Abstract

Studies show that limited functional recovery can be achieved by plasticity and adaptation of the remaining circuitry in partial injuries in the central nervous system, although the new circuits that arise in these contexts have not been clearly identified or characterized. We show here that synaptic contacts from dorsal root ganglions to a small number of dorsal column neurons, a caudal extension of nucleus gracilis, whose connections to the thalamus are spared in a precise cervical level 1 lesion, underwent remodeling over time. These connections support proprioceptive functional recovery in a conditioning lesion paradigm, as silencing or eliminating the remodelled circuit completely abolishes the recovered proprioceptive function of the hindlimb. Furthermore, we show that blocking repulsive Wnt signalling increases axon plasticity and synaptic connections that drive greater functional recovery.

In humans, limited functional recovery can be achieved through task-specific rehabilitation, without restoration of the original disrupted connections. The adaptability or plasticity of neural circuits has been proposed to serve as the underlying mechanism to spontaneous recovery1–8. Spontaneous formation of novel corticospinal connections on spared spinal circuits has been demonstrated to occur after spinal cord injury (SCI)6–8. In particular, recent studies propose that pharmacological and electrical stimulation of the spinal cord combined with robot-assisted rehabilitation can lead to greater recovery of motor functions in severely injured animals via a novel circuit relay in the absence of the direct repair of the severed longitudinal axons3. However, little work has been done to identify the relevant changes of the circuits that lead to functional recovery and how to enhance the circuit adaptation to improve the life quality of people who sustain SCI.

We establish a partial injury model in the high cervical level (C1) by severing the dorsal column, which carries proprioceptive somatosensory information to the brainstem nuclei in rats. This precise injury, via wire-knife, spares part of the connections between dorsal column neurons in the caudal portion of the gracile nucleus, and the thalamus. We observe that the synaptic connections between the proprioceptive sensory axons and these dorsal column neurons increase over time, accompanied by improved proprioceptive functions. To test whether this small number of neurons, only ~5% of nucleus gracilis neurons, can support functional recovery, we either silenced or severed the dorsal columns caudal to the injury and newly recovered proprioceptive function is lost. After SCI, multiple members of the Wnt glycoprotein family are expressed in the tissues surrounding the injury site-limiting axon plasticity9–12. We then blocked Wnt inhibition in our model to further enhance axon plasticity. We find that increased axon plasticity correlates with more synaptic connections between propriceptive neurons and the dorsal column neurons and more functional recovery, highlighting the functional relevance of the reorganized circuitry.

Results

C1 lesion disrupts proprioceptive input to nucleus gracilis

We lesioned the dorsal columns bilaterally at C1 to interrupt the vast majority of the flow of ascending proprioceptive input from lumbar dorsal root ganglia (DRG)13 1 week after peripheral conditioning of lumbar DRGs by chemically induced demyelination (manuscript in press 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.12.004). The lesion cavity was filled with either naive or secreted Frizzled-related peptide 2 (SFRP2)-secreting bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs). The lesion was kept as minimal as possible, while still being large enough to ensure complete transection of the sensory axons of the dorsal funiculi without significant injury to the corticospinal tract and other descending pathways in an effort to ensure that the observed behavioural deficits were because of the loss of proprioceptive input (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). Following 16 weeks of post-lesion behavioural testing, animals were labelled with bilateral fluorogold injection into the ventroposterolateral thalamic nucleus (VPL) and bilateral cholera toxin B (CTB) injection to the sciatic nerves13.

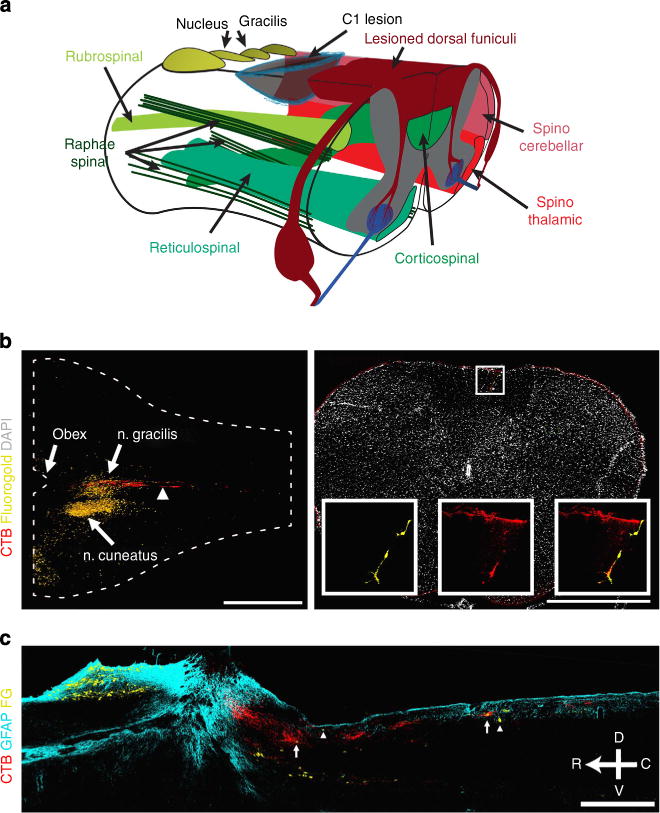

Figure 1. Cervical level 1 lesion of ascending dorsal column sensory axons.

(a) Illustration of the C1 dorsal column lesion to assess regeneration and functional recovery of ascending dorsal column axons. C1 lesion spares most other descending (green) and ascending (red) tracts including the internal arcuate fibres projecting from dorsal column nuclei to the thalamus. (b) Horizontal section of an intact spinal cord shows the location of the lesion (arrowhead) relative to the main body of nucleus gracilis. Transverse section of an intact spinal cord caudal to the site of injury demonstrates the presence of CTB-labelled puncta surrounding a VPL-projecting, fluorogold-labelled neuron in the dorsal column, enlarged in inset. (c) Saggital section of injured spinal cord illustrating CTB-labelled sensory axons (red) lesioned at C1 and fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons (yellow) with a few caudal to the lesion (arrowheads) and some innervated by CTB-labelled axons (arrows). CTB and fluorogold tracers were injected after C1 lesion to reveal the spared dorsal column neurons. Scale bar represents 1,000 μm (b) and 500 μm (c).

In intact animals, stereological counts revealed that 5.5±0.6% of all fluorogold-labelled, nucleus gracilis neurons were located within the dorsal columns at or caudal to the C1 location of SCI (Fig. 1). It is known that caudal to the main body of n. gracilis, sparse dorsal column neurons of n. gracilis and n. Bischoff, receive proprioceptive input from DRGs and project to VPL in the thalamus14–17. These neurons are distinct from the neurokinin-1-expressing neurons in fasciculus gracilis that are mainly located in the spinal enlargements, receive somatotopically restricted input from receptive fields in local dermatomes18,19. In this lesion paradigm, the axons of these dorsal column neurons to VPL are spared, although the projections into the main body of n. gracilis are all severed (Fig. 1).

Spared proprioceptive circuitry caudal to the injury persists

Stereological counting demonstrated a considerable and consistent reduction (>50%) in the number of VPL-projecting fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons caudal to the injury after dorsal column lesion, compared with intact animals (Dunnett’s P<0.05; n = 4 (intact), 5 (acutely injured, naive), 6 (SFRP2); Fig. 2). This reduction indicates that the injury either destroyed or severed the axons of more than half of these dorsal column neurons, the axons of which pass ventrally through the internal arcuate fibres. Between injured animals, there was no difference in the number of these fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons at either acute (5 days) or chronic (16 weeks) time points after injury (analysis of variance (ANOVA) P = 0.57; n = 5 (acutely injured, naive), 6 (SFRP2)), indicating that BMSC grafts did not affect survival of the caudal dorsal column neurons, which remain connected to the thalamus.

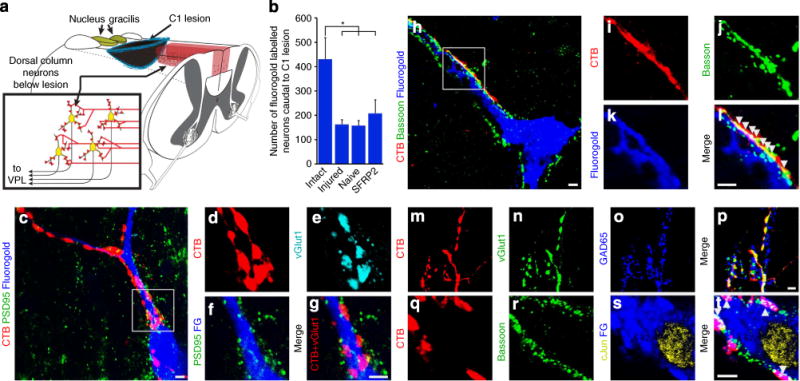

Figure 2. Proprioceptive axons terminate on dorsal column neurons caudal to the lesion.

(a) Illustration of dorsal column neurons caudal to the C1 dorsal column lesion that project ventrally through the internal arcuate fibres to nucleus VPL of the thalamus. Ascending dorsal column sensory axons labelled in red. (b) More than half of all dorsal column neurons below the lesion site have connections to VPL severed as determined by retrograde fluorogold labelling (Dunnett’s t-test *P<0.05). (c–g) Presynaptic vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta in proprioceptive axons labelled with CTB closely appose postsynaptic postsynaptic density protein 95 in fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons that project to VPL from below a C1 lesion. (h–l) CTB-labelled boutons colocalize with the presynaptic active zone protein bassoon upon fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons below a C1 lesion (arrowheads indicate CTB, bassoon overlap). (m–p) Presynaptic vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta in CTB-labelled axon terminals are contacted by GAD65-immunoreactive inhibitory puncta, indicating functional inhibitory feedback circuitry. (q–t) Postsynaptic fluorogold-labelled cells apposed by excitatory CTB-labelled synapses express the activity-dependent immediate early gene c-Jun (arrowheads indicate CTB, bassoon overlap). Scale bar represents 5 μm (c–t).

We examined the connectivity between primary proprioceptive neurons (labelled with CTB) and secondary, VPL-projecting dorsal column neurons labelled with fluorogold by, examining the distribution of synaptic markers. Proprioceptive axons make excitatory glutamatergic connections onto VPL-projecting dorsal column neurons in the spinal cord, similar to proprioceptive terminals in the main body of n. gracilis. In all groups, whether intact or injured, we observed evidence of functional innervation as there was direct apposition between presynaptic vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (vGlut1) in CTB-labelled boutons and postsynaptic density protein 95 in fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). Accordingly, these presynaptic, CTB-labelled terminals co-localized with the active zone protein bassoon directly juxtapose to fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta were also in close proximity to inhibitory GAD65-immunoreactive puncta, suggesting that these excitatory synapses receive inhibitory feedback and constitute a functional circuit (Fig. 2). Indeed, postsynaptic fluorogold-labelled cells apposed by excitatory CTB-labelled synapses expressed the activity-dependent immediate early gene c-Jun in all groups (Fig. 2).

Functional recovery after injury

Behaviour was examined using an accelerating rotarod, a beam-crossing task and a grid-crossing task, all of which require integration of information across sensory and motor circuitry. Rotarod balancing and beam-crossing are demanding tasks that require proprioceptive input and the ability of animals to perform these tasks after C1 lesion was essentially abolished (Fig. 3). Grid-crossing on an equally spaced wire grid is least dependent upon supraspinal control and was only mildly impaired by the C1 lesion (Fig. 3).

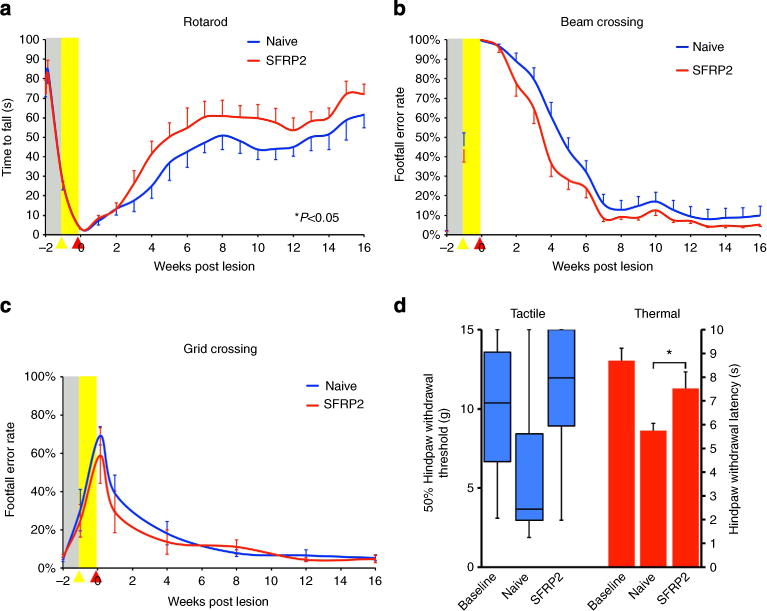

Figure 3. Functional recovery after SCI.

(a) Animals exhibited improved functional recovery on an accelerating rotarod when grafted with SFRP2-secreting BMSCs (repeated measures ANOVA P<0.05; n = 20 (naive), 21 (SFRP2)). (b) There was a mild, nonsignificant increase in the recovery of function in SFRP2–BMSC-grafted animals on the beam-crossing task (repeated measures ANOVA P = 0.08; n = 20 (naive), 21 (SFRP2)). (c) There were no differences in the recovery of function observed on the grid-crossing task, a behavioural test that is less dependent on proprioceptive feedback than rotarod or beam crossing, as central pattern generators can coordinate gross hindlimb coordination along the equally spaced grids (n = 5 (naive), 6 (SFRP2)). (d) Tactile responses measured bilaterally with calibrated Von Frey filaments and thermal responses measured bilaterally with a Hargreaves apparatus illustrate less thermal hypersensitivity in animals grafted with SFRP2–BMSCs (Hargreaves: two-tailed t-test *P<0.05; n = 5 (naive), 6 (SFRP2)). Baseline, pre-EtBr injection, levels shown with dashed line (grey box represents s.e.m.). Data presented as mean±s.e.m., except paw withdrawal thresholds, which are presented as the median and interquartile range.

All animals showed some recovery of function on the rotarod; however, those grafted with SFRP2-secreting BMSCs showed greater recovery of performance than control animals with 24% reaching pre-injury levels compared with 15% of naive grafted controls (repeated measures ANOVA P<0.05; n = 20 (naive), 21 (SFRP2); Fig. 3). On the beam-crossing task, naïve BMSC-grafted animals exhibited a mildly impaired, although not significantly different, recovery compared with SFRP2-secreting BMSC-grafted animals (repeated measures ANOVA P = 0.08; n = 20 (naive), 21 (SFRP2); Fig. 3). There was no difference in recovery from injury on the grid-crossing task, which is less likely to depend on proprioceptive input to the thalamus and more on intraspinal circuitry than the other behavioural tasks (n = 5 (naive), 6 (SFRP2); Fig. 3).

As SCI and aberrant plasticity after injury can lead to neuropathic pain states, we also tested animals for mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia. Mechanical sensation was tested bilaterally with calibrated Von Frey filaments at 16 weeks20. Naive BMSC-grafted animals did not exhibit any significant tactile allodynia compared with SFRP2–BMSC-grafted animals (Wilcoxon χ2 P = 0.13; n = 5 (naive), 6 (SFRP2); Fig. 3). Thermal sensitivity was tested at 16 weeks using a Hargreaves apparatus and SFRP2–BMSC-grafted animals showed significantly less thermal hypersensitivity than naive BMSC-grafted animals (two-way t-test P<0.05; n = 5 (naive), 6 (SFRP2); Fig. 3). SFRP2–BMSC-grafted animals were similar to baseline, pre-injury, levels on both Von Frey and Hargreaves tests, indicating that the induced plasticity produced no aberrant neuropathic pain states.

Remodelling of synaptic connections occurs caudal to the injury

We sought to determine whether axonal plasticity within the spared neural substrates of the spinal cord occurred following injury. In order to characterize the connectivity of synaptic boutons caudal to the lesion and the changes that occur in response to injury, we quantified CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta in intact animals, in acutely injured animals labelled immediately after C1 lesion and BMSC grafting, and in animals grafted with BMSCs, rehabilitated and labelled 16 weeks after injury.

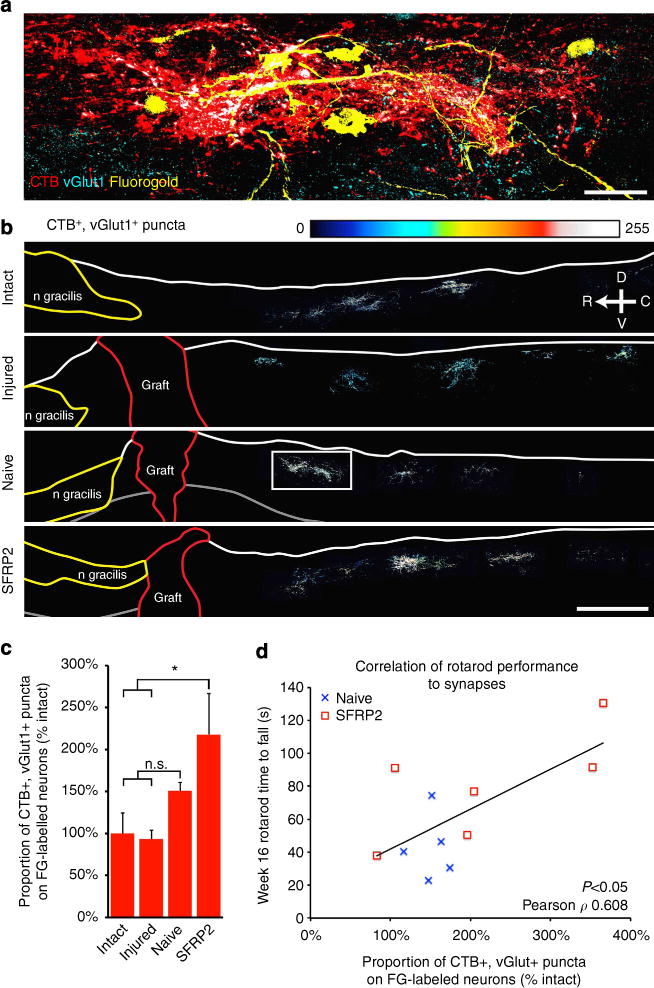

The total number of CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta (normalized to CTB labelling of dorsal column axons caudal to the injury) at 16 weeks post injury was similar, albeit slightly reduced, compared with intact and acutely injured animals: 78±25% of intact levels (naive), 84±22% (SFRP2) and 99±17% (acutely injured). However, when we examined the connections of those puncta, we found that immediately after injury, only 11±1% of CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta remained apposed to the fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons located in the white matter caudal to the injury. This was down from 28±1% in intact animals, likely because of the dramatic (>50%) reduction in fluorogold labelling of caudal dorsal column neurons projecting to VPL (Fig. 2). With the axonal plasticity induced by ethidium bromide (EtBr) injection and weekly behavioural testing, the percentage of CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta apposed to fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons increased moderately to 18±3% in control naive BMSC-grafted animals. However, SFRP2 promoted significant plasticity below the lesion with 26±5% of CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta directly apposed to fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons, similar to intact controls. Concurrent with the increased density of synaptic contacts on caudal dorsal column neurons, which remain connected to the thalamus, SFRP2-secreting BMSF grafts resulted in a larger proportion of fluorogold-labelled neurons abutted by CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive contacts (Dunnett’s P<0.05; Supplementary Fig. 3). It is likely that a greater proportion of CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta appose VPL-projecting neurons in all animals, but restricted uptake and the inability of fluorgold to fill all the dendritic arbors may result in fewer detected synapses.

As the proportion of CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta apposed to fluorogold increased after injury, the remaining fluorogold-labelled cells received a greater amount of input from lumbar DRGs (Fig. 4). The proportion of fluorogold-apposed puncta normalized to stereological counts of fluorgold-labelled dorsal column neurons caudal to the lesion in SFRP2-grafted animals was dramatically increased compared with acutely injured animals (Dunnett’s P<0.05) and intact control animals at 16 weeks after injury (ANOVA P<0.05, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc t-test P<0.05; n = 4 naive), (intact), n = 5 injured, 6 (SFRP2)). Furthermore, among all animals at 16 weeks post injury, rotarod performance correlated with the proportion of CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta apposed to fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons (normalized to stereological fluorogold neuron counts, Pearson correlation coefficient 0.608, bivariate ANOVA P<0.05; n = 5 (naive), 6 (SFRP2); Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Proprioceptive circuit plasticity on spared dorsal column neurons.

(a) CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta (white) contact fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons caudal to the C1 lesion (box in b). (b) Heat maps of vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta in CTB-labelled axon bouton-like structures. BMSC grafts are traced in red and the main body of n. gracilis in yellow. (c) The proportion of CTB-labelled vGlut1-immunoreactive puncta directly apposed to FG-labelled neurons, adjusted for the number of remaining FG-labelled neurons (stereological counts), was significantly increased in SFRP2–BMSC-grafted animals compared with acutely injured controls (Dunnett’s t-test, *P<0.05) and intact animals (Bonferroni-corrected post hoc t-test, *P<0.05). (d) Rotarod performance at week 16 correlates with an increase in CTB-labelled synapses on FG-labelled neurons (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.608, bivariate ANOVA P<0.05). Data presented as mean±s.e.m. Scale bars represent 500 μm; n = 4 (intact), 5 (acutely injured, naive) and 6 (SFRP2).

Increased synaptic connectivity due to sensory axon plasticity

Using our conditioning lesion paradigm by injecting trace amount of EtBr, proprioceptive axon plasticity is greatly increased, resulting in greater extent of regeneration than sciatic nerve crush (manuscript in press, 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014. 12.004). As SFRP2-secreting BMSC grafts increased the proportion of sensory axon terminals on spared dorsal column neurons and lead to more functional recovery, we sought to determine whether this circuit plasticity was further potentiated by a general growth-promoting effect of SFRP2 on primary sensory axons.

Peripheral conditioning by sciatic nerve crush induces the expression of Wnt receptors Frizzled2 and the atypical protein kinase Ryk in proprioceptive neurons, which limits proprioceptive regeneration after SCI12. We found that demyelination with EtBr likewise resulted in Ryk upregulation. Animals given unilateral sciatic nerve injections of EtBr with contralateral PBS control show increased expression of the repulsive Wnt receptor Ryk in both the demyelinated nerve and the ipsilateral dorsal column at 1 week after a C4 lesion, 2 weeks after the preceding sciatic injections (one-way paired t-test P<0.05; n = 3; Supplementary Fig. 4).

We found that blocking Wnt inhibition with SFRP2 further increased the regeneration induced by peripheral demyelination. SFRP2-secreting BMSC grafts increased the regeneration of CTB-labelled dorsal column axons 2.5-fold over control naive BMSCs (ANOVA P<0.05, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc t-test P<0.05, Supplementary Fig. 4). Despite the extensive axon plasticity promoted by SFRP2-secreting grafts, axons appeared to lack directional guidance and no regeneration beyond the lesion and into the main body of the de-afferented n. gracilis occurred. Lesion volumes were similar between groups and no correlation was found between lesion volume and behavioural recovery (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Remodelled circuitry is required for proprioceptive function

In order to directly assess the role of circuit adaptation in the observed recovery of behavioural function, we interrupted the function of remaining lumbar proprioceptive circuitry through both pharmacological and physical means. After 16 weeks of behavioural testing and recovery, animals not used for histology were randomly assigned for treatment with either the sodium channel blocker lidocaine (400 mg ml−1) in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF), or ACSF alone. We found that transiently silencing the dorsal columns at T10 with lidocaine injection eliminated the animals’ abilities to perform the rotarod task, independent of whether grafted with naive or SFRP2-secreting BMSCs (Fig. 5). The effects of lidocaine were dramatically more severe than control surgeries with ACSF injection and the animals recovered rotarod abilities over the course of an hour after injection (repeated measures ANOVA P<0.0005; n = 7 (ACSF: naive, SFRP2), 8 (lidocaine: naive, SFRP2); Fig. 5). There was no permanent deficit induced by lidocaine injection as animals performed at 94±8% of pre-injection levels 3 days after injection.

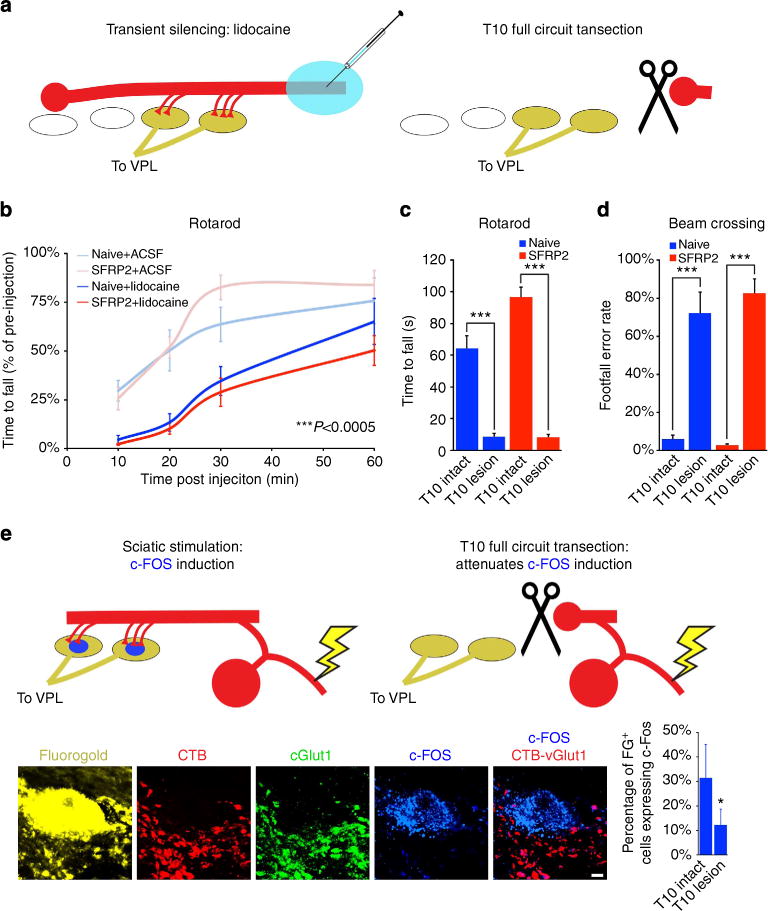

Figure 5. Circuit adaptation caudal to the lesion is required for functional recovery.

(a,b) Injection of lidocaine into fasciculus gracilis at T10 transiently silences and impairs functional recovery on accelerating rotarod, with substantial recovery by 1 h (repeated measures ANOVA P<0.0005; n = 7 (ACSF: naive, SFRP2) and 8 (lidocaine: naive, SFRP2)). (a) Physical transection of fasciculus gracilis at spinal level T10 eliminates behavioural recovery on (c) accelerating rotarod (ANOVA P<0.0005, Bonferroni-corrected post hoc t-test ***P<0.0005) and (d) beam-crossing (ANOVA P<0.0001; n = 7 (intact: naive, SFRP2) and 8 (T10 lesion: naive, SFRP2)). (e) Fluorogold-labeled neurons caudal to a C1 lesion in an animal intact at T10 express c-Fos when the sciatic nerve is stimulated. c-Fos induction sciatic stimulation is significantly reduced following lesion of fasciculus gracilis at spinal level T10 (two-tailed t-test, *P<0.05; n = 13 (intact) and 16 (T10 lesioned)). Data presented as mean±s.e.m. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

One week after transient silencing experiments, the animals were again randomly assigned, this time for either T10 dorsal column lesion, or sham control surgery. Following recovery from surgery, all animals with a second T10 lesion to the ascending proprioceptive axons were equally impaired on the rotarod (ANOVA P<0.0005) and beam crossing (ANOVA P<0.0001; n = 7 (intact: naive, SFRP2), 8 (T10 lesion: naive, SFRP2); Fig. 5). Importantly, animals subject to T10 lesion showed no disruption of the descending corticospinal tract (Supplementary Fig. 1). In addition, in animals subjected to a second injury at T10, electrophysiological stimulation of the sciatic nerve (0.1 ms duration, 2 V biphasic pulses, 1 h at 1 Hz) after T10 injury resulted in significantly reduced c-Fos expression in fluorogold-labelled dorsal column neurons caudal to the original C1 lesion (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Plasticity and adaptation of spared neural circuits after injury have been proposed to be a mechanism for mediating functional recovery for several decades6. However, very little work has been carried out to clearly identify the changes of connections or the creation of the new circuits that may underlie functional recovery. Understanding the neural circuit mechanism of functional adaption will allow us to understand the extent and limitation of circuit plasticity and to eventually properly and efficiently repair damaged circuits in the central nervous system. In this study, we focused on plasticity of somatosensory axons of the ascending dorsal funiculus, a compact, fasciculated tract with stereotyped connectivity that is readily amenable to experimental manipulation. Utilizing molecular, behavioural and electrophysiological means, we demonstrated that the synaptic connections between the proprioceptive axons and the dorsal column neurons are strengthened and the reorganized connections underlie functional recovery.

In order to generate novel synaptic contacts with spared dorsal column neurons, injured sensory axons need to be both more plastic in their response to injury and less likely to retract from the injury site. We induced plasticity through peripheral conditioning; however, Wnt induction at the injury site both limits plasticity and induces retraction of peripherally conditioned axons12. Attenuation of inhibitory Wnt signalling with SFRP2 promoted a greater number of novel connections, perhaps at the expense of existing synapses whose targets had been axotomized by the C1 injury. SFRP2-secreting grafts promoted significant axonal plasticity and synaptic reorganization, which, in turn, drove more behavioural recovery and electrophysiological function.

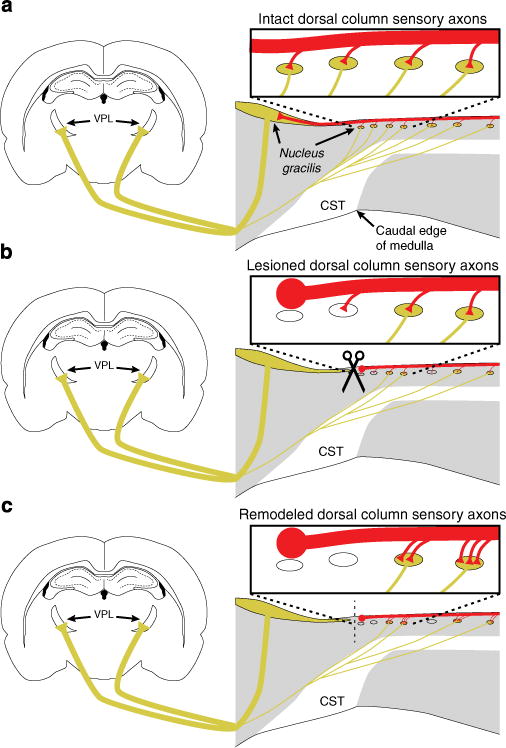

After partial SCI, spontaneous functional recovery is dependent not only upon the plasticity of injured axons, as measured by regeneration or sprouting, but by remodelling or recapitulation of interrupted circuitry. Regeneration of circuits after injury is one potential approach to repair circuitry; however, novel relay formation from either grafted cells21 or spared neural substrates3 has also proven to be a viable method for driving functional recovery. We show here that only a small fraction of intact neural substrate (≤5.5%) can be rewired and drive a sufficient level of functional recovery to reach pre-injury performance (Fig. 6). We demonstrated the necessity of the remodelled circuit in mediating functional recovery via transient pharmacological silencing as well as physical transection. While we cannot exclude that lidocaine injection could have impaired conduction of descending corticospinal axons in the rats we tested, the corticospinal-mediated component of the recovered behaviour would be expected to be quite minimal as targeted lesions of the corticospinal tract have been shown to produce only mild effects on gross hindlimb locomotor function22,23. In addition, the transient behavioural deficits induced by lidocaine injection were mimicked by a secondary lesion at T10 that spared the corticospinal tract. Future studies will be directed to understand how rewiring of this small group of neurons provide sufficient proprioceptive information to allow functional improvement.

Figure 6. Proprioceptive circuit recovery is driven by plasticity of primary sensory axons on spared dorsal column substrates.

(a) Primary sensory axons (red) synapse on dorsal column neurons that project to thalamic nucleus VPL (yellow). (b) After injury, the main body of nucleus gracilis is de-afferented and nearly half of dorsal column neurons caudal to the lesion are lost or axotomized. (c) Primary sensory axons establish de novo connections with the remaining neural architecture caudal to the injury. This plasticity of connectivity drives recovery of behavioural function and is enhanced by blocking inhibitory Wnt signalling.

In humans, SCI is often incomplete and the amount of spared neural substrate determines the extent of recovery from injury24–26. When it does occur, the majority of spontaneous functional recovery in humans and non-human primates after SCI occurs within 3–6 months after injury and continues up to 18 months in humans4,5. In a similar manner to the circuit adaptation we observe here in rodents, functional recovery in primates is likely driven by plasticity of spared circuitry that occurs during this critical window after injury5. Molecular modulation of Wnt pathways is an attractive therapeutic target after SCI as Wnts are able to regulate axon guidance, axon terminal formation and synaptogenesis27. Wnts act as guidance molecules for both descending supraspinal (corticospinal and raphaespinal) and ascending sensory axons28–30, and we have previously demonstrated that endogenously or exogenously applied Wnts mediate a remarkable inhibition of axon regeneration of both ascending and descending pathways in the dorsal funiculus9,12. It has not previously been demonstrated that manipulation of Wnt signalling can lead to any functional improvement of the somatosensory system. Here we show that molecular inhibition of Wnt signalling with SFRP2 is able to further augment even the robust recovery driven by peripheral conditioning and rehabilitation through increasing axonal plasticity and circuit remodelling. The molecular approaches that we have described can be used in combination with other therapies, including assisted rehabilitation, to promote functional recovery.

Methods

All animal work in this research was approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Group sample sizes were chosen based on previous studies and power analysis. One animal was excluded from the study because of evidence of incomplete C1 lesion with labelled sensory axons present in the main body of n. gracilis.

Isolation and transduction of syngeneic BMSCs

Primary BMSCs were isolated, cultured and transduced with retrovirus encoding haemagglutinin-tagged SFRP2 as described previously12. Before transplantation, BMSCs were cultured in standard media for 48 h, trypsinized (0.05% vol per vol) and resuspended in PBS at 100,000 cells per microlitre.

Surgical procedures

Sciatic nerve injection

Adult female Fischer 344 rats (120–135 g) were anaesthetized with isoflurane, and an area over the hindlimb was shaved and cleaned with povidone–iodine before an incision is made caudal and parallel to the femur. The sciatic nerve was exposed and injected with 2 μl (1 μl per branch) of 0.1% EtBr in PBS or PBS alone. Injections were made with a 36-ga NanoFil needle (World Precision Instruments Inc., Sarasota, FL) at a rate of 2 μl min−1 and the needle was held in place for an additional 10 s following injection.

C4 dorsal column lesion

Animals were deeply anaesthetized with 2 ml kg−1 of ketamine cocktail (25 mg ml−1 ketamine, 1.3 mg ml−1 xylazine and 0.25 mg ml−1 acepromazine). Spinal level C4 was exposed by laminectomy and the dura was punctured over the dorsal horn, ~1.2 mm lateral to midline. A Scouten wire-knife (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) was lowered to a depth of 1 mm from the surface of the spinal cord and extruded in an arc 2.5 mm wide and 1 mm deep. The dorsal columns were lesioned with two passes of the wire-knife and the intact dura was pressed against the wire edge of the lifted wire-knife to ensure complete transection of ascending dorsal column sensory axons. The lesion cavity was filled with ~200,000 BMSCs suspended in PBS, injected using glass micropipettes connected to a picospritzer (General Valve, Fairfield, NJ). The dorsal musculature was sutured with 4-0 silk sutures and the skin was closed with surgical staples.

C1 dorsal column lesion

Two separate cohorts of animals (11 and 30 individuals) were tested in these experiments. The group of 11 was food-restricted for testing on the grid-crossing task in addition to the beam-crossing task and rotarod (as described below). These 11 animals were also utilized for tracer injections and histology as described below. The animals were deeply anaesthetized with ketamine cocktail, and C1 vertebrae were removed by laminectomy. Connective tissue was gently removed over cisterna magna to render the brainstem and spinal cord visible. The dura was punctured above the fourth ventricle to allow the dura to lay flat over brainstem, and punctured again at 1.5 mm caudal to the obex and 1.25 mm lateral to midline. Lesions were made with a Scouten wire-knife extending in an arc 2.5 mm wide and 1 mm deep. As above, the dorsal columns were lesioned with two passes of the wire-knife and the intact dura was pressed against the wire edge of the lifted wire-knife to ensure complete transection of ascending dorsal column sensory axons. The lesion cavity was filled with ~200,000 BMSCs suspended in PBS, injected using glass micropipettes connected to a picospritzer.

T10 lidocaine injection

Animals were anaesthetized with isoflurane and a partial laminectomy of the T9 vertebrae was performed to expose spinal level T10. Animals were injected bilaterally with 1 μl lidocaine-HCl (400 mg ml−1, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in ACSF or ACSF alone split between two sites, 250 μm deep in the dorsal funiculus. The dorsal musculature was sutured with 4-0 silk sutures and the skin was closed with surgical staples. The animals were tested on an accelerating rotarod starting at 10 min after injection.

T10 dorsal column lesion

The animals were deeply anaesthetized with ketamine cocktail and T10 was exposed at the previous site of T9 laminectomy. The dura was punctured ~0.9 mm lateral to midline. Lesions were made with a Scouten wire-knife extending in an arc 1.8 mm wide and 1 mm deep. The dorsal columns were lesioned with two passes of the wire-knife as above to ensure complete transection of ascending dorsal column sensory axons. The animals were tested on accelerating rotarod and beam crossing after T10 lesion at 1 day or 1 week, respectively.

Tracer injection

Five days before being killed, the animals were injected into the sciatic nerve (11 bilaterally, 30 unilaterally) with a 1% wt per vol solution of the transganglionic tracer CTB (List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) using a 36-ga NanoFil syringe. The sciatic nerve was exposed as described above and 1 μl was injected into each the tibial and common peroneal branches bilaterally (4 μl total). During the same surgical session, animals were injected into VPL (11 bilaterally, 30 unilaterally) with 1 μl of 4% wt/vol solution of fluorogold (hydroxystilbamidine, methanesulfonate; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) in 12 sites bilaterally as previously described13.

Sciatic nerve stimulation

Thirty animals underwent unilateral sciatic nerve stimulation with a SD9 square pulse stimulator (Grass Technologies, Warwick, RI) 1 week after T10 dorsal column lesion or sham operation. The sciatic nerve was exposed as described above. Hook electrodes were used to deliver 0.1-ms-duration biphasic 2 V pulses for 1 h at 10 Hz. The animals were killed 1 h after stimulation.

Killing and tissue processing

Animals were deeply anaesthetized with ketamine cocktail and transcardially perfused with ice-cold PBS followed by 4% wt per vol paraformaldehyde in PBS. Spinal columns, sciatic nerves and DRGs were post-fixed overnight at 4 °C in 4% wt per vol paraformaldehyde. Tissue was transferred to 30% wt per vol sucrose in PBS for cryoprotection and sectioned on a cryostat (Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) at 20 mμ (horizontal spinal cord sections) and mounted directly on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Grafted spinal cords were sectioned sagittally at 40-μm thick and collected as free-floating sections. Sections were washed three times with PBS, blocked for 1 h in PBS with 0.25% triton-X100 (PBST) and 5% donkey serum, and then incubated overnight (except where noted below) at 4 °C with primary antibodies in PBST plus 5% donkey serum. On the second day of staining, sections were washed three times, incubated with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for two and a half hours at room temperature, counterstained with DAPI (1 μg ml−1; Sigma-Aldrich) and washed three final times in PBS. Antibodies used for fluorescent immunohistochemistry were as follows: rabbit anti-Ryk (1:250)29, goat anti-CTB (1:10,000; 3-day incubation; List Biological Laboratories), monoclonal N52 anti-neurofilament 200 kD (1:500; Sigma-Aldrich), guinea pig anti-vGlut1 (1:1,000) and rabbit anti-fluorogold (1:2,000; Millipore, Billerica, MA), rabbit anti-GFAP (1:750; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), monoclonal 6G6-1C9 anti-PSD95 (1:100; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL), rabbit anti-c-Jun (1:100; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), monoclonal 219E1 anti-bassoon (Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany), monoclonal GAD-6 anti-GAD65 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA), rabbit anti-c-Fos (1:100; AbCam, Cambridge, MA).

Image acquisition and analysis

Images were acquired on an inverted Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope with the LSM acquisition software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC, Thornwood, NY). Image density quantification was carried out on thresholded images using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Statistical tests indicated in main text were performed using the JMP 9 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). An investigator blinded to the experimental group performed all analyses.

Quantification and normalization of data

Stereological counts of fluorogold-labelled neurons in the dorsal columns (not grey matter) caudal to the injury site were made in every seventh 40-μm saggital section using the optical fractionator workflow in StereoInvestigator (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT). All synapse data described were acquired in the dorsal columns (not in grey matter) caudal to the injury site. CTB-vGlut1-labelled puncta apposed to fluorogold caudal to the injury site were taken as a percentage of total CTB-vGlut1-labelled puncta caudal to the injury site. This percentage was normalized to stereological counts of fluorogold-labelled neurons within the dorsal columns caudal to the injury site to yield the proportion of CTB-vGlut1 puncta apposing fluorogold-labelled neurons relative to intact control animals. For regenerating axon profiles within the entire volume of the graft, the total number of distinct axon profiles in every seventh 40-μm saggital section was counted and normalized to the total number of CTB-labelled axons within the dorsal columns caudal to the injury in those sections; data were presented relative to control. Lesion volume was calculated using the Cavalieri estimator tool in StereoInvestigator on every seventh 40-μm saggital section.

Behavioural testing

Two separate cohorts of animals (11 and 30 individuals) were tested in these experiments. All animals were trained on accelerating rotarod (5 r.p.m. initial, 45 r.p.m. max, 300 s max; Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) and beam crossing (1 inch diameter, 60 inch span, three passages per trial) for 2 weeks before bilateral sciatic injection of 0.1% wt per vol EtBr. Eleven animals were food-restricted and tested on grid-crossing (1 inch spaced wire grid, 60 inch span, three passages per trial) in addition to rotarod and beam crossing. All animals were tested before C1 lesion and weekly for 16 weeks after SCI by investigators blind to the experimental groups.

Eleven animals were tested for allodynia and hyperalgesia as follows: hindpaw 50% withdrawal threshold was assessed bilaterally using a series of calibrated von Frey filaments (Kom Kare, Middletown, OH, USA) using the up–down method exactly as described elsewhere20,31. Thermal withdrawal latency was assessed bilaterally using a Hargreaves apparatus (UARDG, Department of Anesthesiology, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA). Rats were acclimated in individual acrylic chambers on a glass surface that was maintained at 30 °C, before testing at a heating rate of 1 °C s−1 with a maximal cutoff at 20 s. After an initial acclimation measurement, the median of three subsequent measurements was taken as the thermal response latency for that paw, and the mean of values of both paws was used to represent each animal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NINDS RO1 NS47484, Wings for Life Foundation and Roman Reed foundation to Y.Z., Craig H. Neilsen Foundation Fellowship to E.R.H., as well as NIDDK R01 DK57629 to N.A.C. Y.Z., E.R.H. and N.A.C. designed experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. E.R.H., N.I., M.P. and C.A.L.-K. performed lesion and behavioural experiments and analysed data. K.T. processed tissue and performed histology. Y.Z. supervised the entire study and coordinated collaborations.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Y.Z., E.R.H. and N.A.C. designed the experiments and wrote the paper. E.R.H., N.I., M.P., K.T. and C.A.L.-K. performed the experiments and analysed results with Y.Z. and N.A.C.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at http://www.nature.com/naturecommunications

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permission information is available online at http://npg.nature.com/reprintsandpermissions/

References

- 1.Roy RR, Harkema SJ, Edgerton VR. Basic concepts of activity-based interventions for improved recovery of motor function after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1487–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrière G, Leblond H, Provencher J, Rossignol S. Prominent role of the spinal central pattern generator in the recovery of locomotion after partial spinal cord injuries. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3976–3987. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5692-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van den Brand R, et al. Restoring voluntary control of locomotion after paralyzing spinal cord injury. Science. 2012;336:1182–1185. doi: 10.1126/science.1217416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fawcett JW, et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord. 2006;45:190–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenzweig ES, et al. Extensive spontaneous plasticity of corticospinal projections after primate spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1505–1510. doi: 10.1038/nn.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bareyre FM, et al. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nn1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtine G, et al. Recovery of supraspinal control of stepping via indirect propriospinal relay connections after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2008;14:69–74. doi: 10.1038/nm1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueno M, Hayano Y, Nakagawa H, Yamashita T. Intraspinal rewiring of the corticospinal tract requires target-derived brain-derived neurotrophic factor and compensates lost function after brain injury. Brain. 2012;135:1253–1267. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, et al. Repulsive Wnt signaling inhibits axon regeneration after CNS injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8376–8382. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1939-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyashita T, et al. Wnt-Ryk signaling mediates axon growth inhibition and limits functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:955–964. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollis ER, II, Zou Y. Expression of the Wnt signaling system in central nervous system axon guidance and regeneration. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:5. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hollis ER, II, Zou Y. Reinduced Wnt signaling limits regenerative potential of sensory axons in the spinal cord following conditioning lesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:14663–14668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206218109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alto LT, et al. Chemotropic guidance facilitates axonal regeneration into brainstem targets and synapse formation after spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1106–1113. doi: 10.1038/nn.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bermejo PE, Jiménez CE, Torres CV, Avendaño C. Quantitative stereological evaluation of the gracile and cuneate nuclei and their projection neurons in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2003;463:419–433. doi: 10.1002/cne.10747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemplay S, Webster KE. A quantitative study of the projections of the gracile, cuneate and trigeminal nuclei and of the medullary reticular formation to the thalamus in the rat. Neuroscience. 1989;32:153–167. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kemplay SK, Webster KE. A qualitative and quantitative analysis of the distributions of cells in the spinal cord and spinomedullary junction projecting to the thalamus of the rat. Neuroscience. 1986;17:769–789. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wree A, Itzev DE, Schmitt O, Usunoff KG. Neurons in the dorsal column nuclei of the rat emit a moderate projection to the ipsilateral ventrobasal thalamus. Anat Embryol. 2005;210:155–162. doi: 10.1007/s00429-005-0012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramer MS. Anatomical and functional characterization of neuropil in the gracile fasciculus. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:283–296. doi: 10.1002/cne.21785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbadie C, Skinner K, Mitrovic I, Basbaum AI. Neurons in the dorsal column white matter of the spinal cord: complex neuropil in an unexpected location. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:260–265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu P, et al. Long-distance growth and connectivity of neural stem cells after severe spinal cord injury. Cell. 2012;150:1264–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metz GAS, Dietz V, Schwab ME, van de Meent H. The effects of unilateral pyramidal tract section on hindlimb motor performance in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 1998;96:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muir GD, Whishaw IQ. Complete locomotor recovery following corticospinal tract lesions: measurement of ground reaction forces during overground locomotion in rats. Behav Brain Res. 1999;103:45–53. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basso DM, Beattie MS, Bresnahan JC. Graded histological and locomotor outcomes after spinal cord contusion using the NYU weight-drop device versus transection. Exp Neurol. 1996;139:244–256. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bishop B. Neural plasticity. Part 4. Lesion-induced reorganization of the CNS: recovery phenomena. Phys Ther. 1982;62:1442–1451. doi: 10.1093/ptj/62.10.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Little JW, Ditunno JF, Stiens SA, Harris RM. Incomplete spinal cord injury: neuronal mechanisms of motor recovery and hyperreflexia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:587–599. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salinas PC. Wnt signaling in the vertebrate central nervous system: from axon guidance to synaptic function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenstermaker AG, et al. Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling controls the anterior-posterior organization of monoaminergic axons in the brainstem. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16053–16064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4508-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu Y, et al. Ryk-mediated Wnt repulsion regulates posterior-directed growth of corticospinal tract. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1151–1159. doi: 10.1038/nn1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyuksyutova AI, et al. Anterior-posterior guidance of commissural axons by Wnt-Frizzled Signaling. Science. 2003;302:1984–1988. doi: 10.1126/science.1089610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calcutt N. In: Pain Research. Luo ZD, editor. Vol. 99. Humana Press; 2004. pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.