Key Clinical Message

Severe recessive mitochondrial myopathy caused by FBXL4 gene mutations may present prenatally with polyhydramnios and cerebellar hypoplasia. Characteristic dysmorphic features are: high and arched eyebrows, triangular face, a slight upslant of palpebral fissures, and a prominent pointed chin. Metabolic investigations invariably show increased serum lactate and pyruvate levels.

Keywords: Cerebellar atrophy, encephalomyopathy, FBXL4 gene, lactate, mitochondrial encephalopathy, polyhydramnios, pyruvate

What's already known about this topic?

Polyhydramnios can be a sign of underlying fetal metabolic disease

What does this study add?

Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy caused by compound heterozygous mutations in the FBXL4 gene, demonstrated by whole exome sequencing (WES), has never been previously described as cause of fetal anomalies and polyhydramnios.

Targeted exome sequencing proved to be successful in detecting the cause in a (postnatal) case of suspected mitochondrial disease.

Case Description

Polyhydramnios in the second and third trimester of pregnancy is defined by (semiquantative) measurements such as a maximum vertical pocket (MVP) >8 cm, or an amniotic fluid index (AFI) >24 cm. Approximately 90% of cases are idiopathic or caused by gestational diabetes (GDM) 1. However, 10% of cases are associated with fetal structural abnormalities 2. Most frequent causes are impaired swallowing from any cause (gastrointestinal, facial, musculoskeletal, or brain abnormalities), cardiac failure, hydrops, and renal abnormalities. Metabolic diseases, such as congenital disorders of glycogen storage, are also incidentally reported to present with polyhydramnios in pregnancy 3.

The usual diagnostic work‐up of polyhydramnios is to exclude GDM and maternal infections, and to perform an extensive structural assessment to rule out fetal anomalies. The presence of structural anomalies, involves increased risk of aneuploidy or other chromosomal and syndromic disorders. In isolated polyhydramnios, the risk of perinatal adverse outcome is, however, still increased when compared with uneventful pregnancies 4.

A 30‐year‐old primigravid woman, with a so far uneventful pregnancy, was referred to our clinic with polyhydramnios. Aside from a spontaneously closed ventricular septal defect (VSD) in her own infancy, both parents were healthy. A maternal uncle of the mother had died postnatally of an unknown cause.

First‐trimester combined test revealed a low risk for trisomies (NT 1.1 mm). The anomaly scan was performed at 20 weeks GA and showed no abnormalities. Transverse cerebellar diameter was normal at p50.

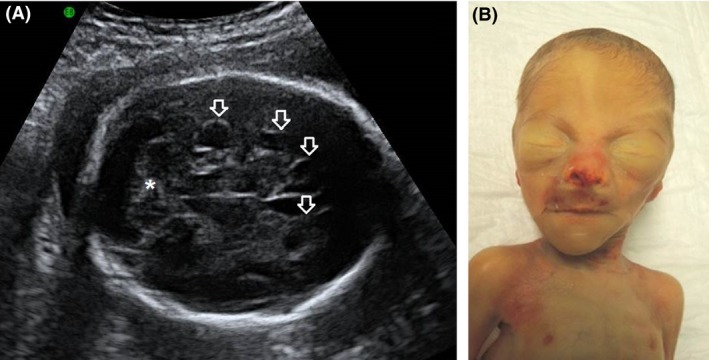

At 25 + 5 weeks of gestation, she presented with signs of polyhydramnios (uterine size that outpaced gestational age) and premature contractions. She received tocolytics and corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation. Ultrasound showed polyhydramnios (MVP 9.9 cm, AFI 27.5 cm) with normal fluid‐filled stomach and mild dilatation of both lateral ventricles (11 mm). Amniotic fluid drainage (1.8 L) was performed in an attempt to cease the premature contractions. More detailed fetal intracranial assessment was possible afterwards, showing an enlarged cisterna magna (12 mm) and a dysplastic and small cerebellum. The transcerebellar diameter measured 25.4 mm (slightly below p3, with head circumference p50, Fig. 1A). Further intracranial assessment was not possible due to maternal habitus, fetal position, and uterine contractions. The myocardium was hypertrophic with a small perimembraneous VSD. QF PCR and a CytoScan HD Array were performed, showing a small de novo duplication on chromosome 11 (11q22.1), including exon 1 of the contactine 5 (CNTN5) gene. This variant is not reported as genomic variant in the normal population, neither known to be associated with a genetic disorder or malformation. A relation with the clinical signs appears unlikely. Maternal serum infection testing (TORCHES) was also normal.

Figure 1.

(A) Fetal cerebral ultrasound at GA 25 + 5 showed cerebellar hypoplasia (*) and borderline dilatation of the ventricles. In retrospect, the outlines of some of the periventricular cysts are also discernible (see arrows). (B) shows the postmortem facial features. Note the prominent eyebrows and the triangular face with pointed chin. The bruises around the nose and philtrum, and the asymmetry of the nostrils are the effect of ventilation.

Two days later (26 + 0), she spontaneously delivered a boy of 835 g (−0.5 SDS), Apgar scores were 4/4/7 after 1.5 and 10 min, respectively. At birth, he was started on CPAP and transported to the neonatal intensive care unit. Physical examination showed a hypotonic infant with a lack of subcutaneous fat. The muscles and bones were clearly visible. He had mild dysmorphic features with high and arched eyebrows, a hairy forehead, triangular face, a slight upslant of palpebral fissures, down turned corners of the mouth, mild hypoplastic alae nasi, prominent pointed chin, deep incisura between tragus and antitragus providing a clear view into the external meatus (Fig. 1B). He had relatively long and slender arms and legs, large hands, long fingers, small fingernails and somewhat broad distal phalanges. The lower extremities showed bilateral pes cavus with broad metatarsals and prominent heels. Testes were not palpable in the scrotum. Postnatal cardiac ultrasound confirmed the presence of a small VSD. Cranial ultrasound on first postnatal day showed bilateral peri‐ and intraventricular hemorrhages with dilatation of the ventricles, periventricular pseudocysts, and confirmed the presence of cerebellar atrophy.

A few hours after birth, the neonate required mechanical ventilation and surfactant treatment for respiratory distress syndrome. He developed hypotension and was treated with fluid boluses and inotropic support and antibiotics. Despite stabilization of blood pressure and systemic circulation, he developed a progressive lactate acidosis with extremely high plasma lactate: 19.1 mmol/L [normal range 0.5–2.2] and high pyruvate: 269 μmol/L [normal range 40–140]. The L/P (lactate/pyruvate) ratio was 71, which is strongly increased (normal <20). Organic acid analysis in urine showed a strong increase of lactate (56540 μmol/mmol creatinine) and increases of 3‐OH‐butyrate, pyruvate, fumarate, malate, and 4‐OH‐phenyllactate. The amino acids proline and lysine were increased in both urine and plasma. Oligosaccharides in urine and acylcarnitines and very long‐chain fatty acids in plasma were normal. In the absence of secondary causes, these findings are consistent with primary lactic acidosis, caused by a disorder of the pyruvate metabolism or a mitochondrial respiratory chain defect.

Due to the severity of the cumulative problems, the neonate died 2 days after birth. Postmortem cranial MRI confirmed the findings on ultrasound, showing extensive bilateral intra‐ and periventricular hemorrhage with adjacent cyst (Figure S1C), vermian and cerebellar hypoplasia with a retrocerebellar pseudocyst (Figure S1D).

DNA analysis of the PDHA1‐gene (most frequent genetic cause of pyruvate‐dehydrogenase complex deficiency) showed no pathogenic mutations. Large deletions, point mutations, and small insertions/deletions in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) derived from blood were excluded by next‐generation sequencing (NGS) using the Illumina MiSeq platform and a dedicated bioinformatics pipeline (available on request).

For whole exome sequencing, exome enrichment was performed by the Agilent SureSelectXT exome enrichment kit version 4, including the UTR regions. Sequencing was performed by an Illumina HiSeq2000 (San Diego, CA) using a 2 × 100 bp paired‐end recipe. Basecalling, and demultiplexing was done using bcl2fastq 1.8.4.,(Illumina, San Diego, CA) reads were aligned onto the human reference genome (hg19) using BWA 0.5.9., duplicates marked using the PICARD software suite 1.77 (GitHub Enterprise, San Francisco, CA), and variants were called using GATK 2.1‐8. Annotations were added using an in‐house build annotation database, according to UCSC RefGene track, dbSNP137, and the dbNSFP (v2.0). Targeted exome analyses of a panel of 447 nuclear genes were performed, containing known mitochondrial disease genes and functionally or clinically related genes. Two heterozygous mutations in the FBXL4 gene were detected and confirmed by Sanger sequencing: c.292C>T (p.(Arg98*))and c.1303C>T (p.(Arg435*)). Both are nonsense mutations resulting in a premature stop codon at position p.98 and p.435 of the FBXL4 protein, respectively. The location of these mutations on different alleles (compound heterozygosity) was confirmed by testing the parents.

Missense and stop mutations in the FBXL4 gene were reported recently to be associated with severe autosomal recessively inherited mitochondrial encephalomyopathy 5, 6, 7, 8. Our case is the first case demonstrating a premature prenatal onset of symptoms of FBXL4‐related mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. The polyhydramnios was the primary sign, leading to the detection of brain abnormalities on more detailed fetal ultrasound examination. This early presentation of polyhydramnios is most likely caused by hypotonia and diminished fetal movements.

The cases of FBXL4‐related encephalopathy reported so far are characterized by increased serum lactate level, psychomotor delay, hypotonia, failure to thrive, swallowing difficulty, and muscle wasting 6. Onset of symptoms varied from neonatal onset after term birth, to the age of 14 months 5, 6, 8. Other reported cases were born at term or premature due to medical intervention for intrauterine growth retardation or reduced fetal movements 5, 6.

The FBXL4 gene is situated on nuclear DNA on chromosome 6q16.1. The FBXL4 mitochondrial protein contains an F‐box in its N‐terminal half, followed by 11 leucine‐rich repeats 9, and is expressed in heart, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, and placenta 10. Evidence of the pathogenetic effect of FBXL4 mutations was provided by skeletal muscle biopsies and fibroblasts showing defects in mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme activities, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, a disturbance of the dynamic mitochondrial network, and mtDNA depletion 5.

The nonsense mutation p.Arg435* in the FBXL4 gene, present in our patient, was earlier reported in homozygous form in a child of consanguineous parents with early onset mitochondrial encephalopathy, severe hypotonia, cardiomyopathy, MRI abnormalities, increased serum lactate, and premature death 5. The second mutation detected in our patient (p.Arg98* mutation) has not been reported previously. However, like the other mutation reported, this nonsense mutation leads to nonsense‐mediated decay (NMD, RNA degradation) or a truncated protein 5, 6. As a result, our patient would have been unable to produce a normal FBXL4 gene product.

The mother was pregnant again before exome sequencing had started. Within the prenatal timeframe, exome sequencing lead to the diagnosis of the first child, consequently enabling prenatal diagnosis for the second child. Amniocentesis with sequence analysis of the FBXL4 gene confirmed that the fetus was unaffected. The pregnancy resulted in the birth of a healthy child. The VSD in our patient is considered to be a separate finding (familial trait), which is not related to the syndrome.

Our case demonstrated a prenatal onset of mitochondrial encephalomyopathy presenting with polyhydramnios, causing premature delivery, and cerebellar atrophy. The neonate was hypotonic and in a poor condition with need for mechanical ventilation, inotropic support, and persistent lactate acidosis. Targeted exome sequencing using a mitochondrial gene panel proved its benefit by revealing compound heterozygous mutations in the FBXL4 gene. Prenatal testing was successfully carried out in the current pregnancy. Direct testing for mutations in the FBXL4 gene should be considered in patients with severe encephalomyopathy with high levels of serum lactate.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supporting information

Figure S1. C. shows an axial view of the postmortal MRI (T2‐weighted images) showing dilated ventricles with bilateral peri‐ and intraventricular hemorrhages and cysts adjacent to the right ventricle (arrows). D. shows the vermian and cerebellar hypoplasia with enlarged cisterna magna or pseudocyst (arrow).

Clinical Case Reports 2016; 4(4): 425–428

References

- 1. Harman, C. 2008. Amniotic fluid abnormalities. Semin. Perinatol. 32:288–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dashe, J. , McIntire D., Ramus R., Santos‐Ramos R., and Twickler D. M.. 2002. Hydramnios: anomaly prevalence and sonographic detection. Obstet. Gynecol. 100:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Raju, G. P. , Li H.‐C., Bali D., Chen Y. T., Urion D. K., Lidov H. G., et al. 2008. A case of congenital glycogen storage disease type IV with a novel GBE1 mutation. J. Child Neurol. 23:349–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Magann, E. , Chauhan S., Doherty D., Lutgendorf M. A., Magann M. I., Morrison J. C., et al. 2007. A review of idiopathic hydramnios and pregnancy outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 62:795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu P., Faqeih E. A., Al‐Asmari A. M., Saleh M. A., Eyaid W., Hadeel A., et al. 2013. Mutations in FBXL4 cause mitochondrial encephalopathy and a disorder of mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93:471–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gai, X. , Ghezzi D., Johnson M. A., Biagosch C. A., Shamseldin H. E., Haack T. B., et al. 2013. Mutations in FBXL4, Encoding a Mitochondrial Protein, Cause Early‐Onset Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93:482–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wortmann, S. , Koolen D., Smeitink J., van den Heuvel L., Rodenburg R. J., et al. 2015. Whole exome sequencing of suspected mitochondrial patients in clinical practice. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 38:437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huemer, M. , Karall D., Schossig A., Abdenur J. E., Al Jasmi F., Biagosch C., et al. 2015. Clinical, morphological, biochemical, imaging and outcome parameters in 21 individuals with mitochondrial maintenance defect related to FBXL4 mutations. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 38:905–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jin, J. , Cardozo T., Lovering R. C., Elledge S. J., Pagano M., Harper J. W., et al. 2004. Systematic analysis and nomenclature of mammalian F‐box proteins. Genes Dev. 18:2573–2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Winston, J. T. , Koepp D. M., Zhu C., Elledge S. J., Harper J. W.. et al. 1999. A family of mammalian F‐box proteins. Curr. Biol. 9:1180–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. C. shows an axial view of the postmortal MRI (T2‐weighted images) showing dilated ventricles with bilateral peri‐ and intraventricular hemorrhages and cysts adjacent to the right ventricle (arrows). D. shows the vermian and cerebellar hypoplasia with enlarged cisterna magna or pseudocyst (arrow).