although, so far, there are no mGlu receptor ligands close to approval for clinical trials (Nicoletti et al., 2015), mGlu receptors (including mGlu2 and mGlu3 receptors) are still considered promising targets for the development of drugs for the treatment of CNS disorders, including MS. Indeed, it was recently proposed that MS patients with cognitive impairment had low hippocampal NAAG levels, suggesting that reduced availability of this endogenous ligand could have a role in the onset of the disease symptoms. If this is the case, agonist(s) at mGlu3‐preferring receptors as well as drugs that impede the enzymatic breakdown of NAAG might be beneficial in this disease. Accordingly, inhibitors of glutamate carboxypeptidase II, that is, the enzyme catalyzing the cleavage of endogenous NAAG to N‐acetyl aspartate and glutamate, were shown to increase the endogenous CNS level of NAAG and to be efficacious in preventing clinical symptoms in MS patients (Rahn et al., 2012 and the references therein).

To conclude, our findings support the notion that mGlu3‐preferring receptors could be preferential targets for the treatment of MS and CNS diseases. It should be noted that mGlu3 receptors have been targeted in several animal models of clinical disorders (traumatic brain injury, pain, schizophrenia, stoke and neurotoxicity) via the application of Glutamate carboxypeptidase II (CGPII) inhibitors and the subsequent receptor activation by elevated levels of NAAG as well as via application of heterospecific group II agonists (Monn et al., 2015; Nicoletti et al., 2015). We propose that the gain of function of the mGlu3‐preferring autoreceptors in EAE mice spinal cord concurs with the potential therapeutic efficacy of mGlu3 ligands.

Author contributions

S.D.P. performed release experiments. E.M. performed release experiments and EAe immunization. T.B. performed release experiments. G.O. performed Western Blot experiments. C.C. performed confocal experiments. M.G. performed data analysis. C.U. performed confocal analysis. M.M. planned the experiments, evaluated and discussed the results. A.P. planned the experiments, evaluated and discussed the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of transparency and scientific rigour

This Declaration acknowledges that this paper adheres to the principles for transparent reporting and scientific rigour of preclinical research recommended by funding agencies, publishers and other organizations engaged with supporting research.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by University of Genoa (Fondi per la Ricerca di Ateneo). The authors thank Dr James Monn for scientific discussion. The authors thank Maura Agate and Silvia Smith, PhD (University of Utah, School of Medicine), for editorial assistance.

Di Prisco, S. , Merega, E. , Bonfiglio, T. , Olivero, G. , Cervetto, C. , Grilli, M. , Usai, C. , Marchi, M. , and Pittaluga, A. (2016) Presynaptic, release‐regulating mGlu2‐preferring and mGlu3‐preferring autoreceptors in CNS: pharmacological profiles and functional roles in demyelinating disease. British Journal of Pharmacology, 173: 1465–1477. doi: 10.1111/bph.13442.

References

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA (2011). Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC), 5th edition Br J Pharmacol 164: S1‐324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Davenport AP, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, et al. (2015a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein‐coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol 172: 5744–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Kelly E, Marrion N, Peters JA, Benson HE, Faccenda E, et al. (2015b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Transporters. Br J Pharmacol 172: 6110–6202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besong G, Battaglia G, D'Onofrio M, Di Marco R, Ngomba RT, Storto M, et al. (2002). Activation of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibits the production of RANTES in glial cell cultures. J Neurosci 22: 5403–5411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J, Fagni L, Pin J‐P (2002). Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs). Structure and function In: Egebjerg J, Schousboe A, Krogsgaard‐Larsen P. (eds). Glutamate and GABA Receptors and Transporters. Structure, Function and Pharmacology. Taylor & Francis: London and New York, pp. 121–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cartmell J, Schoepp DD (2000). Regulation of neurotransmitter release by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurochem 75: 889–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Muzio L, Rossi S, Cavasinni F, De Chiara V, Bergami A, et al. (2009). Inflammation triggers synaptic alteration and degeneration in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurosci 29: 3442–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiechio S, Caricasole A, Barletta E, Storto M, Catania MV, Copani A, et al. (2002). L‐Acetylcarnitine induces analgesia by selectively up‐regulating mGlu2 metabotropic glutamte receptors. Mol Pharmacol 61: 989–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis MJ, Bond RA, Spina D, Ahluwalia A, Alexander SPA, Giembycz MA, et al. (2015). Experimental design and analysis and their reporting: new guidance for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3461–3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco S, Summa M, Chellakudam V, Rossi PIA, Pittaluga A (2012). RANTES‐mediated control of excitatory amino acid release in mouse spinal cord. J Neurochem 121: 428–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco S, Merega E, Milanese M, Summa M, Casazza S, Raffaghello L, et al. (2013). CCL5‐glutamate interaction in central nervous system: early and acute presynaptic defects in EAE mice. Neuropharmacology 75: 337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco S, Merega E, Lanfranco M, Casazza S, Uccelli A, Pittaluga A (2014a). Acute desipramine restores presynaptic cortical defects in murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by suppressing central CCL5 overproduction. Br J Pharmacol 171: 2457–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco S, Merega E, Pittaluga A (2014b). Functional adaptation of presynaptic chemokine receptors in EAE mouse central nervous system. Synapse 68: 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez L, Prieto L, Valli MJ, Massey SM, Bures M, Wright RA, et al. (2005). Methyl substitution of 2‐aminobicyclo[3.1.0]‐hexane 2,6‐dicarboxylate (LY354740) determines functional activity at metabotropic glutamate receptors: identification of a subtype selective mGlu2 receptor agonist. J Med Chem 48: 3605–3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumazane E, Scholler P, Zwier JM, Trinquet E, Rondard P, Pin JP (2010). A new approach to analyze cell surface protein complexes reveals specific heterodimeric metabotropic glutamate receptors. FASEB J 25: 66–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand D, Carniglia L, Beauquis J, Caruso C, Saravia F, Lasaga M (2014). Astroglial mGlu3 receptors promote alpha‐secretase‐mediated amyloid precursor protein cleavage. Neuropharmacology 79: 180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallarino F, Volpi C, Fazio F, Notartomaso S, Vacca C, Busceti C et al. (2010). Metabotropic glutamate receptor‐4 modulates adaptive immunity and restrains neuroinflammation. Nat Med 16: 897‐902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio F, Notartomaso S, Aronica E, Storto M, Battaglia G, Vieira E, et al. (2008). Switch in the expression of mGlu1 and mGlu5 metabotropic glutamate receptors in the cerebellum of mice developing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and in autoptic cerebellar samples from patients with multiple sclerosis. Neuropharmacology 55: 491–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio F, Zappulla C, Notartomaso S, Busceti C, Bessede A, Scarselli P, et al. (2014). Cinnabarinic acid, an endogenous agonist of type‐4 metabotropic glutamate receptor, suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Neuropharmacology 81: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker AC, Mok MS, De la Flor R, Shah AJ, Woolley M, Dawson LA, et al. (2009). Effects of N‐acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG) at group II mGluRs and NMDAR. Neuropharmacology 56: 1060–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts JJG, Wolswijk G, Bö L, Van Der Valk P, Polman CH, Troost D, et al. (2003). Altered expression patterns of group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptors in multiple sclerosis. Brain 126: 1755–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber G, Zhong J, Youn D, Randic M (2000). Group II and group III metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists depress synaptic transmission in the rat spinal cord dorsal horn. Neuroscience 100: 393–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilli M, Raiteri L, Pittaluga A (2004). Somatostatin inhibits glutamate release from mouse cerebrocortical nerve endings through presynaptic sst2 receptor linked to the adenylyl cyclase‐protein kinase A pathway. Neuropharmacology 46: 388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna L, Ceolin L, Lucas S, Monn J, Johnson B, Collingridge G, et al. (2013). Differentiating the roles of mGlu2 and mGlu3 receptors using LY541850, an mGlu2 agonist/mGlu3 antagonist. Neuropharmacology 66: 114–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovelli L, Molinaro G, Battaglia G, Motolese M, Di Menna L, Alfiero M, et al. (2009). Regulation of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors by G protein‐coupled receptor kinases: mGlu2 receptors are resistant to homologous desensitization. Mol Pharmacol 75: 991–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW (2009). The glutamate homeostasis hypothesis of addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 561–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammermeier PJ (2012). Functional and pharmacological characteristics of metabotropic glutamate receptors 2/4 heterodimers. Mol Pharmacol 82: 438–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz M, Hahn HK, Hildebrandt H (2007). Brain atrophy and cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: a review. J Neurol 254: II43–II48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luccini E, Musante V, Neri E, Raiteri M, Pittaluga A (2007). N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate autoreceptors respond to low and high agonist concentrations by facilitating, respectively, exocytosis and carrier‐mediated release of glutamate in rat hippocampus. J Neurosci Res 85: 3657–3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luján R, Roberts JDB, Shigemoto R, Ohishi H, Somogyi P (1997). Differential plasma membrane distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR1α, mGluR2 and mGluR5, relative to neurotransmitter release sites. J Chem Neuroanat 13: 219–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchi M, Grilli M, Pittaluga A (2015). Nicotinic modulation of glutamate receptor function at nerve terminal level: a fine‐tuning of synaptic signals. Front Pharmacol 6: 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marte A, Cavallero A, Morando S, Uccelli A, Raiteri M, Fedele E (2010). Alterations of glutamate release in the spinal cord of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurochem 115: 343–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Lilley E (2015). Implementing guidelines on reporting research using animals (ARRIVE etc.): new requirements for publication in BJP. Br J Pharmacol 172: 3189–3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanese M, Zappettini S, Onofri F, Musazzi L, Tardito D, Bonifacino T, et al. (2011). Abnormal exocytotic release of glutamate in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem 116: 1028–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monn JA, Prieto L, Taboada L, Pedregal C, Hao J, Reinhard MR, et al. (2015). Synthesis and pharmacological characterization of C4‐disubstituted analogs of 1S,2S,5R,6S‐2‐aminobicyclo[3.1.0]hexane‐2,6‐dicarboxylate: identification of a potent, selective metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist and determination of agonist‐bound human mGlu2 and mGlu3 amino terminal domain structures. J Med Chem 58: 1776–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musante V, Neri E, Feligioni M, Puliti A, Pedrazzi M, Conti V, et al. (2008a). Presynaptic mGlu1 and mGlu5 autoreceptors facilitate glutamate exocytosis from mouse cortical nerve endings. Neuropharmacology 55: 474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musante V, Longordo F, Neri E, Pedrazzi M, Kalfas F, Severi P, et al. (2008b). RANTES modulates the release of glutamate in human neocortex. J Neurosci 28: 12231–12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musante V, Summa M, Cunha RA, Raiteri M, Pittaluga A (2011). Pre‐synaptic glycine GlyT1 transporter–NMDA receptor interaction: relevance to NMDA autoreceptor activation in the presence of Mg2 + ions. J Neurochem 117: 516–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale JH (2011). N‐Acetylaspartylglutamate is an agonist at mGluR3 in vivo and in vitro. J Neurochem 119: 891–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti F, Bockaert J, Collingridge GL, Conn PJ, Ferraguti F, Schoepp DD, et al. (2011). Metabotropic glutamate receptors: from the workbench to the bedside. Neuropharmacology 60: 1017–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti F, Bruno V, Ngomba RT, Gradini R, Battaglia G (2015). Metabotropic glutamate receptors as drug targets: what's new? Curr Opin Pharmacol 20: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswender CM, Conn PJ (2010). Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 50: 295–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski RT, Janczura KJ, Ball SR, et al. (2012). NAAG peptidase inhibitors block cognitive deficit induced by MK‐801 and motor activation induced by d‐amphetamine in animal models of schizophrenia. Transcult Psychiatry. doi:10.1038/tp2012.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ1, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin J‐P, Duvoisin R (1995). The metabotropic glutamate receptors: structure and functions. Neuropharmacology 34: 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinteaux‐Jones F, Sevastou IG, Fry VA, Heales S, Baker D, Pocock JM (2008). Myelin‐induced microglial neurotoxicity can be controlled by microglial metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurochem 106: 442–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn KA, Watkins CC, Alt J, Rais R, Stathis M, Grishkan I, et al. (2012). Inhibition of glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII) activity as a treatment for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 20101–20106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiteri M, Angelini F, Levi G (1974). A simple apparatus for studying the release of neurotransmitters from synaptosomes. Eur J Pharmacol 25: 411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romei C, Raiteri M, Raiteri L (2013). Glycine release is regulated by metabotropic glutamate receptors sensitive to mGluR2/3 ligands and activated by N‐acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG). Neuropharmacology 66: 311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi PIA, Musante I, Summa M, Pittaluga A, Emionite L, Ikehata M, et al. (2013). Compensatory molecular and functional mechanisms in nervous system of the Grm1crv4 mouse lacking the mGlu1 receptor: a model for motor coordination deficits. Cereb Cortex 23: 2179–2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger H, Hanna L, Colvin EM, Grubisha O, Ursu D, Heinz BA, et al. (2013). Pharmacological profiling of native group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in primary cortical neuronal cultures using a FLIPR. Neuropharmacology 66: 264–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarchielli P, Di Filippo M, Candeliere A, Chiasserini D, Tenaglia S, Bonucci M, et al. (2007). Expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor GLUR3 and effects of glutamate on MBP‐ and MOG‐specific lymphocyte activation and chemotactic migration in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neuroimmunol 188: 146–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz M, Shaked I, Fisher J, Mizrahi T, Shori H (2003). Protective autoimmunity against the enemy within: fighting glutamate toxicity. Trends Neurosci 26: 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowski G, Dąbrowska‐Bouta B, Kwiatkowska‐Patzer B, Strużyńska L (2009). Alterations in glutamate transport and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat brain during acute phase of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Folia Neuropathol 47: 327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summa M, Di Prisco S, Grilli M, Usai C, Marchi M, Pittaluga A (2013). Presynaptic mGlu7 receptors control GABA release in mouse hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 66: 215–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaru Y, Nomura S, Mizuno N, Shigemoto R (2001). Distribution of metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR3 in the mouse CNS: differential location relative to pre‐and postsynaptic sites. Neuroscience 106: 481–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DL, Jones F, Kubota ES, Pocock JM (2005). Stimulation of microglial metabotropic glutamate receptor mGlu2 triggers tumor necrosis factor alpha‐induced neurotoxicity in concert with microglial‐derived Fas ligand. J Neurosci 25: 2952‐2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilcaes AA, Furlan G, Roth GA (2009). Inhibition of Ca2 +‐dependent glutamate release from cerebral cortex synaptosomes of rats with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neurochem 108: 881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley ML, Pemberton DJ, Bate S, Corti C, Jones DNC (2008). The mGlu2 but not the mGlu3 receptor mediates the actions of the mGluR2/3 agonist, LY379268, in mouse models predictive of antipsychotic activity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 196: 431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobleska B, Santi MR, Neale JH (1998). N‐acetylaspartylglutamate activates cAMP‐coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors in cerebellar astrocytes. Glia 24: 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobleska B, Wegorzewska IN, Bzdega T, Olszewski RT, Neale JH (2006). Differential negative coupling of type 3 metabotropic glutamate receptor to cyclic GMP levels in neurons and astrocytes. J Neurochem 96: 1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappia E, Casazza S, Pedemonte E, Benvenuto F, Bonanni I, Gerdoni E, et al. (2005). Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T‐cell anergy. Blood 106: 1755–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]