Abstract

Patient: Male, 71

Final Diagnosis: Neuroendocrine cancer bladder

Symptoms: Dysuria • haematuria

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Transurethral resection of the bladder tumor

Specialty: Oncology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder is a rare and aggressive form of bladder cancer that mainly presents at an advanced stage. As a result of its rarity, it has been described in many case reports and reviews but few retrospective and prospective trials, showing there is no standard therapeutic approach. In the literature the best therapeutic strategy for limited disease is the multimodality treatment and most authors have extrapolated treatment algorithms from the therapy recommendations of small cell lung cancer.

Case Report:

A 71-year-old male patient was referred to our hospital with gross hematuria and dysuria. Imaging and cystoscopy revealed a vegetative lesion of the bladder wall. A transurethral resection of the bladder was performed. Pathological examination revealed a pT2 high-grade urothelial carcinoma with widespread neuroendocrine differentiation. Multimodal treatment with neoadjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy was performed. A CT scan performed after chemotherapy demonstrated a radiological complete response. The patient underwent radical cystectomy and lymphadenectomy. The histopathological finding of bladder and node specimen confirmed a pathological complete response. A post-surgery CT scan showed no evidence of local or systemic disease. Six months after surgery, the patient is still alive and disease-free.

Conclusions:

A standard treatment strategy of small cell cancer of the urinary bladder is not yet well established, but a multimodal treatment of this disease is the best option compared to surgical therapy alone. The authors confirm the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in limited disease of small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder.

MeSH Keywords: Carcinoma, Neuroendocrine; Carcinoma, Small Cell; Combined Modality Therapy; Neoadjuvant Therapy

Background

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) of the urinary bladder are the most common of all genitourinary tract NETs and include small cell carcinomas (SCCs), which is the most frequent, large cell carcinomas (LCCs), and the typical or atypical carcinoids [1].

SCC of the urinary bladder (SCCUB) is a rare and poorly-differentiated kind of bladder cancer, accounting for less than 1% of all primary bladder carcinomas [2], and it generally coexists with transitional cells carcinoma [3]. NET is associated with more aggressive behavior and worse prognosis compared to transitional cells carcinomas of the urinary bladder (UCUB) [4], and similarly to SCCs, usually arise in other organs. More than 95% of SCCUB presents at diagnosis in an advanced local stage (pT2 or pT3), with a metastatic potential risk higher than transitional cell carcinoma [5,6]. SCCUB primarily affects Caucasian males age 60–80 years, mostly with a history of heavy smoking. Gross hematuria, with or without dysuria, depending on the site of the lesion, is the most common clinical manifestation but the diagnosis is based on pathological specimen after transurethral resection of the bladder (TURB) [4].

Since the first reported case published in 1981 by Cramer et al. [7], SCCUB has been described in a large series of case reports and literature reviews but there have been only in few retrospective and prospective trials [8]. As a result of its rarity, there is no consensus on a standard therapeutic approach for SCCUB. Many authors have extrapolated algorithm treatments of this rare tumor from the therapy recommendations of small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), since both tumors show similar histology and biological behavior [9]. Radical cystectomy alone or followed by adjuvant chemotherapy are the mainstay treatment of SCCUB [10] but both therapeutic options show poor outcomes in terms of patient survival. Few retrospective series [11–13] or prospective clinical trials [14] reported an increased survival [15] with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical cystectomy, especially in limited disease (LD), due to the high metastatic potential of SCCUB, also at an early stage. The most common chemotherapy regimens used for neoadjuvant treatment protocols of SCCUB include a cisplatin plus etoposide regimen, as for the pulmonary counterpart [16,17].

The purpose of this paper is to present a successfully treated case of SCCUB, with a complete response, by means of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical cystectomy, in order to show the effectiveness of the currently available treatment of this rare tumor.

Case Report

A 71-year-old Caucasian male patient was referred to the Department of Urology, Sapienza University of Rome, with gross hematuria and dysuria, in November 2014.

The patient’s personal history included heavy tobacco smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and psoriasis during the last 30 years. The patient also underwent open partial colon resection for diverticulitis, and right hip prosthesis treatment for ankylosing spondylitis.

A transabdominal ultrasound scan revealed a 3-cm mass of the left anterior wall of the bladder. A contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the presence of a 34×24 mm vegetative lesion of the bladder on the left lateral and anterior wall, with a normal bilateral upper urinary tract. The patient underwent cystoscopy and successive diagnostic transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT).

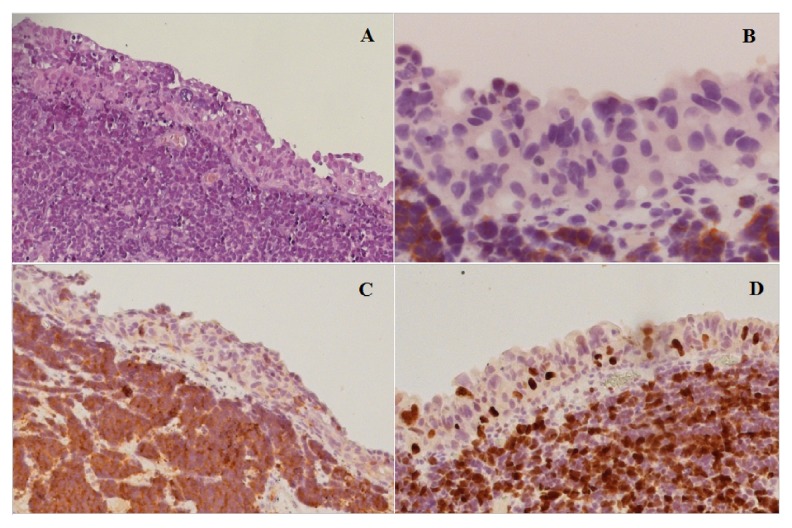

The pathological examination revealed a pT2 high-grade urothelial carcinoma, showing widespread neuroendocrine differentiation in more than 80% of cells (Figure 1A). The immunohistochemical staining of the specimen was positive for Synaptophysin (Syn) and Neurone-Specific Enolase (NSE) (Figure 1B, 1C), confirming the neuroendocrine origin of the tumor, while Chromogranin A (CgA) and Somatostatin staining were both negative. The proliferation index, evaluated with Ki-67, was 70% (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Histopathological examination of the neuroendocrine carcinoma after diagnostic TURB. (A) Neuroendocrine cancer cells are situated below the normal urothelium. Hematoxylin and eosin stain (H & E ×10). (B) The synaptophysin stain shows the strongly positive staining of neoplastic cells, suggestive of neuroendocrine differentiation (H & E ×10). (C) Neoplastic cells are positive for NSE confirming the neuroendocrine differentiation of tumor (EE, ×10). (D) Ki67 staining highlights the high mitotic index of the tumor cell population.

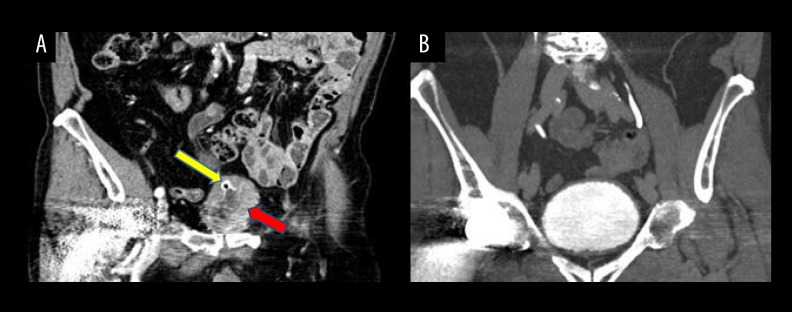

The patient was evaluated by a multidisciplinary team who decided to perform to a full-body CT scan to obtain a clinical staging of this rare disease. The CT scan (Figure 2A) showed that the bladder lesion had increased in volume, showing a diameter of 45 mm associated with a thickening of the left bladder wall. No suspicious lymph nodes or distant metastasis were revealed.

Figure 2.

CT scan with contrast images of the neuroendocrine carcinoma of the bladder. There are many CT artifacts due to the patient’s right hip prosthesis. Staging CT scan (venous phase) before neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed a vegetative lesion of the bladder (red arrow) associated with a thickening of the bladder wall (yellow arrow), and no suspicious lymph nodes or distant metastasis (A). CT scan (urography phase) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed complete disappearance of the bladder lesion and no evidence of distant metastasis (B).

Considering the patient age and comorbidities, a multidimensional geriatric assessment of the patient was performed to start chemotherapy treatment. The patient was evaluated to be suitable for a multimodal treatment of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin/etoposide every 21 days for 3 cycles. Cisplatin (CDDP) was administered at 75 mg/mq intravenously on day 1 of the 3-week cycle and etoposide (VP-16) at 100 mg/mq intravenously on days 1 to 3 every 3 weeks. The anti-blastic therapy was associated with granulocyte-colony stimulating factors (G-CSF) in primary prevention.

No high-level toxicity has been verified, except for a low-grade nephrotoxicity observed during the first cycle, anemia G1/G2 during the whole treatment, thrombocytopenia G1, and nausea G1.

A full-body CT scan performed at the end of treatment (Figure 2B) showed a complete disappearance of the vesical lesion previously described and no evidence of distant metastasis, while the evidence of a wall thickening of the bladder dome was related to the previous TURBT.

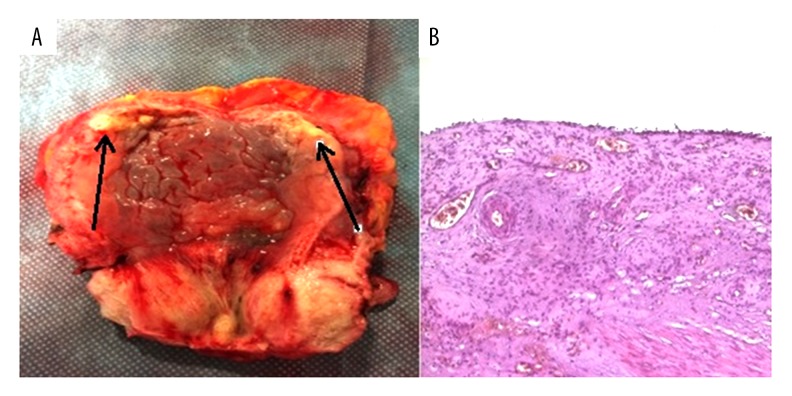

One month after the last cycle of chemotherapy, the patient underwent radical cystectomy and lymphadenectomy with the placement of bilateral ureterocutaneostomy (Figure 3A). Postoperative course was uneventful. Pathological examination of a bladder specimen revealed that there were no microscopic signs of tumor (ypT0) (Figure 3B) in the bladder or in any dissected lymph nodes, showing that a pathological complete response of the neuroendocrine tumor was obtained with the neoadjuvant performed chemotherapy. A full-body CT scan performed 1 month after surgery was completely negative for local and metastatic recurrence; therefore, a close follow-up and no adjuvant chemotherapy was planned. One year from diagnosis, the patient is still alive. A full-body CT scan on November 2015, 6 months after surgery, showed no evidence of local or metastatic disease.

Figure 3.

Macroscopic and microscopic evidence of complete remission after neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by cystectomy. (A) Surgical specimen of the bladder after cystectomy. No residual tumor tissue could be detected except for fibrotic areas (arrows). (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the neuroendocrine carcinoma after cystectomy post-neoadjuvant chemotherapy. There is no presence of tumor cells. The urothelium is absent or present single-layer without neoplastic issues (H & E, ×4).

Discussion

The literature contains many case reports and reviews of SCCUB, but few retrospective and prospective studies considering the different treatment approaches to improve the poor prognosis; such studies include local treatments such as radiotherapy and cystectomy alone, associated with poor outcomes [18], or combinations of radical surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. In the treatment of LD (≤cT1-4aN0M0), as in our clinical case, many clinical studies showed that combined strategies with chemotherapy resulted in better clinical response and/or in a pathologic downstaging of the disease compared with local strategies alone.

Multimodality therapies included neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystectomy [12,14], radical cystectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy [10] and sequential chemoradiation [8,19]. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, in particular, when compared with surgery alone [11,12,14,20] or adjuvant chemotherapy [14], gave the best results in improving the median overall survival (mOS).

One of the most important retrospective studies on the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy was conducted by Siefker-Radtke et al. [12]. In that trial the patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed a higher rate of 5-year disease-free survival than those who received cystectomy alone (78% vs. 36%, respectively). This encouraging result led to the first prospective clinical trial of SCCUB by the same authors [14], who conducted a phase II clinical trial on alternating doublet chemotherapy with ifosfamide/doxorubicin and etoposide/cisplatin as neoadjuvant treatment in surgically resectable SCCUB and palliative therapy in unresectable disease. The results confirmed the long-term survival with neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared to the metastatic chemotherapy (mOS of 58 months vs. 13.3 months, respectively). In the present case, the patient was treated with cisplatin and etoposide regimen. One year from diagnosis there is no evidence of recurrence disease. Other clinical trials confirmed the advantage, in terms of overall survival, of treating neuroendocrine bladder cancer with platinum-based chemotherapy [3,21,22].

Another important retrospective study was conducted by Lynch et al. [11], which reported that neoadjuvant treatment was associated with improved mOS and disease-specific survival (DSS) compared with cystectomy alone (mOS: 159.5 months vs. 18.3 months; 5-yr DSS: 79% vs. 20%). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy resulted also in a pathologic downstaging to ≤pT1N0 in 62% of tumors compared to 9% of patients treated with surgery alone.

Based on these data, many reviews and literature review updates [15,23] recommended neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery as the treatment of choice for surgically resectable SCCB, achieving a cure in 78–80% of the patients [23]. The rationale behind this approach relies on the rapid growth and upstaging after initial surgery [15]; the advantage of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the possibility to treat micrometastatic disease at an early stage and downstage the disease, facilitating radical surgery [23,24]. Sequential chemoradiotherapy is a second treatment option, especially for patients who are not eligible for surgery, achieving a cure in 36 to 70% of cases [19].

The 2013 Consensus guidelines from the Canadian Association of Genitourinary Medical Oncologists (CAGMO) by Moretto et al. [20] recommends treating LD SCCUB with neoadjuvant (Level 3, Grade C) or adjuvant chemotherapy (Level 4, Grade D) using the same platinum doublet regimens used for SCLC, by means of cisplatin and etoposide (Level 3, Grade C), followed by cystectomy or radiation in a bladder-sparing therapy (Level 3, Grade C).

The National Cancer Care Network (NCCN) guidelines are now the only guidelines that include SCCB. The 2015 NCCN guideline [25], in the section dedicated to non-urothelial carcinomas of the bladder, recommends that any small-cell component (or neuroendocrine features) should be treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by either cystectomy or radiation therapy, if there is no metastatic disease, recommending that primary chemotherapy regimens should be similar to that used in small cell lung cancer. The NCCN guidelines, in contrast to the CAGMO, reported that no data in the literature support the use of adjuvant chemotherapy in the management of nonurothelial carcinomas at any stage. Due to the lack of randomized controlled trials, there is no clear consensus on whether patients with LD should undergo radiotherapy or surgery after the initial chemotherapy.

On the basis of our literature review, we successfully treated our patient with LD SCCUB by means of neoadjuvant chemo-therapy based on cisplatin plus etoposide, and the complete response obtained confirms the role of neoadjuvant chemo-therapy in downstaging LD SCCUB before radical surgery and the efficacy of the neuroendocrine regimens used for SCLC in extrapulmonary NETs.

In the absence of a multi-institutional comparative trial, it is very difficult to establish authoritative treatment guidelines, and there is no definitive conclusion regarding the best multimodality therapy strategy for the different stages of SCCUB. However, the improved clinical outcomes found in the literature and the positive result obtained in the present case suggest the utility of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, especially the regimen of cisplatin plus etoposide in LD SCCUB.

Conclusions

Small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder is a rare and aggressive disease showing advanced stages at diagnosis and a poor prognosis. A standard treatment strategy is not yet established, but a multimodal treatment approach is the best option compared to local therapy alone. This case report is consistent with previously reported retrospective data demonstrating high response rate and downstaging with neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on cisplatin and etoposide protocol for LD SCUC. Multi-institutional and prospective studies are required to establish the standard treatment algorithm for SCUC, but considering the good results obtained, we highly recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy for the management of surgically resectable SCUC.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Source of support: La Sapienza University of Rome

References:

- 1.Galanis E, Frytak S, Lloyd RV. Extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:1729–36. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970501)79:9<1729::aid-cncr14>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shahab N. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma of the bladder. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:15–21. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bui M, Khalbuss WE. Primary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary bladder with coexisting high-grade urothelial carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Cytojournal. 2005;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koay EJ, Teh BS, Paulino AC, Butler EB. A surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of small cell carcinoma of the bladder: Epidemiology, prognostic variables, and treatment trends. Cancer. 2011;117:5325–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaggon JR, Brown TA, Mayhew R. Metastatic primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the genitourinary tract: A case report of an uncommon entity. Am J Case Rep. 2013;14:147–49. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.883908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okada A, Iida K, Hamakawa T. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the kidney and bladder with loss of heterozygosity and changes in chromosome 3 copy number. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:611–16. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.894274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer SF, Aikawa M, Cebelin M. Neurosecretory granules in small cell invasive carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Cancer. 1981;47(4):724–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810215)47:4<724::aid-cncr2820470417>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bex A, Nieuwenhuijzen JA, Kerst M, et al. Small cell carcinoma of bladder: A single-center prospective study of 25 cases treated in analogy to small cell lung cancer. Urology. 2005;65:295–99. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ismaili N, Heudel PE, Elkarak F, et al. Outcome of recurrent and metastatic small cell carcinoma of the bladder. BMC Urol. 2009;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quek ML, Nichols PW, Yamzon J, et al. Radical cystectomy for primary neuroendocrine tumors of the bladder: The university of southern california experience. J Urol. 2005;174(1):93–96. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000162085.20043.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lynch SP, Shen Y, Kamat A, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in small cell urothelial cancer improves pathologic downstaging and long-term outcomes: results from a retrospective study at the MD Anderson Cancer Center. Eur Urol. 2013;64(2):307–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siefker-Radtke AO, Dinney CP, Abrahams NA, et al. Evidence supporting preoperative chemotherapy for small cell carcinoma of the bladder: A retrospective review of the M. D. Anderson cancer experience. J Urol. 2004;172:481–84. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000132413.85866.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walther PJ. Adjuvant/neo-adjuvant etoposide/cisplatin and cystectomy for management of invasive small cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 2002;167:285. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siefker-Radtke AO, Kamat AM, Grossman HB, et al. Phase II clinical trial of neoadjuvant alternating doublet chemotherapy with ifosfamide/doxorubicin and etoposide/cisplatin in small-cell urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2592–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macedo LT, Ribeiro J, Curigliano G, et al. Multidisciplinary approach in the treatment of patients with small cell bladder carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37:558–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis MP, Murthy MS, Simon J, et al. Successful management of small cell carcinoma of the bladder with cisplatin and etoposide. J Urol. 1989;142:817. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38901-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strosberg JR, Coppola D, Klimstra DS, et al. The NANETS consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of poorly differentiated (high-grade) extrapulmonary neuroendocrine carcinomas. Pancreas. 2010;39(6):799–800. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ebb56f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng L, Pan CX, Yang XJ, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: A clinicopathologic analysis of 64 patients. Cancer. 2004;101:957–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bex A, de Vries R, Pos F, et al. Long-term survival after sequential chemo-radiation for limited disease small cell carcinoma of the bladder. World J Urol. 2009;27:101–6. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moretto P, Wood L, Emmenegger U, et al. Management of small cell carcinoma of the bladder: Consensus guidelines from the Canadian Association of Genitourinary Medical Oncologists (CAGMO) Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:E44–56. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choong NW, Quevedo JF, Kaur JS. Small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. The Mayo Clinic experience. Cancer. 2005;103(6):1172–78. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ismaili N, Arifi S, Flechon A, et al. Small cell cancer of the bladder: Pathology, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Bull Cancer. 2009;96(6):E30–44. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2009.0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismaili N. A rare bladder cancer-small cell carcinoma: review and update. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:75. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahsaini M, Riyach O, Tazi MF, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the urinary tract successfully managed with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Case Rep Urol. 2013;2013:598325. doi: 10.1155/2013/598325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Bladder Cancer. Version 2. 2015. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2015.