Abstract

This paper considers the ways in which established criminological theories born and nurtured in the West might need to be transformed to be applicable to the context of East Asian societies. The analyses focus on two theoretical perspectives—Situational Action Theory and Institutional Anomie Theory—that are located at opposite ends of the continuum with respect to levels of analysis. I argue that the accumulated evidence from cross-cultural psychology and criminological research in East Asian societies raises serious questions about the feasibility of simply transporting these perspectives from the West to the East. Instead, my analyses suggest that the formulation of theoretical explanations of crime that are truly universal will require criminologists to create and incorporate new concepts that are more faithful to the social realities of non-Western societies, societies such as those in East Asia and Asia more generally.

Keywords: Comparative criminology, East Asia, Situational Action Theory, Institutional Anomie Theory

Introduction

In one of the Presidential Panels at the 2013 annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology, Charles Tittle (2013) posed the question: “Does criminology need international research?” His answer to his own question was an emphatic “yes.” Tittle emphasized that any genuine “theoretical science” must aspire to explain crime-relevant phenomenon, and such explanation requires the formulation of general theories. Moreover, general theories should ideally have universal applicability and be capable of being verified in a wide range of circumstances. Echoing an observation made by other advocates of comparative social science (Bennett 1980; Kohn 1987), Tittle pointed to an additional benefit of international research for the discipline, beyond that of simply assessing the extent to which theories prove to be universally applicable. He noted that efforts to apply theories in different contexts often provide the “inputs” that stimulate modifications of theories previously thought to have universal applicability.

The theme of the 6th annual conference of the Asian Criminological society—“Advancing Criminological and Criminal Justice Theories from Asia”—reflects the growing awareness that criminological research on Asian societies is likely to be particularly fruitful for the purposes of modifying established theories precisely because the cultural and institutional contexts of these societies differ from those of Western societies in a number of fundamental respects.1 These differences raise the possibility that theories originating in the West might not exhaust the range of variables, social forms, and processes that are relevant to crime. To the extent that this is the case, understanding crime within Asian contexts is not likely to be accomplished by means of the simple transportation of Western theory; rather, it will require transformation of theory.

The purpose of this paper is to illustrate the ways in which established criminological theories born and nurtured in the West might need to be transformed to be applicable to the context of Asian societies, and more specifically to the societies of East Asia.2 My analyses will focus on two influential theoretical perspectives—Situational Action Theory and Institutional Anomie Theory—that are located at opposite ends of the continuum with respect to levels of analysis. Situational Action Theory is a micro-level theory that directs attention to individuals in their immediate social settings. Institutional Anomie Theory, in contrast, is a distinctively macro-level theory, with a focus on the basic cultural and institutional features of societies.3 My overarching thesis is that the application of each of these theoretical perspectives, as they are currently formulated, to societies in East Asia is problematic because certain concepts do not fit well, or concepts that are needed to understand crime-related phenomena are missing entirely.

Micro-dynamics: Transforming Situational Action Theory

Synopsis of the Theory

Consider first Situational Action Theory (hereafter SAT), a perspective developed and advanced by Per-Olof Wikström and colleagues. The main objective that underlies the formulation of this theory is quite bold and directly relevant to the purposes at hand. Wikström (2011:63) proclaims that “SAT proposes to explain all kinds of crime, in all places, at all times.”4 SAT is thus explicitly intended to provide an explanation of crime with universal applicability, thereby contributing to “theoretical science” as described by Tittle.

The key to realizing this objective is to formulate and incorporate a theory of action that is capable of isolating the operative causal mechanism that produces crime (Wikström et al. 2012, p. 8). According to SAT, crime causation ultimately entails a “perception-choice process” that is grounded in situational dynamics. Depending on their personal characteristics and features of the environments in which they find themselves, actors perceive different alternatives for action and make choices among them. The personal characteristics that are most relevant to crime causation are subsumed under the concept of “criminal propensity.” Criminal propensity depends on the person's set of moral beliefs (the “moral filter”) and his or her ability to exercise self-control. The salient feature of the environment in the explanation of crime is exposure to criminogenic settings. A setting is defined as “... the part of the environment ... that, at any given moment in time, is accessible to a person through his or her senses ...” (Wikström et al. 2012, p. 15). A setting is criminogenic to the extent that its features encourage or fail to discourage law violation.

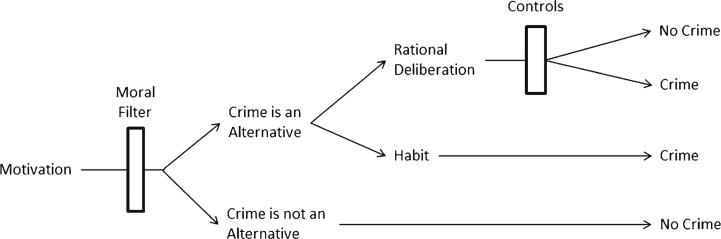

The core components of the perception-choice process are depicted schematically in Fig. 1 (adapted from Wikström et al. 2012, p. 29). Motivations for potential law-breaking serve as the basic inputs to the process.5 The person's set of moral beliefs determines which of these motivations activate an awareness of possible courses of action in his or her consciousness. Only those motivations that pass through the moral filter and activate a criminal “action alternative” have the potential to eventuate in crime. If a potential crime is not perceived as an action alternative, the corresponding crime will not occur. Among the emergent criminal action alternatives, some will be subject to rational deliberation. It is at this point that self-control comes into play. The capacity to make rational assessments of the costs and benefits of engaging in the criminal behavior, given features of the setting, will determine whether the actor actually commits the crime or inhibits a criminal response. The analytic model acknowledges that crime can also come about without appreciable rational deliberation in the form of habitual behavior.

Fig. 1.

The perception-choice process in situational action theory

A commendable feature of SAT is that it integrates many insights about the decision-making processes underlying criminal acts associated with a variety of criminological perspectives. It goes beyond both person-oriented and environment-oriented theoretical approaches by emphasizing that crime is an outcome of an interaction between certain kinds of people in certain kinds of settings. It awards a central role to the concept of morality, a concept which has been curiously absent in much criminological discourse (see Messner 2012, p. 7). Moreover, the theory has the virtue of parsimony. Its central claim can be stated quite succinctly: crime occurs when someone considers a criminal act as a possible behavioral option and chooses to exercise this option given an assessment of the incentives and disincentives at hand.

Despite these commendable features, a major limitation of the theory as currently formulated is that it devotes scant attention to the role of the larger cultural and institutional context. As noted above, the feature of the environment that is awarded causal significance is the immediate setting. Cultural and institutional factors are considered to have some relevance to the understanding of crime causation in SAT, but only by operating as “causes of the causes” in explicit contrast with the “causes” of crime (Wikström 2010, p. 216; 2011, pp. 67–68).

SAT thus depicts the perception-choice process as a causal mechanism that can be analytically extracted from the sociocultural context, with features of that context serving simply as “inputs” to the mechanism. This approach to theorizing implicitly adopts the “universalistic” position with respect to human psychology. As explained by Norenzayan et al. (2007, p. 569), the universalistic position is predicated on the “cardinal assumption that basic cognitive processes are the same for all normal adult human beings, whether in the plains of Central Asia, the villages of East Africa, or the urban centers of Europe and North America.” The content of people's minds differs appreciably across sociocultural settings; people in different parts of the world obviously exhibit a wide range of beliefs and ideas. However, the fundamental “cognitive architecture” of the mind is assumed to be the same everywhere (2007, p. 570).

In an analogous fashion, SAT depicts the perception-choice process as a causal mechanism that operates in essentially the same manner irrespective of the sociocultural context; apparently, it is a psychological universal. Contemporary theory and empirical research in cultural psychology have posed significant challenges to such a universalistic position. Moreover, I suggest that some of the findings from this literature imply that the perception-choice process at the core of SAT will have to be more systematically embedded in cultural and institutional context for it to be able to explain crime in Asian societies.

Bringing in the Sociocultural Context

A good deal of research in cross-cultural psychology over recent decades has documented significant differences in cognition and perception, with much of the research based on comparisons between East Asia and the West. Two particularly important forms of cognition have been differentiated: analytic and holistic (Varnum et al. 2010). Each form is characterized by the foci of attention and by processes of categorization, attribution, and basic reasoning. The unifying element of the analytic style “... is a tendency to focus on a single dimension or aspect ... and a tendency to disentangle phenomena from the contexts in which they are embedded—for example focusing on the individual as a causal agent or attending to focal objects in visual scenes.” The unifying element of the holistic style “... is a broad attention to context and relationships in visual attention, categorizing objects, and explaining social behavior” (Varnum et al. 2010, p. 9).

These respective forms of cognition tend to “link up” with differences in social orientations that reflect the larger sociocultural context. The key distinction is that between an “independent” social orientation and an “interdependent” social orientation. “Cultures that endorse and afford independent social orientation tend to emphasize self-direction, autonomy, and self-expression. Cultures that endorse and afford interdependent social orientation tend to emphasize harmony, relatedness, and connection” (Varnum et al. 2010, p. 9).

One of the more significant “domains” according to which social orientations differ is that of the “self” and the associated styles of action (Kitayama et al. 2007; see also Kitayama and Uchida 2005). Although the “self” is evidently a human universal, it can be constructed or construed in two distinctive ways: as an “independent self” or an “interdependent self.” The independent self entails a personal social identify that is sharply bounded, whereas the interdependent self is characterized by a relational social identity, as something that intrinsically overlaps with close others (Varnum et al. 2010, p. 10).

The accumulated body of evidence documenting cross-cultural variation in social orientation and cognitive style implies that, at the very least, the role of the sociocultural context for understanding of the perception-choice process associated with crime causation is under-theorized in SAT. Recall that SAT emphasizes that crime results from the interaction of person and environment, with the relevant feature of the environment being that of “settings.” Moreover, Wikström and colleagues recognize that it is ultimately the perceptions of the environment that influence social action. They further acknowledge that “understanding why people vary in the action alternatives that they perceive in a particular setting is central to the explanation of why they follow or break rules of conduct” (Wikström et al. 2012, p. 18).

The cross-cultural evidence reveals that there are pronounced differences in basic perceptual processes associated with cognition, particularly between East Asians and Westerners. The holistic mode of cognition is prevalent in East Asian societies, whereas the analytic mode of cognition is prevalent in Western societies (Nisbett 2007; Norenzayan et al. 2007). As a result, East Asians and Westerners literally see the same environment differently. It follows that any successful application of SAT to East Asian societies will require that the operative perceptual processes associated with that sociocultural context be systematically incorporated into the causal explanation. Otherwise, the theorist will be unable to comprehend the social construction of the settings within which the perception-choice process unfolds.

The research that has emerged in cross-cultural psychology similarly calls attention to the pressing need to contextualize theorizing about the “moral filter.” As noted above (see also Messner 2012), SAT assigns a prominent role to morality for understanding the decision-making process that underlies crime causation. The theory stipulates that: “When a person's morality is sufficiently strong, it can prevent a particular breach of the law from entering his or her consciousness. The associated criminal act is literally ‘unthinkable’” (Messner 2012, p. 8). The moral filter thus serves as “the first line of defense” in inhibiting crime “by effectively restricting the range of situations to which the decision-making processes that are well explicated in other criminological perspectives will be applied” (Messner 2012, p. 9).

Once again, however, the evidence indicates that the relevant cognitive processes—in this instance those of moral reasoning itself—are not universal (Markus and Hamedani 2007; Heine and Norenzayan 2006). For example, researchers have distinguished between “duty-based” moral beliefs and “rights-based” moral beliefs (Chiu et al. 1997). For the former, “duty is the fundamental justification for the moral rightness of human action,” whereas for the later “human rights [as understood within the culture] are the fundamental justification for the moral rightness of human action” (1997, p. 923). These moral belief systems tend to be grounded in differing implicit theories of the person. Evidence indicates that moral attributions in East Asian societies are more likely to be guided by duty-based moral beliefs. Those in Western societies are more likely to be guided by rights-based moral beliefs (An and Trafimov 2014; Chiu et al. 1997). Given these differences, it seems highly likely that the processes of moral filtering associated with crime causation will differ in fundamental ways between East Asian and Western contexts.

The cross-cultural evidence pertaining to independent vs. interdependent self-construals further suggests that SAT lacks some of the pieces of the puzzle of crime. These respective self-construals entail distinctive styles of action and principles of regulation.6 The independent mode of self-construal is associated with “action as influence” and with self-centricity, whereas the interdependent self is characterized by “action as adjustment” and with other-centricity. With respect to principles of regulation, goal-directedness is prominent for the independent self. The corresponding principle for the interdependent self-construal is responsiveness to social contingencies. A fairly large body of evidence has accumulated indicating that these “modes of being” differ markedly between East Asian populations and Western (especially North American) populations. The independent mode is more prevalent in the West and the interdependent mode in East Asia.

These findings once again highlight the need for more systematic theorizing about the role of the sociocultural context for understanding the perception-choice process as it unfolds in East Asian societies. Given the varying ways in which the self can be construed and the associated forms of agency, it seems highly likely that the very nature of self-control will vary across societal contexts. This suggests that new conceptual tools will be needed to capture the internal controls that are operative in East Asia, such as the conceptualization of forms of self-control that are relevant to the interdependent self (see Messner 2014).

To summarize these arguments at a more general level, the accumulated body of evidence that has documented pronounced cross-cultural variation in social orientations and cognitive styles implies that the “bracketing” of features of the sociocultural context as mere “inputs” into the mechanism of crime causation is likely to be unsatisfactory if SAT is to offer an adequate explanation of crime in East Asia. Rather, the insights from cultural psychology imply that SAT needs to be transformed in significant ways to accommodate the reality that the nature of psychological processes, including the perception-choice process, is culture-bound.7

Macro-dynamics: Transforming Institutional Anomie Theory

Synopsis of the Theory

In contrast with SAT, Institutional Anomie Theory (hereafter IAT) assigns primary importance to the sociocultural context for understanding the causes of crime. The theory focuses directly and explicitly on the properties of large-scale social systems such as societies—their fundamental cultural orientations, institutional structures, and institutional norms. Nevertheless, upon careful consideration, key arguments of IAT, similar to SAT, exhibit a culturally tinged logic that raises questions about its applicability to East Asian societies.

To summarize briefly, IAT seeks to identify the forms of social organization at the societal level that are conducive to anomie and ultimately to crime.8 The theory assumes that some degree of integration among the major social institutions is required for society to function, but that the accomplishment of such integration is necessarily problematic. The requirements for the effective functioning of any given institution may conflict with the requirements of another. One such conflict involves competing demands associated with role performance. Given the fact that time is a finite resource, performing a given institutional role may preclude performing another role. In addition, the kinds of orientations towards social interactions that are appropriate often differ depending on the institutional domain (e.g., interactions in the marketplace versus those in the family). Actors in concrete societies are accordingly required to make trade-offs among role demands and to shift their basic orientations as they negotiate the different institutional domains.

Any given society will therefore be characterized by a distinctive arrangement of social institutions that reflects a balancing of the sometimes competing claims and requisites of these institutions, yielding a corresponding “institutional balance of power.” The central claim of IAT is that the type of institutional configuration that is conducive to high levels of crime in contemporary societies is one in which the roles and the associated logics of the economy are awarded highest priority. In such a society, the economy tends to dominate the institutional structure in the following ways. Non-economic institutional roles tend to be devalued relative to economic roles. Individuals feel pressures to accommodate other roles to economic roles when conflicts emerge. Finally, the logic of the marketplace intrudes or penetrates into other realms of social life (Messner and Rosenfeld 2007, pp. 82–83).

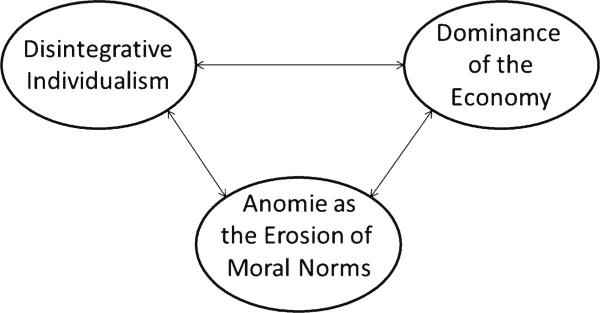

Economic dominance in the institutional order, in turn, is theorized to be grounded in an extreme form of individualism that is inherently disintegrative. This extreme or disintegrative individualism encourages the “ruthless pursuit of one's own interests while treating others as mere ‘means’ in strategic interactions” (Messner et al. 2008b, p. 172). Furthermore, economic dominance in the institutional order is conducive to anomie. Under conditions of pervasive anomie, the moral authority of the social norms begins to erode, and action tends to be guided primarily by considerations of pure technical expediency. IAT thus depicts the macro-level dynamics of crime causation with reference to the constellation of the cultural, institutional, and normative features of a society as shown in Fig. 2. The type of social organization that is hypothesized to be highly criminogenic is one in which cultural values coalesce around disintegrative individualism; the economy is dominant; and anomie is manifested as the erosion of the moral authority of the institutional norms.

Fig. 2.

The IAT analytic model of criminogenic social organization

An attractive feature of IAT is its comprehensive analytic framework. The principal components of macro-social organization are included: a society's dominant cultural values, its institutional arrangements, and its institutional norms. In addition, IAT incorporates key insights from classical social thought about the challenges associated with the transition from traditional, pre-modern societies to highly complex societies. Most prominently, IAT builds upon Durkheim's (1964/1893) analyses of the central role played by “moral individualism” as the source of social solidarity in the advanced societies (Giddens 1971, pp. 95–104; see also Emirbayer 2003).9 This type of value orientation regards the individual as “the carrier of universal rights and obligations.” It is “based on mutual sympathy and respect for others” (Messner et al. 2008b, p. 171), and as such it fosters social bonds among the differentiated members of society. Excessive or disintegrative individualism, as conceptualized in IAT, essentially represents an aberrant or a degraded variant of the value complex that is expected to serve as the “social cement” in the advanced societies.10

Ironically, the secure grounding of IAT in the traditions of classical Western social thought proves to be something of an Achilles heel when it comes to the application of the theory to East Asian societies. The intellectual problematic that underlies the perspective is the inherent tension between social solidarity and individualistic cultural values. Yet, as alluded to above and as noted widely in the literature, a pronounced cultural difference between East Asian and Western societies is the relative emphasis on collectivism vs. individualism.11 Nisbett contrasts the Western individualistic orientation with the East Asian collectivistic orientation in the following terms:

Insistence on freedom of individual action vs. a preference for collective action.

Desire for individual distinctiveness vs. a preference for blending harmoniously with the group.

A preference for egalitarianism and achieved status vs. acceptance of hierarchy and ascribed status.

A belief that the rules governing proper behavior should be universal vs. a preference for particularistic approaches that take into account the context and the nature of the relationships involved. (Quoted from Nisbett 2003, pp. 61–62).

In view of these salient cross-cultural differences, a fundamental question arises. To what extent can a theoretical perspective on crime that has been formulated with reference to the inherent tension between social solidarity and individualistic cultural values be applied to societies that are characterized by collectivistic cultural values? I suggest that the abstract analytic framework embodied in IAT has general applicability, but the content of the theoretical argument needs to be recast to capture the distinct features of the differing sociocultural contexts.

At present, I can offer only some tentative and highly speculative ideas about the kinds of elaborations of IAT that would render the theory more applicable to the macro-dynamics of crime in East Asian societies. These ideas have been stimulated to a large extent by the research on corruption in contemporary China. Corruption has become a major concern among Chinese governmental officials, academics, and the general public, with various data sources indicating increasing prevalence of offending and rising costs to the society (see, for example, Messner et al. 2008a). Moreover, China scholars have proposed that this particularly troubling form of offending is related to a distinctive feature of Chinese society—the phenomenon of “guanxi.” The concept of guanxi is a somewhat slippery one, but it is generally understood to refer to networks of social relations that involve aspects of interpersonal bonding, reciprocity, and mutual trust (Geddie et al. 2005; see also Gold et al. 2002).

A recent study by Ling Li (2011) offers an insightful explanation of the corruption/guanxi nexus that can serve as a springboard for an elaboration of IAT.12 Li (2011, p. 4) analyses the specific offense of bribery, observing that bribery “has become the most common as well as damaging type of corruption in China in recent years.”13 Li argues that the potential participants in acts of bribery must be able to surmount significant barriers before they will be willing to engage in these acts. One such barrier entails the contemplation of the risk of legal sanctioning (referred to as “external exchange safety”). The growing awareness of bribery in China has led to intensified and well-publicized anti-corruption campaigns by the government. Although the probabilities of detection and punishment are still relatively low, the legal punishments that can be imposed upon conviction are quite severe. A second barrier is that of “internal exchange safety.” This refers to the risk that one of the participants will behave opportunistically and fail to “deliver the goods.” Opportunistic behavior can of course be a risk in many transactions, but it is particularly problematic in corrupt activities because “the loss resulting from non-performance cannot be redressed through legal institutions because of the illegality of the exchange” (Li 2011, p. 15). A final barrier is that of the moral costs of bribery. Given the public condemnation of bribery and acts of corruption more generally, participants in these acts must be able to deal with any cognitive dissonance that arises from a disparity between one's actions and the prevailing moral sentiments.

Li (2011, p. 1) proposes that acts of bribery in China unfold in accordance with rules of conduct and etiquettes that reflect the guanxi-practice more generally. This practice entails the offering and acceptance of gifts by potential bribers, which recipients reciprocate, and which evolve into repeated exchanges of favors. These features of guanxi-practice ultimately help remove the aforementioned barriers to bribery. The time lapse between gift-giving and favor-seeking blurs the causal connection between the two, reducing the risk of legal sanctioning. The offering of gifts as initial payment and the reciprocating of favors demonstrate the commitment on the part of participants, removing the barrier of internal exchange safety. Finally, the entire sequence of interactions is situated within a culturally acceptable context—guanxi. This effectively neutralizes moral inhibitions and rationalizes the transactions. Guanxi-practice thus serves as an “operating mechanism” that facilitates bribery by removing the barriers to these illegal transactions (Li 2011, p. 20).

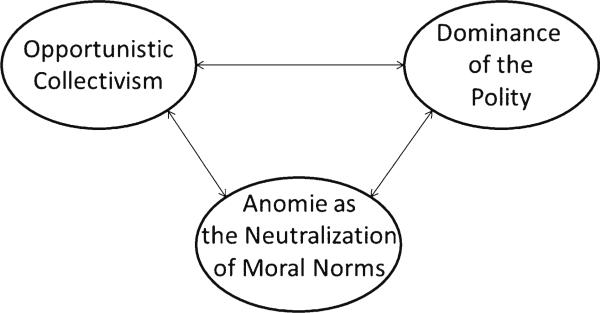

Li's account of the social reality of bribery as a form of corruption in China is not easily interpreted through the lens of Institutional Anomie Theory. The salient processes do not appear to be grounded primarily in some aberrant or degraded form of individualism. To the contrary, the envelopment of bribery within the cultural practices of guanxi underscores the centrality of collectivistic values within the social context. These values, however, do not serve to integrate the participants into the societal community. They ultimately facilitate crime. Rather, I suggest that the value orientation facilitating bribery reflects an aberrant or degraded form of the dominant values that are commonly found in East Asia. This value orientation might be conceptualized as “opportunistic collectivism.” Referring back to the analytic framework of IAT, opportunistic collectivism can be viewed as an analogue for East Asian societies of disintegrative individualism for Western societies.

How might this criminogenic form of cultural values “link up” with the institutional structure? The Chinese case suggests that the type of institutional configuration aligned with opportunistic collectivism might be that of dominance of the polity rather than dominance of the economy (see Messner and Rosenfeld 2001). The polity is the social institution that is oriented toward the collective mobilization of the population. Although China has opened up markets in the course of its economic reform, the state remains a powerful institutional actor in the system.14 Moreover, research indicates that the selective introduction of market reforms under the direction of a supervening governmental apparatus has generated distinctive “institutional incompatibilities” in China that create strong incentives and opportunities for bribery and other forms of corruption (Messner et al. 2008a; see also Gong 2002).

Li's research further suggests a possible reconceptualization of the remaining element in the analytic framework of IAT—the vitality of the normative order. As noted above, IAT directs attention to the criminogenic implications of “anomie,” understood in terms of the erosion of the moral authority of the social norms. The norms become largely irrelevant because actors are guided primarily by considerations of technical expediency. In Li's analysis of bribery, the “freedom to offend” comes about not so much because moral norms have eroded but because they can be effectively neutralized. Accordingly, the form of anomie that might be likely to arise in social systems characterized by opportunistic collectivism and dominance of the polity is one in which the institutional norms are readily and commonly neutralized. Research in the USA by Yu (2013) on attitudes toward digital piracy is highly consistent with this interpretation. Yu reports that Asian college students studying in the USA are significantly more likely to invoke “techniques of neutralization” to justify digital piracy than are their American counterparts, even though the two groups do not differ with respect to indicators of “general morality.”

These theoretical arguments deriving from the case of corruption in China can be represented in a companion IAT analytic model, which is depicted in Fig. 3. As in the current formulation of IAT, the macro-dynamics of crime are explained with reference to the core features of social organization—pervasive cultural values, the balance among social institutions, and the vitality of the normative order. The content is nevertheless quite different, highlighting opportunistic collectivism, political dominance, and neutralized moral norms. It is important to emphasize that this model is intended as an ideal-typical form of social organization. Although the model has been inspired by criminological research on contemporary China, the extent to which China or any other society conforms to its features is an open, empirical question.

Fig. 3.

An IAT analytic model of criminogenic social organization in collectivistic societies

Summary and Conclusion

I have argued that the accumulated evidence from cross-cultural psychology and criminological research in East Asian societies raises serious questions about the feasibility of simply transporting two criminological perspectives—SAT and IAT—from the West to the East. Upon careful examination, it becomes clear that both of these theories have incorporated the underlying logics and ways of thinking that are prevalent in the West. This is not surprising; both theories were formulated by Western criminologists who principally drew upon the knowledge base of Western criminological research and Western social thought. As a result, the basic concepts of each theory are “... saturated with culturally specific meanings,” to borrow a phrase from Marenin and Reisig.15 My analysis suggests that the formulation of theoretical explanations of crime that are truly universal will require criminologists to create and incorporate new concepts that are more faithful to the social realities of non-Western societies, societies such as those in East Asia and Asia more generally.

I have also offered some preliminary reflections about how the two theories under investigation might be transformed to enhance their fit to East Asian contexts. These remarks are admittedly sketchy, and they raise more questions than they answer. With respect to micro-dynamics of SAT, how does the adoption of a holistic or an analytic mode of cognition affect perceptions of a given setting as more or less criminogenic? Does the application of rights-based principles of moral attribution “filter” motivations into criminal action alternatives differently than the application of duty-based principles of moral attributions? To what extent and in what ways do the respective forms of self-construal—independent and interdependent—condition the processes of self-control?

With respect to macro-dynamics of IAT, how can the basic concepts in the abstract analytic model be operationalized? Assuming that such operationalization is feasible, how well does the ideal-typical model of social organization proposed as an analogue for the model that has been applied in the West actually describe societies in East Asia? Is the proposed form of social organization criminogenic, i.e., is it associated with particularly high levels of crime that take the theoretically expected forms?

Addressing these kinds of questions is admittedly a tall order; theoretical transformation is not for the faint of heart. Nevertheless, it seems highly likely that criminological research on Asian societies, particularly by criminologists who are able to view the world through the lenses of Asian cultures, will play an indispensable role in both raising and answering them. In so doing, such research can move the field forward as we strive to realize the laudable goal of developing truly general theories, theories that prove to have universal applicability.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented as a keynote address at the 6th Annual Conference of the Asian Criminological Society, Osaka, Japan, June 27–29, 2014.

The utility of comparing Asian and Western societies to develop criminological theory given the pronounced institutional and cultural differences has been widely recognized. See, for example, Aranha and Burress (2010), Chen (2004), Cheung and Cheung (2008), Kobayashi et al. (2010), Liu (2011), Messner (2014), and Yun and Walsh (2011).

The research in cross-cultural psychology reviewed below focuses primarily on contrasts between the West and the East Asian societies of China, Japan, and Korea. See, for example, Nisbett (2003, 2007), Norenzayan et al. (2007), and Varnum et al. (2010). Oyserman et al. (2002) highlight some of the important cultural differences within Asian and East Asian societies.

I have argued elsewhere (Messner 2012) that despite their focus at different ends of the continuum with respect to levels of analysis, Situational Action Theory and Institutional Anomie Theory are promising candidates for theoretical integration because morality plays a central role in both.

This passage echoes similarly bold claims by Gottredson (2006, p. 83) that the “general theory of crime” (commonly referred to as self-control theory) has universal applicability. See also Gottfredson and Hirschi (1990).

Two general types of motivations are differentiated in SAT: temptations and provocations. See Wikström (2010).

The following discussion draws upon Kitayama et al. (2007). See also Markus and Hamedani (2007).

See Barbalet (2011) for an insightful analysis of how “agency” and “action,” which are at the core of SAT, have been understood very differently in traditional Chinese thought in comparison with Western thought.

The following synopsis of IAT is adapted from Messner (2012). See also Messner and Rosenfeld (2006, 2007) and Messner et al. (2008b).

In addition to drawing upon Durkheimain social thought, IAT is informed by Polanyi's (1957/1944) observations about the socially destructive tendencies of the “self-regulating market.” See Messner and Rosenfeld (2000).

See Karstedt (2006) for empirical evidence indicating that individualistic and egalitarian values are associated with lower levels of level violence.

Nisbett (2003, 2007) offers comprehensive summaries of the literature on cross-cultural differences in individualism and collectivism, and he proposes that these differences can be interpreted with reference to features of the ecological organization of societies. See Hofstede (2001) for an extended discussion of cross-national differences in basic cultural values more generally.

See Tam (2011) for an analysis of “organizational corruption” in the hospital sector of contemporary China.

Li's analyses are based on four principal data sources: interviews about corrupt practices, court documents and press releases about cases involving bribery, diaries and essays about experiences with bribery, and a quasi-autobiography of a person convicted for bribing judges.

Researchers in political economy have long noted the prominent role of governmental agencies in promoting economic growth in Asian nations, which has been referred to as the “Asian developmental state.” See Chu (2009) for a critique of recent claims that the Asian developmental state (specifically in South Korea) is ill-equipped to deal with the emergence of the globalized knowledge economy.

On the basis of their examination of crime in Nigeria, Marenin and Reisig (1995, p. 502) challenge Gottfredson and Hirschi's (1990) claim that self-control theory is a universal theory, arguing in part that “the basic concepts employed in the theory—force, fraud, opportunities, social consensus, deviance, prudence, self-control—are saturated with culturally specific meanings.”

References

- An S, Trafimov D. Affect and morality: a cross-cultural examination of moral attribution. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2014;45:417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Aranha MF, Burruss GW. An exploratory study of the variation in Japan's embezzlement rates via institutional anomie theory. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice. 2010;34:281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Barbalet J. Market relations as Wuwei: Daoist concepts in analysis of China's post-1978 market economy. Asian Studies Review. 2011;35:335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett RR. Constructing cross-cultural theories in criminology. Criminology. 1980;18:252–268. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Social and legal control in China: a comparative perspective. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2004;48:523–536. doi: 10.1177/0306624X04265225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung NWT, Cheung YW. Self-control, social factors, and delinquency: a test of the general theory of crime among adolescents in Hong Kong. Journal of Youth Adolescence. 2008;37:412–430. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C.-y., Dweck CS, Tong J. Y.-y., Jeanne Ho-ying FU. Implicit theories and conceptions of morality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:923–940. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y.-w. Eclipsed or reconfigured? South Korea's developmental state and challenges of the global knowledge economy. Economy and Society. 2009;38:278–303. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. The division of labor in society. Free Press; New York: 1964. 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Emirbayer M. Introduction: Emile Durkheim: sociologist of modernity. In: Mustafa E, editor. Emile Durkheim: sociologist of modernity. Blackwell; Malden: 2003. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Geddie MW, DeFranco AL, Geddie M. A comparison of relationship marketing and guanxi: its implications for the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2005;17:614–632. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. Capitalism and social modern social theory: an analysis of the writings of Marx, Durkheim, and Weber. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Gold T, Doug G, David W. Introduction. In: Thomas G, Doug G, David W, editors. Social connections in China: institutions, culture, and the changing nature of guanxi. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gong T. Dangerous collusion: corruption as a collective venture in China. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 2002;35:85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR. The empirical status of control theory in criminology. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR, editors. Taking stock: the status of criminological theory, advances in criminological theory. Vol. 15. Transaction Publishers; New Brunswick: 2006. pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson MR, Hirschi T. A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press; Stanford: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. Toward a psychological science for a cultural species. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2006;1:251–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Culture's consequences. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Karstedt S. Democracy, values, and violence: paradoxes, tensions, and comparative advantages of liberal inclusion. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2006;605:50–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Yukiko U. Interdependent agency: an alternative system for action. In: Sorrentino RM, Cohen D, Olson JM, Zanna MP, editors. Culture and social behavior: the Ontario symposium. Vol. 10. Lawrence Erlbaum Associate; Mahwah: 2005. pp. 137–164. [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Sean D, Yukiko U. Self as cultural mode of being. In: Shinobu K, Dov C, editors. Handbook of cultural psychology. Guilford; New York: 2007. pp. 136–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi E, Vazsonyi AT, Chen P, Sharp SF. A culturally nuanced test of Gottfredson and Hirschi's “general theory”: dimensionality and generalizability in Japan and the United States. International Criminal Justice Review. 2010;20:112–131. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn ML. Cross-national research as an analytic strategy—American sociological association, 1987 presidential address. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:713–731. [Google Scholar]

- Li L. Performing bribery in China: guanxi-practice, corruption with a human face. Journal of Contemporary China. 2011;20:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liu RX. Strain as a moderator of the relationship between parental attachment and delinquent participation: a China study. International Criminal Justice Review. 2011;21:427–442. [Google Scholar]

- Marenin O, Reisig MD. A general theory of crime’ and patterns of crime in Nigeria: an exploration of methodological assumptions. Journal of Criminal Justice. 1995;23:501–518. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Hamedani MG. Sociocultural psychology: the dynamic interdependence among self systems and social systems. In: Shinobu K, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of cultural psychology. Guilford; New York: 2007. pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF. Morality, markets, and the ASC: 2011 presidential address to the American society of criminology. Criminology. 2012;50:5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF. Social institutions, theory development, and the promise of comparative criminological research. Asian Journal of Criminology. 2014;9:49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Rosenfeld R. Market dominance, crime, and globalization. In: Karstedt S, Bussman K-D, editors. Social dynamics of crime and control: new theories for a world in transition. Hart; Portland: 2000. pp. 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Rosenfeld R. An institutional-anomie theory of crime. In: Paternoster R, Bachman R, editors. Explaining criminals and crime. Roxbury; Los Angeles: 2001. pp. 151–160. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Rosenfeld R. The present and future of institutional anomie theory. In: Cullen FT, Wright JP, Blevins KR, editors. Taking stock: the status of criminological theory (Advances in criminological theory. Vol. 15. Transaction; New Brunswick: 2006. pp. 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Rosenfeld R. Crime and the American dream. 4th ed. Wadsworth; Belmont: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Jianhong L, Karstedt S. Economic reform and crime in contemporary urban China: paradoxes of a planned transition. In: Logan JR, editor. Urban China in transition. Blackwell; Malden: 2008a. pp. 271–293. [Google Scholar]

- Messner SF, Thome H, Rosenfeld R. Institutions, anomie, and violent crime: clarifying and elaborating institutional-anomie theory. International Journal of Conflict and Violence. 2008b;2:163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE. The geography of thought: how Asians and Westerners think differently ... and why. Free; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbett RE. Eastern and Western ways of perceiving the world. In: Yuichi S, Cervone D, Downey G, editors. Persons in context: building a science of the individual. Guilford; New York: 2007. pp. 62–83. [Google Scholar]

- Norenzayan A, Incheol C, Kaiping P. Perception and cognition. In: Shinobu K, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of cultural psychology. Guilford; New York: 2007. pp. 569–594. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, Kemmelmeier M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:3–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanyi K. The great transformation: The political and economic origins of our time. Beacon; Boston: 1957. 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Tam W. Organizational corruption by public hospitals in China. Crime Law and Social Change. 2011;56:265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Tittle Charles R. The uses of, and technology for international surveys.. Presidential Panel at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Criminology; 2013. http://www.asc41.com/Annual_Meeting/2013/Presidential%20Papers/Tittle-PPslides.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Varnum MEW, Grossman I, Kitayama S, Nisbett RE. The origin of cultural differences in cognition: the social orientation hypothesis. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:9–13. doi: 10.1177/0963721409359301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikström P-OH. Explaining crime as moral action. In: Hitlin S, Stephen V, editors. Handbook of the sociology of morality. Springer; Berlin: 2010. pp. 211–239. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström P-OH. Does everything matter? Addressing the problem of causation and explanation in the study of crime. In: McGloin JM, Silverman CJ, Kennedy LW, editors. When crime appears: the role of emergence. Routledge; New York: 2011. pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström P-OH, Oberwittler D, Treiber K, Hardie B. Breaking rules: the social and situational dynamics of young people's urban crime. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yu S. Digital piracy justification: Asian students versus American students. International Criminal Justice Review. 2013;23(2):185–196. [Google Scholar]

- Yun I, Walsh A. The stability of self-control among South Korean adolescents. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2011;55:445–459. doi: 10.1177/0306624X09358072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]